Executive Summary

Historically, one of the benefits of purchasing index mutual funds and ETFs has been the simple transaction cost savings of being able to buy into a diversified portfolio of securities in a single step (pooled) transaction, rather than absorb the transaction costs of buying a small quantity of each individual investment one at a time (not to mention the sheer trading complexity of trying to do so). Yet since fixed trading commissions were deregulated in 1975, transaction costs have faced an ongoing inexorable decline, as competition from discount brokerage firms, then online discount brokers, and more, drive the cost of implementing a trade closer and closer to zero (or at least, to the point of being truly negligible).

Yet at the point that transaction costs really do become negligible, an interesting question arises: why bother to buy index funds or ETFs at all, instead of simply using technology and near-zero trading costs to buy, own, and manage a portfolio of all the underlying individual investments directly. At face value, the investment characteristics may be the same either way, but for tax purposes there is a key distinction: owning each individual investment at such a granular level allows investors to be far more selective about proactively harvesting capital losses (or even gains in certain situations) or taking more tax-sensitive liquidations in retirement (and of course harvesting itself is easier in an environment where there are no trading costs to engage in such strategies in the first place)!

The end result is a kind of "Indexing 2.0" solution, where investors still hold the investments of an index fund, but without actually using a pooled index mutual fund or ETF itself, opting instead to own the underlying individual investment directly and take advantage of the associated tax benefits. And the concept isn't entirely new; in fact, Wealthfront offers a version of this exact service to replace the S&P 500 with the underlying investments against which proactive capital loss harvesting can be done on a daily basis. While this "Wealthfront 500" service still has a $500,000 minimum, it seems only a matter of time before ever-declining transaction costs make this feasible at a lower and lower price point... until eventually, there may still be value to indexing itself, but there will be little reason for index mutual funds and ETFs at all?

Mutual Funds And Managing Transaction Costs

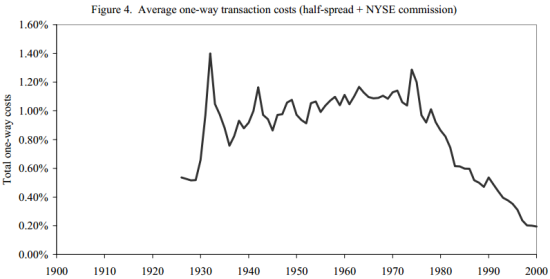

Although we often think of it as a means to access professional investment management, early on the mutual fund really served two key functions: to bring professional investment managers to retail investors, and to allow for economies of scale in trading and investing. In a world where individual stock trades could cost 1%-2% per trade or more - each way! - being able to pool investments, avoid small odd lot trades for modest investments, and command institutional pricing on the purchase of securities was no small feat.

In fact, in recent decades this benefit of transaction costs alone has commanded a tremendous investment in mutual funds. Witness the rise of Vanguard, now pushing beyond 2 trillion in assets under management, for which almost all of the funds are indexed; Vanguard’s appeal is not accessing professional active managers, but is simply the incredibly low pricing to access a broad slice of diversified investments, reflecting the incredible economies of scale available to mutual (and exchange-traded) funds, relative to what the trading costs would be to buy small slices of each of those securities one-at-a-time for an individual portfolio.

However, for the past several decades there has been a powerful countervailing force – the massive decline in transaction trading costs since the brokerage commission rate was deregulated in 1975. While the change in rules reduced costs for institutional traders as well (and may have even helped to spawn the growth of index funds), the end of industry-fixed trading commissions on "May Day" (the rule took effect on May 1, 1975) led to the rise of discount brokerage platforms for consumers, which was accelerated further with the rise of online discount brokerage platforms about 20 years later. Once price competition could function, the cost for transactions began to fall from their 1975 peak, and the decline has continued ever since, as shown in the chart below from research by Charles Jones (notably, the chart ends in the early 2000s when Jones published his research, but the downward cost trend has continued).

But imagine, for a moment, that the chart above showing declining transaction costs continues to wind towards its inexorable future – where transaction costs approach zero (or at least, become truly "negligible") for retail investors. What is the function of a mutual fund – or especially an ETF or index fund – when the underlying individual investments can be purchased directly with negligible transaction costs anyway?

How Indexing Changes When Transaction Costs Are Negligible

Imagine for a moment that we’ve fast forwarded to that future, and transaction costs are now either zero or so close to that point they’re “negligible” to even the investor with just a modest portfolio. What is the purpose of holding an ETF or index fund at that point? There is certainly a benefit of simple access to diversification – we own the S&P 500 index fund because it’s an easy and convenient way to own an allocation of 500 stocks in a single simple purchase transaction, rather than going through the hassle of 500 stock purchases (which may be time-consuming, even if the transaction costs are negligible).

But now imagine a second innovation in this era of negligible transaction costs: portfolio management software that can instantly purchase all the stocks in the S&P 500 with the single click of a button, just like owning the S&P 500. Except you don’t actually own the S&P 500 as an index fund. Your portfolio will actually show individual positions in each of the 500 stocks in the S&P 500, in the correct amounts… which is feasible, because a computer can easily track the stocks and determine the appropriate share amounts to mimic the index, and with negligible transaction costs they really can be purchased, one at a time. Call it Indexing 2.0.

Of course, just because you can use a computer and low transaction costs to help you own the 500 stocks of the S&P 500 individually, instead of as a mutual fund or ETF, doesn’t mean you should. So why would you want Indexing 2.0 over the existing 1.0 version? In a word: taxes.

The Tax Benefits Of NOT Using Mutual Funds And ETFs

One of the fundamental challenges of investing using mutual funds and ETFs is that if some of the underlying investments are down, while others are up, the investor who wants to engage in proactive tax planning is stuck. An investor in the S&P 500 can only harvest losses based on the NAV of the mutual fund (or the market price of the ETF) based on the aggregate position, not by looking through to its component parts and trading those instead.

By contrast, with the Indexing 2.0 solution, the investor really can engage in tax planning at a more granular investment-by-investment level. If there are 27 stocks in the S&P 500 that are down those week, those 27 can be harvested for losses, leaving the remaining 473 intact, in a manner that simply cannot be achieved with a traditional indexing solution (as if the single index fund is up in the aggregate, there's nothing to harvest at the index fund level). And of course, the technology can monitor the portfolio on a continuous basis, ensuring that the desired losses are harvested one stock at a time opportunistically on any day of the year in which the opportunity presents itself! Similarly, retirees who are taking distributions from a portfolio can liquidate in a far more tax-sensitive manner when share lots at the individual stock level can be "cherry picked" to maximize favorable tax consequences (e.g., by picking the higher-cost-basis individual shares to reduce potential capital gains exposure).

Another benefit of the Indexing 2.0 solution is that it avoids the potential complication of funds with embedded gains distributions that are triggered by net outflows from the fund (e.g., during severe market turmoil). If a mutual fund has a lot of gains and departing investors force too many sales, the fund can potentially be forced to accelerate the pass-through of gains for the remaining shareholders that are triggered by the ones who left. And an investor who buys an existing fund that has appreciated may buy into the embedded gains of the prior shareholders. With an Indexing 2.0 solution, the investor directly holds their own investments, avoiding any of these complications.

And of course, it’s worth noting that for investors in lower tax brackets, the ideal is actually not to harvest losses, but to harvest gains instead and take advantage of those low rates (especially those eligible for the 0% capital gains tax bracket). Here, too, the Indexing 2.0 solution allows for a more granular implementation, harvesting the exact amount of gains across various individual stocks that might not have been possible with the fund in the aggregate. In fact, two investors with the same Indexing 2.0 solution could go opposite directions – one harvesting losses, and the other harvesting gains – and each can implement based on their individual preferences and tax situation, in a manner that wouldn’t be possible with a fund (i.e., if the fund is up in total there are no losses to harvest, and if the fund is down there are no gains to harvest, but an Indexing 2.0 solution allows investors to find gains or losses as they wish at the individual stock level, even if they would net out across the fund in the aggregate).

A Glimpse Of Indexing 2.0 – Robo-Indexing With Rebalancing Software And Robo-Advisors

While this Indexing 2.0 concept might sound fantastical to some, the reality is that it already exists and is being implemented in certain forms.

For instance, leading financial advisors have been using “rebalancing software” platforms for nearly a decade, which allows them to build model portfolios and then monitor those portfolios continuously, not only to take advantage of opportunistic rebalancing but also any tax loss (or gains) harvesting opportunities that may present themselves. Although not typically done at the individual stock level – for advisors, these strategies are more commonly implemented with mutual funds and ETFs – there’s little practical constraint to expanding it to the individual stock level, too, beyond the sheer trading costs from custodians of trying to transact in so many stocks (a cost which, again, is falling inexorably lower with every passing year). With transaction costs low enough, there's no reason why rebalancing software couldn't manage models designed at the individual security level, rather than at the fund level.

An even more direct application of the Indexing 2.0 solution is from “robo-advisor” automated investment service Wealthfront, as their Wealthfront 500 offering does this exactly: in lieu of holding the S&P 500, the WF500 invests clients into the underlying individual 500 stocks of the index, using Wealthfront's technology and low trading fee arrangements to make the service feasible to implement for a very modest ongoing AUM fee. And while the value of capital loss harvesting is sometimes overstated, nonetheless Wealthfront has supported with their own research that there is indeed additional tax value to be had by being able to harvest capital losses more granularly at the individual stock level than being forced to rely on a single S&P 500 index fund.

While the Wealthfront 500 may be designed specifically to replicate just a particular index position - the S&P 500 - an expansion of software tools (for advisors or consumers directly) could easily allow for a wider range of indexing choices. Click one button to add the S&P 500 to your portfolio. Click another to add the Russell 2000. Yet another to give your stock weightings an overweight to your preferred sector. And one more to give all the weightings a DFA-style small and value tilt. Again, in the end the portfolio itself might own the exact same underlying securities that would have been owned by simply buying the S&P 500 index, the Russell 2000 index, a sector fund, or some DFA funds... just without the actual funds, allowing for a more granular level of ownership that provides the potential for a more refined level of tax loss harvesting (not to mention a potential cost savings on fund fees).

Direct Indexing 2.0 – Coming Soon(ish)?

At this point, we may merely be on the cusp of Indexing 2.0. As noted earlier, advisory firms theoretically could do this with their rebalancing software tools, but it might be a bit ‘complex’ with so many investment positions until the tools improve (to handle model portfolios with a larger quantity of positions and more 'templates' for models to mimic the underlying indices), and transaction costs on traditional custodial platforms would still be prohibitive for any but the most affluent of clientele to proceed at this point. Even Wealthfront’s technology and trading arrangements, built to accommodate their Wealthfront 500 solution, still currently have a $500,000 minimum (though ostensibly, the larger the platform gets, the more it may be able to negotiate its costs and therefore its minimums lower).

Nonetheless, it’s not difficult to look at the steady inexorable progression of transaction costs getting lower and lower to recognize that it’s only a matter of time before the sole blocking point to Indexing 2.0 is the technology to implement it, which is a solvable problem (not to mention a helluva business opportunity!).

In fact, arguably this is the real “billion dollar idea” that robo-advisor platforms should be trying to tackle, which is relevant for any individual investor who holds investments and has to deal with taxes and would like a more granular opportunity to harvest losses (or gains) more opportunistically. And notably, this would not be a competition between robo-advisors and human advisors; it’s competition to brokerage platforms, custodians, and the multi-trillion dollar mutual fund and ETF industry for retail consumers (though not institutions, nor retirement accounts, that are generally tax agnostic), and is a solution that can be bought directly by consumers, or utilized by advisors on their behalf!

Perhaps the biggest target would actually be the trillions of dollars with Indexing 1.0 pioneer Vanguard itself (along with major ETF index providers Blackrock and State Street; how’s that for a TAM, Mr. VC?!). Indexing 2.0 represents the potential for a total disruption of the existing index fund and ETF industry, by the re-creation of all existing tax-efficient index funds in an even more tax-efficient manner! And "robo-indexing" may be a much better and more scalable business model than robo-advising or robo-allocating, as it’s easier to scale an end-client product that is distributed (via advisors, and/or directly consumers) than trying to compete as another distribution channel (and there’s a massive amount of money already sitting in “less efficient” index funds that could easily move to a comparable-cost-yet-more-tax-efficient solution!).

In addition, it’s notable that Indexing 2.0 doesn’t really have to be solely about classic market-cap-weighted indexes like the S&P 500. It could have tilts. It could be factor-based. It could reflect “smart beta”. It could even be done actively, if the active manager has direct access to change the target allocations on an ongoing basis to engage in “program trading” across all clients on the Indexing 2.0 platform committed to the strategy. This could skip right past the nascent Active ETF products, and eventually become a threat to not just the indexing side of the fund industry, but actively managed mutual funds as well (as the fund managers disintermediate mutual funds to implement directly with investors and their advisors in a more granular and tax-efficient manner).

Ultimately, it may still take a little more time for a true focused Indexing 2.0 platform to emerge (though arguably the Wealthfront 500 is basically "there" already, albeit as a 'side product' to their automated investment service 'core'), but given that transaction costs only continue to go down, and that the tax law fundamentally validates the business model but providing the most tax planning opportunities to the most granular portfolios, it seems only a matter of time before the 2.0 “robo-indexer” solution emerges. It's simply a matter of waiting until the costs for trading falls below the value earned with a more granular tax loss (or gains) harvesting strategy. Once the line is crossed - and we may nearly be there already, as the Wealthfront 500 shows! - more platforms can emerge to facilitate Indexing 2.0. It may be platforms that have the technology to facilitate the trading/management and an arrangement for the low transaction costs and allows other managers to utilize it for distribution (for a fee, of course!), or could simply be a platform that distributes its own core indexing-but-not-as-a-fund solutions.

In the meantime, stay tuned as we see whether one of the existing robo-advisors pivots in the robo-indexing direction, or a new player comes to the table (and for any platforms considering this massive blue ocean, let me know if you want some help building this; my advisory board dance card isn’t quite checked full, yet! 🙂 ). But it seems to only be a matter of time before the ongoing decline in transaction costs first spawned in 1975, pared with technology innovation that continues to reshape and commoditize many components of investment management, eventually begins to topple the very indexing industry it helped to spawn!

great piece.

Thanks, I hope it’s food for thought! 🙂

– Michael

It is, but it’s also a different business model and message and service model vs. much bigger players (Vanguard, DFA, iShares, WisdomTree to name a few) who are stacked with armies of wholesalers and retail salespeople, years of experience, mammoth marketing budgets, and current AUM (and ps, they’re also all cash-flow positive).

While these 1.0 online efforts have big piles of cash right now (and probably equally big burn rates) I’d argue that they also have a much more limited runway than they’d like still, so for them to burn the boats and pivot… (in some cases yet again) is a move I’m not sure we’ll see taken. 44,000 clients between FutureAdvisor, Betterment, and Wealthfront is a far cry from the 14 million household market they’re chasing. In some cases, they’ve been trying to crack this market for 6 years already. Does it happen in the next 5 to 10 years? I don’t know, but me thinks probably not. Me also thinks that none of the players have enough cash on hand to last that long, without more capital still.

Right now the money is in the banks and brokerage firms, and it wouldn’t take that much for them to offer something similar within a matter of a year or so, and with the infrastructure to do it. So what’s the moat?

I also see this as an evolutionary move, instead of revolutionary, which might be what is needed to finally make enough eyeballs (and wallets) open up.

The 2.0 indexing idea, while I agree is a great efficiency realization, also pushes the razors edge of simplicity. Even Index fund investors like seeing some complexity; meaning more than one ticker symbol on their statement (even if it is a false sense of security), but less than the 100 pages of statements needed to hold 500 companies as a quasi-SMA index fund.

I don’t have the answers, yet, and I don’t think these companies do either.

Me thinks if they were just raising money now (or better yet, boot-strapped with bigger adoption numbers), or in a few years they started to buy some of the carcasses of the fallen, maybe 2.0 could work.

We’re very early in the trend, but right now these companies are all starting to look like WebVan to me. Maybe a great idea, just ahead of its time.

Michael, could you explain a bit how you see tax-loss harvesting working on the individual level? If a stock in, say, the quasi S&P 500 portfolio is sold at a loss, what would you buy to replace it? Another company already in the S&P 500? One just outside it but in the same sector? I’m guessing that the ordinary index-fund investor wouldn’t know what to do, which puts it in the hands of the firm facilitating the construction of the portfolio or an advisor.

Also, transaction costs would have to come down to practically zero for this to work (not saying they won’t). E.g., buying an index fund at Fidelity costs $20. Replicating that for the Russell 2000 would mean a transaction cost of $0.01 per stock.

I suppose all of the detailed decisions can be (or already are) written into the software that manages the portfolio. So the advisor/investor can push a button to “harvest losses,” “take gains,” or “harvest loss and replace holding” etc. etc. Bottom line for the investor, though, is whether the after-tax, after-fee results are the same as holding a low-cost index fund, right (assuming those are the two alternatives being compared)? And how much more time/effort, if any, does the investor need to spend managing the portfolio versus the “old” way of using an index fund. Does the cost of the software (or software-using advisor) offset the (tax) benefits of using this approach?

Michael–

I’m a bit confused. If a person starts by holding all stocks in an index (or even a representative sample) and they later cherry pick which issues to sell (perhaps repeatedly), won’t they alter the degree to which the remaining unsold issues represent the original index?

Julian,

Any time sometime seeks to harvest a capital loss and avoid the wash sale rules, they must buy “something else” that is similar (but not substantially identical) and introduce the risk of “tracking error” during the wash sale period. I’ve written about this separately in the past – see http://www.kitces.com/blog/is-capital-loss-harvesting-overvalued/ – it’s a standard challenge for any loss harvesting, whether it’s an index fund or a particular underlying stock.

Notably, though, it’s only an issue with loss harvesting for high-income individuals, but not gains harvesting for lower income individuals, as there are no wash sale rules for harvesting gains.

– Michael

The S & P 500 Index is market cap weighted. That is an essential quality of the index. How will market cap weighting be maintained in Index 2.0, especially in conjunction with individual tax harvesting transactions?

Michael,

Completely agree. How close is MyVest to creating this platform?

You should be aware that I patented the Cambridge Index Strategy in 1998 which is similar (see http://www.CambridgeIndexStrategy.com. The minimum is only $100,000, and the expenses (paid to LJPR, LLC for management) are 22.5 bp. This index equally weights fifty individual stocks: the Dow (minus Phillip Morris — as requested by our doctor clients), as well as the top ten stocks in the NASDAQ and the top eleven in the S&P 500. This avoids fractional shares. All losses are harvested at the end of Oct. and parked in index ETF’s to avoid the wash-sale rule for 31 days +. Those stocks which appreciate more than 10% are moved to a separate “Greenhouse” account” in late Nov. In early Dec. the remaining ‘runts’ are sold and the combined with the funds from the parked ETF’s and new money the client contributes.

Besides harvesting losses, this allows highly appreciated stocks from the Greenhouse to be contributed to DAF’s, for grants to charity, saving capital gain tax. When parents or grown children need money, they are gifts medium appreciated stocks so the can be sold by the donee in a 15% bracket tax free, and the minimally appreciated stock are sold if needed for the clients cash flow (loss carryforwards offset the small gains).

We have used it successfully with clients for17+ years. It takes minimal management since transactions are limited to 4 per year. Analyses have shown it may outpace the S&P on an after-tax basis by 2-5%.

This is available through the Schwab Platform.

Fidelity does this at a lower minimum of 200k. Also they use 175-250 positions to mimic the index.

Is there a name for the Fidelity solution? I hadn’t seen their particular offering…

– Michael