Executive Summary

With the 1996 introduction of “tax-qualified” long-term care insurance under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and IRC Section 7702B, Congress affirmed that long-term care insurance benefits are tax-free, and began to offer tax benefits for purchased LTC insurance coverage.

However, over the years the evolving landscape of both individual tax deductions in general, and long-term care insurance tax preferences in particular, have created a confusing myriad of options to purchase LTCI and receive favorable tax treatment.

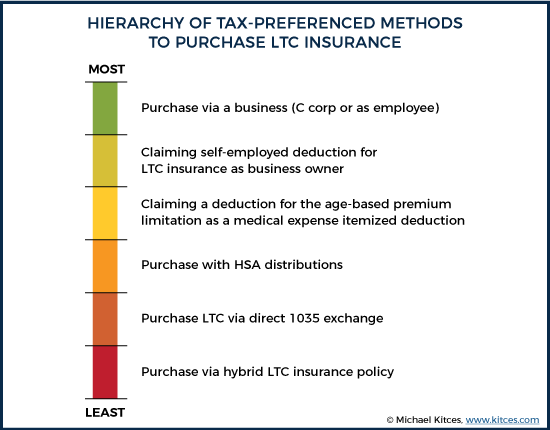

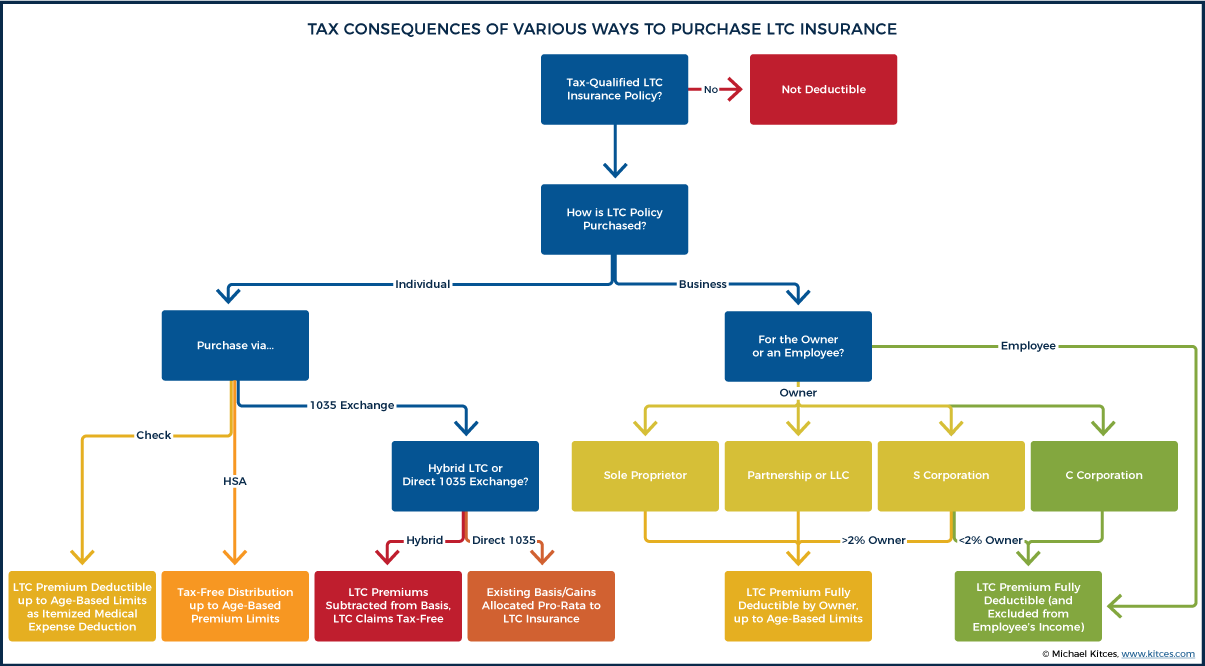

In this article, we explore the full range of options, from the most favorable (purchasing on behalf of employees, or for employee-owners of a C corporation or who are less-than-2% shareholders of an S corporation), to the slightly less favorable (purchasing for owner-employees of partnerships and LLCs, more-than-2% owners of S corporations, and sole proprietors), to the least favorable (paying for LTC insurance premiums directly, subject to age-based limitations, medical expense AGI thresholds, and itemized deduction limitations). And there are also the less-common-but-also-sometimes-appealing alternatives, like using the money in a Health Savings Account (HSA) to purchase LTC insurance, or funding it via a partial 1035 exchange into a standalone LTC insurance or hybrid LTC policy.

Ultimately, the reality is that some people won’t actually have many choices about how to pay for coverage – the choice will simply be whether to purchase or not, and write a check for the premiums as the only means eligible. Nonetheless, it’s important to understand the full breadth of options for how to pay premiums on LTC insurance, especially given the nuanced but substantial difference in tax treatment across the different choices!

Deducting Individual Long-Term Care Insurance Premiums

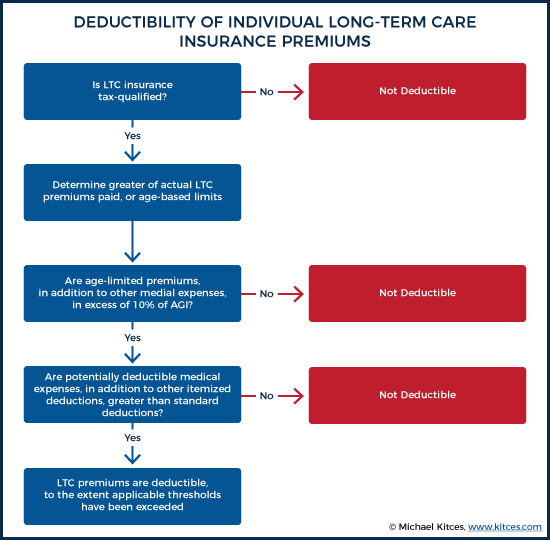

Under IRC Section 213(d)(1)(D), premiums for long-term care insurance are deductible along with other individual medical expenses.

Notably, to be eligible for deductibility, the long-term care insurance must be (tax-)“qualified” coverage (as defined under IRC Section 7702B(b)), though in practice virtually all long-term care insurance issued today (and in the past 20 years) is tax-qualified. (Non-Tax-Qualified, or NTQ long-term care insurance, is primarily characterized by either not requiring a minimum Activities of Daily Living restriction, or being more lax in the certification requirements to be eligible for claims.)

Premiums paid for tax-qualified LTC insurance are deductible if paid for the individual taxpayer themselves, his/her spouse, or any dependent as defined under IRC Section 152, which can include both dependent children and even dependent parents, if they otherwise qualify as dependents for tax purposes, and without regard to the must-be-unmarried or income tests that otherwise apply to a “qualifying relative” dependent.

While premiums are deductible, though, the amount of the deduction is limited.

First and foremost, the standard rule for medical expenses still applies – that in order to claim a deduction (for both LTC insurance premiums, and all other medical expenses, added together), the taxpayer must itemized deductions on Schedule A, and only the portion in excess of 10% of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) is actually deductible (as the 7.5%-of-AGI threshold expired at the end of 2016 under the Affordable Care Act).

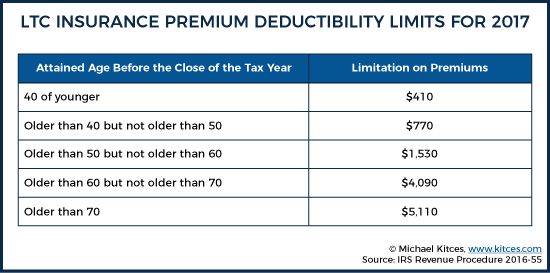

Second, in addition to the limitation on (total) medical expense deductions (including LTC insurance premiums), there is a further limitation on the amount of LTCI premiums that can be counted as a medical expense in the first place. Under IRC Section 213(d)(10), premiums can only be deducted up to a specific maximum annual dollar amount (which itself is annually indexed for inflation). The LTC insurance premium deductibility limits for 2017 are shown below, with age thresholds evaluated based on the taxpayer’s age at the end of the tax year.

Example 1. This year, Allen and Jennifer turned ages 62 and 59, respectively. Each recently bought a (tax-qualified) long-term care insurance policy. Allen’s policy costs $3,200/year, and Jennifer’s costs $2,800. As a result, in 2017, Allen will be permitted to deduct $3,200 (the cost of his policy, since it is below the $4,090 threshold), though Jennifer will only be permitted to deduct $1,530 of her premium (capped at the up-to-age-59 threshold). Which means in total, the couple can claim $3,200 + $1,530 = $4,730 of long-term care insurance premiums as deductible medical expenses. To the extent that $4,730, when added to other medical expenses, exceeds 10% of the couple’s AGI, the excess above the threshold will be deductible.

Next year when Jennifer turns 60, her deductibility limit will rise to $4,090, which is more than enough for her to deduct her entire premium. Thus, in the future, the couple’s LTC insurance premium deduction will rise to the full $3,200 + $2,800 = $6,000 (which, again, must be added to other medical expenses to determine how much above the 10%-of-AGI threshold is actually deductible). Notably, because the couple’s LTC insurance premiums themselves are less than the $4,090 limit (by the time they’re in their 60s), their deductions are still “capped” at the actual amount of LTC insurance premiums being paid each year.

Notably, as the above example illustrates, even if LTC insurance premiums have limited deductibility early on, the tax deductions may become more feasible later as the policyowner crossed the deductibility age bands.

In addition, because LTCI premiums are only deductible to the extent they exceed 10% of AGI, premiums may be partially or fully deductible in some years but not others, simply due to unrelated changes in income (that impact the AGI threshold). Conversely, significant shifts in other deductions can also indirect impact LTCI premium deductions, as none of them are deductible until/unless the taxpayer can itemized in the first place (rather than claiming the standard deduction). Which also means that potential tax reform proposals, which may substantially increase the standard deduction, could also reduce the deductibility of LTC insurance premiums, by making the standard deduction so high that few have enough LTC premium (and medical, and other itemized) deductions to reach the threshold.

In addition, some states also provide individuals with a tax deduction or small credit for purchasing long-term care insurance. In some cases, the deduction or credit is only for the first-year premium/purchase; in other scenarios, it is permitted on an ongoing basis (as long as premiums continue to be paid). Furthermore, some states have no limits on the amount of LTC insurance premiums eligible for the deduction or credit, while others conform to the age-based premium limitations. Individuals should check on the rules applicable in their particular state.

Paying For (And Deducting) LTC Insurance Through A Business

The rules and limitations on the deductibility of long-term care insurance are substantially different when premiums are paid through a business, rather than as an individual.

Under the general rules of IRC Section 162, compensation to employees is deductible to the business (which may include long-term care insurance), and the related IRC Section 106 stipulates that payments for “accident and health plans” (which includes tax-qualified long-term care insurance) are not included in the employee’s income, either. And under IRC Section 105(b), payments to reimburse medical expenses of an employee are not taxable benefits to the employee, and IRC Section 7702B(a)(2) stipulates that LTC insurance premiums will be treated as reimbursement for medical expenses… which means claims from employer-paid LTC insurance are not treated as taxable benefits.

The end result is that, akin to other employee benefits, a business’ payment of LTC insurance premiums on behalf of employees is a pre-tax expense for the business, without causing income to the employee that receives the coverage or claims benefits against under that coverage (though if the employee also pays some of the premium themselves, it is treated as after-tax and the out-of-pocket portion will only be deductible or not under the usual individual limitations).

However, to prevent abuses by business owners who may also be “employees” in their own businesses, the tax law imposes several limitations on the deductibility of long-term care insurance premiums for the business owners themselves.

Sole Proprietors

In the case of a sole proprietor, IRC Section 162(l) provides that long-term care insurance can be deducted as a self-employed health insurance expense, but the dollar amount of the deduction will be limited to the age-based premium limitations of IRC Section 213(d)(10) (as shown in the earlier chart). However, because the self-employed health insurance deduction is claimed as an above-the-line deduction (on line 29 of Form 1040) and not as an itemized deduction, sole proprietors paying for their long-term care insurance are not subject to the 10%-of-AGI limitation.

In the event that the sole proprietor purchases LTC insurance coverage for both themselves and a spouse, the age-based premium limits apply to both. However, if the spouse is a bona fide employee of the business, and the policy is purchased and paid for as employee compensation, the full amount of the premium can be deducted as a business expense (and only the owner’s LTCI premiums would face the age-based limitation). In addition, it’s notable that LTC insurance coverage provided to bona fide employee-spouse that also covers the sole proprietor employer may be fully deductible as employee-family coverage for both (e.g., where the business buys the employee-spouse individual coverage that has a shared-care family rider attached).

Partnerships (And LLCs Taxed As A Partnership)

In the case of a partnership (or an LLC taxed as such), long-term care insurance premiums paid on behalf of partners may be deductible to the business as guaranteed payments under IRC Section 707(c), but since partners are not treated as employees, the cost of the coverage must then be added back to the partner’s income (which means the net result may shift partnership income amongst the partners, but doesn’t directly produce any tax savings).

Subsequently, though, the partners are still treated as self-employed, which means they can personally deduct the long-term care insurance premiums as “self-employed health insurance” coverage on line 29 of Form 1040. As with sole proprietors, the deduction will be limited to the age-based premium restrictions, but as an above-the-line tax deduction, will not face the 10%-of-AGI or itemized deduction threshold requirements.

Example 2. Ashley and Sally are 50/50 members of an LLC that last year produced $200,000 of income, and the two want to purchase LTC insurance and “route” it through the business. Ashley is 57 and her LTC premium is $2,700; Sally is 62, and her LTC premium will be $3,700.

Absent the LTC insurance, their respective income shares as 50/50 partners would be $100,000. However, with the LTC insurance premiums being deductible as guaranteed, business income is reduced by $2,700 + $3,700 = $6,400 to only $193,600. With their 50/50 shares, this reduces income to $96,800. Then, Ashley and Sally must each include the premiums paid on their behalf in their respective incomes, which brings Ashley’s total income up to $99,500 and Sally’s up to $100,500. (Notably, total business income is still $200,000, but Sally’s taxable share is now slightly higher, due to the higher LTC premium.)

As a final step, Ashley and Sally may each deduct their LTC insurance premiums from their tax returns as a self-employed health insurance deduction. Due to her age, Ashley is limited to a deduction of just $1,530 of her $2,700 premium, while Sally is able to claim the entire $3,700 premium (since her age-based cap is as high as $4,090).

Notably, to get the favorable treatment for a partnership or LLC (where ultimately, the premiums are at least deductible as self-employed health insurance without the medical expense AGI or itemized deduction thresholds), the premiums must actually be paid by the business. If the business owners pay the premiums directly as individuals, they may still be subject to the standard rules for individual LTC insurance premiums (including the below-the-line medical expense limitations).

S Corporations

Under IRC Section 1372, a more-than-2% owner of an S corporation is treated as though he/she is a partner in a partnership, which means all the aforementioned rules apply – premiums paid may be deductible to the business, but must be included in the income of the more-than-2% owner, who may then claim the premium deduction as an above-the-line self-employed health insurance deduction (but only up to the age-based premium limitation).

In order to be treated as a more-than-2% owner, the shareholder must actually own more than 2% (not just exactly 2%), but the threshold is met if he/she owns more than 2% on any day of the taxable year (i.e., even if ownership changes intra-year, being a more-than-2% owner at any point in the year counts for that tax year).

In addition, the family attribution rules of IRC Section 318 apply when evaluating the more-than-2% ownership requirement. Thus, stock owned by a spouse, children, grandchildren, or parents (including indirect beneficial ownership via a trust) also counts towards meeting the 2% ownership threshold.

C Corporations

When it comes to a C corporation, the “standard” rules for employees continue to apply, including that long-term care insurance is deductible as part of compensation (as an “accident and health insurance” benefit) under IRC Section 162, and that the premium payments are not taxable to the employee under IRC Section 106.

Again, though, for favorable tax treatment, the premiums must be paid directly by the employer, not via a Section 125 cafeteria plan (as LTC insurance is explicitly denied favorable treatment under IRC Section 125(f)). And if the premiums are paid under a Flex Spending Account, the premiums become taxable to employees under IRC Section 106(c) (although then at least they could be deducted under the rules for individuals paying LTC insurance premiums).

In the case of a C corporation, there rules apply equally to owners and other employees, and there’s no less-favorable treatment for employee-shareholders. However, to substantiate the LTC premiums as a employee compensation business expense under IRC Section 162, the shareholders must actually be employees, doing bona fide work, and the compensation (including those LTC premiums) must be “reasonable compensation” (for the services rendered) to maintain its deductibility. In general, LTC insurance premiums are moderate enough that reasonable compensation shouldn’t be an issue, but be wary trying to allocate deductible LTC premiums to family member “employees” who don’t actually do much of anything for the business, and be cognizant that limited-pay LTC policies (e.g., 10-pay, 5-pay, or single-pay policies) that lump larger premiums into fewer years could potentially run afoul of reasonable compensation (although in practice such policies are rarely even available anymore).

In addition, while LTC insurance is not subject to non-discrimination testing as an employee benefit – which means it can be offered selectively to employees, including shareholder-employees – it’s still necessary to substantiate it as employee compensation and not just a shareholder dividend. As a result, eligibility to participate in the employer’s “LTC insurance employee benefit program” should not be based solely on whether the participant is a shareholder; instead, it should be determined based on other factors, such as providing to a “class” of employees (e.g., officers of the corporation), based on a particular length of service, etc.

Alternative Tax-Preferenced But Non-Deductible Strategies For Paying LTC Premiums – 1035 Exchanges And HSAs

Beyond the rules for deducting long-term care insurance premiums as an individual, or via various types of businesses, there are a few other ways that LTCI coverage can be purchased in a tax-preferenced manner, including via a Health Savings Account (HSA), an annuity 1035 exchange, or a hybrid LTC insurance (or annuity) policy.

Paying LTC Insurance Premiums From An HSA

Under IRC Section 223, contributions to a Health Savings Account (HSA) are tax-deductible, the account grows tax-deferred, and distributions are tax-free when using for “qualified medical expenses”. And while the HSA qualified distribution rules generally only apply to medical expenses – and not medical insurance – IRC Section 223(d)(2)(C)(ii) explicitly states that (tax-qualified) long-term care insurance premiums are eligible.

However, since IRC Section 213(d)(10) limits the portion of LTC insurance premiums that can be treated as “medical expenses” to the age-based limits, only LTCI premiums up to those age-based limits can be withdrawn tax-free from an HSA as qualified medical expenses. Which means any “excess” premiums above the age-based thresholds must be paid out-of-pocket (not with HSA dollars).

In addition, it’s notable that under IRC Section 223(f)(6), any medical expenses (includes LTCI premiums) paid via a Health Savings Account cannot also be claimed later as a medical expense itemized deduction. In other words, LTCI premiums (up to the age-based limits) can be deducted as an individual medical expense, or paid for with a tax-free HSA distribution, but never get both favorable treatments for the same premium dollar.

Paying LTC Insurance Premiums Via A 1035 Exchange

The Pension Protection Act of 2006 modified the “like-kind exchange” rules of IRC Section 1035(a) to allow life insurance and annuity contracts to be exchanged for a long-term care insurance policy. Up until that point, annuity policies could only be exchanged for other annuity policies, and life insurance policies could only be exchanged for other life insurance or annuity policies.

Under the new rules, though, an existing life insurance or annuity policy could be 1035 exchanged for a (tax-qualified) long-term care insurance policy. The existing policy must be a non-qualified annuity or life insurance policy (i.e., not held inside of an IRA or employer retirement plan).

Of course, given that life insurance or annuity policies often accumulate significant cash value, while the premiums on long-term care insurance are far more modest (at least on a relative basis), in most cases the exchange would just be a partial 1035 exchange of some life insurance or annuity cash value for an LTC insurance policy.

Fortunately, Revenue Procedure 2011-38 affirms that partial 1035 exchanges are permitted, and when they occur, gains and basis are simply allocated pro-rata between the old and new contracts. Though since a long-term care insurance generally has no cash value, the gains allocated to the LTC insurance policy effectively vanish without every being taxed.

Example 3. Charlie has a $120,000 existing non-qualified annuity contract with a cost basis of only $70,000 (and thus an embedded gain of $50,000). He is also purchasing a (qualified) LTC insurance policy with a $3,000/year premium. Under the existing 1035 rules, Charlie can fund his LTC insurance premium with a partial 1035 exchange for $3,000, reducing the cash value of the annuity to only $117,000 and the cost basis to $68,250 (since the transfer is treated as $70,000 / $120,000 * $3,000 = $1,750 of basis, and the remaining $1,250 of gain). Thus after the exchange, Charlie’s embedded annuity gain has decreased from $50,000 to just $48,750, as $1,250 of the gains are ‘shifted’ to the LTC insurance policy. Yet since the exchange was tax-free – as a 1035 exchange – and the LTC insurance has no cash value to liquidate, the end result is that the $1,250 of gain is simply eliminated.

Unfortunately, one major caveat for doing a 1035 exchange to an LTC insurance policy is that to complete the transaction, the existing annuity or life insurance company must directly assign the policy (or part thereof) to the new LTC insurance company, which in turn must be capable of accepting, processing, and liquidating the assigned share. In practice, not all LTC insurance companies have the systems in place to do so, and thus may not be willing to permit or cooperate with a partial 1035 exchange. If the insurance company cannot facilitate the transaction, the opportunity is simply unavailable; it cannot be done by merely taking a distribution and “rolling it over” to an LTC insurance policy, if the 1035 exchange is not facilitated directly.

Nonetheless, for companies that do permit an incoming partial 1035 exchange, the strategy can help to whittle down otherwise taxable gains. Which is especially appealing in the case of an appreciated non-qualified annuity, given that such annuities remain taxable even after death (to the beneficiaries) and do not receive a step-up in basis, providing no other alternative to eliminate the embedded gain.

(1035 Exchanging Into) Hybrid LTC Insurance Policies

The last option for funding LTC insurance on a tax-preferenced basis, also introduced as part of the Pension Protection Act (PPA) of 2006, is to do a 1035 exchange from a(n appreciated) life insurance or annuity policy, into a “hybrid” version of a life insurance or annuity policy that includes an LTC insurance rider. Specifically, PPA 2006 modified the definition of what constitutes a “like kind” exchange under IRC Section 1035(b) to stipulate that it’s permissible to exchange into a life insurance or annuity policy that has an LTC insurance rider, and still be treated as “like kind” as long as the exchange would have otherwise been permitted into a similar policy without such a rider.

The advantage of this strategy is that, under IRC Section 72(e)(11)(B), any charges for the LTC insurance rider against the insurance or annuity policy are not treated as a taxable distribution. (By contrast, without these rules, subtracting LTC insurance premiums from the cash value of life insurance or an annuity would have generally been treated as a taxable withdrawal.) Instead, the premiums are simply subtracted from the cost basis of the policy.

Notably, the fact that the premiums subtracted from the hybrid policy already receive preferential treatment, they may not also be claimed as a medical expense deduction under IRC Section 7702B(e)(2). However, claims paid out for the LTC portion of the policy can also be received tax-free (as LTC insurance benefits), even if they otherwise would have been a taxable distribution from the policy’s cash value. This is likely to be a more favorable treatment than “just” taking a taxable distribution from the insurance or annuity policy directly, paying long-term care expenses, and trying to claim a medical expense deduction later.

Example 4. Continuing the prior example, Charlie decides that instead of doing partial 1035 exchanges to an LTC insurance policy from his non-qualified annuity with $120,000 of cash value and a $70,000 cost basis, he will do a full 1035 exchange to a hybrid annuity/LTC policy instead. After the exchange, his $120,000 is invested into a new hybrid annuity/LTC policy, and carries over his $70,000 cost basis. Shortly thereafter, his first $3,000 premium is subtracted from the policy’s cash value, which reduces his cash value to $117,000 and the cost basis to $67,000.

Notably, after the LTC insurance premium is paid, he still has a $50,000 gain exposure; unlike the prior scenario of exchanging to an LTC insurance policy directly, the potential gain is not reduced. However, if Charlie subsequently has an LTC insurance claim, and uses the $120,000 to cover his long-term care expenses, he will not owe any taxes on the liquidation of his entire cash value, despite the $50,000 gain, because the LTC claims are still able to be distributed tax free. On the other hand, if he never actually has a claim, in the future Charlie (or his heirs) will still need to contend with the $50,000 embedded gain (plus any subsequent growth that occurs in the future).

Given that LTC premiums in a hybrid policy are only subtracted from basis (not gains), and the embedded gain is only reduced when actual claims are paid, an exchange to a hybrid policy will be most appealing in situations where there is an existing contract, with substantial embedded gains, and a relatively high likelihood of actually using the dollars for future claims.

Ultimately, the Internal Revenue Code provides a substantial number of different ways to purchase LTC insurance with favorable tax treatment.

In general, the “most favorable” rules are to purchase via a business that allows for the full deduction of LTC insurance premiums without any age-based limits (though that is only available for employees, C corporations, and 2%-or-less owners of S corporations).

The next best alternative, which at least maximizes the deduction – albeit subject to the age-based limits – including claiming a deduction for LTC insurance as a business owner (self-employed, partner or LLC member, or more-than-2% owner of an S corporation), or via a Health Savings Account.

After that, the most appealing remaining option is to purchase as an individual, claiming a deduction for only the age-based premium limitation as a medical expense itemized deduction (subject to the associated limits).

And in some cases as a last resort, it may be appealing to purchase the coverage either via a direct 1035 exchange, or what is often the least favorable (but still better than nothing!) treatment of using a hybrid LTC insurance policy. Though the greater the existing embedded gains, particularly in the case of a non-qualified annuity, the more appealing this strategy may be!

So what do you think? Do you explore tax-preferenced options for purchasing long-term care insurance with your clients? Is the landscape of tax-preferenced options too confusing? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Exceptional explanations Michael. The deductible chart is tied to the Medical Cost Index, my same chart runs for past ten years to demonstrate the rising premium deduction thresholds over time. It provides a good visual as the Insured ages into higher deductible age plateaus. For some life policies situations, we also surrender dividends down to policy cost basis-such that all gain is then used to pay the LTC policy premium for the Insured. We then take the cost basis proceeds from the life policy, and use it to acquire a variable annuity contract for the other spouse (typically the wife) who had no permanent life policy. We then 1035 exchange from the VA each year to pay for her LTC premium. Only caveat being there must be gain within the new VA contract in order for use to 1035 exchange dollars out of the VA to pay her LTC premium. Thus, we created a qualifying contract to pay her LTC premiums going forward, with otherwise taxable VA pro-rata gains distributed out of the contract-income tax free via the 1035 exchange.

Michael, Very valuable article. But you didn’t mention alternatives like Lincoln Moneyguard, which many of my clients have elected to use for funding LTC.

Isn’t MoneyGuard just a hybrid policy?

The only way to use “tax-favored” dollars to pay for a hybrid (like Moneyguard) is to do a 1035 exchange from another cash-value life insurance policy into the Moneyguard. Keep in mind, if they surrender the Moneyguard, there will be tax consequences.

Scott,

True, although claims for LTC purposes could/would consume the embedded gains tax-free at least. If they have LTC claims.

– Michael

I have substantial concerns about hybrid LTC policies, and have discussed them separately on this blog. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/is-the-ltc-cost-guarantee-of-todays-hybrid-lifeltc-or-annuityltc-insurance-policies-just-a-mirage/

But in the context of discussing tax deductions for LTC, the premiums for hybrid LTC aren’t deductible, so it didn’t fit in this context anyway. 🙂

And technically, the fact that hybrid policies allocate internal LTC costs to basis (and NOT gains) actually makes them the least favorable way to pay for LTC from a pure tax perspective – it’s REQUIRED to be 100% AFTER-TAX dollars, no pre-tax premiums at all. :/

– Michael

Hey Michael… As it relates to IRC 7702B(e)(2). Does that also remain the same if the policyholder continues to pay premiums into that hybrid policy? For example, if the policyholder pays $5k a year into a hybrid policy for the first 10 years. I suppose it would depend on if the LTC cost was charged against the cash value or deducted from the premium payment made.

Very well done, Michael. We’ve shared it on all of our social media.

Hi Michael –

Great read.

On the topic of paying LTC insurance premiums via a 1035 exchange, in the example you give, what is to stop someone from converting the entire annuity into a single premium LTC policy (cost of $120,000)?

It is clear that in the event of a small 1035 (such as your example), the amount moved out tax-free results in a reduction of basis, however, by converting the entire account, have you removed all potential taxable monies?

Feel like I am missing something.

All best!

In today’s market, the primary constraint is simply the lack of single premium LTC policies in the marketplace. :/ But in theory, it’s (still) possible, if the LTC carrier can accept/facilitate the 1035 exchange.

Either way, the (partial) 1035 exchanges to LTC move a pro-rata share of basis and gains. So yes, if you want to move all the gains, you have to move all the money. 🙂

– Michael

National Guardian Life offers a single-pay LTCi policy.

Excellent post, Michael! Wouldn’t it be great if NAIFA and ACLI and CFP Boards all lobbied for “above the line” deduction of these premiums? I believe there would be a fairly positive fiscal effect on Medicaid outlays by states if consumers could simply deduct these premiums. State partnerships are a great concept, but we need carriers to write this coverage and it doesn’t seem to be going in that direction.

Chris Acker, CLU, ChFC

http://myfasttermquotes.com

Hi Chris, the excellent LifePlans study commissioned by AHIP, “The Benefits of Long-Term Care Insurance, and What They Mean for LTC Financing,” (11/2014) attempted to put a number on this.

Their estimate: each inforce LTC policy saves Medicaid $6,681 over its lifetime. Given a total inforce cohort of 7.4M policyholders, this could save the program $49.4B. (Savings for new buyers in 2010 are higher– $7,917 per policyholder/lifetime.)

Cheers,

Stephen D. Forman, CLTC

@ltcassociates:disqus

Excellent reply, Stephen. Thanks for the info on the 2014 study. We, as a society, should really think about allowing above-the-line deductions for LTC insurance policies since this insurance saves so much money for the medicaid system. “A penny wise, pound foolish” it seems…

Very well done, Michael.

As a practical matter, re: this statement, “On the other hand, if he never actually has a claim, in the future

Charlie (or his heirs) will still need to contend with the $50,000

embedded gain (plus any subsequent growth that occurs in the future,” this is true because Charlie purchased a hybrid annuity. But it’s been my experience that most sales activity taking place thus far has been hybrid life. In that event, Charlie’s heirs will avoid the $50,000 embedded gain since the proceeds will be paid as a death benefit. (I don’t have sales figures at my fingertips, so it may very well be that we simply run in different circles.)

While we’re on the topic of hybrid life, it’s worth noting there is one carrier which structures its QLTCI (extension of benefits) as a 7702B rider which is funded separately by the client, and thus deductible under traditional QLTCI rules outlined above.

Best regards,

Stephen D. Forman, CLTC

@ltcassociates:disqus

Question for anyone – if a 60 year old who has a HSA purchased LTC Insurance with a $2,000 annual premium we know they could pay the annual premium and then be reimbursed by their HSA in the amount of $1,530, the age based limit. That means $470 of the premium was paid with “after-tax” $$’s.

When next year rolls around they now have higher LTC reimbursement limits – $4,090. Can this person be reimbursed for the $2,000 PLUS the $470 from the previous year?

Great article Michael. Question: Do all the same tax benefits apply for a joint LTC policy where both spouses are covered? Assuming a best case, c-corp scenario.

Excellent review of the tax preferenced options to purchase LTC. Thank you.

Question for anyone. If sole proprietor pays LTC premium and deducts as adjustment to gross income, can sole proprietor take a tax-free distribution from his HSA equal to the deducted LTC premium? Does result change if a portion of the LTC premium is nondeductible under IRC 213(d)(10)? Does the excess above the deduction limit qualify for HSA tax-free distribution?

I have been sole proprietor for many years and have deducted my long term care ins premiums. now that I am retired can I still deduct them?

Please explain Form Form 1099 LTC.

How to determine if proceeds are taxable or not

And Taxable vs Non Taxable policies.

Wonderful article. Informative special to those people that are not familiar on how to maximize Tax Deductions For Long-Term Care (LTC) Insurance.

James Martinez

https://healthywealthfit.com

From the very informative article:

“In addition, it’s notable that under IRC Section 223(f)(6), any medical expenses (includes LTCI premiums) paid via a Health Savings Account cannot also be claimed later as a medical expense itemized deduction. In other words, LTCI premiums (up to the age-based limits) can be deducted as an individual medical expense, or paid for with a tax-free HSA distribution, but never get both favorable treatments for the same premium dollar.”

My LTC premiums were not deducted on my federal tax returns, but I do get a 20% credit on my state return. Does this disallow me from using a tax-free HSA distribution to pay for my LTC premiums?

Thank you.

Excellent article. However, I have I’ve been living under a rock? I was under the impression it went back to the 7.5% of AGI for health expenses? https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc502

I did just realize this was written in 2017 so that makes sense. 😉