Executive Summary

Industry benchmarking studies can be a valuable tool for advisory firm owners to make better business decisions. By compiling and publishing data on firms across the industry, the studies enable owners to compare their firms’ performance side-by-side against that of their peers, giving the owners an expectation for how their firms should perform and insight into where they might be outperforming or underperforming the competition.

But despite the potential benefits, many firm owners choose not to use benchmarking studies. For some, this may be because the firm owners’ financial data might not be organized in a way that is compatible with participating in the survey and comparing to the results. For others, the sheer amount of data a benchmarking study provides may make it difficult to determine exactly which data points are most effective to track. And for still others, the amount of time required – from aggregating and submitting the firm’s financial information, to reading the study and comparing the firm’s performance with its results – can represent an obstacle to using benchmarking studies.

All three of the above issues, however, can be resolved with a systematic approach towards participating in and using industry benchmarking studies. By organizing the firm’s financial data to efficiently compare them with data from major industry benchmarking studies, focusing on a few key metrics that are the most relevant to the firm’s goals (rather than trying to compare every individual data point the survey provides), and – perhaps most importantly – knowing what the comparison with the benchmarking data actually says about the firm’s productivity, efficiency, and profitability, a firm owner can effectively use benchmarking studies to make decisions on how to further strengthen their business.

Furthermore, technological tools are emerging that can help reduce some of the time and resource burden on firm owners to track and analyze their financial data. Two such tools – AdvisorClarity and Truelytics – automate different parts of the process, and (depending on which part of the process the firm owner prefers to automate) either tool allows the firm owner to glean insight from benchmarking comparisons with less of an investment in time and resources.

Ultimately, the point of using benchmarking data is to better understand how an owner can improve their business. Because, while most advisors want to make their firms better in one way or another, they may not always understand which areas are already strong, and which could benefit most from improvement. By having an ‘average’ to compare against, it is possible to quickly see where these improvements can be made – meaning that the initial time investment of using benchmarking studies could ultimately save the firm owner a lot of time and effort in making their firm more profitable!

Many financial advisors are familiar with the concept of a benchmark from the field of investment management. In that sense, benchmarks are used to compare the performance of assets like stocks, funds, and managed portfolios against the broader market. But advisory firm owners can also use benchmarks as a way to assess the performance of their own firms: in this case, as a way to compare an individual firm against the industry as a whole (or against smaller peer groups within the industry).

The ability to compare a firm's performance with what might actually be expected from them – given the performance of similar firms – has valuable uses for making business decisions to improve profitability and achieve the owner's goals. Accordingly, financial advisor industry benchmarking studies exist as a way to compile and publish benchmarking data for advisory firms to compare with their own financial data.

But many financial advisory firm owners don't participate in, or otherwise use, benchmarking studies because they fail to see the value in having a benchmark to compare themselves to (or at least, they value it less than the time it would take to compile data and fill out benchmarking surveys). But skipping out on benchmarking studies may represent a missed opportunity, in that benchmarking data can hold the answers to many of the questions that advisors have about improving their business – including, most importantly, "How can I make my firm more profitable?".

With better knowledge about what benchmarking studies can say about a firm's financial health, which benchmarking data to consider when making comparisons to the firm's own metrics, and how to streamline the process as much as possible in order to reduce the resource burden for participating and using benchmarking studies, firm owners may find benchmarking studies to be a valuable tool for the process of making sound, data-driven decisions for improving their businesses.

Benchmarking Studies Help Firms Assess Their Financial Health By Comparing Themselves With Their Peers

Many advisory firm owners have a bookkeeping or accounting system in place for their firms. At the most basic level, firm owners use these systems to generate the financial data essential to the firm's everyday operations. This can include tracking business income and expenses for tax purposes, complying with state and SEC rules for maintaining books and records, and simply ensuring there is sufficient cash flow to pay the firm's employees and vendors.

A firm's financial data, however, can also provide valuable insights that the firm owner can use to make better business decisions. For example, firm owners can track how their income and expenses evolve over time and ensure the business is maintaining (and hopefully growing) its profitability from year to year. And by comparing the firm's numbers over multiple time periods (e.g., from quarter to quarter or year to year), firm owners can quantify their business's growth and understand – at the very least – whether or not it is moving in the direction they want it to go.

But advisory firms don't exist in a vacuum, and while the firm's data on its own can tell the owner how the business is currently performing, it gives no broader indication of how the business should be performing. To achieve this, firms need a reasonable measuring stick – i.e., a benchmark – to help them compare their financial data against the average of the firms in their industry (and ideally against those similar to their own, accounting for traits like annual revenue or number of employees).

Benchmarking statistics set an expectation for how a firm should reasonably expect to perform in certain key areas, so firm owners can know where they stand relative to that expectation. Firm owners can use this information to better understand their firms' strengths and weaknesses so that they can both nurture their stronger areas and continually work to improve the weaker ones. For this reason, numerous organizations undertake annual benchmarking studies to help owners assess their firms' performance against their peers.

In general, benchmarking studies send out surveys to gather data on revenue, expenses, staffing, client demographics, and many other data points for hundreds of firms across the industry that choose to participate and self-report their data. That information is then compiled, analyzed, and published in a report. The report usually outlines high-level insights about key metrics or industry trends, but often also includes an appendix with more granular data from the study to allow firms to dig deeper into their own analysis.

Though multiple organizations conduct benchmarking studies (including RIA custodians such as Charles Schwab and Fidelity, and professional networks like XY Planning Network), one of the best-known benchmarking studies – and the only one open to all RIAs, broker-dealers, and hybrid firms – is the InvestmentNews Pricing & Profitability Study (whose yearly report has a sticker price of $999, but is provided for free to firms that participate in the study).

The InvestmentNews study is notable both for the depth of information it compiles and for the way that the data is presented. It includes categorized breakdowns of different types of revenue and expenses, as well as average compensation, client numbers, and staffing levels. These metrics are then sliced into numerous cross-sections of different firm types, such as by business model (i.e., RIA, Broker-Dealer, and Hybrid models), annual revenue level, and the number of employees.

This sliced-and-diced format allows firm owners to compare dozens of different data points for their firms against the industry as a whole, as well as against firms more specifically similar to their own – giving them a more customized measuring stick against which to compare their own data and to make assessments about the performance of their business.

What Benchmarking Studies Can Tell Business Owners About Their Business's Profitability

While benchmarking studies can provide a wealth of information against which firm owners may compare their own metrics, the sheer quantity of data included in many benchmarking studies (with the InvestmentNews study being a notable example) can present its own challenge: How can a firm owner use all of that information to improve their business without devoting excessive amounts of time to access it?

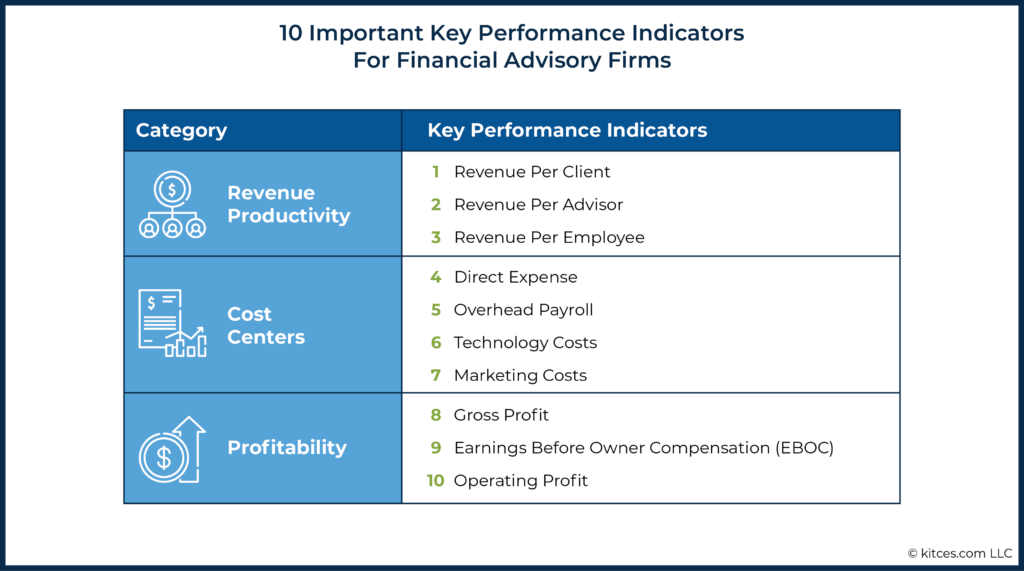

In fact, by following a few simple steps, firm owners can systematize their use of benchmarking studies to efficiently participate in and analyze the results of benchmarking studies to help them improve their businesses. The first step is deciding which data points are the most relevant to the firm's overall goals (and should therefore be the focus when comparing with the benchmarking study). A handful of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) can be easier to track year-by-year than the dozens (or potentially hundreds) of line items on a firm's profit and loss statement, and for this reason, owners often use KPIs to track their own firms' performance over the years.

KPIs can also be applied to benchmarking studies. Each line item in the benchmarking study may or may not be relevant to a firm's big-picture financial goals; instead, it is more efficient to focus on only the few metrics that are most impactful, and that will give the owner a bigger-picture view of how their firm measures up to similar firms in the industry.

Firm owners who already use KPIs to gauge their firms' performance over time, then, have a ready-made set of their most impactful data points which they can also use for comparing against their industry peers – or, put another way, if a firm owner has already decided which metrics are most important to reach their goals, then those metrics are also the natural starting point to compare with industry benchmarking data.

For firm owners who don't already use KPIs, the 10 Key Performance Indicators listed in the table below, divided into three categories by the types of information they provide (and subsequently described in further detail), are a good starting point for making an effective comparison with benchmarking studies.

Revenue Productivity Metrics

Firm owners can use revenue productivity metrics to gauge how effectively the firm uses its resources to generate revenue. One of the most important productivity metrics is Revenue Per Client, which is calculated as follows:

Revenue Per Client = Total client revenue ÷ Number of clients served

Revenue Per Client is simply the average amount of revenue that the firm receives from each client. Some firms use this metric internally to assess how individual clients compare with the 'average' client (often as a way to implement segmented service tiers or transition out the firm's least-productive clients).

But for advisory firm owners (and solo practitioners in particular), Revenue Per Client has an additional purpose: It provides an effective cap on the amount of revenue that the firm can generate. This is because there are limits on the maximum number of clients that any one advisor can effectively serve. At a given level of Revenue Per Client, then, the maximum amount of total revenue the advisor can generate is reached when the advisor reaches their full capacity of clients that they can sustainably service. After that point, the only way to increase Revenue Per Client would be to either increase fees charged to clients or to transition less productive clients out of the firm.

Example 1: Martha is a solo advisory firm owner with 25 clients and a total annual revenue of $250,000. Her Revenue Per Client is therefore $250,000 (annual revenue) ÷ 25 clients = $10,000.

Martha estimates her maximum capacity to be 50 clients. So the maximum revenue she could earn solely by adding more clients – assuming those clients generated, on average, the same amount of revenue as her existing clients today – would be $10,000 x 50 = $500,000.

However, If she were able to increase her Revenue Per Client to $15,000 (either by bringing on new higher-revenue clients, raising fees across the board, or transitioning away from her least-productive clients to bring in clients who will produce more revenue), her maximum potential revenue would increase to $15,000 x 50 = $750,000.

Benchmarking studies often include the average Revenue Per Client as an industry-wide metric. This gives firm owners a way to judge how their client productivity (and therefore their firm's maximum potential revenue) compares with other similar firms. For instance, in the 2020 InvestmentNews Pricing & Profitability Study, the median solo advisory firm had $8,080 of Revenue Per Client.

If the advisor in Example 1 above compared her Revenue Per Client with the benchmarking study, she would see that her current level of $10,000 is already above the median of $8,080. If she is providing a particularly valuable service to a specialized niche, she may be able to sustain an even higher Revenue Per Client level; however, if the Revenue Per Client reaches too high of a level, she may experience difficulty retaining her existing clients (who at some point may move on if they realize they could be served less expensively with another advisor).

For firms with multiple advisors, the Revenue Per Advisor (or Revenue Per Professional) metric measures the average amount of revenue managed by each advisor. As with Revenue Per Client, Revenue Per Advisor can be used internally within the firm to assess individual advisors against the firmwide metric, or it can be compared against the average of its peers using a benchmarking study.

Assuming that the firm's advisors are at their full capacity to serve clients, a Revenue Per Advisor number that is substantially lower than the benchmarking study's average can indicate that the firm is 'over-serving' its clients – that is, the services the firm is providing to its clients may be time-consuming enough that its advisors reach their capacity at a lower level of revenue than the average advisor at a similar-sized firm. This may indicate a need to tier or ‘right-size’ the services the firm provides to the level of fees it charges, so it is not substantially under-charging compared with the value of its services.

The third key productivity metric, Revenue Per Employee, measures the average amount of revenue supported by all employees (advisors and non-advisors alike). For larger firms with support staff, in addition to advisors, it is an indication of how well the firm is scaling its staffing costs as it grows in size. Firms with a lower-than-average Revenue Per Employee level are more staff-heavy in proportion to their revenue, indicating the firm may not be as efficient at providing services to clients as its peers.

Advisory Firm Costs

For firm owners trying to improve their profitability, tracking the firm's major cost centers against a benchmarking study can be a way to quickly find the most impactful areas to improve.

Consider that a business's profit (before taxes) is calculated as follows:

Profit = Revenue – Expenses

As the above equation shows, revenue and expenses are equally important to profitability: A dollar of increased revenue and a dollar of decreased expenses each have the same effect on net profit. But while both options are equally effective in theory, in practice, the expense side of the equation is where it is often more effective for a business owner to make immediate changes. This is because the owner has ultimate control over how to spend the business's money, but less control over how others spend their money on the business.

For example, while the firm owner can decide whether to retain or fire a particular vendor (giving them the ability to cut back on expenses as needed), they cannot force clients to retain the firm (resulting in less leeway to generate extra revenue by raising fees, since clients could respond by leaving for a less-expensive advisor).

Different advisors may have their own preferences for which expenses to prioritize, but some of the major costs common to many firms (and which can have an outsized impact on profitability) include:

- Direct expenses (e.g., advisor compensation)

- Overhead staff (e.g., administrative support and back-office employees)

- Technology costs

- Marketing costs

Most major industry benchmarking studies include information on how much participating firms, on average, have spent on these categories, both in raw dollar totals and as a percentage of the firm's revenue. Firm owners can use this information to compare their firm's expenditures against the industry averages. Major discrepancies between the firm's own data and benchmarked values might indicate where a firm owner can (or should) make changes to use the firm's resources more effectively.

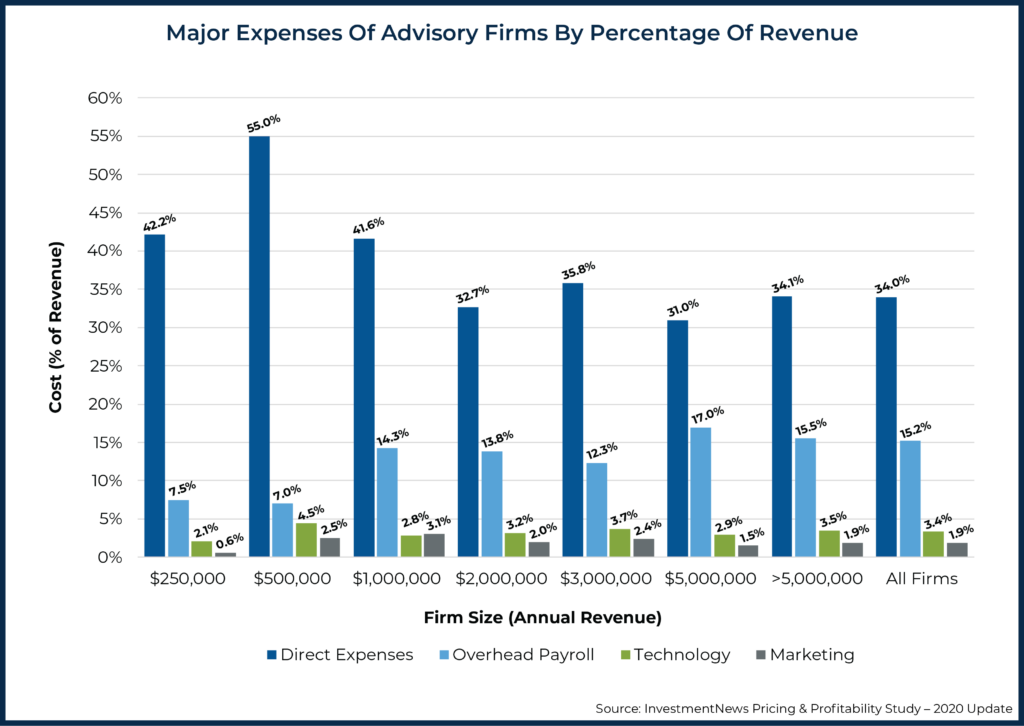

A benchmarking study that breaks down data by firm size can be particularly useful for comparing expenses because some of the major cost areas can differ dramatically depending on the amount of revenue the firm generates.

In the chart below, some of the key cost categories are shown as a percentage of revenue for firms of different sizes. As the chart shows, direct expenses (i.e., the cost of compensating advisors who directly generate revenue for the firm) make up a higher proportional cost for firms with less than $1 million in revenue than for larger firms, while other types of overhead costs are typically lower for the smallest firms but increase with the firm's size.

What's also notable is that the data compiled for all firms looks quite similar to the numbers for firms with more than $5 million in revenue. This is because larger firms tend to make up a greater proportion of the participants in benchmarking studies, such that, in aggregate, the studies' numbers tend to skew toward the averages for larger firms. Which makes it especially important for smaller practice owners to compare themselves against similar-sized firms, since doing so can give a very different impression of the firm's performance from comparing themselves against the total for all firms.

Example 2: Magill, Inc. is an advisory firm with $400,000 in revenue. The firm had direct advisor compensation expenses of $160,000, equaling $160,000 ÷ $400,000 = 40% of its revenue.

A benchmarking study revealed that the median firm spent 34.8% of revenue on direct expenses. In comparison to this median value, based on all firms participating in the study, Magill's 40% revenue spent on direct expenses would seem to be higher than that of the average firm.

However, when Magill's owner, Nancy, assesses benchmarking data from other firms with $250,000–$500,000 in revenue, similar to their own revenue, she finds that the average revenue spent on direct expenses was 50.8%.

Thus, Nancy concludes that Magill's expenses (40% of revenue) are actually substantially less than the median firm (50.8% of revenue) once size is factored in.

A large difference between an individual firm’s numbers and the benchmarking study average does not necessarily mean that a change is needed. For example, a firm spending more on technology than others in its peer group may use that technology to reduce the amount of back-office staff needed to provide its services, resulting in lower overhead costs and higher profitability overall. Rather, data points with large discrepancies can be flagged for further study, and for firms that do spend more than average on certain costs, with no corresponding increase in revenue or overall profitability, comparing with benchmarking studies can help spot those differences and know where to take action.

Profitability

For many firm owners, profitability is the end goal of owning an advisory firm. Profitability is what translates into the advisor’s take-home income (which, as Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing has shown, contributes more to the advisor's ultimate wellbeing than revenue alone). It also represents a business owner's financial return on their investment and plays a key role in how a firm is valued for a potential sale.

Furthermore, improving profit margins on an ongoing basis can be a key way for advisory firms to weather challenging business conditions, particularly AUM-based firms who can experience unexpected dips in profitability when financial markets decline.

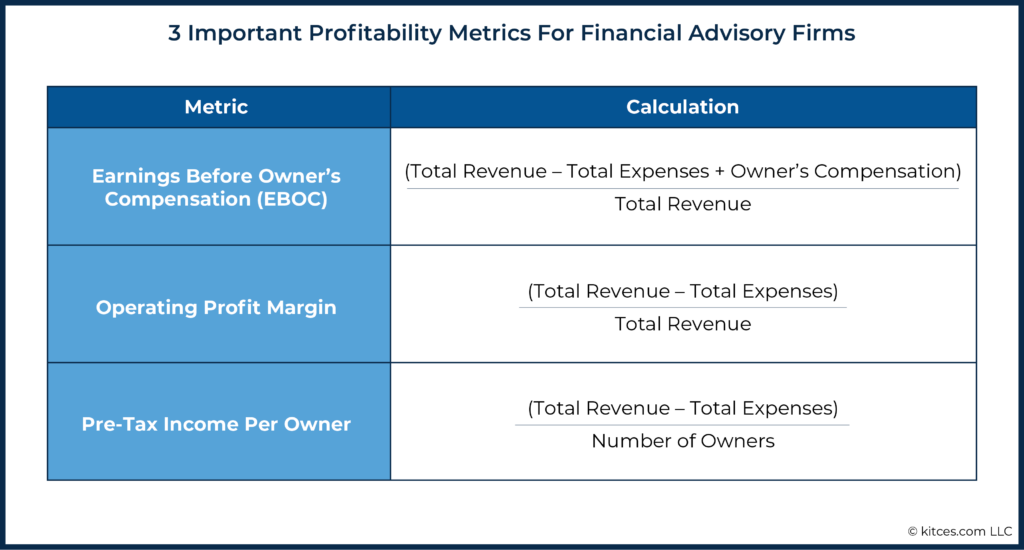

By using industry benchmarking data, a firm owner can compare the profitability of their own firm against that of their peers. The key profitability metrics that firm owners can track include Earnings Before Owners' Compensation (EBOC), Operating Profit Margin, and Pre-Tax Income Per Owner.

Earnings Before Owners' Compensation (EBOC)

EBOC is a measure of a firm’s profitability before taking into account any compensation for the firm’s owners. It, therefore, represents the share of revenue that is available for the owners to pay themselves, whether in the form of a salary or profit distributions (which is why EBOC is often used for comparing different firms since, in practice, owners usually have wide discretion in how they choose to pay themselves).

Put another way, EBOC measures the firm’s operational efficiency: The higher the firm’s EBOC, the smaller the proportion of its revenue is taken up by overhead and (non-owner) advisor compensation costs (and therefore leaving more take-home income for the firm owner).

Operating Profit Margin

Operating profit margin takes Earnings Before Owners' Compensation (EBOC) and adds back the value of the work that the owner does for the firm to show what is remaining as profit to the owner of the firm.

This distinction is important because advisory firm owners often serve the firm's clients as advisors (along with all manner of administrative and back-office work, depending on how large – or small – of a support staff the firm has). This work has value to the firm since hiring outside staff to perform those services would cost money, which would increase the firm’s expenses and decrease the profit ultimately realized by the owner.

So a firm’s 'true' profitability (i.e., the reward for simply owning a profitable advisory firm) accounts for the owner's compensation for their work (as an advisor, executive, manager, etc.) as part of the firm’s total expenses, with what remains representing the owners’ bottom-line profits.

Pre-Tax Income Per Owner

Pre-Tax Income Per Owner simply divides the operating profit (in dollar terms) equally between each of the firm’s owners.

This metric is important for firm owners because it represents how much income they can actually expect as profit for owning an advisory firm, and comparing their own Pre-Tax Income Per Owner value with data from benchmarking studies can reveal how a firm owner’s bottom-line income compares with owners at similarly sized firms.

Putting It Together: A Profitability Case Study

All three profitability metrics – EBOC, Operating Profit Margin, and Pre-Tax Income Per Owner – represent, to some degree, how efficiently a firm can turn client revenue into take-home income for the owner(s).

Let's consider the following case study to see how a firm uses industry benchmarking data to gain key insights about profitability metrics reflecting their own firm's operations.

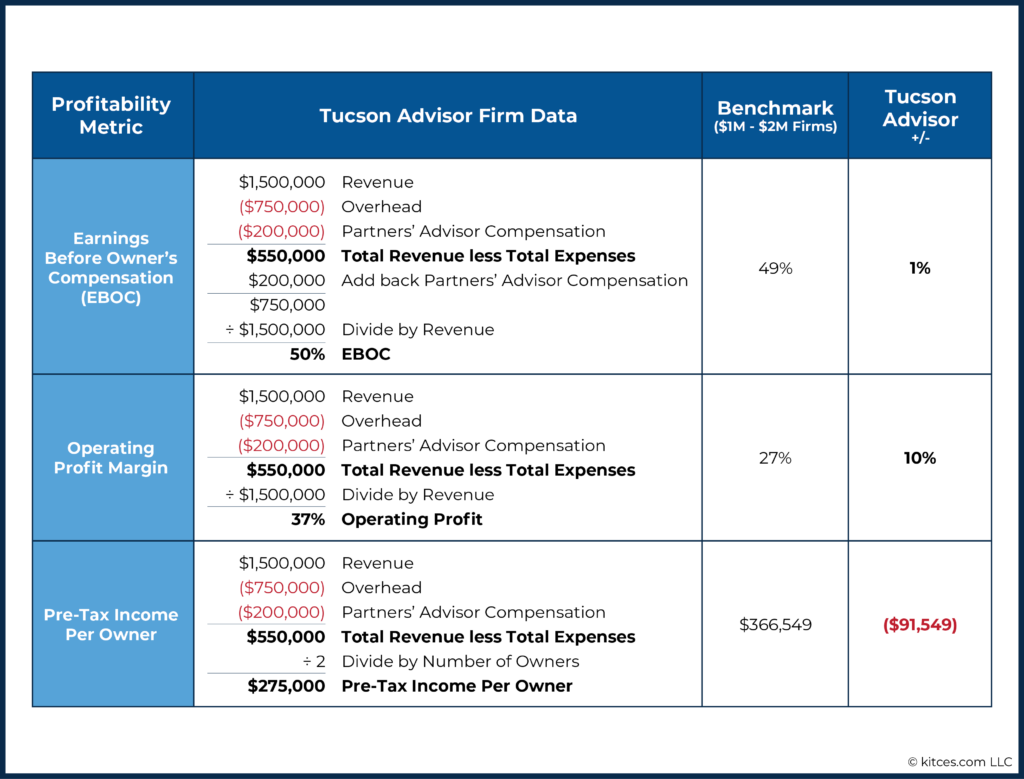

- Jo and Loretta are two equal partners in the advisory firm they own, Tucson Advisors.

- They each take a $100,000 salary from the firm and split the remaining profits.

- Tucson's financial data for the previous year show the following:

- Total Revenue: $1,500,000

- Overhead Expenses: $750,000

- Partners’ Advisor Compensation: $200,000

Tucson compiles the following information after comparing their profitability metrics to data from the 2020 InvestmentNews Pricing & Profitability Study:

Comparing each of the firm's profitability metrics with the benchmarking data reveals three key insights:

- Earnings Before Owners' Compensation (EBOC). From an operational standpoint, Tucson is performing similarly to its peers. Tucson's EBOC of 50% is in line with other firms with between $1 million and $2 million in revenue (with a median EBOC of 49%), showing that the firm is not overspending or underspending on overhead expenses relative to its size. However, as detailed further below, the fact that Tucson has multiple owners means that it may need to realize a higher EBOC than its peers – which likely include solo advisory firms that have no need for splitting profits – for each of its owners to realize profits in line with the owners of similarly sized firms.

- Operating Profit Margin. The firm's operating profit margin is higher than that of its peers by 10 percentage points. Since the only difference between EBOC and operating profit is the value of the advisor's services for the firm, this suggests that, relative to advisors in other comparable firms, Jo and Loretta may be undervaluing their work for the firm. Which means that its 'true' profitability might really be less than its profit and loss statement suggests: A higher salary for each partner ($172,500, compared with their current salary of $100,000) would be needed to reduce the firm's current operating profit margin in order to bring it closer to the 27% profit margin reported for comparable firms in the benchmarking study. In practice, this would be relevant if another firm were considering buying Tucson, since valuations are often calculated in multiples of operating profit.

- Pre-Tax Income Per Owner. Despite that Tucson's EBOC is essentially equal to the benchmarking study median and its operating profit is higher than the median, Jo and Loretta actually realize lower profits per owner than their peer group. There could be several reasons for this. For instance, the firms in the $1–2 million group could have higher revenue, on average, than Tucson, which could translate into higher profits (in dollars) for their owners, even with the same profit margins. Alternatively, some firms in that group are also likely to be solo practices (with no need to split profits between multiple owners), which could also result in higher profits per owner. Whatever the cause, Jo and Loretta do not realize as much income from profit as owners of similar-sized firms, and they would need to decrease expenses (specifically overhead expenses, since, as detailed above, they are already underpaying themselves for their advisory work) to get back to earning as much as their peers.

How To (Efficiently) Participate In Industry Benchmarking Studies

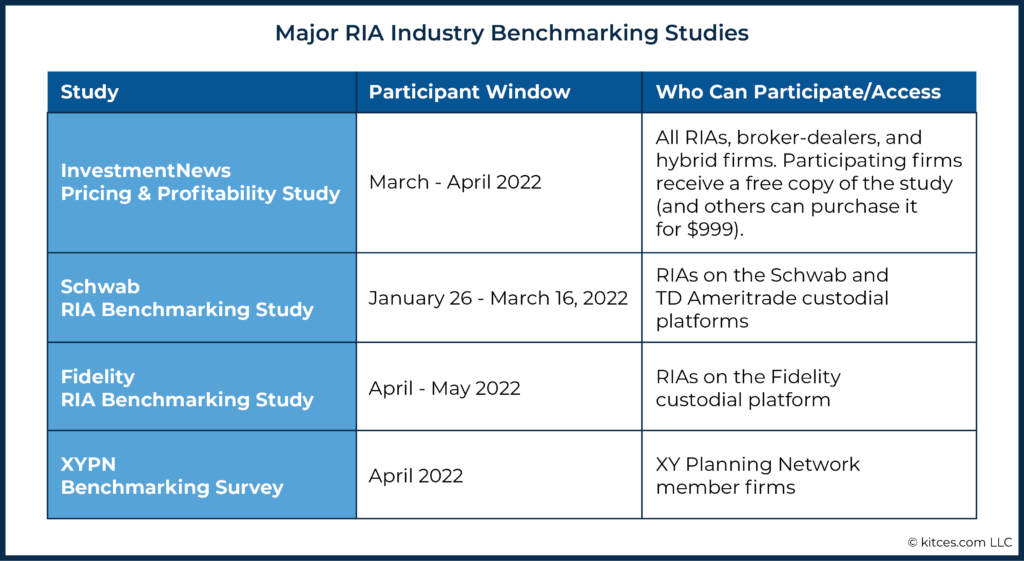

Several organizations currently conduct benchmarking surveys and publish the results on an annual basis. Some of the major RIA industry studies include the InvestmentNews Pricing & Profitability Study, Schwab RIA Benchmarking Study, Fidelity RIA Benchmarking Study, and the XYPN Benchmarking Survey.

Notably, the InvestmentNews study is the only one that is currently open to all advisory firms, regardless of custodial platform or professional membership affiliation.

Most surveys are open for participation each spring and ask participating firms to provide data from the previous year. For example, in order to participate in the 2022 round of benchmarking studies, a firm would need to finalize and compile its 2021 financial data in time for the participation window in the spring of 2022.

Since survey participation windows generally coincide with the individual and partnership/S corporation tax filing deadlines, it is likely that many firms will have the relevant survey data finalized at this point. Therefore, other than firm owners who regularly file for extensions, participants of benchmark studies generally wouldn't need to finalize survey data any earlier than they normally would.

Compiling Data For The Benchmarking Study

Benchmarking surveys often ask for extensive information about a firm's financial status, services, fees, and operations. The specific information can vary from one survey to another, but most benchmarking studies usually require the following information:

- Number of clients and Assets Under Management (AUM) as of year-end;

- Firm employee headcounts (broken down by owners, advisors, and support staff); and

- Financial transaction data (including categorized income and expenses for the previous year).

Client numbers can likely be tracked using the firm's CRM system, while year-end AUM should be available from the firm's custodial platform and/or billing provider.

Employee headcounts may be easy to determine for smaller practices since there might only be a handful of employees to count; for bigger firms, however, human resources or payroll departments would have the necessary data.

Financial transaction data can likely be pulled from the firm's bookkeeping and accounting system. But unlike client, AUM, and employee data (which are generally reported consistently across all firms), accounting data – specifically, the way transactions are grouped together and categorized – are often unique to individual firms depending on their owners' preferences for tracking and analyzing data.

For example, some firms may only track a few broad categories of expenses – like payroll costs, office expenses, and marketing – while others may go into more detail, breaking expenses into subcategories like software, rent, utilities, and website hosting (to name just a few).

To have reliable data to compare with the benchmarking study (and for the study itself to have viable data from the wide range of firms that participate), it's important for firms to have a consistent method of tracking financial data that provides the right level of detail for participating in benchmarking studies. Furthermore, maintaining a bookkeeping and accounting system that allows the firm to provide clear detail into their financial picture helps them to compare their own data against benchmarking metrics in a meaningful way.

Firm owners can set up their business's Chart of Accounts – the categorized list of accounting categories includes all of the types of income and expenses the firm may encounter – to facilitate participating in major industry benchmarking studies by aligning its categories to 'map' to those of the study. This Chart of Accounts template is designed to align with the InvestmentNews Pricing & Profitability Study (but can be adapted and implemented to meet the needs of specific firms).

Automating Parts Of The Process

Compiling financial data, calculating and tracking KPIs, and comparing them with industry peers can be time-consuming work for advisors alongside the day-to-day demands of client work, compliance, and the other requirements for running an advisory firm. While setting aside time for these tasks can result in valuable insights that potentially lead to a more profitable business… finding that time might be an impediment for advisors who want to remain focused on their client-facing roles.

Fortunately, like many time-consuming tasks, there are software tools that automate some of the manual steps of data collection, calculating, and reporting business metrics, and that help firm owners clarify and track progress toward their business goals. Two business intelligence solutions listed in the Kitces AdvisorTech Directory – AdvisorClarity and Truelytics – have arisen in the last few years that can help facilitate this.

AdvisorClarity is appropriate for advisory firm owners looking for a solution that automatically aggregates data from multiple sources (e.g., business accounting software like QuickBooks, portfolio accounting software like Tamarac, and CRM tools like Microsoft Dynamics) into a single 'dashboard' that calculates and tracks firm KPIs. Notably, AdvisorClarity itself does not provide comparisons to industry benchmarking data, but the tool can make the process of assembling and organizing the information needed much less time-consuming than the traditional method of compiling everything manually into Excel spreadsheets.

Truelytics, on the other hand, advertises itself as an "end-to-end" solution, which not only helps firms gather and calculate data to track KPIs, but also creates a "scorecard" that assesses and ranks firms against their industry peers by aggregating the data on every firm on Truelytic's platform. This essentially creates an ongoing benchmark study for Truelytics' own platform's customers, while at the same time automating the process of comparing the data and analyzing the results. However, Truelytics lacks the integration capabilities that AdvisorClarity has; instead, they require firm owners to manually gather and enter their own data (meaning the tool's time-saving capabilities may not be truly "end-to-end", since actually collecting the data is no more automated than it would be using an Excel spreadsheet).

The decision of which business intelligence tool to use, then, may ultimately come down to which part of the process the firm owner wants to automate: AdvisorClarity automates the data collection and aggregation steps through the tool's integration feature (while actually evaluating that data to make business decisions is left up to the firm owner); Truelytics, on the other hand, automates the step of actually analyzing and comparing the firm's data against peer firms (after requiring the advisor to compile the data – and ensure its accuracy – themselves).

The main point of data-driven decision-making is not just to collect the data itself, but to make the decisions based on the data available. Likewise, benchmarking studies are not valuable just because of the reams of data they provide, but because of how firm owners can use that data to improve their firms' profitability and achieve their business goals. Which suggests that collecting and analyzing the firm's data in comparison to benchmarking data is only the first step; the next step for firm owners is to use the results of those analyses to create a strategy that better enables them to reach their bigger-picture business (and personal) goals – much like advisors who first 'zoom in' on detailed analyses of their client's financial situation and then 'zoom out' from the details to ensure the client's overall goals can be met by realistic planning strategies.

But first – to actually get to the point where it is possible to create a plan – it is necessary to know what the data is saying. Revenue productivity metrics can help gauge how effectively a firm is using its resources to generate revenue. Analyzing major expense categories can show which cost centers the firm is prioritizing over others. And profitability metrics can show, overall, how well the firm is translating revenue into income for its owners.

Comparing each of their firm's own key metrics against the key metrics of other similar-sized firms in industry benchmarking studies can give the owner a sense of whether it is over- or under-performing based on what an 'average' firm would expect – because ultimately, while most firm owners would like to be above 'average' on the whole, it's only possible to do so when one knows where 'average' is to begin with!