Executive Summary

With the rise of 529 plans and increased focus amongst parents on saving for college, financial advisors have increasingly included college expense planning as a part of the comprehensive financial planning process for clients. And while the mathematics of funding education are relatively straightforward (at least in contrast to more complex retirement planning projections), the reality is that most advisors rely on some very simplistic college expense inflation assumptions for planning purposes (e.g., CPI + 3.0%). Yet, the increasing availability of college expense data reveals that the pace of inflation for college expenses may be slowing – at least for some types of college degrees – and that it’s necessary to take a more nuanced approach to college inflation assumptions.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – explores the historical data on the rising cost of a college education, and particularly the ways in which college inflation rates have varied based on institution type, location, and even the family income of the student.

For instance, according to the data in the Trends in College Pricing 2016 report (published annually by the CollegeBoard), the reality is that for students looking at private institutions, the common CPI + 3.0% inflation rate typically assumed by financial advisors has actually not been the case for some time now. Instead, the inflation rate for private colleges has been trending substantially lower for more than two decades! Yet by contrast, for high-income families looking at public institutions, a CPI + 3.0% inflation assumption for the cost of college may actually be too low!

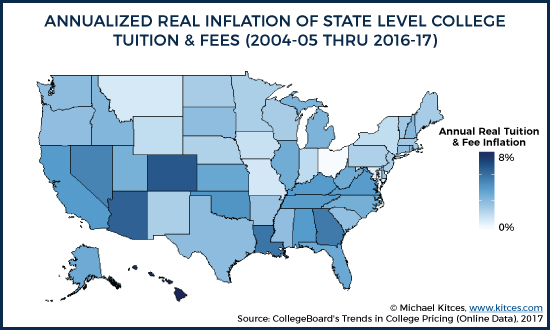

In addition to variations by institution type and family income, considerable variability exists by location. For instance, over the past 12 years, annual real college expense inflation at public institutions has ranged from a low of 0% in Ohio to a high of nearly 8%/year in D.C. and Hawaii. Additionally, location-specific trends are made more complex by the role that declining (or increasing) public funding has in increasing (or decreasing) the amount of aid that may be available to students to offset college expenses (which impacts the typical “discount” between the published cost of college and the actual net price that students typically pay).

Of course, just because we’ve seen trends in the past does not mean that those trends will be the same in the future, but particularly given the unique dynamics of college inflation rates for above-average-income families (who most typically work with financial advisors), and the risk that for some clients there may be several college inflation trends moving in the same direction that may substantial increase (or decrease) the savings that clients need to fund their educational goals, the annual CollegeBoard’s Trends in College Pricing report provides a tremendous amount of data that advisors can (and should) use to customize their college inflation assumptions!

Education Planning For College Expenses

With the increasingly burdensome cost of college, parents have become more interested in long-term planning for how to fund their children’s education. Which, in turn, has led financial planners to increasingly see college planning as an important value-add that can be provided to their clients in the financial planning process. And given that tuition inflation has continued to outpace CPI for some time now, setting an assumption for college expense inflation is crucially important for helping clients with their educational goals.

At its core, college expense planning is a fairly straight forward NPV calculation: How much does it take to fund four years of college expenses subject to some special rate of education inflation (to account for the above-CPI-growth rate in college tuition and related expenses)? In contrast to more complex financial planning methodologies that have been developed for retirement planning – such as historical analyses, Monte Carlo simulation, and dynamic programming – college planning seems almost painfully simple.

Once a student is in high school, parents generally at least have a decent idea of what’s next for the student. On top of that, both the timing and the expense are fairly predictable – at least for students who aren’t still many years out from college. Early on, advisors tend to make some basic assumption about college. For instance, attending school for 4 years, at age 18, based on the cost of either a particular in-state school (e.g., a major university) or the client’s own alma mater (“I went to State University and I want little Johnny to go there, too!”). All that’s left is to make assumptions about the growth rate of college savings and the inflation rate for the cost of college itself.

And yet, as many parents are beginning to save into vehicles such as 529 plans earlier and earlier, it is worth taking a closer look at college expense planning assumptions. In particular, the assumed inflation rate, as the reality is that the data in recent decades does not actually support some common financial advisor assumptions. Furthermore, the college inflations trends are not the same for all students, which means that assuming one standard college inflation rate runs the risk of over (or under) saving and potentially penalties (or shortfalls) that could leave parents unhappy when writing tuition checks or withdrawing excess college saving funds in the future.

Typical College Inflation Planning Assumptions

As rising college expenses have garnered much attention over the recent years, financial planners have typically assumed some college inflation rate that is materially higher than the general level of inflation (e.g., CPI + 3%) when planning for college expenses. With a long-term average inflation rate at 3%, this means a typical college inflation rates assumption of 6%.

But the reality is that college inflation varies significantly based on the income and wealth of the student (or at least his/her family), the location of the college, and even the type of educational institution they want to attend.

Examining Historical College Inflation Rates

The CollegeBoard’s Trends in College Pricing 2016 provides an extensive overview of changes in college pricing over time. Anyone deeply interested in this topic is encouraged to review this report in full, but some key findings are highlighted here.

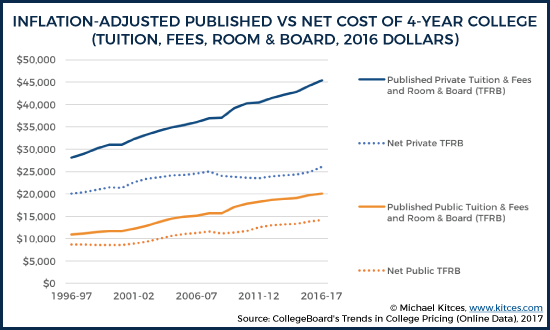

What does the data tell us about historical tuition inflation rates? First, many may be surprised by the current trends in pricing changes. For instance, looking back over the past 30-years, how would you guess current inflation-adjusted tuition inflation rates compare? If you guessed we are near 30-year lows, you would be correct!

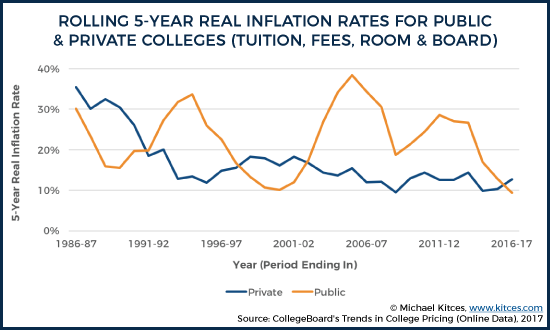

Of course, this is not the impression that many people have, but the five-year real change in published tuition, fees, and room and board from 2011-12 to 2016-17 was a cumulative 13% (2.4% annually) for private nonprofit four-year institutions and 9% (1.9% annually) for public institutions. By contrast, those inflation rates from 1981-82 to 1986-87 were 35% (6.2% annually) at private institutions and 30% (5.4% annually) at public institutions.

And notably, the rolling 5-year inflation rate at private colleges has hovered around 2.5%/year (or about 13% cumulatively over 5 years) for more than 2 decades now! Similarly, rolling 5-year college inflation rates at public institutions has been on a fairly steady downward trend since the early 2000s, though it remains to be seen whether inflation rates will remain at lower levels (as has been the case with private colleges) or rebound as they did coming out of the late ‘90s.

In other words, even though the “typical” assumption of financial advisors is for college costs to increase at a real rate of 3% (i.e., CPI + 3%), the real rate of change for college expenses is now below that level (and for private colleges, has been for almost 25 years now)!

Beyond this general trend of declining college inflation rates, though, there are at least three key sub-trends that financial advisors need be aware of as well: the variability of inflation by institution type, by location, and by income level of the student’s family.

Varying College Inflation By Type Of Educational Institution

The first factor to consider when helping a client determine the proper rate of college expense inflation is the type of institution their child is targeting. The Trends in College Pricing 2016 report analyzes many different types of institutions, each of which can exhibit different rates of inflation. For most advisors, the most relevant categories are likely:

- Public Four-Year In-State

- Public Four-Year Out-of-State

- Private Nonprofit Four-Year

Notably, the differences in published price levels between these groups are considerable. The average published price for public four-year in-state tuition, fees, and room and board was $20,090, whereas the same cost at private institutions was $43,870. Yet while it is generally well known that there are differences in price levels – and advisors can easily look these prices up for any target school a client is interested in – the reality is that the rate inflation for these costs going forward may also vary significantly!

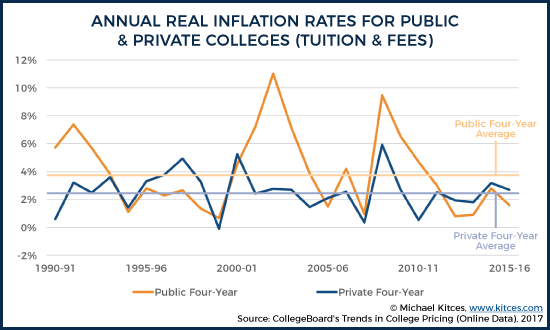

Based on the long-term data available, we can examine real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) increases in published tuition and fees going back through 1990-91 amongst public four-year and private (nonprofit) four-year institutions:

In contrast to the smoothed inflation rates first shown earlier, actual year-to-year inflation is noticeably choppier.

Looking at the historical data since 1990 allows us to make several observations. First, since 1990, changes in average published tuition and fees at public institutions has been more volatile than private institutions. In fact, the standard deviation of real changes over this time period was 2.8% for public institutions and 1.4% for private institutions.

This isn’t entirely surprising, though. Given that public institutions have lower price levels and may operate on the tighter budgets, it is likely that these institutions have less “slack” in their budgets, which may necessitate needing to make more immediate adjustments in pricing. By contrast, private universities, with the highest overall price levels, may be able to make more subtle adjustments in pricing (perhaps by economizing in other areas during lean times).

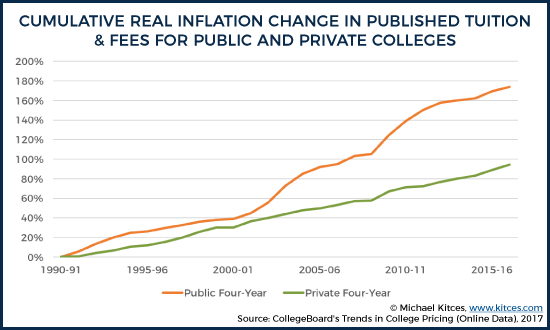

Additionally, when we examine the cumulative change in prices since 1990-91, it becomes apparent how different small divergences in inflation rates can be compounded over longer time horizons. The geometric average real inflation rates at public four-year and private four-year institutions were 3.95% and 2.59%, respectively. As a result, in real terms, published tuition and fees at public four-year institutions rose 274% since 1990-91 while the rate was only 194% at private four-year institutions.

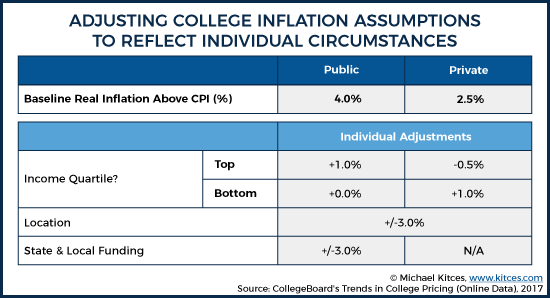

The bottom line: While the baseline cost of public universities is lower than that of private colleges, advisors may want to consider using a higher inflation rate for children planning to go to public schools rather than private colleges (e.g., 4.0% vs 2.5% above CPI, respectively).

Differences In College Inflation Rates By Location

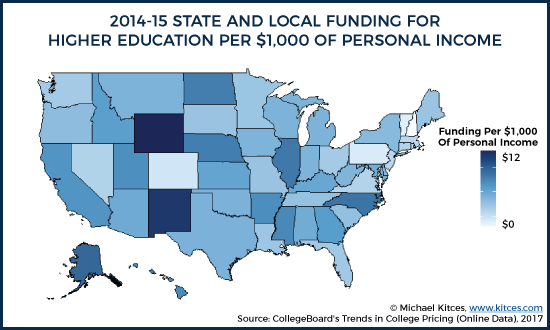

In addition to variation based on institution type, considerable differences in college inflation rates exist based on the location of the school.

From 2004-05 to 2016-17, cumulative real tuition and fee inflation at four-year public institutions ranged from a low of a 2% decline in Ohio (0% annually) to an increase of a 148% (7.9% annually) in Hawaii, followed by an increase of 145% (7.8% annually) in D.C.

Or, put another way, the geometric average real inflation rates of published tuition at public schools, on a state-by-state basis, have ranged from roughly 0% to 7.9% per year over the past 12 years.

Notably, though, the variability in state-level college inflation isn’t entirely random. There is a weak correlation (r = 0.43) between real price increases in four-year public tuition and fees between 2005-06 to 2015-16 and state population growth from 2005 to 2016.

Which suggests that about 19% of the variation in public tuition and fee growth might be predicted by population growth. Of course, prices generally wouldn’t be rising merely because of population growth, but it’s quite possible that population growth rates may be indicators of a state’s attractiveness as a place to live, including its attractiveness amongst youth as a college destination – potentially meaning that at least some colleges must (or can) raise their prices as a result.

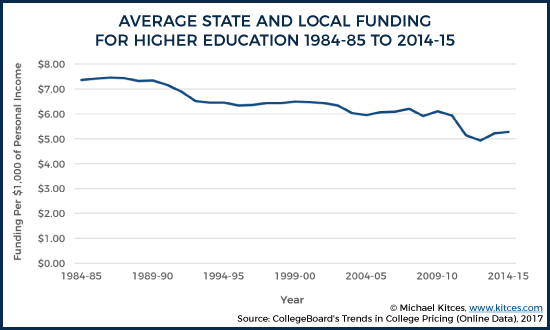

State and local finances also play an important role when it comes to in-state students at public universities. Trends in state level fiscal health and public policy can influence tuition inflation going forward. One notable trend is that, on average, state and local funding for higher education per $1,000 of personal income has been declining over the last 30 years

What this chart is showing is that from total state and local taxes (which average about $100 per $1,000 of income), a little more than 5% of that is going towards higher education. Of course, these levels (and the changes in these levels) vary by location as well. While overall funding per $1,000 of personal income was $5.28 nationwide, individual states ranged from a low of $1.59 in New Hampshire to a high of $11.41 in Wyoming.

Not surprisingly, decreasing state and local funding for higher education shifts the cost burden onto students, and we do see that reduced state and local funding is correlated with higher levels of tuition inflation (r = 0.34).

One additional factor included in the total cost of attendance (but not captured in tuition and fees) is room and board. Because of the localized nature of changes in economic factors which influence college prices at the local level (e.g., rental prices), specific local trends will tend to wash out in state level relationships (e.g., the trends in San Francisco are not the same as the trends in Fresno). Factoring in localized changes that influence the cost of college adds yet another level of complexity to planning for college expenses.

Of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean that previous trends will continue in the future, but the key point is that location does matter, and that lots of nuance is lost in the aggregate level statistics that are often used as the foundation for planning assumptions.

Variation In College Inflation Rates By Student/Family Income Level

While “sticker prices” (i.e., the official prices listed by a college) generally get most of the attention when it comes to education inflation, the reality is that these prices are only paid by a small subset of college attendees – most commonly, international students and domestic students with expected family contributions (EFCs) based on their prior-prior year incomes that eliminate them from financial aid eligibility. And notably, students with EFCs that eliminate them from financial aid eligibility are disproportionately the clients of financial advisors.

Accordingly, the CollegeBoard’s Trends in College Pricing 2016 report indicates that there’s a considerable gap between the sticker prices published and the prices students actually pay (even for relatively affluent students).

For instance, while average published tuition and fees for in-state students at public four-year institutions increased 41% (3.5% annually) in inflation-adjusted dollars between 2006-07 and 2016-17, average net tuition and fees – that is, what the average student actually paid after accounting for the aid they received – only rose by 30% (2.7% annually). In other words, nearly 25% of the increase in tuition and fees paid by the average student was actually covered by increasing amounts of student aid.

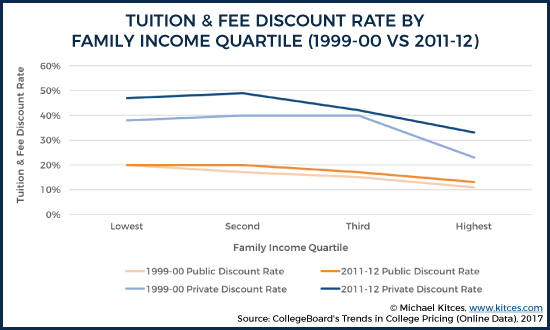

Notably, looking at the “average” student further masks considerable variability that exists amongst students given their family circumstances. For instance, while the average dependent student at a public four-year institution received a 16% discount off of published prices in 2011-12, a student whose family was in the lowest income quartile received a 20% discount, whereas a student in the highest income quartile received a 13% discount. Of course, even segmenting students into quartiles masks some of the true variability, as a student at the 76th percentile may not be receiving the same discount as a student at the 96th percentile (though some aid may be merit based, which, based on relationships between socioeconomic factors and criteria for awarding merit aid, disproportionately goes to wealthier students). But still, even top-quartile students are, on average, paying 13% less than the published sticker price of a public institution.

And the gap was even wider in private four-year institutions, with an average discount rate amongst students in 2011-12 of 39%, though the discount was actually 47% for students with families in the lowest income quartile, and 33% for students with families in the highest. In other words, even families in the highest income quartile are, on average, receiving discounts of 33% off of published prices at private colleges – and those discounts (in percentage terms) have been increasing over time.

Still, though, the pace of discounting has been more aggressive for lower-income students than upper-income students, which results in different inflation rates based on the income level of the student. As a result, the net real tuition and fees at four-year public institutions (in-state) rose by 41% (2.9% annually) for the lowest quartile families and 59% (3.9% annually) for the highest quartile families from 1999-00 to 2011-12. Which means that not only have the historical college inflation rates differed based on income, but that for the families that advisors disproportionately work with (highest quartile families), the “standard” 6% inflation rate (CPI + 3%) actually could be too low in some circumstances!

By contrast, at private nonprofit universities, tuition and fee inflation rates were actually lower for families in the highest income quartile. Real tuition and fee inflation rates (based on the net cost of private college) were 3.0% for families in the lowest quartile, but only 1.3% for families in the highest income quartile, over the same time period.

Making College Expense Inflation Assumptions In Practice

One of the main benefits of simple college expense inflation assumptions is that they are just that: simple.

Yet as the CollegeBoard’s Trends in College Pricing 2016 report so aptly demonstrates, there is a lot of complexity in understanding the true changes in college pricing over time. And while there’s always a risk that trends may reverse or may not be predictive of the future, the data still suggests it’s not best to simply use one rate of college expense inflation for all clients. In reality, we may want to at least “shade” our estimates in certain directions based on historical averages and current trends. And there are many situations where the standard “CPI + 3%” assumption is not a good fit at all.

Consider two examples where the underlying factors are the same with the exception of whether a student is interested in a private or public institution:

Example 1. Suppose a child is interested in a public college. We may start by looking at the average tuition and fee inflation at public four-year institutions since 1990-91. Since the geometric average real rate of tuition and fee inflation was roughly 4.0%, perhaps we feel comfortable starting with an assumption of CPI + 4.0%. Next, we note that the client is in the highest income quartile, which, in recent history, has experienced higher inflation rates by about 1.0 percentage point, so we bump the assumption up to CPI + 5.0%. Next, we note that, over the past decade, schools within the state of interest have lagged national inflation rates by about 0.5% (see CollegeBoard’s Trends in College Pricing 2016 for state-specific details), so perhaps we decrease the assumption down to CPI + 4.5%. Finally, we note that state budget cuts have been reducing funding available for education and there is little indication that trend will change soon, so perhaps we adjust the final estimate up to CPI + 5.0%.

Example 2. Suppose instead that the child is interested in private school. Since the geometric average real rate of tuition and fee inflation was roughly 2.5% since 1990-91, perhaps we feel comfortable starting with an assumption of CPI + 2.5%. Next, we note that the client is in the highest income quartile, which, in recent history, has experienced lower inflation rates by about 0.5 percentage points at private institutions, so we adjust the assumption down to CPI + 2.0%. Next, we note that, over the past decade, schools within the state of interest have lagged national inflation rates by about 0.5%, so we decrease the assumption further to CPI + 1.5%. Finally, though the state has recently seen budget cuts and there is little indication that trend will change, since state and local funding has less impact on private education costs, we make no adjustment for this trend (though perhaps similar trends regarding an institution's endowment and donor activity would warrant similar adjustments!).

Notably, the baseline inflation rate has been lower in recent history than what is indicated above and some of the relationships between different factors can be more complex than a simple chart can capture, but the key idea here is to illustrate the different steps and adjustments advisors may want to consider, customized to reflect their own views on college expenses going forward and the unique circumstances of their clients.

Of course, on average, we would actually expect different factors to cancel out in many cases (as that is quite literally what an “average” is getting at). Nonetheless, the most important thing to guard against is situations where all the indicators are mostly point in one direction – and to recognize that the inflation trends for above-average-income students is not always what one might expect (e.g.., the inflation rate for the net cost of private colleges for upper-income students has only been 1.3% since 1999, but lower-income students at public institutions are still trending at close to 3% inflation above CPI!). In other words, at least a subset of college students may need to be prepared for significantly higher or lower college expense inflation going forward than the average figures imply.

Additionally, advisors may want to spend some further time investigating current trends in both their local market and key college destinations for their clientele. Of particular interest may be states like California and Texas, which, according to the CollegeBoard’s Trends in College Pricing 2016 report, enroll 22% of the nation’s public college students. Additionally, the Census Bureau has lots of great data for looking at certain demographic trends, and most state governments provide fairly extensive information regarding local budgets online.

In the end, there’s no one right way to do college expense planning, but the data is available to help advisors try to identify trends and customize the all-important inflation assumption for college expenses to a particular client’s situation.

So what do you think? Should financial advisors use one college expense inflation assumption for all clients? What college inflation assumption do you use? Do you adjust inflation rates with your clients? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

I suspect this article will make some advisors’ heads explode as they’ve been used to the “simple” way of doing college planning. What a great way to use the trend in pricing report to provide valuable information to those of us doing real college planning!

I recommend 5% with the caveat that you monitor the annual cost changes for the school for which you are planning and apply that rate subsequently. This leads to the value of updating the plan each year rather than just setting it and forgetting it, as so many advisors do (probably not your readers, though!).

Fantastic article, thanks for digging into this topic and unearthing the nuance that should go into college planning for individual families. I did have one question. Doesn’t this assume that the child/student knows where they want to go from an early age? What if they change their mind during their senior year of high school and decide they want to try and go Ivy League while you (the parent/guardian) had been saving for what you thought they wanted, an in-state public institution? Do you explain to your child that you have this pot of money to help with their education and after that it’s on them? How would you prepare for that decision volatility? Keep up the good work, I appreciate the depth of your work!

That’s a good point, @zachreuter:disqus. If someone is very uncertain about where their child will ultimately go to college, then it is hard to do much customization. That said, there’s still a reasonable case to be made for paying attention to local trends. According to a footnote in the CollegeBoard’s online data (https://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/figures-tables/percentage-first-time-students-public-four-year-institutions-who-are-state-residents-fall ), the percentage of first-year college students going to school outside of their home state in 2014 ranged from a low of 10% in Utah and 11% in California to a high of 45% in New Hampshire and 48% in Vermont.

Interesting that the in-state college attendance rates vary so much, but I suppose it makes sense based on the size and location of your state as well as the quality/prestige of your ins-state options (UCLA and BYU vs. UNH and UV, for example). Appreciate the response and looking forward to your next piece.

Great data and observations here, Michael (as always). But instead of spending time picking the exact education inflation rate for clients, planners can do a much greater service by steering clients towards those schools where they can get the most needs or merit-based aid, whichever is appropriate. Lower the EFC if needs-based, and target schools that meet > 90% of need. For wealthy families, make sure the school target list includes only those that offer merit base aid, and apply to those schools where the student is in the top 25% academically to garner the most merit aid.