Executive Summary

Touted as the most significant update to the Internal Revenue Code in decades, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) did indeed introduce several noteworthy changes, including the new 20% qualified business income owners of (some) pass-through entities, a (much) lower corporate tax rate, a (much) higher estate tax exemption, lower individual tax rates for the vast majority of taxpayers, and a slightly higher total standard deduction (which combined both the existing individual standard deduction and the per household personal exemption). Ironically, though, while the TCJA legislation largely accomplished its objective of simplifying the process of filing taxes, it did so largely by making it a lot harder for households to itemize deductions at all going forward!

As while the new standard deduction isn’t that much higher than the combined prior standard deduction and personal exemption, the threshold for itemizing deductions in the first place is significantly higher than it was before, simply because the personal exemption wasn’t part of the equation when calculating the prior deduction threshold. Moreover, the TCJA also either eliminated completely or curtailed many of the most popular itemized deductions that got people over the hurdle to itemize in the first place, including moving expenses, many miscellaneous itemized deductions, and unreimbursed employee expenses (to name just a few). The end result: the number of households eligible to itemize deductions at all is anticipated to fall from approximately 30% of US households to “only” 10%.

Regardless, despite the upheaval, itemizing deductions is still a viable strategy to reduce overall tax obligations, and there are still six core deductions available to taxpayers, including: medical expenses (to the extent that they exceed 10% of Adjusted Gross Income – up from 7.5% in 2018); taxes paid to other governmental entities (both state or local municipality taxes as well as foreign governments, but with a $10,000 maximum deduction limit… regardless of filing status!); at least some types of interest paid (for not only mortgage interest – up to a $750,000 principal limit – but for investment purposes as well); charitable giving (but with limits); casualty and theft losses (but, for individuals, only if they were attributable to a Federally declared disaster); and other (miscellaneous-but-not-subject-to-the-2%-of-AGI-floor) deductions (such as gambling losses and Ponzi scheme losses, among others).

It’s important, meanwhile, to note that most of the still-available itemized deductions simply don’t occur regularly, and there are even fewer large enough to get taxpayers close enough to the new standard deduction threshold to make itemizing “worth it” on a recurring basis. Those items include big mortgages (particularly when mortgage rates are still at historically low levels), large ongoing charitable deductions (even though the deduction amount will necessarily be much less than the amount given), big state and local tax deductions (at least for individuals, where the $10,000 SALT cap gets them close to a standard deduction that is “only” $12,000), high margin investing (since interest paid on investments is deductible… as long as the returns on the investments are taxable in the first place), big long-term care events (which, while undesirable, can require large ongoing medical expenses), and significant stretch-IRAs that are eligible for the Income in Respect of a Decedent (IRD) deduction (to the extent that the IRA was inherited from someone who actually had to pay Federal estate taxes).

While few households will be able to meet the standard deduction threshold every year using just those big-ticket items, though, it is feasible (and perhaps even much more likely) that taxpayers will be able to itemize on an intermittent basis, by combining a few (or several) additional deductions on top of other (lower-but-recurring) deductions. For instance, a taxpayer might combine ongoing mortgage interest, property taxes, and state income taxes with a large charitable contribution to push past the standard deduction threshold in order to take advantage of additional tax benefits.

Ultimately, the key point to realize is that the combination of a higher Standard Deduction threshold and the curtailment of itemized deductions, makes it much harder to itemize than it once was (if only because the new standard deduction provided a more substantive and generous tax benefit in the first place). Yet while fewer households are able to itemize each and every year, some may still be able to do so, either on an ongoing basis, or at least intermittently by stacking infrequent clusters of additional deductions on top of recurring items that typically aren’t large enough to matter from a tax planning perspective. Which is important, because at the margin it’s still valuable to identify and plan for the (few) years where itemized deductions will still be available, as those are the years when there’s the most tax benefit to stacking any other possible “add-on” deductions on top for more tax savings!

The Higher Standard Deduction Threshold And Fewer Itemized Deductions After TCJA

In late 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, in what was intended to be a major round of “tax reform” that would simplify the Internal Revenue Code and the burdens of annual tax filing.

In practice, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) didn’t quite achieve its goal of broad and sweeping tax reform – at least for individual households – but it did substantively alter the landscape of claiming various types of itemized deductions… “simplifying”, but in the process also greatly limiting, the ability to claim itemized deductions at all.

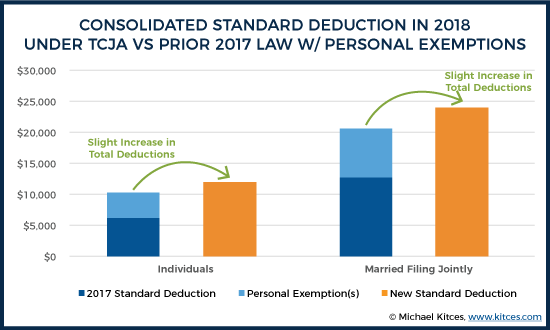

The key change under TCJA was the consolidation of what was previously a Personal Exemption of $4,050 per household with a then-Standard Deduction of $6,350 for individuals for a total of $10,400 for individuals (or $4,050 x 2 = $8,100 plus $12,700 in standard deductions = $20,800 for married couples), into a combined grossed-up Standard Deduction of $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for married couples… producing a slight increase in total personal-exemption-plus-standard-deduction tax benefits for most households.

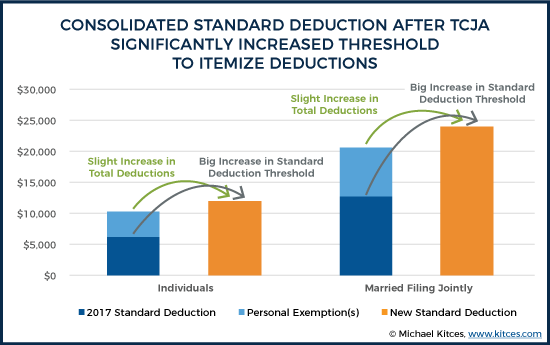

The caveat, however, is that while the new Standard Deductions under TCJA were only “slightly” higher than the prior combination of personal exemption(s) plus the standard deduction, the impact on itemized deductions was more significant. Because from the perspective of itemizing deductions, it only makes sense to do so when itemized deductions exceed the Standard Deduction (without any consideration for personal exemptions that weren’t included in that part of the equation).

Thus, while the new TCJA Standard Deduction was only a slight increase in total deductions, it was a big increase in the threshold to itemize deductions at all.

In addition to the significant increase in the threshold to itemize deductions at all, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act also reduced the number and size of available itemized deductions as well, including placing a $10,000 cap on State And Local Tax (SALT) deductions, a reduction in the maximum debt balance eligible for mortgage interest deductions to just $750,000 of debt principal (and an elimination of the deduction of interest on home equity indebtedness), curtailment of casualty and theft losses (to just those in a Federally-declared disaster area), and the repeal of the entire category of “miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the 2%-of-AGI floor” (which included unreimbursed employer business expenses variable annuity losses, tax preparation fees, and notably, the deductibility of an investment advisor’s own fees).

The end result of these changes: in the past, IRS data showed that approximately 30% of households were able to itemize deductions rather than claiming the standard deduction, but the Tax Policy Center estimates only about 10% of households will be able to itemize deductions going forward after TCJA.

The 6 Types Of Itemized Deductions That Remain After TCJA

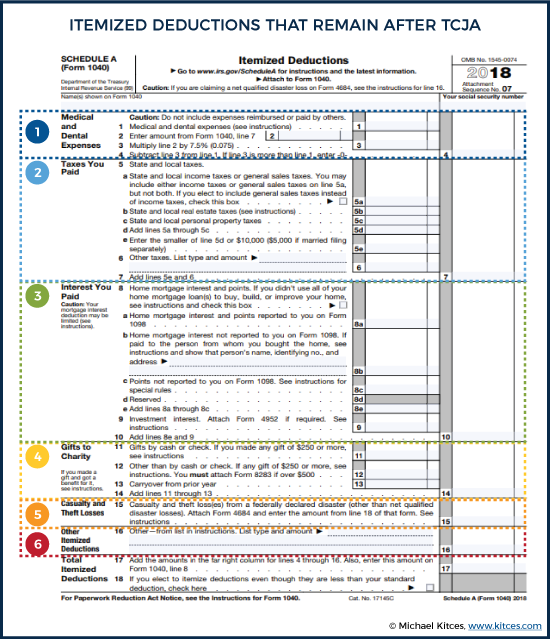

Notwithstanding the curtailment of itemized deductions after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, there are still 6 core types of itemized deductions that remain available for households to claim.

Per the delineation of Schedule A of Form 1040, the 6 types of Itemized Deductions are:

- Medical Expenses. IRC Section 213 allows for the deduction of a wide range of medical expenses, including payments for medical care (as well as dental care), health insurance premiums, and even a portion of long-term care insurance premiums. However, medical expenses are only deductible to the extent they exceed 10% of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) in 2019 (up from a 7.5%-of-AGI threshold in 2018).

- Taxes Paid To Other Governmental Entities. IRC Section 164 allows taxpayers to deduct for Federal tax purposes any taxes that were paid to other governmental entities (effectively ensuring that the individual doesn’t have to pay Federal taxes on the money they used to pay other taxes!). In practice, the deduction for taxes paid applies broadly to real estate taxes, personal property taxes, and income taxes, whether paid to a state or local municipality, or even to a foreign government (though under TCJA and IRC Section 164(b)(6)(A), foreign real estate taxes are not deductible), though it is commonly known as the State And Local Taxes (SALT) deduction. However, the taxes-paid SALT deduction is limited under IRC Section 164(b)(6)(B) from 2018 through 2025 to only a $10,000 maximum deduction (and it’s the same $10,000 whether individual or married filing jointly).

- Interest Paid. Under the general principle that borrowing money to make money should be treated as a cost of generating income (i.e., a deductible expense/cost of producing that income), IRC Section 163 allows a deduction for at least some types of interest paid. This includes not only interest paid for investment purposes (albeit limited the total amount of investment income generated from taxable interest and dividends in the first place), but also for mortgage interest paid on up to $750,000 of debt principal used to acquire, build, or substantially improve a primary residence or designated second home, and even mortgage points (that were paid out of pocket and not themselves financed).

- Charitable Giving. Under IRC Section 170, taxpayers are allowed to deduct charitable contributions made in the current tax year, whether donated in cash or as in-kind property. However, charitable deductions are subject to a number of limitations on the maximum amount that can be deducted (relative to total Adjusted Gross Income), depending on the type of receiving charity and the nature of the property being donated.

- Casualty & Theft Losses. Akin to allowing tax deductions for interest paid to generate income, IRC Section 165 also allows a tax deduction for losses incurred in income-producing activities (i.e., a trade or business). However, “personal” losses are much more restricted, though they may still be available in the event of a loss due to “firm, storm, shipwreck, or other casualty, or from theft.” Such personal casualty losses are subject to additional limitations, though, including that only losses above $100 for each incident are deductible, total casualty and theft losses must exceed 10% of AGI, and under TCJA from 2018 through 2025, IRC Section 165(h)(5) limits such losses to only those that were attributable to a Federally declared disaster.

- Other (Miscellaneous) Deductions. While the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act eliminated the category of “miscellaneous itemized deductions [subject to the 2%-of-AGI floor]” under IRC Section 67, there are still several other “miscellaneous” tax deductions that don’t fall into the preceding categories, but are still tax deductible because of their own separate standalone sections of the tax code to authorize them as deductions. This includes Gambling Losses (to the extent of Gambling Winnings), Ponzi scheme losses (and other similar casualty/theft losses of income-producing property), the income in respect of a decedent deduction for pre-tax assets inherited from someone who paid estate taxes, investment-related deductions for amortizable bond premiums and certain losses on contingent-payment or inflation-indexed debt instruments (e.g., TIPS), the unrecovered portion of basis in a pension or lifetime annuity that isn’t recovered when payments cease (e.g., due to death before life expectancy), and certain types of “qualified disaster losses.”

Ultimately, these 6 categories of itemized deductions are totaled on Schedule A, and in order for a household to actually itemize, the total across all 6 – after accounting for the various limitations that apply to several – must exceed the threshold of the Standard Deduction, in order to itemize.

Intermittent Itemizing And The Big 6 For Sustaining Itemized Deductions

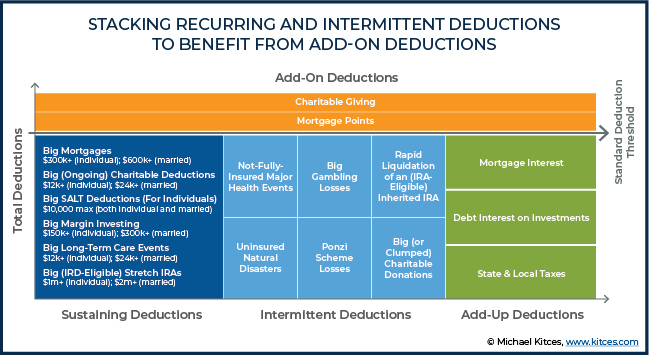

The significance of the fact that there are only a limited number of itemized deductions still available after TCJA, and that the threshold to itemized deductions at all is much higher than it once was (thanks again to the higher Standard Deduction under TCJA), is that in practice not only will only about 10% of households itemize deductions going forward, but only a subset of the available itemized deductions are ever likely to be a trigger to itemize in the future, and even fewer on a sustaining basis.

The Big 6 For Sustaining Itemized Deductions

The $12,000/$24,000 Standard Deduction hurdle (for individuals and married filing jointly, respectively, increasing to $12,200 and $24,400 in 2019) presents a significant challenge to itemize deductions, because only a few deductions in practice are capable of sustaining such a large deduction annually on an ongoing basis.

Accordingly, the Big 6 itemized deductions that can actually sustain ongoing itemized deductions include:

- Big Mortgages. Homeowners with a sizable mortgage that was used to acquire, build, or substantially improve their primary residence or a second home can generate enough in ongoing interest deductions to exceed the Standard Deduction thresholds. Notably, though, in an environment where mortgage interest rates have long hovered around 4%, it still takes a very sizable mortgage balance to actually generate enough interest to trigger itemized deductions, especially since it’s only the interest portion of the mortgage payment (not the entire mortgage payment) that is deductible. For an individual, generating a $12,000 mortgage interest deduction at 4% would require at least a $300,000 mortgage; for a married couple, the trigger is a $600,000+ mortgage.

- Big (Ongoing) Charitable Deductions. For higher income individuals who have significant financial wherewithal, it’s not uncommon for annual charitable giving to top the $12,000/$24,000 Standard Deduction thresholds (and at higher income levels, the charitable deduction AGI thresholds are not an issue to exceed these targets). Of course, giving away money just to get a tax deduction isn’t necessarily a net positive (as the household still gives more away than it receives back in tax benefits), but for those who already have a sizable ongoing charitable giving habit, sustained charitable giving alone can support ongoing itemized deductions.

- Big SALT Deductions (For Individuals). One of the unique peculiarities of the current tax planning environment is that when TCJA imposed a maximum cap on SALT (State And Local Tax) deductions, it imposed the same cap of $10,000 for both individuals and married couples. Which is significant, because the Standard Deduction threshold for individuals is ‘only’ $12,000 in the first place, while it is $24,000 for married couples. Which means maxxing out the $10,000 SALT deduction is at best only part of the way to the $24,000 threshold for married couples, but gets an individual almost all the way to their $12,000 threshold. Still though, it takes a sizable income (with the associated income tax deductions) or a big home (with substantial property taxes) to reach the individual threshold; assuming an average state income tax rate of 5% and a 1% property tax rate, reaching the SALT cap still typically requires around a $100,000+/year income and a $500,000+ property, or a $200,000+/year income with no real estate (for those who still rent).

- Big Margin Investing. While mortgage deductions are limited as to the amount of debt principal on which interest can be deducted, investment interest is limited only by the amount of interest and dividends generated by the investments themselves (and that the interest be taxable – no investment interest deductions for municipal bonds). As with the mortgage interest deduction, though, generating “enough” interest requires a substantial amount of debt principal in the first place. On the other hand, since margin interest rates tend to be higher – currently averaging around 8% – it doesn’t take quite as much debt principal… potentially “just” on the order of $150,000 for individuals, or $300,000 for married couples.

- Big Long-Term Care Events. Most medical events are covered by health insurance, and while individuals may still have to pay a (non-trivial) deductible, coverage is usually sufficient to prevent medical expenses alone from triggering the $12,000/$24,000 thresholds, particularly on an ongoing basis. However, long-term care insurance is adopted far less often than health insurance, and tends to have much larger annual expenditures (where semi-private care along averages $225/day or over $80,000/year). Consequently, those who have an ongoing long-term care event often trigger more than enough in annual medical expenses – over and above the 10%-of-AGI threshold – to trigger ongoing itemized deductions.

- Big (IRD-Eligible) Stretch IRAs. One of the largest, and most commonly overlooked, itemized deductions is the IRD (Income in Respect of a Decedent) deduction, which provides beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts (and other inherited pre-tax assets) an income tax deduction for any (Federal) estate taxes that were caused by that IRD asset. Notably, this means the IRD deduction is only available to those who inherit a pre-tax asset like an IRA from someone who actually paid a Federal estate tax (which isn’t many, given the sizable Federal estate tax exemption). Nonetheless, with a top Federal estate tax rate of 40%, those who whom the IRD deduction is available effectively receive an itemized deduction for 40% of their inherited IRA withdrawals… which means inheriting a big IRA from a big estate can trigger a big IRD deduction and therefore ongoing itemized deductions. In practice, though, it will still take a $1M+ IRA for an individual, or a $2M+ IRA for a married couple, to generate enough in IRD deductions to claim ongoing sustained itemized deductions (assuming the stretch IRA faces an annual RMD of only about 3%/year).

Notably, in practice some of the Big 6 are more likely to be relevant in producing ongoing big deductions than others. For instance, sizable mortgages are still fairly common, especially in metropolitan areas where real estate overall remains relatively expensive, and will likely be the most common trigger of sustaining itemized deductions by far. Big charitable contributions – at least, big enough to exceed the Standard Deduction thresholds – are relatively common for high-income individuals as well, but potentially just for the top 5% of households whose income is high enough to sustain such charitable giving (earning $150k+/year), which makes them less common as a trigger overall. Big stretch IRAs, large enough to produce sizable IRD deductions and from someone who paid Federal estate taxes, are even less common, given that only a small portion of 1% of households today face the Federal estate tax in the first place (which means there are very few IRD-eligible inherited IRAs to begin with).

Intermittent Itemized Deductions

While only certain itemized deductions are capable of generating an ongoing sustaining level of deductions enough to exceed the Standard Deduction threshold, a different set of itemized deductions are more likely to create intermittent years where a concentrated burst of deductions allows a taxpayer to itemized that year (but not necessarily the year before or after).

Potential intermittent itemized deductions include:

- Not-Fully-Insured Major Health Events. Even with a high-deductible health insurance plan (to facilitate HSA eligibility), it’s difficult to generate enough medical expenses in a single year to exceed the Standard Deduction, with maximum limits in 2019 of “just” $7,900 for individuals and $15,800 for families… especially since only the excess of those amounts above the 10%-of-AGI limitation would be counted as itemized deductions in the first place. However, not everyone is insured, and sometimes extreme health events can occur that aren’t fully covered by insurance, or have ancillary health-related expenses outside the scope of traditional health insurance coverage. In such years, a major – i.e., $10s of thousands of dollars – health event can create a burst of medical expenses that triggers itemizing.

- Uninsured Hurricane, Wildfire, Or Similar Natural Disasters. In the past, casualty losses could produce a significant deduction, as major events – e.g., a house burning down and not being fully insured – could cause major losses (and create deductions) in the $10s or even $100s of thousands of dollars. Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, though, such casualty losses will only be deductible in the event that they are tied to a Federal disaster area – which most commonly occur with hurricanes, wildfires, or similar wild-scale natural disasters. Of course, ideally such losses – even in the event of a natural disaster – will still be covered by insurance (and to the extent the losses are covered by insurance, they are not deductible because they were reimbursed by insurance). But in the event of a major (Federal-disaster-area) natural disaster, the associated casualty losses (not covered by insurance) may produce at least a sizable single-year itemized loss.

- Big Gambling Losses. In general, gambling losses are treated as personal losses that are not deductible; however, to the extent that an individual has already earned (otherwise taxable) gambling winnings for the year, gambling losses may be claimed as an itemized deduction to offset against the income from those winnings (which must also be reported on the tax return). However, because gambling winnings are reported as (above-the-line) income immediately, and gambling losses are only deductible as itemized deductions, the deduction for gambling losses is sometimes a moot point (as the losses may not be big enough to exceed the Standard Deduction threshold). Nonetheless, when big gambling losses occur – in the same year as big gambling winnings – a major gambling loss can end out being large enough to claim itemized deductions.

- Ponzi Scheme Losses. While theft losses were greatly curtailed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (due to the limitation that it must tie to a Federal disaster area, which is almost impossible to be relevant in the context of theft in particular), theft (and casualty) losses of income-producing property remain deductible (as a miscellaneous itemized deduction). Which includes “theft” losses of investments made into a Ponzi scheme. Notably, the exact timing of when a Ponzi loss actually becomes deductible is dictated by Revenue Ruling 2009-20, as it can take months or even years for the depth of losses (and the certainty of losses) to even be definitively known in order to figure out how much to actually deduct as a Ponzi loss in the first place. Nonetheless, once the deduction for the Ponzi loss is triggered – which under Revenue Ruling 2009-20, may be as early as once the lead figure(s) are indicted for fraud, embezzlement, or a similar crime – a substantial deduction may become available. (With separate rules that apply to determine the taxation of subsequent recovery amounts from the Ponzi scheme that were already previously deducted.)

- Rapid Liquidation Of An (IRD-Eligible) Inherited IRA. As discussed earlier, when an IRA (or other pre-tax asset, like a non-qualified annuity) is inherited from someone who paid Federal estate taxes, a potentially substantial income tax deduction becomes available to the beneficiary (often as large as 40% of the taxable income associated with the pre-tax asset). The IRD deduction is not claimed when the asset is inherited, though; instead, it is claimed as the asset itself is liquidated and taxable income is triggered (with the associated IRD deduction alongside). Thus, when an inherited IRA is stretched out over years, the IRD deduction is stretched out as well; and when an inherited IRA is quickly liquidated, so too are the IRD deductions quickly (and sizably) released. Accordingly, the rapid liquidation of an inherited IRA (that was received from someone who paid Federal estate taxes) can trigger a sizable intermittent itemized deduction in the year(s) of liquidation.

- Big (Or Clumped) Charitable Donations. While sizable ongoing charitable giving can produce sustained charitable deductions, for those who do not give away $10s of thousands of dollars per year, charitable contributions may still become an intermittent itemized deduction when a “big” one-time donation occurs (e.g., making a sizable contribution to the local church or synagogue tied to a major capital campaign). Notably, though, even for those who don’t have plans for a big charitable contribution, it’s feasible to group ongoing contributions into a single-year big contribution by “clumping” charitable contributions with a donor-advised fund. For instance, a household that typically donates $4,000/year might clump together 10 years of donations at once, contribute $40,000 to a donor-advised fund, and then make $4,000/year donations from the DAF to their charities of choice… but by clumping the deductions together, the single-year $40,000 donation allows for at least an intermittent one-year itemized deduction (followed by 9 years where the DAF handles subsequent donations).

For those who do not have sustaining itemized deductions, one of the biggest challenges to deduction planning is that if the Standard Deduction threshold isn’t reached, there is no value to any itemized deductions at all (as they literally don’t add up enough to count). Accordingly, the significance of intermittent itemized deductions is that, in years where they do occur, every other potential itemized deduction becomes far more valuable, because 100% of such additional deductions will actually be deductible (as the Standard Deduction threshold has already been exceeded).

Add-On/Add-Up Deductions

Because itemized deductions produce no tax benefits until they actually add up to more than the Standard Deduction threshold, a wide range of common itemized deductions effectively only create tax value as an “add-on” on top of other larger sustaining or intermittent itemized deductions.

In practice, the most common add-on/add-up deductions are simply the most common versions of various itemized deductions, at levels that simply aren’t large enough to be sustaining itemized deductions. For instance, the interest deductions from a modest mortgage, ongoing property taxes from a modest house, annual state and local income taxes for an average salary, a moderate level of ongoing annual charitable giving, etc.

Of course, the whole point of a (substantially higher) Standard Deduction as a form of tax reform is that it’s easier (and more gracious for tax purposes) to give taxpayers one simple “large” Standard Deduction, rather than putting them through the trouble of adding up a smaller series of ongoing deductions. After all, while itemized deductions that don’t reach the Standard Deduction threshold are “worthless”, they are worthless only because the Standard Deduction has already provided an even-more-generous tax benefit instead.

Example 1. Joseph and Rachel are married and file a joint tax return. Their deductions include $8,000 of mortgage interest, $3,000 of property taxes, $5,000 in state income taxes, and $2,000 in charitable contributions, for a total of $18,000 in itemized deductions. They are wondering what the tax savings would be to donate another $1,000 for a big charity drive they’re involved with.

Unfortunately, though, because the itemized deduction threshold (i.e., the Standard Deduction for married couples) is $24,000, increasing Joseph and Rachel’s deductions from $18,000 (current) to $19,000 (with the additional charitable contribution) produces literally no tax savings at all. Because regardless of the additional charitable donation or not, their deduction will be the same $24,000 Standard Deduction.

On the other hand, a series of small deductions can, in the aggregate, add up to enough, even if no one standalone itemized deduction line item does; but with the substantial increase in the Standard Deduction after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, if often takes a lot of smaller add-up deductions to actually add up to enough.

The key point, though, is simply that the significance of add-on/add-up deductions is that their value varies greatly depending on whether they can, in fact, add up to “enough”, or stack on top of other existing sustaining or intermittent itemized deductions. Accordingly, to the extent that a household can clear the Standard Deduction threshold, it becomes especially valuable to lump other deductions together on top (where, at the margin, they’ll all be valuable). Even and especially if it means pulling deductions forward or delaying them out of years that would not have generated a tax benefit anyway.

Example 2. Joseph and Rachel get a significant raise, and as a result, decide to buy up to a larger house, including both a bigger mortgage, and paying $3,000 in deductible points at closing. Consequently, this year their total deductions will instead be $12,000 in mortgage interest, $4,000 in property taxes, $7,000 in state income taxes, and their $2,000 in charitable contributions, plus the $3,000 in deductible points, bringing their total itemized deductions to $28,000.

Given that their itemized deductions now add up to $28,000 – which exceeds the standard deduction – any additional deductions this year will produce a tax savings (by increasing their itemized deductions over and above the standard deduction). As a result, not only would Joseph and Rachel’s additional donation at the charity drive produce a tax deduction, but the couple might consider a donor-advised fund contribution to “pre-donate” $10,000 of additional charitable giving (for the next 5 years) in the current year when they can fully take advantage of the tax benefits (as next year, when there are no longer deductible mortgage points, they will fall below the Standard Deduction threshold again).

Ultimately, the key point of itemized deduction planning after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is that actually being able to claim itemized deductions is now fairly unique – estimated at no more than about 10% of households per year. For some households, there are sizable enough sustaining itemized deductions to allow for annual tax benefits, while for others itemizing deductions will at best be intermittent and tied to the occasionally large one-off event that triggers a burst of deductions in a single year. While for most households, a slew of common “add-on” deductions won’t produce any actual tax benefit at all… at least, until/unless they can be tacked on top of sustaining deductions or a big intermittent deduction year.

Of course, it’s important to remember that there are still a wide range of so-called “above-the-line” deductions, that are claimed directly against income and not as itemized deductions (which means they’re available regardless of whether they exceed the Standard Deduction at all), from self-employed deductions for retirement plans and health insurance and even self-employment taxes, to contributions to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) and IRA contributions, and even student loan interest.

Nonetheless, for many of the most common deductions that households have historically claimed, from medical expenses to mortgage interest and charitable contributions, actually receiving any tax benefits for those itemized deductions will require more careful planning than ever… or at least a clear understanding of whether or not the household will feasibly be able to itemize deductions at all.