Executive Summary

“Try to ‘live within your means’” is a staple of prudent financial advice – recognizing that not everyone earns the same income (“means”), and therefore not everyone can afford to spend the same. It prescribes that rather than trying to keep up with the Joneses – and their lifestyle spending – you should live within your means, instead.

Yet the challenge is that as income rises, living “within” your means can produce what is, to most other people, an outsized and larger-than-life standard of living. In other words, while it might seem like prudent advice for those who are of struggling means – and therefore, must constrain their spending down to their income means – those who lift their spending up to live within their (much greater) means may be viewed with disdain.

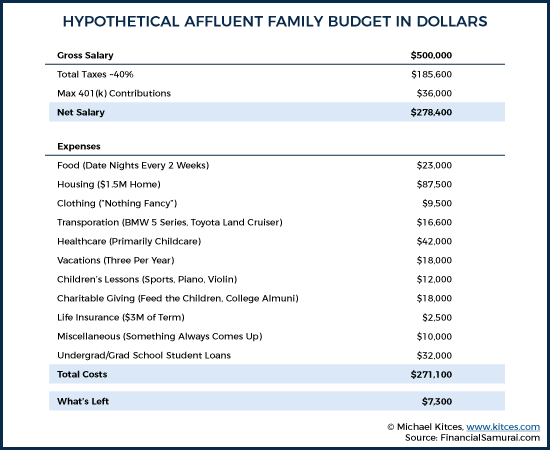

A case-in-point example is a recent article that profiled a high-income young couple with two children living in New York City, who felt that they were living “paycheck to paycheck” on their $500,000/year salary, even as they lived in a $1.5 million home, drove a BMW 5-series and a Toyota Land Cruiser, and took three $6,000/year vacations. Yet relative to their income – in trying to live within their means – the couple was actually spending 40% less on housing that the typical US household, 50% less on food, and 75% less on their cars (high-end though they were). In other words, relative to their means, this affluent couple was arguably doing a better job of “living within their means” than most.

Which raises the question of whether “live within your means” is actually the right advice for anyone – regardless of income – or if the reality is that the strategy breaks down as a prudent spending recommendation at some point. Especially given the research suggesting that there is a “happiness threshold” – beyond about $75,000 of income (and associated spending within its means), more income and spending doesn’t appear to actually improve our emotional well-being.

Of course, some would argue that those who earn might have a “right” to spend more. And that as long as they’re continuing to spend within their means, it remains reasonable and prudent. Nonetheless, the question remains: what does it really mean to “live within your means”, and is there a point where that advice is no longer relevant or prudent?

What Is “Living Within Your Means”?

To “live within your means” simply means to spend less on your lifestyle than you generate in earnings. Your “means” is your income. To live within that threshold, spend less than you earn.

Of course, this is clearly easier said than done, given that the majority of Americans couldn’t even come up with $500 for a surprise expense without putting themselves into debt, at least temporarily. The implication: they’re not living well within their means, and instead are spending right up to (or beyond) their limits, such that there isn’t much of any slack available. Which is the whole point of the saying – to live (well) within your means should mean there’s more than enough left over at the end of the month to deal with a surprise. Or better yet, to actually save for the future.

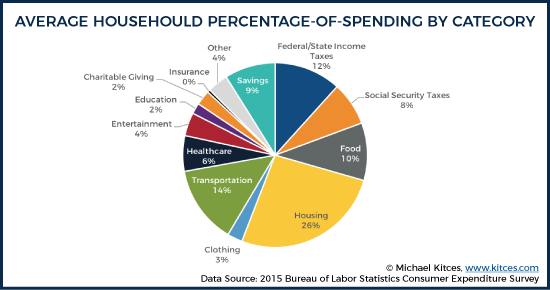

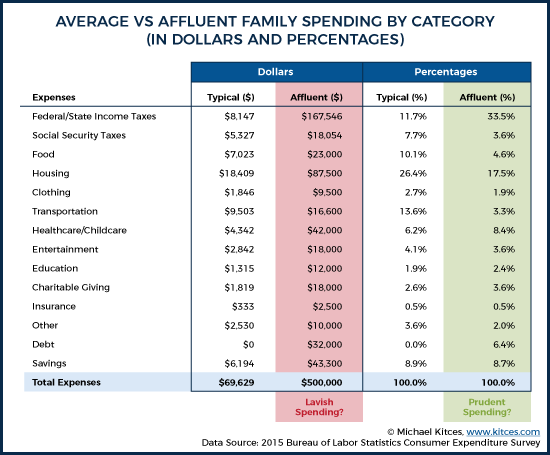

In point of fact, though, the Bureau of Labor Statistics data on Consumer Expenditures – i.e., American household spending – shows that the “typical” household actually does save. The 2015 data, based on an average household income of $69,629 (technically, a “consumer unit”), shows that about 71% of that income goes to spending.

The dominant categories, perhaps not surprisingly, are housing (26%) and transportation (14%), followed by food (10%) and healthcare (6%). Of the other 29% not spent on lifestyle, about 20% goes to Social Security FICA taxes along with Federal and state income taxes, and the remaining 9% or so goes to savings. Which would actually be an annual savings of more than $6,000/year.

In other words, the data suggests that the typical household does actually “live within their means”. Though if much of that saving is tied up in employer-sponsored retirement plans and/or IRAs, it may not be liquid and available if needed. On the one hand, recent research suggests that consumers actually prefer less liquid accounts, as a way to help them save (and ensure they stick with their savings). The bad news, though, is that it can result in a lack of available cash for emergencies (as noted above)!

Of course, while these are “averages”, there’s obviously some variability to them. And for the typical household, a more substantial surprise – a car accident, a roof repair, a major health issue – can be more than enough to cut through the available “savings” cash flow for the year, even if they previously had been “living within their means”. In other words, even if you’re “living within your means” and saving $6,000/year on a $69,629 income, a major health event or accident that costs $10,000 would still be a catastrophe even for the “prudent” family.

In addition, it’s important to recognize that even saving 9% of income may not be enough to reach retirement, as the typical savings guidelines for households is upwards of 15% (whether following household savings guidelines, or Pfau’s “Safe Savings Rate” approach). No wonder, then, that most households seem to feel behind, and may have to rely on the empty nest phase and home stretch leading up to retirement just to play catch-up at the end.

How Affluent Households Live Within Their Means

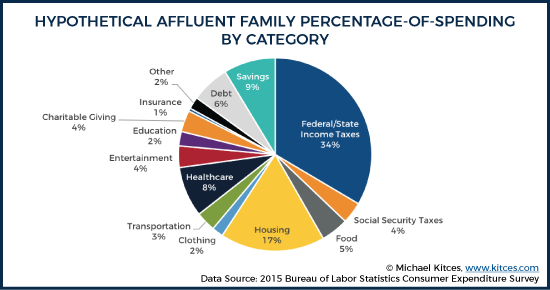

For more affluent households – those well above the $69,629 income of the “typical” household – a challenge emerges: our progressive tax rates means that as income goes up, so too does taxation, which means there’s not as much available to spend in the other categories. In other words, affluent individuals can’t spend as high a percentage of their income on various lifestyle categories as the typical household, and still live within their means.

The good news is that’s often quite manageable, as when income is higher, it doesn’t take as high of a percentage to cover the “essentials” of food, clothing, and housing (and for the modern family, automobiles/transportation). For instance, the average household is spending almost $7,000/year on food (which is almost 10% of their household budget), but an affluent family spending $10,000/year on food (a 40%+ increase) might still only be spending 5% of their income (at a $200,000 salary). Which means even more expensive dining is still a smaller percentage of income.

Thus, for instance, a recent article on Financial Samurai highlighted a hypothetical affluent dual-income 30-something couple in New York City, with two young children, that earns a whopping $500,000/year (they’re both lawyers), yet end up “living paycheck to paycheck” while saving similarly to the “typical” household.

The affluent couple’s household budget is shown below. Not surprising, given how higher tax rates crowd out other spending, their housing costs are “only” 18% of income, food is just 5%, and transportation is only 3%. Though again, at their higher income levels, those percentages still provide more than enough in dollars to afford some very “reasonable” housing, automobiles, and food.

Notably, this affluent household is assumed to also still be paying off some substantial student loan debts (two law school educations isn’t cheap!), and their healthcare expenses are boosted by the cost of childcare for two young children. As a result, it is perhaps no surprise that they feel a bit “constrained” living paycheck to paycheck when more than 40% of their household income is being consumed by taxes and debt payments.

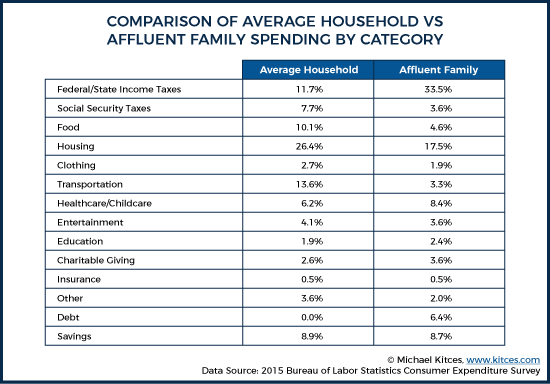

Still, overall, if we compare them to the typical American household, we can see that when it comes to discretionary spending, this affluent couple is spending far less across the board (relative to their income), and has “successfully” adjusted to living within their means. In fact, even their net savings (on a percentage basis) is comparable – though in their case, it actually means maxing out both of their 401(k) plans, and then having a few thousand dollars of (liquid) savings left over.

Should You Evaluate Household Spending On A Dollar Or Percentage Basis?

Notwithstanding this comparison of the affluent couple to the typical household, showing that aside from taxes and a small uptick in entertainment expenses, their household budgetary spending is comparably within their means… it’s notable that the Financial Samurai article generated substantial commentary (nearly 500 comments on the article), huge media buzz, and no small amount of outraged discussion on Twitter. Because in the original article, the expenses weren’t shown on a percentage basis, but on a dollar basis.

And when broken out on a dollar basis, the affluent couple’s spending was as follows:

When viewed in absolute dollar amounts of spending, it is not difficult to see, for the typical household, where the relative frustration would come from. This affluent couple, who are ‘struggling’ to just barely live within their means, owns two relatively high-end cars, and a $1.5M home. They spend $42,000 on child care. They take not just a $6,000 vacation, but three $6,000 vacations per year. And they’re dropping $1,000 per month on their kids’ sports and music lessons (on top of child care expenses). Not to mention that they’re giving away to charity almost triple what the average household saves in an entire year.

Accordingly, “suggestions” on how the couple could feel more in control of their household spending just poured in:

“No one needs a $1.5M house! Have you ever heard of renting?”

“No one ‘needs’ a 5-series BMW!”

“If you’re feeling poor, don’t give so much away.”

“Don’t put so much into your kids that you can’t afford your own retirement!

The criticism was in high volume. Yet, as noted earlier, relative to their income, this affluent household spends substantially less than the average American. In fact, they spend less in every category except when it comes to care for their children – which is both known to be extremely expense in New York City, and is arguably a question of family values as much as fiscal responsibility (as in many families and cultures, it’s long been a priority to spend on their children over themselves).

The core problem, of course, is that most of the critics were comparing this high-income couple’s spending to their own income, rather than the couple’s income. Which makes expenses that might seem “reasonable” relative to a high income, as absurd extravagances to outside critics. Even though that highly criticized 5-Series BMW is still leading the couple to spend only half the percentage of their income on transportation as the typical American.

The Happiness Threshold And Living Within Your Means

Ultimately, all of this raises very interesting questions about what it really means to live within your means, and what “prudent” spending really is.

In theory, this couple should have been celebrated, for adjusting their spending around the fact that taxes (and student loan debt) are chewing up almost triple the percentage of their income of the typical household. In turn, they adjusted by allocating half the budget to food, 1/4th the budget to transportation, and 40% less budget to housing, while keeping the rest of their expenses in-line or lower than the typical household as well. Yet in practice, they were lambasted, because the dollar amount of their spending seemed so lavish compared to others.

But which, actually, is the better point of comparison? On the one hand, the whole point of living within your means, suggests that your spending should be compared to your means (i.e., your income). Which means this couple is spending prudently within their means (at least, as much as any other typical household). Granted, they may not be on track for retirement, but neither is any household saving “only” 9% of their income. Which, actually, is most of them. And in point of fact, this affluent couple may actually be well on track – even if they don’t feel like it now, with less than 2% of their income left over at the end of the year – given that they will have more income to save during the empty nest phase when those child expenses fall away, and eventually the student loan debt burden will alleviate once it’s paid off as well. In other words, if they can just stick with this budget, where their personal consumption is barely 50% of their income, they’re actually well on track.

Yet the interesting caveat to this is that at least some research suggests our happiness (i.e., emotional well-being) doesn’t materially increase as our income (and associated spending) rises above $75,000/year. Which means the couple with $500,000 of income, even if they’re “just” spending 50% of that – or about $250,000/year – is still far past the point of getting much additional happiness from their spending dollars. In other words, maybe it is more appropriate to view their budget as excessive, relative to the “happiness threshold” where more income and spending isn’t associated with more happiness. Even if we gross up their $75,000 spending target a bit for their high cost-of-living area (they are in New York City), they’re still spending way, way beyond the happiness threshold. Not to mention well beyond most other people’s happiness threshold… which perhaps helps to explain where the anger comes from.

Thus, the question arises: is “live within your means” even the right way to evaluate prudent spending in the first place, recognizing what happens to living expenses as the means (income) rises? Is it a high-income couple’s “right” to spend far more than others, if they’ve managed to earn far more than others, and make their own decision about whether the spending is meaningful to them (or not)? Or is “don’t spend beyond the happiness threshold” a better way to evaluate spending, particularly for those whose incomes carry them well beyond that threshold? Is this affluent couple a model of prudence, living well within their means, and being well on track for retirement (even if their income feels “tight’ right now)? Or is it really outrageous to spend this much when the average household spends so much less, and the couple is being “irresponsible” because they’ve chosen to lift their lifestyle to be within their means instead of getting even further along towards retirement, given that their spending is so far beyond the happiness threshold (and what most other people can afford to enjoy)?

Ultimately, the key point is to recognize that the standard recommendation to “live within your means” automatically scales to your means; it implies that those who are more affluent can and “should” be able to spend more. Yet when an affluent household does spend more, it is highly criticized, both on comparative terms, and in questioning whether that higher spending is even generating a real “return” on happiness and emotional well-being. And so, is it time to ditch the advice to “live within your means”, and instead talk about prudent spending in the absolute dollar terms of what it takes, according to the empirical research, to really optimize happiness and emotional well-being?

So what do you think? Is “live within your means” prudent guidance at all income levels? Or is there a point where it breaks down? Is the $75,000/year happiness threshold a better way to evaluate responsible spending? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Interesting take on what we’re really saying when we advise people to “live within their means”. I would argue this is simply a starting point and more relevant to those with average or lower incomes. After all, it means spending less than you make, which is the only way to get wealthy and that is what most people struggle with.

But since happiness is the point for most people, it makes sense to guide those with higher incomes to spend only to the point of high (maybe not quite maximum) happiness, and save the rest to reach financial independence earlier in life. This seems like it’d be the best personal outcome vs being able to spend more but “within their means” since it’s clear this spending doesn’t provide a significant boost to happiness.

This affluent couple example highlights this. They are clearly unhappy with their financial situation despite a very high dollar spending. It seems they would be better off (i.e. happier) by saving a lot more than a “within their means” calculation would indicate. They’d be less financially frustrated and would adjust to a lower level of spending, based on the research of spending vs happiness.

So “live within your means” is a good starting point, but helping those with more “means” focus on a happiness-focused spending level while saving more, seems like a more enlightened advisor approach.

Important topic, thanks for tackling it Michael. I’m firmly on the side of “just because you make it, you don’t have to spend it to be happy.” My own writing about financial independence demonstrates how that philosophy works out in a real life. Routine lifestyle inflation as people make more money in their careers is unhealthy for the planet, and often for the people themselves. Same principle when buying a home: Just because you can “afford more” doesn’t mean you should own it, or that it will make you happy. Financial advisors can make a positive contribution to the world and their clients’ lives by bringing these principles to mind. Thanks again.

Based on Michael’s charts, an easy financial planning approach may be, no matter which of the two groups you’re in, to pay yourself first, say 10% into savings. And then figure out how to live on or donate the rest.

I submit that 10% to savings, 10% to charity (others) and 80% for living expenses/taxes/debt forms a good starting point for most families with the possibility of increasing the dollar and percentages for savings and charity as the overall income level increases or the debt level decreases.

I like that approach. It certainly beats detailed budgeting.

This is Ramit Sethi’s approach. I use it for myself and my clients. It works, plain and simple. Budgeting never did for me – I hate the exercise, and it’s laden with guilt and constant decisions.

http://tim.blog/2009/03/26/the-psychology-of-automation-building-a-bulletproof-personal-finance-system/

I look at this a different way. My clients are all high earners, and all in the process of saving for specific goals. As long as they are able to fund the goals that they have (college funding, new house, retirement, etc), and can cash flow expenses, I tell them they can spend whatever they want. For many, they are working to afford some quality of life. Why penalize them by pigeon holing them into some sort of industry metric? Or shame them for their success? Quality of life is personal and subjective. Our job as advisors and financial planners is to help our clients live the quality of life they are working hard to achieve, and to guide them along their life to reach their personal goals.

I agree with Bridget’s comments.

I would also add that the “happiness threshold” for our family was well in excess of $75,000 or $90,000. I’d put it more in the $250,000 gross salary range. Once my income increased above that level, I was able to save most of the excess (and save I did, as I was able to early retire at 53 without a pension).

Michael, that’s 75k in 2009 dollars. More like 90k now.

And of course that’s an average. It has to be further adjusted for geography and life circumstances.

Taxes are not optional, they’re mandatory, so there’s no including them in the “means”. “Living within the means” means a lifestyle that is compatible with disposable income.

This article is utterly and completely confusing. All of the percentages and the discussion should be based on disposable income, not on something that does not equate to means (gross income).

This all reminded me of Dan Price/Gravity Payments. Remember when he made $70k the minimum wage at his company because he read the studies that show people feel financially secure at that level? His lower-earning staff were very pleased. His higher earners were most emphatically NOT pleased; I believe a few of them left the company.

So, this makes me ask the question: Is the ‘happiness’ derived by this income level because people can SPEND this much? Or is it because they feel better about themselves (and life in general) because they are EARNING this much? At $75k earnings in a time when $69k is average, perhaps that is just enough of a premium to make workers feel proud of their earnings… which at this point makes them Above Average.

Back to Dan Price and his high-earners that quit. They quit because they felt their contributions to the company were devalued by giving everyone the ‘happiness’ raise. Their level of income didn’t feel good to them anymore because it had lost its power of comparison.

That is not enough liquid savings for that level of expenses.

Michael et al,

Recommend reading “The Richest Man in Babylon” by George S. Clason. It’s not just about living within your means, it’s about paying yourself first. From the beginning of wage earnings, not when you think you can afford it, because that may be never or at best too late. If you don’t have a guaranteed pension 8 or 9% savings is not enough, should be at least 15%, maybe 20%. I have no problem with anyone enjoying living but a big problem with those who spend their future for a good time today.

Scott

Realistically, for most families to simultaneously accomplish all the basic objectives we counsel them on the income required is more like 2x the ‘happiness’ income level. In high cost areas, more like $200-$250k. Earning well above those levels presents a quandry – be content to ‘live within my means’ or make the rat race completely optional well short of retirement age. Essentially, building assets such that work is optional IS the ultimate freedom. As long as there’s not a crushing debt burden, how one spends, once they have the assets to sustain a lifestyle at around 2x the median household income level, is fairly irrelevant.

Hi Michael, important discussion. I think the ‘happiness threshold’ article was making the case that after some income level, higher earning doesn’t increase emotional well-being or happiness. Although, the article concluded that life satisfaction did increase with higher incomes. I’m not sure we could easily find consensus on the difference between emotional well-being, life satisfaction and happiness (or that we should try). The point being, as I saw it, not having enough money causes unhappiness.

For me, raising the discussion of what constitutes ‘living within your means’ is the bigger conversation here. Generally speaking, I believe it has come to mean spending less than you earn and not sinking into increased debt. Not a terribly high bar and certainly not a plan for a financially stable life.

I am a real estate Broker in California and see the routine process for determining ‘how much you can afford’ as asking the bank how much you can borrow. That’s something like asking the car salesman how much you should spend on a new car.

Most people don’t know what ‘living within their means’ really… well, means. We need to get home buyers talking to financial planners before they buy a house. A poor home choice and budget, in any income category, will preclude a lot of options for many years to come.

Nice message.

It’s an interesting topic, but I suspect it won’t get any long-term traction because we’re ultimately dealing with envy and class warfare here which “Progressive” policies try to take care of. High income earners choose to prioritize their social signaling over happiness, so we’re not going to be too sympathetic to their complaining of “financial tightness” when they’re outlier spending on a high falutin’ lifestyle that 95% of other people can only dream of because they weren’t lucky enough to be breeded into the optimal social, economic and financial circumstances. Cry me a bloody river. So a story about how high income earners actually prioritize happiness, downsize radically and give up the superficial social signaling would carry lot more weight; so would a story on a Horatio-style rags to riches struggle. We’re just not sympathetic to people complaining who had most everything handed to them. The shocking thing is these people are in such an unreality bubble they don’t even realize it.

I don’t buy the validity of a flat $75K threshold regardless of geography. $75K in Nebraska or Mississippi buys a much different quality of life than it does in New York, San Francisco or Washington, DC. Seems to me at a minimum this number needs to be indexed to local cost of living.

Making judgments about what is necessary for anyone else’s happiness feels far beyond the realm of financial planning to me. But, prescribing a level of savings that imposes a spending cap and builds capital for the future is necessary and reasonable if a clients’ future goals include retiring or living on less than they currently earn. Rather than telling clients how to spend their money, we focus on showing them how much they can spend now and still hope to achieve their goals for the future. Once they see the numbers, they generally know where they are spending a lot and what items need to be cut or at least reconsidered.