Executive Summary

For financial advisors who pride ourselves on the quality of the advice we provide to clients, it can sometimes be easy to lose sight of the importance of the more physical elements of our business that seem qualitatively irrelevant to the value of the guidance and recommendations we give to clients. However, as a tremendous amount of psychological research suggests, we should be careful not to overlook the more "theatrical" elements of a financial planning meeting – from the clothes we wear and the way we present information to clients, to the design and set up of our office – as the "theater" of financial planning actually does influence our clients, and their ability to implement our advice in a meaningful manner.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – examines why it is important to both acknowledge and manage the theater of financial planning, particularly given the ways in which clients and prospective clients utilize the signals we as advisors send (both consciously and unconsciously) to decide everything from whom to hire, to what financial recommendations they should implement (or not!).

It is widely acknowledged that effective communication is an important aspect of what financial advisors do. However, something that is less commonly appreciated is the role that our environment plays in facilitating that communication. In his book, Suggestible You, Erik Vance examines the ways in which our suggestible minds are influenced by the stories we hear and the environments we hear those stories in. In particular, Vance examines the "theater of medicine", and its surprisingly powerful role in shaping the perceptions and beliefs of patients, which can, in turn, influence their physical health and well-being as well!

Additionally, the physical spaces we occupy (such as our office) can actually say a lot about us. Though laboratory research in financial planning is still very young, and scholars are only beginning to delve into how the offices of financial advisors can optimally be designed, some research from other fields has found that our physical environments can actually say even more about our personalities than some commonly used tools and assessments. At the heart of this are ways in which our personality manifests in certain behaviors which leave physical evidence within our environments that is really hard to fake – from mementos we collect and things intentionally place out for others to see, to more subtle clues such as the way we dress and organize things on our desk.

Ultimately, financial advisors have many options for trying to better manage the theater of financial planning... from sending signals of our conscientiousness through our clothing (e.g., formal dress) and communication style (e.g., controlled posture and calm speech), to signals of our competence through education and professional designations (e.g., CFP certification), and even signaling our knowledge of and solidarity with niche communities that we service... there are many ways in which we can seek to manage the "theater" of our financial planning to help our clients adopt and implement wise financial planning practices!

Acknowledging The “Theater” Of Financial Planning

Sometimes financial advisors—and particularly those of us who may be most interested in the technically-oriented side of financial planning—can be quick to write-off the “theater” of financial planning. After all, if we can serve our clients well and give them really good advice (far better than that slick salesman down the street, no doubt!), then why worry about the suit we wear, the car we drive, or the aesthetic of our office? These factors are all superficial and do not influence the actual quality of the advice we deliver to clients – which is what our clients are paying us for, isn’t it?

However, psychological research gives us good reason to question just how superficial the actual “theater” of financial planning is. From the costumes we wear, to the props we use, and even the way we arrange our financial planning “stage”… the performances we put on can and do influence our clients – including the emotions they feel, the perceptions they form, and the eventual decisions they make.

As a result, those of us who truly do want to help our clients make the best possible decisions should not ignore both the conscious and unconscious influences of financial planning theater.

Our Highly Suggestible Minds

In his 2016 book, Suggestible You, Erik Vance examines the science behind our highly suggestible minds, and finds that at all sorts of human behaviors that seem to have no scientific basis—from voodoo and shamanism, to magic healing crystals and miracle vitamin pills—surprisingly seem to actually have some real-world effects.

What’s most interesting about Vance’s approach, is that rather than just write these things off as mere pseudoscience, Vance examines whether there could be other mechanisms that might help explain why such behaviors could have effects, even though the actual treatments themselves are not scientifically supported. And in his investigation, Vance identifies a potential explanation: the power of our highly suggestible minds.

Vance explores a wide range of case studies and scientific literature which suggests that not only do our experiences influence our perceptions and beliefs, but that our experiences alone can actually improve our health and well-being. In other words, it’s not just that our minds are capable of making us think we are better when we are not, but that our brains can actually enhance (or worsen) our physical and mental well-being.

At the heart of this powerful phenomena is storytelling—which has a long history of being deeply integrated into healing and medicine. In particular, storytelling is powerful in influencing our beliefs and expectations, which researchers have been discovering are far more powerful than we realized.

For instance, most people are familiar with the concept of a placebo effect: A participant in a study receives a sham treatment (e.g., a sugar pill) and yet experiences positive medical effects which cannot be attributed to the sugar pill itself. But only recently have medical researchers begun to really gain a better understanding of how these complex effects work.

At first, researchers were naturally skeptical of what placebos actually were. Many felt placebos were likely just a form of response bias (e.g., participants were trying to provide responses researchers wanted to hear), confirmation bias (e.g., researchers were seeing the effects they wanted to see), or publication bias (e.g., studies with interesting findings get published even though the results were just the result of chance). But the research so far suggests that, at least for some placebos, the science behind them is actually much more interesting.

For instance, Vance notes a 2004 fMRI study that provided some of the first evidence of how our brains can actually self-medicate against pain by engaging our “internal pharmacy”—i.e., neurotransmitters and hormones such as opioids, dopamine, and endocannabinoids, which our brains can release to self-medicate ourselves. In summarizing the findings of the 2004 fMRI study in which participants were conditioned to believe a non-pain relieving cream could actually relieve the pain of an electric shock, Vance writes (emphasis mine):

The most interesting part was what the brain scans showed. Normal pain sensations begin at an injury and travel in a split second up through the spine to a network of brain areas that recognize the sensation as pain. A placebo response travels in the opposite direction, beginning in the brain. An expectation of healing in the prefrontal cortex sends signals to parts of the brain stem, which creates opioids and releases them down to the spinal cord. We don’t imagine we’re not in pain. We self-medicate, literally, by expecting the relief we’ve been conditioned to receive.

In other words, it’s not just that placebos can make us think we are feeling better, but that the right experiences and expectations can actually cause our minds to induce a genuine healing process, independent of any actual medical treatment provided. And the placebo effect works at least in part because our expectation that it will work literally triggers our own internal neurochemistry to help make it so.

Staging The Theater Of Medicine (And Financial Planning)

In addition to actually being a good storyteller in the first place (financial advisors may want to note Scott West and Mitch Anthony’s book, Storyselling for Financial Advisors), another key element of storytelling is the broader “theater” in which that storytelling takes place, which can ultimately have the effect of diminishing or enhancing the power and believability of a story being told. Which is important, as ultimately it is our genuine beliefs and expectations which influence the surprisingly good (or bad!) outcomes which Vance examines.

Given Vance’s book’s focus on the physical healing process, he places a particular emphasis on the ways in which the “theater of medicine” has been found to influence our health. Simply put, the theater of medicine refers to the many factors of the environment around us which all tell our brains that it is time to get better when we enter a medical facility. From the uniforms that people wear (e.g., the authority invoked by an EMT’s uniform, the sterility invoked by crisp and clean nurse’s scrubs, and the expertise invoked by a doctor’s white lab coat), to the props that are used (e.g., stethoscope, thermometers, and other medical equipment), and even the general arrangement of a medical “stage” around us (e.g., anatomical charts, the scent of disinfectant, and degrees and other credentials prominently displayed), we are constantly reminded that it is time to get better.

Of course, these elements all serve a genuine purpose as well, but the reality is that at a well-staged medical environment can actually make a physician more effective. In most modern medical facilities, we both consciously and unconsciously receive the message that we are in a safe environment and being taken care of by qualified professionals. Certainly doctors could stage their “performance” much differently—perhaps ditching the formality of the white lab coat, storing equipment in a manner that is much less conspicuous, or eliminating the anatomical charts (which I assume are almost never actually referenced)—but this would likely be counterproductive, as it may impair the way that patients experience the medical environment.

In a medical context, theater and storytelling can be really powerful tools (though, admittedly, for both good and bad). In a famous 1955 paper in The Journal of the American Medical Association, Henry Beecher noted:

Placebos have doubtless been used for centuries by wise physicians as well as by quacks, but it is only recently that recognition of an enquiring kind has been given the clinical circumstance where the use of this tool is essential.

Beecher goes on to suggest that as many as 30% of patients will have placebo responses to a particular drug. However, Vance notes that subsequent estimates have been even higher (as high as 80% - 100%), particularly for ailments that are highly susceptible to placebo responses, such as pain and depression.

Placebos themselves may be more or less prevalent based on how they are presented. For instance, place responses are more common when the pills used are larger, made of certain colors, or are more expensive. Fascinatingly, placebos effects—supported by the broader theater in which makes such effects are possible—can even occur when people have been told they are taking a placebo! Of course, as financial advisors, we don’t prescribe drugs to our clients or address their physical health, but the key point is that is that if our minds (both consciously and unconsciously) are so heavily influenced by belief and perception that we can literally self-medicate ourselves, it would be unlikely that storytelling (and theater in which those stories are told) wasn’t highly important in a financial context as well.

The Surprising Details Our Office Can Reveal About Us

Though laboratory research in financial planning is still very young and scholars are only beginning to delve into how the offices of financial advisors can optimally be designed, we can look to other fields for insights to consider when designing a financial advisor’s office to invoke similar “theater” effects that may help clients put themselves into the frame of mind that they’re about to change their financial behaviors for the better.

One such line of research comes from Sam Gosling, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. In his book, Snoop, Gosling examines what our physical spaces—including our offices—can reveal about us.

Gosling’s field research, which involved “snooping” in the actual bedrooms and offices of research participants to see what he and his colleagues could determine about the individuals who occupy those spaces, found that our physical environments actually reveal a lot about our personality. In fact, Gosling and his colleagues found that sometimes our physical environments say even more about us than tools such as self-assessments. The reason for this is that while we might bias a self-assessment in a direction that we aspire towards or think others will be more approving of, our physical environment includes many unconscious manifestations of our personality in our everyday life.

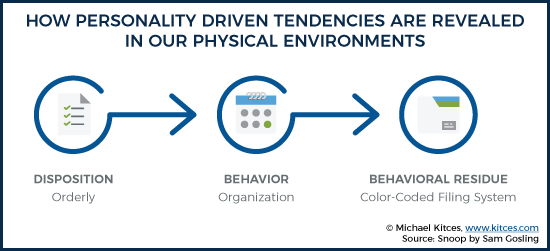

Gosling refers to these manifestations as “behavioral residue”, as it is quite literally the evidence that accumulates based on our personality-driven tendencies to engage (or not) in certain behaviors. This type of evidence can be particularly revealing, as it is often the hardest to fake.

In a 2002 paper in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Gosling and his coauthors identify four specific mechanisms through which such behavioral residue can emerge: self-directed identity claims (things we display for ourselves), other-directed identity claims (things we display for others), interior behavioral residue (residue which accumulates based on behavior inside or homes and offices), and exterior behavioral residue (residue which accumulates as the result of behavior that we engage in outside of our homes and offices).

In each case, an individual possesses some underlying personality-driven disposition, which leads to a particular behavior, which then leaves some evidence of that behavior. For instance, a financial advisor may be sentimental (personality-driven disposition), which leads them to collect memorabilia (behavior), and that results in an old baseball that sits amongst some other items on their bookshelf (behavioral residue). Or a financial advisor may be sensation-seeking (personality-driven disposition), which leads them to drive a motorcycle (behavior), which results in them needing to carry a motorcycle helmet around with them (behavioral residue).

Of course, the reality is that behavior (and its resulting residue) can be highly nuanced, which can lead to a lack of clarity regarding what some behavioral residue actually says about an individual. For instance, an advisor may have a baseball in their office as a way to signal that the advisor likes to watch baseball (an other-directed identity claim which could encourage a prospect or client to start a conversation on a topic of mutual interest), as a piece of memorabilia solely with personal significance (a self-directed identity claim which may help regulate an advisor’s emotions or motivation), or simply because a colleague dropped the ball on their way out of the office and the advisor is holding onto it until it can be returned to its owner (a form of residue which, at best, just tells us a bit about the advisor’s personality). But as an outsider looking in, it isn’t immediately clear why the baseball is in the environment.

However, we may sometimes be able to gain some clues from how things in an environment are positioned. Gosling notes that there are some interesting differences between self-directed and other-directed identity claims. Because the intended audience of self-directed and other-directed identity claims are different, individuals will tend to position such claims differently within their office. For instance, other-directed identity claims would be more visible from places where clients would sit (since clients are the intended audience), whereas self-directed identity claims may be more (or even exclusively) visible from an advisor’s perspective.

As a result, when trying to learn about an individual by viewing their office, it is helpful to view the office from multiple perspectives. While an office may look neat and tidy from the client’s chair (an example of behavioral residue which would indicate high conscientiousness), the pile of papers and an overflowing waste bin hurriedly stashed out of the client’s sight may tell a different story.

But the reality simply is that what we display in our physical spaces (both intentionally and unintentionally) can say a lot about us. Which means it’s important to carefully consider what our environment is saying about us, and whether that aligns with the message we intend (or desire) to convey!

How We Can Better Manage The Theater Of Financial Planning

When it comes to better managing the “theater” of financial planning, the first thing to do is acknowledge that it exists.

Again, particularly for those of us who are most strongly drawn to the technical side of financial planning, this can be a challenge. While the quality of our services does matter, our ability to communicate our findings to clients (storytelling) and the broader environment in which we do that storytelling (theater) may matter just as much, if not more, than our technical skills. And this may be particularly true when it comes to influencing whether our clients actually follow-through and implement the strategies we recommend.

Sending Signals That Are Genuine

Depending on a particular advisor’s office arrangements, they may have more or less control over how an office is set up, but there are always ways in which we can craft our environment to send better or worse signals to others.

At the most obvious level, are the signals that we intend to send to clients. While many of these signals will be common to many advisory firm offices—signaling characteristics such as competence, professionalism, trustworthiness, etc.—they are still important boxes to check. Though the doctor who wears a lab coat isn’t “unique”, the doctor who doesn’t may not put his or her clients in the best frame of mind to increase the client’s odds of healing. In the context of advisory firms, awards or degrees displayed around an office, the magazines available to customers in the reception area, and the way we dress, are all signals to consumers who have relatively little information use when assessing our intangible services.

Ideally, we are signaling information that aligns with our true goals, skills, interests, values, and personality to others. For instance, if an advisor takes pride in their professional accomplishment and proudly displays a credential worthy of admiration, Gosling notes that their inner and outer selves would be in alignment.

However, our inner and outer selves are not always aligned. In particular, our environment also contains “deceptions” that we may sometimes use to try and mask our actual traits. For instance, most people would generally like to be thought of as organized, as it’s a trait that is generally respected and rewarded in our society. As a result, regardless of how truly organized we are, most people will try and tidy up to at least give the impression they are organized. But, unfortunately for those of us who may not be naturally inclined to alphabetize bookshelves, deceptions are often fairly easy to spot. Of course, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t still try our best to be organized, but we should be careful how we portray ourselves to others, because claiming to be organized when we are not is likely to perceived worse than being just being genuine selves.

Unfortunately, when it comes to areas where consumers lack the information needed to provide a meaningful assessment (e.g., assessing the quality of investment recommendations), deception can be harder to detect. Consider the famous CFP Board commercial in which a DJ was transformed into a financial advisor who appeared to come off as reputable to consumers based on how he was dressed and the professionalism of his (staged) office setting. The “experiment” was set up in a manner which took advantage of the “theater” of financial planning. Illustrating that since most consumers aren’t financial advisors themselves, they struggle to assess the true quality of a financial advisor. As a result, by simply being confident, looking the part, and using some industry buzzwords (e.g., asset allocation, 401k, etc.) the DJ was able to come off as knowledgeable and trustworthy.

Had the CFP Board put the same DJ in a rundown office, dressed casually, and had him perform without confidence, it’s doubtful consumers would have had the same response. In fact, you could likely put a highly qualified advisor delivering excellent advice in the same rundown/casual setting and consumers would still doubt whether the advisor was knowledgeable, because they can’t actually assess competence in the first place, though the wide range of contextual clues they can assess would be indicating something was not right. (This is also why credentials like the CFP marks help, as it provides a meaningful signal of competence in an area where consumers would struggle to make that assessment themselves. Because, as the DJ commercial notes, anyone can put on a suit and tie, but not everyone can get the CFP marks!)

Of course, financial advisors should never fake credentials or expertise that they do not have for both ethical and legal reasons, but the point remains that the “theater” of financial planning is so powerful, that it can even mask otherwise unqualified individuals. Which means it is crucial for those who are competent and ethical to leverage all the tools at their disposal!

What Financial Advisors Signal With Their Clothing

Gosling uses the terms “seepage” or “leakage” to refer to behavioral cues about our personality (positive or negative) that are revealed without our being aware of them. One particularly powerful way in which this can happen is through our clothing.

For instance, conscientiousness is one of the personality traits that is often found to be the most desirable in a professional context. Based on the findings of some prior studies, Gosling put together a “Snooping Field Guide” which includes both the items that snoopers most often used to assess a particular personality trait, as well as the items that were found to actually predict those traits best. In both cases, formal dress was found to be the strongest indicator of conscientiousness.

As a result, this is one more reason advisors may want to be very careful before dressing down. Particularly when we don’t like to dress up, we’re likely to engage in all sorts of motivated reasoning to convince ourselves it is okay to dress down. However, the formality of our clothing is perhaps the single greatest visual signal of high conscientiousness that we can send.

In terms of other clothing-related traits that have been found in prior research, observers have previously relied on:

- Fashionable dress as an indicator of openness

- Make-up as an indicator of openness and extraversion

- Showy dress as an indicator of extraversion

- Non-showy dress as an indicator of conscientiousness

Notably, past research indicated these weren’t actually reliable indicators, but the key point here is that those evaluating the personalities of others thought they were. Interestingly, dark clothing was an indicator of neuroticism, though it was not picked up on by those doing the evaluations (it was identified by researchers evaluating data after the fact).

What Financial Advisors Signal With Their Communication Style

Not only does the way we communicate affect the quality of our storytelling, but it is also a way in which people tend to try and pick up clues about the personalities of others.

Again noting that conscientiousness is among the most desirable traits when making hiring decisions in a professional context, advisors may want to be aware that the following were used by reviewers to assess one’s level of conscientiousness:

- Controlled sitting posture

- Touches one’s own body infrequently

- Fluent speech

- Calm speech

- Easy to understand

Notably, again, these weren’t actually found to be meaningful predictors of conscientiousness, but they were cues that people relied on when making assessments. In other words, right or wrong, those who exhibit these queues may be more likely to be perceived as conscientious, which can make a difference when prospects are interviewing prospective financial advisors.

While we don’t know enough about what clients look for in an advisor to have much confidence in how one might signal other traits (and preferences likely vary based on a client’s own personality), some other notable indicators included (*indicates cues that were actually found to be predictive of the underlying personality traits):

- Openness: friendly expression, self-assured expression, extensive smiling, pleasant voice, fluent speech, easy to understand, and calm speaking

- Extraversion: Friendly expression*, self-assured expression*, extensive smiling*, relaxed walking*, swings arms when walking*, loud and powerful voice*

- Agreeableness: Friendly expression*, extensive smiling, pleasant voice

- Neuroticism: Grumpy expression, timid expression, little smiling, lack of arm swinging when walking, stiffness when walking, weak voice, unpleasant voice, halting speech, difficult to understand, hectic speech

Financial Advisor Signals of Competence

As discussed above, signaling competence is particularly tricky since the prospect or client is presumably less knowledgeable than the financial advisor. Which means, ironically, most consumers don’t even know how to determine whether a financial advisor is competent or not, and aren’t even able to judge the quality of their answers to demonstrate competency. Which means it becomes all the more important to properly “signal” competence by any means possible (especially for those who really are competent!).

The first is through professional designations. When consumers believe that a designation is credible (and unfortunately, it’s the belief here that actually matters), the credibility of the designation conveys credibility to the advisor who has it. Which means the CFP may be meaningless to a consumer who is unaware of the CFP or under the impression it is not a meaningful designation, whereas a meaningless designation can sway a consumer if they believe it sounds important. Fortunately, the CFP marks have become a more credible signal as consumer awareness continues to rise with the CFP Board’s public awareness campaign.

A more general way in which we signal competence/intelligence is often through college degrees. While economists continue to debate over whether college actually makes us any smarter, it is at least generally accepted that, all else equal, more intelligence makes it easier to get into more prestigious schools, and that college itself serves as a means for individuals to signal some combination of intelligence and work ethic. Given that most people know it is very hard to get into Harvard and earn a Ph.D., there is a major competency signal conveyed by having a Ph.D. from Harvard. Of course, it’s entirely possible to have a Ph.D. from Harvard and still be clueless about financial planning. But for a consumer trying to find some meaningful signal of competence, “he/she was smart enough to get a Ph.D. from Harvard” is better than nothing.

As a result, advisors may want to think carefully about how they display professional credentials and degrees in their office. This doesn’t mean such signals need to be in front of clients at all times (nor does it mean advisors need to go out and acquire advanced degrees, as there is certainly considerable diminishing marginal returns in highly personal business like financial planning), but much like the theater of medicine is often elevated by having a doctor’s credentials visible, financial advisors may want to do the same.

Signaling Like Everyone Else

As boring as it may sound, there’s a certain degree of “fitting in” that is likely helpful in managing the theater of financial planning.

While it would be nice to have some actual research to back it up, there are likely some items clients just generally associate with “finance” that would be helpful for setting the stage of financial planning. Items like tickers, charts, spreadsheets, and maybe even CNBC running in the background could be items which fall into this category.

The irony, of course, is that many advisors like to steer their clients away from CNBC and a lot of these financially-related items. Nonetheless, to the extent that clients might subconsciously associate them with the theater of financial planning, hiding them from clients could actually make the advisor seem less credible. Which means that while advisors may not want to place such TVs in a waiting room where clients would actually watch it, a strategically positioned TV a client might see walking back to an advisor’s office could still help set the stage (without encouraging the potentially harmful client behavior). If anything, it may help to convey “we keep an eye on CNBC, so you don’t have to!”

Beyond those types of props, there is the general professional nature of an office. The idea here is to (accurately) create the sense that the client is here to talk about something important with a qualified professional. What that means likely varies a lot from one market and target clientele to another, but, to the extent possible, advisors should probably strive to ensure they at least match the general quality of offices that clients may be meeting with competitors in. Because while having a professional-looking office like everyone else may not ensure you get the prospective client, not having an office on par with competitors could genuinely lose the prospect.

Signaling A Niche

Perhaps the most effective way to “customize” an advisor’s office is to signal to a niche. Whereas the hope for much of the setting is that it invokes the theater of financial planning without actually drawing overt attention, when signaling to a niche, advisors should be looking for key “other-directed” identity claims they can send.

Of course, these specific signals will vary based on an advisor’s target niche, but the key is to be able to send some type of signal that displays a commonality that the client is unlikely to find with other advisors (at least in their immediate market).

Additionally, as a general principle, the more “costly” a signal is to send, the more meaningful it will be to those who receive it. This could mean something like cost in terms of time (e.g., a photo/award/etc. associated with donating considerable time to a nonprofit of shared interest versus a mug with the nonprofit’s logo on it). Or, while riskier, it could also be a cost in terms of signaling a shared identity that would actually be harmful for an advisor to send to someone outside of that niche. For instance, an advisor who works with many members of a particular union could display something that signals solidarity with that union. Not only is the signal of solidarity useful on its own, but the fact that it may mean fewer business prospects for an advisor (e.g., management or business owners who may not appreciate the signal of solidarity with employee unions) makes the signal more impactful than one that is “cheap” and would be universally or nearly universally agreeable anyway.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that consumers are influenced by factors which have no rational basis for evaluating a financial advisor (e.g., wearing a suit, quality of the office, etc.). But advisors should be careful assuming they can convince clients that this behavior is “irrational”. For many, the story they hear, and the broader aspects of the “theater” that it takes place in, will be influential. Further, the inherent conflict of interest between any financial planner and a potential client they are prospecting makes consumers reasonably suspicious of any attempts rationalize less desirable aspects of a particular advisor’s theater, so advisors trying to persuade clients to ignore these factors may struggle more than those who simply acquiesce to reality and leverage them instead.

Of course, the power of storytelling and staging the theater of financial planning can be used to both further and harm client interests—so advisors have to be careful to use it for good—but ultimately the theater of financial planning should not be overlooked. Whether it’s in the process of trying to get new prospects or convincing existing clients to implement an advisor’s recommendations, managing the theater of financial planning plays an important role.

So what do you think? Do you have any strategies for managing the theater of financial planning? Can it be easy to overlook this aspect of the financial planning process? What do you feel are the most important traits to signal to clients? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!