Executive Summary

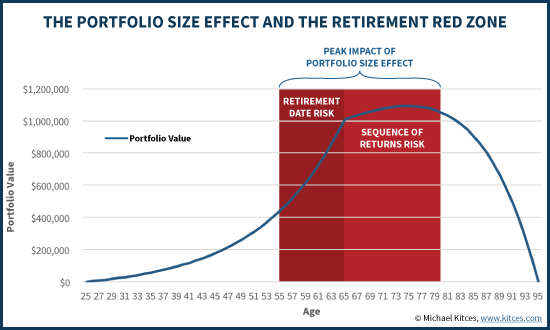

The final decade leading up to retirement, and the first decade of retirement itself, form a retirement danger zone, where the size of ongoing contributions and the benefits of continuing to work are dwarfed by the returns of the portfolio itself. As a result of this “portfolio size effect”, the portfolio becomes almost entirely dependent on getting a favorable sequence of returns to carry through.

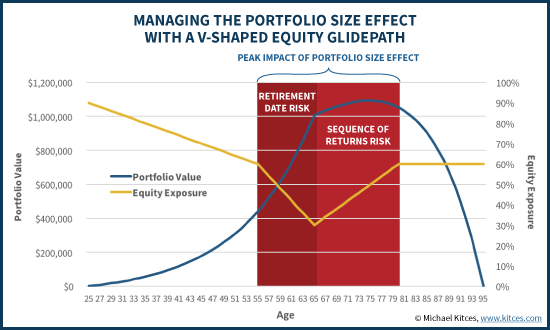

And because the consequences of a bear market can be so severe when the portfolio’s value is at its peak, it becomes necessary to dampen down the volatility of the portfolio to navigate the danger – a strategy commonly implemented by many lifecycle and target date funds, which use a decreasing equity glidepath that drifts equity exposure lower each year.

Yet the reality is that the retirement danger zone is still limited – after the first decade, good returns will have already carried the retiree past the point of danger, and bad returns at least mean that good returns are likely coming soon, as valuation normalizes and the market cycle takes over. Which means while it’s necessary to be conservative to defend against the portfolio size effect, it’s not necessary to reduce equity exposure indefinitely.

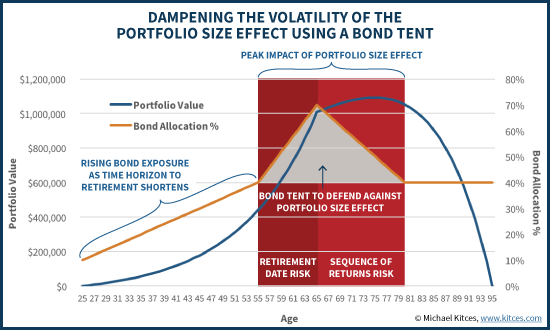

Instead, the optimal glidepath for asset allocation appears to be a V-shaped equity exposure, that starts out high in the early working years, gets lower as retirement approaches, and then rebuilds again through the first half of retirement. Or viewed another way, the prospective retiree builds a reserve of bonds in the final decade leading up to retirement, and then spends down that bond reserve in the early years of retirement itself (allowing equity exposure to return to normal).

Ultimately, further research is necessary to determine the exact ideal shape of this “bond tent” (named for the shape of the bond allocation as it rises leading up to retirement and then falls thereafter). But the point remains that perhaps the best way to manage sequence of return risk in the years leading up to retirement and thereafter is simply to build up and then use a reserve of bonds to weather the storm.

The Portfolio Size Effect And The Retirement Red Zone

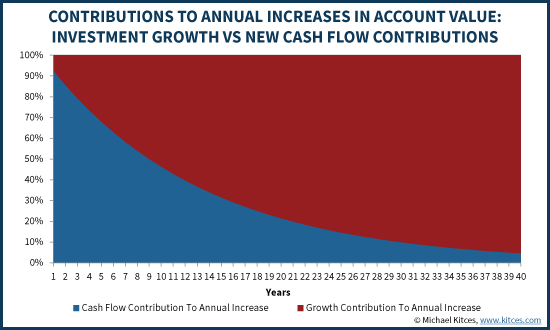

Saving for retirement is often framed as a long-term effort of systematic saving and years of compounding growth. But the reality is that in the early years, whether you save is more important than the growth you earn, because the portfolio isn’t large enough for the earnings to have a material impact. It’s only after a decade or more of saving that eventually the annual return of the portfolio begins to trump the impact of the direct contributions to it.

For instance, saving $300/month allows an account balance to grow to $3,600 by the end of the first year. In the second year, the account may grow slightly, but the increase in the account balance will again be driven primarily by the contributions (as a year’s worth of growth may still be less than a single month’s worth of contributions). After 10 years of the same behavior, though, suddenly only half of the annual increase in the account balance is driven by new contributions, while the remainder is driven by growth on the existing balance. After 20 years, growth will drive 75% of the annual increases in the account balance. After 30 years, it’s almost 90%.

This phenomenon is known as the “portfolio size effect” – the mathematical recognition that in dollar terms, the impact of a portfolio’s returns is dependent on the portfolio’s size. And while this mathematical truth may seem self-evident, it has significant implications for the accumulation and decumulation of retirement portfolios. Because the portfolio size effect means that not only does growth produce a greater dollar amount of gains on a larger portfolio, but a market decline also produces a larger dollar amount of losses.

In fact, this is one of the primary reasons why retirees face “sequence of return risk” in their first decade of retirement: because the portfolio is the largest in the first decade of retirement (even retirees who are “spending down” don’t normally spend more than their growth until at least the second decade of retirement). Which means an ill-timed bear market takes its biggest financial slice when the portfolio’s size is at its peak, potentially leaving the portfolio with too little in dollar terms to sustain the retiree’s current standard of living. After all, a “mere” 20% decline on a portfolio in a bear market evaporates 5 years’ worth of spending at a 4% withdrawal rate.

Similarly, prospective retirees in the final decade leading up to their retirement also face a problem with the portfolio size effect. The good news of a growing retirement portfolio is that it’s possible to bridge a significant shortfall in the retirement nest egg in just the last few years before retirement (because the growth is so significant in dollar terms as the account balance rises). The bad news, however, is that a bear market in the final years before retirement can set the retiree so far back that later years’ ongoing contributions can’t possibly make it up, forcing a substantial delay in retirement. In other words, the portfolio size effect leaves the prospective retiree increasingly exposed to substantial “retirement date risk” as the portfolio becomes almost entirely reliant on a few years’ worth of growth to bridge the final gap.

Simply put, the portfolio size effect leads to a substantial “retirement red zone” of danger that covers the final decade leading up to retirement, and the first half of retirement itself, where the portfolio’s value is so large that a potential market decline can have a catastrophic impact (given a fixed standard of living that the portfolio is intended to support).

Managing The Portfolio Size Effect With A V-Shaped Asset Allocation Glidepath

The double-edged sword nature of the portfolio size effect – that it makes good returns even better (in dollar terms), but market declines more adversely impactful – raises challenging questions about the optimal asset allocation glidepath through the accumulation and decumulation phase.

On the one hand, the fact that positive returns just do even more to get the prospective retiree to their nest egg goal suggests that portfolios should just continue to be aggressive, or even get more aggressive, as the retirement date approaches. After all, Shiller has noted it’s rather ironic that savers would be more aggressive in the early years (when the growth has little positive financial impact) and conservative just as they approach retirement and the portfolio’s size would make it easiest to catch up on any retirement shortfall. Similarly, Basu and Drew find that the amount of money a prospective retiree has on the retirement date is driven almost entirely by their asset allocation in the later years, and not the early years, given the portfolio size effect. And Arnott has called the presumed benefit of the conventional target date fund glidepath (decreasing equity exposure as retirement approaches) an illusion.

On the other hand, while growth can help more when the portfolio’s size is larger, and markets do go up on average (and go up more often than they go down), it’s important not to understate the consequences of how an ill-timed bear market can set back a retiree’s goals. Especially when recognizing that compounding wealth beyond a certain point has diminishing marginal utility (i.e., extra growth from the portfolio size effect is nice, but the second million isn’t nearly as rewarding as the first!). And the research going all the way back to Kahneman and Tversky’s “Prospect Theory” shows that we are risk averse in that we experience the pain of losses more than the upside benefit of gains. Accordingly, even though the portfolio size effect will arguably be positive more often than negative, Wade Pfau has shown that once a glidepath analysis incorporates these utility impacts, the conventional wisdom of decreasing equities in the years leading up to retirement makes sense after all.

And notably, as shown earlier, the potential adverse impact of the portfolio size effect applies in retirement as well. Which in turn means getting more conservative with the portfolio as its value peaks is not just about reducing equity exposure in the years leading up to retirement, but also in the first decade of retirement, too. Accordingly, our prior research for retirees has found that a “rising equity glidepath” (which is more conservative in early retirement and gets more aggressive later) can also improve retiree outcomes, by limiting their exposure to potentially adverse market volatility when the portfolio size effect is greatest.

All of which means the optimal equity exposure to manage the risks associated with the portfolio size effect over an individual’s full lifecycle would take on a V-shaped glidepath, getting more conservative in the decade leading up to retirement, remaining conservative in early retirement, and then drifting at least somewhat higher again in the later years.

Or viewed another way, if the portfolio size effect reflects when the portfolio (and the goals it is intended to support) is at the greatest risk for a catastrophe, the way to manage the danger is simply to take the least risk with the portfolio when it is the largest!

Using A Bond Tent To Dampen The Volatility Of The Portfolio Size Effect

From the traditional equity-centric perspective of portfolio management, using a V-shaped asset allocation glidepath may seem counter-intuitive, particularly when it comes to having a more conservative portfolio in the early retirement stage and then allowing it to become more aggressive again later. However, when viewed from the perspective of the portfolio’s bond allocation, the strategy appears far more logical.

After all, the fundamental purpose of bonds in a traditional portfolio is to reduce the portfolio’s volatility, which means a larger portfolio would be at less risk for a substantial financial loss. Bonds can achieve this outcome both by being an outright volatility dampener (since bonds are less volatile than stocks, swapping stocks for bonds reduces the portfolio’s overall volatility), and also as a diversifier (since stocks and bonds are not correlated, total portfolio volatility may decrease even further). Notably, in this context, the point of the bonds is not to drive returns, but to manage retirement risks and exposure to equity bear markets (which is why they’re appropriate to own, even in a low-yield environment).

Accordingly, from the bond perspective, the V-shaped glidepath turns upside down, and the prospective retiree actually accumulates extra bonds in the years leading up to retirement, and then spends down that volatility-dampening bond reserve in the first half of retirement. By the end, the retiree will finish with a bond allocation that is higher than it was in the early accumulation years, but less than it was when the portfolio was at its peak value (and therefore peak portfolio size effect risk).

In essence, the strategy to protect against the retirement danger zone and the risks that come with the portfolio size effect is to build a “bond tent” – an upside-down V-shaped extra allocation to bonds that gets built up in the final years before retirement, and gets spend down in the early years of retirement. This allows the portfolio to take shelter in the tent during the riskiest years of being exposed to the portfolio size effect – not because bonds have an appealing return, but simply because they reduce the volatility risk that becomes so severe at the portfolio’s maximal size.

Notably, there’s still far more research to be done to optimize the exact shape and the slope of the V-shaped equity glidepath and the bond tent. It’s not entirely clear how quickly during the pre-retirement red zone the bond allocation should build (i.e., the pre-retirement glidepath), nor how quickly it should be liquidated in the early retirement years. It may be that the equity exposure should be shaped more like the letter U than a V, such that the bond tent would have a wider roof – an extended period of time where greater bond allocations are held as a reserve. And the exact height of the bond tent – how high the bond allocation should reach – may be further optimized as well, especially given today’s low-yield environment (where bonds are less appealing to hold relative to historical standards, but still better than holding equities with even greater volatility and sequence risk). And of course, there are other fixed income alternatives besides traditional bonds that might be considered as “volatility dampeners” and “diversifiers” as well.

Nonetheless, a wide base of research suggests that some pre-retirement decreasing glidepath in equities (and building of the bond position) is appropriate, and even our original rising equity glidepath over the entire 30-year retirement time horizon helped defend against a subset of the most adverse scenarios (and an ‘accelerated glidepath’ over just the first half of retirement helped slightly more). Which means some kind of V-shaped equity glidepath – or building a bond tent in which the retiree can take shelter during the retirement red zone when the risk of the portfolio size effect is greatest – appears to be more effective than the “traditional” lifecycle or target date fund asset allocation glidepath, that just gets lower and lower throughout retirement, and may actually be amplifying the risk of a bad sequence of market returns!

So what do you think? Would you consider a V-shaped equity glidepath in the years immediately before and after retirement? Does the idea of a bond tent – building a reserve of bonds during the years of greatest risk – make sense as a retirement strategy? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Thank you for another interesting article. I’ve been reading your work specifically because of these articles on retirement date and sequence of returns risks. It is an approach that I am currently considering.

I am curious if there may be a withdrawal rate “floor” at which point sequence of return risk is effectively a non-issue. In other words, an alternative (or addition) to a bond tent could be a reduced withdrawal rate. For example, reducing a portfolio withdrawal rate to 3% or even under 2.5% (or based on current market valuations using CAPE10) would allow for more stocks during a V-shaped glidepath, and potentially result in more expected portfolio growth and gift to heirs. If a portfolio is 70% bonds at the peak and survives with a 4% withdrawal rate, then a portfolio with 2% withdrawal rate may only need 35% bonds at the peak.

I would also be interested in how this approach could be applied to an earlier retirement (such as 45). It would seem that retirement date risk time period would remain the same, however sequence of returns risk would be greater. Intuitively I’d expect that the V-shaped bond tent would need to plateau or have a more gradual slope. The slope through the retirement date risk period would be the same, but the slope may be more gradual through sequence of returns risk. Or does surviving the first decade reduce the impact of the following decades? Again, a lower withdrawal rate would be expected to increase portfolio longevity. An early retiree may not even need a heavy stock allocation, because over a short period of time the savings rate will be more substantial than portfolio growth rate. Finally, the bond tent may be a tool to allow for an early retiree to bide time until he or she is able to cost effectively annuitize some or all of their bond allocation, hopefully covering their basic living expenses and allowing stocks to dictate discretionary spending.

Again, thank you for the article. It would be interesting to see how market valuations, retirement age, withdrawal rate, or plans to annuitize assets, would result in changes to this retirement strategy.

Joe,

Thanks for the comments!

A few quick thoughts in response…

– Strictly speaking, we haven’t really done the research yet to optimize the shape of the bond tent. Slope of the sides, height/peak of the tent, are still open issues as far as I’m concerned. We’ve already done enough research to see the bond tent has SOME value, but WHICH tent is the BEST value is an open research question.

– Bengen himself showed safe withdrawal rates at varying equity exposures from 0% to 100%. The peak safe withdrawal rate was for a balanced portfolio, but you could go more aggressive in exchange for a somewhat lower rate. And there actually isn’t a lot of fall-off – as memory serves, the safe withdrawal rate at 100% in equities was still in the 3% to 3.5% range. However, I would raise two concerns about that approach: a) it OVERWHELMINGLY trades off lower spending today for MASSIVE upside later, in a world where 4% safe withdrawal rates and the bond tent already have a non-trivial amount of upside (to each their own, but recognize how much upside the existing rule already has); and b) I would view it as a less ‘robust’ conclusion, meaning more exposed to an ‘unknown’ future different than the historical past, since you’re less diversified across asset classes and more exposed to fundamental uncertainty of the future shape of returns.

Agreed overall, though, there are definitely trade-off options here, and more room to shape the bond tent in particular! 🙂

– Michael

Thanks for sharing this great work you’ve been doing with Mr Pfau, and your running commentary/perspectives on this topic. I do expect I will incorporate this thinking into the retirement plan for my wife and I. Both in late 40’s; I’ve finally brought our bond percentage up to more than 10% of portfolio, more than doubling it to get close to the initial approach glide path (hoping to retire at age 60 w/ 100% of pre-retirement income.) I believe my portfolio construction approach gives us a little added protection, so my initial thought is to shadow the bond path laid out above – though I have some work to do yet to get comfortable with it.

I plan to use a variable withdrawal rate that starts at 3.5% but really varies according to real cash flow needs (I expect several one-time or short-term cash flows from sales of assets/business during the first 10-15 years of our retirement, so a locked withdrawal rate structure just doesn’t make sense to me; especially as my approach is to cash flow the whole thing out to age 100.

Once I lock down a few more assumptions I’ll run this past a couple advisors and get some feedback.

Very cool — I’ve implemented the idea and methods here in a lot of ways, but seeing the graphics outlined around it put it to life in a good and visual way. Thanks!

Michael,

I agree that it makes sense to reduce risk at the retirement date because of the portfolio size effect and sequence of returns risk. Does an increase in the allocation to bonds reduce risk? Don’t we have a sequence of returns problems for bonds, as well? (especially after a 35-year bull market)

Thanks,

Rob

Rob,

Yes, there is a sequence of returns risk effect with bonds (or anything that has return volatility). However, the sequence risk of bonds is miniscule compared to the sequence risk of stocks, given the drastic difference in potential drawdowns and recoveries; even “bad” bond bear markets in intermediate government bonds rarely produce an annual decline more than a few percent, while “bad” stock bear markets 35% or more.

Not to say that the risk of bonds is zero, but relative to the sequence risk of stocks, it’s so overwhelmed by stock volatility that it’s still an improvement in outcomes. Even at low rates. And for those who really want to reduce bond exposure, the alternative would be cash (T-Bills) – see https://www.kitces.com/blog/accelerating-the-rising-equity-glidepath-with-treasury-bills-as-portfolio-ballast/

– Michael

Michael,

Thanks.

You’re right that the annual volatility of stocks is far higher than the volatility of bonds. Perhaps I framed my question incorrectly. I’m concerned about a rise in interest rates over three to five years, and the cumulative impact on retirement portfolios with a high allocation to bonds. Historically, the returns for stocks tend to be mean-reverting, while returns for bonds tend to have long cycles. So we could see a few years in a row where bonds lose money.

As you noted, the obvious answer is cash. Problem solved.

: )

Rob

Rob,

Indeed, I realize that “cash” isn’t the exciting answer, given its even-worse yield. But it is the place to ‘hide’ in rising rate environments.

That being said, you might want to look back at the returns on intermediate government bonds as interest rates rose from under 4% in the mid 1960s to over 12% in the subsequent 15 years. There were hardly any years where they even registered a negative annual return at all (though there were years when they lost to TBills). As much as we tend to talk about the fear and consequences of rising interest rates, they generally only rise “so fast” in any particular 12 month period… which makes rising rates more of a 15-year structural headwind, than an overt near-term sequence risk issue. Just food for thought. 🙂

– Michael

Michael,

Good point, and thanks for the opportunity to think this through.

Perhaps I’m too worried about rising rates because I haven’t:

1) Studied enough periods where rates rose.

2) Run simulations that modeled the impact.

I’m guessing that I’m not the only advisor who faces this challenge. Perhaps this is a topic you could address in a future issue, time permitting.

And thanks for mentioning cash, which doesn’t get enough respect. As someone who co-authored a book on alternative ETFs and mutual funds, I’ll be the first to say: “The more I study liquid alts, the more I like cash.”

; )

Rob

P.S. Guess I won’t get invited to speak on liquid alts any time soon.

Robert and Michael,

Laddering bonds and holding until maturity can also address the risk of a rising interest rate environment. While this is extra work compared to putting in bond funds, this can show additional value vs. robos.

Rob,

Good idea.

I used laddered bond ETFs for preciscely the reasons you cited. I do it because it spreads out my interest rate risk, and I can reinvest at higher rates if rates rise.

Perhaps this practice will spread to robos, though I personally believe that ladders work best when they are customized for a particular client’s goals.

Rob

Does the use of a series of maturity dated laddered ETF bond fund, like those from Guggenheim Bulletshares help solve this problem of covering that 10-15 year danger zone period? And using them appears to be a lot less work then purchasing individual bonds to ladder.

Tom,

Yes, in this context I think Bulletshares is a reasonable alternative to a bond or CD ladder. Generally tackling the same issue with the same approach, just a different implementation vehicle.

– Michael

You might be interested in this: http://www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2013/06/11/bursting-the-bond-bubble-babble

Evidently there is no need for lifetime joint income annuity income, and their mortality credits in your analysis Michael? It would seem that a guaranteed lifetime income floor to address longevity risk could prove helpful too, or not?

WiseOwl,

Certainly immediate annuities (or in particular, DIA/longevity annuities) can help to address a longevity risk issue. Technically, the focus of this article was just the sequence risk aspects, not the longevity risk side (the potential that the time horizon extends longer than the sequence risk chart shown here).

We’ll be doing some further writing and work on the integration of the two. But need to set the foundation, first. 🙂

– Michael

Thanks, I was thinking replacement of some portion of the bond allocation with the annuity substitute, still leaving a meaningful bond element/percentage for conversion back into equities as the retiree ages through his/her adverse sequence period, and, reduced PE 10 multiples.

I agree with WiseOwl and Joe that PE multiples should be part of this discussion too, particularly when the multiple is significantly outside its norm, e.g. one standard deviation either way. Schiller’s CAPE seems to be a good place to start for PE data.

If you consider an income annuity to be a fixed income alternative, then a decision to delay social security benefits is equivalent to increasing bond holdings through the beginning date by the value of the “deferred income annuity” being purchased by the delay. Starting social security benefits is therefore equivalent to decreasing bond holdings as the value of the future benefits declines over time. So delaying social security is a form of partially implementing the bond tent strategy during the critical years.

Michael,

Interesting as always, but I was reminded of an earlier post you did in which you pointed out that it was not the sequence of return risk, per se, that was significant for retirees so much as the sequence of REAL returns. This is born out by Bengin’s work as well where the failures had much more to do with inflation than with sequence of nominal return.

It would be interesting to see how inflation would factor in here. After all, in the absence of an extended period of deflation, inflation compounds, while market downturns tend to recover if the equity holdings are left intact. Accordingly, and it may well effectively come to the same thing as the “tent”, rather than than focusing on dampening the overall volatility of the portfolio with bonds, wouldn’t focusing on maintaining a reserve in terms of 5, 7, even 10 years’ of withdrawals accomplish the same thing even more effectively and with greater flexibility?

Hi Michael. Nice work as always. The bond tent starts to look a lot like asset dedication. Your analysis is consistent with what Professor Huxley and I have found. Putting individual bonds on the front end of the portfolio definitely helps reduce the impact of sequence risk, especially when retired clients defer Social Security (which puts additional sequence risk early in retirement). Unfortunately, bond funds won’t work, especially in the current interest rate environment. Rising rates and systematic withdrawal create their own sequence risk for bond funds. But timing individual bonds to cash flows can be complicated. Still, your research confirms our conclusions about bonds on the front end of a retirement portfolio to protect against sequence risk on the equity side. Of course, asset allocation will need more room to float in order to ride through nasty markets.

…so 3 years later, with rates at an all time low, bond funds are specifically at risk since rates pretty much have no place to go but up, which of course will lower the price of the bond funds. Any thoughts on defined maturity bond ETFs? They should behave more like individual bonds if held to their maturity year.

Excellent analysis, Michael:

In applying the bond tent approach would you suggest adding the NPV of a couples anticipated Social Security stream of payments to the bond allocation in the Red Zone?

Egalitarian,

Strictly speaking, the fact that the NPV of Social Security benefits is a fixed-income self-depleting asset technically means that it already IS a partial bond tent strategy. If you calculate (and annually update) the NPV of Social Security for an otherwise static asset allocation, the household’s overall asset allocation depletes the fixed portion and allows the equity percentage to rise as the Social Security value depletes.

From the academic perspective, I’d say that ideally the optimization of the bond tent glidepath (how much more in bonds exactly, built how quickly, and depleted how quickly) should incorporate Social Security.

From the practical perspective, though, that’s challenging, because most people tend to “bucket” the two entirely separate, and adjusting portfolio asset allocation to accommodate non-liquid Social Security NPV calculations will be mentally stressing for many (as it will likely necessitate the pure portfolio portion to be even MORE equity-centric). See https://www.kitces.com/blog/valuing-social-security-benefits-as-an-asset-on-the-household-balance-sheet/ for some further comments on this.

– Michael

Mr Kitces

A great article. Do you still adhere to the same bond tent concept in the 2021 negative yield environment for TIPS and other low risk bonds. What alternatives are there. I retire in 14 days at 50/50 balance.

Thanks.

Michael; As a 67 yo in retirement I have followed your (and Dr. Pfau”s) articles on this topic and have incorporated your findings and recommendations into my investing strategy. My question concerning this article is that you leave out your updated conclusions (AAII Journal, 4/15) incorporating a dynamic valuation based strategy; i.e. increasing stock exposure when the Shiller CAPE ratio is low and decreasing equity exposure when elevated (26.8 today). Do you still recommend a valuation based allocation approach?

Thanks,

Matt

Matt,

Thanks for reaching out, and great question.

Conceptually, the bond tent isn’t actually in disagreement with the dynamic valuation strategy. Both are built around the concept of reducing equity exposure (and increasing bond exposure) as the portfolio peaks in early retirement, to manage the sequence risk.

The “only” difference is that the valuation-based strategy uses market valuation to determine the timing of adding/subtracting the bond tent. This article is meant to be a ‘valuation agnostic’ baseline, where if you don’t otherwise KNOW the valuation, by default you would apply the bond tent mechanistically with time.

Ultimately, I still expect that valuation-based strategies will prove to be a better way to apply and remove the bond tent, versus a purely time-based strategy. Functionally, that’s what our valuation-based research has shown – that valuation-based is more effectively than time-based (e.g., from the AAII Journal, and also published here on the blog at https://www.kitces.com/blog/valuation-based-tactical-asset-allocation-in-retirement-and-the-impact-of-market-valuation-on-declining-and-rising-equity-glidepaths/ ).

Though in the end, I still view the entire discussion of how to optimize the bond tent itself – how high to build it, how quickly to build it, how speedily it is spent down, and whether those adjustments are made based on time or valuation (or both) – is an open area for further research. That may just end out being ‘better’ refinements to valuation-based (as I’m skeptical we’ll find a time-based alternative that is superior given the dominance of the valuation-based outcomes already). But there’s still room to try to optimize further. (An area of future research I still intend to pursue deeper!)

– Michael

Michael,

Heading into retirement with 40% in bonds, what is to prevent a retiree from just spending from bonds if the market is tanking? The retiree could do this for some time (10 years?) if need be. Of course, the allocation ratio would change radically, but if one believes that these episodes have limited duration there should come a time when the stock situation normalizes and rebalancing to a 60/40 norm is possible. Building a bond tent would lengthen the time one could wait for the market to recover, but how great is the risk that would be addressed? And how could the cost of that insurance be balanced against the lost gain from the tent versus investment in a normal stock market?

This is a philosophical question. I’ve been retired since 2002, weathering several serious market declines. Could the issue instead be ‘how’ the bond dollars were invested? If they were short or close to cash, it seems that 40% should be enough, short of a cataclysm that brings all houses down.

I like your thinking on using the bond funds in down years and rebalancing after the market recovers. Have you done any analysis on this?

Could you clarify the last point; how does the traditional glide path (decreasing equity exposure) aggravate sequence of return risk?

Also, why not hold a bond allocation that allows RMD withdrawals from the bond side of the portfolio so you are never forced to sell equities during a bear market. My social security and RMD withdrawals cover 90% of my fixed expenses so I am holding over 5 years of expenses (less social security) in my bond portfolio. Does that seem reasonable?

-Tom S

Would a cash tent be more effective than a bond tent in the retirement danger zone? The lower the volatility, the lower the sequence-of-returns risk. Volatility comes from interest-rate fluctuation as well as inflation/deflation fluctuation. I am considering a combination of FDIC-insured bank deposits and the short-term treasury inflation-protected securities ETF (VTIP). How should I determine the optimal allocation between the two in my tent?

Isaac,

We haven’t fully completed research to optimize what types of bonds would be best IN the bond tent.

A separate study we published last year found that at least longer-term bonds is probably NOT the answer (for all the interest rate volatility reasons you cited), and that Treasury Bills would be superior. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/accelerating-the-rising-equity-glidepath-with-treasury-bills-as-portfolio-ballast/

Ultimately, though, the optimal type is still up in the air, and whether it’s Treasury Bills, or CDs, or perhaps intermediate term bonds that have some term premium for being longer-term but not so long-term that interest rate risk is amplified.

The underlying principle, though, is that you almost certainly wouldn’t want to take default risk (i.e., corporate bonds) because that’s correlated to market/economic risk, and that you certainly wouldn’t want to take “significant” interest rate/duration risk. But where the balancing point is between cash, CDs, and short-to-intermediate-term bonds is still an open research question.

I hope that helps a little!

– MIchael

Thanks Michael. Will your research take *short-term* Treasury Inflation-Protected Security (TIPS) into consideration? Inflation is a risk because the danger zone is 20-year long. TIPS/CPI is probably a better inflation hedge than increasing bond duration.

This is a really great post and I look forward to seeing you further develop the specifics of the bond tent. One thing to consider with interest rate risk is the additional downside protection during an equity crash. Because of this you should be able to hold a smaller allocation to bonds for the same level of protection. I think of adding duration as similar to leverage. I’m not arguing this is the right approach for the current environment but could make sense down the road.

So i was wondering if increasing equity in your home by paying off the mortgage is a form of a bond tent. By paying off my mortgage, and then living off that equity (after buying a smaller home) im hoping that this would cushion me from any possible market downturn.

Wow, gliding up to 70% bond allocation is much higher than I was anticipating. It makes sense though.

I like to have no bonds and hold Berkshire Hathaway instead.

Is there new research or data on recommended equity glide path? For my practice, we typically allocate enough bonds such that the client has 10 years worth of withdrawal amounts in bonds. I believe the longest recovery time of the US stock market is around 9 years, following the 1937 crash/great depression, to 1946, though this was a time when we didn’t fully understand the power of fiscal & monetary policy. So having 10 years worth of bonds should be enough protection against any downturns. Thoughts about this??