Executive Summary

If there’s one fundamental takeaway that’s been drawn from the research on safe withdrawal rates, it’s the fact that market volatility really matters during the retiree withdrawal years. Even when long-term returns average out in the end, if the sequence of volatile returns is unfavorable, there is a danger that ongoing distributions during the “bad” years early on could deplete the portfolio before the “good” years ever show up.

As a result, many advisors and their clients use strategies that will avoid taking distributions from asset classes like equities during down years – for instance, setting aside “buckets” as a reserve against market crashes, and/or creating a series of “decision rules” that might simply state outright that equities will only be sold if they’re up, otherwise bonds are liquidated instead, and cash/Treasury bills will be used if everything else is down at once.

Yet when such a decision-rules strategy is paired with simple rebalancing, it turns out that the outcome is no better than merely managing the portfolio on a total return basis without the decision rules at all! The key, as it turns out, is that rebalancing alone already has an astonishingly powerful effect to help avoid unfavorable liquidations, as the process systematically ensures that the investments that are up (the most) are sold, and the ones that are down (the most) are actually bought instead! Which means in the end, we may not be giving rebalancing nearly the credit it deserves to accomplish similar – or even better – results than buckets and decision rules alone, and that such approaches are better purposed as explanatory tools for clients than actual systems for generating cash flows in retirement!

Liquidation Decision Rules And Managing Sequence Of Return Risk

To avoid the danger of selling equities (or any other asset class) after a loss, one of the most popular solutions is simply to establish a series of “decision rules” that outright dictate that equities will not be sold in such circumstances.

For instance, a retiree separates their portfolio into three buckets: #1 holds equities (e.g., S&P 500) for 60% of the portfolio; #2 is invested in (intermediate government) bonds for 30% of the portfolio; and bucket # holds the last 10% of the portfolio in cash (Treasury bills).

Once these three buckets are established, the retiree then might use the following decision-rule framework for liquidations:

1) If equities are up, take the retirement spending from equities

2) If equities are down but bonds are up, take the spending from bonds instead

3) If both equities and bonds are down in the same year, take the distribution from Treasury bills

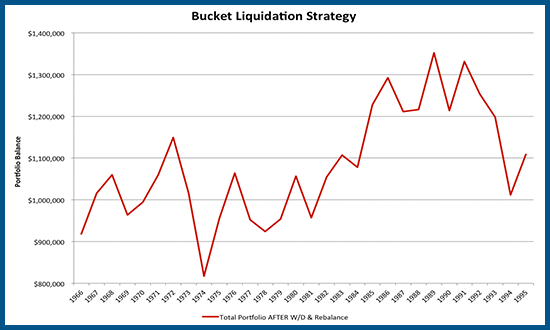

Using this decision-rules approach, the chart below shows the retiree’s results if retirement begins in 1966, assuming a 4% initial withdrawal rate, distributions adjusted each subsequent year for inflation, with liquidations occurring at the end of each year, where the portfolio is rebalanced back to its original 60/30/10 allocation at the start of each year. (Transaction costs are assumed to be negligible, taxes not included.)

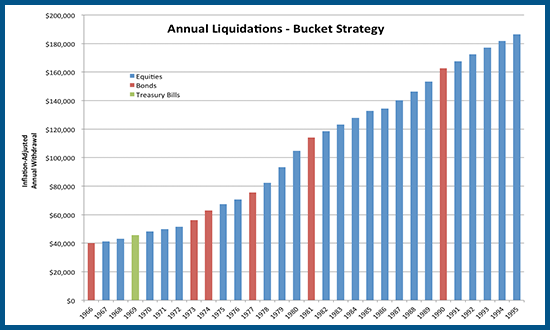

A deeper look at the year-to-year returns shows that in fact, the liquidations really did have to come from varying asset class “buckets” over time to avoid ever selling after a decline. Given that most of the time equities have positive returns, in 23 years the distribution really did come from equities; however, in 6 years it came from bonds, and in one year (1969) the distribution came from Treasury bills (as both stocks and bonds were down that year). The chart below summarizes the source of liquidations from year to year.

Thus, as the outcomes highlight, the retiree really can avoid taking distributions from investments that have declined, and in fact the approach allows the retiree to effectively preserve principal at a 4% initial withdrawal rate even through this difficult time period (leaving over nearly all the principal at the end to boot!).

Managing Sequence Of Return Risk Via Rebalancing With A Total Return Approach

For many advisors, the goal of managing a portfolio is to manage it holistically on a total return basis, which is not necessarily consistent with a decision-rules-based buckets liquidation strategy. With a total return approach, portfolios are often still rebalanced systematically to keep them on target (which will trigger some sales and purchases), but there is no overt strategy to avoid taking retirement income distributions from asset classes that were down in the prior year and only generate distributions from those investments which were up.

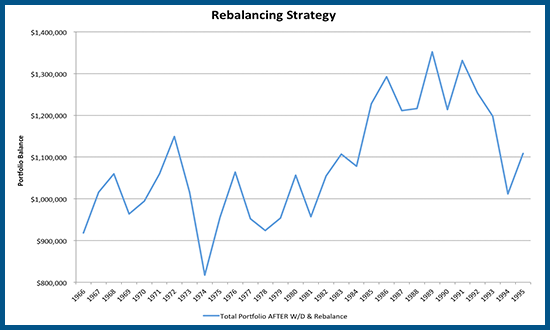

Nonetheless, we can evaluate the effectiveness of taking systematic withdrawals from a total return portfolio that is rebalanced annually. Accordingly, the chart below shows the retiree’s results if retirement begins in 1966, assuming a 4% initial withdrawal rate, distributions that are arbitrarily taken pro-rata (60/30/10) from each asset class at the end of every year, with the portfolio rebalanced back to its original 60/30/10 allocation at the start of each year. (Again, transaction costs are assumed to be negligible, taxes not included.)

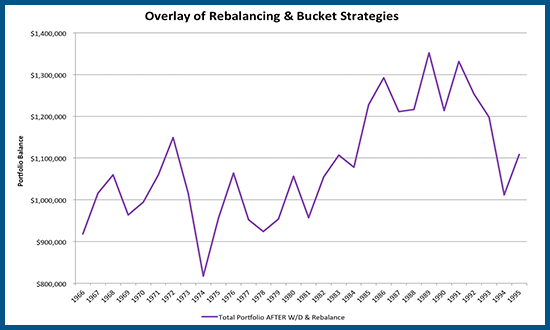

Notably, the results appear quite similar to the decision-rules strategy. In fact, if we graph them together…

As the results reveal, the decision-rules strategy (red line) coincides precisely with the total return rebalancing strategy (blue line), producing a (red plus blue makes) purple line as the colors meld together! In other words, the results are not just similar; the aforementioned decision rules bucket approach is actually having no impact at all over the total return rebalancing approach, as they are precisely identical outcomes at every step along the way!

Decision Rules With Buckets, Total Return Rebalancing, And Managing Sequence-Of-Return Risk

To understand why the decision-rules-based buckets liquidation strategy and the total return rebalancing strategy were the same, it’s necessary to go back to the assumptions used for the decision-rules framework, which were:

1) If equities are up, take the retirement spending from equities

2) If equities are down but bonds are up, take the spending from bonds instead

3) If both equities and bonds are down in the same year, take the distribution from Treasury bills

Using this decision-rules approach, the chart below shows the retiree’s results if retirement begins in 1966, assuming a 4% initial withdrawal rate, distributions adjusted each subsequent year for inflation, with liquidations occurring at the end of each year, and the portfolio rebalanced back to 60/30/10 at the start of each year.

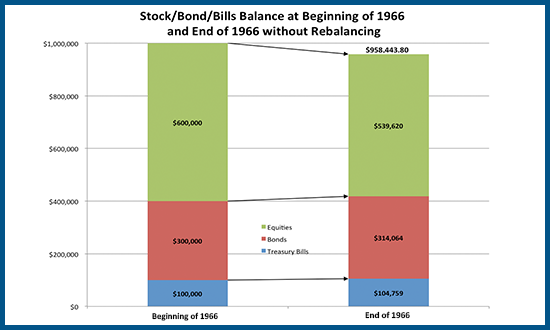

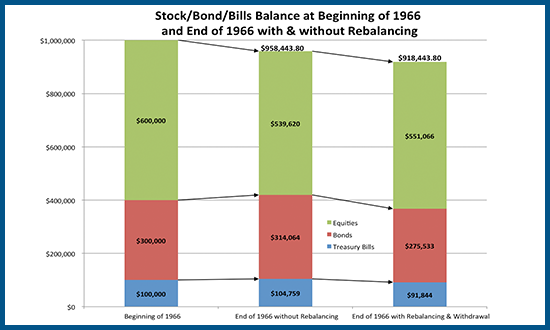

The key, here, is the final sentence: once a portfolio is going to be rebalanced every year, the impact of decision rules is made null and void and the buckets are essentially just an asset allocation mirage, because the total amount of withdrawals is always the same (regardless of which asset classes it’s taken from) and the final allocation is always the same (due to the rebalancing). For instance, if we look back to the first year of 1966, the chart below shows the results (before any rebalancing or withdrawals through the year):

The portfolio that starts out with $1,000,000 finishes the year at $958,443.80, due to a combination of a fairly significant equity loss that is only partially offset by gains in bonds and bills. And because a $40,000 withdrawal must occur (from some asset class or another), the ending balance after withdrawals is going to be $918,443.80. Which means, no matter where the withdrawal is taken from, the asset class allocations will ultimately be rebalanced back to 60/30/10, which means $551,066.28 in equities, $275,533.14 in bonds, and $91,844.38 in bills. Changing which pre-rebalancing asset classes generate the distribution could impact the (assumed-to-be-negligible) transaction costs, but it doesn’t change the account balance ($958,443.80) right before the liquidation, nor does it change the 60/30/10 allocations of the remaining $918,443.80 right after the liquidation and entering the following year!

What is also notable about this rebalancing result is that the investor will actually be selling bonds and bills to buy equities. In other words, the decision rules are not actually necessary at all to ensure that equities are not sold when they are down; in fact, rebalancing alone not only ensures that result, but also leads to the purchase of even more equities when they are down to benefit from the rebound in the future!

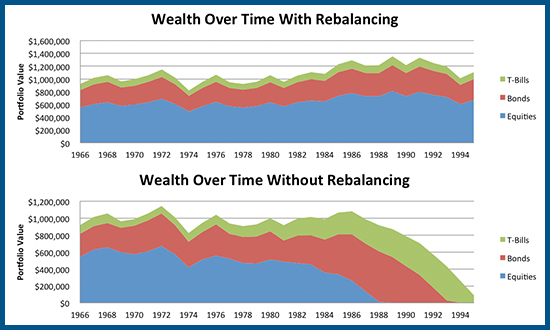

In fact, the chart below shows the results of just using the decision-rules approach without rebalancing along the way. As the results reveal, it is worse – so much worse, that the portfolio barely has anything left at the end with the decision rules alone, while the outcome is drastically better with rebalancing because it actually buys equities during dips!

In other words, not only are the decision rules actually irrelevant once the portfolio is regularly rebalanced, but eliminating the rebalancing is so damaging that the decision rules alone actually lead to a worse outcome for the portfolio!

The reason is that in an adverse scenario like this – especially with an equity decline from the start – the ongoing inflation-adjusting withdrawals become so significant that they eventually overwhelm the equity portfolio, especially when there are not any additional purchases of equities after they go through a decline. As the chart below shows, without rebalancing back into equities after market declines, the inflation-compounding impact of the withdrawals eventually depletes the equity exposure altogether, and of course once the equities are gone the remainder of the portfolio – now entirely in fixed income – struggles to keep up.

Practical Implications For Financial Planners Managing Sequence-Of-Return Risk For Retirees

So what does all of this mean for financial planners trying to help navigate sequence-of-return risk for their retired clients?

The first key point is simply to recognize the “awesome” impact of rebalancing itself. While classically viewed as a mechanism to just “keep the portfolio on target with its allocations”, the reality is that rebalancing itself is a tool to ensure that only the investments that are up are sold, and that the investments that are down are actually bought as well. To the extent a retiree is taking ongoing withdrawals, the effective result is still the same; rebalancing implicitly assures that all distributions end out coming from the asset classes that were up (the most), and never from those that were down (the most).

The second key issue is to recognize that decision-rules strategies liquidating from various buckets may be insufficient to sustain retirement as well. Not because they’re ensuring that equities don’t get sold when they’re down, but because they fail to buy even more when equities are down. In other words, the bond and cash buckets need to do more than just generate retirement distributions when equities are down; they also need to be deployed to proactively buy more equities after they’re down (something that automatically occurs with rebalancing, but not with buckets alone), an indirect methodology that ensures the retiree "sells high and buys low" to enhance long-term returns. (Sidenote: This is also why a systematically rebalanced portfolio is a better means to implement a rising equity glidepath than “just” a buckets-based liquidation strategy.)

In other words, don’t underestimate the incredible impact that rebalancing really does have in a portfolio, from “automatically” ensuring that liquidations come from investments/asset classes that are up, to also creating a process that allows the retiree to buy even more of an asset class when it is down. And of course, the more (not-perfectly-correlated) asset classes the retiree holds, the greater the opportunity for rebalancing to exert its favorable effects (i.e., the outcomes may be even better than the 3-asset-class example here). And in the meantime, be cautious about decision-rule bucket strategies that can actually go so far as to adversely distort the portfolio in a manner that leads to worse outcomes (e.g., by leading to an excess cash position, or by failing to buy more equities after a decline and allowing equities to be depleted too rapidly in the event of a bad return sequence)!

Nonetheless, the point of all this discussion is not to make the case that decision-rules bucketing strategies are inferior. To the contrary, as long as they are implemented along with rebalancing, their results are exactly the same. And if clients are more comfortable with bucketing strategies – if only because they appeal more naturally to our tendency towards mental accounting – then so much the better. But just be certain to recognize that while it may be more effective to explain portfolios as a series of buckets to clients, be cautious not to allow the asset allocation to become distorted by trying to manage the portfolio that way!

Your blog is very interesting. It shows how difficult it is to develop “decision rules” to manage Sequence Of Return risks. The rules need to be much more complex in order for the portfolio to survive the test period. You have convinced me that “decision rules” cannot beat the Total Return Rebalancing approach.

You didn’t really test a “Bucket” strategy as your title suggested. I would like to know how a “Bucket” strategy (like the one in your blog “Are Retirement Bucket Strategies An Asset Allocation Mirage?”) would compare to the Total Return Rebalancing approach.

Bob,

I didn’t really explain it this way in the article, but if you said the cash/bonds/stocks in this article were “Bucket #1, Bucket #2, and Bucket #3” (holding cash for short-term bucket #1, bonds for intermediate-term bucket #2, and equities for long-term bucket #3), you’d have the same conclusion.

Buckets (and decision rules) aren’t inherently bad. They can just unwittingly introduce some harmful liquidation or asset allocation effects. You can avoid those effects by ALSO rebalancing, but at that point you really just have a total return rebalanced portfolio anyway.

– Michael

Michael-

Great article. Just a couple of points.

(1) I interpret some replies here to imply that the result for “buckets” would be different (better?) if you just use the buckets in order (1,2 3; cash, bonds, stocks) instead of the annual adjustments in your analysis. Your balance/no balance analysis should extinguish that belief.

(2) Regarding “decision rules”, there are, of course, more types of decision rules than described here. For example, those that accompany the Guyton_Klinger methodology, with which you’re intimately familiar. That approach (which I follow) is more along the lines of Larry Frank’s comments regarding spending adjustments based on portfolion value (PV). IMO, such PV based decision rules are more effective.

(3) jrpower’s comment on the psychological benefit of having a cash buffer is a good one, at least for me. We do that even though I know the benefit is mostly in my mind. But, hey, that’s where I live 🙂

Great post!

Mark

I too feel the “cash buffer” is good for where I live

An interesting Blog Michael! The results make sense over the long run since both are really total return strategies – since all the money spent needs to come from the whole portfolio over the long run.

The most important decision rule though that would impact results greatly – is the decision to spend a little less during down years, and a little more during great years, with “normal” spending during the “normal” market years.

I posted a comment with a method to measure spending for Needs versus Wants to Wade’s post here http://wpfau.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-yin-and-yang-of-retirement-income.html … basically a way to use the portfolio’s standard deviation to separate out exposure of the portfolio to types of expense categories. How much of the portfolio value may be allocated towards Needs (necessary expenses) and the remainder of the portfolio value are Wants (discretionary expenses)?

Just because the portfolio value changes doesn’t mean a large part of that portfolio value wouldn’t be consistently available for basic needs expenditures. It simply means that some part of the portfolio value wouldn’t be available for discretionary expenses at times, while it would be available at others. There are a couple of ways to measure that dividing line – standard deviation being the easiest, with POF being another … both are really related to percentage of simulation failure rates.

I believe that such a perspective would aid in recognizing your blog’s point about allocation decisions over the long run. There is no real difference. The differences in outcomes come from spending decisions.

Great post Michael!

Michael, interesting research as always. Mathematically, rebalancing at the same time as withdrawals are made has exactly the effect you’ve noted. But I rebalance based on triggers, i.e., when asset class percentages have shifted beyond a certain point, rather than annually. When rebalancing that way, the results with and without buckets/decision rules would certainly be different, but I have no idea how much or in which direction. Have you looked at that?

Neal,

Thanks for the comment.

In point of fact, I’m an advocate for trigger-based rebalancing as well based on the research out there. The calendar-based was primarily for illustration purposes and to make the point.

On the one hand, you could approach the issue by simply deciding that whenever you have a trigger-threshold rebalance, you simply free up the next chunk of cash at that time. If the target is simply to hold at least 1 year’s worth of cash, you just need 1 trigger per year to time that liquidation need.

On the other hand, as transaction costs continue to fall towards zero, arguably there’s no actual need to do that anyway. The rebalancing transaction can occur when it’s due, and the liquidation can occur when it’s due, with negligible impact if there are negligible transaction costs. Or conversely, at the moment you do a liquidation, simply take it from whatever is up the most, and you’ll implicitly be doing a partial rebalancing transaction anyway, and then you can still do your trigger-based rebalancing whenever appropriate?

– Michael

The last paragraph is exactly what I was thinking. Thanks for the confirmation!

Love the article – in that case – can an argument for a balanced fund (I.e. A balanced index or lifestyle fund) be used instead of the 2 buckets with cash kept separately?

Neil,

Yes, that’s feasible, and in practice we often recommend clients have a “reasonable” set-aside for cash anyway, just to avoid an unnecessary short-term liquidity crunch and to minimize the (admittedly already pretty low) transaction costs.

The only caveat is that there is such thing as “too much” cash. 3+ years’ worth of cash can just be a drag on the total net worth – see http://www.kitces.com/blog/research-reveals-cash-reserve-strategies-dont-work-unless-youre-a-good-market-timer/ – but something like 6-12 months should be minimal impact (in terms of return drag) while just expediting the process a bit.

– Michael

Thanks – love the blog

Is the “3+ years worth of cash” a “drag on total net worth” possibly due to the historic data being…very low interest rates? Or could the “excess cash” be used in down years to either spend or buy to rebalance? Assuming an increasing equities glide path?

Heck cash is great in down years to pay taxes on a roth conversion, say if you suddenly get an inheritence. It's always great to have around but money invested in the market has the more value than sidelined cash. Someone living the 4% rule with a year in cash has 96 percent in the market/bonds while someone with 3 years of cash has only 88 percent. This starts to add up quickly. I'd say the moneymarket will allow a higher percentage in cash to be less a drag but even at 5 percent yield in moneymarket stocks should be better.

Interesting and helpful article. A separate discussion that would be interesting would be the effect of rebalancing on long term returns for those not taking withdrawals.

Curtis,

I’ve written a bit about the standalone effect of rebalancing in the past, and will be doing more in the future. The short answer is that the raw return benefit of rebalancing is somewhat modest in the long run, and can even be “harmful” to returns in some situations (see http://www.kitces.com/blog/is-rebalancing-supposed-to-enhance-returns-or-reduce-them/ ), though there are other benefits that mean it would likely be done anyway (e.g., managing risk drift).

The particularly strong benefit you’re seeing here is a function of how much distortion a bucket liquidation strategy can cause without rebalancing.

– Michael

Michael, Great article, thank you. Have you or anyone that you know done research on how much of the sequence of returns problem is mitigated by the rebalancing and taking withdrawals at the same time as noted here. In theory if you are always taking form the sector that is relatively “up” I would think that a part of the problem goes away, but I don’t know how much.

Jim,

I’m not sure that’s going to be particularly material.

Ultimately, the real driver of sequence-of-return risk is not bad years, it’s bad DECADES. Intra-year liquidations aren’t probably going to be a huge driver of the outcomes there (and even the transaction cost savings may be negligible just given how inexpensive it is to do a simple trade these days?). See http://www.kitces.com/blog/understanding-sequence-of-return-risk-safe-withdrawal-rates-bear-market-crashes-and-bad-decades/

– Michael

Michael,

There’s an interesting discussion taking place on Adviser Perspectives driven mainly by Michael Edesses) arguing for a floor (to support necessary as opposed to discretionary spending) in safe, inflation adjusted assets, such as TIPS or an inflation indexed annuity of some sort. Clearly, that strategy can’t be entirely reconciled with a rebalancing strategy that always requires selling bonds and buying stocks in a bear market. And even Bill Bernstein suggests that for some investors whose portfolios are drawn down sufficiently they have no choice but to annuitize.

But can’t this strategy and a floor requirement be “mostly” integrated; such that the investor is constantly on the lookout for that death spiral moment where they can’t rebalance into equities and/or they can no longer be an “investor” and must annuitize.

As Larry Swedroe said in 2009, “Failing to rebalance is a misdemeanor. Panic selling is a felony.”

Steve,

To me this question confuses a floor-with-upside strategy, and how you invest FOR the floor in the first place. Both TIPS or annuity strategies and a portfolio-based strategy can form a floor – see http://www.kitces.com/blog/annuities-versus-safe-withdrawal-rates-comparing-floorupside-approaches/

Though as you note, some flooring strategies create liquidity constraints that can create subsequent problems with the inability to rebalance. :/

– Michael

Michael,

Thanks for the reference back to the floor with upside piece. That was quite a conversation.

I think some of the confusion comes from the notion that the floor is: 1) sometimes within the portfolio – which is what a balanced strategy with rebalancing is – especially for someone who doesn’t have a pension or social security (rare) or for whom those income streams are immaterial to their overall spending desires, or 2) entirely outside the portfolio. I consider a decision to annuitize a part of the portfolio as taking that part of the floor entirely outside the portfolio and creating a new portfolio to work with necessitating an asset allocation that accounts for the guaranteed income stream. Or (and this is the most frequent and difficult one), 3) when the client has only done most, but not all, of the work required to differentiate between necessities and almost necessities so we can’t know exactly what the spending floor is and how much capital (and in what form) is needed to fund it.

For example “spending time with grandchildren” is not food, shelter, clothing and medicine. And a lean budget for that is going to look different than a generous one. As a planner, if I can get a client to just recognize these gray areas and not necessarily completely sharpen the pencil, I think that’s good enough.

Thanks so much Michael for all your leadership thinking.

Steve,

In point of fact, one of my other ‘gripes’ about flooring strategies (whether it’s done within the portfolio or outside) is that I’m not convinced that setting what the floor SHOULD BE is nearly as straightforward as has been suggested.

Can you really imagine the conversation with clients about whether “cable TV” or “dinner with friends” or “vacations with grandchildren” is an “essential” or “discretionary” expense, and actually force them to put it in one group or the other so that you can set the floor? Ouch. (See http://www.kitces.com/blog/the-problem-with-essential-vs-discretionary-retirement-strategies/ for some further thoughts on this.)

Certainly, people who are struggling with retirement and affording it may have to cut back to essentials, and clearly there are some clients who view truly frivolous expenses as “essential” when they’re not. But the line is often not nearly so clear, and that gets really challenging when trying to match a concrete floor to a not-so-concrete essentials list.

– Michael

Terrific piece, Michael. I would not argue at all with the data or conclusions. The only matter I think that is missing is the behavioral finance reality. Once folks have “retired” and have no new income appearing, they tend to very greatly fear the shrinking portfolio. We in the profession know that phenomenon, however real, is typically transient. The well allocated portfolio has sufficient “elasticity” and resilience to weather the storm. But that knowledge, however fact based, is not sufficient to calm the troubled waters in a downturn of markets. Think of it this way. If you are sailing and a storm crops up, knowing that the seas will eventually calm again doesn’t resolve the fear of imminent capsizing. If the client really has more money than they need, and by a long shot, the argument is easy. What I tend to like about the analysis is that holding a cash equivalent “bucket”, if re-balancing is done properly, doesn’t harm one much. And the piece of mind that it buys is well worth the modest loss in total assets at the end of the day.

What I like to do is set aside a bit larger allocation to cash and equivalents (say two years of need) and then allocate the balance to bonds, stocks and some other classes. The latter is re-balanced annually. This approach has worked rather well for my clients over the past several years. They can sleep at night (with an occasional sedative in 2008/2009) and seem to remain in a solid position. Most of my clients are not sophisticated investors, but they do grasp the fundamentals. Having that cash position that is either held as a reserve or used and “recharged” keeps them happy about their lives. In the end, that is what is most important (IMHO).

The article considers two extreme solutions for rebalancing the buckets: (1) so fast that it’s equivalent to the total-return approach or (2) not at all so that the portfolio predictably crashes. It would be interesting to see something in between where withdrawals are made from the more conservatively invested buckets during down markets and the rebalancing is delayed till the market starts to recover. This would require decision-rules with some thresholds for switching between market phases.

Rob,

I suppose ultimately it depends on what decision rules you try to create, but in general this will not help. If you really pursued this path – use cash when the market is down and then rebalance once the market has an up year, you would have used cash in 2000, 2001, and 2002, and then would have rebalanced in 2003 at a price point that was still lower than 2000 and 2001, and would have missed the rebalancing transaction in 2002 (which was the real opportunity to buy stocks) as well.

I’m sure you could retrofit and data mine some kind of decision rule that would work with the historical data set, but no particular reliability it would work going forward.

The point basically comes down to: yes, if you successfully time the market, the results will improve. Whether you can come up with a decision-rule in advance that will successfully time the market, of course, is more problematic. The realistic mid-point would be a valuation-based rule for making these allocation adjustments, which I’ve previously shown can be effective in the long run (though it will still not necessarily look good in any particular short-run period) – see http://www.kitces.com/blog/valuation-based-tactical-asset-allocation-in-retirement-and-the-impact-of-market-valuation-on-declining-and-rising-equity-glidepaths/

– Michael

Michael, thank you for keeping us informed. I’d like to know if there would be divergence between Total return and Buckets if you used a different asset allocated target risk fund for each bucket. The target risk funds held in each bucket would be automatically rebalancing and implicitly buying the relative underperforming asset class.

Thank you!

Michael,

I have a question. In the final chart above you compare wealth over time “with and without” rebalancing. The clear conclusion is that rebalancing greatly increases the value of the portfolio over time (as especially toward the end of the planning horizon). Yet, in your blog posts here (https://www.kitces.com/blog/is-rebalancing-supposed-to-enhance-returns-or-reduce-them/ and https://www.kitces.com/blog/is-passive-rebalancing-a-form-of-active-management/) you put forth the position that rebalancing only enhances returns if you get the timing right.

Should the above chart be assumed to include rebalancing with better than average timing or am I missing interpreting the point of this article?

Thanks in advance for all you do.

Regards,

Mike

Michael,

While I do agree with your comparison as described, it is limited to one type of bucket planning where you only sell into gains each year for income. I don’t believe in that strategy because you don’t take full advantage of compounding returns or momentum if you are pulling your gains from the positive portion of your portfolios each year for income. We deploy an approach of a now, soon, and later bucket.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/14202aea1757d66a84c54e1f3ae4fab19478d519a03d43a055afcf15d72d2a1f.jpg

The now bucket is the clients first year income left in cash at the bank for spending over the next 12 months. The soon bucket has 10 years worth of income invested in a guaranteed insurance product allowing us to withdrawal 10% of the initial deposit out as income plus a buffer account to act as an inflation hedge. Even if this insurance product only returns a 3% average return, the income stream would last 12-15 years before the account is spent down. The later bucket is mostly equities since we have a 12-15 year time horizon to let the portfolio ride before the now bucket and soon bucket is depleted. When we are about 5 years from depleting the soon bucket, we look at potentially taking gains from the later bucket to replenish the soon bucket. We start actively monitoring the soon bucket 5 years from depletion because that gives us plenty of time to wait out a correction before we would deplete the soon bucket. This is an abbreviated description, but you get the point. Have you looked at this type of Bucket Planning vs a total return strategy?

Thanks!

This article states that employing a bucket strategy, with rebalancing every year, is no better than just picking a static strategy as the rebalancing yearly will make them have exactly equal returns. However, the one key issue is: if employing a bucket strategy, how many years do you need to have on hand to cover yourself should the market take a downturn? In the same light, if one employs a static strategy, what is the highest % stocks that you can keep and still maintain enough bond $ to cover yourself should the market take a downturn right at the point of retirement? If you use too few years of bucket $ or too low of total bond $, then in a market downturn you may have to turn to utilizing your equity dollars sooner with no way to rebalance as you will have run out of your money in your non-equity portfolio. So, if one employs a static strategy, perhaps the best approach is to keep just enough money in your bond portfolio to cover your living expenses should the market take a downturn. But how many years should one safely keep?

Michael,

Excellent article. There is a fourth (happy) scenario that appears to be missing, namely, what to do when BOTH Bucket 2 and Bucket 3 are UP? Do you sell them BOTH at a gain? Or do you let them continue to grow, in which case you must pull from Bucket 2 to fill Bucket 1? And is the goal then to keep your original balance intact by taking gains off the table? But you then miss out on reinvesting/compounding gains in Bucket 3, etc. etc. Thanks in advance for your insights.

Love this work on bucketing as well as your prior articles on rebalancing, including your prior piece on banded rebalancing.

I’m curious what your thoughts are about the fact that systematic rebalancing increases maximum portfolio drawdowns during multi-year declines like the great depression or, dog forbid, a Japan like equity debacle? Your own work shows that the main benefit of rebalancing is not to increase returns but to lower risk somewhat. So if you pair that reality against the fact that in the VERY worst scenarios, rebalancing increases risk, it’s no bueno yes? In a race to the bottom, banded rebalancing could be even more treacherous. Sorry for being a buzz killer here.

F

Michael, wich software you use to model the withdrawals?

Thanks