Executive Summary

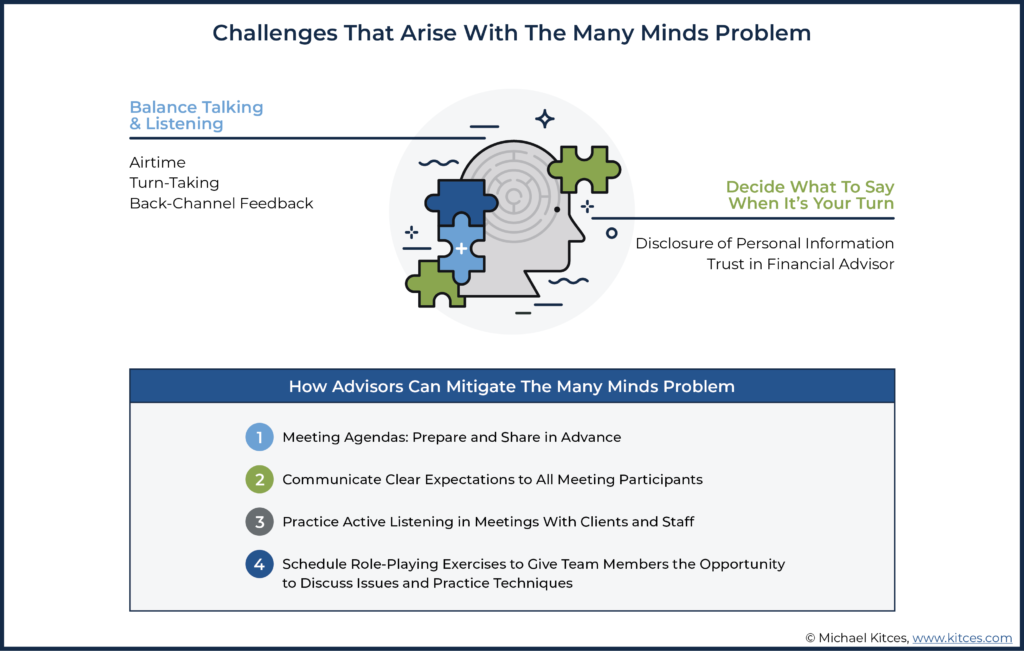

Many advisory firms are building advisory teams with the hopes of sharing the workload and increasing client satisfaction. However, there are inherent challenges faced by teams, which consist of a group of "Many Minds" whose conversational mechanics are increasingly complicated by the growing number of participants, specifically when it comes to effective team communication. In fact, Harvard researchers studying how communication changed between two-person ‘dyad’ conversations and multi-person group conversations found that group communication is inherently more complex (and more problematic, as expected) because of two primary issues: 1) the ambiguity that arises regarding how and when to talk or listen, and 2) what to say (or not to say) when it is a person’s turn to speak.

When it comes to assessing how and when to talk and listen in a group conversation, there are three important considerations that will help an advisory team successfully communicate with clients: airtime (i.e., the time a person is given to speak during the meeting) is shared, typically unequally, among the meeting participants; taking turns to speak can be much more confusing in groups than between two people, as whose turn it is to speak when someone else is finished talking can often be very ambiguous; and back-channel feedback provides cues – both non-verbal (e.g., head nods, hand gestures, etc.) and verbal (e.g., saying 'yes', 'mmm-hmm', 'oh', etc.) – from listeners that let the speaker (and other participants) know they are being heard, but it is typically more limited in group conversations (as we may engage less like a participant and more like a staid audience).

Deciding what to say and how much information to offer to an advisory team can be an especially difficult process for a client, who must evaluate whether and how much to disclose personal and sensitive information… the specific type of information required during a financial planning meeting. The situation can be worse, too, if the client prefers working with a single advisor and is not yet comfortable sharing sensitive personal details with their entire advisory team.

Some tools that advisory teams can consider to optimize client communication and to develop trust include preparing agendas for all meetings that are sent to participants in advance with the aim to encourage thoughtful discussion by all who attend; setting clear expectations to facilitate a better balance between the client and advisory team members with respect to distributing conversation airtime; using active listening techniques that involve fully concentrating, understanding, and responding to what the person they’re talking to says; and organizing role-playing exercises for team members to practice communicating and focusing on the dynamics between participants.

Ultimately, while advisory teams are commonly faced with "Many Minds" issues that can make it difficult to communicate effectively with clients (and to keep them happy!), there are several tools (using meeting agendas proactively to spark engagement and develop rapport, setting clear expectations, active listening, and role-playing activities for advisory team members) that can help to overcome these challenges. Because despite the challenges that all teams face in working to communicate better, the benefits of working in a well-developed and well-trained team can far outweigh the drawbacks as, in the end, team members can work to keep clients happy while supporting each other in the process!

Two Heads Might Be Better Than One, But Three (Or More) Heads Are No Fun – How The Many Minds Problem Can Negatively Impact Group Communication

The concept of “Many Minds” communication comes to us from Harvard researchers Gus Cooney, Adam Mastroianni, Nicole Abi-Esber, and Alison Wood Brooks, who were interested in how and why communication changes in a multi-person group setting when compared to a two-person 'dyad' conversation.

What they found is a phenomenon they called the “Many Minds” problem with 3+ person groups, where conversation and communication become less effective once the situation moves beyond a 2-person dyad, as a result of two central issues: 1) how and when we decide to talk versus listen; and 2) how we figure out what to say (or not to say) when it is our turn.

Assessing How and When To Talk And Listen In A Brainstorming Group

When it comes to assessing how and when to talk or listen in a group setting, there are three important considerations that explicitly or implicitly run through our heads: airtime, taking turns, and providing listener feedback through ‘back-channel’ cues.

Airtime Gives Speakers The Floor And Offers Listeners The Space To Consider Their Own Turn To Speak

Airtime is exactly what you would imagine; it is how long the speaker holds the floor. And in a group, this matters more because as the size of the group increases, the potential airtime available for each person decreases. After all, speaking half the time in a dyad is just your fair share of the conversation; speaking 50% of the time in a group of 10 is clearly hogging the air time.

And in practice, it turns out that group members really don’t tend to share airtime equally among themselves, and there are often just a few people doing most of the speaking. Though this isn’t necessarily a negative and is often explained simply by the personality and trait dominance characteristics of the group members, such as extraversion and introversion (i.e., introverts tend to not want to speak up in large group settings anyway), as well as gender composition and leadership roles.

However, the challenge in the group setting is not merely that some people tend to talk more than others – where a 'group conversation' ends out, according to the Harvard Many Minds researchers, as a 'two-person conversation with an audience'. Because the obvious flipside to the airtime coin is to ask what the other people do when they are not talking? Are they listening intently, are they zoning out, are they thinking about how they feel left out, or are they thinking about what they intend to say next?

The answer, according to the research: It turns out that most people are not actually listening; instead, they are thinking of what they want to say next!

Why Taking Turns In Group Conversations Can Be Difficult

The second consideration to examine how and when we decide to talk in a group conversation involves taking turns.

As with the back-and-forth nature of a two-person conversation, there are many obvious signs that indicate when one person is done talking and when it is the other’s turn to start talking (e.g., hand gestures, questions, silence).

However, in a group setting, the back-and-forth direction of the conversation is less clear, and it is often ambiguous to identify whose turn it is to talk. For example, when meeting with a client couple, does the advisor signal whose turn it is to speak next? If so, how is this done? And did the decision to pick one member of the couple to talk first just offend the other?

Listener Feedback Offers Important Cues To The Speaker And Is Effective In Establishing Rapport

Back-channel feedback is the third factor to consider when assessing how and when to talk in a group setting. This involves examining body gestures (e.g., head nods) and or simple speech cues (e.g., 'uh-huh', 'yes', 'hmmm') that are made to the speaker to let them know we are listening.

Back channeling, although simple in practice, is really an important component of group conversations. Imagine how weird it would be to have a conversation with someone who does not look at or respond to you, letting you know that they are following along or engaging with you (although if you have children, it may not be that weird to imagine!).

For example, imagine being on a date and, instead of listening to you, the person across the table is distracted by their phone, their watch, another table across the restaurant, or, perhaps weirdest, just staring blankly at you with no expression – nothing. Even if they really are listening, it doesn’t feel like a fulfilling conversation!

In group settings, back-channel feedback tends to decrease. In fact, researchers found that as the size of the group increases, the number of people providing back-channel feedback decreases… even though there are technically more people available to provide it!

The researchers describe this phenomenon as a diffusion of responsibility; similar to the bystander effect, this behavior involves each member of the group thinking that someone else is responsible for providing feedback, which, when everyone has the same thought, results in no feedback being given by anyone at all!

For financial advisors working with couples or groups, this effect can be detrimental to the relationship, as research has shown that this lack of back-and-forth communication can actually decrease rapport. Which makes sense, as rapport will inevitably break down when you do not feel that people are paying attention when you are talking.

Nerd Note:

While many of the issues discussed in this article focus on in-person group communication, the reality today is that conversations are taking place more frequently in a virtual environment, which involves these Many Minds issues as well (and likely even other issues not discussed in this article). For instance, back-channel signaling becomes even more complex in a virtual environment where we have few to no body language cues (maybe not even a floating head to see nodding, if videos are not in use) and many times, using the mute feature, speakers do not hear any of the verbal cues (e.g., 'uh-huhs', 'hmms', etc.) that indicate people are paying attention. This could also explain why recent articles have found that in virtual group meetings, there tends to be a greater prevalence for participants to ‘zone out’.

Deciding What To Say And How Much Information To Disclose In A Group Conversation

The second issue brought about by the Many Minds phenomenon is what to say (or not to say). This is perhaps the most unnerving/problematic issue as it pertains to financial advisors who work in groups and meet with clients as a team (e.g., lead advisor, associate advisor, and a coupled client), and its impact is likely heightened because of the nature of the work that financial advisors do. As when we are in groups, we are less likely to feel inclined to disclose personal information – and this is the very information that financial advisors need to help their clients.

To examine this issue more deeply, we can look at it from two perspectives. The first is to consider the actual problem, and that is the fact that disclosing personal information is hard (and even harder in group settings). The second is how the work of financial advisors (and how the meeting process itself occurs) can make it more difficult for clients to openly communicate with and develop trust in their advisors, especially when clients meet with a team of advisors.

Moreover, being open feels risky (and as humans, we tend to be risk-averse); although there is research that indicates being vulnerable can be valuable for establishing a genuine connection in relationships, this does not make it any easier to do. And being vulnerable in front of a group of people is even more difficult and can even result in confusing situations.

For example, there could be information that is okay to share with A but perhaps not okay to share with B. So, what does a person do if both A and B are in the room?

Example 1: Sarah, the senior advisor, and Adam, the associate advisor, are meeting with their client, Carl. Carl has worked with Sarah for a long time, but this is only the second time he has been in a meeting with Adam.

Moreover, Carl and Sarah have been through a lot together – in fact, when Carl was diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder a few years ago, Sarah was someone Carl told about his diagnosis because he wanted his financial planning engagement to help protect him from himself.

However, Carl feels very uncomfortable about disclosing some recent financial activity during a manic episode with Adam, the associate advisor, in the room.

In addition to the confusion that can arise from having to disclose uncomfortably personal and sensitive information, there may also be conflicting issues that involve goals and intentions (for both the client and the advisor) within a meeting.

Example 2: Adam, the associate advisor newly hired to the firm, wants to impress Sarah, the senior advisor. At the same time, Adam wants to connect with Carl, the client.

During the meeting, Adam inadvertently interrupts the dialog that Sarah and Carl are engaging in, in an attempt to look smart in front of both of them.

He is eager to answer questions and be helpful, but his behavior (interrupting an ongoing conversation) only serves to embarrass Sarah and offend Carl.

An additional issue with group communication is that when something goes wrong, it can be a lot harder to fix than if the problem involved only one other person.

For example, if a mistake is made in a group setting, more people will hear the mistake (bummer number one), and with more people involved (with less airtime generally allocated to members in the group), there may be less of an opportunity to rectify the mistake (bummer number two).

Furthermore, in a group setting, there is generally less feedback and turn-taking (simply because it is difficult for people to understand how to take turns and give feedback in a group), which can result in difficulty finding appropriate solutions to the mistake with other members of the group (bummer number three).

Example 3: Carl the Client pushes past the discomfort he feels from having the new associate advisor, Adam, join their meeting, and he discloses some recent spending.

As he is talking, Sarah and Adam are listening, displaying good back-channel feedback. However, partway through Carl’s review of his spending, Adam lets out an inadvertent, 'oh no'.

Carl is now super-uncomfortable and goes silent. Sarah feels awful and is now talking rapidly in an attempt to save face. Adam is just sort of stuck with his foot in his mouth.

Given the group dynamics, Adam does not necessarily feel he has the time or place to tell Carl what was going on in his mind. Even though the reality is that, unbeknownst to Carl and Sarah, Adam has a family member that also struggles with spending during manic episodes.

Adam had let out the 'oh no' because he was actually empathizing with Carl, but at the moment, with other people in the room, this comes across as judgmental and not what it truly was – empathy. And in a group setting, it’s even harder for Adam to now try to interject, explain the situation… and, in turn, disclose his personal family situation that he may not have been comfortable sharing with a co-worker in a group setting!

The second perspective to consider with respect to the 'what to say (or not)' issue is why financial advisors and their clients may struggle to establish open lines of communication in the first place: because disclosing personal information is difficult.

Essentially, the average individual is really uncomfortable talking about their finances. Money is often a point of contention. Money means more than just money. Money is something clients often feel insecure about because of their lack of knowledge around it. And money issues can sometimes feel shameful. Simply put, clients are not likely primed to disclose personal money issues, and will likely have an even harder time with more people in the room.

In other words, while talking in groups, in general, is hard, talking about money in a group… is even harder.

How The Many Minds Problem Impacts The Planning Relationship

For many financial advisory firms, advisor teams are often organized to work and meet with clients, as team members can efficiently share the workload, provide support to senior advisors assigned to the team, and offer clients a vision of the firm’s unified and more expansive team efforts. Accordingly, it is important for teams to recognize how the more complex conversational mechanics inherent in groups can potentially lead to communication breakdowns, and that these Many Minds challenges must be overcome to reduce the risk of compromising client satisfaction.

For instance, research from the medical field that studied the impact of teams on client/patient satisfaction found that teams very clearly do not naturally bring about client satisfaction. Said another way, just because one has a team does not mean that client satisfaction increases – team benefits are only mediated by effective communication within the team, which can be very hard to achieve. In fact, a couple of meta-analyses specifically investigating medical teams show that teams had a positive impact on satisfaction only about 57% of the time – nearly the same odds as flipping a coin!

Despite the results of these studies showing a relatively poor correlation between teams and client/patient satisfaction, it is still interesting to identify other relevant points made by these studies pertaining to how we think about financial planning.

And this makes sense, or would be what we would expect to find given the Many Minds research – who makes up the team (who does the talking and listening) and how the team operates (what are they saying or not saying) are key factors in the model. In many ways, the finding that teams do little to improve client satisfaction simply reasserts the importance of the Many Minds problem.

Teams Don’t Improve Communication, And Communication Is What Matters To Clients

It is clear that teams, especially those that struggle with common Many Minds problems, are not always great at communication, and it is a lack of communication that is often used to negate the idea that teams lead to higher client satisfaction (e.g., through Medical Research and Chicken versus Egg arguments).

It is also very clear from research in financial planning that communication is what clients actually care about when it comes to satisfaction!

Example 4: Sarah is a senior advisor and works with two associate advisors, Alicia and Aaron. They provide varied services to a large client, Carol and Chuck Moneymaker.

During the meeting with all three advisors, the Moneymakers are frustrated because Sarah, Alicia, and Aaron are doing more talking amongst themselves – asking about the paperwork that one advisor received and discussing administrative tasks that the firm needs to complete – than they are talking to Carol and Chuck about their financial planning needs.

Carol and Chuck both feel left out of their own meeting!

Study after study has shown that poor communication is a deal-breaker for clients. A recent report from E-Trade, using data from a 2014 Spectrum Group study, shows that clients often leave their advisors because of poor communication.

Another study from 2013 by Financial Advisor Magazine surveyed 1,375 advisors and found that the number one reason clients left was a failure to communicate on a timely basis. And, especially relevant to the Many Minds problem, poor communication doesn’t just equate to a lack of communication, misunderstandings are also a hallmark of poor communication.

Example 5: It has been two weeks since the meeting between the advisors (senior advisor Sarah, and associate advisors Alicia and Aaron) and the Moneymakers. The meeting had ended with a number of follow-up tasks, and the advisors promised that someone from the team would be in touch in the next few days.

However, Carol and Chuck Moneymaker have received neither an email nor a phone call about progress on any follow-up tasks, nor have they been told what might be needed from them. Carol and Chuck are again frustrated.

Chuck decides to call. After speaking with Aaron, Chuck uncovers that there was a breakdown in communication between the advisors. Everyone seemed to have thought that someone else was responsible for the next steps, which resulted in nothing getting done.

The firm had failed to respond to the Moneymakers on a timely basis, and there was clearly a misunderstanding in terms of communicating deadlines and responsibility.

The Moneymakers are thinking about moving to a different firm because communication has been so poor.

Now, if you are thinking, “No way! I have for sure read that teams bring about client satisfaction!” I hear you. Teams are often thought to bring about client satisfaction, but this conclusion is likely flawed or at least does not reflect the whole truth, given the research we have in financial planning (which, unlike medical research, has never actually focused specifically on this question).

For example, advisor research claiming that teams improve client satisfaction is generally insufficient because most fail to use an experimental set-up to compare satisfaction levels of clients working with teams (versus clients working with solo service providers), and few even get around to asking what the client thinks of the team experience!

Instead, the studies in this area usually ask advisors if they think their clients are happier with a team experience. And perhaps the advisors who believe that their clients are happier are right. But that’s probably also what the doctors thought… until the research found that from the client’s perspective, it was actually a coin flip on the benefits of the team, and exactly how that team experience was composed and delivered.

In other words, advisors may simply believe (or want to believe) that their efforts of developing a team have paid off with a positive impact on the client. But as the data suggests, just having a team isn’t enough; at best, it takes conscious effort to consider how, exactly, that team is composed and being executed.

Another way that the idea that teams equal client satisfaction is erroneously supported is when assets from a team-supported client are compared to those from a client working only with a solo advisor. This approach, however, does not necessarily establish causality between teams and client satisfaction; rather, it is a chicken vs. egg argument.

For instance, do larger clients have a tendency to pick advisory teams to begin with (which would result in more assets for the firm)? And did the client come to the firm because it has larger teams, or was the firm compelled to create a team simply because the successful lead advisor reached capacity and had to hire more advisors to help (where clients may now have less satisfaction because they no longer get to interact as much with that original highly-effective lead advisor)?

Or perhaps a team includes a range of professionals with different areas of expertise (e.g., CFP, lawyer, CPA, financial therapist, etc.). In this situation, clients may be inclined to hand over more assets for the firm to manage because they feel they might more fully leverage the expert advice available to them. Either way, this does not prove that clients are actually more satisfied with the team. As while teams with more expertise or a deeper bench may be getting clients because they are better able to establish credibility, it does not mean they can improve client satisfaction any better than a solo advisor!

And for some clients, working with a team (even if they need the team) is not really what they want. It is not uncommon for clients to prefer working with a single point-person within the team – they don’t want to talk to a team or, worse, they don’t want to have to explain the same issue to multiple people on a team. And that is what at least one medical research study showed, that patients with teams still prefer to have just one point of contact.

How Advisors Can Lessen The Many Minds Problem To Prevent Communication Breakdowns In Their Teams

In order to deal with the varied issues surrounding communication breakdowns in teams, it is helpful to remember that the two main issues relevant to the Many Minds problem are 1) balancing talking and listening, and 2) deciding what to say (or not to say) when it is your turn to talk.

A seemingly simple and relatively straightforward solution for advisors to ensure that there is a good balance between talking and listening during client meetings, and internally amongst staff, is to prepare (and use!) agendas, identify expectations, practice active listening skills, and establish clear roles. While these practices may seem simple, consistently implementing them is certainly easier said than done.

Agendas Can Enhance The Experience and Utility of Client (and Staff) Meetings

While it might be easy enough to actually create a meeting agenda, this extra step can be… well… an extra step. And given that financial advisors tend to be very busy people, it can be very difficult to manage even just this extra step, especially if it’s not something that is normally done.

However, meeting agendas are a very important step, and by creating a relatively uniform template for each type of meeting, the agenda, once implemented, can be easy to use again and again with minimal effort to prepare a new one for each meeting.

For example, a simple meeting agenda structure might include:

- Open-ended updates.

- What is new in the client’s life or situation from the last time you spoke?

- Preferably these would use statements – “Tell me, since the last time we spoke, what has changed with X.”

- What is new in the client’s life or situation from the last time you spoke?

- Financial updates.

- What news, updates, or review needs to be provided to the client in relation to their financial plan?

- List these out on the agenda so that clients may prepare for the news with questions or thoughts.

- What news, updates, or review needs to be provided to the client in relation to their financial plan?

- Important topics.

- What topics or issues does the advisor or client wish to discuss or solve by the end of the meeting?

- List your questions ahead of time.

- List the discussion topics ahead of time.

- Solicit questions or topics from clients ahead of time, if possible.

- Include these items on the agenda.

- What topics or issues does the advisor or client wish to discuss or solve by the end of the meeting?

- Planning.

- This is where the client and advisor’s important topics are set to an action plan.

- Follow-up.

- Discuss any follow-up items and how and when the client will be contacted to review any next steps. This may just involve scheduling the next meeting, but it might also include numerous follow-up steps that need to take place to address a financial concern.

This style of meeting agenda can be used not just as a client meeting agenda, but also as an internal meeting agenda.

The goal of the agenda (internal or external) is to set the schedule for the meeting, but perhaps more importantly, it can serve to prime those who will be in attendance to start thinking about the discussion points in advance, which can serve three purposes:

- Participants will likely have more to share in the meeting because they have something actually prepared to share in advance;

- Everyone will have a chance to formulate their own unbiased, unique, and valuable thoughts, thus minimizing ‘group think’; and

- People will have time to think about what they want to say in advance before the meeting, which will allow them to use the meeting time to listen to others and what they have to say.

Thus, meeting agendas would ideally be shared with all participants, internally and externally, a few days before the meeting. The agenda should provide enough information to get meeting attendees thinking and brainstorming, but it does not necessarily need to be so detailed that the agenda takes a very long time to write and could essentially be used in place of the meeting.

And sending the agenda out in lieu of actually holding the meeting is a critical point to consider. Meetings are supposed to be a time to brainstorm and create connections. They are not just in-person to-do lists. Even if the meeting is about a lot of to-dos, that is okay. If the agenda is set out beforehand, the meeting can serve to cultivate buy-in from those responsible for the to-do tasks and to co-develop an action plan that works for the client.

Advisors can use the agenda-creation process as an opportunity to plan fruitful and collaborative discussions, not just as a way to practice relaying information.

Clarifying Expectations For Meetings In Advance Can Help To Enhance Discussions

Clear expectations are another tool to ensure a good balance between talking and listening is maintained. When setting expectations, let nothing be implied.

For example, simply providing an agenda does not necessarily signal to clients and other meeting participants that they are being asked to prepare something. It is important to clarify that meeting participants should review the agenda and actively think about the key discussion points outlined. This is especially relevant if creating agendas is a new practice or, for firms already using agendas, if the agendas are not being used to create dialog and discussion.

To address the 'what-do-I-say-when-it-is-my-turn' issue, advisors can ask clients and other meeting attendees to come prepared with answers, ideas, comments, and feelings before the meeting begins. Because again, pre-planning questions and responses will likely help cut down on individuals unable to focus on meeting dialog because they are preoccupied thinking of their own responses during the meeting.

Thinking of discussion points before the meeting might also result in more participation from all parties when everyone is encouraged to attend the meeting prepared to share.

Active Listening Helps Advisors Identify Issues That May Be Worrying Their Clients While Strengthening Trust and Improving Rapport

Because one of the major problems created by Many Minds (like most communication challenges) is that there is not enough listening, it is probably no surprise that the Many Minds problem can be helped by active listening. However, again, this is one of those things that is much easier said than done.

Active listening is a practice often used in counseling and conflict resolution that involves fully concentrating, understanding, and responding to what the client is saying. When using active listening with a client, the financial advisor gives their full attention to the client and makes sure to understand precisely what the client is trying to say. To ensure full understanding, the advisor will repeat what they believe they heard to confirm that they understand what the client is trying to get across.

The following examples illustrate good and bad meeting outcomes and show how active listening can be very useful in effective meeting communication between the advisor and client.

Example 6: After experiencing the disappointment and frustration with their advisors’ lack of communication following their last meeting, Carol and Chuck Moneymaker are giving Sarah, their senior advisor, and her team another chance.

Neither Carol nor Chuck want to deal with finding another advisor, but the truth is that they are not really satisfied with what they have either. Carol and Chuck have decided, unbeknownst to Sarah and her team, that this is their last rodeo.

The Moneymakers are going to explain their grievances to Sarah and her team and give the team one more shot to have an effective meeting and follow-up. If it goes well, they will stay. If it does not go so well, they will walk.

During the meeting, the dialog takes place as follows:

Sarah: Welcome back, Carol and Chuck, how are you today?

Chuck: Actually, not so great.

Sarah: Oh, I am sorry to hear that, but I think I have some news that will brighten your day.

Chuck: Oh, um…well, okay, then. What would you like to tell us?

Sarah: Aaron, you all know Aaron, our associate advisor? Well, he was finally able to take a look at your tax situation, and he has some suggestions for how we might improve your overall tax bill. He will be in later to explain it to you.

[Sarah gestures to the receptionist to ask Aaron to join the meeting]

Chuck: Nice. I look forward to what he has to say. While we wait for him, I would like to discuss some concerns that Carol and I have.

Sarah: Sure, of course.

Chuck: I know you are all doing a lot for us and that there is a lot of expertise supporting us, but Carol and I do not really feel a part of the team, and it seems like we are struggling with how to communicate with the advisory team.

Sarah: Okay, I understand. You are unhappy about how long some of the paperwork took from our last meeting. Totally understandable. I don’t like operating that way either.

[Aaron enters the room.]

Sarah [to Aaron]: Great, welcome, Aaron. The Moneymakers are excited to hear your presentation.

Sarah [to the Moneymakers]: You are really going to like this! Aaron has found a way to save you $10k. We will do better on follow-up this time around.

In this example, Sarah was not doing anything wrong, per se. She took responsibility for the mistake and probably really wants to repair and improve the relationship with the Moneymakers.

However, Sarah was not an active listener at all in the above example. She heard the client express that something was wrong, but she didn’t actually listen to the problem and may have come across to the client as rather flippant.

Let’s now compare and contrast with a meeting where active listening is employed.

Example 7: Instead of the meeting dialog as outlined above, the conversation goes more like this:

Sarah: Welcome back, Carol and Chuck! Per the agenda we sent last week, tell me what is most important to you today.

Chuck: Hi, Sarah, yes, nice to see you. Carol and I want to talk about some concerns we have.

Sarah: Concerns, okay. Describe these concerns for me.

Chuck: I’m not exactly sure how to say this, but Carol and I do not really feel a part of the team. I know you are all doing a lot for us and that there is a lot of expertise supporting us, but it also seems like we are struggling with how to communicate with your team.

Sarah: Thank you for bringing this to the discussion. Please tell me more about when you say you don’t feel a part of the team.

Carol: Well, for one thing, no one ever asks me how I feel or what I think. Everyone just talks to Chuck. I feel like an audience member in my own meeting!

Chuck: Yeah, and well…I know there is a lot that you do for us, but I don’t feel like we ever really discuss what our options are. It just feels like by the time we get to the meeting, your team is already in agreement about what needs to happen next. Which I guess is better than disagreement, but I do not ever really feel included in that process.

Sarah: Thank you both for this honest feedback. I really appreciate it. If you don’t mind, I would like to repeat back to you what I have heard you say, so that I can be sure I am understanding you and please correct me if I do not get it right…

Sarah [to Carol]: Carol, I hear you saying that you feel we do not include you. And if I may, you want to be included because you have your own ideas and information to share.

Carol: Yes, that’s right. I do have ideas that I want to share and questions that I want to be answered, which are not always the same ideas or questions as those of Chuck. I want to be treated as an equal partner and given equal airtime to voice my thoughts as that of my husband.

Sarah [to Chuck]: Chuck, I hear you say you want to be more involved in the details. And, again, if I may, you want to take on a greater role doing some of these tasks.

Chuck: Yes, and no. Yes, I do want to be more involved in the details and understand who is doing what and when. However, I do not actually need to be the one doing certain things. I still trust your team to implement. I just want to know who is implementing what so that if I have questions, I know who to turn to about them.

Sarah: Carol and Chuck, thank you again for your honest feedback. I will discuss your concerns with the team. We will definitely include you in more of the decision-making process, and the team will communicate with you more proactively in the future. Speaking of the other team members, you all remember Aaron, our associate advisor? Well, he was finally able to take a look at your tax situation, and he has some suggestions for how we might improve your overall tax bill. He will be in later to explain it to you.

[Sarah gestures to the receptionist to ask Aaron to join the meeting]

Sarah: While we wait for Aaron to join us, tell me, are there any other concerns you’d like to share with me?

Carol: No, but we appreciate your listening and being responsive to our feedback.

Sarah: Yes, of course. If you do ever have any questions or other concerns, you can always reach out to me or to one of the associate advisors on our team, Alicia and Aaron.

[Aaron enters the room.]

Sarah [to Aaron]: Great, welcome, Aaron. The Moneymakers are excited to hear your presentation.

Sarah [to the Moneymakers}: You are really going to like this! Aaron has found a way to save you $10k. And we will explain in greater detail for you, Chuck, how this is going to happen. And Carol, please interrupt as questions come to you.

The main difference between Examples 6 and 7 is that, in Example 7, Sarah, the senior advisor, uses active listening to learn about the client’s concerns. Through her dialogue with the client, Sarah learns how Carol and Chuck are impacted by poor communication and has better ideas for how to address their concerns.

In contrast, Sarah is simply hearing the client speak in Example 6. She assumed she already knew why Carol and Chuck were upset and had the intention of rectifying the situation. While Sarah cares about the client and believes that everyone understands that bad communication stinks, her strategy is to acknowledge and move forward.

Specific to this Chuck and Carol problem, by engaging in active listening, Sarah addressed one of the Moneymaker’s concerns by making Chuck and Carol feel like they were an actual part of the team when she spoke to both of them about their needs.

Through thoughtful follow-up and clarifying questions and statements (two key features of active listening), Sarah spent more time listening because the clients spent more time talking – and because she had to focus on just listening in order to repeat what she thought the clients were saying.

Role-Playing Offers Teams The Opportunity To Practice Communication Skills And To Mitigate The Many Minds Problem

The final suggestion for how to address the problems associated with the Many Minds problem is practicing through role-playing. Yep, role play.

In practice, role-playing is not natural for many of us and may feel outright weird and uncomfortable. But the good news is that there are ways to make this less awkward!

So first, the argument(s) for why role-playing matters. Active-listening (as established) takes practice, and being a team takes practice. Role-playing offers financial advisors and other team members an opportunity to practice (and improve) both skills.

For example, as teams grow, change, and expand, different team members may be unsure of how their roles evolve with those changes or the importance of the perspective that they provide (and this includes the client!).

Basically, simply because Sarah and Aaron will eventually develop a rhythm of working together, what happens when Aaron needs to work with just Alicia (the other associate), or when Aaron is no longer an associate advisor and now has his own clients and a new associate advisor to train? Teams are in constant flux, and role-playing exercises offer a perfect opportunity to practice how new roles will play out – both at an individual level and at a team-based level.

So what can you do to practice these skills through role-playing?

Advisors can start by setting the expectations. For example, set a standing, agenda-based meeting with your team. This meeting could be every other week for 1 hour to discuss a recent client issue. The client issue can be chosen and briefly outlined in an email to the team the week before the meeting takes place by a new person each time so that everyone comes to the meeting ready to discuss (just like client meeting agendas discussed above).

The meeting then begins with each person sharing three bullet points that occurred to them about the presenting issue – with the over-arching goal of giving everyone some airtime. As each person states their three bullet points, the person to their left then needs to practice active listening skills by summarizing and repeating back to the person that just spoke what they heard them say. And as active listening goes, any clarifications that need to be made can be made.

Once everyone has shared and has had the opportunity to practice active listening, getting all concerns out in the open, the team can brainstorm solutions to the issue, or just discuss their ideas and thoughts. The meeting may then conclude with some agreed-upon action items, or can simply conclude with greater clarity and understanding of a topic, issue, or process.

Now that we know what to do and have an example of how role-playing might be implemented, let’s consider what we can do to make these exercises feel less odd.

- Acknowledge that, at first, these activities will feel awkward for most participants. You will feel like a parrot when you start practicing active listening. Discuss these feelings with your group and learn from each other. Lean on your peers and team members for how they are getting more comfortable.

- Make it about learning. It is okay to screw up, and in fact, better to screw up with teammates when practicing than in front of a client. No one does this right the first time (maybe even the first 20 times), so do not assume that becoming better listeners and working as a team is an easy thing to do.

- Share feedback. At the end of the meeting, before everyone breaks, rate or discuss the meeting. What was helpful, what was not, and what did you learn. If the meeting didn’t go well, know why it didn’t. If your teammate is still struggling, ask what you might be able to do to make it better next time. (Bonus: this last part requires active-listening and can give you insight on how to be a better team member!)

In closing, a point I would like to make is that I still think teams can be really beneficial. Teams help with efficiency, create opportunities for training, and support advisors with their workloads (and thereby keeping them from burning out).

While this article was not meant to suggest that teams should end, it was meant to reveal some of the potential weaknesses of teams so that advisors can be aware of them and proactively address those weaknesses so that advisors (and clients) can enjoy the benefits of teamwork.