Executive Summary

It’s difficult to give financial advice to others if you don’t have your own financial house in order, first; not that anyone – including financial planners – is “perfect” when it comes to their own money, but in the end, if financial advisors can’t even follow the advice and go through the process themselves, it suggests that, at the least, there’s room for improvement in the advice itself or how it’s delivered.

In fact, arguably, one of the best ways for financial advisors to really understand what it takes to give good financial advice is to better understand their own financial challenges and what they need to change to improve their own situation… akin to how therapists become better at providing therapy by going through the process themselves.

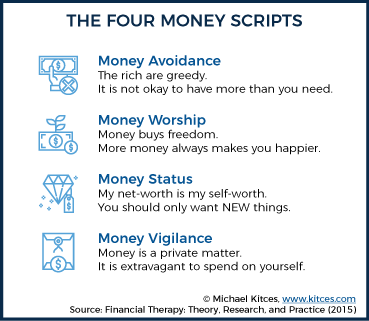

Money exercises that financial advisors can go through (by themselves, perhaps for future use with clients as well) include the Money Egg (sketching out some of your earliest money memories, reflecting on whether they were positive and negative, and considering how those embedded money memories may be impacting your decisions today), assessing your Money Scripts (do you tend towards Money Vigilance, Money Status, Money Worship, or Money Avoidance?), and considering how your prior money experiences may have created Money Narratives that now impact (or even burden) your everyday decisions (e.g., my advisory firm is a reflection of my self-worth, so I have to keep growing my firm to grow my status… even if I really don’t financially need a larger firm at all!).

Ultimately, many (or even most) financial advisors may feel uncomfortable doing such deep self-reflection on their own financial situation and may find it awkward and intimidating to get help and outside advice around their own money challenges. Yet at the end, when clients are asked to do the same things themselves with a financial advisor, arguably going through the process as an advisor provides a good perspective (and perhaps even empathy-building) for the stress and emotional turmoil that clients may be feeling in the financial planning process as well!

Surprise, Margaret Atwood (yep, the author of the super famous dystopia, The Handmaid's Tale) wrote a book on debt: Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth.

As Atwood describes it, Payback is a literary history of debt (and a crazy interesting one at that). But in many ways, it is also part-memoir and part-self-discovery of her own relationship with money and debt… and excerpts from her book can provide remarkably salient lessons for anyone (but rest assured, we won’t share any spoilers here).

In point of fact, self-discovery/introspection/self-examination arguably is a good idea for all financial planners. In therapeutic training, it is common; you can’t really be all that great of a therapist if you don’t do a little of your own internal work first. Which may be true for financial planners, too.

After all, as Atwood herself so poignantly pens, “Writers write about what worries them… Also about what puzzles them… The subject of Payback is one of the most worrisome and puzzlingly things I know: that particular nexus where money, narrative or story, and religious belief intersect, often with explosive force” (p. 2).

Moreover, using Atwood’s own journey and questions as a backdrop for investigation and self-reflection – this blog will also introduce financial psychology and financial therapy tools, like money scripts (and the money disorders that can tie to them) and money eggs, to assist financial planners in doing a little bit of their own self-reflection work. Because, again, you can develop a deeper sense of empathy and understanding of your clients by reflecting on your own financial journey and challenges, too.

Money Memories and The Money Egg Exercise

We would probably all agree that our memories have long-lasting impressions on us. Yet, it is rare that we actually take the time to sit down and think about what the long-lasting impression is, where it came from, and now, potentially understanding it through adult eyes, how particular memories have power over us today, or how they may be manifesting themselves into our belief system and behaviors.

Consider the following excerpt from Margaret Atwood, as she recalls an early money memory…

“The first job paid 25 cents an hour – a fortune! – and consisted of wheeling a baby around in the snow…It was at this time that each penny came to be worth the same as every other penny…when I’d accumulated a dangerous amount of the stuff (money) – say, a dollar – I would deposit it in the bank… Every once in a while an extra sum would appear… This, I was told, was called interest… I didn’t understand this either. It was certainly interesting to me that I had extra money – that must be why it was called interest – but I knew I hadn’t actually earned it.” (p. 4-5)

Money and our financial systems can be really strange things as adults, let alone as children. In Atwood’s memory, both her word choice (e.g. fortune and dangerous) and her logic (e.g. each penny was worth the same as every other penny, and it is “interest” because it is interesting to find yourself with extra money) tell us something about how she remembers money and experienced having earned money – which appears to have ultimately ended up being tied to Atwood’s later revelations in the book about fairness, and the aptly named title to her book, Payback.

Financial advisors can similarly explore their own financial history with the “Money Egg” exercise, getting in touch with some past (financial) memories, and connecting them to themes in your current life. The Money Egg was developed in collaboration between financial psychologists, Drs. Ted and Brad Klontz, and a financial therapist and financial practitioner, Rick Kahler, by adapting a widely-known therapeutic tool known as the Trauma Egg. The Money Egg process enables people to open up to emotions that may be present in their memories, and process through what has probably not been thought through or thought about in great detail before.

To complete the Money Egg process, you will just need a large-ish piece of paper (8.5x11 is okay, but bigger is better) and some drawing utensils (pen, pencil, marker, crayons). (You can try now, or find a quiet time and space where you won’t feel crowded or rushed if you don’t have time at the moment.)

The six steps of the Money Egg process are:

Step One: Draw a large egg onto your paper, using your non-dominant hand. (Using the non-dominant hand may seem a little odd at first, but it is important for two reasons: 1) it will again help you to not pass judgment, or get too caught up in the “art” because it is going to look funny anyway using your non-dominant hand, and 2) using your non-dominant hand gives you access to a new part of your brain. Give it a try!)

Step Two: Draw, in chronological order (earliest to most recent) starting at the bottom of the egg and working up to the top, pictures of your money memories. You don’t have to be an artist, and it doesn’t have to be a scene of the whole memory. Referring to Atwood’s memory as an example, she may have drawn a wheelbarrow, or she may have drawn two big eyes staring at some coins to represent “interest.” There is no right or wrong way… you are just getting your money memory out of your head and onto the paper (into the egg).

Step Three: After you feel you have drawn all of your memories (you are a financial advisor, so there could be a lot of memories), start back at the bottom again, and begin to identify if the memory was positive or negative with a + or – sign next to each one.

Step Four: After you have assigned all of your memories with a negative or positive sign (some of them might have even had a negative and a positive sign), consider the following questions.

- What were the biggest three positive events?

- What were the biggest three negative events?

Step Five: Thinking about these events, and maybe even some of the others that did not make your “top three,” begin to craft a list of financial lessons (and maybe even life lessons) that have grown out of these memories.

Step Six: Now looking at your list of lessons and your egg, write out an overall statement or finish the statement, “The moral of the story is…”

As a final step in the Money Egg process, try actually discussing your story with someone close to you (spouse, friend, maybe another financial advisor in your office). This is important for a couple of reasons.

First, discussing your findings can lead to greater insights. You and your discussion partner can learn a lot through explaining your memories, as well as your final “moral of the story” message. The discussion partner may ask questions and provide other viewpoints (and hopefully find this engagement with you enlightening as well as an opportunity to connect at a deeper level!).

Second, now that your thoughts and memories are out in the open – challenge yourself to understand how these memories have a place in your everyday life. For instance, is one of your newly discovered “lessons” related to how you work with clients in your financial planning practice? This may be a good lesson, and you will want to keep doing it. But then again, it may also be a lesson that you are placing onto others… a lesson that, as an adult, you may see that it doesn’t necessarily apply to others or wouldn’t apply in all situations after all.

The final reason to talk through the Money Egg exercise with someone else circles back around to empathy. Essentially, it is “easy” enough to write down your thoughts, feelings, emotions, and lessons, but to then actually share with another person puts you into a relatively vulnerable position. The goal isn’t to make you feel uncomfortable, per se, but it is hard to sort through the emotions trapped in our memories, and money can be a huge trigger for these emotions. So as you reflect upon and likely experience a little difficulty in sharing with others, it should help you remember or recognize how difficult it may be for a client to want to share a similar revelation, memory, or experience with you, too.

Money Messages And Money Scripts

Money messages, also known as money scripts, are yet another way we learn about money.

Money scripts are the messages and lessons we learn about money while we’re growing up, that become ingrained in us as “scripts” that we may unconsciously follow as adults. There are four money scripts in total: Money avoidance, Money worship, Money status, and Money vigilance. Each “script” has a varied number of beliefs associated with it. The comprehensive study on all of the scripts can be found here.

We return to Atwood for an example…

“We kids in the 1940s did usually have some pocket money, and although we weren’t supposed to talk about it or have an undue love of it, we were expected to learn to manage it at an early age.” (p.3)

Atwood’s comments about not talking about money and not loving money are actually related to two key unconscious money scripts: money avoidance, and money vigilance.

Yet while Money Scripts are often something we carry with us subconsciously as adults – the whole point of this exercise is that although they’re ‘scripts’ we often follow without even thinking about it – they can be unearthed and actually considered with a little focus.

In fact, a Money Scripts assessment was developed in 2011 by Dr. Brad Klontz and Dr. Sonya Lutter and uncovers and gives a name to the unconscious, multi-generational beliefs we may hold about money. Since the assessment was first developed, it has been used in a wide variety of settings… including financial planning offices.

The Money Scripts assessment can be used as a basic diagnostic tool for uncovering disordered money behaviors, and/or give an indication as to which disorder money behavior a person may be more or less prone to falling into. However, for the average person, it can simply be a self-enlightening tool to start a conversation on the money beliefs one holds (which is how we will use it today).

You can evaluate your own Money Scripts by taking the money script inventory. (Go ahead, we’ll still be here when you get back.)

Likely, as a financial advisor, you are money vigilant, and possibly a mix of one or two other scripts. But the real insight is to consider where or how you may have learned these Money Script messages in the first place, and how they came to be so central in your life (such that you become a financial planner!).

In other words, much like the last exercise, the bigger goal or the internal work here is not just to identify your Money Script (or your Money Egg memories), but really about figuring out from whom these messages may have come from and investigating their circumstances around the message(s).

I will use myself as an example. In my own life, I often heard: “As a woman, you MUST be able to take care of yourself financially. Do not rely on a man.”

In many ways, this is a harmless thing to encourage some self-reliance. Some others might even agree it is a very good thing to teach a young woman.

Mind you, though, this lesson was taught to me by generations of women who had some very negative experiences with men and money. It wasn’t just a happy-go-lucky, “I’m a woman so hear me roar” message… it was, in fact, a rather scary warning, with deep emotional undertones that greatly influenced me, and still influence me today in my own marriage with my husband.

However, knowing where the message comes from, who it comes from, and why that message would come from them – I am now better able to decide how, why, and when this money message should be applied in my life. And whether it is still as relevant and necessary in my financial life today, as it may have been for the women who inculcated this Money Script in me when I was younger.

You will hopefully be able to, having just completed the Money Egg, be able to trace back and connect your Money Scripts with your money memories. As a bonus round, if you find that you are unclear about a message, a script, or a memory – do a little more digging. You can actually call up other members of the memory and ask them questions about what was going on at the time, or why they had explained something to you about money or life in the way that they did.

These revelations can be extremely powerful and eye-opening. As a kid, and even as an adolescent moving through life picking up bits of information along the way, you will likely find that you have a different take or a different outlook on that event now that you are an adult. Ensure that you can understand and connect as an adult to the things you, at least partially, thought you knew or understood as a kid, and get yourself as much context as you can around these beliefs, because it will help you to decipher how, why, and when you may or may not want employ the script.

Narrative Financial Therapy And Social Norms

Humans communicate through stories. It is how we remember information best, and how we connect with those around us. What is more, we tell ourselves stories about ourselves, and our behavior… and sometimes, these stories are not super helpful, nor are they multi-dimensional. In therapy terms, we would say humans are prone to writing “thin” stories about themselves.

As a quick example, how many times have you heard a person (maybe even a client) say, “I’m not good at math.” This thin description can spiral if the person is not fully aware of it and its “thinness,” and lead to further (potentially problematic) beliefs about oneself, such as turning into, “I’m terrible at math, so I’m going to be terrible at money, too.” Such subsequent beliefs can then lead to insecurity, depression, and anxiety because no one is really that one dimensional. We all have strengths and weaknesses and having a richer description like, “I’m not the best at money, but I’m great at finding financial professionals and doing research so I’ll be fine,” leads to more opportunities instead. But you can’t change the narrative if you’re not aware of the (sometimes subconscious) narrative in the first place.

Moreover, the two previous exercises have prompted you to get in touch with personal stories, but we can also connect with and discuss things that we have learned via “social norms,” which are ever-changing and in many ways just as powerful if we use them as a yardstick for measuring ourselves.

Turning to Atwood for another example …

“Debt can have another kind of entertainment value when it becomes a motif, not in a real-life plot line, but in a fictional one. How this kind of debt plot unfolds changes over time, as social conditions, class relations, financial climates, and literary fashions change; but debts themselves have been present in stories for a very long time” (p.86).

Now, we won’t be covering the literary history of debt in this next exercise, as Atwood has already done that for you in her book Payback. Instead, we are going to look at a couple of literary/media examples of money, to demonstrate the way in which money and plot lines have changed over the years, and then get into one last exercise as it relates to the power of narratives in our own everyday lives.

We are all very familiar with the story, A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, and his infamous character Mr. Ebenezer Scrooge. Mr. Scrooge was a horrible guy in the beginning (miserly and evil), but after being visited by Jacob Marley’s ghost, he transforms (becoming giving and kind). The story focuses on how giving money away makes everyone feel better. Flash forward in time to today, though, and we have examples like the Kardashians (or other wealthy) reality TV shows. These individuals are wealthy, spend lavishly on themselves, and are praised by our society for what could be said is often outlandish behavior.

Now consider how weird it is, and how strange social messages may become when we accept that we live in a world where both of these two totally different stories of wealth, and how to behave with wealth, co-exist. No wonder we have such confusion in our financial lives!

Narrative financial therapy, though, can help give us some insight and hopefully, given all that you now know about yourself and the money stories swirling around in you and outside of you, will help you to expand on your money story in a new way.

Narrative financial therapy has been adapted from - you probably guessed it - Narrative therapy. In Narrative therapy, the goal is to construct a more well-rounded story about oneself, as opposed to being stuck in a “thin” story – even if the world around us often shares “thin” stories. Ebenezer was a miserly jerk. The Kardashians are rich and crazy. Or “I’m successful because I have $XXX of AUM.”

To get started, pick out a money memory or a money fact that you have uncovered about yourself, that you might be feeling some apprehension about; for instance, maybe you do connect with the money script belief that your net-worth (or the size of your practice) is a reflection of your self-worth. This is a good “thin” story example, because taking an overly extreme focus on your practice can be detrimental to the rest of your life… after all, telling yourself that you are your AUM (or you are only as good as your practice is profitable) does not leave much room to talk about how you might also be a wonderful parent, a good role model to clients, a great friend, and an extremely ambitious individual. By working through some additional self-reflection questions - associated with narrative therapy - you can begin to see further how this single message can be understood and expanded in a more constructive manner.

The five question types in Narrative Financial Therapy are: deconstructing, externalization, sparkling event, amplifying the preferred narrative, and the audience. Each type of question takes the “thin” story, breaks it down, and adds to it. The list below provides some examples based on the money script, AUM (or size of revenue/practice) = self-worth.

You may choose to go through this exercise on your own, but like the past two…it can be good to talk through it with a trusted listener.

- Deconstructing: How has this belief impacted your relationships? What do you feel you learned from your parents or your society that tell you that this belief is true? When it is not true?

- Externalization: What name would you give this belief and the issues it causes in your life?

- Sparkling Events: In the past, was there a time in which you held a different belief about your self-worth? What was different about that time in your life?

- Amplifying the Preferred Narrative: How has your new understanding of your belief and its context impacted an important relationship in your life?

- Audience: As you continue to expand your relationship with money, how will other people know that you are growing or changing?

Remember that these exercises are meant to help you understand yourself, but also to get you in touch with how difficult sorting through a personal financial belief may be. We ask our clients to do it all the time… and because it is so commonplace to ask probing financial planning questions, we can forget how stressful, icky, and even scary it feels to be the one in the spotlight. Use this reflective time to consider and really get in touch with how your clients feel when going through the same process with you.

Conclusions

When we work in “helping” professions, it can be worthwhile to take the time to understand where or how our own “stuff” comes from. Which, as financial advisors, is all about exploring our own money memories, money scripts, and narratives … and maybe even our desire to help (with money) in the first place… and realizing how much may actually come from and be a reflection of our past experiences.

If you don’t have time to go through all the exercises now, that’s OK; it is not necessarily recommended that you do all of the exercises in quick succession anyway. Instead, try doing one a week for three weeks, and consider journaling about your experience. Because again, developing a greater awareness of the self is a great way to develop greater empathy for clients and their experiences.

In my own experience, going through these exercises doesn’t change the belief that I have been practicing for the past 30+ years of my life, but it does stop me from being a slave to those emotions that seem to well up out of nowhere when talking about money or discussing estate planning. You might not be able to stop believing that your AUM and the size of your advisory firm is a reflection of your self-worth overnight, but with time and practice you can learn to recognize when you are answering or thinking in auto-pilot, and how that may or may not be what is most important or helpful way to be thinking and considering the issue or situation at hand. (For instance, feeling like your advisory firm always has to keep growing because it increases your perceived self-worth, even though the firm doesn’t really need to keep growing to be financially successful and achieve your personal goals!)

Finally, once you have gone through these exercises for yourself – from the Money Egg to the Money Scripts and Narrative therapy discussion – you may even want to implement some of them into your own practice, as financial therapy and its many tools can have a number of good applications in an advisory firm. These are just a few more tools that, after you use them on yourself and get a little practice/training in using them, may make great additions to the work you are already doing with your clients.