Executive Summary

As financial advisors know, talking to clients about money can get emotionally charged, especially when the discussion concerns major (and potentially traumatic) life events. And sometimes, clients can become so distraught or unable to face the challenging issues in their past… even as the failure to deal with those issues prevents them from moving forward in their financial future. Which can also be distressing for a financial advisor who is striving to help, but who may recognize that the help the client needs is beyond the scope of what the advisor can provide and that referring the client to a mental health professional is the best course of action.

In practice, though, the point when a referral should be made is not always clear. As while it might be obvious that a client who has expressed (for instance) suicidal thoughts, or is otherwise in acute mental or emotional distress, is in need of a mental health professional’s services, how can a financial advisor tell when a client might just be “sad” (and who might simply need an empathetic ear to move forward with their financial planning recommendations)? And when a referral is in order, how does the financial advisor actually give that referral in the first place, without offending the client and potentially driving them away?

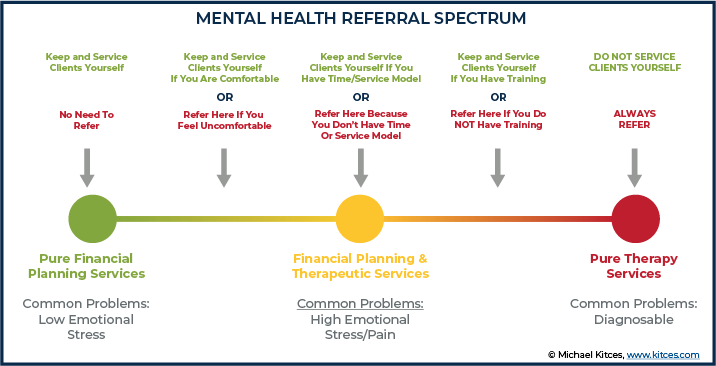

To understand when and how to involve an outside mental health professional, it is helpful to consider how money issues can impact an individual’s emotions across a spectrum of stress/anxiety. On the one hand, even common, everyday issues such as basic retirement planning or changes in income levels may be mildly stress-inducing, while more serious issues such as a death in the family or divorce can be very upsetting. On the other hand, at the farthest end of the spectrum are issues that involve disorders and conditions that are psychologically diagnosable, such as addiction, clinical depression, and hoarding behaviors.

To decide whether a referral to a mental health professional should be offered, the first factor to consider is the financial advisor’s own comfort level with the client conversation. Some firms have specialized models designed for clients working through emotionally-charged issues (e.g., divorcees, widows/widowers, etc.); these firms often already have processes in place that can more easily accommodate these clients’ needs, which, in turn, may make it easier for advisors to work with clients themselves, versus offering a mental health referral. On the other hand, if the financial advisor is uncomfortable with a client’s emotions that arise during a conversation, the best course of action can simply be to recognize and acknowledge the client’s distress, and to offer a referral for the client to see someone who is better-equipped to help the client with their stress or anxiety. And even if an advisor is comfortable working with a client who is experiencing high levels of stress, it may still be better for the advisor to refer the client to a mental health professional if they don’t actually have the time capacity (and thus ability) to fully service the client’s needs.

Of course, there’s still the challenge of just bringing up a mental health professional to a client in an unawkward way in the first place. One way to normalize the referral process is to discuss mental health referrals to clients as part of any other referral resource (e.g., CPAs, estate planners, etc.) early in the relationship, and reviewing those resources periodically during annual service meetings, which can then help clients be more comfortable accepting the referrals should the need ever arise. For advisors uncertain who to refer to, a helpful way to identify suitable mental health professionals is for them to personally make use of the mental health professional’s services themselves, which can give them the opportunity to discuss with clients, from firsthand experience, precisely what clients can expect when making referrals to see those professionals. However, some advisors may not have time to vet a network of referrals, or may have clients in need of immediate attention from a mental health professional. In these instances, advisors can work directly with the client to make calls together to find a suitable professional (or ask the client for permission to reach out to friends and family who can help with this).

Ultimately, the key point is that financial advisors should not be afraid to refer clients to mental health professionals, and that it’s perfectly OK to recognize that there is a level of emotionally-charged issues that clients experience, which advisors are not necessarily trained and equipped to handle (especially when those issues impact, but themselves are outside the purview of, financial planning itself). Advisors who are able to identify a network of mental health professionals that they can have on hand to use as referral sources, can, over time, develop a strategy to broach the subject of making referrals with clients in the first place, and make the process of providing mental health referrals a natural and comfortable process not only for themselves but for their clients as well.

I write a lot of articles about the emotional side of money. More to the point, I often suggest within those articles that financial planners give or be prepared to give referrals for clients to see a mental health professional.

And I suggest this – giving mental health referrals – because money is emotional, and financial planners are not always wanting, willing, or even able to help clients through these issues (that may impact a client’s ability to implement their financial plan, but aren’t actually within the domain of financial planning itself), and they are definitely going to see these issues in practice.

Research from Dubofsky and Sussman in 2009 found, after collecting interviews from 1,726 financial advisors, that 35% of the advisors reported helping clients through the death of someone close to them, 25% reported dealing with conflict between a child and a client, and over 20% reportedworking with clients with experiencing one of the following: marital problems, children’s emotional issues, conflicts with extended family members, and spending addictions. Just under 20% of advisors reported being asked to help with general mental health concerns depression, or general unhappiness. And around 10% of advisors had been asked to get involved with children’s addictions (drugs, gambling, spending) or the client’s own addictions.

Accordingly, practitioners need to decide how they want to navigate these issues, let alone intervene because they are inevitably going to come up. How will you respond when clients with marital stress fight with each other over or about money? What about when clients are going through a grieving process from the loss of a loved one and at the same time are struggling to handle money issues resulting from a large inheritance or insurance death benefit?

Moreover, money often influences and speaks to our deeper, personal thoughts and perceptions of who we are – what does the money in my bank account say about me as a professional, as a success (or failure), or as a provider? – and sometimes, these more personal and emotional aspects of money can cause a good deal of stress or anxiety, which might be better addressed by a mental health professional who has been trained to help patients work through such mental-health related (i.e., stress or anxiety) issues.

As while a client would not see a therapist for financial advice, they may also not get much benefit on a holistic level (not to mention the help they might actually need to work through serious psychological distress) from talking to a financial advisor about emotional issues. As such, financial advisors need to know how to give referrals to mental health professionals.

Yet, exactly how to give that referral, without making the conversation especially awkward (or potentially making the client feel like you have just told them they are “nuts”?), can be hard and extremely uncomfortable for both the financial advisor and the client. Thankfully, though, there are a few key considerations that advisors can easily implement to make giving mental health recommendations much easier and not so uncomfortable.

When Financial Advisors Should Rely On Mental Health Service Referrals

Financial advisors know, clients know, humans know… money issues and personal emotional issues often go hand in hand. Money is a means to acquire physical things or to pay for certain services that are often attached to emotional experiences; for example, someone may feel that if they only had enough money, they could buy a specific something, and if they are unable to get that something, they might end out feeling sad, upset, or angry. Or if someone is able to attain a certain level of savings in their bank account, they may consider the accomplishment as validation of their own sense of self-worth (or consider the failure to do so as a personal failure or character flaw).

Financial Planning Services And Mental Health Referrals Span Across A Spectrum of Emotional Stress Levels

For financial advisors who have troubled clients, it can be helpful to think of how money and life experiences affect an individual’s emotional state of mind on a spectrum, from low- and high-stress situations (which the financial advisor may be equipped to deal with) to psychologically diagnosable conditions (such as severe anxiety, clinical depression, and addiction; these are situations where the financial advisor should definitely refer the client to a mental health professional for help).

First on the spectrum are the least severe, everyday issues that clients struggle with. For financial advisors, these issues often connect their clients as people (e.g., their expressed emotions, psychological state of mind, and personal goals) to their money (e.g., their bank account or investment portfolios). Some of these issues might include aging, non-life-threatening health conditions, a change in income levels, or concerns about investments.

Often times, these topics are very comfortable topics for financial advisors to discuss from a planning perspective – they have clear, measurable, and often ‘plannable’ to-dos; for advisors, the discussion around them is relatively routine and probably not particularly emotional.

But in fact, a lot of these everyday issues are probably the emotional stressors that have pushed your clients into your office in the first place – the issue bothers them, perhaps causes a little stress, but the client want to attack this issue and move forward.

Example 1: Jane is a long-time client and has unfortunately just been laid off from her job, where she had worked for the last 25 years. Jane made her appointment to discuss next steps, but as she walks into the office she just starts crying.

The financial advisor knows why Jane is going to be coming in and that Jane might be upset. As such, they offered a therapeutic experience for Jane by having tissues out and preparing Jane’s preferred warm drink. They met Jane at the door and greeted her with a hug. By meeting her at the door, as opposed to being summoned from the office, the advisor shows that they expected her, and that they are ready to see her, without having to say anything.

Jane is visibly upset and cries for a little while, but after a few minutes gives you a weak smile and says that she is ready to discuss next steps.

The advisor had scheduled an additional 30 to the regularly scheduled meeting to allow for time to let Jane cry, talk through her feelings, and not have to rush through the meeting.

While Jane is sad, she is not overwhelmed and is eager to proceed with the meeting.

In this situation, the advisor felt that the therapeutic experience of simply offering kindness and empathy would be the most appropriate approach, and that a mental health referral would not be necessary.

Next on the spectrum are issues that can still be measured and addressed through planning solutions offered by the financial advisor, but that burden the client with a very heavy emotional weight. For instance, the loss of a loved one and the deep grief that the widow(er) may feel, loss of a job, or a life-threatening disease.

Financial planners help clients with estate planning issues so, at least in that capacity, advisors can help clients with planning around the loss of a loved one. As shown above, empathetic and thoughtful care for a client can go a long way in supporting the client and meeting them where they are at. However, some clients may be more impacted by the emotional stress of their situation even though the planning has been flawless and may need help from a mental health professional, beyond what the financial advisor can provide.

Example 2: Mary is a long-time client and has sadly just lost her husband, Mark, of 65 years. After rescheduling her meeting four times, Mary made her appointment to come in to discuss next steps.

When Mary walks into the office, the advisor gives her a warm hug and offers her some hot tea. But Mary is unable to stop crying and after a few minutes says that she just cannot do this today.

Mary is heart-broken and is not at all ready to move forward, but assures her advisor that she just needs time before she can discuss next steps. She is still grieving, and the financial advisor recognizes that it would not be appropriate to push her to move forward when she is not ready.

While the advisor once again feels that offering a therapeutic experience is the best approach for Mary, they also consider offering a mental health referral if Mary continues to struggle moving forward and makes a note to have one ready for their next meeting should the need arise.

While some emotional issues that financial planners see can involve clients with mild stress and anxiety that don’t need a referral, there may be other situations causing clients quite a bit of distress, such as marital or ambiguous loss issues, which may or may not need a referral (depending on the advisor’s comfort level and even their service model, which can sometimes be designed specifically to work with clients experiencing certain emotionally-charged issues). And while some problems may seem manageable with no need for a referral at first – for instance, a grieving spouse who initially appears to be in control of their emotions – they may escalate to a point where the client begins to exhibit reckless behavior and display signs of self-destruction, when a referral would be useful for the client.

Furthermore, even though some financial planners may be comfortable working with a client with serious psychological issues (e.g., some advisors may not feel compelled to fire a client struggling with hoarding), they should not put themselves in a position of counseling their client through such serious issues. While all of these issues can potentially be carried into the financial planning relationship, the advisor should feel free to acknowledge the mercurial nature of emotions at any stage and that it would be normal to feel uncomfortable (and perhaps even be unable) to continue working with the client who later expressed more severe signs of distress.

Last, on the opposite end of the spectrum from common, everyday issues, are the situations that cause extreme distress, such that the client may have a truly diagnosable psychological condition. Financial planners might recognize this in clients in a number of ways, such as with a gambling addiction, hoarding disorder, extreme anxiety, or the admission of suicidal thoughts and depression. In these cases, clients definitely need a referral.

Example 3: Carol is a long-time client and has sadly just lost her husband, Curtis, of 65 years. Like Mary, Carol is very upset and when she arrives at the office, the advisor offers support by giving her a hug and offering her tea.

But as Carol walks into the office, she begins to cry violently and cannot stop. She does not look like herself. As the advisor tries to calm her down, Carol admits, through her sobs, that she has not been eating, and outside of coming in for the meeting today, had not left her bed in a week and feels she would be better off dead, too.

Realizing that Carol is in a potentially dangerous state of mind, the advisor empathizes with Carol and thanks her for trusting them to share this personal information. They acknowledge that they understand Carol is having an extremely difficult time, and that Carol might benefit from speaking with one of the firm’s recommended therapists who can help her work through her feelings.

In this example, it is clear that Carol’s emotional state might pose a risk to herself – under these circumstances, while the financial planner can offer therapeutic gestures to comfort Carol while she is in the advisor’s office, it is most critical, for Carol’s own health and safety, that she be referred to a mental health professional.

Financial planners are not mental health practitioners (nor is it likely that they want to be) and thus it makes sense that, if a client has a clearly diagnosable issue, one should help the client find a licensed mental health service provider.

Counseling clients with diagnosable mental health issues should always be handed over to a mental health professional, 100% of the time.

Yet, how exactly does a financial planner decide where the divisive line exists for them personally, that separates when they should keep and service the client versus referring them to a mental health professional? They cannot do it all, especially when it comes to dealing with severe issues threatening the health or well-being of a client. And how should they respond when those less-serious middle-ground issues start becoming even more serious, moving out of the advisor’s comfort zone?

While a good rule of thumb for financial planners is to consider providing a mental health professional when conversations or meetings start to make them feel uncomfortable, these questions are best considered with some basic background information to understand why they are often so confusing (and maybe emotional…) for financial planners in the first place.

Financial Planners Are Not Trained (Or Licensed) To Practice Therapy

As just one example, the large majority of students in CFP-registered financial planning programs are not taught about mental health as part of their core financial planning curriculum. And really, most programs, if they touch on anything psychology-related, will only do so in the context of behavioral finance via an investments class or an estate planning class – and it is important to note that behavioral finance does not address the same issues as mental health therapy.

Rather, behavioral finance simply examines the effects that psychological, cultural, and social factors have on an investor’s financial and investment decisions. For example, from behavioral finance we know that automatic savings contributions or automatic bill paying is an effective way for clients to meet their savings and budgeting goals. This is not therapy. This may not even require much of a conversation with the client. There is very little, if anything, involved in talking about automated banking transactions that might address mental health; in many ways, the solutions offered through behavioral finance may even avoid getting into the mental health domains altogether in the first place.

For students of financial planning who do have core classes that touch on mental health and financial health issues, they still do not get licensed to provide therapy. For example, I teach at Kansas State University in the CFP program and we discuss how a client’s risk tolerance impacts their investments, and how family dynamics may dictate estate planning needs.

While the course material we cover might be a good start for my students to start thinking about the issues that will come up, it does not necessarily prepare them, as new financial advisors, to help a client sitting in front of them who has just shared something potentially life-threatening that makes their heart skip a beat. (An area that even therapists themselves struggle with, despite the fact that they have received literally years of hands-on training!)

However, even though financial planners with little or no formal training in mental health therapy may find it difficult to recognize the point when they are in over their heads, there are a few tools to help them identify when they are faced with an opportunity to offer a therapy referral.

Know Thyself (And The Difference Between Being Therapeutic And Doing Therapy)

A first step to knowing where financial planning ends and where therapy should begin starts with the financial advisor knowing where their own comfort levels are, and the differentiation between what is considered as being therapeutic, versus what can be considered as providing therapy.

Refer back to Mary in Example 2, the middle-ground example, in which Mary is heart-broken and not yet ready to move forward with the financial planning discussion.

In this situation, the financial advisor has different ways they can work with Mary; three potential reactions are as follows:

- Recognize The Client’s Discomfort and Give A Referral Right Away (Good To Do). Thank Mary for coming in and let her know it is okay to reschedule; you are happy to wait until she feels ready to continue. Ask if it would be okay if you follow up with her in a week to set a new appointment. In the meantime, remind Mary that your office works closely with a counselor who has helped another client (or even you) through an emotional time, and that you would be happy to help her make an appointment.

- Have an Empathetic Conversation and Give A Referral At The Close of The Meeting (Good To Do). Thank Mary for coming in. Sit with her and offer a warm cup of tea, sharing some fond memories of her late husband Mark over tea. When Mary pushes to talk about the estate plan, let her know you hear her and understand her request by repeating back to her, her own comment about wanting to review the estate plan. Assuming Mary responds affirmatively, the financial planner follows her cue and proceeds with the discussion. As Mary is getting ready to leave the meeting, remind her that your office works closely with a trusted counselor who has helped another client through an emotional time and that you would be happy to pass along the contact information if she wants it.

- Doing Therapy (Bad To Do). The financial planner remembers from a book by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross on grief that there are five stages and decides to help move Mary through them by telling her she has to start picking up the pieces. Ignoring Mary’s resistance, the financial planner starts to discuss the estate plan. No referral is given. The advisor is trying to move Mary forward and Mary is not ready. This is a simple, but important distinction; successfully helping the client and avoiding “doing therapy” really involves waiting on the client. Financial advisors are fixers; while this is a great and important role, financial advisors can only really ‘fix’ those who want fixing.

In the “Doing Therapy” reaction, the financial advisor attempts to provide therapy without the requisite training. And while the advisor’s intent may be truly to help the client, failure to acknowledge the client’s emotional needs can unfortunately cause more harm than good.

In the other two reactions (recognizing the discomfort, and having an empathetic conversation), the referral is given at different times. In both cases, the financial planner is not attempting to offer therapy, nor are they assuming that they know which course of action is best to address the client’s mental health needs. In both of these reactions, though, the financial planner is being “therapeutic”.

In other words, the financial planner is using communication techniques (spoken and via body language) to let the client know that they care for them, that they are supported, and that if they want to talk, the financial advisor is prepared to listen intently and respond with compassion. In fact, a lot of “being therapeutic” is simply listening intently and responding to the client in a way that let’s them know you have heard them, such as, repeating back to them, in your own words, what you have just heard them say.

Financial Planners Can Build (Therapeutic) Service Models, But They Should Always Give (Therapy) Referrals

To further clarify the line between being therapeutic while doing financial planning and actually providing therapy, it may be useful to highlight two aspects of the financial planning profession that financial advisors are already very comfortable with: service models and giving referrals.

There are some financial advisors who choose to specialize in more emotionally-charged areas of financial planning, such as helping divorcees, widow/widowers, and those with long-term care needs for themselves or for their family members. These financial advisory firms often have very specialized service models that allow them to charge for and take the client through both emotional as well as financial work.

An example of this may be a financial advisor who has gone through Sudden Money training or has perhaps gone through Financial Therapy training, or maybe they have been coached on Life Planning and they now use this specialized, often therapeutic training, to develop specialized service models. In all three of these practitioner-focused designations, financial advisors are taught communication skills. For instance, using open-ended questions as opposed to close-ended questions is a simple communication change (though it can be somewhat difficult to do well in practice!). Training in these areas can grow an advisor’s comfort level with a range of therapeutic topics and also with giving the referral. Training may also help you to know how far you might want to expand your financial planning services in order to encompass new services directly aimed at working with clients through tough emotional times.

Even though these financial advisors are not providing therapy and are not taking a client through the grief therapy process, their service models allow them to be therapeutic. For instance, financial planners with therapeutic training aim to communicate more openly (verbally and non-verbally) and will likely have longer meetings. They are okay with silence (harder than it sounds) and tend to be excellent listeners. If the financial planner’s firm does not offer special service models that require therapeutic communication, this does not mean that they cannot be a therapeutic financial advisor and be comfortable sitting with their clients – but if they are not comfortable or if the service model simply cannot do this profitably, that is okay, too. In these settings, mental health referrals might just come sooner and with greater frequency.

Moreover, all financial planning practices, specialized or not, give referrals. Financial planners are a trusted source of information for taxes, estate planning, and other services pertaining to financial planning… and they can also be a trusted source for mental health referrals.

Giving referrals is a service implicitly offered by all financial planners and is done in the client’s best interest to protect their financial (and overall general) well-being. Financial planners should not provide therapy they aren’t qualified to give; the same way a financial advisor knows not to attempt to practice law, they should also know not to attempt to practice therapy.

How Financial Advisors Can Refer Clients To Mental Health Professionals – And Not Stress Out About It

Before fully jumping into these next steps, we want to recognize that some of the suggestions in this article take time. Importantly, if you are reading this article and need help right now and don’t have the 20 or 40 hours to immediately find, meet, and connect with mental health professionals to refer your patients to – there is still a way for you to take action today.

If you are working with a client who is currently in severe distress, ask them if there is a trusted friend or family member that you can call in order to grow their circle of support. You can let them know that you care about them, that you are concerned about their well-being, and want them to have someone to talk with and not be as alone.

Assuming the client agrees to giving you contact information for a trusted friend or family member, call that friend or family member let them know about your concern, and that the client might benefit from seeking out mental health services.

If the client says they do not want you to call anyone, then ask if you can call them again in a few days to check-in. At that time, you can ask again if there is someone you can call on their behalf and/or suggest speaking with a mental health provider directly.

Your conversation may look something like this:

Mary (Client): Thanks again for calling, but I don’t want a bunch of people calling me nor do I want to be a burden to my friends and family members. So, no, there is no need to call anyone on my behalf.

Financial Advisor: I respect your decision Mary, but now, for me, mental health services come to mind. You cannot be a burden if you are paying a professional to listen. Have you considered speaking with a counselor? If you would be up for it, we can make a few phone calls together and see if we can find someone for you to speak with in the near future.

In this example, the financial advisor has avoided using dramatic or paternalistic language and has respected Mary’s autonomy. For instance, they have not said, “Mary, I am scared for you” or “Mary, you really need to see someone because I do not think you are well.”

The advisor has respected Mary’s decision-making but remained persistent in getting Mary to agree to help herself. The financial advisor also suggested making a phone call together. This, again, might take a little time, but it also ensures that the mental health appointment gets made. If Mary is feeling so overwhelmed that she is not eating or sleeping, the idea of calling a few mental health offices is also going to be overwhelming. Offering to call together releases some of the burden, but again still respects Mary’s autonomy.

Now, if you are not in immediate need of helping a client with severe emotional distress and are able to invest some extra hours into the process, the first important step in learning how to eloquently and confidently give a mental health referral is to understand how therapists work and what their specialties are.

The mental health profession is wide, from social workers to psychologists, and the mental health profession is varied, from services provided to help individuals with clinical depression, schizophrenia, anxiety, marriage counseling, and job rehabilitation. For instance, a psychologist may only work with couples or may specialize in grief. The following list is a quick ‘who’s who’ breakdown of therapists and how they work.

Psychologists. These individuals hold doctoral degrees in clinical psychology or other specialties such as counseling. They are qualified to carry out specific forms of behavioral therapy such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. They are licensed by state.

Psychiatrists. These individuals are medical doctors who, unlike psychologists, are able to prescribe medication and diagnose illness. They are qualified to treat complex and serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, severe depression, and bipolar disorder.

Counselors, Clinicians, and Therapists. These individuals have a master’s degree in mental health, counseling, psychology, therapy, or other related fields. These individuals have varied specialties which can often be identified based on their licensure, which is also held at the state level. For example, a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT) is different from a Licensed Clinical Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselor (LCADAC). Many counselors, clinicians, and therapists are also able to carry out specific forms of behavioral therapy.

Clinical Social Workers. These individuals also have a master’s degree, but in social work. They are also licensed at the state level and work with individuals to improve and/or manage mental health. Social workers differ from counselors mainly based on the types of clients they work with, and often focus on how the individual integrates into their community; therefore, they often work on different types of issues with clients.

Financial Therapists. These individuals have at least a master’s level education in both mental health and finance. As licensed mental health practitioners, they are licensed to practice in their respective states.

Now that we have identified the different types of mental health workers, the next step is to get to know some therapy organizations and go meet some therapists.

As noted above, mental health practitioners are licensed at the state level, and you can find mental health practitioners in your area at PsychologyToday – all you need to do is put in your zip code!

You might also consider attending a conference where you can meet and get to know (1) financial professionals who do therapeutic financial planning, (2) financial professionals who are interested in working with mental health practitioners, (2) mental health practitioners interested in working with financial professionals. Where is this wonderful place you might ask? Well, this year the Financial Therapy Association is holding its annual conference from October 9 – 11 (and will be co-locating with XYPN’s annual XYPN Live Conference in Denver, CO). While the conferences will not have ‘joint sessions’, the opportunity to mix and mingle is not one that should be missed if this is an area of interest. It is also great place to learn more about these topics and meet practitioners in this area.

Another large, mental health organization where you can meet mental health workers interested in finance is the Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education (AFCPE). If you want to talk to mental health professionals that don’t necessarily specialize in finance, try reaching out to the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) and see if you can find a conference or a gathering in your area.

Vetting Mental Health Workers For Referral To Clients

Now that you know about the different types of mental health workers and where you might find them, the last step is to get a little therapy yourself. As while the best referrals and recommendations that you probably have for CPAs or estate attorneys come from the ones you have actually worked with, therapy is no different.

This may sound really scary or strange, but we all have “stuff”; many financial planners become financial planners because of their own stuff, so it is not going to hurt you to do this work. You might even find that you learn a lot about yourself! Moreover, don’t just meet with one therapist, try meeting up with a wide variety of mental health professionals and see how it feels.

However, before just picking up the phone and making an appointment with the first mental health worker you find, do a little investigative work and take some time to interview a few therapists about background. Questions to consider:

- What do they know about money and counseling clients with money issues?

- What is their specialty?

- Who is their typical client?

- How can you pay for their services?

- Have they ever received training on working with clients on financial issues?

- How do they feel about their own financial life?

- Describe a typical client relationship.

Remember, you are going to therapy for yourself but in some ways you are also vetting them for work with your clients. So, other things you might consider once you go and meet with a therapist or two can include these additional questions:

- Did you like their office?

- How fast were you able to get an appointment?

- Did you like their responses to your questions?

- Did you enjoy your therapy session?

And even if you discover (or already know) that you do not want to offer new services, training would still prepare you for those tough phone calls and meetings. Basically, even without training, your clients are going to want to talk to you. You are who they feel comfortable with and who they trust.

How Financial Advisors Can “Normalize” Mental Health Referrals

Again, for financial advisors who need help with a client right now and do not have the time to engage in the extra steps suggested in this article, ask the client to agree to letting you call a friend or family member. If the client refuses the option to contact a friend or family member, suggest calling a mental health provider together.

However, for financial planners who can take the time the time to do the “get-to-know-a-therapist” homework (it is highly suggested that they do), then the next few suggestions will help you to implement a seamless and eventually stress-free therapy referral process.

First, make mental health services a part of your third-party lists, and consider the mental health service providers just as you would any other Center Of Influence (COI). Financial planners that have done the homework will have a list of two or three different providers, with different specialties, and likely different or varied pay systems. These mental health practitioners should be added to the places where financial advisors keep the names of other outside service providers they often recommend.

With new clients, as you bring them on board, share this list. Spend a part of at least one of your initial meetings explaining third-party relationships. Talk about the CPAs you work with, the estate planners, and the mental health practitioners, and explain their roles and how they can help clients. In addition to explaining the specialties of each professional, financial planners can share their own personal experience working with the mental health professional if it seems pertinent to the conversation or if clients have questions.

With existing clients, brief them on the changes or additions to your third-party service list as though it is a “housecleaning” item. For instance, introduce the new or updated list as part of an annual meeting. The goal here, again, is to bring up working with a mental health practitioner early and often.

Moreover, the most important thing to do in bringing these relationships up in the client-advisor relationship is to mention them early and often. In doing so, the financial advisor sets the tone that this is a normal, positive action. Waiting to bring up mental health services until the referral is actually needed may be too late to make the referral with complete ease. Yet, again, this does not mean that advisors should not refer.

Advisors can call friends or family members (if the client has agreed to it) and suggest a mental health referral. Alternatively, the advisor can ask the client if they can make a phone call or two together to find a mental health provider. In either of these scenarios, it is 100% acceptable and even encouraged that advisors present this as a normalized process (even if it is the first time the situation has come up).

For instance, the advisor can mention in their conversation with the client, or the friends/family of the client, that they know from working with other clients how difficult this time can be and that it can be helpful to speak to a professional. Normalize the fact that what they are going through is scary, hard, emotional, and that it is totally okay (and a positive thing!) to request additional help at this time.

Another great way to introduce ongoing clients (and even brand-new clients) to the idea of working with a mental health practitioner is to allow them to interact before services are ever even needed. Earlier, we discussed a number of ways in which a person’s emotions and money collide. Any of those topics, from the mundane to the more serious, would make for an appropriate “lunch-and-learn” or client event.

For instance, design a client event around ambiguous loss and planning for diminished or (in)capacity, where a trusted estate planner talks about the technical parts… and a trusted mental health professional talks about the emotional parts (and is thereby introduced to clients).

The mental health practitioner can also talk about more positive topics. This is often an over-looked consideration, that therapy can also be used for “good” things, too; it is by no means limited to addressing the “bad” stuff. Life changes, no matter how good, can be stress-inducing. Financial planners know that more money is generally a good thing but that it can be stress-inducing all the same. Yet, doing some “therapeutic” work like putting together a money mission statement can be really fun for clients. Another “good” topic a mental health professional can speak about might be how retirees can keep themselves be and remain healthier in and through retirement by understanding the different aspects of positive psychology.

The Words To Say To Make A Comfortable Referral To A Mental Health Professional

When it comes to actually giving the referral, the trick is for the financial advisor to give a concise referral. For instance, a financial planner does not want to say, “Well, your issue(s) of X are beyond my area of expertise and I don’t feel comfortable attempting to handle them. I recommend you see a therapist”. As much as this may be true, it may make the client feel as though you think they are crazy. It is also extremely off-putting, and may make the client regret sharing personal issues with their financial planner.

When clients open up to their planners, this is often the sign of a good planner! Because chances are that your clients are opening up because they trust you. Accordingly, advisors shouldn’t shut them down by failing to prepare and practice giving a good referral. Instead, make them feel heard and safe by giving a good referral.

Instead, a financial planner can give a better referral by being very concise about what they are suggesting and why they are suggesting it. For example, they can say something like:

“Thank you for trusting me enough to share this information. I hear you when you say X, and I think for A, B, and C you might benefit from speaking with one of our recommended therapists who can do D, E, and F”.

In this example, being concise about what the client has said, why the recommendation is being given, and what the referral is being made for, makes it clear that you understand the situation and that you don’t think the client is crazy (as it is not one of the reasons you specifically listed).

It also makes it clear that you understand the services, which is reassuring for the client. In this example, the financial advisor is expressing that they have personally vetted the therapist and by having vetted the therapist it will make the financial advisor feel less awkward. Moreover, the planner is not just telling the client they need therapy in general, but actually is recommending a precise course of action by offering a service provider’s name, a specialty, and phone number.

Also notice in this example that the financial advisor thanks the client. This is important, because it may have been really hard for the client to share this information. The fact that they have shared it with you means that they trust you, so it is perfectly appropriate (and professional) to thank the client for their trust and to let them know you hear them.

Another way to bring up a referral is to say something like:

“Thank you for sharing that information with me, I know that must have been very difficult and I appreciate that you trust me with it. In these situations, it is a common approach in our office to work alongside a mental health provider…the mental health provider can…”

In the above example, there is a lot of normalizing going on. Normalizing is helpful as it serves to sidestep awkward feelings. In this instance, too, the advisor is normalizing the process but not without treating the client as special and unique. This approach is valuable not only because it helps the client feel more at ease with the recommendation as a normal process, but also because the client and their issue are being treated with sensitivity and individuality.

Additionally, the advisor has vetted the therapist and is able to explain in detail the services that are available. Basically, not all people like the idea of lying down on a couch to talk about childhood trauma; accordingly, advisors can alleviate anxiety that clients may have about meeting with a mental health therapist by helping them understand what they can actually expect.

If you do not have time to vet a mental health professional, print out this article, and use it to talk about mental health services with clients. Demonstrate, with the research findings from Dubofsky and Sussman for example, that there are many things in the financial planning relationship that may also benefit from integrating a mental health relationship – and, importantly, that what the client is going through is completely normal.

Then take a moment to visit the PsychologyToday website together with the client, find a list of providers, and either offer to make calls with the client or send the list to a friend or family member and allow them to suggest meeting with a mental health provider.

When considering mental health referrals for clients, it is always helpful to remember that we all have “stuff”. Many financial planners likely become financial planners because of their own “stuff”, good, bad, and everything in between.

To have stuff is human; in therapeutic relationships, whether they be with trusted advisors or therapists, we can learn a lot about our own humanity.

By understanding the boundaries of their own comfort zones and building relationships with mental health practitioners, financial planners can give referrals with ease, and can develop a process so that those referrals are given when they will count the most.

Moreover, financial planners do not need to be the ones to take clients through this work, especially if “therapy” is really what is needed. In some situations, a client may need therapy when they are experiencing overwhelming grief and depression. In other situations, clients may just need to be heard, and a “therapeutic” financial planner is absolutely able to provide that support.

Financial planners can avoid getting caught up in situations where they might potentially cross the line from providing financial planning to providing therapy by being prepared with a referral to a mental health professional. Even financial planners with service models that have been designed to work with clients on more emotionally-charged issues should still give referrals as appropriate, because client emotions, and their mental health needs, ebb and flow. Clients might be okay during one meeting but not at all during the next.

As helping professionals, financial planners ultimately want to be there for their clients. When it comes to issues that require the attention of a mental health professional, though, they can best do this by being prepared to give a mental health referral.