Executive Summary

The benefit of contributing to pre-tax retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k) plans is the opportunity to receive an upfront tax deduction, and enjoy the growth that remains tax-deferred as long as the investments remain in the retirement account. For those accumulating towards retirement, this provides additional tax-deferred compounding growth that can help bridge the gap towards retirement itself. With the expectation that once someone reaches retirement, they will begin to take distributions – and Uncle Sam will finally get his share of the tax-deferred account.

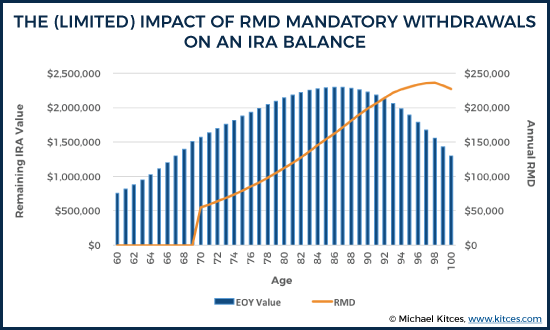

To ensure this final outcome, the Internal Revenue Code requires that retirement account owners begin liquidating their accounts upon reaching age 70 ½. Of course, for those who actually need to use their retirement account to fund their retirement lifestyle anyway, distributions will likely be occurring already. However, for those who don’t need the funds, the Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) obligation ensures that at least some money is distributed – and taxed – every year.

For those who don’t actually need to use their retirement accounts – yet, or at all – the mandatory withdrawals of the RMD obligation presents a substantial tax challenge, as the forced distributions not only trigger taxes on the RMD amount itself, but also risks driving the retiree up into a higher tax bracket when stacked on top of all of his/her other retirement income as well.

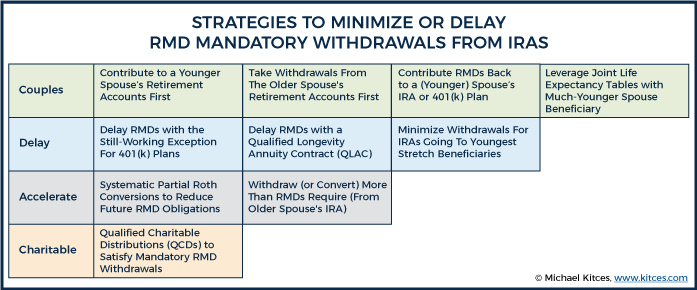

Fortunately, though, the reality is that there are numerous strategies that can be leveraged to manage and minimize required minimum distributions – both for those who have already reached the RMD phase, and also those still accumulating towards it, who want to plan ahead to minimize the bite of RMDs in the future.

Ultimately, it’s impossible to completely and indefinitely avoid the requirement to distribute retirement accounts – if only because, even to the extent the account isn’t liquidated during life, the beneficiaries will be subject to additional RMD obligations after the death of the original account owner. Nonetheless, the potential exists to at least partially manage and minimize RMDs, and mitigate some of their tax bite!

Managing And Minimizing Current Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) Obligations

For those who have already reached their Required Beginning Date – April 1st of the year after the year you turn age 70 ½, when the first RMD obligation is due – the options to reduce the tax consequences of RMDs are limited. Nonetheless, there are a few options available, either as a part of the Internal Revenue Code itself, or by managing around it.

Delaying The Onset Of RMD Mandatory Withdrawals With The Still-Working Exception

While the standard rule for required minimum distributions is that they must begin upon reaching age 70 ½, an exception applies under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(C)(i)(II) for someone who is still working and not yet retired in the first place, allowing any RMDs from that employer’s retirement plan to be delayed until the employee actually retires. Notably, this exception applies only to that particular employer’s retirement plan accounts, and not any other retirement accounts; other “old” 401(k) plans, or any IRAs, are still subject to RMDs upon reaching age 70 ½.

Example 1. Dennis is turning 70 ½ in 2018, but is still working full time for his current employer. He has a $300,000 balance in his 401(k) plan at work, a $105,000 401(k) plan from his prior employer (still held in the old 401(k) plan), and $55,000 in various contributory and rollover IRAs.

Because he is still working, he will not need to take any RMDs from his $300,000 401(k) plan until he actually retires, with the first RMD due for the year he actually retires. However, he will still be required to take his first RMD from his old $105,000 401(k) plan, and his $55,000 IRAs, for 2018 (which will be due by April 1st of 2019 as the first RMD).

To ensure that self-employed individuals don’t try to delay their own RMDs by continuing to work, the “still-working” exception does not apply to anyone who owns more than 5% of the employer stock (or profits interest in the case of a partnership or LLC). As a result, while “rank-and-file” employees can benefit from the still-working exception, business owners (who own more than 5% of the business) cannot, and must begin their RMDs upon reaching age 70 ½ under the “normal” rules for RMDs.

The good news of the still-working exception is that it avoids the requirement to begin taking mandatory RMD withdrawals from a current employer’s retirement plan. The planning opportunity, though, is to go one step further – and to roll other retirement account balances into the employer retirement plan, so those balances are not subject to RMDs yet, either.

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example, Dennis decides before the end of 2017 to roll his old 401(k) plan and his IRA into his employer’s existing 401(k) plan (presuming that the current 401(k) plan allows roll-ins). As a result, when 2018 begins – the year that Dennis will turn age 70 ½ - his only retirement account is the current employer’s 401(k) plan. Which means he will not be required to begin taking any RMDs in 2018!

Unfortunately, the 401(k) roll-in strategy is only possible if the employer retirement plan actually allows employees to roll in outside accounts (as not all of them do). In addition, under IRC Section 402(c)(2), only pre-tax dollar can be rolled into a 401(k) plan, and not after-tax dollars; as a result, any after-tax contributions that were previously made to an IRA must remain behind in the IRA (which ironically may be helpful anyway, to facilitate a nontaxable Roth conversion as a backdoor Roth contribution). And again, the roll-in strategy only works for those who are participants in an employer retirement plan and do not own more than 5% (which means major business owners aren’t eligible, nor are self-employed individuals with a solo 401(k) who by definition own 100% of their self-employed business).

Delaying RMDs With A Qualifying Longevity Annuity Contract (QLAC)

In recent years, the academic research has increasingly focused on the potential role of longevity annuities as a retirement income strategy. The longevity annuity is akin to a traditional single premium immediate annuity, which converts a lump sum into an (illiquid) guaranteed stream of payments for life (or a period certain). But while an immediate annuity begins payments immediately – as the name suggests – with a longevity annuity, the payments don’t begin until later. For instance, a 65-year-old couple might invest $100,000 into a single-premium immediate annuity, and get payments starting immediately of about $500/month ($6,000/year), while a longevity would might delay the first payment until age 85 (a 20-year waiting period), but make payments of more than $2,500/month (over $30,000/year).

The fact that longevity annuities provide very sizable payments in the later years is a combination of the simple time value of money (the dollars can grow for 20 years before they pay out), and the impact of mortality credits (payments are increased with the dollars of all those who don’t live the first 20 years until the payments begin). Which ironically makes the longevity annuity especially effective as a hedge against outliving one’s retirement dollars – as if the retiree lives a long time, he/she receives a whopping 30%+ payout rate (albeit starting in 20 years), and if the retiree doesn’t live a long time… then the retiree clearly didn’t outlive their retirement dollars, either.

The caveat of the longevity annuity, though, is that when purchased inside of a retirement account, it potentially runs afoul of the RMD rules – as if payments don’t begin until age 85, that’s 15 years later than the normal requirement for the onset of RMD mandatory withdrawals!

To resolve this issue, in 2014 the Treasury issued proposed Regulations that would permit a limited portion of retirement accounts to be invested into a “Qualifying” Longevity Annuity Contract (QLAC), without violating the RMD rules. Specifically, the rules stipulated that a retiree can invest up to 25% of his/her retirement account balances (up to a maximum of $125,000) into a longevity annuity, and the fact that the longevity annuity payments begin as late as age 85 will not cause that portion of the account to fail to satisfy the RMD rules. (Though the other 75% of retirement accounts must still take RMDs to satisfy the obligation for those other accounts.)

The good news of these rules is that by purchasing a QLAC inside of a retirement account, the retiree can effectively delay the onset of RMDs altogether, to as late as age 85, for at least 25% of the account. The bad news, however, is that a QLAC typically makes no payments until age 85, and a death in the interim may cause all principal to be lost (or alternatively, a return-of-premium guarantee may return the principal, but no growth for up to 20 years).

As a result, the QLAC is actually not a good strategy for RMD deferral alone, as given individual life expectancy of a 65-year-old is only around age 85 in the first place, the odds are that the retiree will forfeit all growth for 20 years (even with a return of premium guarantee) just to delay RMDs. In which case it would be better to just keep the money invested, and pay taxes on the RMDs, than to delay RMDs but lose all growth.

On the other hand, though, for those who want to purchase a longevity annuity, and are optimistic about their own life expectancy, it is arguably better to purchase a longevity annuity inside of an IRA (as opposed to buying it with other taxable-account dollars) to benefit from the RMD deferral on top!

Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) To Satisfy Mandatory RMD Withdrawals

IRC Section 408(d)(8) permits IRA owners to make a “Qualified Charitable Distribution” (QCD) from an IRA directly to a charity, and entirely avoid any tax consequences associated with the withdrawal. The donation to the charity is not eligible for a charitable deduction, but the distribution from the IRA is not reported in income in the first place; instead, it is a perfect pre-tax wash, for up to $100,000 of distributions per year from an individual’s IRAs (and only IRAs, as pre-tax employer retirement plans are not eligible).

The ability to make a QCD is limited to those who are at least age 70 ½ on the date the QCD is made, but the QCD itself counts towards the individual’s RMD obligation (which he/she must have, given that the age 70 ½ requirement to do the QCD in the first place means the IRA owner will have reached the RMD phase).

Example 2a. Harold just turned 71 years old and has an IRA with a $152,000 account balance. His RMD for the current year is $5,736. If Harold does a $5,000 QCD to his favorite charity, it will satisfy $5,000 of his RMD obligation (without any tax liability), leaving him with only another $736 to distribute (and report in income for tax purposes).

Example 2b. Continuing the prior example, if Harold instead did a $6,000 QCD from his IRA to a qualifying charity, his entire RMD will be satisfied (as his QCD is more than enough to cover the RMD obligation), and again there will be no tax consequences to the entire QCD (assuming it was otherwise eligible).

One important caveat of using a QCD to satisfy an RMD obligation, though, is that an RMD is presumed to be satisfied by the first distribution that comes out of the IRA for the year. And because IRC Section 408(d)(3)(E) does not permit an RMD to be rolled over back into an(other) IRA, once an RMD occurs, it is irrevocably distributed (and taxable).

Example 3. Chuck had a $7,400 RMD obligation for the current 2017 tax year. In February, he took a $7,400 to satisfy his entire RMD. In March, Chuck realizes that it may have been better for him to do a QCD instead, as he was planning to contribute to charity later in the year anyway. However, even if Chuck now does a QCD, it cannot be applied towards his RMD (which was already satisfied), nor can he undo his prior RMD (which is irrevocable once distributed). At best, Chuck can simply take the $7,400 distribution he took from his IRA, donate it to a charity, and claim a $7,400 charitable deduction as an itemized deduction on Schedule A, and hope that it at least mostly offsets his prior taxable distribution.

Consequently, one of the most straightforward ways to minimize the tax consequences of an RMD is simply to donate it to charity as a QCD (and to do so as the first distribution of the year from the IRA, to ensure that it actually counts towards the current year’s RMD).

Notably, though, this strategy is only effective for those who actually intend to donate to charity in the first place, where the QCD effectively kills two birds with one stone – satisfying the RMD mandatory withdrawal obligation, and the IRA owner’s charitable goals. For those who don’t actually want to donate to charity in the first place, it’s still more effective to take the RMD from the IRA, pay taxes, and simply keep the remainder.

It’s also important to recognize that for those who are making more substantial gifts, it is often even more tax-efficient to donate appreciated investments (e.g., stocks, mutual funds, or ETFs with embedded gains) instead, and use the charitable donation deduction to offset the income tax consequences of taking a (separate) RMD. The reason is that while a QCD is a perfect pre-tax deduction that avoids the tax consequences of an RMD, donating investments with embedded capital gains obtains a charitable deduction to offset the tax consequences of the RMD and also permanently avoids the capital gains taxes on the investment itself!

Leveraging Joint Life Expectancy Tables With A Much-Younger Spouse

Since a final update to the IRC Section 401(a)(9) Treasury Regulations was issued in 2002, all retirement account owners must use the so-called “Uniform Life Table” to calculate the annual RMD mandatory withdrawal amount.

The Uniform Life Table is the joint life expectancy of the retirement account owner, and a hypothetical beneficiary who is 10 years younger. It was adopted to simplify the prior rules that (re-)calculated the RMD for each individual retirement account based on the joint life expectancy with the beneficiary of that account. Which in practice had created substantial complexity and challenges, because retirement account owners had an incentive to name the youngest possible beneficiary to minimize lifetime RMDs… and then had to worry about accidentally disinheriting the actual intended beneficiary (e.g., a spouse) in the event of an untimely death.

Notably, though, while the Uniform Life Table is required to be used regardless of the actual age of the retirement account beneficiary (i.e., regardless of whether the beneficiary is actually more than 10 years younger than the retirement account owner), a special exception under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A-4(b) permits RMDs to be calculated based on the actual joint life expectancy of the retirement account owner and his/her spouse, in the event that the spouse is more than 10 years younger (which would produce a longer joint life expectancy, and therefore a smaller RMD when that applicable distribution period if divided into the prior year’s account balance).

The limitation to this special rule for much-younger spouses, though, is that the more favorable life expectancy table under Table II of Appendix B of Publication 590 is only available when the spouse is named as the sole beneficiary of the retirement account (and remain the sole beneficiary for the entire year).

As a result, in situations where the retirement account owner really is married to someone who is more than 10 years younger, the RMD obligation can be reduced by ensuring that spouse really is named as the beneficiary of the retirement account (presuming, of course, that there’s a desire to bequest the account after death to that spouse in the first place!).

In addition, because the more favorable life expectancy table for much-younger spouses applies only if the spouse is the sole beneficiary of the account, in situations where an IRA has multiple beneficiaries that include a much-younger spouse, it would be more favorable to split the IRA, and name the spouse as the sole beneficiary of his/her share. This ensures the more favorable RMD calculation for that spousal-beneficiary account, while the other retirement accounts continue to use the Uniform Life Table.

Contribute RMDs Back To A (Younger) Spouse’s IRA Or 401(k) Plan

While there are limited options to just not take a required minimum distribution – as it is required, by definition – one alternative for married couples is to simply re-contribute the RMD obligation back into a (younger) spouse’s IRA or employer retirement plan instead.

As while IRC Section 219(d)(1) does not permit anyone who has reached age 70 ½ to make contributions to an IRA, it may be possible for a younger spouse who has not yet reached age 70 ½ to make a contribution instead. Even using the dollars just received from a mandatory RMD withdrawal. Or alternatively, to contribute to an employer retirement plan like a 401(k) instead, where the contribution limits are even higher.

Of course, the biggest caveat to this strategy is simply that the younger spouse must be eligible to make a contribution in the first place – which means having earned income to contribute to the IRA (and not already be over age 70 ½ as well), and/or be earning enough salary to have dollars to contribute to a 401(k) plan (and be working for an employer who offers one).

Example 4. Richard is just turning 70 ½ years old and faces a $14,964 RMD from his $410,000 IRA as his first mandatory withdrawal. His wife Lucille is age 64 and still working part-time for an employer and making about $35,000/year. Currently, the couple lives off a combination of Richard’s Social Security benefits, and Lucille’s salary. As a result, they don’t actually need Richard’s RMD.

To manage the situation, Lucille increases her 401(k) contributions to $15,000, effectively “re-contributing” the RMD and providing a tax deduction that fully offsets the couple’s RMD obligation. Of course, the reality is that 401(k) contributions must be withheld directly from a paycheck; thus in practice, the Lucille will increase her contributions to $15,000, reducing her net salary to just $20,000/year, and then use the $14,964 RMD (and Richard’s ongoing Social Security benefits) to continue sustaining their lifestyle.

Withdrawing (Or Converting) More Than RMDs Require (From The Older Spouse’s IRA)

While the goal for most individuals looking to minimize their RMD obligations is to withdraw less from their retirement accounts – i.e., to not be forced to take the entire amount of the RMD – in some cases, the best strategy to minimize RMDs is actually to take more instead.

The reason is simply that annual RMDs are calculated based on the remaining value in the account – which means any further excess distribution taken from the retirement account reduces its value, and therefore the amount of the RMD, in future years.

Of course, when the whole issue is that RMD obligations are forcing money out of a retirement account that the individual didn’t want or need, it may seem strange to just further accelerate the process of taking additional distributions anyway. However, the reality is that when RMDs begin at age 70 ½, they only amount to approximately 3.6% of the account balance, which is far less than the 5%+ “safe withdrawal rate” that would otherwise apply to someone in their 70s, and may be grossly insufficient to cover retirement spending needs given that the distribution itself is pre-tax (which means the retiree can only spend the remainder). As a result, for many individuals, they will need to withdraw more than their RMDs just to maintain their lifestyle, anyway. Which raises the question of where to get the additional funds necessary to cover retirement expenses?

And the answer, if the funds must come from some pre-tax retirement account of the couple: take it from the RMD account, on top of the existing RMD obligations.

The reasoning is actually quite straightforward: if an RMD must come from some pre-tax retirement account, it’s better to take the additional distribution from the same account that is already funding the RMDs. Because the only alternative would be to take it from the other (ostensibly younger) spouse’s account. And if that spouse is younger, then his/her account can simply stay intact for a longer time horizon anyway, before any RMD must begin.

In other words, if the couple has reached the point where one (older) spouse is subject to RMDs and the other (younger) spouse is not, allow the younger spouse to keep as much of their retirement account dollars in place as possible, and take the retirement spending distributions from the account that was soon to be liquidated further by RMDs anyway! (And if both members of the couple are past the age for RMDs, it still pays to take any excess distributions from the older individual’s retirement accounts, who would have been subject to the largest RMDs in future years anyway.)

Example 5. Fred and Ethel are ages 79 and 72, respectively, and must each take RMDs from their respective IRAs. Fred’s IRA is worth $270,000, and his RMD at age 76 will be $13,846, while Ethel’s IRA is $175,000 and has an RMD obligation of $6,836. The combination of their RMDs of $20,682 are sufficient, when combined with the couple’s moderate Social Security benefits, to cover their household expenses.

However, an unexpected roof repair requires the couple to take another $10,000 distribution from one IRA or the other, and they must decide which account to draw from. They decide to take the distribution from Fred’s account, as the older of the couple, because it will have more of a benefit on reducing his RMD next year than Ethel’s, given the difference in their ages. After all, when Fred turns 80 next year, his RMD on that $10,000 would be $535, while Ethel’s at her future age 73 would be only $405, saving the couple $130 in RMDs.

Of course, saving “just” $130 in RMDs may not be substantial in any one year, but done systematically over time, the cumulative effect of always taking any “excess” distributions from the older spouse’s IRA can substantially reduce future RMD obligations.

In addition, the reality is that this strategy is not only relevant upon reaching the RMD phase. It is relevant any time a retired couple is considering which of their retirement accounts to take distributions from. As any time there is a choice – i.e., both are over age 59 ½ and not subject to early withdrawal penalties – it continues to be beneficial to draw from the older spouse’s accounts, that were closer to the RMD phase anyway.

Example 5b. Continuing the prior example, assuming instead that it is 10 years prior, where Fred is 69 and Ethel is 62, and the couple needs to fund approximately $40,000 of distributions from their IRAs to pay for retirement expenses before their Social Security payments have begun. Because they are both over age 59 ½, they can take a distribution from either Fred or Ethel’s IRAs without an early withdrawal penalty.

However, by taking the distribution from Fred’s IRA, his account balance is reduced by the full $40,000, which will reduce his first RMD (due next year as he reaches age 70 ½) by $1,460 – which is fortunate, as he doesn’t anticipate needing very much from his IRA once he begins his Social Security payments next year upon reaching age 70. By contrast, if the distribution was taken from Ethel’s account, the full RMD for Fred would still be due next year, on top of his Social Security income also scheduled to begin next year.

Systematic Partial Roth Conversions To Reduce Future RMD Obligations

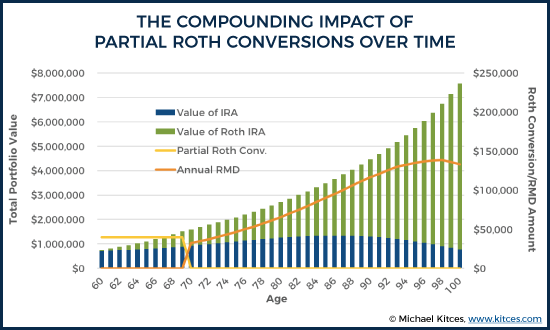

For those already facing an annual RMD obligation, taking additional distributions from the account of the oldest spouse can at least help to whittle down future RMD obligations. For those who haven’t yet reached the RMD phase, though, often the biggest opportunity is to engage in systematic partial Roth conversions, whittling down the size of the retirement account before RMDs ever begin!

The key planning opportunity is that, unlike traditional IRAs and other pre-tax retirement accounts, a Roth IRA is not subject to annual RMD obligations upon reaching age 70 ½ (and while a Roth 401(k) plan is, it can be rolled into a Roth IRA to avoid those RMDs). Which means that dollars held in Roth status can permanently avoid any RMD obligations for the rest of the retirement account owner’s life.

Of course, choosing to engage in a Roth conversion causes those retirement account dollars to become taxable immediately, which may not seem appealing when the whole problem with RMDs is that it causes those dollars to become taxable anyway. Or viewed another way, facing the potential for RMDs that force IRA distributions to be taxable in the future is bad, but just accelerating the distribution to be taxable now, instead, would just seem to be worse.

The distinction is that while those IRA dollars will be taxable either way – as a Roth conversion now, or as an RMD in the future – by converting to a Roth today, the funds can stay in tax-deferred (and ultimately as a Roth, tax-free) status for the rest of the account owner’s lifetime in the future. In other words, while both a Roth conversion and an RMD make the distribution taxable, with a Roth conversion the funds stay in a tax-free account, while with an RMD they are forced into a taxable investment account instead.

In addition, partial Roth conversions introduce the possibility to triggering income tax consequences on the IRA now, while tax rates may be lower, than in the future, when they may be higher (especially if the RMDs are projected to be sizable, and will be stacked on top of future Social Security distributions and other retirement income). Of course, current Roth conversions may also face high tax rates today – especially if stacked on top of current wages. But for many, a valley of low tax rates exists after retirement (when wages go away) and before RMDs begin, when systematic partial Roth conversions may be especially appealing.

Example 6. Betsy is a single 60-year-old female who recently retired with a $20,000/year Social Security survivorship payment and a $40,000/year survivorship pension from her deceased husband. Betsy also has a $200,000 brokerage account, and a substantial $700,000 IRA (the combined value of her original IRA, and a spousal rollover from her deceased husband’s 401(k)). In a decade when her RMDs begin, Betsy will face RMDs of upwards of $50,000/year (with an 8% growth rate in the IRA between now and then), propelling her into the 28% tax bracket even after her moderate deductions; by her 80s, the RMDs are projected to be more than $100,000/year, topping out the 28% rate and approaching the 33% bracket!

To manage the exposure, Betsy decides to do a partial Roth conversion of $40,000 each year for the next 10 years, which after her deductions just barely fills up her current 25% tax bracket, but stops short of the 28% tax rate. Repeated each year, this gives Betsy the opportunity to significantly whittle down her overall IRA exposure; in fact at this pace, her pre-tax IRA will still only be about $900,000 by the time her RMDs begin, which will produce RMDs of barely $35,000 (instead of $50,000), and allowing her to remain in the 25% tax bracket! In the meantime, Betsy will have accumulated a tax-free Roth IRA projected to have grown over $700,000 by age 70 ½!

Notably, the strategy of systematic partial Roth conversions is possible in the RMD phase as well, although an RMD mandatory withdrawal itself cannot be converted (only excess dollars on top of the RMD). While this strategy is often unappealing because the Roth conversion, stacked on top of the RMD, may drive the Roth conversion amount into higher tax brackets, often there is room to do at least a partial Roth conversion in the retiree’s current tax bracket (on top of the RMD) without rising into the next bracket… and reducing the risk that ongoing compounding growth in the IRA may lead to higher RMDs that increase future tax brackets anyway.

Minimizing Future RMDs By Contributing To A Younger Spouse’s Retirement Accounts First

As noted earlier, when it comes to RMD planning for couples approaching or already in the RMD phase, the optimal strategy is to spend from the older individual’s accounts first, and allow the younger – whose retirement accounts are further from the RMD phase – to compound as long as possible.

A natural extension of this strategy, for those who are still saving and accumulating, is to always maximize contributions to the younger spouse first, for the exact same reason. To the extent that the dollars accumulate in the younger spouse’s account, by definition those dollars will be further away from the onset of RMDs, and have longer to accumulate.

Example 7. Bradley is 53 and married to Angela who is 42. This year, they can afford to save $25,000 towards retirement. Given that Angela is further away from the RMD phase, the couple decides to maximize all the retirement account contributions in her name. Accordingly, they contribute $18,000 to Angela’s 401(k) plan, and only $7,000 to Bradley’s 401(k), because Angela has a 28-year time horizon to grow her IRA before the RMD phase begins, while Bradley’s time horizon is only 17 years until his RMDs.

Of course, as noted in a recent Journal of Financial Planning article by Caleb Vaughan, it’s important to bear in mind that disproportionately saving assets into one spouse’s retirement account versus evenly splitting amongst both may be beneficial for RMD purposes, but can also impact the division of assets in the event of a subsequent divorce. As a result, it’s important to consider and discuss the couple’s comfort level with disproportionate contributions to each individual’s accounts.

Deferring Lifetime RMDs And The Stretch IRA After Death

Ultimately, the benefit of minimizing and delaying RMDs is not merely that the retirement account stays intact and growing tax-deferred for even longer. It’s that any remaining balance in the retirement account is eligible to be further stretched after the death of the original owner by the beneficiaries… which means the period of additional tax deferred can be decades. Although notably, once the original account owner passes away, the retirement account must be distributed to beneficiaries – regardless of whether it is a traditional or Roth style account, as only spouses have the right to roll over the account and continue its deferral without immediate RMDs.

Alternatively, delaying RMDs can also culminate in donating the IRA or 401(k) plan to charity, especially since pre-tax retirement accounts are some of the most effective assets to bequeath to a charity (as the IRA, unlike other assets in the estate, does not receive a step-up in basis anyway).

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that while the RMD obligation can’t be avoided altogether, there are many ways to proactively plan for required minimum distributions, and to position retirement account strategies to delay or minimize the size of RMD mandatory withdrawals, and extend the period of retirement account tax deferral!

So what do you think? What strategies do you use to minimize or delay RMDs? What other considerations (e.g., division of assets in divorce) are important when using planning strategies to minimize or delay RMDs? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!