Executive Summary

As the popularity of financial planning has grown, so too have financial plans grown. Literally. In one recent study, 90% of advisors spend at least 6 hours to produce a financial plan, 40% spend upwards of 15 hours, and the sheer length of the physical financial planning document has grown dramatically over the decades.

On the one hand, a longer financial plan implicitly suggests that the plan must include more extensive analysis, more recommendations, and therefore be a “better” plan. And to some extent, that may be true. However, the caveat is that physical financial plans may have grown so large that the associated list of recommendations is too daunting to actually implement. In other words, the thoroughness of being fully comprehensive may not be a dazzling display of value, but simply overwhelming.

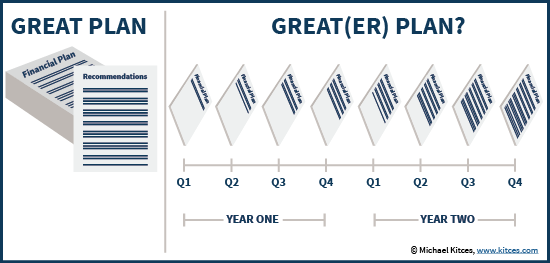

As a result, perhaps the best way to demonstrate the value of financial planning is not to make the plan as comprehensive as possible up front, but instead to make it comprehensive by building one module at a time over a span a weeks, months, or years – whatever it takes to help the client to actually implement, one step at a time, until everything is done. Which means in the end, perhaps when it comes to modular financial planning, the parts are actually worth more than delivering the whole up front, at least when measured by the success of actually getting clients to implement?

The (Literal) Growth Of The (Physical) Financial Plan

As an intangible service, it’s sometimes difficult to demonstrate the value of financial planning, especially during the initial stages of the process. In fact, when much of the value over time is about helping clients not cause financial harm to themselves (which helps them avoid the pain of making the mistake but also eliminates the perceived value of fixing it), and/or produces outcomes that are only evident in the very long run (e.g., we only know retirement was successful after several decades!), it’s difficult to demonstrate much tangible value to financial planning at all. Except when it comes to the financial plan itself.

In practice, the physical financial plan document is the one “tangible” outcome to an otherwise entirely intangible process and value proposition. It carries the burden of validating the benefit of planning, demonstrating that the advisor really did the analysis and work on behalf of the client, and supports the perceived credibility and value of the planner (even if few clients ever actually read it).

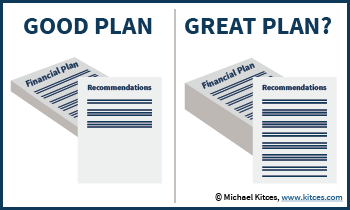

Unfortunately, though, as the financial plan document has become the physical manifestation of the “value” of planning, its size has grown – literally – in an attempt to demonstrate greater and greater value. The implicit concept – if a “good” plan is a big one with a lot of analysis and recommendations, then a “great” plan must be an even bigger one with even more analysis and even more recommendations!

Unfortunately, though, as the financial plan document has become the physical manifestation of the “value” of planning, its size has grown – literally – in an attempt to demonstrate greater and greater value. The implicit concept – if a “good” plan is a big one with a lot of analysis and recommendations, then a “great” plan must be an even bigger one with even more analysis and even more recommendations!

Notably, while many (most?) financial planners collectively acknowledge that clients rarely read such a full “comprehensive” financial planning document, it remains an industry standard to produce, given its ongoing role in building trust and credibility for the advisor and manifesting “value” in the financial planning process.

The Problem With The Comprehensive Financial Plan Document

The burdens of producing a long financial planning document are not trivial. An estimate from FPA’s 2011 Financial Plan Development & Fees study suggested that the average time to produce a financial plan varies wildly, but 90% of advisors spend at least 6 hours on a plan, and approximately 40% invest upwards of 15 hours of time to produce the financial plan. This is a significant “cost” in time for the advisor, which in turn results in a significant hard dollar cost to the consumer (with the median comprehensive plan fee at the time estimated to be $2,250, undoubtedly driven heavily by the professional time it takes to create it!). And of course, the longer and “more comprehensive” the plan, the higher the numbers will tend to skew as well, in terms of both time and cost.

Yet the challenge of such a “comprehensive” financial plan that grows larger and larger as the planner tries to demonstrate more value is that it’s not merely a greater investment of time and cost … it’s something that can become overwhelming and daunting for the client as well. And unfortunately, making clients feel overwhelmed can actually inhibit their ability to follow through on the recommendations and change their behavior! In other words, the more recommendations we present the clients at once, the less likely they are to implement any of them!

Just think of it in the context of your own life. What’s realistically easier to take on – a “To Do” list that has 3-5 items (to which more may be added as the initial ones are checked off throughout the year), or a “To Do” list that has 35 items representing everything you hope to accomplish for the year. The short list feels achievable; the long one, just daunting. In fact, the feeling of having too much to tackle all at once is such a pervasive problem, we even had a common aphorism to address it: How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

Modular Financial Planning To Stretch Out Comprehensive Financial Planning Over Time

So how can we help clients eat the comprehensive financial plan one bite at a time? By helping clients to break the plan down into smaller pieces that can be tackled one at a time, rather than trying to give them the whole elephant at once. In other words, if a “great” financial plan is the thickest one that gives the most thorough list of recommendations all at once, then an even greater financial plan (and an even greater financial planning process) is the one that helps clients get through the most financial planning recommendations one module at a time (recognizing that such things take time to do!).

Of course, for many planners the thought of not covering all modules together and giving all the recommendations at once is frightening. What if “something happens” and the client hadn’t completed a crucial recommendation yet? Won’t they be “harmed” by failing to tell them to do everything up front? Can we even give recommendations if we haven’t “done everything” in the first place?

The caveat here is that if giving them everything to do up front results in nothing actually being done, then trying to dump every possible recommendation on clients at once isn’t actually helping them at all. Comprehensive financial planning may feel like a bigger demonstration of value, but it may actually be less valuable than modular planning over time, in terms of getting clients to actually take the necessary steps to improve their financial lives. That’s the whole point. Comprehensive plans can actually risk overwhelming clients and lead to greater risk that key parts of the plan will remain un-implemented for a long period of time!

Notably, this doesn’t literally mean that recommendations should be hidden or kept secret from clients, per se, but recognize that if there is going to be a long list of recommendations given, that helping clients to prioritize them and break the plan down into manageable pieces is crucial (along with setting milestone targets for when each goal will be completed, so clients can be held accountable to their own commitments). Or better yet, consider determining with clients what’s most important to them during the data gathering and discovery phase of the process, and just prioritize doing those modules of financial planning first. If an insurance review is the highest priority, start there and then proceed on to the next segment. If it’s fixing the portfolio first, then begin there instead. Faster clients will get through the modules faster, and slower clients will do it more slowly, but each can proceed at their own pace – with ongoing nudges from the financial planner – until the whole plan is completed, over time. The key word being “completed”!

In other words, effective financial planning is all about setting priorities about the different modules of financial planning (insurance, estate, education, retirement, cash flow, etc.) so clients can actually get through the implementation phase, recognizing that the changes in behavior that are necessary to do so can be difficult for most clients but that planners have a responsibility to do what is necessary to help make it happen. Sadly, in practice the problem seems to be masked by the fact that few of us actually measure within our firms the average time it takes for clients to implement recommendations, and/or the percentage of recommendations actually implemented at all (a tracking and measurement challenge we’re still struggling to figure out how best to implement ourselves!). Nonetheless, there is clearly some opportunity to help more clients implement more recommendations more quickly (after all, if it was easy for them to do on their own, they likely wouldn’t be seeking out an advisor in the first place!), and delivering it to them one module at a time may be a good way to give them reasonable bites they can chew.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: the process of financial planning isn’t just about the process to assemble a comprehensive financial plan, but a process to get clients through a comprehensive list of recommendations. And recognizing the challenging realities of behavior change, our “industry standard” of analyzing everything up front, and giving clients everything to do all at once, may actually be doing more harm than good. So the next time you’re considering the steps to take to improve your planning process with clients, consider whether the “best” plan may not be the thickest plan with the most recommendations, but the plan that does the best job guiding clients through an ongoing process, one financial planning module at a time, on the client’s own schedule, for however long it takes for them to really get everything completed!

So what do you think? Should the quality of a plan be measured simply by its depth and thoroughness, or by the way that it is implemented over time? Is it really best to do financial planning "comprehensively" all at once, even if it risks being overwhelming to clients? Or is it acceptable (or even better) to do planning one module at a time, even if it "takes longer" if that's what is necessary to really help clients implement the recommendations?

The quality of the plan is, or should be, measured by the ability of the clients to implement, not the quantity of pages, or recommendations, within the plan itself. We are looking for quality, not quantity. To the point of comprehensiveness: You can still have a comprehensive plan in place but present on the pressing issues (i.e. the insurance or the cash flow section) for the client in a modular fashion. This gives the client, as you mention, less tasks for which they have to accomplish. I think it is acceptable to do planning in a modular fashion. Perhaps it depends on the client?

Excellent article. Definitely holds true for the Australian market as well.

Very good observations. This confirm why more and more, plans are delivered electronically and each section can be displayed with up to the minutes data and facts.

Points well taken. I’ve always done comprehensive plans. I don’t believe I can be true to my standards and not do so. There is so much to consider that to do less simply ignores pertinent information. What I’ve done is create, as a last page to my written report, an Action Plan. It is a bulletized list of actions that the client should take based on the detailed analysis in the report. What I think I shall adjust is the timing of the actions. I will prioritize them and give them time targets – e.g. next month, 1st quarter, etc. In this way perhaps they can order their actions better. What seems to me to be rather simple may to many be overwhelming.

Well done. Like any well planned five course meal, the process should facilitate great conversation, time to digest, and great satisfaction at the end.

Great article Michael, and we couldn’t agree more. Our planning process happens over several meetings (5-8 or more depending on complexity) but clients love that when they are done everything is in order.

One thing that we have found to be extremely helpful is at the beginning of every new planning concept we help the client get very clear on their goals. Then we help them visualize the impact that achieving all of those goals will have on them. Immediately after the goals discussion we layout the current situation, visually, and allow the client to determine on their own where they are on track and where they have issues. Obviously, if we didn’t do a good job designing the visual pieces we may have to guide the client in some areas that they may not immediately recognize as shortfalls or gaps.

By fostering a self-discovery process, it helps to engage clients throughout the planning process. Now, when we layout design recommendations that are tied back to the goals and objections….it’s as if they are writing their own plan. We then create an implementation schedule of all recommendations, along with the intended impact, and the clients accept or reject each recommendation. Because the recommendations are driven by the clients goals, most items are accepted and implemented.

The implantation schedule has realistic dates attached to every item and gets reviewed during all meetings going forward. As items are removed from the schedule new items can be added so it acts as a living part of the planning process and holds each party accountable.

I hope someone finds it helpful…it has been a huge positive addition to our planning process.

Michael,

Since I mostly practice remote planning, I rarely have in-person meetings making it difficult to view plans and discuss progress with clients. My solution was to create a Summary of Issues and Recommendations Form on Google Docs that I share with the client. I list all of the client’s issues and my recommendations with hyperlinks to each of the resources I recommend. For instance, if I recommend a particular Vanguard fund I hyperlink the fund so the client does not have to do anymore than just click. The form becomes a living document where we work through each issue until the client is satisfied. Some clients attack the form and implement each recommendation and some barely touch it. However, this process helps those wanting to implement their plans, and it shows which clients are serious because nothing could be easier than clicking on the steps that I provide. So, in a way it is a slow motion comprehensive plan, or what you described as a serial modular plan. Great job, as always.

Great POV as always. I think another benefit to this approach is the ability to incorporate other staff and advisors into the process. It does help to touch on the areas of need so that clients get a preview of the coming process, but asking clients to go through a detailed set of recommendations on a host of topics is a tough ask. Doing it all up front leaves the primary advisor as the sole messenger and results in a flurry of activity followed by a lull with the client getting to know only the advisor and not the firm.

Michael,

The Alliance of Comprehensive Planners model has always been comprehensive, but done in a modular fashion over, generally 3 to 4 months. We meet with clients every 2-3 weeks with a different topic each meeting. The time inbetween meetings is when the implementation takes place. Total time spent on the full plan is closer to the 15 hours listed in the FPA survey, but, by the time we are finished, the client has a comprehensive and usually fully implemented plan. No need to generate a hundred page plan or more at the start of the engagement. This method works, and because you work together with the client, we have very high client retention rates.

As a member of the Alliance of Comprehensive Planners I am another advocate of the modular approach. Clients often seek advice because they are overwhelmed with financial decisions and complexity. The ACP process teaches us to focus on meetings by topic – tax planning, portfolio analysis, insurance. This helps the client implement improvements because their take away To Do List is concentrated on a set of related actions. It helps clients implement and feel progress.

As Ike said about preparing for battle, “…plans are useless but planning is indispensible.” True financial planning is not a discrete deliverable that is obsolete the moment it is produced but an ongoing process of engagement which is open ended and responds to life changes as they occur.

Big difference between Financial Plans and Financial Planning. The former is static and becomes stale very quickly. The latter lives and breathes and guides the clients today and tomorrow. As a member of the Alliance of Comprehensive Planners (http://www.acplanners.org/) we use a modular process to advise clients A to Z with their personal finances. It’s truly comprehensive, holistic planning. Clients appreciate and value the service we provide.

Nice Michael. I teach a modular approach in the MBA Personal Finance course at USF. Makes it easier to assign homework to students that way, but seems like a more reasonable way to help clients actually implement as well. The planner can maintain the 80 page document and the comprehensive plan in the background, but the client can focus on a short list of actionable tasks that the planner can more easily monitor. As William said, “a slow motion comprehensive plan.” Joke – How do you eat a financial plan? One module at a time.

Ever since I read Michael’s article on Mind Mapping, we’ve moved away from “plans” to interactive mind-mapping for clients. The map gives them visual blueprint, and we can set dates for completion of certain tasks, attach web links to their accounts. The client can add a task too, and we receive a notification when they do. It’s the centerpiece of each client meeting, and any family member can look at the map and know exactly what’s going. The mind map is a living, breathing document.

Thanks for sharing Michael. I’m glad to hear the prior Mind Mapping article was so helpful! 🙂

– Michael

Michael,

I heard about this article from several members of

the Alliance of Comprehensive Planners (ACP), many of us who subscribe

to your newsletter, and enjoy a special discount. Since you spoke at

our conference recently in Philadelphia, many members on our Discussion

Forum have expressed some dismay that your article did not reference our

organization which is now 20 years old, and has trained over 1,000

advisors on using the ACP system.

The ACP system, since I started

developing it over 40 years ago, is the exact modular system you

describe in your article, with several additional advantages

(integrating tax planning and preparation, now introducing an

inter-generational retainer to include elderly parents and grown

children, a Roth IRA Legacy Trust strategy for wealthy clients, etc.).

We don’t use market timing, but a more sensible approach for real people

which is called “Functional Asset Allocation” which includes real

estate as a separate asset class.

Our

system enables a beginning advisor start our with younger, less wealthy

clients, and still save them more than the annual fee (we even utilize a

cost/benefit analysis in our New Client Presentation to show the

client how a comprehensive financial plan saves the client more than our

after-tax fee. Our advisors generally are more credentialed (CFP

required plus most are CPA’s, attorneys, or EA’s). Our members

practices, like mine, often evolve into large multi-advisor firms. We

have a staff of 12, client offices in 4 states, and over 200 clients

with almost $500MM under management.

May I suggest you let me

demonstrate this highly successful format. I would appreciate your

analysis to compare your suggestions with what already exists. As you

know, I respect and admire your intelligence and your dedication to

developing fee only planning as it should be, beyond mere asset

management. While we know you have formed your own organization for

advisors, I know you well enough not to assume your omission of ACP in

your article was not to exclude competitors.

Thank

you for your efforts in increasing awareness of the importance of

comprehensive financial planning. Bert Whitehead, M.B.A., J.D.,

Founder of the Alliance of Comprehensive Planners (ACP) — see

http://www.ACPlanners.org

Bert,

Thanks for the comment.

I don’t really view the concept of modular planning as being unique to any particular organization – arguably, it’s the roots from which comprehensive financial planning was built anyway – though clearly there are a number of organizations and advisory that have put particular forms of it into implementation. Certainly ACP is one that has done so, though there are a number of others as well. The purpose of this article wasn’t to recommend (nor therefore to exclude) any particular organizations that have tools for implementing modular planning.

Regarding looking at the ACP tools/process itself, I’m certainly up for looking at a demonstration sometime, as frankly I’ve never actually seen them in detail and don’t really know that much about the exact workings of the ACP system.

With warm regards,

– Michael

Modular vs Comprehensive Personal Financial Planning

The premise of modular financial planning is the thick by the pound comprehensive

plan is not only daunting but doesn’t lead to execution. And to add to this, I

might add, an inch is a cinch a yard is hard.

However, the argument for modular planning which sequentially adds up to a comprehensive

plan in increments bifurcates planning and goes against the fundamental premise

of personal financial planning – of coordinating the moving parts such that one

doesn’t solve one problem in isolation and creates two others (or more).

In fact, in the past, modular planning was just spin and a re-characterization of

a package sale by those in ‘financial services.’

There is a third way – which also has the benefit of increased continuity

–institutional memory of the planner and client as planners and clients move

on, pass on – as the thick unintelligible plans become ignored leaving no easy trail

to follow other than the shredder.

In applying to personal financial planning, a Managing by Objectives (something

99% of planners and 100% of those teaching planners mistakenly do not include

in their curricula) rather than setting the plan in just beautiful prose,

creates a repetitive form – which follows a process – objective by objective. Thus, once the client goes through one objective – he or she becomes more and more familiar of ‘the thinking’ behind

each objective – can easily find the answers he is looking for following the same process for the next prioritized (or

not) objective etc.

The beauty of this approach is it not only provides an easy to follow trail of

thought by each personal financial planning objective, it also cuts down on the

voluminous plans which are often are just validation by size (i.e. like the old

Gaines Dog Food Commercial –‘My Dog Is Bigger Than Your Dog’). (If need be to

justify fee or AUM by volume – attach an appendix per each objective).

An excerpted example – copyrighted – is attached which I employed versions of as

far back as 1977 when I was a in practice as a fee only personal financial

planning employing the ENOUGH(sm) process incorporating a managing by

objectives approach. Of course, one can change the measures used –i.e. %

probability under monte carlo etc etc in the income replacement upon disability

example attached or any other objective. For those sticklers arguing over which

measure etc – play the music not the note or you wind up as Warren Beatty said

in Shampoo, ‘I cut so much hair, I lost my concept.’

In the form example provided – each objective is no more than 5 pages and again

the process is repetitive in presentation – which allows both planner and

client to more easily track the objective.. Another benefit, by managing by

personal financial objective orientation (managing goals)– this changes the

model away from managing assets (external comparison to indexes etc) and back

to the client’s goals. Again personal financial planning – is about managing

& achieving goals – not a Trojan horse for

managing assets under management.

Thus, with this approach, comprehensive (the ((not if)) fundamental coordinated tenet

of personal financial planning) is not sacrificed in the name of modular (err renamed

package sale which is not planning). Furthermore, this form can be updated and

used objective by objective for the quarterly and annual meetings – becoming

more and more familiar and utilizable by the client in tracking. In addition,

this form – or a similar form – allows the client to manage the planner while

increasing the probability of institutional memory such that if the planner

leaves practice the successor planner is not having to start from scratch.

Form sent to Michael by email

Jim,

There’s nothing specific about “modular” planning that would it preclude it from being done objective-by-objective, exactly as you state here.

Granted, many people happen to think of segmenting modules by subject matter/CFP topic area, but there’s nothing specific about the concept of modular planning that requires modules to be done that way…

– Michael

Process, scope, topic, objective, relationship – what do we really do? With nearly 30 years of experience, I find my thinking is still evolving.

I am in my second year teaching the so-called “capstone course” that’s required before one can take the CFP exam. Comparing the academic textbooks to actual industry practice has provoked further thoughts. So, here is some preliminary thinking.

1) The emphasis on “process” – originally to establish credibility (“we’re not brokers”) – is overdone. First, the process is hardly unique to personal financial planning. Second, it’s how we produce “advice”. It’s the recipe, not the soup.

2) The comprehensive vs modular dichotomy, while standard in the industry, misses the essence of financial planning, namely the development and provision of advice on how to meet important goals after integrating into a system (specific to each client) the critical topical, factual, and motivational issues. A comprehensive plan, if too large, runs the risk of being taken as a list of concatenated one-off recommendations – especially if taken straight off the computer. Modular might be better integrated – and better advice.

These points can be further developed. Seems overall, the real issue is:

We are trying to brand our advice as superior (why and how); is it; could too much modular make it less distinguishable from transaction-oriented sales pitches?