Executive Summary

Monte Carlo simulations are an important part of an advisor’s toolbox when constructing a client’s financial plan, as they demonstrate the wide range of potential outcomes that a retiree might experience. These simulations inform the retiree of how much they can spend in the short-term to avoid plan failure in the future, and they also suggest corrective spending levels along the way as plans get updated – an immensely difficult task given that no one knows precisely what will happen. Advisors can assess a number of important variables through Monte Carlo simulations, the most important of which is the frequency of accomplishing the client’s financial goals.

However, when constructing plans that are guided by probability-of-success outcomes, advisors walk a delicate line. Creating a plan with a 100% chance of success, for example, may assume that the retiree has no flexibility in spending and thus will not recommend spending increases… which would present a risk that the retiree may die with too much of their money remaining in the bank, having missed out on experiences, memories, and comforts they could have had. On the opposite side, creating a plan with a higher chance of failure can make clients uncomfortable, given the uncertainty of the future. Accordingly, advisors strive to find the right balance between these two scenarios, and while practices vary in the industry, many advisors tend to target a fixed threshold— say 90% – to determine whether a plan is strong enough to actually implement.

One key assumption of the 90% threshold is that clients should accept a 10% probability that they may need to course-correct at some point in the future to achieve their goals, should investment returns prove unfavorable. While a 90% success threshold might be a suitable threshold for many clients, advisors should recognize that every client has a different willingness and ability to take corrective action when needed, and perhaps a one-size-fits-all approach should be reconsidered. Some clients may prefer a plan that requires course correction 50% of the time, while others may shy away from any chance of failure at all.

Fortunately, advisors can adopt simple processes to identify appropriate (and uniquely customized!) target success thresholds for their clients. Conversations with clients about risk management can evolve, such that advisors shift away from a focus on the unpredictable movements of the market and, instead, move toward more controllable variables within a financial plan (e.g., discretionary spending categories), assessing the corrective actions that a client would be willing to take if needed. By identifying a client’s willingness and ability to modify spending, advisors can utilize a more appropriate and customized Monte Carlo success rate that reflects the client’s true tolerance for risk.

Ultimately, a client’s retirement plan will be more effective when it largely comes down to their comfort with risk, rather than the advisor’s comfort with risk. Because if the scenarios have been discussed and both parties are comfortable with the plan – along with the adjustments that may be needed to stick to that plan – then clients will feel more confident and willing to take the necessary steps to deal with the market fluctuates in the short-term. And, of course, markets can also exceed expectations… not all adjustments need to be negative!

Using Monte Carlo Analysis To Assess The Viability Of A Volatile Retirement Portfolio

Advisors guide clients in identifying a reasonable balance between spending today and maintaining enough savings to support future financial goals. Which can be difficult in practice because of the unknowns of the future – particularly when it comes to market returns, that may average out in the long run but can still occur with an unfavorable sequence that results in a catastrophic drawdown before the “good” returns finally arrive (also known as “sequence of returns risk”). Not to mention the risk that future returns may average out to a level that is lower than returns of the past.

One of the most common ways to evaluate this uncertainty is Monte Carlo analysis, which rather than relying on straight-line assumptions of average returns (or a fixed projection of below-average returns), instead projects a wide range of possible future market returns – based on the probability that they will occur – and then evaluates how often those scenarios turn out to be successful (or not).

Not surprisingly, the retiring client may desire the idea of a plan that survives every possible scenario in a Monte Carlo stress test (i.e., a 100% success rate). However, advisors often need to help these clients understand that relying on a 100% success rate may be an overly conservative approach – after all, a Monte Carlo simulation typically assumes a retiree has no flexibility in spending, or portfolio asset allocation, nor any ability to adjust their financial goals in the event that the early years’ market returns are less than hoped for.

Most retiring clients do have at least some flexibility, though, and so a plan that may ‘fail’ a Monte Carlo stress test may actually be one that could have achieved all financial goals if just some small course-corrective actions were taken early on in the plan. At the same time, planning for a 100% Monte Carlo success rate means portfolio withdrawal rates must be low enough to survive even the worst series of investment returns… such that in most scenario outcomes, returns are significantly more favorable (if only because they’re not completely disastrous as the worst-case scenario projected!) and portfolio growth compounds dramatically over time, which can result in very large portfolio values at the end of a retiree’s plan.

As in the end, picking a conservative probability of success as a standard benchmark effectively means retirees must trim their spending upfront in order to achieve that high threshold of success… even though there’s a high likelihood they never needed to spend so little (and will simply accumulate ‘excess’ wealth they could have enjoyed along the way), and if they were willing to spend less, they could have simply waited and cut when it was necessary rather than upfront when it may not have ever been required!

Advisors who understand the shortcomings of a 100% success threshold educate their clients on why they can take a more balanced approach and safely plan with probabilities of success below 100%. Although industry practices vary from advisor to advisor, utilized success rates tend to fall between 85% and 95%, with advisors often applying a fixed success rate (say 90%) to each of their clients. This predefined threshold of success then acts as a guide for framing planning conversations, helping clients understand when their current plan ‘needs work’, and when their plan succeeds at an acceptable frequency.

This current practice of using a specific Monte Carlo probability-of-success target to assess the appropriateness of a retirement plan is certainly reasonable… on average. But like the proverbial six-foot man who drowned crossing a river that averages five feet deep, it’s important to understand when a process that works ‘on average’ is suitable and when it is not.

Incorporating Risk Tolerance Into Monte Carlo: Portfolio Volatility Or Spending Volatility?

Although advisors tend to utilize a standardized threshold of success in Monte Carlo simulations (again, say 90%), many do make adjustments to the expected return and volatility of each retiree’s modeled portfolio in the retirement plan based on an evaluation of the client’s risk tolerance. The caveat, though, is that this approach inherently equates a retiree’s tolerance for risk to their tolerance for portfolio volatility. Yet while clients may communicate their desire to avoid market volatility and losses, what they’re truly communicating is a desire to avoid the consequences of those losses.

These consequences – failure to accomplish financial goals and undesirable cutbacks to spending – are the risks that advisors should be working to align with client tolerances. However, the challenge is that when risk tolerance is viewed through a portfolio-volatility lens, it can lead advisors to implement portfolio-centric responses that don’t actually help address these underlying risks to the retiree’s spending. Recognizing this shortcoming is a significant opportunity for advisors to advance their risk management techniques and value proposition to their retiring clients.

Shifting Asset Allocation Does Not Necessarily Reduce A Retiree’s Risk Of Failure

The standard process of assessing risk tolerance often requires clients to respond to various questions describing acceptable portfolio drawdowns, or asks them to think about how they have reacted historically to periods of market volatility when considering the trade-offs they would be comfortable taking in the future. The objective of these assessments (and related client conversations) is typically to identify an acceptable asset allocation for the client’s financial plan that will serve to fit their unique risk tolerance.

Yet, in practice, the use of risk-tolerance surveys as a tool to set a client’s asset allocation often confuses the effects of market volatility with the risk of actually achieving their underlying retirement goals (or not). In other words, portfolio volatility and financial goal risk are not the same things. Instead, for many retirees, these variables are inversely connected, as taking on ‘too little’ portfolio risk (i.e., market volatility) can actually increase the risk of a long-term financial shortfall, while exposure to market volatility (and the potential for at least short- to intermediate-term portfolio drawdown) are unavoidable features of long-term wealth creation.

In fact, while there are certainly merits to ensuring that client portfolios do not exceed tolerable volatility thresholds (thereby preventing or at least reducing the likelihood of poor behaviors during market selloffs), shifts in asset allocation beyond a certain initial level of market exposure actually do very little to reduce the risk of falling short of financial goals.

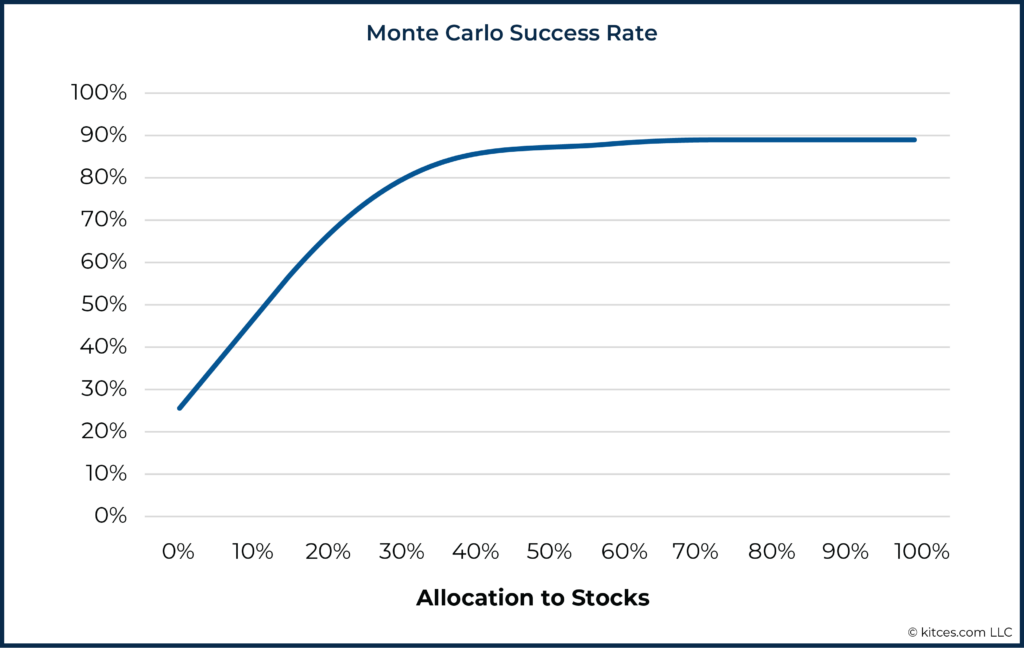

The chart below presents the Monte Carlo success rates for a simple financial plan using a variety of stock/bond allocations. The results are clear; the probability that a client will have to take corrective action to meet their financial goals is not reduced by adjusting their asset allocation beyond a certain level. In fact, there is a nearly identical shortfall risk when using any asset allocation mix between a ‘conservative’ 40/60 stock/bond mix and an ‘aggressive’ portfolio that is 100% invested in equities!

This phenomenon may seem counterintuitive when taking only market volatility into consideration. However, it makes sense when we also consider the impact of stock/bond allocation on return potential; because any reduction in portfolio volatility will be offset by a corresponding reduction in return potential, thus neutralizing the effect on success rates. Accordingly, while volatility may be reduced with more conservative portfolios, risk (of actually achieving the goal) is not. And conversely, increasing a portfolio’s volatility does not necessarily diminish the probability of success, because of the additional returns that can be generated by taking on greater volatility along the way!

Adapting Monte Carlo Success Thresholds Based On (Tolerance For) Spending Flexibility

Given the reality that tying a retiree’s asset allocation to their risk tolerance may not actually reduce the riskiness of achieving their financial goals, and that improving outcomes in potentially risky spend-down scenarios is primarily a function of the retiree’s willingness to make mid-course spending adjustments, arguably the entire framing of risk assessments themselves needs to be re-evaluated to focus less on risk in terms of portfolio volatility, and instead be oriented more towards the risk of spending volatility instead.

In practice, this determination is made by deciding what probability of success will be acceptable in a Monte Carlo analysis in the first place. While many advisors adopt different target thresholds, a 90% probability of success is often a popular choice. The inherent implication of such a threshold is that clients should be willing to take corrective action in 10% of scenarios that would otherwise end out in ‘failure’. Or viewed another way, it suggests that clients should be willing to accept a 10% probability of needing to make a downward adjustment in their future spending.

Yet while this might be a reasonable assumption for the average client, just as different clients have a different willingness to accept portfolio volatility, so too will every client have (potentially very) different levels of willingness and ability to take corrective actions and endure spending volatility. Which means these are also important variables to consider when determining the appropriate retirement planning recommendations.

Retirees Have Unique Levels Of Willingness To Make Adjustments To Their Financial Plans

When the foundation for risk shifts from portfolio volatility to spending volatility, a retiree’s risk tolerance is effectively defined by their willingness to course-correct. In other words, how willing is the retiree to make course corrections if they are falling short of financial goals, and what is their capacity to modify some component of their behavior, portfolio, or financial goals in order to redefine what success looks like?

As with risk tolerance in a portfolio volatility context, this will vary tremendously from one retiree to the next. Some retirees carry with them the assumption that they are hiring an advisor to avoid this very scenario; they are paying their advisor to do the homework upfront and want their advisor’s blessing to move forward through a plan of action that will avoid the need for course-correcting (or at least, negative course-correcting) along the way, where the only adjustments they would ever face are scenarios where they can ratchet their spending higher because they’re ahead of their original goals.

Other retirees might be more accepting of uncertainty in life, have a more adaptable/flexible attitude when it comes to their spending behaviors, and are very willing to make adjustments in the face of unfavorable outcomes. They’re the type of retirees who are comfortable simply rolling with whatever life (or in this case, the markets) throws at them.

Notably, in many cases, the risk tolerance for portfolio volatility and for spending volatility will be similar. After all, we often talk to clients about the ‘sleep-at-night’ factor, asking them what keeps them up at night. And while clients may communicate their fears of portfolio losses, often what they’re actually communicating is their fears of the consequences of portfolio losses – that if returns are poor, they might have to cut their spending, and those risk-averse clients don’t want to cut their spending. Which means those who are not tolerant of market volatility aren’t often tolerant of spending volatility either, while those who are tolerant of market volatility and portfolio declines will often be tolerant of spending volatility and the risk of spending cuts (that would have occurred with those tolerated market declines anyway).

Nonetheless, it’s important to recognize that the desire to course-correct is not uniform across all clients, and a one-size-fits-all approach will not work. Not only because of the variability in tolerance for spending volatility, but also simply because not all retirees have the same capacity to be able to change their spending if/when the time comes!

Retirees Also Have Varying Levels Of Ability To Adjust Their Retirement Plans

In addition to a retiree’s willingness to make adjustments to their financial plan, the ability or capacity to course-correct is another important component that will impact a suitable success threshold for the retiree’s financial plan.

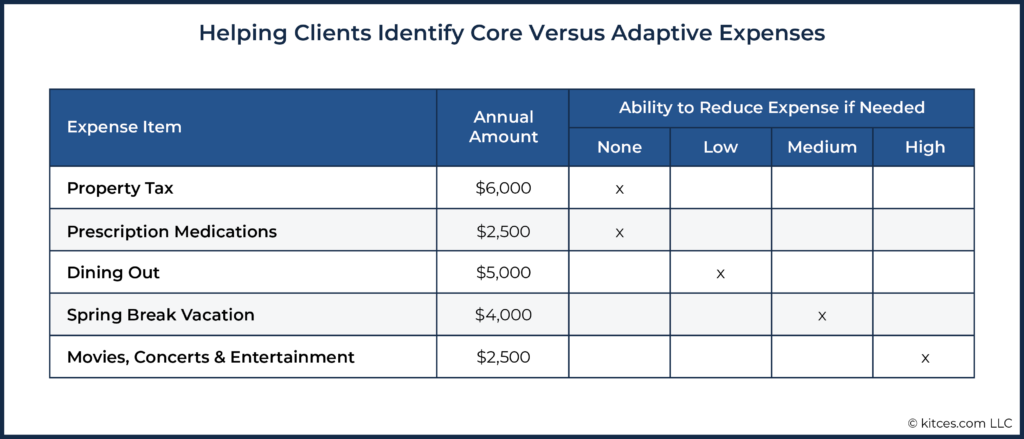

Every retiree has a different mix of income sources and spending components. A review of a retiree’s budget will include many core expenses such as property taxes or prescription medications (that can’t be readily adjusted in difficult times), as well as adaptive items like going out to eat or taking vacations (that could be eliminated or at least reined in if necessary).

Additionally, while each retiree will have a different mix of these core and adaptive expenditures, every retiree will have a different perception of whether adaptive items are really ‘adaptive’. In other words, a vacation to Florida in the winter might be perceived as a ‘want’ by one client, yet as the only opportunity to visit the grandchildren every year could be an important ‘need’ for another. Charitable giving is another area that one person may view as a critical line item, where another might be more willing to trim back if needed.

It stands to reason that the unique mix of core and adaptive expenses is an incredibly important variable to understand when determining an acceptable Monte Carlo success rate threshold. This point is most clearly articulated by thinking about the extreme case of a retiree who has only core expenses and no adaptive expenses. If this retiree has no ability to modify spending, should we be planning with the assumption that this retiree will find it acceptable to take course-corrective action in 10% of scenarios? Perhaps not, because those corrections would still be a ‘catastrophe’ for the inflexible retiree. Even as for another, with far more flexible spending, mid-course spending cuts to remain on track would simply be “no big deal”.

Thus, both a retiree’s willingness and ability to course-correct should be considered when determining an acceptable threshold of success in Monte Carlo simulation. Retirees with greater levels of willingness and ability should plan with different success thresholds than those with little or no willingness and/or ability to take corrective actions. Although a 90% success threshold may be suitable on average, it should not be applied universally to all clients. This is particularly notable in a world where advisors are continually looking for additional ways to provide value for their retiree clients and to differentiate themselves against the more automated competition, such as robo-advisors or Do-It-Yourself (DIY) software; customizing Monte Carlo success (or at least, “adjustment”) thresholds can be a valuable tool for advisors to demonstrate their ability to provide personalized services involving risk management and spending guidance. Advancing client conversations about risk away from the uncontrollable nature of market volatility and towards the controllable (spending) variables in a financial plan allows advisors to demonstrate the value of integrated wealth management.

In addition, being able to show retiree clients who do possess high levels of willingness and ability to take corrective actions that they can spend well above the amounts otherwise recommended by standard approaches that don’t necessarily apply to them is an extremely valuable service that creates a lasting bond between client and advisor.

In other words, highly flexible retirees might be quite willing to adopt plans that have as little as a 50% probability of “success” because, in practice, it’s merely a 50% likelihood of making spending adjustments that they are ready and willing to make. Yet a much higher probability of adjustment also substantiates a much-higher initial spending level in the first place, substantively raising their standard of living… that “still” has a 50% likelihood of not needing to cut at all!

Though in these instances, the planning process can often be better experienced by the retired client as an ongoing, personalized living process, where spending is constantly monitored to identify when it needs to be changed… rather than approaching the retirement plan as a one-time projection presented during a single upfront meeting whose sole goal is to cut spending to the point that the retiree will never need to adapt in the future (even if they readily could have!).

Customizing Monte Carlo Thresholds For Retirees’ Willingness And Ability To Adapt

Advisors can implement a more dynamic and flexible framework of financial planning into their practice by assessing a retiring client’s willingness and ability to take corrective spending actions in the face of market volatility, and then using those responses to target a uniquely acceptable success (i.e., adjustment) rate in their Monte Carlo simulations.

Assessment Of Retiree Willingness To Make Course Corrections

To assess willingness, advisors can either supplement or modify their current risk tolerance assessment methodology. In addition to preexisting behavioral questions about reactions to potential market declines, which are important to understand tolerance for portfolio volatility, advisors should also seek to understand how clients view the assumption of needing to make course-corrective spending changes in response as well.

Below are a few examples of questions that can be used to assess a client’s willingness to make adjustments to their financial plan.

- Market returns are fairly consistent over long periods of time, but are highly uncertain over short periods. If market performance over the next three years is well below long-term expectations, requiring you to take corrective action by reducing some adaptive expenses, how would you perceive this outcome?

A) Unfortunate, but part of the nature of planning in an uncertain world.

B) Disappointing; something I’d like to avoid if at all possible.

C) Unacceptable and a result of poor planning.

- If market returns are poor over the next three years, circle the approach(es) you would consider as a response:

A) Modify my financial goals to create a more feasible plan.

B) Lower some of my adaptive spending items to get back on track.

C) Accept a higher level of market volatility to improve expected returns.

D) I would not be comfortable with any of the options above.

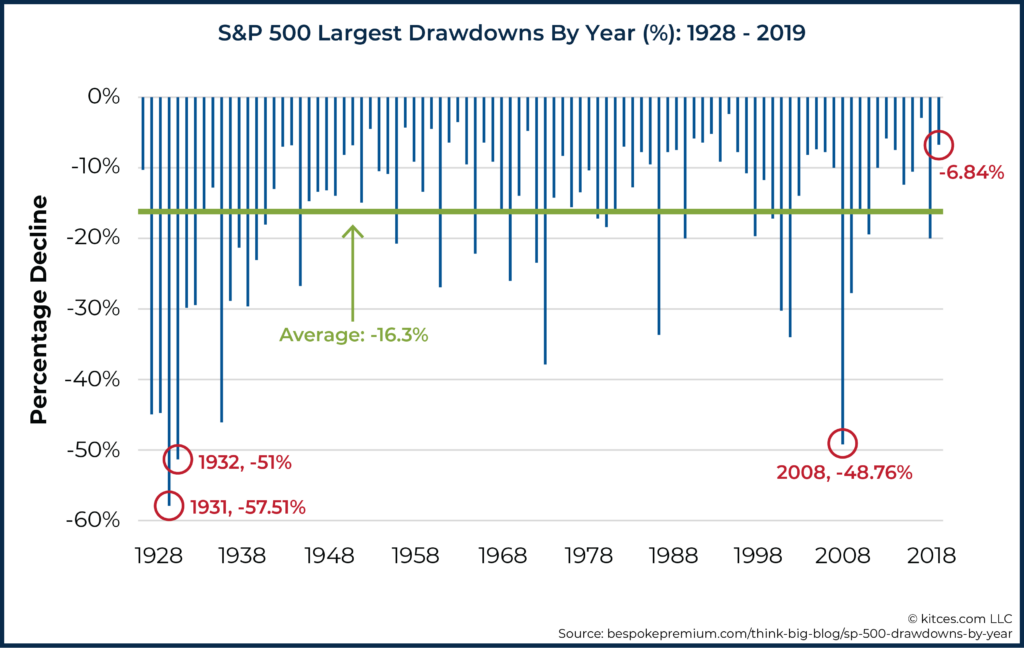

- The table below outlines the largest drawdowns for the S&P 500 in each calendar year from 1928 to 2019. Please complete the following statement: I should only expect to modify my spending if the market falls __% or more.

By asking such questions, advisors can gain a better understanding of which clients are willing and comfortable with making spending changes to adapt to future market returns, and which are not (and therefore would need a higher Monte Carlo probability reducing the likelihood that such changes would be necessary). Notably, the goal here is not necessarily to evaluate how much of a change they can afford to make – which comes next – but simply their willingness to make such changes in the first place. (As in practice, even when retirees can afford to trim their spending, some are simply more or less willing to do so than others!)

Importantly, by having these conversations upfront, advisors mentally equip clients for the possibility that these outcomes could occur and allow clients to make decisions today with these possibilities in mind. Which is much more preferable to waiting until poor investment returns require difficult (and perhaps unexpected) conversations to take place!

Assessment Of Retiree Capacity To Make Mid-Course Corrections

In addition to assessing a client’s willingness to make course corrections to their retirement plans, advisors can also benefit from assessing a client’s capacity to modify spending. To do this, advisors can walk through the client’s budget and talk about classifying items as either core or adaptive, and seek feedback on which items would be the easiest to reduce.

A simple expansion of a typical budgeting template, such as the format shown below, can be used to help guide clients through such an exercise. Advisors can ask clients about amounts that could be reduced in their adaptive expense areas, which also allows advisors to determine the total adaptive expense amount and percentage. This is important information for determining the targeted Monte Carlo success threshold, as discussed in the next section.

As retirees go through the process, some will have a very high percentage of line items that have little or no ability to reduce spending, while others may have a spending plan that is comprised primarily of line items that have a medium or high capacity to reduce spending. (Not necessarily to eliminate the line item, but at least to reduce it.) In turn, advisors can then even calculate a “spending flexibility” score (i.e., the percentage of their portfolio spending that is adaptive), based on the total percentage of the client’s budget that could be trimmed.

For instance, if “high” ability represents a potential 50% spending trim, “medium” is a 25% spending trim, and “low” is a 10% spending trim, then the sample budget above would have a total of $20,000 in expenditures, and $2,750 in potential spending cuts, for a total budget flexibility of $2,750 / $20,000 = 13.75%. More “conservative” retirees would have even less spending flexibility, while very “aggressive” retirees might have 20% to 30%+ spending flexibility.

With this information in hand, advisors can assess the potential spending reduction that could take place in a client’s plan should the need arise and compare that to annual portfolio withdrawals. The higher the flexibility as a percentage of portfolio withdrawals, the greater the client’s ability to take course-corrective actions in the future, and the lower their initial Monte Carlo probability of success can be (because by definition, the retiree can make the necessary adjustments if the adverse market return sequence occurs!).

A Framework To Select A Uniquely Appropriate Monte Carlo Success Threshold Target

Once a client’s willingness and ability to make course corrections to their financial plans have been assessed, advisors can identify the appropriate success/adjustment rate for Monte Carlo simulation purposes.

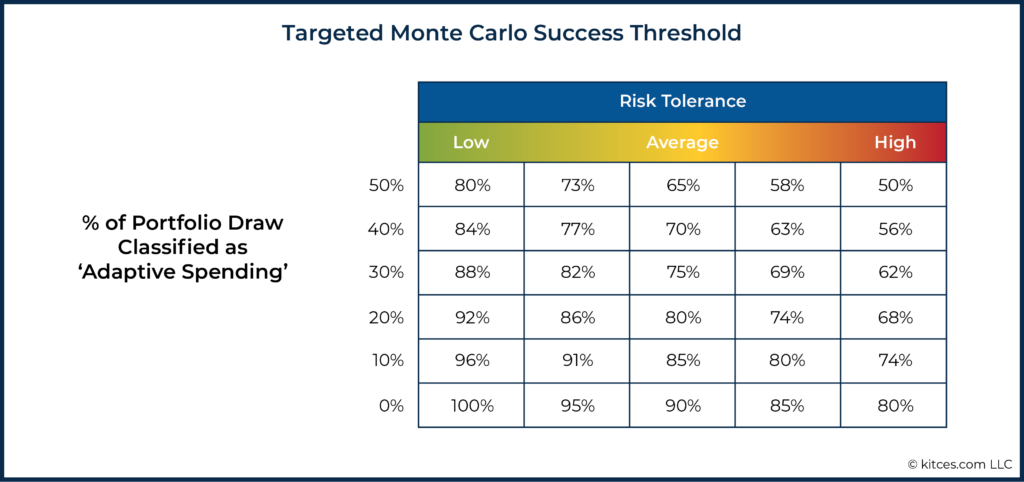

Advisors can take into consideration the client’s ability to make adjustments (represented by the “% of Portfolio Draw Classified As ‘Adaptive Spending’”) and their willingness to make adjustments (represented by “Risk Tolerance”) and run a Monte Carlo simulation with the appropriate target success threshold as identified in the table below.

Acknowledging that this is as much an art as science, the rationale for the success rates in the table above can be explained through the following extreme cases:

- Starting in the bottom left-hand corner (where a retiree will have a targeted Monte Carlo simulation success threshold of 100%), the retiree has no willingness (i.e., low risk tolerance) or ability (i.e., 0% portfolio draw classified as adaptive spending) to modify expenses in the face of an underperforming plan. This retiree conveys a desire to plan with ‘absolute certainty’ (or at least, wishes to spend so conservatively that even known potential market disruptions wouldn’t be anticipated to have any impact on their plan because their spending is already so conservative as to withstand it; in practice, this might be associated with a ~3% spending withdrawal rate).

- The opposite upper right-hand corner (50% targeted simulation success threshold) represents a retiree who has significant discretion in their portfolio draw (i.e., 50%) and a high willingness (i.e., high risk tolerance) to adjust expenses on an ongoing basis. For this retiree, a 50% retirement success probability, despite that this may sound unacceptably low, can actually be a viable target because it simply means a high (50%) likelihood they’ll need to reduce the spending they already acknowledged they can and are willing to reduce if necessary.

The two scenarios described above are, of course, representative of extreme situations, and are provided primarily as goalposts that help to illustrate the logic of the grid. The more likely use of this data will apply to retirees whose circumstances place them within these extreme scenarios.

Some practical examples of how this framework can be used include the following:

- Retirees entering retirement with large remaining fixed expenses, such as a mortgage, who are more susceptible to sequence-of-return risk. Advisors recognizing that these clients have a lower adaptive spending capacity can use this framework to advise for planning at more conservative success rates.

- Retirees with long-term planning horizons, where age plays a large factor in expense flexibility. For instance, retirees in their 60s, on average, are going to have far more spending flexibility than those in their 80s. As a result, the appropriate Monte Carlo success threshold is likely to be an evolving variable over time, just like the rest of the financial plan. As retirees age and expenses turn from adaptive to fixed, planning success thresholds should rise.

- Retirees who need to make pension decisions. Consider the example below, which illustrates how unique options can be evaluated to determine the best Monte Carlo success probability targets for each situation:

Example: Mary is a retiree with a $1M pension and a $1M investment portfolio. She has been given the option to either take a $50,000 annual pension distribution or move the $1M pension balance to her investment portfolio in a lump-sum payout.

Mary receives annual Social Security income of $30,000 and spends $120,000 a year. Her spending consists of $100,000 in fixed expenses and $20,000 in adaptable expenses.

Mary’s financial advisor uses a customized Monte Carlo analysis to evaluate her options, and with a good understanding of Mary’s adaptive spending capacity and risk tolerance (she has determined that Mary has an average risk tolerance), she calculates the appropriate Monte Carlo success rate target for each option as follows:

- Annual Distribution Option: If Mary selects the annual pension distributions, she will have $30,000 (Social Security) + $50,000 (pension distribution) = $80,000 in guaranteed annual income.

This means that Mary would need an annual distribution from her $1M investment portfolio of $120,000 (total spending need) – $80,000 (guaranteed pension + Social Security) = $40,000.

Since $20,000 of Mary’s expenses are adaptive, her “Percentage of Portfolio Draw Classified as ‘Adaptive Spending’” would be $20,000 (adaptive expenses) ÷ $40,000 (total portfolio distribution) = 50%.

At an average risk tolerance, Mary’s advisor models this planning scenario with a success rate target of 65%.

- Lump-Sum Payout Option: If Mary selects the lump-sum distribution, she will have $30,000 in guaranteed income from Social Security and will need $90,000 a year from her $2M investment portfolio (supplemented with the $1M pension lump-sum distribution).

In this case, Mary’s “Percentage of Portfolio Draw Classified as ‘Adaptive Spending’” is $20,000 (adaptive expenses) ÷ $90,000 (total portfolio distribution) = 22%.

At an average risk tolerance, Mary’s advisor models this planning scenario with a success rate target closer to 80%.

Using a framework that relies on customized Monte Carlo success thresholds can help advisors refine their methods of risk management, offering a personalized modeling strategy to use with clients, as well as an opportunity to improve the quality and effectiveness of their risk management services. Furthermore, analyses designed to fit the unique needs of each client can potentially improve outcomes and prepare clients for the possibility that future market returns may not be sufficient to meet their goals (and the actions they’ll need to take to get back on track).

This exercise can be helpful for clients, allowing them to envision more precisely what types of actions they can leverage to get back on track, versus simply focusing conversations on reactive strategies in response to variables that are beyond the client’s control. More personalized planning strategies can be especially reassuring for retirees when they see that they do have some degree of control over their outcomes even when markets may not cooperate, and for advisors themselves, who can rely on a systematic method for easily adjusting target success thresholds.

While using overly conservative Monte Carlo success rates for clients in the spirit of “first doing no harm” is not necessarily beneficial for all clients – especially for those with higher risk-tolerance levels who can be detrimentally impacted by overly conservative planning – every advisor will have a different comfort level as to the appropriate Monte Carlo success rate they utilize on average. Simply acknowledging that each client can plan with a different success threshold is a step in the right direction of using more customized planning strategies.

Ultimately, by adopting a service model for clients that offers robust quantitative methods (such as Monte Carlo analyses) and that is based on a client’s unique needs and circumstances, advisors can powerfully demonstrate their value to clients by using not just their requisite technical knowledge and experience to design good financial plans, but also their discerning wisdom to understand how the client’s subjective values and life goals are of paramount importance throughout the process!

Fantastic paper

Agreed!

Well done. Opening up the conversation to Adaptive Spending highlights the importance of what happens in the first 10 years of retirement (the “Go” period) having the most effect of a sustainable retirement compared to the remaining periods of retirement (the “Slow-Go” and the “No-Go”).

We’re testing Income Laboratory which looks promising implementing a cut/raise strategy but it’s not there yet. Meanwhile, we’re trying to use MGP. We want to be able to tell a client if their portfolio goes down to X, we need a 5% cut in spending or if their portfolio goes up to Y, we’re giving them a 5% raise. This article does a great explaining a good starting place for POS for a given client. We’re trying to see if we can nail down a change in POS that will require a 5% cut/raise to bring it back to target. Thoughts?

Is your cut/raise amount fixed at 5%? Or is the rate of change in spending dynamic depending on circumstances (e.g., size of market drawdown)?

That’s a good question. We want to be able to articulate something simple and quantifiable. The 5% cut/raise is the default spending change Income Laboratory uses and we like it, nothing radical. Because most of our clients have a small pension plus SS, it represents a larger, more meaningful cut in portfolio withdrawal rate. The dynamic part comes in the probability of a cut/raise ie, starting with a lower POS increases the probability of a 5% spending cut. We like that aspect because it allows the client to decide whether they are more likely to cut or raise in the future.

IMO Income lab is a great solution for implementing a strategy like this in a scalable manner. My favorite part of this article is framing discretionary expenses adaptive expenses.

Is the assumption here that if there is a market pullback and during the annual review a monte carlo success drops below an acceptable probability (80% is acceptable and goes to 75%) that we would then cut to a spending level that gets a client back to 80%?