Executive Summary

The idea of having investments be influenced by one’s values and a desire to advance the social good (in addition to personal profits) is not new, but in recent decades there has been substantial growth in various forms of socially responsible investing (SRI) strategies. However, given the relatively limited number of SRI funds in the marketplace, investors haven’t had a lot to choose from, and the nature of buying an SRI fund or not means the investor is either all-in or all-out for the strategy (at least with that particular portion of the allocation).

Yet with the recent launch of Morningstar Sustainability Ratings, in partnership with Sustainalytics, it now becomes feasible to not just “buy an SRI fund” (or not), but to tilt any portfolio towards sustainable investing, simply by choosing the most sustainable of the available choices in any investment category. With Morningstar’s Sustainability Rating applied to upwards of 20,000 different funds (both mutual funds and ETFs), the investor (or advisor) can screen out the lowest-rated 1- and 2-globe funds, or focus exclusively on the 4- or 5-globe funds (given the 1-to-5 globe rating system).

In fact, the raw Morningstar Sustainability Scores actually reveal that some non-SRI funds are just as sustainably invested as their SRI counterparts, when drilling down to look at the underlying holdings. Despite the explicit sustainability mandate, the funds are nonetheless buying companies that align to relevant environment, social, and governance (ESG) factors anyway – ostensibly because some fund managers (directly or indirectly) find those to be good investment criteria, anyway.

Yet with more investors seeking out sustainable investing – particularly amongst the rising Millennial generation – and the potential to use Morningstar Sustainability Ratings to tilt any portfolio towards sustainable investing simply by using the number of globes as a screen, it suddenly becomes possible for sustainable investing to actually begin to influence markets in the aggregate. After all, as the growth of Morningstar style boxes and their supporting benchmarks have shown, a common “scoring system” for investors to assess outcomes can have a significant impact on fund manager behavior. In turn, if dollars shift more towards sustainable investing strategies – even by just tilting at the margin – it gives fund managers more capital to deploy to companies that score well on ESG factors, and draws capital away from the rest, which means corporate leadership may finally have the incentive it needs to truly behave in a more socially responsible manner?

The Rise Of Sustainable Responsible Impact (SRI) Investing

The recent decades have witnessed a slow but steady rise for an investing approach that goes beyond “just” investing for maximal return, and instead focuses on a combination of both generating long-term competitive returns, while also trying to bring about a positive societal impact.

Early on, this approach of being a “Socially Responsible” Investor most commonly meant avoiding investments into companies whose products were of questionable moral or ethical character – which depending on the perspective of the investor, might have included “sin” or “vice” stocks (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, gambling), weapons makers, or environmentally unfriendly companies (e.g., fossil fuel energy companies).

Over the years, the socially responsible investing (SRI) approach shifted from “just” seeking to avoid companies that were perceived as adverse to the public good, to outright searching for investment opportunities that contributed to the positive, particularly environmental sustainability, leading to a rise of “sustainable investing” approaches that screen proactively for a wide range of positive environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors.

And in just the past decade, the approach shifted further from merely avoiding negative-impact companies and identifying environmentally sustainable ones, to more proactively seeking out positive-society-impact investing opportunities. Now broadly dubbed “impact investing” – a phrase coined in 2007 by the Rockefeller Foundation – the approach most commonly focuses on investing into new(er) companies trying to tackle private market problems with a balance towards doing both investing good and public good (as contrasted with SRI and sustainable investing approaches, which often focused on allocating capital to existing [publicly traded] companies).

With the continued growth of interest in – and outright dollar flows to – these various forms of socially responsible investing, sustainable investing, and impact investing, the collective SRI space itself has now re-appropriated the “SRI” label from being “Socially Responsible Investing” to “Sustainable, Responsible, Impact” Investing instead, or Sustainable Investing for short.

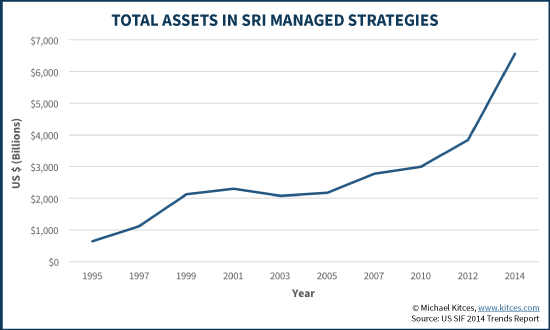

Notably, there has been a dramatic uptick in interest for sustainable investing in recent years (with the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investing estimating that total dollars being invested with some form of sustainability overlay jumped nearly 70% from just 2012 to 2014, and now adding up to more than $6 trillion). In part, the growth seems to be attributable simply to the growing awareness of SRI strategies and their availability. Demographic trends are perhaps beginning to play a role, too, as Millennials in particular are expressing far more interest in sustainable investing than prior generations of investors. Though as sustainable investing is becoming more accessible, some advisors are even finding interest amongst Baby Boomer clients, too.

And this growth has occurred despite the jury still being out about whether SRI investing is imposing a “cost” in terms of expected returns – given that the nature of screening out socially irresponsible companies and focusing on positive impact investing and high-ESG businesses will narrow the available investment universe and “limit” investment choices – with studies finding evidence of both higher and lower returns, and some debating whether periods of underperformance or outperformance of SRI strategies are simply driven by the relative under- or out-performance of underlying conventional investment factors that SRI happens to be more exposed to (e.g., disproportionate tilts towards higher beta or certain sectors).

Arguably, though, one of the greatest challenges to widespread adoption of sustainable investing was/is simply that it’s difficult to construct SRI portfolios, requiring an intensive process of analyzing companies and constructing portfolios from what’s left based on SRI screens and ESG factors. While there are a (growing) number of SRI mutual funds to do this work on behalf of the investor, their binary nature – you either buy an SRI fund, or you don’t – has meant SRI investing decisions were typically all-in or all-out. The tools have been limited to construct portfolios that merely ‘tilt’ in favor of more SRI-oriented companies or funds, without going all-in to dedicated SRI investment managers. Until now.

What Are Morningstar Sustainability Ratings

Earlier this year, Morningstar announced a new “Sustainability Rating” system to score more than 20,000 funds (both mutual funds and ETFs) based on their effectiveness across a wide range of Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors.

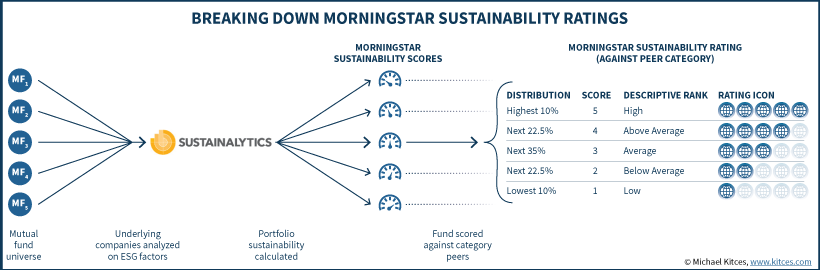

The scoring is done by drilling down to the holdings of the fund itself, and looking at each of the underlying companies one by one to identify its company-level ESG score (drawn from Sustainalytics, an independent provider of sustainability research and analytics). Any fund where at least 50% of its total assets are invested in companies covered by Sustainalytics will receive a Morningstar Sustainability Score. And notably, any fund (mutual fund or exchange-traded fund) where at least half of its assets are in companies that Sustainalytics tracks will be scored; Morningstar’s system is not a “pay-to-play” sustainability rating.

The fund’s Sustainability Score itself is a combination of both the (asset-weighted average of) Sustainalytics scores of the companies, with a further deduction made for any companies involved in “controversial incidents” (e.g., environment accidents, fraud, discriminatory behavior, etc.).

The Morningstar Sustainability Score for a fund is then compared to other fund peers in the same Morningstar category, to assign a Morningstar Sustainability Rating. Sustainability Ratings will vary from “Low” to “High” on a 1-to-5 scale, represented by the number of “globes” the fund receives. Thus, a 5-globe fund would have a “high” sustainability rating, a 3-globe fund would have an “average” rating, and a 1-globe fund would have a low sustainability rating. Notably, this means that the Sustainability Score is calculated on an absolute basis (from the ESG scores of the underlying companies), but the Sustainability Rating is based on a (relative) comparison to category peers.

In fact, to ensure a distribution of high and low sustainability ratings in each fund category, Morningstar assigns the globe ratings relative to all the funds in that category. The bottom 10% receive 1 globe, the next 22.5% receive 2 globes, the middle 35% receive 3 globes, the next 22.5% get 4 globes, and the top 10% are 5-globe funds. Notably, because the Sustainability Rating of a fund is applied relative to its category peers, a 5-globe fund in one fund category could actually have a lower absolute sustainability score than a 3-globe fund in another category that has a higher overall average. In other words, Morningstar’s Sustainability Ratings are about the relative sustainability within the category, not at an absolute level across all possible funds.

Potential Uses Of Morningstar Sustainability Ratings

So given that there’s already a universe of sustainable investing funds, including several well-known SRI fund families like Calvert, Parnassus, Domini, and Pax World, what’s the significance of analyzing investments using Morningstar’s Sustainability Ratings? Especially when – as you’d expect and hope – virtually all of today’s recognized SRI funds really do earn 5-globe ratings from Morningstar already.

The problem in large part is that while a number of companies are managed to be socially responsible, and a growing volume of private investment strategies pursue various forms of SRI investing to buy those companies, Morningstar estimates that only about 2% of the fund universe is comprised of SRI funds. Which means, as noted earlier, most investors can either go “all-in” on picking SRI funds, or not… and thus far, few investors have been voting to go all-in on SRI. In the meantime, there’s been little ability to simply ‘tilt’ portfolios towards SRI-favorable investments.

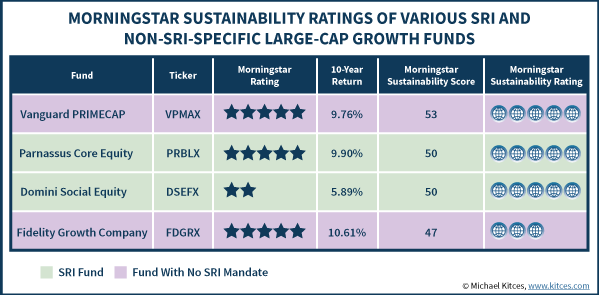

For instance, in the category of large-cap growth funds with strong track records and long manager tenure, both Fidelity Growth Company (FDGRX) and Vanguard PRIMECAP (VPMAX) are reputable players, with 5-star performance from Morningstar (averaging 10.61% and 9.76%, respectively, over the past 10-year market cycle, through the end of August 2016). However, Fidelity Growth Company is a 3-globe fund, while Vanguard PRIMECAP is a 5-globe fund, under Morningstar’s Sustainability Ratings. Which means an investor who was otherwise uncertain of which fund to choose based on its investment strategy and track record alone, might tilt towards PRIMECAP simply because, while it doesn’t have an explicit sustainability investing mandate, it is nonetheless more sustainably invested. Similarly, in the large-cap value space, both MFS Large Cap Value (ILVAX) and American Century Equity-Income (ACIIX) have strong 5-star performance track records from long-standing fund managers… but the MFS fund only receives 3 globes, compared to American Century’s 5-globe Sustainability Rating.

Notably, because the Sustainability Ratings are all scored relative to other funds in the category, it’s feasible for the investor to create a relatively more sustainable portfolio (from the same target asset classes or categories) without concentrating the fund into or out of certain industries and sectors (which can otherwise happen, given that certain sectors like energy contain a disproportionately high number of companies with potentially adverse environmental impact). In other words, rather than choosing from a small subset of SRI funds, which potentially have certain sector concentrations, it’s now possible to choose the most SRI-friendly from otherwise “standard” diversification choices amongst large-cap growth, large-cap value, mid-cap, etc. (Though notably, many small-cap companies are too small to be rated by Sustainalytics, and thus many small-cap funds have no sustainability rating from Morningstar.)

In addition, the reality is that while Morningstar’s Sustainability Ratings do affirm that most SRI-focused funds really are implementing sustainable investing strategies (i.e., they really do score as 5-globe funds), their absolute sustainability score in many cases is not actually any higher than some not-specifically-SRI funds! For instance, Vanguard PRIMECAP (VPMAX) actually has a higher sustainability score (53) than the Domini Social Equity Fund (DSEFX) or Parnassus Core Equity (PRBLX) (which both have a sustainability score of 50).

In other words, the Morningstar Sustainability Ratings make it possible to either identify the subset of otherwise-desired funds that also have high sustainability ratings (e.g., 4- and 5-globe funds), or alternatively to screen out especially poor sustainability funds (e.g., those with only 1 or 2 globes), without being forced to “pick an SRI fund” or not. This makes it feasible for the advisor to tilt the portfolio towards the funds that choose more sustainable companies in each category, and in some cases to even pick “non-SRI” funds that are just as sustainable as those with a sustainability mandate.

In addition, because Morningstar also includes the raw Sustainability Score (in addition to the category-specific Sustainability Rating), it is also possible to craft a portfolio that does target a high absolute level of sustainable investing as well (e.g., just picking the highest sustainability scores, regardless of fund category or style box).

How Morningstar Sustainability Ratings Could Move Markets

Ultimately, Morningstar Sustainability Ratings are a big deal, because it shifts sustainable investing from a “niche” style that requires specialized funds and managers, to one that is more accessible to a far wider range of prospective investors. After all, the reality is now that almost anyone can implement at least a sustainable investing “tilt” to their portfolio. Just start screening out the 1-globe and 2-globe funds, or lean towards the 4-globe or 5-globe funds, anytime the available investment choices are otherwise close.

In fact, it’s not hard to imagine new investing platforms or solutions that could crop up, to further leverage sustainability ratings. Advisors could easily roll out and advertise “sustainable” versions of their investment strategies, implemented by screening out low-globe funds in the portfolio. A new crop of “sustainable investing” asset managers could appear, who don’t pick the individual ESG-friendly companies (as most SRI managers do today), but instead assemble portfolios of sustainable investing (high-globe) funds (which perhaps will become a new category of managed-ETF strategies?). And third-party platforms may emerge to further leverage sustainability ratings to craft portfolios – for instance, Motifs comprised of high-globe funds, or a Quantopian strategy that trades ETFs based on their sustainability ratings (and how they change over time). Simply put, it’s far more feasible to craft sustainable investment strategies and algorithms to run them, once there’s a “standardized” scoring system to use.

And with the potential for this to be done systematically, and by an increasing number of investors – given the demographic trends towards Millennials and their commonly expressed preference for more sustainable investing strategies – it’s actually possible that Morningstar Sustainability Ratings could begin to move markets. After all, when in the aggregate a material number of investors shift their fund preferences towards more sustainable-investing-oriented fund managers (whether part of their stated investment objectives or just an outcome of them), and those managers in turn have more capital to deploy (to companies that score favorably on ESG factors), then socially responsible companies actually end out with better access to capital markets and an incentive to engage in better corporate governance.

In other words, when Morningstar Sustainability Ratings make it easier for investors to allocate capital towards companies that advance the public good and away from those that do not – as measured and “scored” by Morningstar and Sustainalytics – it allows capital markets to exert a force on corporate decisions in a positive manner (and without trying to ‘force’ it with regulation). And lest anyone question whether a “simple” Morningstar system could ultimately have that much impact on the decisions of managers, just look at how benchmarking fund manager behavior to Morningstar style boxes has impacted the behavior of those managers over the past several decades. Be careful not to underestimate the consequences of how having a clear “scoring system” can impact investor (and manager) behavior! (Though notably, a near-term rise in sustainable investing could actually trigger an over-concentration of dollars into a subset of more socially responsible companies, potentially distorting their market prices in the near term?)

Of course, all of these outcomes still rely on a desire of investors to actually pursue more sustainable investing strategies, when the evidence of whether SRI actually enhances long-term returns is still mixed. Nonetheless, the reality is that sustainable investing doesn’t actually have to increase returns for investors to decide to adopt it. If sustainable investing merely doesn’t hurt returns – which appears to be supported by a growing volume of research – while also accomplishing the secondary goal of improving the public good (in non-financial terms), that’s still a plus for investors who are concerned about such issues. Not to mention the subset of investors who believe that sustainable investing is literally more sustainable – financially and non-financially – in the long run, and will invest that way because they believe the long-term outcome will be more favorable, even if the statistics can’t definitively prove (or disprove) it yet.

And so the question remains: with Morningstar Sustainability Ratings making it easier than ever for investors to tilt portfolios in favor of sustainable investing, and investors in general (and Millennials in particular) expressing more interest in sustainable investing strategies, are markets on the cusp of a transition where pursuit of more sustainable companies will actually begin to influence capital markets and hold businesses more accountable for their environmental, social, and governance impacts?

So what do you think? Are you using the Morningstar Sustainability Ratings as a screen or search criteria when constructing portfolios? Are you thinking about doing so in the future, now that the ratings are available? What do you think the long-term impact will be? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Question Michael.

There is a marketplace of 2 investments trading on the secondary market.

One is a 5 year bond from a socially responsible saintly company paying 2% interest and trading at par.

The other is a 5 year bond of a diamond company that mines diamonds in Africa using coal powered equipment and miners who work 6 days a week for 16 hours a day at 12 cents an hour. They dump their runoff into the African water table. They may in fact be the least “socially responsible” company on Earth. This bond is paying 5% interest and for right now trading at par.

Both of these investments have the same credit rating.

Regardless of how many socially responsible investors there are that want to buy investment one, do you have any doubt that arbitragers will do anything, but bid investment 2 into parity with investment 1?

The same effect is true with equity its just more complicated.

So explain to me how you see this “moving markets” other than a way for Wall Street to charge do-gooders more money for their mutual funds?

Also explain to me how this changes anything for the companies involved. The bond or the stock was already offered to the public. It’s now on the secondary market. The proceeds of these transactions now go to the previous owner not the company.

Michael, I believe that the Morningstar ratings will be one of the arrows in the quiver of those who want to pursue Sustainability strategies, whether they are pursuing these goals for Social Responsibility goals/impact, or if the investor is doing so to attract new assets. However, there are more direct paths to being able to pursue portfolios that are more aligned with end investor values, including the IW Financial Workstation, the FinTech solution that we brought to market over a decade ago. Driven by explosive UN PRI signatory growth and the aforementioned Millenial attraction to such solutions, the uptake for solutions such as ours has grown substantially.

Would be pleased to provide more information if this topic is something that you expect to be developing over time.

“improving the public good” the preamble for every failed government program and dictator since the beginning of civilization.

How are these examples captured in ESG speak:

Apple, Microsoft, et al, continuing to provide software and hardware to countries that them it to retard human rights such as sexual orientation, women’s rights, child trafficking, drug trafficking, slavery, freedom of speech and privacy. However, the CEO of Apple can criticize citizens of Indiana for its religious freedom law.

Appliance makers whose products get “green approval” but the product life cycle is only 3-7 years compared with past “ungreen” products that lasted much longer. Is the shorter product cycle counted in the “green statistics” with regard to replacement impact on the environment? Doubt it.

Similar comments can be made on HVAC systems, Freon replacements require mandatory annual servicing and product lfie is 5-7 years for retail client.

Light bulbs, toilets; the sustainability con is riddled throughout our economy forcing us to step up and spend, spend spend. .

Is sustainable really about saving resources or is it a hidden sales and profit scam? If it is a scam then the ethics and governance is problematic.

Thanks for the post. Social responsibility is an ethical theory where people are responsible for their actions that have to benefit the society. I really like your list and thanks for the information.

Corporate responsibility