Executive Summary

Financial advisors create value for clients not only by giving good advice, but also by ensuring that the advice they give is actually implemented. After all, financial planning is worth a lot more to clients when they act on the advisor's recommendations (and realize the projected outcomes), in contrast to the advisor simply handing clients "The Plan" that is never actually implemented. And yet, getting clients to implement – even when they agree with the logic of the advisor's recommendations – is notoriously tricky, and despite many advisors' best efforts, some clients endlessly procrastinate, much to those advisors' frustration.

In this guest post, Derek Hagen, financial behavior expert and founder of financial therapy and life planning firm Money Health Solutions, explains why change (e.g., taking action on their financial plans) can be so difficult for some clients, how the resistance to change often stems from a client's ambivalence about whether to change at all, and how advisors can help clients work through that ambivalence through the technique of Motivational Interviewing (MI).

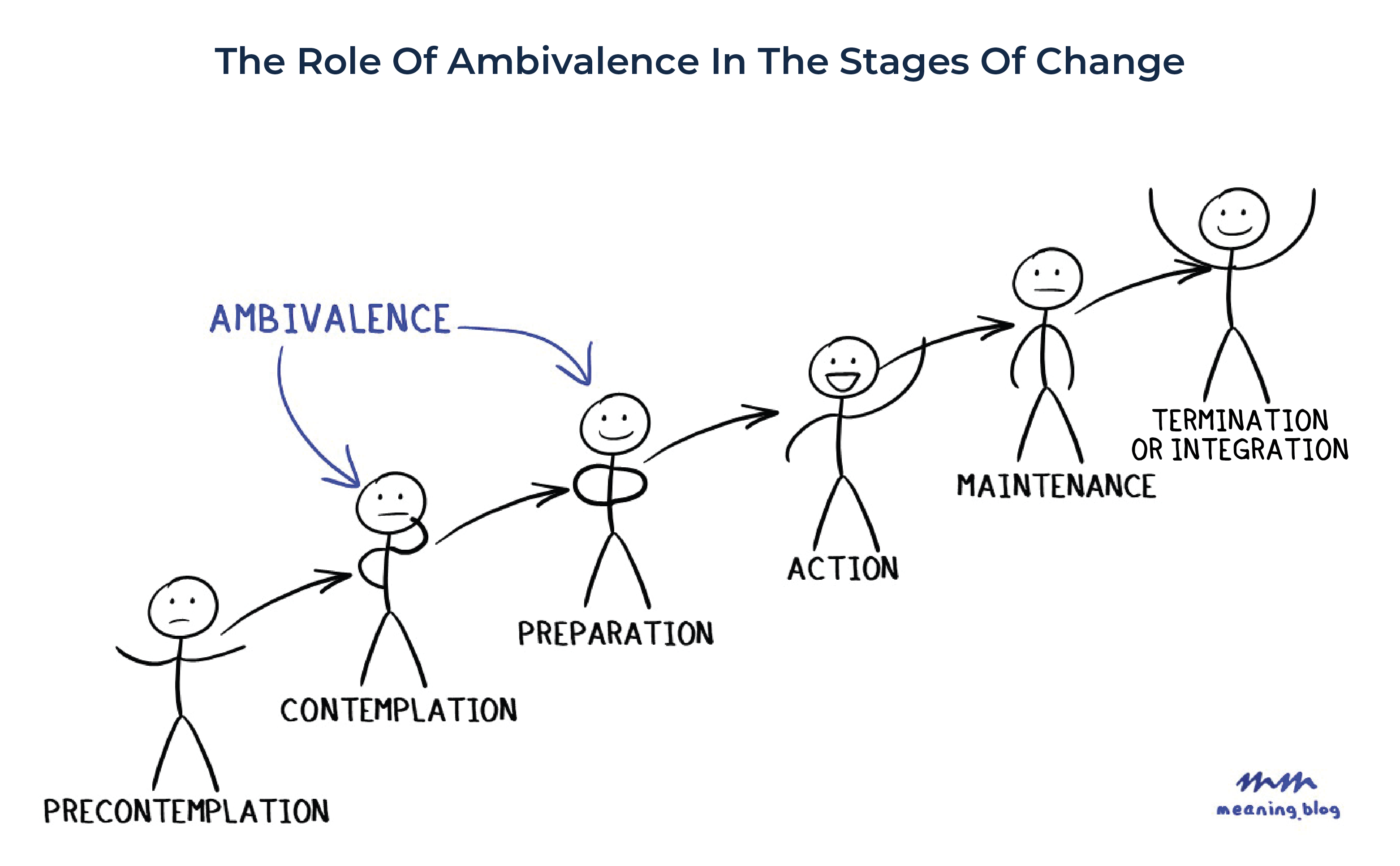

Psychologists have described the process of change through a series of 6 steps, starting before the person is even aware there is a change to be made, progressing through the stage of deciding to change, and then actually making the change. But the caveat is that, in the early stages of this process, the person is not yet ready to make the change: They're still ambivalent as they consider the benefits of changing and will often delay taking any action (sometimes indefinitely) until they've resolved this inner conflict.

Successfully resolving this ambivalence often depends on internally fueled motivation; as many advisors know, no amount of education or rational argument can usually convince an ambivalent client with little motivation to take action. Consequently, by focusing conversations with clients around change, advisors can help them tap into their own motivation to work through the ambivalence keeping them from taking action on their financial plan.

One technique for framing conversations around the change process is Motivational Interviewing (MI). Rather than attempting to convince a client to take action through numbers and logic, MI is focused on accepting and respecting the client's reasons for being hesitant to change and encouraging the client to develop their own reasons to move forward. MI encourages clients to express themselves without fear of being interrupted or misinterpreted, subsequently giving them the space to develop their own thoughts that give them the motivation to change.

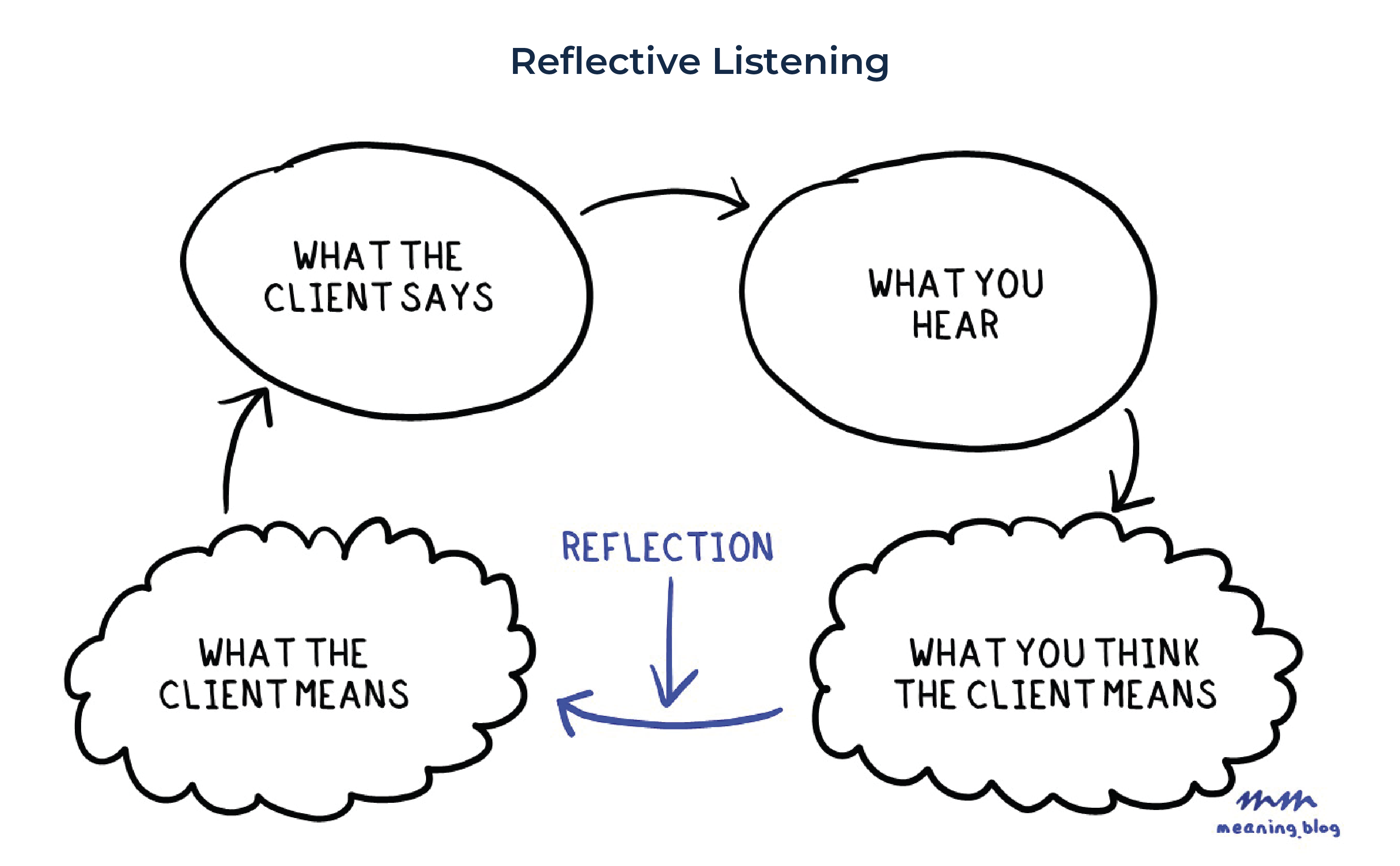

For example, a key skill of MI is reflective listening, where the listener repeats their own version of what the speaker has said when the speaker has stopped talking – which both ensures that the listener has understood and allows the speaker to clarify and/or continue with the line of thinking. Advisors can use different types of reflections to subtly reframe a client's thoughts in ways that encourage reassessment and exploration of new ideas – which can be what helps them finally break through the barrier of ambivalence and into readiness for change.

Ultimately, clients often come to advisors in the first place because, at least on some level, they are motivated to make a change. The key point, though, is that even though clients may desire change, their ambivalence may still be holding them back when the time comes to take action. Which means that getting clients to implement advice isn't (just) about convincing them about the 'right' course of action – it's about helping them prepare themselves to go beyond wanting to make a change and really feeling ready to make a change!

As financial advisors, we have the opportunity to play an important role in our clients’ lives. We can help clients make sound decisions and use their money in a way that supports a life that they find meaningful. This is an important role that we play, and clients are willing to pay for this advice. Yet it can be frustrating to see clients who pay us but who don’t implement our advice (even when they agree that the advice will be helpful and that they want to follow the advice).

While advisors often use several tools to persuade clients to implement the advice in their plans by reviewing the information, charts, graphs, and other data that support the logic of the recommendations, this information-based approach doesn’t always get clients to change. However, Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a different approach that advisors may find more impactful, as it involves a process that helps clients to collate their own motivation for implementing advice; clients literally talk themselves into implementing their own plan!

The Complexities Of Implementing Change

May financial advisors, and especially Financial Advicers, work within a fee-for-advice model whereby clients pay a fee in exchange for advice that they will then implement, sometimes with our help. This is how advice should work. It’s intuitive and makes sense. In fact, many financial advisors have extensive training on exactly how to go through the process of giving advice. CFP Board even sets forth a 7-step process for advisors to follow.

However, when it comes to the implementation phase, some clients don’t actually implement the advice they paid for, and this can be very frustrating for advisors. This could happen in a number of ways; the following are just a few examples:

- Withdrawing too much money from their portfolio at a rate that’s unsustainable.

- Not going to the estate planning attorney to draft or update estate planning documents.

- Not calling their insurance agent to start a new policy or cancel an old policy.

- Ignoring asset allocation recommendations by selling stocks whenever the markets are down or refusing to sell out of a concentrated stock position.

- Not consolidating loans or prioritizing debt repayment even when this is the best strategy for them.

- Making plans to retire when their plan indicates they would be better to work for a few more years.

- Remaining overly frugal even after you’ve shown them they have little chance of running out of money.

When advisors run into these situations, they often use an educational approach, turning to information and logic to persuade clients to implement the advice they are given. But when the problem persists despite the advisor’s attempts to guide their client in the right direction, some advisors get frustrated to the point where they begin thinking about firing the client. Some advisors might not feel like it’s the right thing to do to charge money for advice that isn’t being implemented, while other advisors may feel that clients who don’t implement their advice take up too much time and energy to justify keeping those clients engaged in a working relationship. Whatever the case may be, advisors often don’t look forward to meetings with these clients.

The frustration experienced by many advisors with clients who don’t implement the advice they are given is often because they don’t understand why clients aren’t implementing the advice. People should naturally want to implement change if they were to find a better way of doing things – this is intuitive, isn’t it? And clients come to advisors because of their own desire to make their lives better, which means that when advisors actually show them how to make their lives better, implementing the advice is a no-brainer… right?

Even though this may sound sensible, on some level we know this isn’t really how things work no matter how intuitive it may sound. Many of us know somebody who says they want to make a change but never do. This could be the smoker who hasn’t been able to quit, the person who made a New Year’s resolution to start an exercise program but hasn’t, or the unhappy spouse who knows they need to get out of their bad relationship but doesn’t.

What these examples all have in common is that the knowledge that change is needed isn’t enough for them to take action to make the change. In fact, there are a series of stages that are involved in the process of implementing change, and when individuals get stuck in one of the early stages of this process, actually realizing implementation may never happen at all!

The Process Of Change Occurs In Multiple Stages

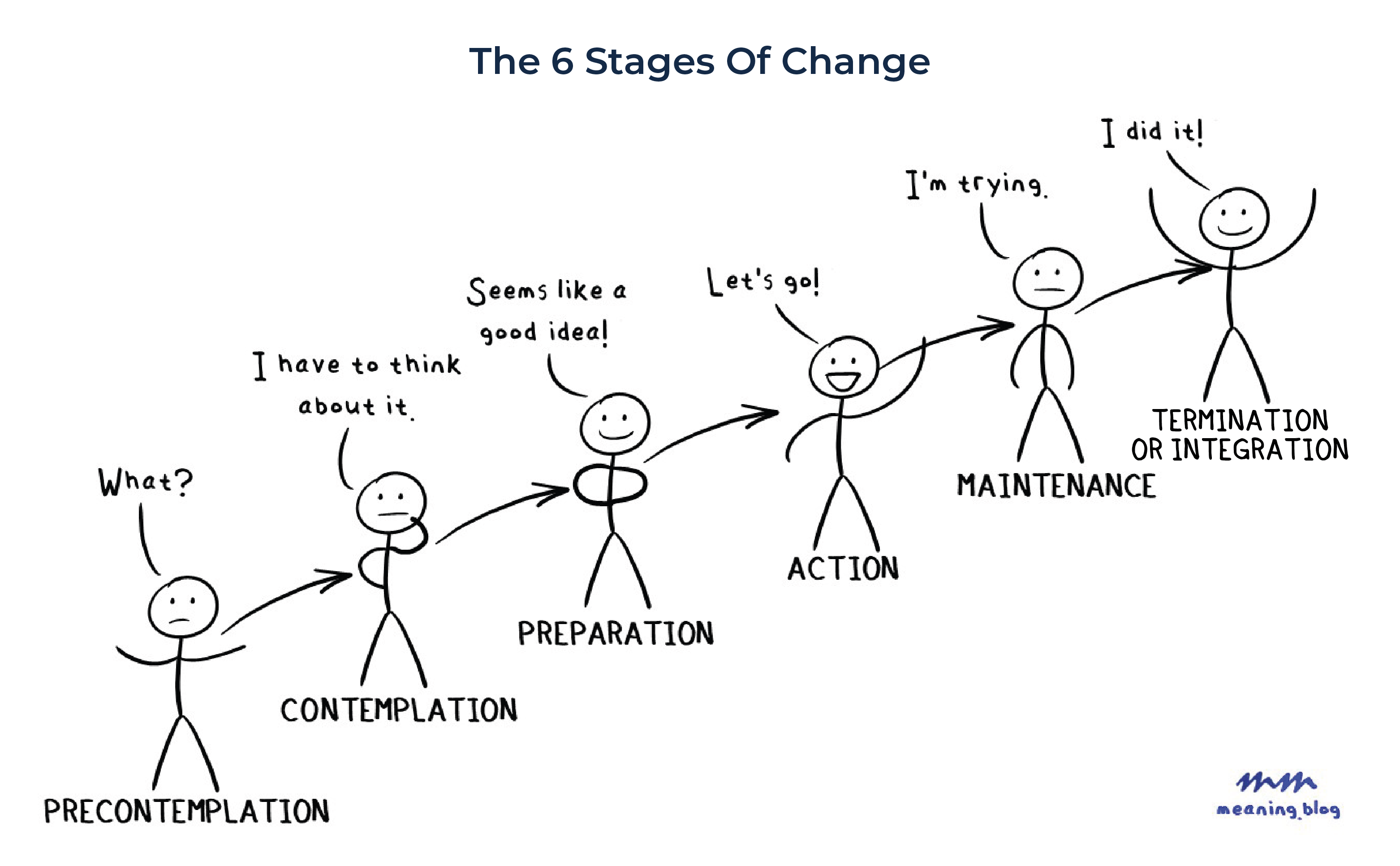

The reason that knowledge alone (i.e., knowing why a change is needed) isn’t enough for some people to make the change is that some people aren’t yet mentally or emotionally ready to commit to the change. According to the Transtheoretical Model of Change developed by James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente, the process of change involves 6 stages, consisting of the following:

- Precontemplation – when there is no awareness that a change can even be made;

- Contemplation – initial awareness that there is some change that can be made;

- Preparation – readiness to think about how change might be implemented and to research different ways to implement the change;

- Action – when an acceptable path forward has been identified and the individual is ready to go; and

- Maintenance – a commitment has been made to maintain the change that a person is trying to make.

- Termination (or Integration) – the process of change is complete, as new habits have been integrated with the person’s life.

For most financial advisors, the Action stage is where their favorite clients live. Unless a client is in the Action stage of change, they are far less likely to implement their advisor’s advice. Even clients in the Preparation stage are still researching options and considering their best path forward; they are generally not quite ready to commit to making a change. Thus, most of an advisor’s traditional tools (such as those offered by the CFP Board) work well for clients who are in the action stage.

Nerd Note:

There are several past articles that discuss how financial advisors can apply the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of Change to their own clients. “Helping Clients Get Unstuck And Follow Through By Understanding The Six Stages Of Change” gives an overview of the TTM process of change and discusses how advisors can help clients implement change that they may initially resist. “Helping Clients Change: From (Pre-)Contemplation To Implementation Action” offers ideas for advisors to help clients move beyond the "pre-contemplation" stage by raising their awareness of the changes that will improve their financial situation (and how to have conversations to work through resistance that can come up). And “Helping Clients To Stop ‘Thinking About It’ (Contemplation) And Start ‘Planning It’ (Preparation)” explains how advisors can guide clients from the Contemplation stage to the Preparation stage as they get ready to implement change.

Advisors Can Gain Insight Into A Client’s Stage Of Change By The Way They Talk

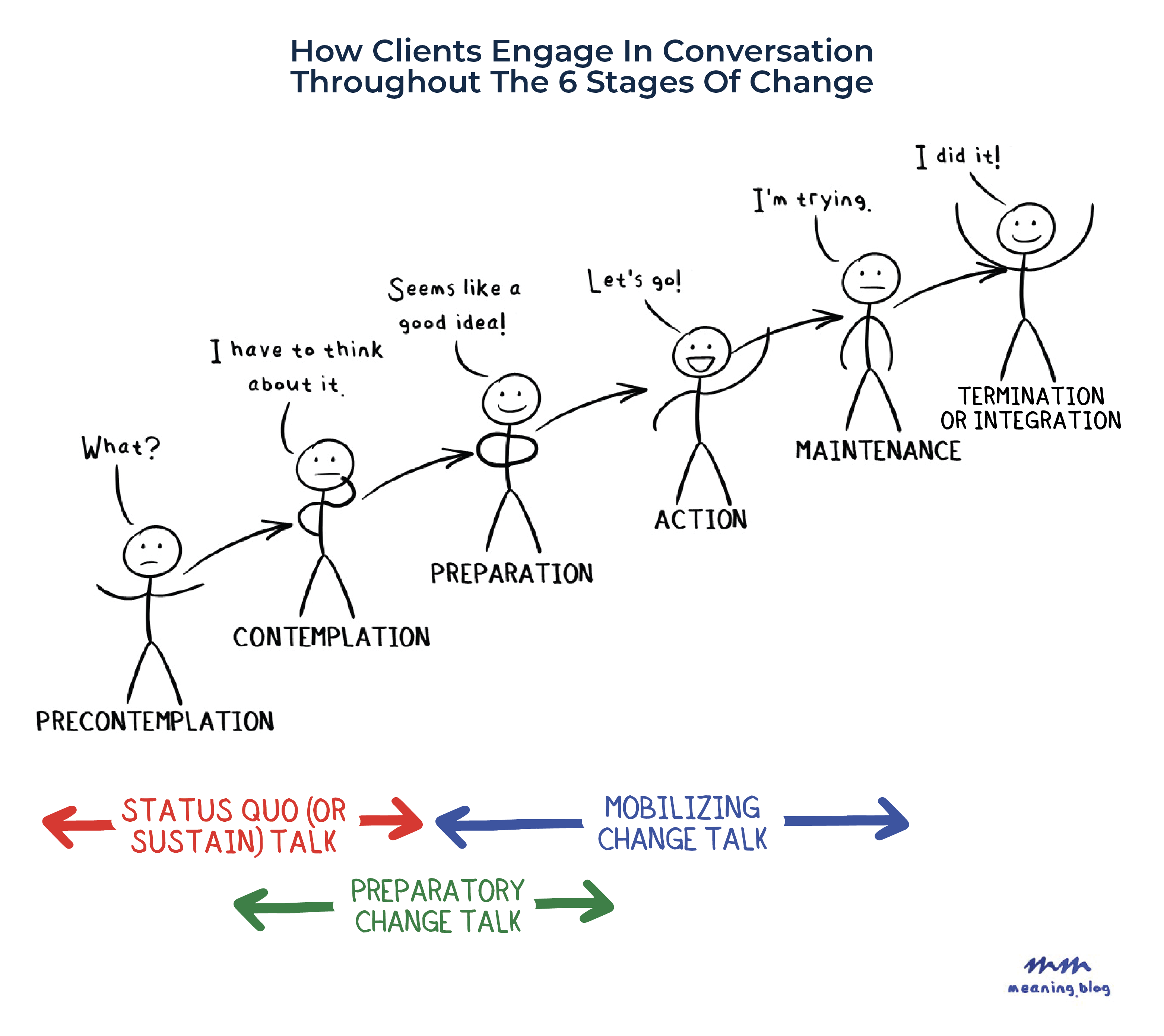

Change talk involves statements in favor of change, and the opposite of change talk is sustained talk, which involves statements in favor of the status quo.

Change talk that the client uses can sometimes offer a conservative signal about the stage of change they may presently be in. It can be broken down into 2 types: 1) preparatory change talk and 2) mobilizing change talk. Preparatory change talk will reflect a client’s desire to get ready for change, whereas mobilizing change talk will focus on getting ready to do something to move towards change.

Clients exhibiting no change talk and only status quo talk are likely to be in precontemplation or contemplation. Clients offering preparatory change talk are most likely in contemplation or preparation. Finally, mobilizing change talk is likely to be heard in the preparation, action, and maintenance stages of change.

Change talk can be thought of as self-motivational language, and learning to recognize it, and reflect back to the client, can help advisors better understand the client’s intention and motivation level. To do this, it can be helpful to understand the different subtypes of preparatory change talk (Desire, Ability, Reasons, and Need) and mobilizing change talk (Act, Commitment, Taking Steps), using the acronym DARN ACTS, which are described below.

DARN Preparatory Change Talk Subtypes

- D – Desire language indicates that clients want to change. It often has words like want, like, wish, or love:

- I really want to learn more about investing.

- I’d like it if I didn’t have to deal with this.

- I wish I could just not worry about my estate plan.

- I’d love to have my finances in order.

- A – Ability language indicates the client has competence in their ability to move forward. This will include words like can, could, able, and possible:

- I think I can overcome my past mistakes.

- If I set my mind to it, I could get it done.

- I think I’d be able to cut my spending so that I can contribute more to retirement.

- It’s possible for me to imagine selling that stock.

- R – Reason language describes the client’s specific reasons to change, and often include phrases that express a client’s particular motivations and aspirations:

- I’m tired of feeling stressed out about this.

- I don’t want to spend so much time doing this.

- This isn’t helping my family.

- I want to be a positive role model for my children.

- N – Need language often give clues to a client’s most immediate priorities. While need statements may not necessarily give specific reasons, there is a general sense of urgency and importance to them. Words that tend to show up are need to, have to, must, or got to:

- I need to get this figured out.

- I have to overcome this.

- I really must consider doing it.

- I’ve got to do something soon.

ACTS Mobilizing Change Talk Subtypes

- A – Activation language typically indicates that the client is almost willing to commit to moving forward but may not quite be there yet. They’re getting ready to think about changing. Typical words include willing to, plan to, and consider:

- I’m willing to explore those options.

- I plan to take a look at that information you gave me.

- I’ll consider a couple of these options.

- C – Commitment language is a step past Activation language. It represents a decision or commitment to do something, which is stronger than just being willing to do something. Words to listen for here include will, going to, or committed:

- I will call the estate planning attorney today.

- I’m going to choose one of these options by next time.

- I’m committed to making these phone calls this weekend.

- TS – Taking Steps is usually an indication that the client has entered the Action stage of change. At this stage, they are actually taking action and doing some of the things they need to do. Words commonly used here include started, reached out, and set up:

- I started gathering those documents.

- I reached out to the contact you gave me.

- I set up those automatic transfers.

Ambivalence And The Power Of Intrinsic Motivation

While information and education work are very effective tools to help those in the action stage implement change, individuals who are not in the Action stage are less likely to be motivated to implement change based on information or education alone. Which means that a key responsibility for advisors who want to give useful advice to their clients is to ensure that the client are in the Action stage first, before offering any advice. One of the most impactful ways that advisors can help clients get there is through motivation.

Motivation essentially comes in 2 general forms: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic motivation is motivation that lies outside of us. It can be generated through information, data, persuasion, logic, research, and peer pressure. These types of extrinsic motivators can work and they can sometimes get people to change, but often only in the short run. People who are extrinsically motivated usually don’t have a strong commitment to the changes they have made; they tend to change their mind for just about any reason. Which means that extrinsic motivators generally don’t work so well in the long run.

Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is the motivation that lies within us. Unlike extrinsic motivation, if we’re intrinsically motivated, external factors won’t impact our commitment to reach the goal we’ve set for ourselves. People who are intrinsically motivated want to change because they see the change as an important part of their identity and who they are. Which means that when clients feel challenged by or resistant to the recommendations that their advisors make, one of the best ways advisors can encourage them to implement advice is to help them find intrinsic motivation to do so.

Competing Forms Of Internal Motivation Give Rise To Ambivalence And Resistance To Change

The journey that a person takes to implement change often requires that they resolve conflicting feelings of wanting to keep things as they are (i.e., status quo bias) and wanting to change. This experience of wanting 2 (or more) things or having conflicting feelings about something at the same time is called ambivalence, and it effectively involves having competing motivations. Ambivalence often feels uncomfortable, yet it’s nearly a universally experienced human state of mind.

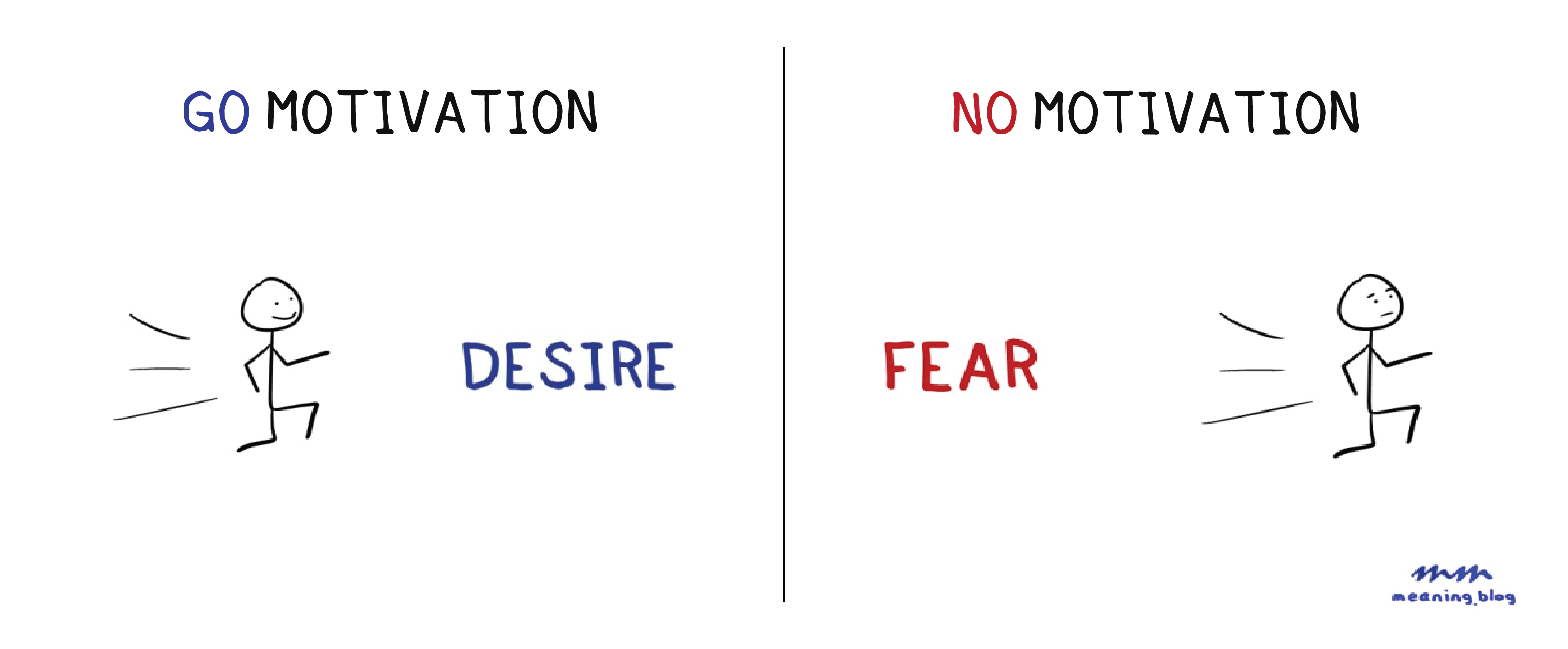

People can experience conflicting motivations of ambivalence in several ways, and can come in the form of emotions, thoughts, physical sensations, beliefs, or values. Some motivations can be positive and considered as “Go” motivations that push a person toward something. Others are negative and thought of as “No” motivations that drive a person away from something.

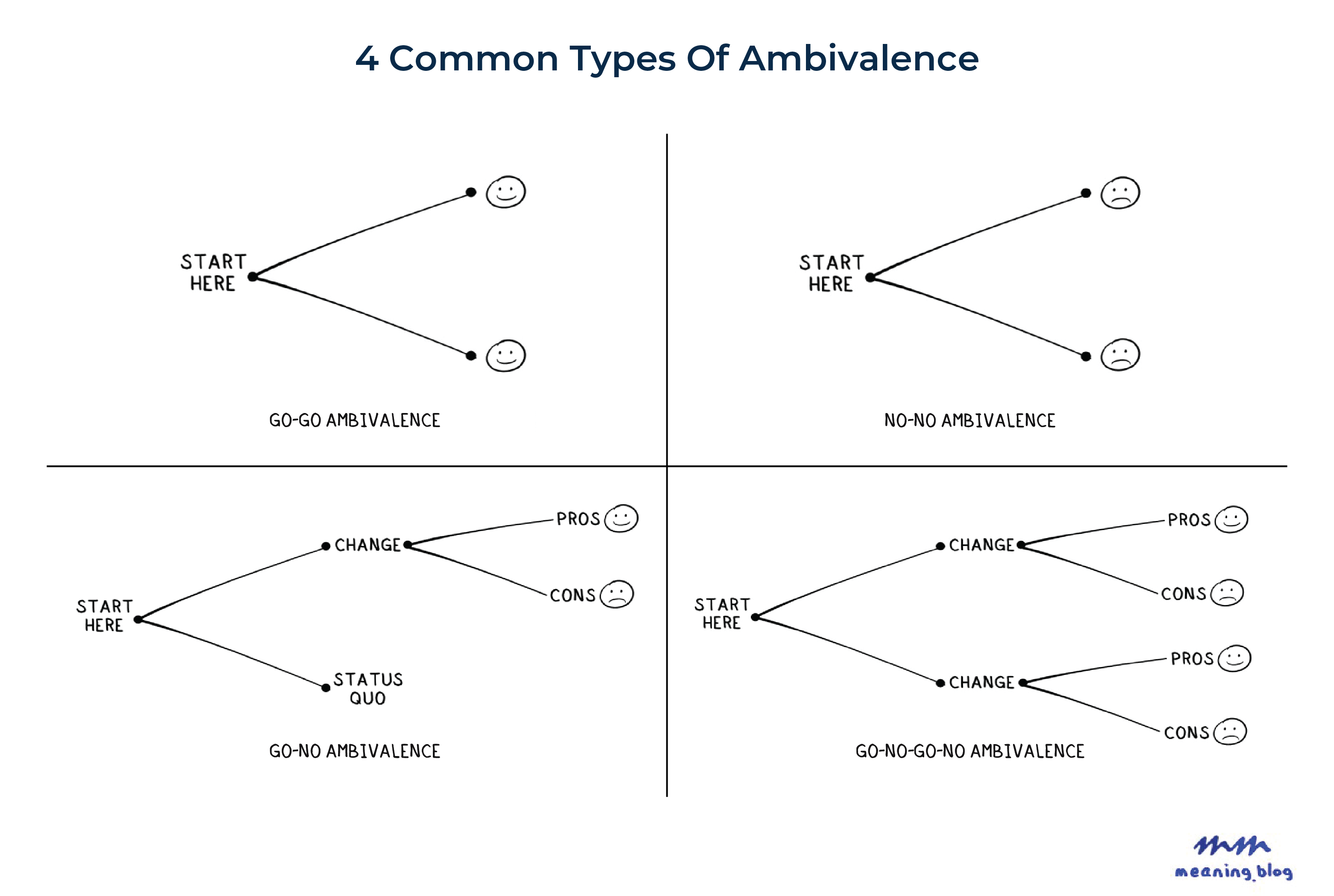

Interestingly, several Go and No motivations can occur at the same time, which can make a person feel as if they are simultaneously being pushed and pulled in different directions. 4 types of commonly experienced ambivalence include the following:

- Go-Go Ambivalence: This is when we have multiple options and all of them are good, but we can only choose 1. If ambivalence is ranked, this would be the best one to have.

- No-No Ambivalence: The opposite of Go-Go ambivalence, this involves having to choose between 2 or more options all of which are undesirable. This form of ambivalence is quite unpleasant because there are no good options, like being “stuck between a rock and a hard place” or having to make a Sophie’s Choice.

- Go-No Ambivalence: This will be the most familiar type of ambivalence to financial advisors because it involves either doing nothing, or making a decision that has both pros and cons associated with it, much like implementing your advice.

- Go-No-Go-No Ambivalence: This is much the same as Go-No Ambivalence, but with 2 (or more) choices to make. This is when a client is torn between multiple decisions, each of which comes with its own set of pros and cons.

The more a person digs deeper into ambivalence the more they realize that it’s necessary in order to implement change. In fact, in order to progress through the stages of change successfully, one must experience and overcome ambivalence first.

In the process of change, ambivalence tends to be experienced most frequently in both the Contemplation and Preparation stages of change. While people aren’t yet aware that there’s anything to change during the Precontemplation stage, becoming aware signals their entry into the Contemplation stage. And at this point, when they understand that there’s some change they can make, not only have they entered the contemplation stage of change, but they have also started to experience ambivalence.

And while status quo bias (i.e., a desire to keep things as they are) can be a strong “No” motivation with a pretty tight grip on a person in the Contemplation stage of change, there is still a part of them that is compelled by a “Go” motivation, which makes them curious about making a change.

Over time, the reasons to change may start to outweigh the reasons to stay the same, prompting the client to enter the Preparation stage of change. Yet, even though they may understand the value of change and even think about preparing to make the change (strong “Go” motivations), there is still part of them that is struggling with ambivalence and that wants to stay the same (“No motivation is still holding on tight).

Helping Clients Navigate Ambivalence Encourages Them To Reach The Action Stage Of Change

Ambivalent clients who keep an even balance between their competing motivations will often find it impossible to progress to the Action stage of change. If a client is ambivalent and somebody argues one side of their ambivalence, it’s common for the client to argue the other side of the ambivalence. You can usually tell this is happening when their statements start with “Yeah, but…”

For example, a client may be ambivalent about investing part of their savings into the stock market. If their advisor makes a case for investing the money, they might respond by saying, “Yeah, but I’m going to feel awful if the market goes down right after we do this. You’ve told me that’s possible. It’s like you’re not listening to me.” On the other hand, if a friend makes the case for saving the money, they might tell them, “Yeah, but I’ve always been told that I should make my money work for me; having it sitting in a savings account won’t do anything for me.”

In other words, advisors can’t really give advice to an ambivalent client and expect a productive outcome. And yet, this is an advisor’s job – they advise people to help them improve their financial lives. So when an ambivalent client argues in favor of the status quo to maintain their ambivalence, how can advisors leverage a client’s internal motivation and frame the discussion to help them change?

Motivational Interviewing Intrinsically Motivates Clients To Implement Financial Advice Themselves

There are a few different approaches that can intrinsically motivate clients and help them tackle ambivalence to help them reach their financial goals. For example, helping clients determine their financial purpose, connecting them with their personal values (using a Personal Values Card Sort Deck), and helping them revisit their money story are all ways that develop intrinsic “Go” motivation that help clients overcome the “No” motivation of status quo bias. Motivational Interviewing (MI) is another particularly impactful approach that advisors can take to tap into the intrinsic motivation that clients already have. One of the founders of MI, William Miller, defines it as a way of having a conversation about change and helping people provide their own motivation for change. It is a collaborative approach that empowers clients by recognizing their autonomy.

The Spirit And Methodology Of Motivational Interviewing (MI)

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is not a technique used to get people to do what they don’t want to do. Instead, the spirit of MI is grounded in the following important principles:

- Acceptance: MI is based on accepting what the client brings to the table without judgment, having an interest in their internal perspective, respecting their autonomy, and seeking to understand their strengths rather than what’s wrong with them.

- Collaboration: MI is not something that advisors do to clients, but rather something they do with or for MI is a collaboration between an advisor and the client; it recognizes that clients are the experts in themselves. Advisors may know more about financial matters, but they can never know more about clients than the clients themselves do.

- Compassion: MI prioritizes the client’s needs and promotes their well-being.

- Evocation: MI aims to draw out what clients already have within them. It focuses on identifying and helping them leverage their strengths and other positive aspects.

In addition to the 4 principles that guide the spirit of MI, there are also 4 general steps involved in MI as outlined below:

- Engaging: The engagement process is the foundation upon which the rest of MI work takes place. In this step, advisors emphasize that clients have the right to full autonomy and focus their attention on understanding the client’s perspective. This step is crucial to establish a strong alliance and to develop trust in the working relationship.

- Focusing: Deciding what to focus on in a relationship involves a process of choosing a direction to go together as a team (which can require a reiterative evaluation of the client’s priorities that are often revealed through any of the other MI steps). Most of the time, the focus for financial advisors is clear; the focus is on implementing sound advice.

- Evoking: This step involves eliciting the client’s motivations to change towards the focus that you have collaboratively come up with.

- Planning: Planning is the stage where recommendations are given and happens most effectively when clients have reached the Action stage of change.

MI is not a linear process and the steps above can be followed in whatever order or repeated in any way that feels most appropriate. While the Engaging step typically happens at the beginning of a client relationship, it may be helpful (and sometimes necessary!) to revisit this step later in the process to reengage with clients if they aren’t implementing the advice from their advisor. The Focusing and Evoking steps are typically used to move clients from the Contemplation and Preparation stages of change into the Action stage of change. Planning happens when they have reached the action stage and are ready to go.

The OARS Of Motivational Interviewing Engage And Focus Clients

The foundation of Motivational Interviewing (MI) lies in good listening skills, which encourages clients to express themselves without fear of interruption or misinterpretation. While most people think they are naturally good listeners (just like they think they are better-than-average drivers, funnier-than-average joke tellers, and better-than-average investors), the reality is that developing good listening skills take practice – they aren’t intuitive. In fact, our default mode is often to assume that we properly heard and interpreted what was said. However, in the words of William Miller, “It is not a good idea to respond to what you think the words you believe you heard meant.”

The key to good listening for financial advisors, then, is to find out whether their understanding of what a client meant is accurate. There are 4 core communication skills associated with Motivational Interviewing (MI) that help them accomplish this. These include Open-ended prompts, Affirmations, Reflections, and Summaries; these can be described by the acronym OARS.

Open-Ended Prompts

In contrast to a close-ended prompt (such as a yes-no question that limits an individual’s response), open-ended prompts invite a person to talk about what’s on their mind and to elaborate further on important points. Financial advisors don’t use open-ended prompts simply to gather information from a client to plug into a financial plan; instead, they are used to help advisors (and sometimes the client themselves) understand the client’s point of view and what they’ve got going on in their minds. Not only can this be an effective way to clarify the client’s priorities, but it can also be a valuable communication tool that helps to establish the spirit of MI (i.e., illustrating principles of acceptance, collaboration, compassion, and evocation, as discussed earlier) while engaging and developing rapport with the client.

While open-ended prompts can be introduced in the form of a question, they may be more effective to frame the prompt as a curious statement instead. For example, in his Exquisite Listening seminars, Ted Klontz, Director of the Financial Psychology Institute, incorporates MI (among other techniques) to help advisors develop communication skills that help deepen relationships and reduce conflict. In his workshops, he recommends avoiding questions altogether, because questions can often lead people to worry about giving a ‘wrong’ answer and hesitate, suspecting there’s a ‘right’ way they need to answer.

Open-ended prompts often require a good deal of thought, and a client’s response might reveal insights that surprise even the client themselves. Good open-ended prompts get to the heart of what advisors want to know, and often start with phrases such as “Tell me more about…”, “I’m curious about…”, “Say more about…”, or “I’d like to know…”. They welcome responders to share what’s on their mind without worrying about being right or wrong.

The trick is not to focus on asking a lot of clever questions – it’s more about using the right prompts that encourage the client to talk openly and share what they are thinking about with minimal reservation.

Affirmations

Affirmations bring attention to the good things that other people do. Noticing positive actions might sound easy, but it can sometimes be very difficult because of our natural susceptibility to negativity bias. We tend to notice the things that people aren’t doing well more easily than what they are doing well. Advisors can affirm things that clients have done well by acknowledging and commenting on the good aspects of the behavior involved.

For example, a client might tell their advisor that, although they scribbled down a couple of notes on a piece of paper, they didn’t get around to contacting their estate planning attorney. Affirming is to recognize that they spent some time putting some notes together and not focusing on what they didn’t do, which is not contact the estate planning attorney.

Reflections And Reflective Listening

Reflective listening is the main skill of MI. With reflective listening, the listener repeats (preferably) in their own words what they heard the speaker say, to ensure they understood what was said. At its core, reflections offer the listener’s guess about what they thought the speaker meant.

Reflections are not framed as interrogative questions that end in a question mark; instead, they’re offered as declarative statements that end in a period, with the inflection at the end of the statement going down. Consider the differences between the following reflections and how questions might be perceived differently by a client:

- Question: “The stock market makes you uncomfortable?”

- Reflection: “The stock market makes you uncomfortable.”

- Question: “You didn’t see your estate planning attorney?”

- Reflection: “You didn’t see your estate planning attorney.”

- Question: “You don’t see a problem with that?”

- Reflection: “You don’t see a problem with that.”

- Question: “You’re getting angry about this?”

- Reflection: “You’re getting angry about this.”

The differences between the sentences above reveal an important nuance: while questions run the risk of making the client feel defensive about their position, reflections simply offer a summary of what the client just said, giving them reassurance that the advisor is listening to them, and also the opportunity to make corrections in the case of misunderstanding.

In addition to reflecting on the content of what a client says, advisors can also reflect on the emotion that they believe is behind what a client is expressing. The main point is to encourage the client to keep talking; reflections are not meant to express the advisors own judgments or opinions.

Simple Reflections

Simple reflections often represent the biggest bang for the advisor’s buck in terms of what can be learned from the client. A simple reflection reassures the client that the advisor understands them. With a simple reflection, the advisor simply gives back to the client all or part of what they just said. They can paraphrase in their own words, but the important point is to reflect only the ideas that come from the client.

Client: I can’t believe my attorney charged me this much.

Advisor: You were charged more than you thought.

If an advisor reflects only part of what a client says, preferentially reflecting on some aspect of preparatory or mobilizing change talk (versus status quo or neutral talk) may align best with the spirit and methodology of MI by helping the client recognize their internal motivation for change and the most suitable direction for the client to take in implementing change.

Simple reflections don’t always have to reflect the words a client used. Advisors can also reflect back how the client expressed they are feeling.

Client: I can’t believe my attorney charged me this much.

Advisor: That makes you upset.

Complex Reflections

Simple reflections are a great starting point for advisors to use to let clients know that they understand them. However, complex reflections can offer more to the conversation by moving it forward, sometimes steering it towards the direction of change. They don’t precipitate big jumps in the conversation, just slight movements.

Continuing The Paragraph: One complex reflection that is especially useful in moving the conversation forward is called continuing the paragraph. With this type of reflection, the advisor takes a guess about the direction the client was going. You can use continuing the paragraph reflections to understand why your client said something. Consider the following example:

Client: I didn’t go see my estate planning attorney.

Advisor: It’s tough to think about what happens to your stuff after you pass away.

The point is not necessarily to guess correctly. If you are wrong, the client will correct you and then you get the true reason they didn’t go see their estate planning attorney. Perhaps they didn’t have time or something else came up.

Double-Sided Reflection: A complex reflection that is especially effective with ambivalent clients is a double-sided reflection. With a double-sided reflection, both sides of the client’s ambivalence are reflected so that they know that you understand how difficult their decision is. You might think of this in terms of ‘hands’, where one hand of the reflection can express one side of the client’s ambivalence, and the other hand addresses the second side of the ambivalence.

Notably, using the word “but” after reflecting the first side a double-sided reflection can give the impression that the first side of the reflection is being negated. For example, if an employer were to talk about all the good things an employee did well for the year, and then follow it with the word “but”, the good things don’t really matter as much anymore because the “but” effectively canceled them out.

Another approach to using double-sided reflections is to frame one side (or one hand) as the status-quo talk first and the other side/hand as the change talk. People tend to remember what was said last.

Client: I didn’t go see my estate planning attorney.

Advisor: You didn’t get a chance to see your attorney and at the same time you understand how important this is, and that tension feels a little uncomfortable.

Reframing: Another form of complex reflection is reframing. With the reframe, you reflect back what the client said but you do it with a different interpretation. You consider a different meaning to their perspective.

Client: I’ve tried all the solutions I can think of and none of them have worked.

Advisor: What I’m hearing you say is that you’re resourceful and persistent. Tell me more about that.

Amplified And Undershooting Reflections: Another form of complex reflection is an amplified reflection. An amplified reflection is considered “graduate-level” reflecting because you ought to get some practice with other reflections first. An amplified reflection is when you amplify, or exaggerate status quo talk so that the client will walk it back and decrease its importance. This has the potential to sound like sarcasm which is why it should only be used after you have had some practice. Consider the following example of an amplified reflection:

Client: I just never like the way my spouse spends money.

Advisor: Your spouse’s spending makes you furious.

Client: Well, not furious. Maybe just a little bit frustrated.

In the above dialogue, the advisor used an amplified reflection to get deeper into the client’s feelings and hoping that the client would notice their absolute language (e.g., “never”).

Whereas an amplified reflection can be thought of as overshooting the intensity of the client’s words, an undershooting reflection downplays the emotional intensity of what the client said. Undershooting has a higher likelihood of getting the client to continue exploring their thoughts and tell you more about it.

Client: I just never like the way my spouse spends money.

Advisor: Your spouse’s spending irks you a little bit.

Client: A little irked? It makes me mad that…

Summaries

Summaries are similar to reflections in that they reflect what the speaker just said, but they do so in a way that gives more feedback than a reflection. With a summary, the listener offers the speaker a recap of what they heard over the course of the last several minutes or over the course of the whole conversation, if longer, and lets the speaker hear a synopsis of everything they just said over a period of time.

The value of a good summary is that it conveys to the speaker that the listener was paying attention and successfully captured the importance of what the speaker was trying to communicate; this is in contrast with a reflection, in which the listener only repeats a single idea with the intent to confirm understanding.

It can be helpful after giving a summary for the listener to ask the speaker if there’s anything that they missed, or if there’s anything else the speaker wants to add. This gives them an opportunity to continue the conversation.

Summaries also give the client the opportunity to hear their words three times. They hear their words when they say it. They hear their words reflected back when you reflect their words. Then they hear their words again when you summarize what they said. These are their own words that they hear repeated, not yours or anybody else’s.

Motivational Interviewing Communication Tools To Evoke Clients Toward Change

Most clients who come to a financial advisor for help already have motivation to change... that’s why they become a client in the first place. However, many clients may be challenged by ambivalence; some may be overwhelmed with too many options while others may not have enough information to understand the outcomes of the actions they are considering.

Evoking is a central part of Motivational Interviewing (MI) and can help the advisor draw out a client’s intrinsic motivation to change. The advisor accomplishes this by inviting the client to engage them in change talk that they can then reflect back to the client. Ultimately, this helps the client realize and focus on their most important priorities, overcome their ambivalence, and take action on their financial plan.

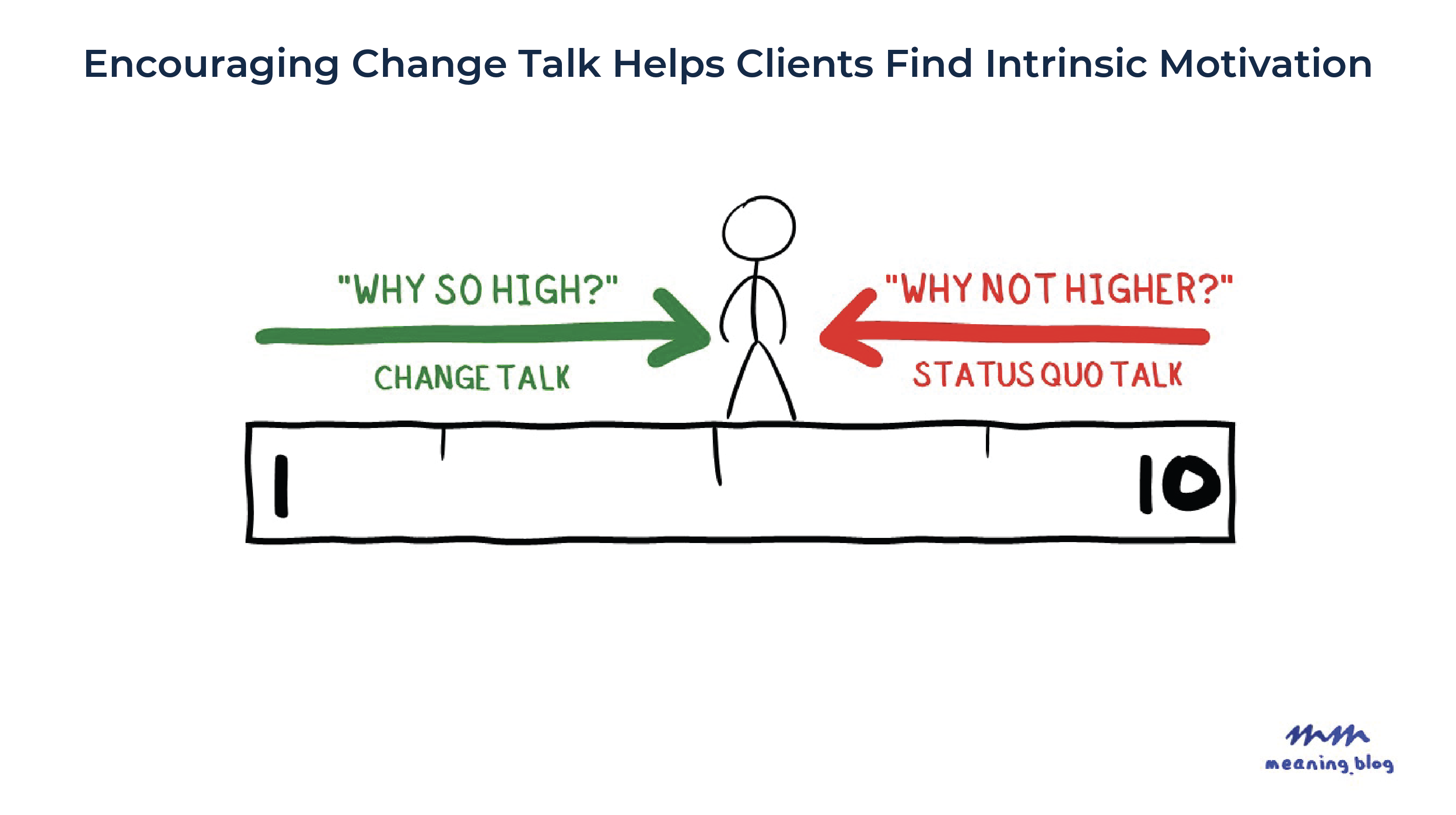

Scaling Questions

One simple tool that aims to evoke motivation is the scaling question. With scaling questions, an advisor would ask their client where they believe they are, on a scale from 1 to 10, in terms of how likely they are to change. 3 common ways to use these questions include asking about the importance of the action, the client’s readiness to start, and their confidence in their own ability to carry out the action.

- Importance Of Action: On a scale from 1 to 10 with one being completely unimportant and 10 being the most important thing you can prioritize, how important is it for you to do this right now?

- Readiness To Start: On a scale from 1 to 10 with one representing not being ready to do this right now and 10 representing being ready to go right away, how ready are you to do this?

- Confidence In Ability: If we assume you were going to do this, on a scale from 1 to 10 with 1 being a complete lack of confidence in your ability and 10 being perfectly confident in your ability, how confident are you that you could do this if you chose to?

The trick is that we don’t care about the absolute value. The number the client gives isn’t important. What is important is the next question asked, which would be, “Why is the number so high?” By asking why the number is so high you’re inviting them to tell you all of the reasons that they think it’s important, or that they’re ready to do it, or that they have confidence that they can do it.

Resist the urge to ask why it’s not higher. If you ask why it’s not higher, then you’re inviting them to tell you all the reasons they don’t think it’s important or that they’re not ready to do it or that they don’t think they can do it.

Importance, readiness, and confidence are just 3 of the more common ways to use scaling questions. Advisors can get creative with these and use a client’s unique situation to model specific questions. For example, if a client doesn’t want to sell a concentrated position in their portfolio, the advisor might ask, “On a scale 1 to 10, with 1 being you’re never going to sell the stock and 10 being we can start talking about it on Monday, where would you rate yourself?”

Scaling questions can also be used to gauge progress. This might sound like, “On a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing your financial life when we first started working together and 10 being your perfect ideal future, where would you say you are today?”

Asking the follow up question about why their numbers are so high gives clients an opportunity to talk about their motivation to change. This is motivation that’s already there, and the next step might be for the advisor to ask how they can help the client add to their motivation, or how they can help get them from the number they chose to half a step higher. For example, an advisor with a client who’s at a 6 could ask, “What would it take for me and my team to get you from a 6 to, say, a 6.5?”

Motivational interviewing techniques offer financial advisors a powerful way to help clients implement the advice they are given. By empowering clients to talk themselves into making positive change in implementing your advice, motivational Interviewing leverages a client’s intrinsic motivation by helping them overcome the challenges that come with ambivalence so that they can finally take action. By understanding the different stages of change and how the spirit of motivational interviewing principles helps clients prepare to take action, advisors can generate greater engagement, ultimately resulting in clients who successfully achieve their desired outcomes!

Leave a Reply