Executive Summary

In the midst of America’s Great Depression (which spanned from the October 1929 “Black Tuesday” stock market crash to the end of the 1930’s), President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted several “New Deal” programs to provide the country with relief (and to encourage recovery) from the poverty and high rates of unemployment facing Americans at the time. Social Security was (and remains) one of the most significant programs created as part of the New Deal, and was intended to protect Americans from the “hazards and vicissitudes of life”, offering them “general welfare” and “social insurance” through retirement income for those over age 65.

However, Social Security benefits were not initially available for state or local government employees because the institutions they worked for often managed their own retirement (pension) programs for employees. To address the concern that state/local government employees were ‘missing out’ on Social Security, and in part to allow states to shift a portion of the retirement burden to the Federal government, Congress passed Section 218 of the Social Security Act in 1951, providing Social Security benefits to public employees in states that entered into a voluntary (but irrevocable) agreement with the Social Security Administration to coordinate state/Federal government benefits.

But the original Social Security retirement benefit formula did not account for workers who had retirement income from both their pension plans through “non-covered” employers (i.e., state or local government employers who did not pay into Social Security), and Social Security benefits through employers who did pay into Social Security. Which was problematic, because Social Security is designed to provide higher replacement rates for lower income workers, but couldn’t distinguish between those who actually had a lifetime of low income, and those who had high lifetime earnings but whose income from “non-covered” state or local government jobs (with its own pension instead) was excluded from the Social Security benefit calculation. Accordingly, policymakers felt that these workers eligible for both Social Security and a non-covered pension benefit were being awarded a higher Social Security replacement rate than they should have been. Thus, in 1983, Congress established the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) to more fairly adjust the Social Security benefit for these “non-covered” workers who appeared, based only on their Social-Security-covered earnings, to be lower-income than they actually had been in their working years.

While the number of workers in the United States who are subject to the WEP is relatively small, it’s becoming more common for advisors to run across clients who are affected by WEP as a greater number of public sector employees who started their careers in non-covered jobs are now approaching retirement.

Fortunately, while the WEP can significantly alter an individual’s total retirement income, there are several strategies that an advisor can employ to minimize that impact, including increasing the number of years with “substantial” earnings from a “covered” employer, or taking a lump-sum distribution of a non-covered pension before becoming eligible for the benefit (thus reducing the length of time the WEP penalty is applied to the Social Security benefit).

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors should be aware of the circumstances under which the Windfall Elimination Provision applies to a retiree’s benefits, and the various rules around how their client’s total retirement benefit (as well as any family/auxiliary Social Security benefits based on the client’s own record) may be impacted by the WEP. At a minimum, it’s crucial to be aware of the WEP to ensure that assumed Social Security benefits are adjusted properly for planning purposes (especially since the WEP adjustment is typically not reflected on the worker’s Social Security statement). And while not all of the WEP penalty can always be unwound even with proactive planning (as might be the case for someone who had a non-covered position early in their career), at the very least, there are a few strategies that advisors have at their disposal to help reduce its overall impact.

According to a report released by the U.S. Government Accountability Office in 2005, 96% of all workers are covered by Social Security benefits. This has not always been the case. When Social Security was first introduced in 1935, the program completely excluded state and local government employees from coverage, because there was doubt as to whether or not the Federal government had the right to tax state and local government workers. Only employees of private companies were allowed to participate.

With the Social Security amendments in the 1950s, state and local employees were given the opportunity to participate in the Social Security system. But this decision wasn’t left up to the individual employees. Instead, each state decided whether it would enter into a voluntary, irrevocable agreement with the Social Security Administration through a “Section 218” agreement, which would offer Social Security and Medicare benefits to state and government workers (and in many cases, allowed states to adjust and potentially reduce their own state pensions to coordinate with the additional Social Security benefits their employees would get instead).

Most states entered into this agreement throughout the 1960s and 1970s, but 15 states chose to stay entirely with their own pension plan and not participate in Social Security. These states believed that they could better provide for their retirees with only their pension plan than a combination of their pension plan and Social Security.

Once Social Security benefits were available to government workers, some policymakers were concerned that government workers were able to retire with their pension and potentially still draw full Social Security benefits for themselves (and their eligible dependents) by working in another job where they paid into the Social Security system, which they felt was unfair and represented a form of ‘double-dipping’ into the system.

Thus, the Social Security Administration introduced two rules that intended to make the system fairer for everyone – the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) in 1983, and the Government Pension Offset (GPO) in 1977 (which was later amended in 1983).

The lack of understanding around these two rules can potentially lead individuals who hold jobs that are not covered by Social Security to make decisions about their retirement based on misinformation and bad advice. As financial planners, the responsibility falls on us to ensure that we can provide recommendations to our clients around these complicated rules.

Because Social Security income can be the backbone of a successful retirement for many clients, advisors need to deeply understand these rules to ensure successful outcomes for clients who are affected by the WEP and GPO.

Individuals who are affected by these rules include those who meet the following criteria:

- Worked at a job where they did not pay Social Security taxes (e.g., some Federal state, and local government employees);

- Qualified for a pension from that job (that did not pay into Social Security); and

- Worked at another job where they did pay Social Security taxes, which qualified them for Social Security benefits.

If an individual meets all three criteria, their Social Security benefits may be subject to both the WEP and GPO Social Security rules. Specifically, the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) reduces a worker’s own Social Security benefit amount from work that they have performed. (At the end of 2018, 1.9 million individuals were affected by the Windfall Elimination Provision.)

The Government Pension Offset (GPO) reduces Social Security benefits to which the individual is entitled based on the work record of another individual such as a spouse, such as spousal or survivor benefits. (At the end of 2018, more than 695,000 people were affected by the Government Pension Offset.)

Since these rules are complex and often confused with each other, this post will focus only on the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP). Financial advisors need to know what the rules around the WEP are, how they work, and why certain strategies should be considered over others.

Why Does The Windfall Elimination Provision Rule Exist?

The Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) was signed into law in 1983 to ensure that benefits were fairly adjusted for individuals who had worked or were working at a job where they did not pay Social Security tax, but still qualified for Social Security.

The formula the Social Security Administration uses for benefits is intended to deliver a portion of pre-retirement earnings, calculated by a “replacement rate” that is generally higher for lower-income earners and progressively lower for those with higher incomes (a form of means-testing where those who earned less receive more of a safety net than those who earned more).

This resulted in what appeared as a ‘windfall’ for those with non-covered earnings because, in the benefit formula, income earned during the years spent working in non-covered employment would be calculated the same as if there were no earnings.

This effectively made an individual with any non-covered earnings appear as if they were a ‘low-income’ worker whose average wages throughout life were less than what they actually did earn. Which meant that their benefit formula employed a high replacement rate factor and, therefore, they received a larger percentage of pre-retirement earnings (from their covered job) than someone with the same amount of total lifetime earnings would normally have received.

In order to compensate for this apparent inequity, the WEP effectively lowers the high replacement rate factor for workers with non-covered earnings, thereby reducing the total Social Security benefit to be received in retirement.

The Basics of the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP)

Before further discussing the details of how the WEP works, it’s important to briefly review how Social Security benefits are calculated. While understanding (or at least estimating) Social Security benefits is usually straightforward for most employees, for anyone who has both covered and non-covered employment on their record, knowing what to expect from Social Security is not so cut and dried.

Calculating Social Security Benefits

Normally, when Social Security benefits are calculated, historical earnings subject to Social Security taxes are indexed to the “average wage level two years prior to the year of first eligibility” (which is age 60, for a person who becomes first eligible at age 62); for years thereafter, annual income is factored into the earnings history at face value. The sum of the highest 35 years of earnings are then divided by 12 months/year x 35 years = 420 months. This gives the inflation-adjusted Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). The AIME is then applied to a formula using replacement rate multiplier factors that calculates the worker’s Primary Insurance Amount (PIA), which is the benefit one would receive at full retirement age.

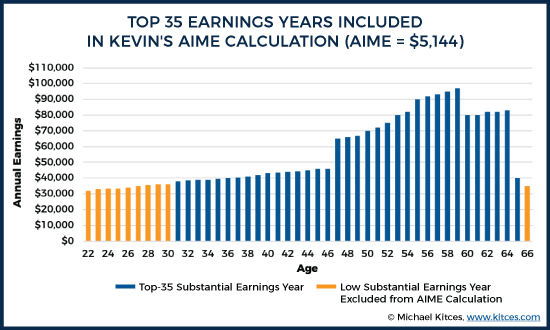

Example 1: Kevin started his career as an athletics program assistant at a private charter high school, but in his late 40s switched careers to a much higher-earning job as a lawyer, with a wind down over a few years at the end of his career before he retired.

Kevin’s average inflation-adjusted earnings over his entire lifetime was $4,637, and after taking the average of the high-35 years, his Social Security Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME) was $5,144.

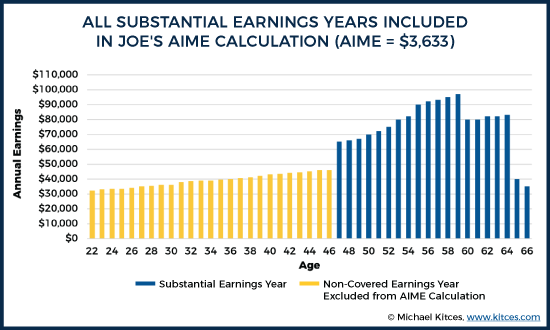

Joe worked a similar career path as Kevin, and had similar lifetime earnings. However, Joe worked as a teacher with a non-covered municipal pension for the first 25 years of his career and then switched to a higher-paying private sector job (that began to pay into Social Security).

While his average lifetime earnings of $4,637 was the same as Kevin’s, given his years of non-covered employment, his AIME was only $3,633.

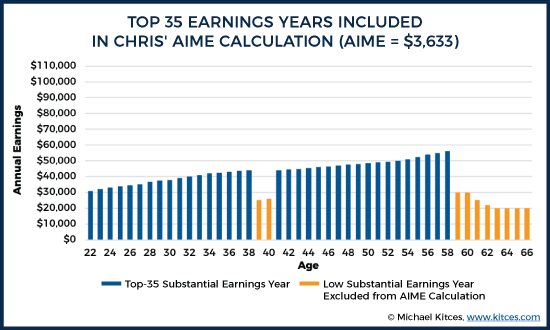

Chris, on the other hand, worked throughout his career in a lower-income job at an electronic parts store, where he started his career as a repair technician and worked his way up to a district manager.

His average lifetime salary was $3,267, and his AIME was $3,633, the same as Joe’s, despite the fact that Chris earned far less in actual income.

Because Joe’s non-covered earnings were excluded in determining his AIME, his 20 years of covered earnings resulted in the same AIME as that for Chris, which were calculated based on Chris’ high-35 years of ongoing work!

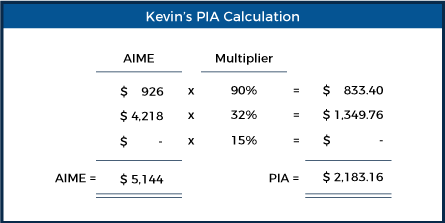

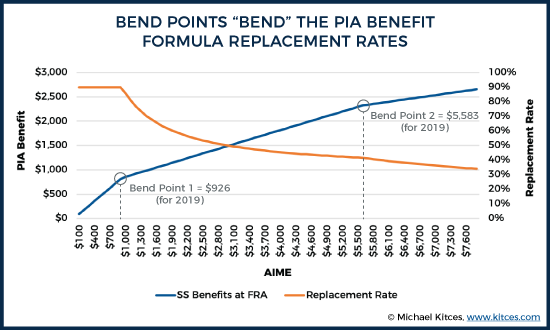

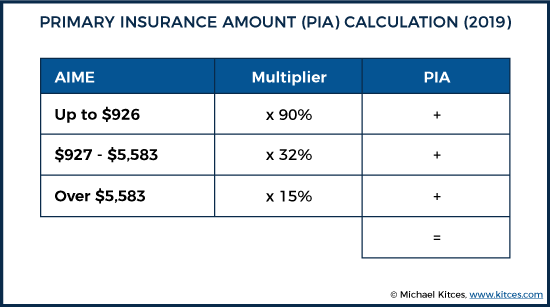

The specific formula to determine the PIA depends on the individual’s year of retirement, and consists of three ranges of AIME levels, separated by two threshold values called “bend points” (because they ‘bend’ the replacement rate).

In effect, these three tiers provide low-income workers with a 90% replacement rate, mid-income workers get a 32% replacement rate, and higher-income earners get a 15% replacement rate.

These bend points are unique to the year of retirement and are adjusted on an annual basis.

For workers retiring in 2019, the ‘normal’ Social Security PIA is calculated from the formula as follows (showing 2019 bend points for monthly AIME amounts of $926 and $5,583):

Example 2: Based on Kevin’s earnings history presented in Example 1, Kevin has an AIME of $5,144. He will retire in 2019 and his PIA is calculated as follows:

Which means that Kevin’s annual retirement income, based on his Social Security benefit calculated with his PIA, would be 12 x $2,183.16 = $26,197.92

How The WEP Adjusts Benefits Based On Years Of Substantial Service

How does the WEP compensate for a worker with non-covered earnings (and who will be receiving pension income in retirement) that reduce a worker’s AIME? By reducing the replacement rate in the benefit formula, which results in a lower PIA. Since the worker with non-covered earnings will also have pension income during retirement from the non-covered job, the WEP essentially reduces the Social Security benefit to factor in the pension income to be received during retirement.

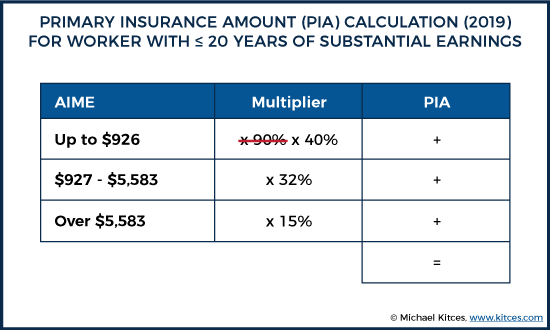

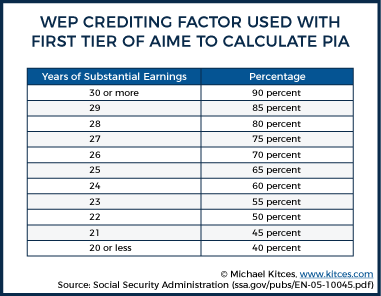

The alternate formula for the Windfall Elimination Provision is identical to this formula with one small difference: the 90% crediting factor, applied to the first tier of AIME, is reduced by a WEP penalty factor that is determined by the number of “years of substantial service”.

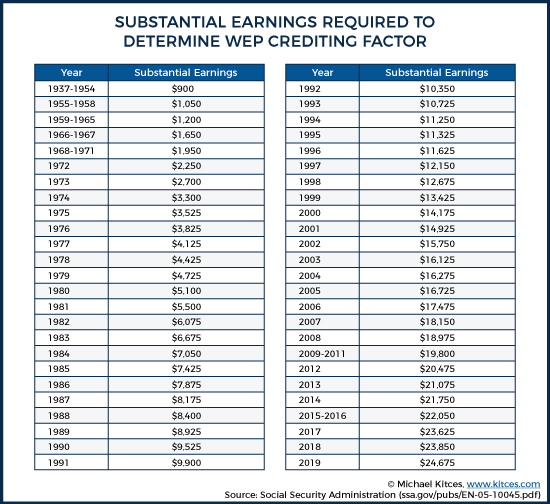

For an individual with 20 years or less of substantial earnings (i.e., the minimum annual income covered by Social Security to earn a year of creditable coverage; for 2019, this is $24,675), the full penalty applies, and the 90% crediting factor is replaced with a 40% multiplier (see Table 1). This means that, for 2019, the maximum WEP reduction that can be made is (90% × $926) – 40% × $926) = $463 per month.

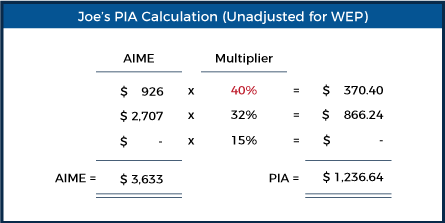

Example 3: Joe (introduced in Example 1) had the exact same average earnings as Kevin, but started his career with 25 years of non-covered employment. He spent only the last 20 years of his career with a covered employer. Thus, Joe’s AIME ($3,633) was much lower than Kevin’s ($5.144).

Since Joe had only 20 years of covered work, the first $926 of his earnings is multiplied by the WEP-adjusted multiplier of 40%, instead of the 90% used when no WEP adjustment is required.

But recall that, in addition to his (WEP-reduced) Social Security benefit, Joe is also entitled to a pension through his non-covered employment.

With an annual pension benefit of $15,000, together with his Social Security benefit of 12 x $1,236.64 = $14,839.68 (calculated with his reduced PIA), Joe’s total annual retirement income would be $15,000 + $14,839.68 = $29,839.68.

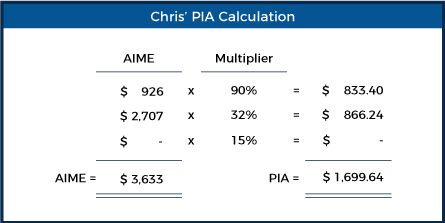

Example 4: Chris (also introduced in Example 1) has an AIME of $3.633, exactly the same as Joe’s. However, Chris’ PIA is higher than Joe’s because the WEP reduction does not apply to him.

Which means that Chris’ annual retirement income, based on his Social Security benefit calculated with his PIA, would be 12 x $1,699.64 = $20,395.68. This is more than Joe’s Social Security benefit, but less than Joe’s total retirement benefit (which includes his non-covered employer’s pension income).

Table 1, below, lists the dollar amount that meets the “substantial earnings” requirement and can be found in the Social Security’s Windfall Elimination Provision publication.

For those who have between 21 and 30 years of substantial earnings, the percentage increases by 5% for every year of substantial earnings. At 30 years of substantial earnings, the crediting factor is back to 90%.

The WEP Guarantee Rule

The one exception to the alternate formula is the “WEP Guarantee” rule, which protects the benefit of a person with some non-covered work, because a near-lifetime of Social Security benefits shouldn’t be materially impaired by just a small amount of non-covered work that didn’t generate much of a pension in the first place. Under this rule, an individual’s Social Security benefit cannot be reduced by more than half the amount of their non-covered pension, regardless of the WEP calculation amounts.

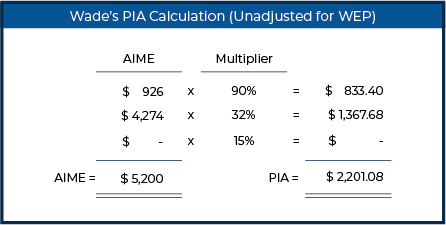

Example 5: Wade is 66 years old and has an AIME of $5,200. He has worked in the private sector for the last twenty years, and thus has 20 years of substantial earnings. Prior to that, he worked for the state, from which he will receive a non-covered pension that will provide him with $600 per month. He will retire in 2019 at his full retirement age.

If Wade’s benefits were not affected by the WEP provision, his PIA would be calculated as follows:

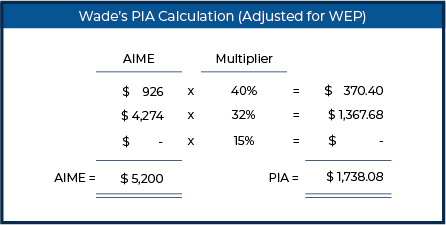

However, because he has only 20 years of substantial earnings, the 90% replacement rate is reduced to 40%. Thus, ignoring his pension, Wade’s PIA would be calculated as follows:

Which results in a reduction of $2,201.08 - $1,738.08 = $463. But, given the WEP Guarantee rule, his benefit cannot be reduced by more than half his pension benefit, which is $600 ÷ 2 = $300. Therefore, his reduction would be limited to $300, and his total PIA would be calculated as follows:

$2,201.08 – $300 = $1,901.08.

Note: Individuals affected by the WEP will often have much lower benefits in the first place, as not many earn $110k for 20 years (such as Wade, the client in our example) when the median household income is only around $60k.

How WEP Is(n’t) Shown on Your Social Security Benefits Statement

It is important to note that Social Security Benefit Estimate statements always calculate monthly benefits using the full 90% replacement rate for the first tier (not the reduced rate, which can be as low as 40%), because they are not aware of which years (if any) include non-covered earnings.

The Social Security benefits estimate statement says this:

In the future, if you receive a pension from employment in which you do not pay Social Security taxes, such as some federal, state or local government work, some nonprofit organizations or foreign employment, and you also qualify for your own Social Security retirement or disability benefit, your Social Security benefit may be reduced, but not eliminated, by WEP. The amount of the reduction, if any, depends on your earnings and number of years in jobs in which you paid Social Security taxes, and the year you are age 62 or become disabled.

Any reduction in benefits due to a non-covered pension will not be reflected in the benefits estimate section of the individual’s Social Security statement, because the Social Security Administration does not know whether an individual is eligible for a pension from non-covered work and will thus use the normal benefit formula to calculate future payment estimates.

The Social Security Administration only learns about non-covered employment once the individual applies for benefits and will then recalculate the benefit with the alternate WEP formula. However, the years of substantial service do not have to be met when filing for benefits. If, at any time, a worker accumulates enough years, they can request that their benefit be recalculated to reflect the lower penalty.

While it is possible to calculate a retiree’s benefit after the WEP reduction by hand, there are easier ways to estimate what that benefit will be (without having to visit or call to the Social Security Administration). The WEP Calculator is one of the best-kept secrets on the Social Security website and can be found on their calculators page (along with other useful calculator tools). By providing birthdate, expected retirement age, any non-covered pension benefit amounts, and historical (and projected future) earnings, the calculator will estimate the new benefit amount factoring in the WEP rule.

The WEP Effect on Filing Early or Late

But what happens if a client wants to (or should) file for benefits early? The benefit amount is reduced due to retiring before normal retirement age, but how exactly is the WEP penalty affected? Alternatively, what if a client waits until beyond their full retirement age to file and earns delayed retirement credits; will their penalty amount increase, too?

The WEP reduces the benefit amount before it is adjusted for early or delayed retirement credits. It is this WEP-reduced benefit that becomes the new WEP-adjusted PIA, and that PIA is then adjusted according to filing age.

Example 6: Sue’s full retirement age is 66, and she has a monthly Social Security benefit of $1,463. She has 20 years of substantial earnings, so the maximum WEP penalty (for 2019) of $463 is applied to Sue, reducing her PIA to $1,463 – $463 = $1,000.

If Sue files for her benefits at age 66, her benefit is $1,000 after the reduction for WEP. In this case, the WEP penalty amount is exactly $463.

What would be the penalty amount be if Sue files for benefits early? Remember, her benefit will be reduced for the WEP first, and then reduced based on her filing age.

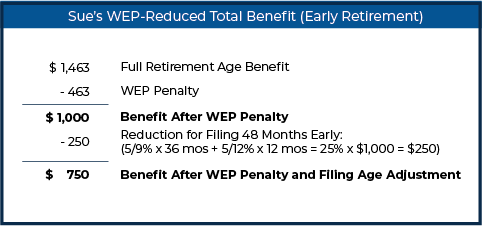

Example 7: Sue, from our last example, decides to retire early, at age 62. Her total benefit, reduced first by the WEP rule, and then adjusted for her early retirement, is calculated as follows:

If Sue were not subject to the WEP and still filed at 62, her benefit would be $1,463 – ($1,463 x 25%) = $1,097.25. However, since she is subject to the penalty, her total benefit is $750.

This means the effective penalty is $1,097.25 – $750 = $347.25. Or viewed another way, the good news, at least, is that if Sue retires early and her benefit is reduced accordingly, so too is the magnitude of the WEP reduction.

And how would Sue’s benefit be affected if she decided to retire later?

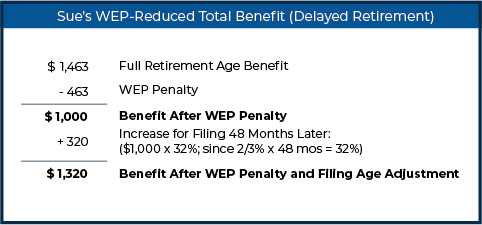

Example 8: Instead of retiring early, Sue, from our last two examples, has changed her mind and has decided to retire later, at age 70. Her total benefit, reduced by the WEP rule and adjusted for her delayed retirement, is calculated as follows:

If Sue were not subject to the WEP, and filed for benefits at 70, her benefit would be $1,463 + ($1,463 x 32%) = $1,931. However, since she is subject to the penalty her total benefit is $1,320.

This means the effective penalty is $1,931 – $1,320 = $611.16. Which means that in the case of delaying, the impact of the WEP is to reduce the value of delayed retirement credits.

The effect of decreasing the full retirement age benefit with the WEP penalty before age-based increases or reductions are applied means that slightly different calculations must be used when assisting clients in figuring out their benefits at various ages.

The Effect of the WEP to Family And Auxiliary Benefits

Social Security benefits aren’t just for the retiree as an individual. They can also be paid to eligible spouses and children of the retiree. However, the benefit upon which those payments are based will also be reduced under the WEP.

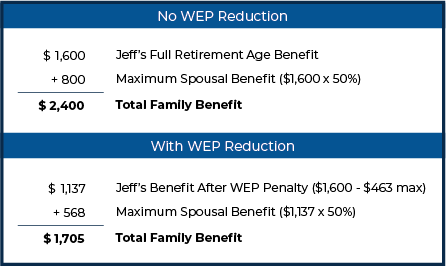

Example 9: Jeff’s benefit before the WEP reduction is $1,600 (at full retirement age). After applying the rules under WEP, Jeff’s new benefit after the maximum $463/month reduction (assuming he had no more than 20 years of substantial earnings) would be $1,137. It’s this amount reduced by the WEP penalty that will be used to calculate benefits payable to his eligible spouse.

Without the WEP, Jeff’s total family benefit is $2,400. With the WEP the total family benefit is $1,705.

The WEP penalty results in a total reduction of a whopping $2,400 – $1,705 = $695, because it not only reduced Jeff’s individual benefit, but also the benefit base on which the 50% spousal benefit is calculated as well!

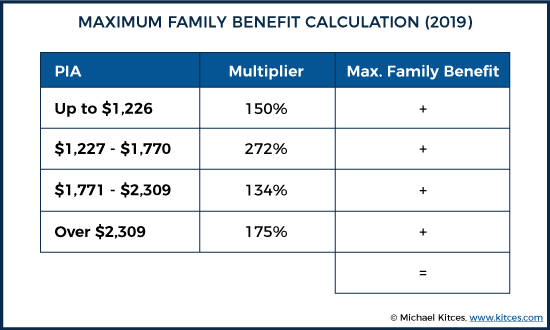

It’s important to note that the WEP-reduced PIA is used in the calculation for the family benefit maximum amount. This calculation determines the cumulative maximum amount that can be paid to all of an individual’s family members (including the individual themself), based on that individual’s work record, ranging from 150% to 188% of their full retirement age benefit if they retire (or die).

The method used to compute the family maximum is similar to that used for the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA), discussed earlier. Like the PIA calculation, the family benefit calculation uses “bend points”, consisting of annually-adjusted dollar amounts determined by the year an individual attains age 62 (or dies). And also like the PIA calculation, the maximum family benefit are also adjusted for starting early or late. But while the PIA calculation is based on the individual’s AIME, the family maximum benefit is based on the individual’s WEP-adjusted PIA.

Below is the formula to calculate the maximum family benefit for an individual who turns 62 in 2020:

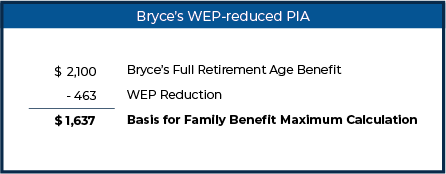

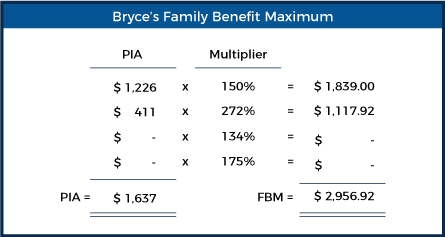

Example 10: Bryce’s monthly benefit before the WEP reduction is $2,100 (at full retirement age). Bryce has a spouse who is also full retirement age, and two children ages 9 and 12. After applying the rules under WEP, Jeff’s full retirement age benefit after the maximum WEP penalty reduction of $463/month (assuming he had no more than 20 years of substantial earnings) would be $1,637/month.

This is Bryce’s WEP-reduced PIA, which will be used to calculate the maximum benefit payable to his eligible family members.

Applying this amount to the family maximum calculation, the total family benefit is calculated as follows:

This means that Bryce’s family’s maximum benefit would be $2,956.90/month (rounded to the nearest $0.10), 180% of Bryce’s full retirement age benefit.

So on top of Bryce’s own 100% benefit ($1,637/month), his spouse can receive an additional 50% of benefits ($818.50/month, as the spousal benefit is limited to 50% of of Bryce’s full retirement amount), and the remaining share will be designated for Bryce’s children.

It is important to note that if an individual were to die, their Social Security benefit would be recalculated with the normal formula, and the WEP penalty would no longer apply. The WEP-adjusted PIA is used for normal retirement benefits (adjusted earlier or later as appropriate) and for the family maximum benefit based on that worker’s PIA, but not survivor benefits after the individual passes away.

Planning Strategies To Manage the Windfall Elimination Provision

There are two official ways to navigate the WEP that can potentially result in a more favorable outcome, which are important for advisors to understand to help clients who can take advantage of these strategies.

Continuing To Work Can Reduce The WEP Penalty

The first opportunity to mitigate the WEP penalty is to accumulate additional years of substantial earnings. The WEP penalty starts to lessen at 21 years of substantial earnings and goes away completely at 30 years (see Table 1, earlier). This phase-out of the WEP reduction offers an incredible planning opportunity if an individual has worked at a job where they paid Social Security tax.

For example, if a client worked as an engineer for 20 years in a job covered by Social Security before they began teaching at a public school (that wasn’t covered by Social Security), the client may be able to do enough part-time work between now and when they retire to add another 10 years of substantial earnings, completely eliminating the monthly WEP reduction by topping up to the 30-year substantial earnings threshold.

Or, if the client’s spouse is self-employed, it could make sense to add the client onto the spouse’s payroll, to accumulate the required years of substantial earnings. (Which may also be helpful in increasing the individual’s own Social Security benefit itself, in addition to reducing its exposure to the WEP.)

Would it be worth it? If you consider how much more your client could receive in benefits over the lifetime of retirement, it could be worth more than $100,000 in extra income over a 20-year retirement (for an individual whose benefit is reduced by the maximum $463 monthly penalty, without adjusting for inflation).

Obviously, not everyone has the option of accumulating enough years to eliminate the potentially substantial monthly WEP reduction. Someone who is nowhere near the 20-year threshold where WEP at least begins to phase out, accumulating additional years of substantial earnings may not be helpful. But this option may be worth taking a closer look for someone in the WEP zone, having accumulated 20 to 30 years of substantial earnings, as even just one year of additional work can materially reduce the WEP impact.

If you want to use this phaseout, check your client’s earnings history and mark the years that meet the definition of “substantial” (see Table 2), which will identify the number of years needed to reach the number of years to eliminate the WEP penalty (or at least how much the penalty will be reduced based on the number of additional years the client is able or willing to work). And don’t hesitate to question the accuracy of an earnings record; mistakes here are not uncommon. For someone trying to meet the definition of “substantial” earnings, it’s well worth verifying the information is correct.

The Lump-sum Pension Withdrawal

Often, individuals will wonder if they can mitigate or even avoid the WEP rule altogether by simply taking their pension in a lump sum. After all, in just about every reference to these rules, the Social Security Administration says that the rules apply to individuals with a pension from work where no Social Security taxes were paid. So can someone ‘avoid’ having a pension from a non-covered job by not taking the pension in the first place and choosing a lump sum instead?

Possibly, but not often. For certain individuals, taking out a pension as a lump sum can sometimes be a valid method to mitigate some of the penalty, but not to avoid it altogether.

In most cases, taking a withdrawal from a non-covered pension causes the Social Security Administration to use an alternate calculation to determine the amount a worker would have received based on their age and the date they took the lump sum. It doesn’t matter that the funds were taken as a lump sum; to the Social Security Administration, it still looks like a normal pension.

The Social Security website has this to say about the issue:

When the entire pension is paid in a lump sum, the amount may represent a payment for a specific period of time or a “lifetime.” Generally, the pension-paying agency will prorate the lump sum to determine a monthly amount for WEP purposes.

If the agency will not provide this information, prorate the lump sum to determine the monthly pension amount as follows:a. Specific Period – divide the lump sum by the number of months in the period specified by the pension-paying agency. See RS 00605.360C.5.a. for when WEP application ends.

b. Lifetime or Unspecified Period – divide the pension lump-sum amount by the appropriate actuarial value in the table that corresponds to the worker’s age on the date of the lump-sum award.

This language does two things: it provides the Social Security technician with directions on how to treat a lump-sum pension, and it also directs the Social Security Administration as to when the WEP should no longer affect a benefit payment. If an individual receives a payment for a certain period in lieu of a pension, the end of that period is when the WEP application will end.

On rare occasions, an employer may permit “unique payment” schedules for pension benefits. For example, a client might be allowed the option to take a lump-sum payment in lieu of a 10-year payment period; in this situation, the WEP would no longer affect them after 10 years. However, it is more common that no special distribution period is specified. In these situations, when a lump-sum distribution is taken, the Social Security technician will use a table on their website to determine how long the payments should have lasted. At the end of that period, the WEP would no longer be applied.

So while a lump-sum distribution may curtail the WEP penalty by reducing the length of time to which the penalty is applied to the Social Security benefit (generally, from when Social Security begins until their Social-Security-table-estimated life expectancy), it does not help a client avoid the penalty completely.

However, the implicit conversion of a pension lump sum back to a pension only applies if someone was eligible for the pension in the first place. If the value of the pension is withdrawn as a lump sum before it was eligible to be taken as a pension, then it really would make the WEP reduction disappear.

Example 11: Stacey is a teacher who works in Texas. She contributes 7.7% of her pay to her school pension fund. Additionally, the state of Texas contributes 7.5%, and Stacey’s school district contributes 1.5%.

After working as a teacher for five years, Stacey decides to switch careers and leaves the school district before she ever becomes eligible to receive pension benefits. She requests a refund of her pension contributions, and receives everything she has contributed, along with the interest her contributions have accrued.

Since she does not receive any of the state or school district contributions (and because the refund of her contribution is actually processed before she would have become eligible for the pension), she is not subject to the WEP penalty.

Here’s what the Social Security website says in section RS 00605.364 of their Program Operations Manual System, “Determining Pension Applicability, Eligibility Date, and Monthly Amount”:

Withdrawals of the employee’s own contributions and interest made before the employee is eligible to receive a pension are not pensions for WEP purposes if the employee forfeits all rights to the pension. This rule applies even if the employer paid the employee contributions.

Withdrawals of the employee’s own contributions and interest made after the employee is eligible to receive a pension are considered a lump-sum pension for WEP purposes.

Any separation payment, withdrawal, or refund consisting of both employer and employee contributions is a pension; for WEP purposes whether made before or after the employee is eligible to receive a pension.

It’s crucial to understand the meaning of the word eligibility as defined by the Social Security Administration – it does not mean that someone has simply stopped working! In fact, a person could still be working and deemed “eligible” for their pension. This would be disastrous to those individuals who planned to wait until a week before they retired to withdraw their contributions. The Social Security Administration defines “eligibility” as follows:

An individual becomes eligible for a monthly pension or a lump sum in lieu of a monthly pension the first month he or she meets all requirements for payment except stopping work and applying for the payment. [emphasis added]

In other words, a client could still work and technically be eligible to access their pension. However, in all but a few isolated cases, having a client completely withdraw their own contributions from their pension plan to escape the WEP penalty just doesn’t make sense. The client would have to leave all of their employer contributions behind and forgo their rights to the pension checks. Sure, they’ll get penalty-free Social Security benefits – but the amount of additional benefits is usually much smaller than the pension they left behind.

If an individual still chooses to withdraw their pension contributions to avoid the WEP, they should know exactly what it takes for them to become “eligible” for the pension with their employer before attempting to do so (and to ensure they actually make the withdrawal itself before becoming eligible for the pension).

Example 12: Jonas is a client who has been working at his job in Texas since he was 50 years old. He will become eligible for his pension at age 55 if he has 5 or more years of service credit.

If Jonas stops working at 56 (when he would have accrued six years of service credit) and waits until then to withdraw his pension, it will be too late to avoid the WEP penalty.

However, if Jonas leaves his job at age 54, and requests a refund of his contributions (which would include any interest from those contributions), he would avoid the WEP penalty, since he withdrew his contributions before he reached age 55 (at which point he would have become eligible for his pension).

What Happens If a Client Has Mixed Earnings or Mixed Employment?

In many states, there are school districts that do not participate in Social Security. Instead, they have their own pension plan to which they contribute. Some school districts in these states, however, have adopted agreements with the Social Security Administration that allow them to participate in both Social Security and their own pension plans.

For example, the school districts in my hometown of Texarkana, TX do not participate in Social Security. They only contribute to the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) of Texas. However, scattered around my state are several school districts, such as Austin Independent School District (ISD), that participate in Social Security in addition to Texas TRS.

If an educator spends their entire career at a district that contributes solely to Social Security, WEP will not impact their benefit. Alternatively, if they spend their entire career at a district that contributes solely to TRS, there won’t be any Social Security benefit at retirement to begin with. And if they have earnings covered by Social Security from some jobs and earnings that paid into TRS from other jobs, there isn’t usually an issue in calculating what their benefits may be as benefits can be determined by the number of years of substantial earnings. However, if an educator works at a school district that contributes to both Social Security and a state pension plan, these ‘mixed earnings’ can make it more challenging to properly calculate how much to expect in Social Security benefits. Similarly, benefit calculations can also be challenging for an educator with ‘mixed employment’ (i.e., if they receive ‘mixed earnings’ from one school district and earnings from other jobs that were either covered or not covered by Social Security).

Advisors should understand how the benefits for clients with mixed earnings will be impacted by WEP; without a clear understanding of this, a clients’ Social Security benefit may be incorrectly reduced.

Calculating WEP with Mixed Earnings – A Case Study

As an example, we’ll look at Denise, who worked at Austin ISD for 15 years where she paid into both Social Security and TRS. When her husband died, she moved to Texarkana and started working for Texarkana ISD, where she spent the last 15 years of her teaching career. While in Texarkana, she paid into TRS only, with no payments into Social Security.

She retired with a TRS pension that provided $1,500 per month and was also eligible for Social Security benefits. She had always heard about the Social Security provisions that would reduce an educator’s benefit amount, but she wasn’t sure how much she would receive from those benefits once they were reduced.

Denise was confused by the research she did because everything she found referenced the fact that the WEP applied only to individuals with a pension where no Social Security taxes were paid. Only half of her pension came from work that did not pay into Social Security, but the other half was from her time in Austin where she did pay Social Security taxes.

After speaking with a Social Security Administration claims representative, Denise was under the impression that the work where she paid Social Security taxes didn’t matter. Unfortunately, this was not correct and Denise’s misunderstanding could have cost her several hundred dollars per year in missed benefits.

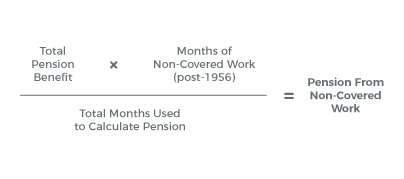

The WEP still applies for those with mixed earnings, and Social Security benefits can only be reduced by a maximum of half of a non-covered pension. When part of the pension comes from covered work, the non-covered pension is calculated by the pro-rata share of time spent at the non-covered school district.

If your client has work from both covered and non-covered earnings within the same retirement plan, you need to know how to prorate the pension.

Prorating Pensions With Mixed Earnings

The Social Security Administration implies it is simple to verify the amount of a prorated pension, indicating that a person should “request verification from the employer or pension-paying agency showing the amount of the pension based on only the government employment.”

However, clients may run into issues obtaining this information from pension-paying agencies, because many of them just don’t keep these types of records. If that’s the case, the advisor can ask the client for employment records and their Social Security earnings history, and then use the following formula to determine the client’s prorated non-covered pension:

Months that include both covered and non-covered employment are considered a covered work month.

Since Denise worked for 15 years at a covered school district and 15 years at a non-covered school district, 50% of her pension would be considered non-covered, attributable to the 15 years she spent while receiving non-covered earnings, out of the total 30 years she worked for the employers providing the pension benefit.

Thus, since Denise’s total pension benefit was $1,500 per month, the true “non-covered” pension amount would be $1,500 x 50% = $750 per month. In this case, the most the WEP penalty could be is half of that amount, or $375.

Ultimately, the key point here is that a clear understanding of how the WEP penalty and pension guarantee rules work can save clients from losing out on Social Security benefits, which is especially relevant when clients have income consisting of ‘mixed earnings’ from covered and non-covered jobs.

How 401(k) and 403(b) Plans, 457 Accounts, and ORPs Factor into the WEP Rule

Many government employers offer supplemental retirement plans in addition to their pension plan. Does a distribution from these plans trigger the WEP? Whether the amount a client saved in these plans could trigger the WEP depends on individual employers. Here’s what the Social Security Administration handbook says:

Payments received from defined contribution plans (e.g. 401(k), 403(b), or 457 plans) based on non-covered employment are considered a pension subject to WEP regardless of the source of contributions (employer only, employee only, or a combination of both), if the plan is the primary retirement plan. If the plan is a supplemental plan, the payments are subject to WEP when the plan payments contain employer or both employer and employee contributions.

Essentially, if the 403(b) or 457 is a supplemental plan, in addition to the employee’s actual (non-covered) pension, and only contains the client’s contributions, it will not be subject to the WEP calculations. However, if it is the primary plan or a supplemental plan with employer contributions, it will trigger the WEP calculation. This means that a lump-sum amount taken from the plan will be calculated as if the client took it in a series of payments like a pension, similar to how a lump sum taken from a pension plan itself is still treated as a pension as well.

ORP Participants Are Not Necessarily Subject to the WEP Rule

An article on the complexities of Social Security for those with non-covered pension plans (most commonly, educators for various state and local municipalities) wouldn’t be complete without a mention of those who work in higher education – specifically, those employees of community colleges and universities who are given the choice between a Teacher’s Retirement System and an Optional Retirement Plan (ORP), both of which may be subject to WEP.

While Optional Retirement Plans vary on a state-by-state basis, they essentially allow certain higher education employees to opt out of the Teachers Retirement System in favor of a retirement plan that allows them to make their own contributions and receive a match from their employer. The dollars in the plan can be invested in a variety of ways.

There are rules on the Social Security Administration website (which pertain to the Texas ORP, but in my experience, are very similar across other states) explaining how the ORP triggers the WEP, and are summarized as follows:

- The trigger for the WEP reduction does not occur until you become entitled to benefits from your ORP.

- Entitlement does not occur until you take a distribution.

- For purposes of the WEP trigger, a distribution is a rollover of any type, a lump-sum distribution, or periodic payments.

- Distributions are required no later than April 1 of the year following the year you attain age 70 ½.

As long as a worker does not activate a WEP trigger, they are not entitled to their ORP and thus are not subject to the WEP.

Workers with ORPs who are also eligible for Social Security are usually not aware of these triggers and often assume that their Social Security benefits will immediately be subject to reduction by the WEP. This is simply not true. An individual can delay the WEP reduction of their Social Security benefits until age 70 ½ if they delay ORP distributions (which will then result in a “triggering event”).

This could mean several years of Social Security benefits with no reduction. Depending on when a worker’s birthday falls, there’s an average of 113 months between age 62 and April 1st of the year after an individual attains age 70 ½. So if an individual were to file for Social Security benefits at age 62, they would potentially avoid the WEP deduction for as long as they don’t become “entitled” to their ORP. And with the current WEP penalty of $463 that could mean more than $50,000 in Social Security benefits from age 62 to 70 ½ ($463 per month x 113 months)! This estimate does not include annual cost of living adjustments, which would only increase the total benefit.

However, filing early to claim more year of Social Security benefits without a WEP penalty, at least until a triggering event occurs, may not make sense for all clients with ORPs. While it may be a valuable strategy for some (e.g., individuals with shortened life expectancies, or who have auxiliaries whose benefits cannot begin until the worker files for benefits), the reduction in lifetime Social Security benefits for early filing must also be taken into account. In other words, it may be more valuable for many workers to delay Social Security all the way to age 70 to receive higher benefits (with delayed retirement credits) for decades to follow (albeit reduced by the WEP), rather than try to squeeze in 8 years of non-WEP-reduced benefits but lose a potentially 132% increase in benefits (for waiting from age 62 to 70) for all the decades thereafter.

And for many workers, delaying ORP benefits may not even be an option in the first place, as retirees may need the income from their accounts much earlier. However, some strategic retirement income planning may allow clients to pull income from other sources and eliminate (or at least reduce) the need for touching those ORP dollars until they’re required to take a distribution. ORP accounts can also stay where they are when a client retires, as rollovers are a triggering event for the WEP rule.

The WEP was established to adjust Social Security income for workers receiving pension benefits from employers who did not contribute into Social Security, and is based on an individual’s non-covered income, preventing these employees from receiving high replacement rates for appearing as ‘low income’ earners when in reality, they may have been high-income earners who simply had a number of years in non-covered jobs. Increasing the years of substantial earnings has the effect of unwinding the WEP penalty, such that when a worker has accumulated at least 30 years of substantial earnings, the WEP will no longer be applicable.

Fortunately, there are strategies for advisors to help their clients mitigate the impact of the WEP. An individual with non-covered earnings can potentially avoid the WEP altogether by accumulating enough years of ‘covered’ employment.

Partial or full lump-sum distributions can also reduce how long the WEP penalty will affect their benefit; if it makes sense to withdraw an employee’s contributions into the pension (along with the interest) before they become eligible to receive benefits, that could also serve to avoid any WEP penalty.

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors should be aware of how the WEP rule can impact their clients’ retirement benefits, and understand the potential strategies on how to minimize the impact for clients who may be affected by the provision. And while the WEP only addresses one aspect of the individual’s Social Security benefit – that is, the benefit the workers themselves are entitled to – there are other factors (e.g., the Government Pension Offset) that need to be considered when helping clients maximize their retirement benefit.