Executive Summary

The decision of when to begin taking Social Security benefits is one of the most important questions for many retirees. Unfortunately, thanks to the maze of Social Security rules individuals must navigate, it is often also one of the most complex. And while many retirees are aware that claiming Social Security benefits “early” can lead to a reduced benefit, research has shown that fewer individuals understand the Earnings Test rules that can also impact benefits when a young (pre-Full-Retirement Age) worker decides to claim benefits while also still working.

Under the Earnings Test rules, if an individual is under their Full Retirement Age for all of 2019, then Social Security will withhold $1 of benefits for every $2 of earnings over the annual $17,640 limit. Similarly, if an individual reaches their Full Retirement Age in 2019, then the annual Earnings Limit threshold is increased to $46,920, and Social Security will withhold “only” $1 of benefits for every $3 of earnings over that amount. And notably, only earnings attributable to work performed before an individual reaches their Full Retirement Age counts toward that total.

When benefits are withheld due to the Earnings Test, the Social Security Administration will withhold such benefits starting at the beginning of each year (or immediately when benefits begin midyear) and continue to not pay benefits every month until the full amount has been withheld. Furthermore, Social Security does not pay partial benefits for any month, so for those impacted by the Earnings Test, no benefits are paid until a full month’s Social Security check can be paid.

Individuals who retire midyear often benefit from special “Grace Year” rules, which apply in the first year in which an individual is entitled to a Social Security benefit and earns less than the “monthly limit” in at least one month. Under these rules, an individual is entitled to receive an unreduced-by-the-Earnings-Test benefit for any month in which they did not earn more than the monthly limit. The monthly limit is 1/12 the annual limit.

Notably though, while the Earnings Limit can reduce (or even eliminate entirely) a pre-Full-Retirement-Age worker’s monthly benefit, no similar restrictions apply to other types of income. Thus, a young Social Security recipient can have substantial retirement distributions, portfolio income, and/or other non-earned-income without having any benefits withheld due to the Earnings Test.

It’s also important to note that the Earnings Test impacts different types of Social Security benefits differently. An individual’s retirement benefit or survivor’s benefit, for instance, is only impacted by the Earnings Test based on that individual’s own earnings. By contrast, spousal benefits can be “hit” with the Earnings Test if either the spouse receiving the benefit is young and working, or if the spouse on whose earnings record the benefit is being paid is young and working!

Thankfully though, benefits “lost” to the Earnings Test aren’t generally lost forever. Instead, when an individual reaches Full Retirement Age, the Social Security Administration will recalculate the individual’s Earnings-Test-reduced-benefit, reducing the actuarial reduction for claiming early by the number of months in which no benefits were received due to the Earnings Test.

There are, however, some situations in which benefits withheld by the Earnings Test truly are lost forever. Such scenarios include situations in which a Social Security recipient does not live long enough to reap the benefits of an actuarial reduction, and those where an individual who is already past their Full Retirement Age is eligible for spousal benefits, but has spousal benefits withheld due to a younger working spouse’s earnings.

The Social Security rules are extraordinarily complex and create a virtual labyrinth that retirees must successfully navigate to get the most out of the system they have likely been paying into for most of their lives. In particular, the timing of when benefits are claimed can have a significant impact, not only because benefits are adjusted (i.e., reduced) for those who retire “early,” but also because of the so-called Social Security Earnings Test applies to anyone who receives Social Security benefits early.

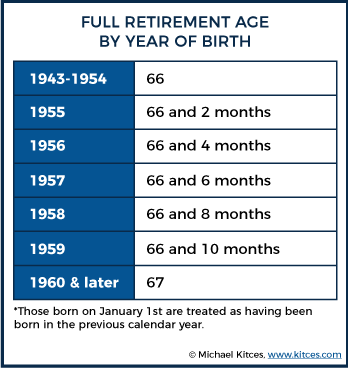

Unfortunately, the complexities that arise when retiring early start with just defining what constitutes “early” in the first place. When it comes to Social Security benefits, claiming early can be defined as “claiming prior to one’s ‘Full Retirement Age’ (FRA)”, which itself may be age 66, age 67, or some number of months in between, depending on the individual’s Birth Year in the first place.

Unfortunately, the complexities that arise when retiring early start with just defining what constitutes “early” in the first place. When it comes to Social Security benefits, claiming early can be defined as “claiming prior to one’s ‘Full Retirement Age’ (FRA)”, which itself may be age 66, age 67, or some number of months in between, depending on the individual’s Birth Year in the first place.

Notwithstanding the variability of exactly what constitutes “early” for early retirement, though, the essence of the Earnings Test is very simple: when individuals who start their Social Security benefits early end out earning “too much” their Social Security benefits are reduced (potentially all the way to $0!).

Social Security Earnings Test For Years Prior To Full-Retirement-Age Year

When calculating the impact of the Social Security Earnings Limit for those who claim Social Security benefits before Full Retirement Age, it is important to distinguish between the calendar year in which an individual attains Full Retirement Age, and years prior to reaching that landmark age. This is due to the fact that the Earnings Limit test uses both a different limit and a different formula in the year a person reaches Full Retirement Age, as compared to earlier years.

If an individual is below Full Retirement Age for the entire year (e.g., they are still just 62, 63, 64, or 65 this year), the earnings limit begins to impact benefits once earnings exceed $17,640 (in 2019). After total earnings exceed this threshold amount, the Social Security Administration will withhold (i.e., reduce) $1 of benefits for every $2 of earnings above that limit. Notably, though, the $1 of benefits withheld (for every $2 of earnings over the limit) applies to a Social Security recipient’s total annual benefit, and not the monthly benefit.

Example #1: Charles is 64-year’s old and begun receiving his Social Security Retirement benefit in 2018. For 2019, Charles anticipates receiving $1,000 of benefits per month, or $12,000 in total annual benefits.

Charles, however, decides to continue working part-time, and throughout the course of 2019, he earns $22,140 in 2019. As a result, the total amount of Social Security benefits Charles receives in 2019 will be reduced due to the Earnings Limit.

Since Charles’s earned income is $22,140 - $17,640 = $4,500 more than the 2019 threshold amount, he will have $4,500 / 2 = $2,250 of his 2019 annual benefits withheld by the Social Security Administration. Thus, instead of the $12,000 of total annual benefits to which he would otherwise be entitled, Charles will receive $9,750 of Social Security benefits in 2019 (though technically, due to the way Social Security withholds benefits under the Earnings Test, as explained in greater detail below, Charles would actually receive only $9,000 of Social Security benefits in 2019, and would then receive an additional $750 in early 2020 for 2019).

Intra-Year Timing Of When The Earnings Test Reduces Social Security Benefits

Given the importance of cash flow in planning, It’s also important to understand just how the Social Security Administration withholds benefits pursuant to the earnings test. The natural inclination of many is to think that benefits are withheld proportionately from each Social Security check throughout the year. But that is, in fact, not the way the benefit reductions are applied.

Instead, the Social Security Administration asks individuals to estimate their income for the year and then bases the amount of benefits withheld on those estimates. Notably, to avoid under-withholding benefits that would eventually have to be repaid, potentially causing undue financial and cashflow hardships, Social Security Administration employees are supposed to encourage individuals to use conservative (i.e., high) earnings estimates unless they are reasonably certain of exactly what earnings will be. Then, armed with an individual’s own earnings estimates (which can be updated by contacting the Social Security Administration), the Social Security Administration will withhold all applicable benefits for the year before any benefits are paid.

Specifically, Program Operations Manual System (POMS) Section Chapter RS – Retirement and Survivors Insurance, Section 02501.095(B)(1) states “Charge an individual’s excess earnings to each monthly benefit beginning with the first month the individual is entitled in the year in question and continuing until the excess is recovered or until all the benefits have been withheld for the year. Do not charge the excess for one year into the next year.”

Thus, benefits are withheld starting at the beginning of each year (or immediately in the case of an individual applying for benefits during the year), and no Social Security benefits are paid until enough benefits have been withheld to allow a full month’s Social Security check to be paid. Then, after the year has ended, the Social Security Administration will calculate the exact amount of benefits that should have been reduced, and will either pay any prior underpayment (if over-withholding occurred), or let a beneficiary know that they were “overpaid” (and require that the recipient repay their "excess" Social Security benefits).

Example #2: Recall Charles, from example #1, who had anticipated receiving $12,000 of Social Security benefits in 2019, but due to the earnings test, will only be entitled to $9,750 of benefits.

While Charles’ average monthly Social Security benefit for 2019 will be $9,750 / 12 = $812.50, he will not receive monthly checks of that amount. Instead, Charles will not receive any Social Security benefits for 2019 until he can receive his “full” $1,000 monthly benefit amount. Thus, he will receive no benefits in January, February and March.

Beginning in April, he will receive his full $1,000 per month benefit, which will continue to be paid monthly throughout the remainder of the year. In early 2020, the Social Security Administration would review Charles’s 2019 earnings, and would pay him the $750 partial month benefit he is owed for March of 2019.

Earnings Test For The Full-Retirement-Age Year

In the calendar year that a Social Security recipient reaches their Full Retirement Age, the Earnings Test uses a separate threshold amount and formula to determine how much, if any, of an individual’s benefits should be withheld.

Specifically, a person reaching Full Retirement Age at any time during the current year may earn up to a much-higher $46,920 (in 2019) before any Social Security benefits are withheld. Once earnings exceed that threshold, Social Security will withhold $1 of benefits for every $3 of earnings over the limit (instead of the $1-for-every-$2-over formula that applies to prior years).

Example 3a: Frankie is the Office Manager of a large law firm and has a $102,000 salary, paid in monthly installments of $8,500. She was born on July 2, 1953, and thus, will reach her birth-year-specific Full Retirement Age of 66 in July 2019. Frankie, however, decides to begin collecting Social Security retirement benefits in January 2019, which, prior to any impact of the Earnings Test, have been calculated to be $2,000 per month.

Frankie will earn a total 6 x $8,500 = $51,000 prior to the month in which she reaches her Full Retirement Age (which is more than the $46,920 threshold amount for 2019), and therefore her pre-Full-Retirement-Age Social Security benefits will be reduced.

Specifically, Frankie’s $51,000 of countable earnings are $4,080 more than her $46,920 threshold amount. Thus, under the $1-for-every-$3-over formula that applies to benefits received in the year an individual reaches their Full Retirement Age, Frankie will have $1,360 of her benefits withheld by the Social Security Administration. Thus, Frankie will have her $2,000 January 2019 check withheld by Social Security (since partial payments are not made), which more than “covers” the $1,360 Earnings-Limit-withheld benefits, and will begin receiving her monthly $2,000 checks in February 2019. In turn, in early 2020 Frankie will receive a subsequent "additional" payment of $640 that was effectively over-withheld from the first check of 2019 (since the reduction was only $1,360 but all $2,000 was withheld for that month).

Notably, the special Earnings Test rules that apply in the year a person attains Full Retirement Age somewhat favor those with birthdays earlier in the year. That’s because not only does the Earnings Limit “vanish” once an individual reaches the month in which they attain their Full Retirement Age (allowing someone to earn an unlimited amount of money without impacting their Social Security benefits), but also because the Full-Retirement-Age higher limit amount is not prorated. Thus, regardless of when, during the year, a person reaches their full retirement age, they may earn $46,920 prior to that month without an impact to their benefits.

Example 3b: Grace is an attorney at the same large law firm where Frankie works. Grace has $360,000 salary, paid in monthly installments of $30,000. She was born on February 2, 1953, and thus, will reach her birth-year-specific Full Retirement Age of 66 in February 2019. Grace decides she would like to begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits in January 2019, which prior to any impact of the Earnings Test, have been calculated to be $2,500 per month.

Grace will earn a total $30,000 in January 2019, the only month during the she in which she will work prior to reaching (the monthly in which she reaches) her Full Retirement Age. Since $30,000 is less than the $46,920 threshold amount for earnings in the year of (but prior to the month) Full Retirement Age, Grace will receive her full $2,500 Social Security benefit immediately in January 2019, and will continue to receive that benefit going forward after she reaches Full Retirement Age as well.

Special “Grace Year” Rule To Avoid The Earnings Test In The Year Of Actual Retirement

People retire at various times throughout the year for various reasons. But one beneficial aspect of the Earnings Test is that once an individual retires, they may claim a Social Security benefit that is not reduced by any income earned earlier in the year. Thus, even if an individual has already made substantially more than their Earnings Test threshold amount for the year, if they “hang up their hat” and retire, they can immediately begin to receive their (full and unreduced) Social Security benefits.

This benefit is applicable thanks to a special rule known as a “grace year.” The “grace year” is the first year in which an individual is entitled to a Social Security benefit and earns less than the “monthly limit” in at least one month (which would normally simply be the year they retire, but individuals may also have a grace year after a break in entitlement, as well as in the year certain benefits, such as a child’s benefit or mother’s/father’s benefit, terminate).

The “monthly limit” in a grace year is simply an individual’s applicable annual limit, divided by 12. Thus, for 2019, the monthly limit for an individual below Full Retirement Age for the full year is $17,640 / 12 = $1,470, while the monthly limit for an individual reaching Full Retirement Age in 2019 is $46,920 / 12 = $3,910.

Thus, (only) in an individual’s grace year, they are entitled to a “full”-unreduced-by-the-Earnings-Test monthly benefit for any month in which they did not earn more than the monthly limit.

Example #4: Fred is a successful Financial Advisor who is 64 years old. From the beginning of the year in January, through April when he sold his practice, Fred earned $250,000, exponentially more than his $17,640 threshold amount for 2019. However, under the special rules that apply in the grace year, Fred can retire in April and apply for Social Security benefits effective May 2019, and can immediately begin receiving benefits.

Note that Fred is entitled to use the special grace year rules because this is the first year that he was entitled to his retirement benefit and because earned less than the monthly limit in at least one month. Specifically, Fred’s benefits began after he actually retired, and thus, his monthly earnings in each of those subsequent months he received benefits was zero. (Note: If Fred wanted to, he could have continued to earn up to $1,470 or per month, after claiming benefits, and still avoided any impact of the Earnings Test in that year because this amount does not exceed his monthly limit amount.)

Special Grace Year Rules For Self-Employed Individuals

Determining when employment ends – and thus, for purposes of the grace year rule, when income was actually earned – is generally fairly straightforward for W-2 employees. If Social Security benefits begin after W-2 employment ends (i.e., after the date on which they terminate employment, presuming they don’t take a new job with new W-2 wages to report), it’s quite clear that the W-2 income doesn’t overlap benefits and won’t apply against (and certainly won’t exceed) the monthly limit.

On the other hand, determining retirement for self-employed individuals is a bit trickier. Social Security generally looks to see if a self-employed person renders “substantial services” during a month, and if such services are provided, the individual is not retired and the earnings may still count towards the grace year’s monthly limit in that month.

Substantial service is typically defined as devoting more than 45 hours per month to the business, or devoting more than 15 hours per month to the business if it is a highly skilled occupation. However, if a self-employed person can show that their monthly earnings are less than the $1,470 exempt monthly amount, they may be able to be considered retired as well, and receive Social Security benefits that are not reduced by the Earnings Test (regardless of how many hours they’re spending to reach that income level). Note, however, that in the Social Security Administration’s own words, “This exception to the 45-hour rule has limited application since, in most SE, the monthly earnings are not readily determinable.”

The Earnings Test Only “Cares About” Earned Income!

As the name implies, the Social Security Earnings Test – technically referred to as the “Annual Earnings Test”, or “AET”, by the Social Security Administration itself – is only concerned with earned income. In general, earned income is comprised of an individual’s net earnings from self-employment, plus any gross W-2 wages (i.e., not reduced by contributions to retirement accounts).

In limited circumstances, however, an individual may be able to exclude net earnings from self-employment and/or certain W-2 wages from being counted as “earned income” for purposes of the Earnings Test. Self-employment income, for instance, can be excluded from Earnings Test if an individual can “prove” that the income results from services performed before Social Security benefits were claimed (even if the income is received later).

Example #5: Caryn is a 64-year-old sole-proprietor CPA who decided to “call it quits” after filing the last of her client’s tax returns in October of 2018. In November of 2018, Caryn claimed Social Security benefits and thanks to the special year-of-retirement grace-year rule, she immediately began receiving a monthly benefit of $1,800 (since her earnings were $0 in the months when her benefits began).

However, some of Caryn’s clients “took their time” paying their invoices, though, and as a result, Caryn received $30,000 of payments for her 2018 tax services in early 2019. As a cash basis taxpayer, Caryn will report this income for 2019 (even though it was for services rendered in 2018).

Suppose that after factoring in a small amount of continued expenses, Caryn’s net profit from self-employment for 2019 is $27,460. Although that amount is $10,000 more than her $17,640 Earnings Limit for 2019, Social Security will not be required to withhold any of her benefits. Because even though Caryn will show a profit for tax purposes in 2019, the profit is really due to services performed in 2018 – prior to when Caryn claimed benefits – and thus, she should not be subject to the Earnings Test.

An exception for W-2 wages works in a substantially similar way. Essentially, if wages are received after retirement, but for work performed before retirement (e.g., post-employment severance payments), the wages do not count for purposes of the Earnings Test. Thus, as specified by Program Operations Manual System (POMS) Section Chapter RS – Retirement and Survivors Insurance, Section 02505.045(A), wages received for things such as “on account of retirement,” termination pay, accrued sick leave or vacation pay, and bonuses attributable to work performed in an earlier year should not reduce an “early” retiree’s Social Security benefits.

Of course, there’s no way for the Social Security Administration to know why wages were received, so in most cases, a beneficiary must tell them! With respect to explaining the nature of earnings (and trying to exempt them from the Earnings Test), an individual should file Form SSA-795 (Statement of Claimant or Other Person), and include information such as the amount of wages that should be excluded from the Earnings Test calculation and the reason such amounts should be excluded.

Notably, though, it’s specifically earned income that creates issues under the Earnings Test. A taxpayer can enjoy an infinite amount of income and enjoy a Social Security benefit that is not reduced by the Earnings Test as long as the other, non-Social Security income doesn’t consist of earnings from employment (at least, not greater than the individual’s earnings threshold for the year). Thus, for instance, an individual may receive a pension of any amount, or take distributions from a retirement account of any size, without fear of reducing their Social Security benefits. Similarly, investment income, such as interest, dividends, and capital gains, has no impact on the Earnings Test.

The Retirement Earnings Test Impacts Different Types Of Social Security Benefits Differently!

One of the challenges of Social Security planning is that “Social Security benefits” are not a singular type of benefit. Rather, the Social Security Administration is responsible for administering a number of discrete benefits, each with their own set of similar-but-not-the-same rules. Such benefits include an individual’s own retirement benefit, a survivor’s benefit, and so-called auxiliary benefits such as a spousal benefit and a child-of-a-retired-worker benefit.

Each of these benefits is impacted by the Earnings Test but in its own unique way.

Social Security Earnings Test Impact on Retirement Benefits

When it comes to an individual’s own Social Security retirement benefit – earned via their own work history – only that individual’s earnings will impact that individual’s retirement benefit. Thus, a pre-Full-Retirement-Age individual can receive a Social Security benefit that is not reduced by the Earnings Test, regardless of how much (or little) their spouse still earns. An individual’s spouse’s age would also be irrelevant in determining the impact of the Earnings Test on their own retirement benefit.

Example #6: Ben is 64 years old and has recently retired. Ben’s wife, Shannon, is a Senior executive at a large firm and earns $1 million per year. Despite Shannon’s high earnings, Ben may claim Social Security benefits without running afoul of the Earnings Test.

Social Security Earnings Test Impact on Survivor Benefits

Widowed individuals are eligible for Social Security survivor benefits, based on the deceased spouse’s earnings history, provided they were married to the decedent for at least 9 months prior to their passing (or less than 9 months in certain exceptions).

Individuals usually have a substantial amount of flexibility when it comes to survivor benefit planning. Unlike, for instance, the “deemed filing” that occurs when a person applies for either their own benefit or their spousal benefit – which automatically applies them for the other benefit as well (an exception to this rule is still available on or after Full Retirement Age for those who will turn 66 on or before January 1, 2020) – an individual can apply for only their own individual retirement benefit first, and later apply for and switch to their (higher) survivor benefit, or they can claim only their survivor benefit first, and later switch to their own (higher) retirement benefit.

Despite the flexibility of benefit selection for widows, though, they receive no such similar benefit when it comes to the Earnings Test. Instead, the Earnings Test will reduce a survivor benefit in the same way it would reduce an individual’s own retirement benefit. Thus, regardless of which benefit a pre-Full-Retirement-Age widow chooses to collect, any earnings above their applicable threshold amount for the year will reduce the amount of Social Security income that they receive if the benefits are received before Full Retirement Age.

Social Security Earnings Test Impact on Auxiliary (i.e., Spousal & Children’s) Benefits

In addition to being entitled to a benefit based on an individual’s own work history, or that of their spouse after the spouse’s death (i.e., a survivors benefit, discussed further below), sometimes a person is entitled to a benefit based on another worker’s earnings history while that worker is alive. These benefits, called “auxiliary benefits,” are also subject to the Earnings Test.

For instance, suppose Vance, who has worked for nearly 40 years, has recently begun to collect Social Security benefits based on his work record. Vance’s wife, Pam, never worked but has applied for Social Security spousal benefits. Meanwhile, Vance and Pam have a 14-year-old son, Jim, who is receiving child benefits, also based on Vance’s work record. In this situation, both Pam and Jim’s benefits are auxiliary benefits, because they are received based on Vance’s earnings record.

Unfortunately, the Earnings Test for auxiliary benefits can actually be even more problematic than its application to other (e.g., retirement or survivor) benefits. That’s because when it comes to auxiliary benefits, the earnings from both spouses (or really, either spouse) can impact auxiliary benefits!

Example #6a: Harry is closing in on 64 years old (pre-Full Retirement Age), and his wife, Sally, is 67 years old (post-Full Retirement Age). Harry is still working and has filed for his Social Security retirement benefit, and Sally, who chose to dedicate her life to volunteerism, has filed for her spousal benefit. Prior to the impact of the Earnings Test, Harry’s own benefit is $1,700 per month, while Sally’s spousal benefit would be $1,000 (which is 50% of Harry’s full $2,000/month Primary Insurance Amount, as while Harry’s benefit is reduced to $1,700 by retiring early, Sally’s spousal benefit remains the full auxiliary benefit because she is full retirement age).

Initially, Harry had planned to retire at the end of 2018, but his employer offered him a part-time position that Harry couldn’t pass up, and he decided to continue working in 2019. Harry’s salary in 2019 is $37,640, which is $20,000 more than his threshold amount of $17,640 for the year, and as a result, $10,000 of benefits based on his earnings record must be withheld. And more importantly, because Sally’s benefit is based on Harry’s earnings record, it means that when the Earnings Test reduces Harry’s benefits, it reduces Sally’s benefits as well!

In this case, the combined amount that Harry and Sally are supposed to receive, prior to the impact of the Earning test is $1,000 + $1,700 = $2,700 per month. Thus, since Social Security will not pay any benefits for any portion of a month where there is a reduction in benefits due to the Earnings Test, Harry and Sally would received no benefits for $10,000 / $3,700 = 3.704 (rounded up to 4 months) January – April of 2019, but would begin receiving Harry’s $1,700 retirement benefit and Sally’s $1,000 spousal benefit beginning in May 2019 (and would continue to receive those benefits through the end of the year).

Note that even though Sally, herself, has reached Full Retirement Age, because her Social Security benefit is entirely attributable to Harry’s work record, her spousal benefit is reduced alongside his own retirement benefit.

However, while the Earnings Test may reduce both a worker’s own retirement benefit and any auxiliary benefits paid based on his/her earnings record, the spouse’s own benefits are not reduced in situations where he/she is also eligible for their own benefits as well.

Example #6b: Jake is 68 years old (post-Full Retirement Age), and his wife, Melanie, is 64 years old (pre-Full Retirement Age). Both have filed for Social Security benefits.

Jake was modest earner throughout his career. Melanie, on the other hand, was a high-earner for many years, and has only recently begun to slow down, currently earning $31,640 per year. Prior to the impact of the Earnings Test, Jake is entitled to a $1,000 monthly retirement benefit on his own earnings record, and an additional $400 monthly spousal benefit (a total of $1,400/month), while Melanie is entitled to a $2,400 monthly retirement benefit.

In this scenario, Jake’s own retirement benefit of $1,000 would not be impacted by the Earnings Test, because that benefit amount is attributable to his own earnings record. However, both the $400 monthly spousal benefit to which he is entitled, as well as Melanie’s $2,400 monthly retirement benefit, would be impacted by her earnings (since she is under Full Retirement Age).

Melanie’s $31,640 is $14,000 more than her $17,640 threshold amount for 2019, and thus, Social Security must withhold $14,000 / 2 = $7,000 of benefits. In this situation, there are a total of $2,800 of benefits being paid that are attributable to Melanie’s earnings history, and thus, neither her own retirement benefit, nor the $400 spousal benefit for Jake, will be paid for the first $7,000 / 3 = 2.92 (rounded up to) three months of the year.

Therefore, from January through March, Jake would receive his monthly $1,000 retirement benefit (but only $1,000/month and not his total $1,400/month), while Melanie would receive no benefits at all. And from April through December, Jake would receive a $1,400 per month (his $1,000 retirement benefit plus his $400 spousal benefit), while Melanie would receive $2,400 monthly retirement benefit.

On the other hand, when the ages are reversed, and the primary earner (on whose earnings record the auxiliary benefits are being paid) is past Full Retirement Age (where the Earnings Test no longer applies), even otherwise-unreduced auxiliary benefits can still be reduced because the actual spousal recipient fails the Earnings Test themselves!

Example #6c: Jerry is 68 years old (post-Full Retirement Age), and his wife, Dorothy, is 64 years old (pre-Full Retirement Age).

Jerry was a high-earner throughout his career and is currently enjoying a monthly Social Security benefit of $3,000, in addition to his $15,000 per month salary. Similarly, Dorothy has also filed for Social Security benefits, while she is continuing to earn a $2,000 monthly salary, and is entitled to a combined $1,100 monthly benefit, consisting of a $400 retirement benefit, plus a $700 spousal benefit. At least, that’s prior to the impact of the Earnings Test.

Since Jerry has reached his Full Retirement Age, his earnings have no impact on either his own benefit, nor any benefit received by Dorothy. Dorothy, on the other hand, is under Full Retirement Age, and must therefore apply the Earnings Test to her benefits. And since Dorothy’s annual salary is $24,000, exceeding her Earnings Limit threshold of $17,640 by $6,360, the Social Security Administration must withhold $6,360 / 2 = $3,180 in benefits.

The end result is that Sally’s total monthly benefit of $1,100 will, therefore, be withheld for three months. Even though Jerry’s benefits will not be impacted at all.

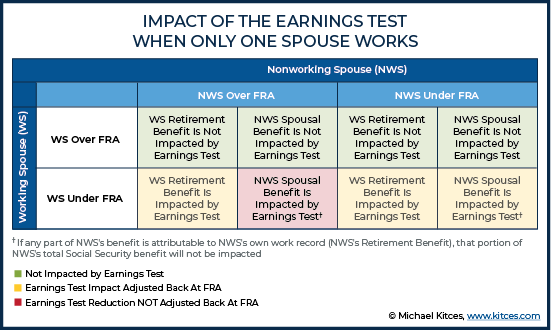

Social Security Planning For Couples When One Retires Early

When it comes to Social Security planning, reaching Full Retirement Age tends to “solve” a lot of “problems.” Because at that point, the Earnings Test no longer applies, regardless of one’s earnings from employment.

However, the challenge for couples, in particular, is that often one spouse retires while the other spouse continues to work. Which leads to a desire to begin claiming (and maximizing) Social Security benefits (in part to replace the one spouse’s lost wages), but can begin to run afoul of the Social Security Earnings Test, depending on whether the older or younger spouse is the one who retired while the other is still working.

In practice, if the spouse who continues to work is over Full Retirement Age, then all of the retirement and spousal benefits potentially available to the couple will be unimpacted by the Earnings Test… either due to the attainment of Full Retirement Age (for the working spouse) or the lack of any earnings (for the already-retired spouse). By contrast, however, if the working spouse is under Full Retirement Age, then that working spouse’s earnings will not only (potentially) impact their own retirement benefit, but also a spousal benefit claimed by either spouse. Thus, when a working spouse is under Full Retirement Age, but the couple is looking for additional cash flow via Social Security benefits, the only option at their disposal may be the nonworking spouse’s own individual retirement benefit based on their own prior earnings.

The Earnings Test Is Simply Forced-Delayed Retirement (With Recovery After Full Retirement Age)

While the Social Security Earnings Test is often framed as a “loss” of benefits, it’s crucial to recognize that in reality, such benefits are not necessarily lost. Because they are actually added back to a beneficiary’s subsequent benefits upon attaining Full Retirement Age.

However, any amounts that were previously withheld are not returned in a lump-sum. Rather, for every one month that benefits are not received early on account of the Earnings Test, one month’s penalty for claiming Social Security benefits early will be “reversed” once Full Retirement Age is reached.

Example #8: Carol is a waitress who will turn 66, and reach her Full Retirement Age, in September 2019. In 2015, upon reaching 62, Carol immediately applied for Social Security benefits based on her $1,000 Primary Insurance Amount (PIA). However, due to her early claiming of benefits at 62, she was only entitled to receive 75% of her PIA, or a $750 monthly benefit, prior to the application of the Earnings Test.

Suppose, however, that due to the Earnings Test, Carol received no Social Security benefits for 2 months in 2015, three months in 2016 and 2017, and 4 months in 2018. Thus, at the time she reaches Full Retirement Age, Carol will have “lost out” on a total of 12 months of Social Security benefits due to the Earnings Test, or a total of $9,000 (ignoring the impact of any Cost-Of-Living Adjustments).

To “return” these benefits to Carol, at Full Retirement Age, Social Security will “wave its magic wand”, and “poof!”, instead of treating Carol as though she claimed benefits as 62 (when she actually claimed benefits) for a 25% reduction, she will be treated as having claimed benefits 12 months (the number of months benefits were withheld due to the Earnings Test) later, at 63, which would have been only a 20% reduction for early benefits.

Since the difference in the actuarial reduction for claiming Social Security benefits at 63 as opposed to 62 is 5%, the original reduction in Carol’s monthly benefit will be reduced by 5% - from a 25% reduction of her PIA to only a 20% reduction instead – once she reaches her Full Retirement Age. Thus, Carol’s $1,000-reduced-to-$750 monthly benefit will become an $800 monthly benefit instead.

Notably, because of the way in which Social Security “returns” benefits that were lost due to the Earnings Test works, the ultimate harm – or benefit – caused by the rule depends on how long an individual lives after reaching Full Retirement Age. For instance, if Carol above were to die on her 66th birthday, she will have truly “lost” the $9,000 of cumulative benefits that were withheld by Social Security as a result of the Earnings Test (which she didn’t live long enough to get back after all).

If, however, Carol lived to be 91, she will have enjoyed 25 years x 12 months x $50 = $15,000 worth of additional Social Security benefits (ignoring the impact of any COLA)… meaning the Earnings Test would have actually helped Carol in the long run (since she only “lost” $9,000 as a young retiree due to the Earnings Test)! Just as delaying Social Security benefits helps anyone who lives past their life expectancy. And while it’s true that there are time-value-of-money factors to consider, those time-value-of-money factors are at least partially assuaged by the fact that any cost-of-living adjustments received after the adjustment at Full Retirement Age will be made to a higher benefit amount.

In essence, then, the Social Security Earnings Test is really nothing more than “forced delayed retirement” (or “forced less-early retirement”), compelling someone claiming benefits early to wait until Full Retirement Age after all (and literally get the benefit they would have gotten if they hadn’t retired early). Which ironically may turn out to their benefit anyway, if they live long enough (as it would have been for anyone who delays Social Security and lives a long time). Conversely, though, it also means that a retiree who does not live long enough after reaching Full Retirement Age to “recoup” previously withheld benefits really does finish at a financial loss (just as they would have by voluntarily delaying and then not living long enough to recoup the cost of delay).

In addition, the increase in benefits at Full Retirement Age only applies to the benefit that was reduced by the Earnings Test. So, for instance, if an individual receives a benefit that is not impacted by the Earnings Test (such as a divorced-spouse benefit for wages of an ex-spouse who was entitled to benefits prior to the month of divorce), there is no adjustment at Full Retirement Age (because there was no reduction of that benefit in the first place.

If, on the other hand, a widow retires early and is subject to the Earnings Test on her own retirement benefit, but later switches over to a higher widow’s benefit at Full Retirement Age, there will not be an adjustment to the survivor’s benefit (because it’s not the benefit that was withheld due to the Earnings Test). Thus, any of the widow’s own retirement benefits reduced/withheld from 62 through Full Retirement Age will have truly been lost.

And if a post-Full-Retirement-Age spouse has spousal benefits withheld because of a younger spouse’s earnings, the older, non-working spouse will generally never get those benefits back. Since they have already reached Full Retirement Age, they have already passed the point where an adjustment would be made, and thus, lost benefits are actually lost!

The key point, though, is simply that, because of the impact of the Earnings Test – and especially the potential impact to expected cash flow caused by the Earnings Test – it’s especially important for married couples to manage the Earnings Test when one spouse retires early!

Great article!

Any way you have access to a resource that shows that Spousal benefits withheld count toward the earnings test? I have a client that is battling Social Security on that. They’re withholding her benefit and her husband’s spousal benefit, but only counting her benefit toward the Earnings Test penalty

You never addressed the scenario about the child receiving benefits based on parent record where parent continues to work and has benefits withheld due to making income about limits. Is the child’s benefit also withheld?

The article says, “Notably, the special Earnings Test rules that apply in the year a person attains Full Retirement Age somewhat favor those with birthdays earlier in the year.” I agree that it can, but the opposite is also true.

Most people don’t make $46,920 per month, or even in two or three months. So people born in January through March could never take advantage of the full exempt amount, simply because they won’t earn that much between January 1 and the month of FRA. Someone attaining FRA in December and earning $40k a year can claim for the entire year with no reduction worries. I’d call having a late-in-the-year birthday more favorable in that situation. (That claiming strategy would make a ton of sense for someone who’s spousal benefit will be larger than their own, but who’s spouse has not yet claimed benefits.)

Fantastic article, Jeff – it was a doozy and took a few days to get through it all. 🙂

For the widow/survivor benefit, you mentioned that the “deemed filing” provision doesn’t apply and they can switch benefits from the survivor benefit and their own retirement benefit.

If the survivor claims the survivor benefit first, do they still get delayed retirement credits on their own record?

I haven’t had this situation come up with a client yet but interested to know for when it does.

Elliott, retirement benefits and survivor benefits might be thought of as “separate pools of money” at the SSA. Claiming one often has no effect on the other. So, yes, a survivor’s own retirement benefit still enjoys monthly increases even while receiving the survivor benefit. (I’m being pedantic in that description. Delayed Retirement Credits technically only refer to the increases after Full Retirement Age. The increases prior to FRA might be thought of us eliminating a penalty every month rather than getting an increase.)

Specific to the Earnings Test, survivor benefits are one area where reduced benefits truly can be lost. For example, a survivor takes benefits at 60 (earliest possible) knowing their own retirement benefit at 70 will be larger at which point they will switch. If Earnings Test reductions occur to the survivor benefit, they will start being repaid at FRA, but because the pay back is designed to occur over the duration of the life expectancy, and because the widow will only receive the survivor benefit for the months between FRA and age 70, most of the repaid benefits won’t happen. The repayments are specific to the “separate pool of dollars” of the survivor benefit and will not be applied to the retirement benefit.

Hello

The penalty for earnings in excess of the maximum allowable when beginning benefits prior to FRA, you said

“…reducing the actuarial reduction for claiming early by the number of months in which no benefits were received due to the Earnings Test.”

But what about months where a partial benefit was received? So let’s say that at 64 my SS retirement benefit is $2,000/mo but my earnings of $2,470 for the month exceeds the max of 17640/12 = $1,470, or exceed it by $1,000 thus reducing my benefit by 1000/2 = $500. How is this ‘lost’ $500 used in adjusting the actuarial determination of my benefit in the month I attain my FRA?

The following suggests that one does receive credit for partial reductions:

POMS RS 02501.021 The Earnings Test (ET)

C. Crediting Months and Adjustment of Reduction Factor (ARF)

A beneficiary will receive crediting months for any month he or she was in full or

partial work deduction due to excess earnings under the [Annual Earnings Test]. See RS 00615.482B. The beneficiary will receive a benefit adjustment, or ARF, if he or she has at least

one crediting month. This will provide a higher benefit amount by removing some or

all of the reduction factors from the initial payment calculation. See RS 00615.582B.2.

Kudos on a very clear and helpful article! After hours of searching (including SSA websites), this was the only article I found that spells out the impact (or, actually, lack of impact) on the spousal benefit when the working spouse is over the FRA and the non-working spouse is under the FRA.