Executive Summary

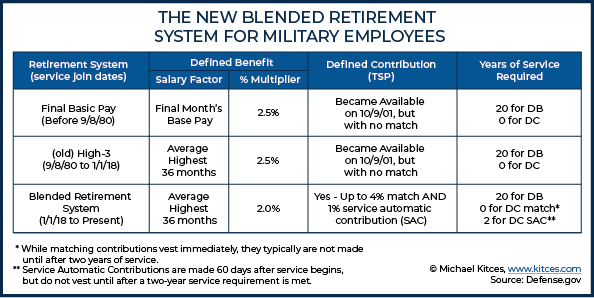

Since before World War I, the United States has maintained a retirement program in one form or another to incentivize military servicemembers to build long-term careers in the armed services. The last iteration of the military defined benefit retirement system, called the High-36 Retirement Plan (or “High-3”), was established after World War II and required servicemembers to serve at least 20 years before becoming eligible for retirement benefits. The High-3 system calculates retirement pay based on a percentage of the average salary from the highest 36 months (or 3 years, thus the name “High-3”), for those who have met the 20-year service requirement.

In this guest post, Kathleen Boyd points out that this requirement has been problematic, as according to the Department of Defense, an estimated 80 percent of military personnel exit their service before 20 years. Consequently, most servicemembers have departed the military without any retirement savings. To compensate for the all-or-nothing cliff vesting, the military began offering a Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) so that servicemembers could supplement their retirement benefits with their own tax-preferenced savings. However, the TSP under the original High-3 system offers no military contributions or matching elements on behalf of servicemembers; it’s ‘just’ a self-directed retirement savings plan. And consequently, it provided little to no incentive for a servicemember to initiate contributions if they weren’t already self-motivated to do so.

In 2016, Congress enacted substantial changes to the High-3 military retirement system for the first time since it was set up in 1981. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), effective January 1, 2018, was created with the goal of cutting expenses while increasing flexibility for servicemembers to participate and get at least some retirement benefits from the government. From that legislation, the new Blended Retirement System (BRS) was born.

The BRS consists of a blend of a new High-3 system, similar to the old but updated with a decreased defined benefit amount (due to an adjustment of the years-of-service multiplier), plus new provisions for servicemember TSP contributions (to supplement the reduced High-3 defined benefit amount), including a 1% service automatic contribution (‘free money’ that does not depend on the member’s contribution level) and an employer match of up to 4%. Additional benefits of the new BRS system include substantially increased contribution limits for servicemembers working in combat zones, and a potentially significant retention bonus.

Notably, while the 20-year service requirement still remains in place to receive the High-3 pension annuity benefit under the BRS, a servicemember can take the TSP funds (including their own contributions, government contributions, and matches) upon exiting the military (assuming they meet the vesting requirements – matching contributions vest immediately, and the 1% service automatic contributions vest after two years of service).

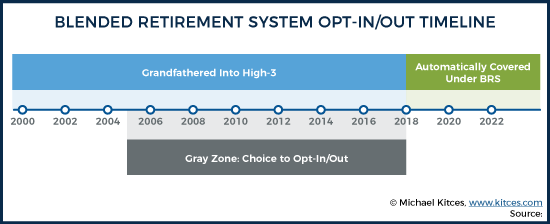

To facilitate the transition from the old High-3 to the new Blended Retirement System, the Department of Defense established a deadline of December 31st, 2018 for active servicemembers to make a decision on whether to opt into the new system or stay with the old. Yet even though the deadline for the choice has passed, it’s still important for advisors working with military clients to understand the benefits and risks of this irreversible decision for future planning purposes.

For example, if a servicemember opted into the new plan, they are now set to receive a lower defined benefit amount, but also have access to government contributions and a matching benefit to their TSP. Alternatively, if a servicemember chose to stick with the old High-3 plan, they stay on track to receive the higher defined benefit amount but lose out on government contributions and matches to their TSP.

The key point is simply that there are additional intricacies of the new system that advisors who serve servicemembers of the military need to understand, and that the servicemember’s join date and years of service will dictate not only which plan will apply to them, but also which benefits they will be eligible for. And while the 2018 deadline to choose retirement systems has passed, the decision must still be made by any Reserve members who are redeployed who have yet to make a choice.

How Military Members Traditionally Saved With the Final Basic Pay and High-36/High-3 Retirement Systems

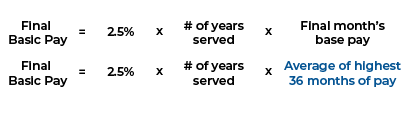

Historically, the military retirement system has been a government-funded, noncontributory, defined benefit system created to help incentivize servicemembers to choose a long-tenured career in the armed forces. After World War I, the military established the Final Basic Pay Retirement System, which introduced a standard calculation for retirement compensation based on a percentage of base pay and the number of years of service. Under this system, retired pay was computed by multiplying a servicemember’s final monthly base pay by 2.5 percent for every year of service.

In response to the increasing number of retirees, longer life expectancies, cost-of-living increases, and subsequent rising costs, the military later implemented a number of major retirement reforms in 1981, under a program called the High-36 Retirement System (High-3). This revised program changed the benefit formula to calculate servicemembers' final basic pay, based on the average highest 36 months of base pay, instead of just the final month of basic pay under the original Final Basic Pay System.

Example 1: Lieutenant Colonel Smith has met the key service requirement having served for 20 years, and the average of her highest 36 months of base pay was $9,244 (what an O-5 paygrade would actually receive at 20 years). Using the High-3 formula above, she would receive a monthly defined benefit of $4,622:

2.5% x 20 years x $9,244 = $4,622

Notably, in the rare case that a servicemember would earn enough years of credit, the monthly defined benefit amount could technically go all the way up to 100% of the average highest 3 years of salary. For 40 years of service, for example, the benefit under High-3 would be 100% of the High-3 base amount (40 years x 2.5% = 100% salary continuation under the High-3 system).

Over the years, the 20-year service requirement has become especially problematic, though, given the fact that most servicemembers do not actually meet the requirement, with an average service duration of 6-9 years, according to the Department of Defense. Consequently, the cliff-vesting nature of the High-3 system resulted in many servicemembers leaving their military career without any retirement savings, while the minuscule number of servicemembers who served 40 years or more would receive 100% income replacement. In essence, the High-3 system was an all-or-nothing proposition for most servicemembers.

To partially compensate for shorter-tenured servicemembers who disqualified from receiving the retirement annuity, access to the hallmark Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), which is the public sector’s version of the 401(k), was made available to the military in 2001. The TSP was designed to provide an optional way for servicemembers to supplement their monthly High-3 retirement annuity. Working similarly to a traditional qualified plan, the annual contribution limit is $19,000 (as of 2019), with a catch-up provision of up to $6,000 after age 50. The funds grow tax-deferred and can be withdrawn without an early withdrawal penalty at age 59 ½, with RMDs starting at age 70 ½. In addition, just as 401(k) plans offer both traditional and Roth-style contributions, so too does the TSP have both traditional (pre-tax) and Roth contribution options. The downside of a TSP under the original High-3 System is there is no matching element; the responsibility of contributing is solely on the servicemember.

Another important feature of the TSP relates to combat pay. Specifically, if a servicemember is deployed to a combat zone and receives (tax-free) combat pay, they become eligible for much higher contributions to the TSP – up to $56,000 (2019) in a calendar year (i.e., they may contribute their combat pay in addition to their normal annual limit, such that the total annual contribution to their account, including tax-deferred contributions, combat pay, service automatic contributions, and employer match does not exceed $56,000). This is significantly more than the regular TSP annual elective deferral limit of $19,000. The Department of Defense and the IRS have worked with Congress to define “combat zones.” Per the IRS, “The term ‘combat zone(s)’ is a general term that includes all of the following hostile areas where military may serve: actual combat areas, direct combat support areas, and contingency operations areas.”

Understanding the New Blended Retirement System (BRS)

In 2016, Congress passed additional military retirement reforms, with the purported goal of identifying ways for the Department of Defense to save money, while also increasing its flexibility to better mirror what retirement benefits are available to civilians. The FY 2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), enacted in 2018, established a revision of the High-3 system called the Blended Retirement System (BRS).

Under the new BRS, the High-3 retirement benefit consists of a reduced defined benefit monthly payout of 2.0 percent of pay, down from the 2.5 percent in the old High-3 system. Servicemembers under BRS would still need to meet a 20-year service requirement to receive this benefit.

Servicemembers who began their service before December 31, 2017, had an option to switch to the new BRS system or stay with the old High-3 system.

Example 2: Using the same facts for Lieutenant Colonel Smith from Example 1, above, here’s how much she would now receive under the new system:

2.0% x 20 years x 9,244 = $3,698

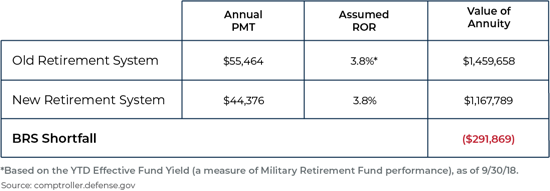

Recall that under the old High-3 system, Lieutenant Colonel Smith’s benefit was $4,622 – which means the new system has a more-than-$900 decline in monthly benefits! On a lump sum equivalent basis, the difference becomes even more distinct:

Reducing the multiplier from 2.5% (used in the High-3 formula) to 2% (used in the BRS formula) results in a 20% drop, almost $300,000 in our example, over the life of the annuity!

As noted earlier, to make up for this shortfall of a 20% reduction to the retirement pension under BRS, servicemembers are supplemented by a defined contribution plan, in which both the Federal government and the servicemember initiate contributions to a portable retirement savings account (Thrift Savings Plan). Once fully vested, the member’s contributions plus the government match made to the TSP would be for the member to keep once they transition out of the military, without being subject to the 20-year requirement.

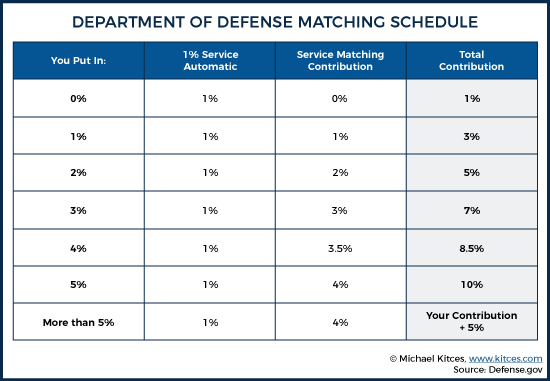

The exact vesting schedule for Federal government contributions to the TSP depends on which contributions are made. Specifically:

- Starting 60 days after a member enlists, an automatic government contribution of 1 percent of basic pay, referred to as a Service Automatic Contribution, is made to a member’s TSP (regardless of whether they make a contribution themselves). This is literally free money for all servicemembers under the BRS, and is not deducted from their pay. To become vested in the 1 percent Service Automatic Contributions, a member is required to have completed at least two years of service. If the servicemember already served two years before they opt into the BRS, they are considered immediately vested.

- If a servicemember elects to contribute a portion of their base pay into the TSP, the government will make a Service Matching Contribution from their 3rd year of service to the 26th year (i.e., servicemembers are not eligible for any matching contributions for their first two years). A servicemember is automatically vested in their own contributions and earnings inside the TSP, as well as the Service Matching Contributions and its earnings. Service Matching Contribution follows the same matching plan used for government civilians under the Federal Employee Retirement System (FERS):

- For every dollar the servicemember contributes up to 3 percent of their basic pay, the government will contribute a dollar.

- For every dollar a servicemember contributes beyond that, up to 5 percent of their pay, the government will contribute 50 cents. So if a servicemember contributes 5 percent of their basic pay in a pay period, the government will contribute a total amount equal to 4 percent of their basic pay (dollar for dollar matching on the first 3% of salary contributions, and 50 cents on the dollar for the next 2% of the servicemember’s salary contributions).

Example 3: Second Lieutenant Oliver has been in the service for five years and earns a salary of $48,143. Consequently, he will receive $481 as a Service Automatic Contribution into his TSP. In addition, Lieutenant Oliver contributes $10,000 of his own dollars into his TSP, for which he will receive a $4,000 Service Matching Contribution, which consists of a $3,000 match on the first $3,000 of his contribution (100% up to 3%) and a $1,000 match on the next $2,000 (50% up to 5% of the remaining contribution).

Since Second Lieutenant Oliver has been in the service for five years, he is fully vested in the Service Automatic Contribution (the two-year vesting requirement has been met), as well as the Service Matching Contribution (immediately vested). If he had only served in the military for one year, he would not be entitled to the $481 Service Automatic Contribution; and while he would technically be fully vested in any matching contributions in his account, none would be made until after he served for two years.

Other notable changes under the new Blended Retirement System include:

- Unless a different fund (or mix of funds) is selected by the servicemember enrolled in BRS, all TSP contributions will automatically be made to the ‘Lifecycle’ (or ‘L’) Fund by default. Similar to a target-date retirement fund, the L Fund is made up of a blend of the five TSP asset class funds, and is allocated based on the servicemember’s age. It is rebalanced over time, with an allocation objective of being less risky as retirement approaches. For non-BRS servicemembers, the default fund will remain the ‘Government Securities Investment’ (or ‘G’) Fund, consisting of “a non-marketable short-term U.S. Treasury security that is specially issued to the TSP.

- After meeting the 20-year requirement, a servicemember has a choice to receive their new High-3 defined benefit in the form of full monthly retired pay upon retirement, or to elect to receive reduced pay plus a partial lump-sum. If the lump sum is chosen, the servicemember will need to decide if they want 25 or 50 percent of their future retirement payments, which are discounted to present value, upfront. The tradeoff of taking the lump sum is that the servicemember’s monthly retired pay would then be 75 or 50 percent of the full value of their monthly retirement annuity, until full retirement age as determined by Social Security (67 for most servicemembers). At full retirement age, the monthly pension payments are restored to 100%. (It’s important to note that the lump sum is considered taxable income that could potentially push a servicemember into a higher tax bracket).

- Eligibility to receive a one-time retention bonus called “continuation pay” that is paid between the 8th and 12th year of service. This bonus can range from 2.5 to 13 times the monthly base pay, and comes with a minimum 4-year additional active duty service obligation. If the service obligation is not met, the servicemember may be required to repay some or all of the bonus, depending on their situation. The pay rate multiplier is based on service-specific needs, specialty skills, and hard-to-fill positions, with each branch of service determining its own guidance on continuation pay rates. The one-time payment is taxable, but can be split up to four equal installments over a four-year period to help reduce the tax liability. The continuation bonus can be used for anything (e.g. car, first home), and can even be contributed directly into the TSP, as long as the annual contribution limit hasn’t yet been reached.

Example 4: If Lieutenant Miller has served 8 years, is at an O-3 pay grade of $6,241.50/month, and is eligible for a 9 times multiplier, she would receive a retention bonus of $6,241.50 x 9 = $56,173.50. Once she receives her continuation pay bonus, she will have an additional four-year active duty service obligation. And because the lump sum payment would bump her into the next higher tax bracket, she has opted to receive four annual payments of $56,173.50 ÷ 4 = $14,043.38 over the next four years.

Practical BRS Planning Issues for Servicemembers

The Department of Defense provided a deadline of December 31st, 2018 for servicemembers with fewer than 12 years of service as of December 31, 2017, to either opt into the new BRS plan or remain grandfathered under the old High-3 plan. Notably, servicemembers who left the military (prior to January 1, 2018) and rejoined (or who will rejoin) after the opt-in decision deadline year (2018), have 30 days upon re-entry to decide whether to stay in the legacy system or elect the new BRS, so long as the servicemember previously met the requirement of having had fewer than 12 years of service as of December 31, 2017. And, according to the Department of Defense Office of Financial Readiness, “if you’re a cadet or midshipman attending a Service academy as of December 31, 2017, or are in the Reserve Officer Training Program with a signed contract as of Dec. 31, 2017, you’re also grandfathered under the legacy retirement system. However, if commissioning (or being placed in pay status) occurs after the 2018 opt-in window, you’ll have 30 days upon commissioning to opt into the BRS.”

For active servicemembers who enter the Uniformed Service before January 1, 2018 with at least 12 years of service, the deadline was moot as they were automatically grandfathered into the old High-3 plan. Similarly, all servicemembers who joined (or will join) on or after January 1, 2018, can also ignore the deadline as they are automatically covered under the new BRS, and are automatically enrolled at a default 3 percent contribution rate to their TSP – there is no waiting period. Nevertheless, the servicemember would still need to manually elect to have their contributions increased to 5 percent in order to get the full 4 percent government match (which, as mentioned earlier, begins with the member’s third year of service).

For a military member who started service before December 31, 2017 and decided to opt in to the new BRS, they would become subject to the lower defined benefit payout percentage of 2.0 percent, the government would have then begun initiating a Service Automatic Contribution of 1 percent of their pay into the member’s TSP, and finally, if the servicemember elected to make contributions to the TSP, the election would have been matched up to an additional 4% of their pay. Notably, unlike servicemembers who are automatically enrolled in the BRS, those who choose to opt in to the BRS are not automatically enrolled to make TSP contributions, and must manually elect their own personal contributions on the TSP.gov website.

Servicemembers also have the option to cancel their personal TSP contributions at any time. Even though matching contributions will stop once the member stops contributing, the 1% Service Automatic Contributions will continue to be made. Additionally, for members who entered the service on or after January 1, 2018, if TSP contributions are not being made at the end of any given year, the member will be automatically reenrolled at the same default 3% contribution level in January of the following year. And while a servicemember is given a short window to request a refund of automatic contributions made after initial enrollment into the TSP, they are not permitted a refund of contributions made due to automatic reenrollment once they elect to stop contributions. Therefore, if a servicemember wants to permanently opt out of making TSP contributions, they will need to stop automatic contributions every year before they start.

Furthermore, whereas the federal government alone manages investment of assets in the legacy High-3 pension plan, servicemembers under the BRS will be responsible for selecting from the fund options inside their TSP, which effectively shifts more of the investment risk from the federal government onto the servicemember.

It's important to note that new servicemembers of the Reserve need to be particularly careful with their TSP contributions, especially if they’re contributing to outside employer retirement plans. A TSP and a civilian employer-sponsored qualified plan like a 401(k) share the same Section 402(g) annual contribution limit per person. This means that a servicemember under 50 years of age cannot contribute more than the annual addition limit of $19,000 across both accounts in any given calendar year (with the exception of those serving in combat zones). While this doesn’t impact most active-duty servicemembers with one job, it is important to note for servicemembers who transition from the military in any given year, as well as members of the Guard and Reserves, as they often have access to other retirement plans through their full-time civilian jobs.

While the TSP system will not allow a servicemember to contribute over the maximum annual limit to the TSP, it does not have insight into any other retirement accounts the servicemember may have. If a servicemember reaches their annual addition limit because of contributions made to other qualified retirement plans before the final pay date of the year, they risk losing out on matching contributions made to the TSP. Junior servicemembers should also consider having their contributions automatically directed into a Roth TSP account, as this could be more advantageous to them as their salary rises and they subsequently move into higher tax brackets.

Under the old High-3 system, approximately 80 percent of servicemembers who joined the military ended out separating with no government retirement benefits, according to the Department of Defense. The military projects that under the new BRS, about 85 percent of servicemembers will receive at least some government retirement benefit if they serve at least two years, even if they don’t qualify for the retirement annuity.

The BRS also creates greater incentive for servicemembers to contribute their own pay to the TSP through matching funds offered by the federal government, as well as the Continuation Bonus pay. Depending on their pay grade and pay growth over the 20-year period, if a servicemember is consistently able to max out their contributions to receive the full 4% match for total annual contributions of at least 10 percent of their base pay (which includes the 1% Service Automatic Contribution), that plus favorable market performance and compounding returns could help make it a comparable alternative to the older High-3 system, per the DOD.

Ultimately, the Blended Retirement System offers portability of benefits to servicemembers who don’t serve long enough to retire from the military. And while the servicemember still needs to meet the 20-year service requirement to receive the retirement annuity, the new system virtually eliminates the “all or nothing” cliff-vesting nature under the old system because if a member does leave early, the BRS ensures they get to walk away with something – at minimum they can take with them the Service Automatic Contribution of 1 percent made on their behalf to their TSP, as long as they served for two years. This expansion of government retirement benefits is what makes the BRS an appealing “all-or-something” proposition.

Great recap, I was disappointed so few eligible service members opted-in and in general fail to take advantage of the TSP. I understand the point that for Reservists/NG, 5% Government contribution may not be impactful, but I do think over 20+ years, invested smartly and with a deployment or two you could smartly use the low-fee TSP as a main component of your retirement income.

As a CFP and servicemember I have a somewhat conflicted view on BRS. Will it be better for the majority of younger military members? yes. Does it also save our federal government significantly in terms of reducing future obligations and shifting the risk? Also yes.

However, the take rate (reflected by those who ‘opted-in’ to BRS) was less than 1/3 of what they expected. Why? this was simply too complicated of a decision for those in the target demographic to make. Most of those in their early career (0-5 years) don’t know if they are going to stay until 20 – I wasn’t planning on it and yet here I am nearing retirement. No one knows what the market will do over that time period and the default BRS rate of return for their breakeven analysis was set at over 8% I believe.

Further, BRS is not nearly as attractive for those in the Guard or Reserves like myself. We likely already have access to a retirement plan through our primary employer that offers some sort of employer contribution. My monthly paycheck as a part-timer is a fraction of that of my active duty peers – hence the potential 5% matching is not nearly as significant.

Last, the lump-sum option presents a potential landmine in my opinion and will drive poor decisions. Many military members wait 20+ years to buy their dream home or start a business, and will view this as an easy source of capital which obviously comes at a cost as the discount rate for those retiring this year is set at 6.81% and I believe it was even higher last year.

For those reasons, I’m not surprised that the vast majority of the military professionals that I interact with (Reserve, NG, and active duty officers and NCO’s with 10+ years of service) opted out and I’m glad I didn’t have to make this decision as a young lieutenant!

Excellent description of the system and decisions. No emotions attached (Unlike some of the discussions from former military). The old system (that I retired under) was great for those that served 20+ years and was an incentive to stay. But those that stay usually do so because they love serving. Once one factor in an appropriate servicemember contribution to get all that the Government will provide as a minimum, the results can be very effective. Some folks forget that those retiring after 20 years in service usually are about 40 years old! They aren’t retiring; they are just changing jobs and have a nice supplement coming when they really need it.

Kathleen-Great article. A couple of other important inclusions with the BRS. All contributions for BRS participants will be allocated to the age appropriate lifecycle fund, unless another investment option is selected. This is a big improvement on the current system where the G Fund (short-term U.S. treasuries) is the default for contributions. Servicemembers in BRS will also automatically be enrolled to make 3% contributions each year and even if they opt-out one year, they will be reenrolled in each subsequent year.

Thanks for reading the article and for the great feedback, Jonathan! These are definitely important details and we have incorporated them into the article.

-Erica

Senior Technical Editor, Nerd’s Eye View Blog, http://www.kitces.com