Executive Summary

To help mitigate the tax consequences of inheriting a potentially large pre-tax retirement account, the Internal Revenue Code permits spouses to roll an inherited retirement account over to his/her own IRA, and other “non-spouse” beneficiaries are permitted to at least “stretch” distributions out over their life expectancies as well.

However, the favorable rules for a so-called “stretch IRA” do not automatically apply to all inherited retirement accounts. In the case of an inherited employer retirement plan – such as an inherited 401(k) or inherited 403(b) account – the employer has the option to force non-spouse beneficiaries to use the far-less-favorable “5-year rule” instead, compelling the entire account to be liquidated by the end of the 5th year after death.

Fortunately, though, since 2010 employer retirement plans are required to at least permit a non-spouse designated beneficiary to complete a trustee-to-trustee transfer to an inherited IRA, preserving the ability to complete a stretch. On the other hand, the transfer provisions are only available to the original beneficiary of the inherited employer retirement plan, and not any successor beneficiaries (who can continue the stretch if available, but only from the original account).

On the plus side, though, the rules permitting a transfer from an inherited employer retirement plan to an inherited IRA also allow the assets to be shifted to an inherited Roth IRA, effectively giving the beneficiary the option of doing a Roth conversion even after the death of the original account owner. This is a strategy uniquely available to beneficiaries of inherited employer retirement plans, as an inherited IRA may not be converted to a Roth. The caveat, however, is that just because it’s possible for a beneficiary to convert doesn’t mean it’s wise to do so; since an inherited Roth IRA (after conversion) still has required minimum distribution obligations, it will usually be preferable to convert any other type of pre-tax retirement account first!

Stretch IRA Distribution Requirements For Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

While the tax code allows special rules for spouses to roll over an inherited IRA into his/her own IRA, in the case of any other beneficiary who is not a spouse (i.e., a “non-spouse” beneficiary), an inherited IRA must be distributed to the beneficiary.

However, IRC Sections 408(a)(6) and 401(a)(9)(B) allow a non-spouse beneficiary to “stretch” out those inherited IRA distributions over a period of time. Specifically, the rules stipulate that each year the non-spouse beneficiary is only required to take out an annual amount based on his/her life expectancy, beginning in the year after the original IRA owner’s death (at least, as long as Congress doesn’t change the rules to eliminate the stretch option!).

This “required minimum distribution” for the beneficiary is calculated similar to the rules for required minimum distributions during life, where the RMD is determined by taking the prior year’s December 31st (12/31) account balance, and dividing into it a life expectancy factor (also known as the “applicable distribution period”) based on the beneficiary’s age at the end of the current year. However, for a living IRA owner, the applicable distribution period is based on the Uniform Life Table (which is technically the joint life expectancy of the account owner and a hypothetical beneficiary who is 10 years younger). In the case of an inherited IRA, the non-spouse beneficiary’s applicable distribution period is simply based on his/her own single life expectancy (using Table I of Appendix B in IRS Publication 590). In each subsequent year, the life expectancy factor is reduced by 1, ensuring that the entire account will be liquidated over the applicable distribution period.

Example 1. Jeremy is 37 years old, and recently inherited a $300,000 IRA from his father who passed away in 2015 (the account was up to $305,000 by the end of 2015). Since his father passed away in 2015, the first year for required non-spouse beneficiary distributions is 2016. Jeremy will turn 38 years old in November of this year (2016), so his applicable distribution period is determined based on that age (even though he’s still 37 today). For a 38-year-old, the single life expectancy factor is 45.6, which means Jeremy will be required to take out $305,000 / 45.6 = $6,689 for his first RMD, or about 2.2% of the account balance. Next year, Jeremy’s life expectancy factor will be 44.6 (by subtracting 1 each year), then 43.6, then 42.6, etc., until in the 46th year the factor will drop below 1 and Jeremy will be required to take out the entire remainder of the account balance.

Notably, the requirement for a non-spouse beneficiary to take out a minimum distribution is only a minimum requirement (albeit one subject to a 50% penalty if missed and not fixed!). Jeremy can still take out more, any time he wishes. To limit the beneficiary’s withdrawals to only the RMD amount, it’s necessary to either use a “see-through” trust as the beneficiary of the IRA (so the trustee controls the pace of the distributions), or instead an IRA annuity with a restricted beneficiary payout (which prevents the beneficiary from accelerating the distributions).

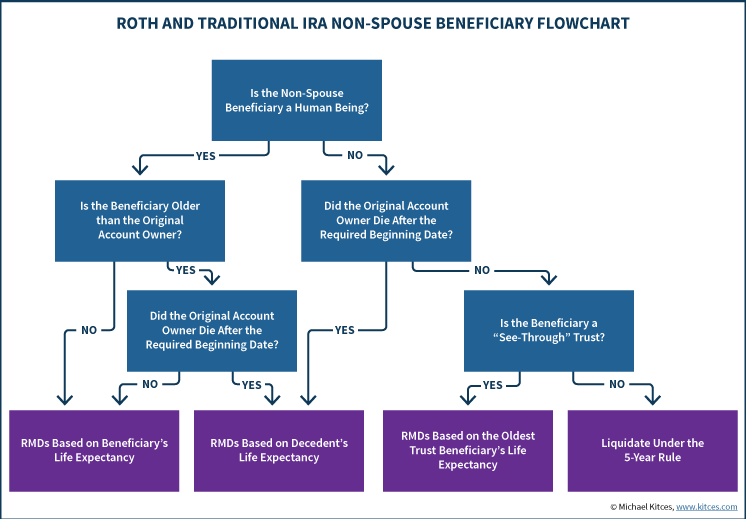

In the scenario where the original IRA owner died after his required beginning date (April 1st of the year after turning age 70 ½, when the original owner’s RMDs would have begun), the non-spouse beneficiary has the option of taking distributions over either his/her own life expectancy, or the remaining life expectancy of the original owner (under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-5). This is generally only helpful in situations where the original account owner died after his required beginning date, and leaves the IRA to an even older non-spouse beneficiary (who therefore has a shorter life expectancy, such that it’s more appealing to use the decedent’s longer life expectancy instead).

In the event that the non-spouse beneficiary is not a living, breathing human being with a life expectancy, but instead is a non-living entity (e.g., the estate, or a charity, or a trust that does not qualify as a see-through trust), there is no annual required distribution obligation, but the entire account must be liquidated by the end of the 5th year after death. (If the decedent passed away after his required beginning date, the account instead has annual distribution requirements, but based on the decedent’s life expectancy, which won’t be much better than 5 years!)

Notably, in the case of an inherited Roth IRA, the “stretch” rules also apply. While a Roth IRA is not subject to required minimum distribution obligations while the account owner is alive, after death an inherited Roth IRA is also subject to the exact same RMD obligations for a non-spouse beneficiary (under IRC Section 408A(c)(5)). Of course, the income tax treatment is different of those RMDs is different, because qualified distributions from a Roth IRA are tax-free (once the 5-year rule is satisfied), while the RMD from a traditional IRA is taxable. But the “special” treatment that a Roth IRA is “not subject to RMD obligations” applies only while a Roth IRA owner is alive, not after death.

Complications When Trying To Stretch An Inherited 401(k) Plan

When it comes to an employer retirement plan, the rules that permit the “stretch IRA” treatment are equally available to a 401(k), 403(b), or other qualified plan as well. In fact, technically the rules permitting a non-spouse beneficiary to stretch an inherited retirement account applied first to employer retirement plans (under IRC Section 401(a)(9), which defines the rules for all employer retirement accounts); it was only later that IRC Section 408, which established the IRA, cross-applied those rules for the inherited IRA as well.

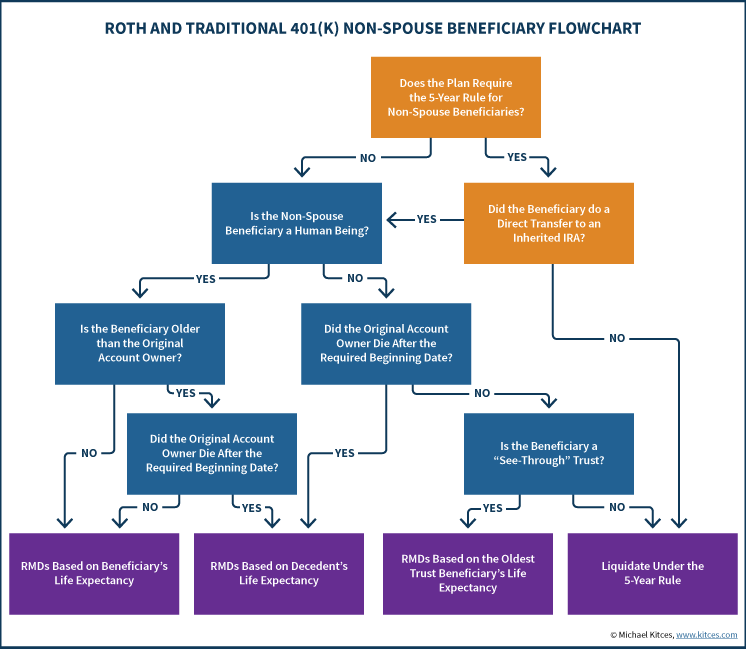

However, an important caveat in the context of employer retirement plans is that while it is an option to provide beneficiaries the opportunity to stretch the account over life expectancy, the plan is not required to offer the choice. Instead, under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-3, Q&A-4, an employer retirement plan is permitted to eliminate the stretch option, for some or all employees, and instead require that beneficiaries who keep their assets in the plan must follow the 5-year rule (that the inherited retirement account must be liquidated by the end of the 5th year after death).

The basic purpose of this rule was/is fairly straightforward: to relieve employer retirement plans from being saddled with the administrative costs to implement what could be 50+ years of stretch distributions to the beneficiary of an employee who only worked for the company for less than a year in the first place. Otherwise, employer retirement plans could face an ‘undue’ burden of administering long-term stretches to short-term employees (who happened to pass away while being employed there).

For spousal beneficiaries, this has not necessarily been a problematic limitation, because the spouse can still do a rollover out of the plan, and over to his/her own individual IRA (and then wait until age 70 ½ to take RMDs under the normal rules for his/her own account). For a non-spouse beneficiary, though, a spousal rollover isn’t an option, and historically that meant the assets were “stuck” in the plan, such that the 5-year rule was the only option (even though, if the employee had rolled the money to an IRA beforehand, a stretch would have been available).

Example 2. Continuing the earlier example, if Jeremy’s father had his assets not in an IRA named for Jeremy’s benefit, but a 401(k) for which he was the beneficiary instead, the situation may be different. While the tax code permits the stretch 401(k) as a possibility, it’s up to the employer retirement plan as to whether it will provide the option to Jeremy. If the 401(k) plan allows for an inherited 401(k) stretch, then Jeremy may do so. But if the 401(k) plan dictates that Jeremy must use the 5-year rule, then he has no choice but to proceed accordingly. As a result, his father’s entire account balance will have to be distributed to him by the end of 2020 (the 5th year after death).

Trustee-To-Trustee Transfers Of Inherited Employer Retirement Plans To Stretch An Inherited IRA

To remedy the situation where beneficiaries might be stuck with an undesirable 5-year rule for an inherited employer retirement account, Section 829 of the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) created IRC Section 402(c)(11), which provided that employer retirement plans would be allowed to offer non-spouse beneficiaries the opportunity to complete a rollover of the inherited 401(k) or inherited 403(b) balance over to an inherited IRA (from whence the account could subsequently be stretched).

However, in follow-up IRS Notice 2007-7, the IRS declared that it was optional for plans to offer such rollovers (which meant that non-spouse beneficiaries might still be stuck, and wouldn’t know until after the fact). In response to complaints that wasn’t Congress’ intent, the IRS indicated that it would make the rule mandatory for plans, but then back-tracked and said it would remain optional, until eventually under Section 108 of the Worker, Retiree, and Employer Recovery Act of 2008 (WRERA) the rules were made mandatory for employer retirement plans to offer an inherited IRA rollover option (beginning in 2010).

Thus, under current law, the final version of IRC Section 402(c)(11) requires employer retirement plans to cooperate with non-spouse beneficiaries who wish to transfer an inherited employer retirement account to an inherited IRA.

Notably, though, an outright distribution of an employer retirement account to a beneficiary is treated as an irrevocable distribution not eligible for rollover under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(C). Instead, to receive favorable treatment, the transfer must be done as a direct trustee-to-trustee transfer from the inherited employer retirement plan to an inherited IRA, which under IRC Section 402(c)(11)(A)(i) will be treated as an eligible rollover distribution (allowing it to be contributed to the IRA).

In other words, an employer retirement plan that doesn’t offer non-spouse beneficiaries the option to stretch an inherited employer retirement account must provide the opportunity to do a trustee-to-trustee transfer to an inherited IRA instead (where it can be stretched). But the transfer is only valid when done as a trustee-to-trustee transfer, where the distribution check is made payable directly to the new inherited IRA account; if the beneficiary takes possession of the money, it is permanently and irrevocably distributed and ineligible for rollover.

Example 3. Continuing the prior example, while Jeremy’s inherited 401(k) plan may require him to use the 5-year rule if he keeps the assets in the plan, it cannot prevent him from doing a trustee-to-trustee transfer to an inherited IRA, which would be titled as an inherited IRA, in the name of the Jeremy’s father (the decedent), for Jeremy’s benefit (as the beneficiary). However, to complete the transfer, Jeremy must first open the inherited IRA at the new custodian, and then request that the inherited 401(k) plan distribute all its assets with a check payable directly to the new IRA. Notably, it’s permissible for the check to be sent directly to the new IRA custodian, or to Jeremy himself, as long as it’s made payable to the new IRA account.

Limitations Of The Non-Spouse Transfer Rule With Successor Beneficiaries

Notably, one caveat to the rule permitting a non-spouse beneficiary to complete a direct trustee-to-trustee transfer of an inherited employer retirement plan is that the individual must be a “designated beneficiary of the employee” in order to do so. In other words, he/she must be the beneficiary who was actually named in the beneficiary designation document itself, by the original account owner/employee, and not merely be a successor to the “original” designated beneficiary.

This creates potential complications in situations where the original designated beneficiary passes away, and a new “successor” beneficiary steps in place. Because while the new successor beneficiary is permitted to continue the applicable distribution period of the original beneficiary, the ability to transfer the assets of the inherited 401(k) to an inherited IRA dies with the original beneficiary.

Example 4. Continuing the earlier examples, assume that Jeremy names his 10-year-old daughter Kate as the beneficiary of his father’s (Kate’s grandfather’s) inherited 401(k), and Jeremy then unexpectedly passes away 2 years later (in 2018). In this scenario, Kate will be eligible to continue Jeremy’s original applicable distribution period, which was 45.6 years in the initial year of distribution (2016), and would have been down to 43.6 years in 2018. Thus, in 2019, Kate would face her first required minimum distribution as a successor beneficiary, and would use the 42.6 life expectancy factor (continuing to reduce each subsequent year by 1).

However, Kate can only continue to stretch her grandfather’s inherited account if the account was eligible to stretch in the first place. If the original inherited 401(k) plan had been transferred to an inherited IRA for Jeremy’s benefit, then Kate will be assured of her ability to continue the stretch from that inherited IRA. However, if Jeremy left the assets sitting in the original inherited 401(k), and that plan did not permit a stretch because it chose to be more restrictive and force the 5-year rule instead, then Kate will be “stuck” with the 5-year rule as well. Kate cannot do a trustee-to-trustee transfer to an inherited IRA after Jeremy passes away, because Jeremy was the “designated beneficiary of the employee [Jeremy’s father]”, while Kate is not (she’s merely Jeremy’s successor beneficiary). The transfer must have been done by Jeremy himself, while he was still alive.

Given the dynamic illustrated above, it’s important to recognize that even if the beneficiary of an employer retirement plan doesn’t care about a stretch and is content with a plan that only offers the 5-year rule, it may be desirable to transfer the money to an inherited IRA, just in case the beneficiary dies before the account has actually been liquidated and a subsequent successor beneficiary might want to stretch instead. Similarly, it may be preferable to transfer an inherited employer retirement plan to an inherited IRA to provide greater investment flexibility to subsequent beneficiaries, as even if the plan allows a stretch, the successor beneficiary may wish that the funds could be held in an inherited IRA with more investment choices than “just” what the employer retirement plan offers.

The Designated Beneficiary Determination Date

On the other hand, the problematic situation of successor beneficiaries “stuck” with the original inherited employer retirement plan only applies if the original designated beneficiary passes away after the “beneficiary determination date” which, under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A-4, is September 30th of the year after the death of the original retirement account owner.

Thus, if the named beneficiary dies before this date, he/she is simply not considered a beneficiary at all for determining the stretch period; instead, the contingent beneficiary named in the original employee’s designated beneficiary form will be substituted instead, and that person's life expectancy will be used instead (though the original beneficiary, or rather his/her estate, still has the legal right to the inherited dollars!).

Example 5. Continuing the earlier examples, assume that Jeremy passed away not in 2018, but in the summer of 2016, barely a year after his father died in 2015. In this scenario, the beneficiary determination date has not even been reached (since it would have been September 30th of 2016, given that Jeremy’s father died in 2015). Thus, while Jeremy will be the beneficiary for the purposes of determining who gets the money (or his estate after his death if no successor beneficiary had been named), Kate's life expectancy would be used to determine the stretch period (presuming she was named as contingent beneficiary on the original account).

Post-Death Roth Conversions Of Inherited Employer Retirement Plans

One unique opportunity that applies to an inherited employer retirement plan, which is not available to an inherited IRA, is the ability for a beneficiary to do a Roth conversion and create an inherited Roth IRA after the death of the original account owner.

The reason for this distinction is that technically, a(ny) Roth conversion is treated as a rollover distribution from an existing retirement account, that “happens” to go to a Roth IRA instead. In other words, from the tax code’s perspective, a Roth conversion is simply an IRA rollover where the destination IRA is a Roth IRA instead of a traditional pre-tax IRA.

Except in the case of an inherited IRA, a rollover is explicitly forbidden by IRC Section 408(d)(3)(C). An inherited IRA can go through a trustee-to-trustee transfer to another IRA custodian, but technically a trustee-to-trustee transfer is normally not treated as a “rollover”. Which means there’s no way to do a Roth conversion of an inherited IRA, because any attempt to do a rollover to a Roth IRA would be treated as an irrevocable distribution not eligible for rollover.

Normally, the same would be true of an inherited employer retirement plan, except that in order to facilitate the transfer from such a plan to an inherited IRA, IRC Section 402(c)(11)(A)(i) explicitly says that those trustee-to-trustee transfers are also treated as an eligible rollover distribution. Which means the funds coming out of an inherited employer retirement plan could go to an inherited IRA, or be treated as a rollover to an inherited Roth IRA instead.

In other words, a rollover from an inherited employer retirement plan to an inherited Roth IRA represents the one scenario where a beneficiary can actually do a Roth conversion of an inherited account, after the death of the original owner. But in order to do so, the transfer must be permitted in the first place (which means it must be done by the designated beneficiary, not a mere successor), it must be from an inherited employer retirement plan (not an inherited IRA), and it must go directly to the (new) inherited Roth IRA (as if it’s rolled to an inherited IRA first, it’s “stuck” there unable to be converted later).

Ironically, though, the mere fact that an inherited employer retirement plan can be converted to an inherited Roth IRA doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a good idea to do so. Converting to a Roth IRA – whether as the original account owner, or the beneficiary – is still only desirable if the conversion today can be done at a lower tax rate than would have applied in the future. So at best, a beneficiary would only want to do such a conversion if could be timed for a low-income year, or perhaps stretched out over time in a series of systematic partial Roth conversions to remain in the lower tax brackets.

In addition, as noted earlier, the reality is that the beneficiary of an inherited Roth IRA is still subject to post-death required minimum distributions, just like the beneficiary of any inherited retirement account (and unlike an individual’s own Roth IRA, which does not have any RMD obligations as long as the account owner is alive). As a result, for someone who is interested in doing a Roth conversion in the first place, it’s better to convert some other individual IRA into a Roth IRA (with no required distributions), rather than an inherited 401(k) into an inherited Roth IRA (which is self-liquidating with beneficiary RMDs).

Nonetheless, it should be recognized that doing a Roth conversion of an inherited employer retirement plan (401(k), 403(b), or other qualified plan) is a unique opportunity available only for such inherited plans, and not to any form of inherited IRA. The account will still be subject to RMD obligations as an inherited Roth IRA, making it less desirable to convert than other inherited retirement accounts, but could be appealing nonetheless if there are no other dollars available to convert at all!

Of course, the caveat remains that all of these stretch IRA strategies are only effective as long as Congress allows the stretch rules to remain available in the first place!

So what do you think? Have you ever done a post-death stretch from an employer retirement plan? Do you prefer to transfer the inherited employer retirement plan to an inherited IRA anyway, just in case?