Executive Summary

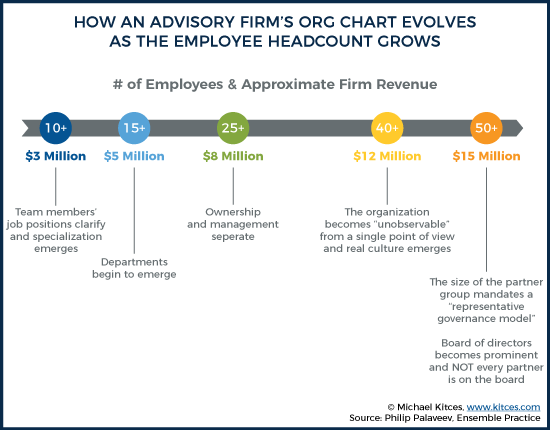

One of the fundamental challenges in growing an advisory firm beyond just the founder (and a handful of people to support him/her) is that a growing number of employees necessitates a greater amount of organizational infrastructure to support the people. From a human resources person (or eventually team) to the emergence of mid-level management, and the eventual erosion of decision-making efficiency as more partners/owners are introduced… it’s not uncommon for advisory firms that are growing to suddenly lose momentum, precisely because their growth causes the current structure of their organizational chart to break down and lose its effectiveness.

In this guest post, practice management guru Philip Palaveev of The Ensemble Practice shares his perspective on how, exactly, an advisory firm’s “org chart” should change an evolve as the business grows. Because the reality is that when it comes to advisory firms, one size does not fit all when it comes to the proper structure of an org chart… not just because different advisory firms have a different focus and style, but because the needs of the organization itself will vary depending on whether there are 10, 25, or 50+ employees.

The starting point of a formal organizational chart structure typically emerges by the 10th employee, when it’s not enough to just have “people” who accomplish various roles in the business. Instead, formal (and increasingly specialized) roles begin to emerge in the firm, and the firm begins to set forth “positions” (that certain people may fill), rather than just gather together a growing number of people.

By 15+ employee, the growing specialization of positions within the firm begins to form departments, where multiple employees who share in a certain functional role within the firm (e.g., the investment team, the operations team, the advisory team) begin to form into groups, with multiple tiers of positions within the department that begin to create the future career tracks within the firm.

With continued growth past 25 employees, the advisory firm becomes so large and complex that there is typically a need for “full-time” management of the firm (e.g., a Chief Operating Officer), beyond just having founders who wear the hat of owner, leader, and advisor with clients. In fact, by 25+ employees, it’s not uncommon for ownership and management to begin to separate altogether, as not all partners necessarily can (or need to) have a role in the actual management of employees.

By the 40-employee headcount, the founders are often so distant from the end-employees and the meetings they’re having (both internally, and with clients), that true "culture" begins to emerge… a standardized set of norms that define what typically occurs in the firm even when no one is watching. Which in turn necessitates a growing focus on defining what the firm’s formal culture is… because it’s simply not possible for the founders to fully manage (or have much interaction at all) with everyone in the org chart.

And as advisory firms cross the 50-employee threshold, the size of the firm often mandates a “representative governance” model, as the firm often introduces enough owners/partners that it’s not even effective to give every partner a “seat at the table” anymore. Instead, a Board of Directors tends to form, and decisions are made by the Board and the firm’s management team, which the partners represented by certain members of the Board (but without the direct involvement of them all).

The key point, though, is simply to recognize that advisory firms tend to go through consistent challenges as their employee headcount and “org chart” reach a certain size and complexity thresholds… which, notably, are based not primarily on revenue, but actually on the number of people in the org chart (who must be connected to each other and managed). For which, hopefully, this article will serve as a helpful guide about how advisory firms who are “stuck” on how best to design (or restructure) their own Org Chart can move on to the next level.

All 15-year-olds believe they will never be anything like their parents. All 45-year-olds realize they are just like their mom or dad… and that’s not a bad thing at all.

As the advisory industry has grown and matured, it has repeated a pattern of change in organizational structure, with firms transforming themselves from small, family-like units into complex organizational structures involving more people and greater capabilities. While this maturation process often brings to an end the days of innocence — when the firm was “family”— its end result is a highly capable firm that can live on its own without relying on “mom and dad,” i.e., the founders.

The changes I am about to describe will make most entrepreneurs cringe: You will have departments and executives. You won’t feel like one family. You will have policies and procedures. You will no longer be able to socialize with your team. This is like telling a 15-year-old that one day she will have a job, bills, and a mortgage to worry about. She will do a bunch of things she currently loathes, and her own kids will think she is less cool than Sheldon Cooper, indeed. But these predictions are accurate, and this is a necessary conversation to have.

Why Do Advisory Firms Have to Change As They Grow?

A client of our consulting practice, the CEO and founder of a successful advisory firm, was telling me how every summer the entire team goes on his boat to celebrate their success. He even said that during the hiring process, they ask themselves whether the candidate would be fun to hang out with on the boat. He confessed to me that he is starting to get worried: “I might need a bigger boat!”

Organizations change when (and because) they grow. In order to grow, a firm needs to involve more people. With the arrival of more and more professionals, old structures become inadequate, and new forms of organization structure must emerge to unlock the ability of the firm to continue to function at a larger size. Familial structures can support 20 to 25 people at the most, before they lose their force of gravity and become problematic.

Four forces emerge with growth that necessitate the transformation from a family to a business:

More leaders are needed

When an organization employs 10 to 15 people, the leaders of the team — who are usually also founders — can easily get to know each and every person, and give them the attention they need. However, when the firm grows to 30 people or more, leaders find that they don’t have the time or energy to maintain so many personal relationships. Increasingly, employees don’t have access to the founder/CEO, but they still need direction and attention. More leaders are needed to provide that attention.

For new leaders to emerge, firms must move away from the “mom and dad” (founder) model, and find a new organizing principle. Stuart Silverman (my former partner and CEO of Fusion Advisor Network) grew quite frustrated with the line of employees waiting in front of his desk every morning when he arrived at the office. This was a clear sign that we had grown to a size where we needed to direct our team to multiple leaders, not just the founder.

Complexity demands structure

If you are building a sandcastle on the beach, you don’t need much of a plan or blueprint. If you are building a hotel on the beach, you better have both. The necessity to do more, reach more clients, and involve more people who serve a greater number of functions, requires every growing firm to spend more time planning and organizing. In fact, planning and organizing the firm’s resources and internal energy become vital functions unto themselves.

Outsiders challenge the status quo

The more a firm grows, the more likely it is to hire people who have had experience working in other, larger organizations. These “outsiders” will be suspicious of the existing family structure and its quirks and often-unwritten rules and search for “official” policies and procedures that are more familiar to them. We all need to realize that our little endearing family quirks are only endearing to us kids who grew up together. To others, these quirks are just plain weird at best and alienating at worst.

Growth is stunted

Firms change over time, and resisting these changes can stunt the growth of the organization and result in a company that is stuck at the same size. While this size may feel comfortable for the firm, adolescents must inevitably grow up, and so must the organization’s take on the responsibilities of “adulting.” A firm that doesn’t grow eventually loses its ability to attract and retain talent. Just think about how difficult it would be for a 35-year-old living with his parents to keep a girlfriend. Opportunity attracts people. It is the fuel that powers careers. Without growth, there is no opportunity. Without growth, there are no careers.

Positions, Not People

The very first change that happens in a firm is the transition from people to positions.

In the early days, the org chart is populated with names. Philip does a number of tasks that match his experience and skills. Brandon does what he can do and what he enjoys doing. Each person is treated as an individual, and jobs are designed around specific people. But when a firm reaches 10 or more employees, jobs are increasingly defined by the needs of the firm. Positions emerge.

Job descriptions, divisions of labor, and specialization are needed in order to create efficiency and productivity and organize the work in a growing firm. With growth, certain activities go from being part-time functions to occupying all the time and attention of one, or more, employees. Capacity becomes scarcer, especially at the highest level of training and compensation. Firms realize that they need to leverage the time of their top professionals. The only way to do that is to create support positions that absorb certain functions from the advisors.

The Emergence Of Departments

Specialization in advisory firms (or any business) eventually creates “centers of activity” that then transform into departments.

Departments are more than a bureaucratic structure to allow for the existence of the beloved middle management. They are an organizing principle that enables people in similar or connected jobs to collaborate closely, train together, communicate better, and be managed as a unit. There is a reason the offensive line of a football team spends a lot of time training together away from the punters and kickers: they must work through a different process, learn to communicate within their unit, and grow their own subculture.

Four departments typically emerge in advisory firms, typically by around $5 million in revenue:

Advisory/Wealth Management

This department comprises Practicing Partners (i.e., those who work with clients), Lead Advisors, Service Advisors, Associate Advisors, and Analysts. It may also include specialized financial planning positions, as well as other client-facing specialists such as tax experts and estate planning professionals. Business development and marketing functions are often part of this department, though they may necessitate a team of their own in larger firms. Leadership frequently consists of a committee of Partners rather than just one person, but it is also common to see positions such as Managing Director of Wealth Management Services, or my personal favorite, Chief Practice Officer (which is rare but should not be).

Investment

In more and more advisory firms, growth causes the separation of investment and advisory responsibilities, and a separate group of professionals takes over portfolio management. The Investment department is led by the Chief Investment Officer, and usually includes Portfolio Managers, Investment Analysts, and Traders. Other firms elect not to form an Investment department, and instead ask advisors to manage portfolios, a decision that forgoes efficiency in favor of customization and client proximity. In such cases, the Investment team may be a subgroup of the Operations department, and consist of Traders and dedicated “Investment Operations” staff.

Operations

The Operations department is led by the Chief Operations Officer (COO) and comprises Client Service Administrators, Performance Reporting Analysts, and other positions that work closely with client accounts, client data, and partners, such as custodians and broker-dealers. In some firms, this department may also include Traders. The compliance function is usually part of Operations, though it may also fall under Administration.

Administration

The Administrative department includes Administrative Assistants, Receptionists, Office Managers, Human Resource Managers, Technology Managers and staff, Accounting and Bookkeeping, and often Compliance as well. This department is usually combined with Operations into one group. It frequently reports to the COO, even in cases where Operations and Administration are separately defined. More rarely, firms will have a Chief Administrative Officer.

The emergence of departments is important because it ultimately unlocks two important processes in larger and growing advisory firms:

Specialized career paths

Departments, with multiple tiers of specialized roles, outline the future track for team members of every function. Advisory careers separate from careers in operations and investment management. These specialized career paths tend to be clearer, and more systematic.

Middle management and distributed leadership

Departments are often the answer to the line in front of the CEO’s office. They allow each team and group of employees to have a leader and a manager who can provide them with the attention and direction they need.

Departments also create hierarchy and bring a level of centralization to decision-making, which often forces owners to reconsider their roles.

Separation of Ownership and Management

I often tell clients that if it is a road trip, we can all take turns driving the car, but when the car turns into a bus, we need to hire a professional. And sometimes that bus turns into a train or an airplane. That’s when we really need the professionals.

When advisory firms grow larger than 30 employees, the job of coordinating and managing the activities of team members requires so much time and attention that the company is well advised to assign dedicated managers to the task.

A dedicated manager is not synonymous with an outside manager. This is a crucial point, so let me repeat: the decision to assign dedicated managers does not necessitate hiring outside the firm. Dedicated managers are simply professionals who leave many of their client responsibilities behind to focus (solely and fully) on managing the firm.

On the other hand, there is nothing wrong with outside managers. In fact, outside managers can bring badly needed experience and expertise into the firm. Some of the best CEOs in the industry were hired externally. Take, for example, Bob Oros of HighTower, and George Stapleton of RegentAtlantic. Many equally great CEOs grew their careers within their firms but were not founders: Michael Nathanson of The Colony Group, Ken Hart of Cornerstone Advisors, Anthony Cecchini of JMG Financial Group, and Eric Kittner of Moneta Group (who is technically chairman of the board). Finally, many founders transitioned themselves into the CEO role: Armond Dinverno of BDF, Tim Chase of WMS Partners, and Dale Yahnke of Dowling & Yahnke.

The key point is that, at a certain size, a committee of Partners can no longer manage the firm. Decisions become too numerous, time-consuming, and complicated for an “amateur group.” The required level of needed management skills goes beyond the skills held by most Practicing Partners, and the time commitment is often too much for most to accommodate. Most importantly, committees tend to function by consensus, and consensus is not a good management process. It is too slow, too laborious, and too vulnerable to what is known as the “Abilene Paradox” – a frequent situation where the consensus option isn’t actually anyone’s preferred option!

Contrary to popular lore, the first “professional manager” is not a CEO, but a COO. The Chief Operating Officer often comes from the outside, to bring in processes and systems that can transform the firm. The presence of the COO often acts as a catalyst in encouraging other executive positions to emerge.

At this point, Partners often ask themselves what partnership even means: “If I am not involved in making decisions, am I just a glorified employee/investor?” The answer to this question, which is admittedly difficult to hear, is largely, “Yes!”

Partners show “real” ownership by acting as leaders and striving to be stewards of the business. They set an example for others to follow. While they can coach, manage, and train those who work with them, they don’t need to be involved in buying CRM systems or designing incentive compensation. I have had to learn this myself. I own a boxing gym, but that does not mean I have to fight every boxer with membership. After the dust settles, many Partners are actually relieved that they do not have to be involved in every management decision.

Captains Drink Alone

My father once told me that the captain of the ship drinks alone in his cabin. In other words, captains cannot freely socialize with the crew because it is their responsibility to be leaders. The same principle applies to advisory firms as they grow.

In the early days, everyone goes to happy hour together, and the firm’s holiday party is often held at the founder’s house. Later on, the founder who is now CEO learns that her presence changes the party dramatically. She can no longer “take off the blazer” and just be one of the gang.

I myself was friends with the first employee I ever hired at The Ensemble Practice. Then I had to fire him. The friendship did not help at all. In fact, I still wonder whether he would have heard my feedback better and more clearly had we not been friends. Perhaps he would have corrected the issues that ended his career at the firm had he not heard the comments coming from a friend. Perhaps I would have provided better feedback and coaching had I been more removed.

Many CEOs and executives learn through bitter experience that, after a few drinks, they are still the CEO. The standards governing their behavior do not change just because it is a party. A tipsy employee who says something stupid at a party is an embarrassing episode. An inebriated CEO who says something stupid, on the other hand, is a cultural issue and perhaps worse.

Many founders do not like this change, as it means losing a lot of their social life. After all, founders spend so much of their time working in the business, that they often lose other social connections. While giving up the ability to socialize with the team hurts, it may be healthy… and perhaps necessary for the future growth and success of the business.

The Real Culture (Beyond The Founders)

Organizational culture is often defined as what happens when no one is watching. Based on this definition, the real culture of a firm only emerges when it grows to a size where there are “dark corners” that the founders don’t see.

The culture of a small firm is not so much a culture, as a network of relationships. It is the hub-and-spoke model of the founder or founders having relationships with each employee, and being able to directly observe and manage their behavior.

When the firm grows to 40 employees or more in size, there are too many spokes and the model must change. Behavior occurs in a different context and is not as directly observed. This is when people find other leaders to follow, either by design or happenstance. At this point, what happens in the Investment department may be more of a function of the leadership of the CIO, than the CEO. This is when entry-level Analysts absorb their lessons from the Associate Advisors ahead of them, rather than the founders. This is when real culture comes into being.

Culture is like a nose: everyone has one, you don’t see it most of the time, but it is always there and you may or may not like it when you see it in the mirror. Culture follows the example set by leaders, but founders often misunderstand the example they themselves set.

Developing People To Fill In The Org Chart’s Leadership

One of the biggest transformations that occurs within an advisory firm is also one of its biggest weaknesses. In order to grow and retain its culture, a firm needs to prioritize the development of people.

It is impossible for a large firm to exclusively rely on hiring from the outside. As a firm grows, it needs more leaders. The best way (but not the only way) to develop those leaders is from the inside. Professionals who grow up in the firm will honor and follow its traditions and best represent its culture.

The importance of developing people means that Partners who are capable of mentoring and coaching become just as valuable as Partners who can attract many new clients. Firm leadership should, therefore, spend a lot of time developing the most promising future Partners. Unfortunately, not enough firms make this transformation. The result is a top-heavy firm, with a very underdeveloped cadre of next-generation (or G2) leaders.

The Rise Of Representative Governance

Finally, as firms grow, some reach a size where the rights of the owners are exercised through a representative model, rather than a “direct democracy.” Ownership and governance separate. Once a firm has more than 10 owners, it is time to start looking at forms of decision-making that are more decisive than a Partner meeting.

At this size, many firms start forming a board of directors to represent owners, that does not include every single owner. Owners rely on their elected representatives to exercise their vote and their rights. Being a Partner becomes an abstraction in the sense that it no longer directly connects to managing or even owning. Instead, being a Partner becomes a chance to lead by example, and a sign of professional achievement.

The advisory industry is changing as we speak. Today there are well over 700 firms with a billion or more in assets under management. A cadre of another 5,000 firms has between $300 million and a billion.

As firms grow, their transformations are shaking the status quo and challenging leaders to keep up with the changes they themselves set in motion. And while these changes are natural, necessary, and for the best, they are not easy to make. But make them we must. So I will leave you with some words of encouragement that my dad often gives to me: if it were easy, everyone would be doing it.

Leave a Reply