Executive Summary

It’s long been a tenet of taxation that when a group of individuals come together for a “joint venture”, the taxation of their collective business should simply be done by taxing each individual on their respective share of the business. Over the years, this has been formalized into the structure of “pass-through” business entities, from partnerships to LLCs to S corporations (and of course, the sole proprietor themselves)… all of which simply subjected the business’s income to the tax rates of their individual shareholders.

Until the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, which for the first time has introduced a so-called “Qualified Business Income” (QBI) deduction for pass-through entities that will effectively permit pass-through businesses to be taxed on only 80% of their income. To some extent, the introduction of this new QBI deduction was necessary to keep pass-through business tax rates reasonably in line with corporate tax rates (which were also reduced to 21% under TCJA) when stacked on top of qualified dividend or long-term capital gains tax rates. Yet at the same time, the new QBI deduction also introduces a substantial tax planning opportunity… and some complexity, too.

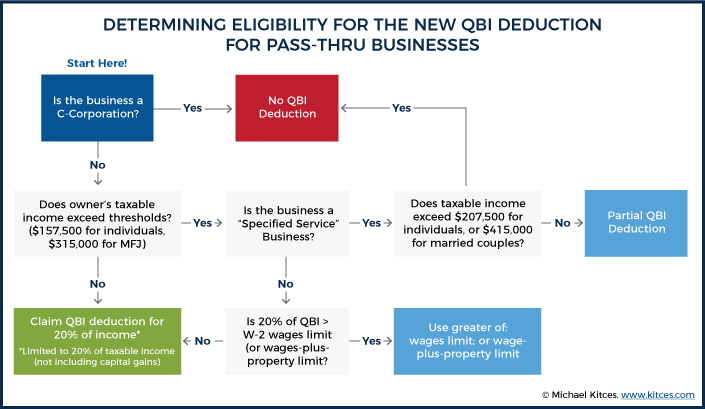

The core of the qualified pass-through business income deduction is that shareholders will simply be permitted to deduct 20% of the business income against itself, which will be claimed as a below-the-line (but not itemized) deduction for tax purposes. However, to prevent abuse – especially at higher income levels – the new QBI rules do not permit the deduction for high-income “Specified Service” businesses (including lawyers, accountants, doctors, consultants, and financial advisors), and high-income individuals may also have their QBI deduction limited if they do not employ a substantial number of people relative to the size of the business (under a new “W-2 wages” limit), or invest into a substantial amount of property (under the “wages-and-property” limit).

The end result of these rules is that small businesses should have relative ease claiming at least a modest new QBI deduction, which is available even if they’re simply a sole proprietor (i.e., it’s not necessary to literally create a pass-through business entity like a partnership, LLC, or S corporation). And large highly scaled businesses may enjoy an even greater deduction. However, businesses that rely primarily on the efforts of their owners – whether overtly as Specified Service businesses, or simply those with a limited amount of employee or capital investments – may still struggle to take advantage of the new QBI rules, especially those over the new income thresholds of $157,500 for individuals, and $315,000 for married couples!

Why Pass-Through Businesses “Need” Special Treatment

In the early days of business formation, two (or more) individuals could come together in a joint venture that was dubbed a “partnership”. Each partner would be responsible for their proportionate share of business income and expenses, and be responsible for paying taxes on the income. By contrast, in select cases, business owners decided that they wanted to establish a standalone and discrete entity from themselves, for which they would form a Corporation that was responsible for determining (and reporting on, and paying taxes on) its own income, for which the business owners would then report their own taxable events based on what they did with those corporate shares (e.g., received a dividend, sold for a capital gain, etc.).

While the exact nature of business entities has evolved over time – to the point where today, some corporations share some of the properties of pass-throughs (e.g., S corporations), and other partnership entities are more corporate-like (e.g., the separate and limited business liability of an LLC) – the underlying framework remains in place: that the income of partnership-style businesses is taxed directly to the owner (i.e., the income is “passed through” to them), while corporate-style businesses report and pay taxes on their own income (and the shareholders then have their own tax consequences for how they earn income from, or generate appreciation on, their shares).

An important consequence of this structure is that in essence, pass-through businesses are taxed once (where each owner reports their respective share of income), while corporates are taxed twice (once at the corporate level, and again as a dividend or capital gain in the hands of the shareholder). Which means that the relative tax burden of two tiers of corporate taxation (as corporate tax rates plus dividend/capital gains rates) versus a single tier of taxation for pass-throughs (as the individual tax rate) has a significant impact on the choice of a business entity type.

For the past 30+ years, pass-through businesses have generally been taxed at lower rates than corporations, at least once both tiers of taxation are considered. As a result, over the past 30 years, the number of (predominantly small business) pass-throughs has tripled, and pass-through businesses earn the majority of the business income (and employ the majority of the private sector workforce).

However, a key aspect of this dynamic is that it means when one business type changes tax rates, it’s important to consider not only the ramifications on that business type, but also on the relative difference between the various entity choices. Through 2017, the top corporate tax rate was 35%, and the top dividend and capital gains tax rate was 23.8% (including the 3.8% Medicare surtax), for a total of 58.8% (although technically corporate taxes paid reduce subsequent dividend/capital gains taxation). By contrast, the top individual rate was “only” 39.6%.

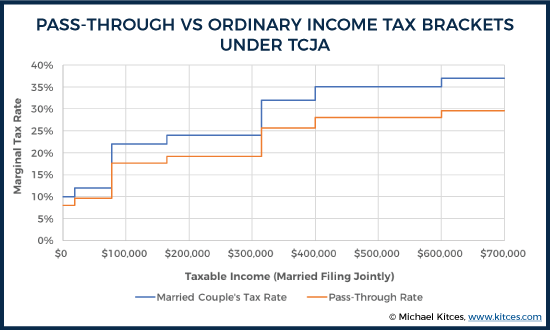

With the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, though, the top corporate tax rate was reduced from 35% to just 21%, in an effort to make the marginal US corporate tax rates more competitive with other countries around the world (particularly to better incentive US businesses to repatriate overseas profits back to the US). Yet doing so brought the combined top corporate tax rate down to “just” 21% + 23.8% = 44.8%, which is relatively close to the top individual rate, and would have substantially eroded the tax preferences otherwise associated with pass-through businesses.

Accordingly, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act also provided a new incentive to pass-through businesses, known as the new “Qualified Business Income” deduction, that allows pass-through businesses to deduct up to 20% of their own net income against that income, effectively making them taxed on only 80 cents of each dollar they earn. This reduces the top marginal tax rate on pass-through business entities from a new top tax rate of 37%, down to a reduced rate of 37% x 80% = 29.6%, better preserving the “gap” between pass-through and corporate taxation, for what are still predominantly a wide swath of small-to-mid-sized business owners who employ the majority of Americans.

Rules For Deducting Qualified Pass-Through Business Income

Notably, despite its popular label as a “pass-through” business deduction, the new rules actually do not limit it to “just” standalone pass-through business entities. According to the Congressional Conference Committee notes, and the new IRC Section 199A(c)(3)(ii), the new deduction is really available to any business entity that is not a C corporation – which includes S corporations, partnerships, and LLC entities, but also sole proprietors who are simply paid directly as independent contractors, as long as the business’ income is included in the individual’s income for tax purposes. In other words, in practice, it’s less of a “pass-through business” deduction, and more of a “not-a-C-corporation” deduction.

To actually qualify, though, the pass-through “business” must have “Qualified Business Income” (QBI), which is defined as the net income of the pass-through businesses after all business deductions have been claimed. QBI is calculated separately for each eligible business, such that the partner/owner’s respective share of income and expenses can be calculated for each business. Although for pass-through businesses where there is often a mixture of income paid to work “in” the business, versus income for ownership “of” the business, the rules explicitly exclude any salaries to S corporation owners, and guaranteed payments allocated to partners in a partnership (or members of an LLC), from being considered as QBI income. In addition, the rules broadly prohibit “reasonable compensation” as being classified as QBI; in the case of an S corporation, this means it really will be necessary to pay reasonable compensation (salary) to the owner, although it’s not clear whether/how this will be applied to partnerships, LLCs, or sole proprietorships that don’t have a salary (where it would be harder to track and classify how much of the business income is “reasonable compensation” to the owner for services rendered in the first place).

It’s also important to note that income must actually be connected to the conduct of a trade or business (within the United States) to actually qualify; as a result, only “business” income is eligible, and only domestic business activities are eligible. In addition, the rules under IRC Section 199A(c)(3)(B) explicitly stipulate that capital gains (both long-term and short-term), dividends, and investment interest income, are not eligible for QBI treatment (nor is income from a non-qualified annuity), which prevents investors from shifting their investment income into a partnership or LLC just to try to convert it into qualified business income eligible for the deduction. Notably, though, the rules do permit income from REITs to be eligible for the QBI deduction (to the extent that their distributions are normal REIT income and not attributable to capital gains or qualified dividends).

Example 1. Joseph and Rachel are married and earn $220,000/year, which includes $90,000 in wages from Joseph’s job managing a theater, and $130,000 of net income from Rachel’s clothing store (which is simply a sole proprietorship business reported on her Schedule C). In addition, the couple has a $150,000 portfolio, that produced $3,000 of qualified dividends and $2,000 of REIT income in the past year. The couple’s total income is $225,000, of which $132,000 (including Rachel’s business income and the REIT income) are “Qualified Business Income”.

In 2018, the couple will be eligible for a $24,000 standard deduction, reducing their $225,000 of income down to only $201,000. In addition, they will receive a $26,400 QBI deduction, further reducing their income to $174,600. Given that the couple will be in the 24% tax bracket, this means that the QBI deduction of $26,400 produced a $6,336 tax savings.

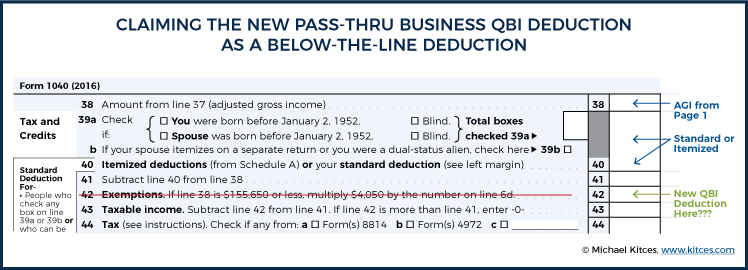

Notably, the QBI deduction is not an above-the-line deduction that reduces Adjusted Gross Income. Instead, it is a “below-the-line” deduction, albeit not an itemized deduction. Which means the QBI deduction can be claimed (as a below-the-line deduction) regardless of whether the taxpayer itemizes, or claims the standard deduction. In essence, the QBI deduction will replace what was previously the below-the-line deduction for personal exemptions (which also went alongside either the standard deduction or itemized deductions).

In addition, the deduction for qualified pass-through business income is also limited to 20% of the household’s taxable income (i.e., income after all deductions, but before the QBI deduction itself). And this determination is based on the business owner’s personal tax return, even though the QBI deduction itself is calculated based on the business’s income. The end result, though, is that if the household’s income after deductions is lower than the net income from the business in the first place, the 20%-of-taxable-income limit will reduce the QBI deduction below “just” claiming 20% of business income. (And for this determination, the calculation is based on 20% of just ordinary income after deductions, and not capital gains income!)

Example 2. Ross and Emily are joint owners of a very successful curio shop, that last year generated $140,000 of net income. In addition, the couple earned about $3,000 of dividend income and had a $5,000 capital gain from the sale of some stocks (that they used to procure an especially rare and old wardrobe from London for the shop). The couple’s Qualified Business Income is $140,000, and their total Adjusted Gross Income is $148,000.

Ross and Emily are eligible for a $24,000 standard deduction, which results in a “tentative” taxable income of $124,000 (or $119,000 not including capital gains), and are eligible for a QBI deduction for the lesser of either: 20% of their QBI ($28,000), or 20% of their taxable income not including capital gains (which would be $119,000 x 20% = $23,800). Thus, even though their “tentative” QBI deduction would have been $28,000, the limitation to only 20%-of-tentative-taxable-income reduces their QBI deduction to just $23,800. Which means their final taxable income is $124,000 - $23,800 = $100,200, to which the 2018 tax tables would be applied.

It’s important to note, as illustrated in the above example, that anytime “most” of a taxpayer’s income is their (Qualified) Business Income, that the application of the standard deduction (or itemized deductions) against that income will typically mean the 20%-of-QBI deduction is reduced to 20% of their (tentative) taxable income instead. In addition, because the ordering rules for claiming deductions apply them against ordinary income first, the inclusion of additional capital gains won’t necessarily preserve the QBI deduction. (As illustrated above, the couple’s total income included $5,000 of capital gains and $143,000 of other income, but the entire $24,000 standard deduction was applied only against the $143,000 of other income, reducing it to $119,000, and the 20% limitation was then applied based on this reduced amount.)

Ironically, though, this means that taxpayers whose QBI deduction is limited by the 20%-of-taxable-income threshold will effectively be able to increase their QBI deduction by creating other non-business income. As any increase in income at that point – Qualified Business Income or otherwise – can lift this limit and allow the entire 20%-of-QBI deduction to be claimed.

Example 2b. Continuing the prior example, assume that Ross and Emily also complete a $25,000 Roth conversion this year. The Roth conversion increases their Adjusted Gross Income to $173,000, lifts their tentative taxable income to $149,000, and increases their non-capital-gains taxable income to $144,000. As a result, their QBI deduction will now be the lesser of either 20% of their QBI ($28,000), or 20% of their non-capital-gains taxable income ($28,800). Which means the couple will now get their entire QBI deduction, resulting in a final taxable income of $149,000 - $28,000 = $121,000. Or viewed another way, the addition of $25,000 of Roth conversion income “only” increased their taxable income by $20,800, because the Roth conversion allowed them to claim an additional $4,200 of the QBI deduction!

For those who are subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), the QBI deduction is equally available for AMT purposes, and is still calculated (including the 20%-of-taxable-income limit) based on “regular” taxable income (without respect to any AMT adjustments or preference items).

High-Income Limitations On The QBI Deduction For Pass-Through Businesses

Beyond the limitation that the QBI deduction applies only to “pass-through” business income (and not other types of income), and is capped at 20% of taxable income, two other limits can also apply, for those who are “high-income” individuals.

In this context, “high income” means individuals with taxable income over $157,500, and married couples (filing jointly) over $315,000 of taxable income. These thresholds correspond to the top of the new 24% bracket, and the onset of the new 32% bracket.

For those who are over these income thresholds, the tentative amount of the QBI deduction may be reduced by two further limitations (in addition to the 20%-of-taxable-income limitation):

- The “Specified Services” phaseout

- The Wages (and/or Wages + Property) limit

Specified Service Business Limits For The Pass-Through Business Deduction

In order to receive the Qualified Business Income deduction, IRC Section 199A requires the income to come from a “qualified” trade or business, which is defined as any business other than one performing services as an employee… or any “specified service” trade or business. Which means anyone who is ultimately still an employee, or whose business is engaged in any of the “specified services”, will not be eligible for the QBI deduction.

In this context, “specified services” are explicitly defined under IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A), and include:

“…any trade or business involved the performance of services in the fields of health, law, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees…” or

“…Which involves the performance of services that consist of investing and investment management, trading, or dealing in securities, partnership interests, or commodities...”

The first section effectively excludes most professional services businesses, while the section precludes hedge fund and other investment managers (including investment advisers) from being eligible for the QBI deduction.

Notably, IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) normally also includes “engineers” and “architects” as specified services as well, but the final version of TCJA explicitly excluded those professions, under the reasoning that ultimately they produce physical deliverables (architectural or engineering plans and blueprints) and therefore aren’t solely just “service” business.

Fortunately, though, the specified service limitation doesn’t always apply. Instead, this limitation is phased in once taxable income exceeds $157,500 (for individuals, or $315,000 for married couples filing jointly). The phase-in range is $50,000 (for individuals, or $100,000 for married couples). Which effectively means that once taxable income exceeds $207,500 or $415,000, respectively, the QBI deduction is phased all the way down to zero for a specified service business.

Example 3. Matthew is a 50% partner in a law firm that generated $500,000 in net profits last year (of which Matthew received his $250,000 share). In addition, Matthew’s wife Jennifer is an experienced engineer who makes a $100,000 salary. And the couple has a portfolio that cumulatively generated about $40,000 of interest and dividends in the past year. As a result, their combined Adjusted Gross Income is $390,000, and since they don’t own a home (no mortgage interest deduction) and their other deductions are limited, they simply claim the $24,000 Standard Deduction, which reduces their tentative taxable income to $366,000.

Matthew would normally be eligible for a $50,000 QBI deduction (which is 20% of his $250,000 share of business income), but as a lawyer, his law firm business income is “Specified Service” income. And because the couple’s tentative taxable income is $366,000, they are 51% of the way through the Specified Service business phaseout zone (being $51,000 out of $100,000 over the $315,000 threshold for married couples). As a result, they only keep 49%, or $24,500, of their QBI deduction, which ultimately reduces their taxable income to $366,000 - $24,500 = $341,500.

It’s crucial to recognize that the income phase-out for a Specified Service business is based on the individual’s personal tax return, and not just based on the amount of business income. As shown in the example above, Matthew’s business income was only $250,000, which was below the $315,000 threshold. However, the couple’s combined income was $390,000 (reduced to $366,000 after the standard deduction), which was enough to partially phase out the QBI deduction for Matthew’s specified service income.

In fact, any income which contributes to taxable income can cause Specified Service income to phase out. Not only does it not need to just be business income over the threshold, but it doesn’t even need to be wages or other active income. Nor does it even need to be ordinary income (like a Roth conversion or portfolio income); even a sizable long-term capital gain can further phase out the QBI deduction for Specified Service businesses!

Example 3b. Continuing the prior example, imagine that the couple also takes a $50,000 long-term capital gain in the same tax year. Long-term capital gains are eligible for preferential tax rates; however, they are still “income” for tax purposes, and increase both Adjusted Gross Income and taxable income. As a result, the couple’s tentative taxable income would be increase to $416,000 (of which $366,000 will be taxed at ordinary income rates, and $50,000 will be taxed at long-term capital gains rates). Since $416,000 is above the threshold for the full phaseout of the QBI deduction, the capital gain will completely phase out the QBI deduction for the couple.

Which means even though the long-term capital gain will be eligible for 15% tax rates (plus the 3.8% Medicare surtax at their income), the loss of a $24,500 deduction (at their 33% ordinary income tax bracket) will add another $8,085 of taxes for this $50,000 long-term capital gain, which means their “true” marginal capital gains tax rate – thanks to the phaseout of the QBI deduction – will actually be 15% + 3.8% + ($8,085 / $50,000) = 34.97%!

On the plus side, the Specified Service business limitation applies only to “specified” service business income, and not just any/all service businesses. And the QBI deduction itself is calculated separately for each business, which means someone who owns multiple businesses – where some provide “specified” services and others that do not – may find that some QBI deductions are phased out, while others are not!

Example 4. Charlie is a financial advisor who owns several other businesses as well. His advisory business is an S corporation, which provides him a $150,000 salary, plus an $80,000 income distribution. In addition, he also generates $85,000 of net income from a real estate business (3 small rental properties), along with $25,000 of income from a landscaping business he seeded for his best friend, and his portfolio produced $60,000 of interest and dividend income (of which $15,000 was from REITs).

Charlie’s total income is $150,000 + $80,000 + $85,000 + $25,000 + $60,000 = $400,000, which as an individual taxpayer is more than enough to exceed the full phaseout threshold for the QBI deduction. However, only his $80,000 profit distribution is actually specified service income; the landscaping business is a “service” business, but not a specified service business, and his real estate business and REIT income also remain eligible for the QBI deduction.

As a result, Charlie’s potential QBI deductions would be 20% of his advisory business income ($16,000), plus 20% of his real estate income ($17,000), plus 20% of his landscaping business income ($5,000), plus 20% of his REIT income ($3,000). The $16,000 QBI deduction for the advisory business is phased out due to Charlie’s income and the Specified Service business limits, but the other $17,000 + $5,000 + $3,000 = $25,000 of QBI deductions remain (assuming they can otherwise satisfy the wages or wage-and-property tests discussed below). Which means Charlie’s taxable income will ultimately be $400,000 - $12,000 (Standard Deduction, assuming he does not itemized) - $25,000 = $363,000.

On the other hand, it’s notable that because the Specified Service business limit is based on the taxpayer’s own individual tax return, if Charlie had a partner in his advisory business who was married but only earning income from the advisory business, the partner would still receive the full QBI deduction (as the total salary-plus-distributions income from the S corporation would not exceed the married couple threshold for a Specified Service business). Stated more simply, because the Specified Service business limit is applied based on each individual’s own tax return, it’s entirely possible that some (higher income or senior/founding partners) may be impacted by the limit, while other (lower-income and/or junior/minority partners) still receive the full deduction!

W-2 Wages And Property Limits For The Pass-Through Business Income Deduction

The second limitation that may potentially apply to the QBI deduction is a wage (and property) limit.

Specifically, the IRC Section 199A rules stipulate that the QBI deduction is actually the lesser of either 20% of QBI, or the greater of either:

- 50% of the W-2 wages of the business; or

- The sum of 25% of W-2 wages plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of all “qualified property” in the business

In this context, qualified property is defined as any tangible property for which depreciation deductions are allowed under IRC Section 167, that was held by and used in the business, and hasn’t already reached the end of the depreciable period. This could potentially include anything from machinery and equipment, to real estate holdings, that are still being depreciated. (Although controversially, it might not include Section 179-expensed property, which is depreciable property but is never actually depreciated; future Treasury Regulations will hopefully provide additional guidance on this issue.) The “unadjusted basis” of the qualified property is its value immediately after purchase and before actual depreciation; in other words, the “original” basis of the property.

Under the original House GOP version of the QBI deduction, this limitation would have only been a 50%-of-W-2 wages limitation, which would have substantively curtailed the QBI deduction for many highly-capital-intensive businesses, from manufacturing to real estate. With the option of either 50% of W-2 wages, or 25% of wages plus 2.5% of property basis, far more capital-intensive businesses will be eligible.

Example 5. Eric is a real estate investor whose business both purchases and rents properties, and is responsible for property management. In total, the business holds nearly $20,000,000 worth of residential real estate that he has purchased over the past 8 years (combined original purchase prices of $16,000,000), generates net income of approximately $1,000,000, and has 3 people on the payroll earning a total of $230,000.

Given these dynamics, Eric’s QBI deduction “should” be 20% of his $1,000,000 of net income (which would be $200,000), but may be limited by the wages and property caps. The wage limit – which is 50% of W-2 wages – would cap his QBI deduction at “just” 50% x $230,000 = $115,000. However, the wage-and-property limit caps his QBI deduction at 25% x $230,000 + 2.5% x $16M = $457,500.

Thus, thanks to the sizable amount of real estate he owns, Eric’s wage-and-property limit is the greater of either $115,000 or $457,500 (which means the property limit applies). And since the QBI deduction is ultimately the lesser of 20% of QBI or the wage-and-property limit, the lesser of $200,000 or $457,500 is $200,000. Which means Eric actually does receive his full QBI deduction.

Notably, in the example above, the 50%-of-wages limit alone would have capped the QBI deduction (at just $115,000). However, the second wages-and-property limit option alleviated any pressure from this limit, allowing the full QBI deduction to still be claimed.

In fact, given that most businesses are generating income from either a substantive amount of property (whether real estate or machinery/equipment), or a substantive number of employees, suggests that this limit will typically still be easily surpassed by most. The greatest limitation may actually just be that the 50%-of-wages limit counts only the actual wages of employees. Which means businesses that use a lot of independent contractors, such as certain labor-intensive businesses like landscaping or certain types of construction and contracting, may be severely curtailed by the W-2 wages limit because they don’t pay much of any actual wages (and not have much property for the 2.5%-of-property limit).

However, as noted earlier, this wages (or wages-and-property) limit still only applies to high-income individuals, which again is based on each business owner’s personal tax return and the $157,500 and $315,000 thresholds. To the extent they are subject to the limitation, the otherwise-allowable QBI deduction is then reduced down to the new limited amount.

Example 6. Jason is single and runs a contracting business that last year generated $200,000 of net income. The gross revenue of the business was almost $700,000, but reduced by $70,000 of wages he pays to his project manager, about $30,000 of office and administrative expenses, and about $360,000 paid out to various (independent) subtractors on his projects.

His QBI deduction would normally be 20% x $200,000 = $40,000. However, Jason will potentially be limited to a deduction of just 50% of W-2 wages, which is “only” $35,000, or a $5,000 reduction in the QBI deduction.

Jason’s tentative taxable income (after claiming the Standard Deduction) will be $200,000 - $12,000 = $188,000, which puts him 61% of the way through the $50,000 phaseout (that started at $157,500 of taxable income as an individual). As a result, 61% of the $5,000 W-2 wages reduction in the QBI deduction will apply to him, which reduces his QBI deduction by 61% x $5,000 = $3,050, making his final QBI deduction only $36,950.

Had Jason’s taxable income exceeded $207,500, his QBI deduction would have been reduced by 100% of the $5,000 difference, bringing his QBI deduction down to $35,000.

Similar to the Specified Service business limit, because the limitation is applied based on the taxpayer’s own income on his/her personal tax return, it’s possible that some partners/members/shareholders of a pass-through business will be subject to the wages (or wages-and-property) limitation, even as others are not and receive the full QBI deduction. (Although each does the calculation for their pro-rata share of W-2 wages and property when calculating the limits, and applies the limit based on whether his/her own taxable income is over the threshold.)

On the other hand, for high-income partnerships or LLCs (or sole proprietors) with few or no employees, it’s possible that the imposition of the W-2 wages limit may reduce the business’ QBI deduction all the way down to $0, since only S corporations can actually pay their owners an actual W-2 wage salary in the first place!

Ultimately, the new Qualified Pass-Through Business Income rules is the biggest change in the taxation of small businesses in decades. For which a number of ambiguities remain, from whether/how “reasonable compensation” rules will apply not only to S corporations but also partnerships, LLCs, and even sole proprietorships, to further clarification on what other service businesses might be deemed “Specified Service” businesses because “the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees”, to the proper application of the wage (or wage-and-property) limits to businesses with no employees (which therefore may have no wages at all!?).

Nonetheless, given the substantial potential for tax savings, expect more and more QBI planning strategies to emerge in the coming years!

So what do you think? Have you had conversations with your clients about QBI planning strategies after the TCJA of 2017? What are your favorite strategies for QBI planning going forward? How do you plan to communicate these strategies to clients? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!