Executive Summary

As financial advisors increasingly adopt ETFs, the wholesale shift from actively managed mutual funds to passive investment vehicles is driving more inflows to ETF providers like Vanguard and Blackrock and State Street and than all other mutual fund families combined… and leading mutual fund companies into a mad scramble to figure out what they have to do to once again appeal to financial advisors.

Yet the reality is that, with the rise of the internet, the fundamental role of the financial advisor themselves is changing. In a world where consumers can purchase virtually any publicly traded investment online themselves, financial advisors are compelled to add value above and beyond “just” bringing third-party mutual fund managers to the table. In fact, an increasing number of financial advisors appear to be “coping” by eliminating third-party managers, and instead becoming the investment portfolio managers themselves.

In this context, the rise of ETFs is not so much about a shift from active to passive, but simply a recognition that when financial advisors build investment portfolios, we prefer to do it using ETFs as our “building blocks”, rather than individual stocks and bonds. Although in point of fact, a recent FPA Trends in Investing Survey revealed that advisors are increasingly building portfolios with ETFs, and stocks, and bonds, and even private equity funds – anything except third-party mutual funds. Which just helps to show how the shift from active to passive is really just a mirage; what’s really occurring is a process where financial advisors are remaining active, but disintermediating mutual fund managers and going hands-on to actively build the portfolio themselves, whether as an independent RIA, or under a Rep-As-PM arrangement in a broker-dealer.

Of course, the caveat is that just as many mutual fund managers have struggled in an increasingly competitive market for alpha to outperform their benchmarks, there’s no indication that individual financial advisors are any better at the process. Which means ultimately, the financial-advisor-as-investment-manager shift itself may be short-lived, as advisors further shift to providing financial planning value outside of the portfolio altogether. But until financial advisors get to the point that the majority of us truly view our value-add as going beyond the investment portfolio – where a bona fide shift to passive investing may gain further traction – the ongoing rise of ETFs will remain less about a shift to passive itself, and more about how financial advisors are defending their own fees by squeezing out the costs of the investment products they use for client portfolios!

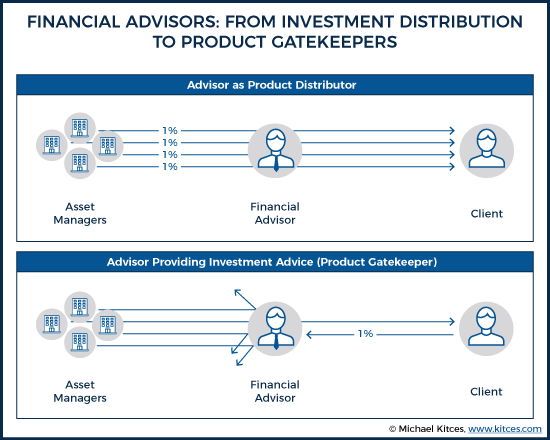

Financial Advisors: From Investment Distributors To Product Gatekeepers

Historically, most “financial advisors” functioned as investment salespeople, responsible for selling and distributing investment products, for which they were paid a commission from the product manufacturer. From the early days of wirehouses selling proprietary products, to the rise of independent broker-dealers selling third-party products, the reality was that advisors were most successful by finding the most profitable products to sell – through some combination of those that paid well for sales (i.e., high commissions), and/or were good enough to sell themselves in volume (i.e., high quality). And for most consumers, there was no way to access those investment products, short of working with a financial advisor, as relatively few asset managers had direct-to-consumer distribution channels.

However, with the rise of the internet, consumers have been increasingly able to access virtually any investment product they want, either directly from the asset manager or product manufacturer, or through a self-directed brokerage account. This shift has led to both the rise of “no-load” investment products – as if there’s no “advisor” salesperson to be paid, there’s generally no need to have a commission load in the first place – and a rising pressure on investment commissions themselves, as consumers increasingly ask “what’s the value of paying a ‘financial advisor’ to provide the same products I could buy directly without the cost?”

For financial advisors, this has created substantial pressure to provide more value to justify the 1% 12b-1 compensation layer they are often receiving (especially when it was typically stacked on top of the underlying ~1% operating and management fees of the mutual fund itself), shifting the traditional 1% 12b-1 commission trail for product sales into a 1% advisory fee for ongoing investment advice. Yet the shift from product distribution to advice to justify a 1% AUM fee means the role of the financial advisor themselves is shifting from being a distributor of investment products (for the product manufacturer), into a gatekeeper on those very investment products (on behalf of the client to whom they’re providing advice).

The end result of this shift is that financial advisors have newfound incentives to limit investment funds and control investment costs for clients, in a way that never existed in the past. In fact, one of the primary ways that the financial advisor can justify their value and 1% fee, is to squeeze out costs from the underlying investment portfolio. In other words, one of the easiest ways for a financial advisor to justify their 1% AUM fee, is to save the client 1% of underlying investment costs!

How Financial Advisors Are Disintermediating Mutual Funds

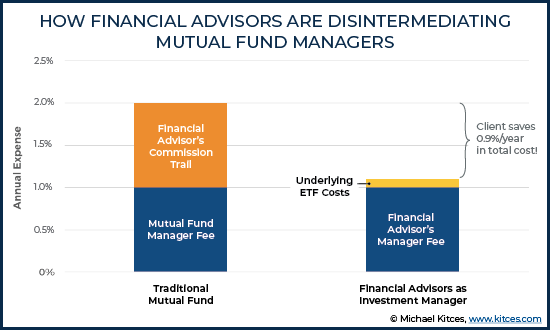

Notably, the shift of the financial advisor from investment product distribution to investment advice means advisors have not only become gatekeepers that block out high-cost funds in lieu of lower-cost alternatives, but also incentivizes the financial advisor to actually be the investment manager for the client’s portfolio, effectively saving an entire layer of cost: the management fee of the actively-managed mutual fund.

In other words, if the financial advisor can reproduce a comparably diversified portfolio to what the mutual fund was offering but without the mutual fund and its cost layer – e.g., using ETFs that only cost 0.1% - the advisor can both justify his/her advisory fee and save on total costs to the client! Or stated another way, financial advisors are disintermediating mutual fund managers.

In the past, such a shift – where financial advisors actively manage portfolios themselves – wouldn’t be possible, as the sheer administrative costs to actively monitor and implement an ongoing investment strategy was prohibitive across a large number of clients. However, the rise of advisor technology solutions – in particular, “rebalancing” software that is capable of fully automating the implementation of investment models across an entire client base in a highly scalable manner – means that any financial advisor can implement their investment strategies systematically across all of their clients at a reasonable cost. And the collapse of ticket charges for investment trades (also thanks to technology), along with the bargaining power of large advisory firms, means there isn’t even a material benefit to using mutual funds as a way to pool assets for lower aggregate transaction costs anymore.

Thus, it’s becoming more and more feasible for the average financial advisor - whether operating as an RIA, or as “Rep-As-PM” at a broker-dealer – to squeeze out the mutual fund manager’s fee, and just “do it themselves” on behalf of their clients, eliminating an entire layer of costs to the client… and triggering a massive outflow from actively managed mutual funds along the way!

The Passive Mirage: How ETFs Became The New Stocks

Of course, the caveat is that for a financial advisor to shift from selling (third-party) active managers to actually being the investment manager, it’s not only necessary to have the technology to implement the necessary trading and monitoring of portfolio models. It’s also necessary to actually have an investment strategy with views of what to buy and sell, as well as having the investment building blocks to buy and sell.

In the past, the classic building blocks of active management were the building blocks of investment markets themselves: individual stocks (and individual bonds). However, the process of actively analyzing, monitoring, and implementing an entire portfolio of individual securities is still too arduous for most financial advisors. The actual model management and trading implementation itself is feasible – thanks to technology – but the research process would require more staff and resources than what most financial advisors have available. Which means most financial advisors need an alternative “building block” for the investment portfolios they will manage.

And thus the popularity of the ETF. What makes the ETF especially valuable to the modern financial advisor is that, thanks to the proliferation of ETFs across indexes, asset classes, and sectors and industries, they are granular enough for an advisor to pick and choose which ones to buy and sell, but still pooled enough to avoid the (impractical) pressure of analyzing each individual security. In other words, in the past investment managers would manage stocks; most financial advisors, by contrast, manage (pooled and already somewhat diversified) ETFs instead. In this context, the proliferation of ETFs – that cut up available investment markets in ever-more-finely-sliced ways – may be dangerous to the individual consumer (who may not fully analyze what they’re buying, or diversify properly), but has been a boon to the financial advisor.

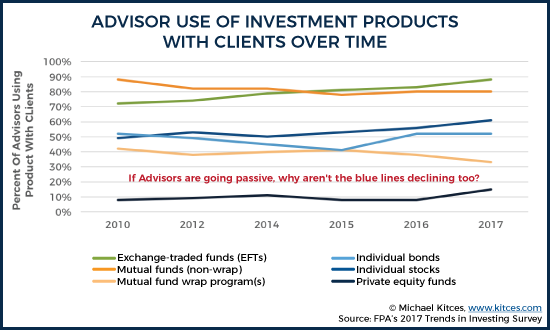

Accordingly, the FPA’s latest 2017 Trends In Investment Survey of Financial Advisors finds that since the financial crisis, advisor adoption of ETFs has continued to steadily rise, now surpassing the adoption of mutual funds, which has been slowly declining (along with the use of mutual fund wrap programs).

The key insight of this trend, though, is that the rise of ETFs does not necessarily represent a shift to passive investing. First and foremost, it’s crucial to recognize that despite the total net outflows from mutual funds, the overwhelming majority of financial advisors are still using them. In other words, advisors aren’t eschewing mutual funds entirely and going passive. They’re mixing together mutual funds with other investment vehicles like ETFs. Because in some areas, hands-on mutual fund managers still add perceived value (to the advisor), and the advisor’s value was analyzing and selecting the mutual fund manager; in other words, though, it’s easier just to bring down the cost for the client, and buy an ETF basket.

Even more important, though, is the realization that while the use of ETFs has been on the rise, the use of individual stocks and private equity funds is also rising. And after a few years of declining, the use of individual bonds is rising as well – which makes sense if financial advisors feel the need to more actively manage bond allocations in the face of potential inflation and rising rates (as the spike in individual bonds perfectly coincides with when the Fed first began to raise interest rates at the end of 2015).

In other words, if financial advisors were truly shifting towards passive investing, then the use of stocks, bonds, and private equity funds should be on the decline along with mutual funds. Except that’s not the case. Instead, mutual funds (and mutual fund wrap programs) are on the decline, but all the building blocks of actively managed portfolios – ETFs, as well as individual stocks and bonds, and alternative active solutions like private equity funds – are rising. What has been labeled a trend of financial advisors going passive, via the growth of ETFs, is just a mirage.

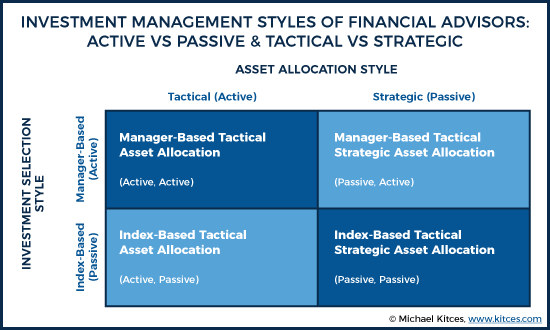

Or viewed another way, there are really two types of “active” investment styles. The first is active security selection, where the underlying stocks and bonds are themselves actively traded, which was/is the domain of most mutual fund managers (and a few financial advisors perhaps). The second is active asset allocation selection, which may also be more active (tactical), or passive (strategic). In the past, most financial advisors strategically held active funds; now they’re actively managing passive vehicles. Which is not a shift from active to passive, but simply a shift in where the active management occurs.

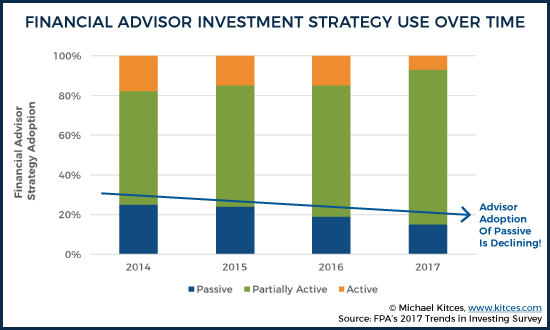

The point is made even more clearly in a follow-up question in the FPA Trends in Investing survey, where they asked whether financial advisors think it’s better to manage portfolios actively, passively, or a blend of the two (where a blend would effectively be “partially active”, and likely a representation of index-based tactical asset allocation). While this survey question has only been included since 2014, the trend is clear: not only is passive investing not on the rise, but financial advisor interest in passive investing is actually declining!

The bottom line: financial advisors are indeed shifting in their investment approach, but the shift is not to passive investing. Instead, “true” passive/passive investing – those who strategically hold passive index funds – appears to be little more than 15% of the financial advisor marketplace. Instead, the real shift is to actively (tactically) managing passive index-based investment vehicles – in other words, advisors who manage portfolios with ETFs, not passively hold them. Because doing so can substantially reduce the end-cost to investors, without the advisor undermining their own advisory fees!

Implications For The Future Of Investment Management

Given the currently dominant industry dialogue that “financial advisors are abandoning active management for passive ETFs”, the implications of recognizing that financial advisors are actually just disintermediating mutual fund managers to bolster their own value proposition and advisory fee are profound.

For instance, it suggests that the drive of actively managed mutual funds to launch and distribute actively managed ETFs – in the hopes of (re-)recapturing outflows leaving mutual funds – is likely doomed to fail. Because the real reason advisors are shifting is that they don’t want to sell someone else’s active management strategy packaged in a fund the client could just buy themselves – and the fact that the active fund is an ETF instead of a mutual fund doesn’t change that outcome. To the extent that financial advisors are continuing to use a subset of actively managed funds, it’s because the advisor believes that the value of the active manager justifies the cost.

Which means asset managers should perhaps spend less time trying to figure out how to chase the hot investment vehicle (relaunching their active mutual funds as active ETFs), and focus more on lowering the costs and improving the performance of the funds directly (to get through the advisor-as-gatekeeper’s investment screens). Because the primary reason a financial advisor as investment gatekeeper doesn’t choose a particular actively managed fund (or refuses to take a meeting with an investment wholesaler) isn’t usually a matter of the vehicle (mutual fund vs ETF); it’s the fact that the SPIVA Year-End Scorecard showed that, over the past 15 years, a whopping 92% of US large-cap and 93% of US small-cap managers underperformed their benchmarks after expenses!

In fact, as financial advisors increasingly become the investment manager themselves, there is a rising trend of advisory firms taking the necessary steps to adhere to Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS) and become GIPS-compliant firms. In other words, advisory firms aren’t trying to differentiate by the track records of the mutual fund products they sell; they’re trying to differentiate with their own GIPS-compliant investment performance track records!

Of course, there is a dark side to the shift of financial advisors to becoming investment managers as well: just as with mutual fund managers, not all of them will be very good at it (not to mention the growing evidence that the available pool of alpha is shrinking as well). In the past, poor investment performance of an individual financial advisor was difficult to determine, in part because every client had a different portfolio, and also because performance reporting tools for clients – that accurately calculated performance against a benchmark – was difficult. But now, between the rise of firm-wide performance reporting under GIPS, and even “just” individual performance reporting with a wide array of tools like Orion, Tamarac, and Black Diamond, clients will know how well their financial advisors are really doing in managing their portfolios. And will soon see that some (or even “many”) aren’t actually all that skilled at investment management, either. Particularly when, for so many financial advisors, investment decisions are still just a part-time task in between client meetings, prospecting for new business, and actually managing the advisory firm itself as a business. In fact, a recent study from Cerulli found that home-office-designed portfolios were beating (Rep-as-PM) advisor-created portfolios by about 50bps on average.

In turn, this will likely lead to a demand from advisors to find alternative ways to bring managed portfolios to clients, while still trying to reduce costs relative to the traditional mutual fund manager. Which bodes well for various Separately Managed Account (SMA) and Turnkey Asset Management Platform (TAMP) providers, as long as they can keep their own costs lower than the typical mutual fund manager fee. Though the TAMPs and SMAs themselves (along with mutual funds) are now being threatened with a new stage of advisor tech evolution: the rise of the model marketplace, where advisors can manage their own models directly through rebalancing software, but aren’t responsible for designing and creating and monitoring the models (which is done by a third-party provider). Which in turn creates the potential for Indexing 2.0 solutions that eliminate the mutual fund or ETF wrappers altogether, where the advisor simply uses the model marketplace software to manage models of individual stocks and bonds directly.

Unfortunately for most financial advisors, the fact that many will likely ultimately end out further delegating investment authority – because they don’t really have the time, knowledge, or inclination to “do it themselves” as the investment manager of client portfolios – will put even more pressure on them to justify their own advisory fees, driving a further shift towards delivering comprehensive financial planning advice and other niche-oriented value-adds to their clientele. Which, ironically, may become the point when more financial advisors truly begin to adopt real passive investing strategies – at the point that “investment performance” itself is truly no longer a value proposition, at the level of the mutual fund manager or financial advisor as investment manager. But until there is a larger shift of financial advisors away from investment-centric value propositions and over towards a core value proposition of financial planning, the trend towards “passive investing” will remain one where financial advisors aren’t really going passive en masse, but are disintermediating active mutual fund managers by using passive index-based vehicles like ETFs as the building blocks of their own active investment management strategies.

So what do you think? Have you been shifting away from mutual funds and towards ETFs? Do you construct purely passive and strategic portfolios, or do you use ETFs as the building block to tactically manage your clients? Where do you see the financial advisor value proposition in the future? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!