Executive Summary

As financial advisors feel increasing pressure to differentiate themselves, a recently emerging trend for those who (actively) manage client portfolios is the idea of charging clients not an AUM fee that is a percentage of assets, but instead, a performance-based fee that is a percentage of upside (or outperformance of a benchmark index), where the advisor’s fee is forfeited if he/she fails to achieve the required threshold or hurdle rate. Such a compensation structure would compel active financial advisors to eschew closet indexing and really, truly, try to outperform their benchmarks – which can be a very compelling proposition to prospective clients.

However, the reality is that performance fees have a very troubled past. Because while a performance-based fee does incentivize the advisor to not be a closet indexer and own a substantially different portfolio than the benchmark, one of the “easiest” ways to do so is simply to take on more risk and amplify the volatility of the portfolio. After all, if the markets rise substantially – as they do on average – a high-volatility portfolio will often provide a substantial performance fee in a bull market. In when the inevitable bear market occurs, the “worst case” scenario for the advisor is simply a year of zero fees.

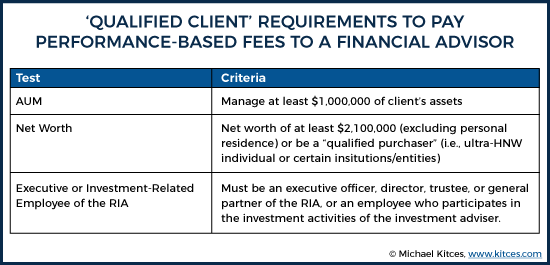

In fact, this “heads the advisor wins, tails the client loses” asymmetry of performance fees is why when Congress created the Investment Advisers Act for RIAs in 1940, it banned most financial advisors from charging performance-based fees at all to retail investors (and of course, brokers under a broker-dealer cannot charge performance fees because they are not serving as actual investment advisers in the first place!). It was only in 1970 that Congress partially relented and allow RIAs serving as investment managers to mutual funds to charge performance fees, and only then if it was a “fulcrum fee” where the advisor participates in both the upside for outperforming and at least some of the downside for underperformance. In turn, it wasn’t until 1985 that the SEC began to allow RIAs to charge performance fees in certain situations to retail clients, and even then the offering must be limited to “Qualified Clients” who meet one of three financial tests… either: a) $1M of assets under management with the RIA charging a performance fee; b) a $2.1M net worth (and thus are presumed to be financially experienced and “sophisticated” enough to understand the risks inherent in performance fees); or c) be an executive officer, director, trustee, or general partner of the RIA, or an employee who participates in the investment activities of the investment adviser.

In addition, it’s notable that research over the years on incentive fees in the context of mutual funds has failed to find any sign that incentive fees are actually associated with better risk-adjusted performance anyway. Instead, the research finds that – perhaps not surprisingly, given the problematic history of performance-based fees – mutual fund managers compensated by incentive fees tend to just generate higher returns by taking more risk, and then amplify their risk-taking activity further once they fall behind their benchmarks! Ironically, though, the researchers did find that mutual funds with incentive fees are more likely to attract client assets, suggesting that substantial consumer demand remains for paying investment managers via performance fees!

Nonetheless, the real-world operational challenges of executing what would be a more complex billing process, the revenue volatility that financial advisors introduce to their businesses (particularly if they use a fulcrum fee structure which means if the advisor underperforms, they really do take the risk of seeing their fees cut substantially), the limitations of only offering a Performance Fee structure to affluent Qualified Clients in the first place, and the conflicts of interest that must be managed, suggests that a widespread shift towards performance fees for RIAs is not likely in the near future… especially as many firms seek to shift their value propositions away from being centered around the investment portfolio and towards financial planning and wealth management instead! But for those RIAs who want to pursue charging performance fees on investment portfolios, it is an option… at least for their Qualified Clients who want to take the risk!

Fulcrum Or Other Performance Based Fees For Financial Advisors

One of the most popular and consumer-friendly aspects of the traditional “Assets Under Management” (AUM) fee is the fact that it aligns the incentives of the advisor and their client. To the extent the advisor charges a fee that is a percentage of the portfolio being managed, favorable investment results that grow the portfolio will grow the amount that the advisor can bill, and losses in the client portfolio will decrease the advisor’s billable assets. Thus, advisors charging AUM fees have a strong incentive to be good stewards of their clients’ money and see the portfolio grow, because growth for the portfolio is growth for the advisor’s business, too.

Yet the caveat of the AUM fee is that it only goes “so far” to align the incentives of the advisor and client. To the extent that markets themselves tend to grow on time – which generally happens regardless of the effort or role of the financial advisor – a portfolio’s AUM fee will tend to naturally rise over time, simply due to passive growth of the market itself. Yet the advisor is “rewarded” with higher fees for growth that the advisor wasn’t responsible for in the first place. In fact, an advisor who persistently underperforms a benchmark in a bull market will still earn the bulk of his/her annual fee increases anyway! For instance, if the market rises by 10% and the advisor underperforms by 1%, his/her AUM fee will still increase by 9% for the year, despite the poor (relative) performance!

As a result, in recent years there has been a growing discussion of whether financial advisors, particularly investment-centric ones whose value proposition is built around their investment process, should be charging some kind of performance-based fees instead. Because with a performance-based fee, the advisor’s compensation can be curtailed for underperforming a benchmark (even if the portfolio itself was up with the market). And if the advisor participates to a greater extent in the relative outperformance of the benchmark, the advisor has an extra incentive to try to beat the benchmark.

Thus, for instance, an advisor might charge a performance-based fee that provides for sharing 10% of the portfolio’s profits – which means the greater the profits, the more the upside for the advisor and the client. Alternatively, the advisor might charge a “fulcrum fee”, which stipulates that the advisor earns a base fee (e.g., 1%), but only earns an additional fee if a specific benchmark target is achieved – for instance, the advisor is compensated 10% of the outperformance above a return threshold (e.g., excess returns above a 7%/year hurdle rate) or for beating a certain benchmark (e.g., returns in excess of the S&P 500 return for the year). Notably, though, a fulcrum fee would also penalize the advisor for underperforming; for instance, if the portfolio substantially underperforms the benchmark, the 1% base fee might be forfeited altogether.

Yet notwithstanding the intuitive appeal of performance-based fees or fulcrum fees, the reality is that they have a very troubled past in the investment world. Which is why in most cases, investment advisers are actually banned from charging such performance-based fees in the first place!

How Performance Fees Incentivize Dangerous Risk-Taking

While performance-based fees provide greater reward potential for good investment managers – giving them a greater incentive to try to outperform, with the potential for investors to attract better managers who want to pursue that upside potential – the caveat is that performance fees can also incentivize managers to take more risk in order to pursue that upside.

For instance, consider a financial advisor who is going to manage a client’s equity portfolio, and will be benchmarked to the S&P 500. The advisor’s performance-fee agreement stipulates that he/she will receive 20% of any outperformance above the benchmark. If the advisor doesn’t beat the benchmark, the advisor earns nothing, as the fee is zero, ensuring the advisor has a very strong incentive to deliver outperformance!

But it turns out that the advisor’s “investment strategy” to achieve outperformance is not to try to pick superior investments and have a high active share. Instead, the advisor will be a closet indexer with a rather simple strategy: since markets go up more often than they go down anyway, the advisor simply puts all of the clients’ assets into a 2X leveraged fund that provides 200% of the daily return of the S&P 500 (e.g., ProFunds UltraBull S&P 500 Fund, ticker symbol ULPIX), and waits for the bull market’s leveraged returns to produce stints of substantial outperformance on which the advisor will earn performance-based fees.

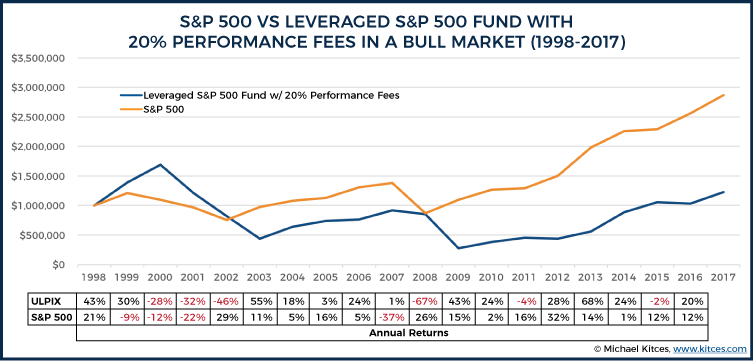

In point of fact, since the fund’s inception in late 1997, ULPIX would have outperformed its S&P 500 benchmark in 11 out of 19 years (from 1998 to 2016 inclusive), in many years by more than 25% (and as high as 54.5% outperformance in 2013!).

Yet if the investor had started with $1,000,000 in the portfolio, at the end of 20 years, the portfolio of ULPIX paying 20% performance fees would only be worth $1,226,744, for a cumulative return of just 1.1%/year. In the meantime, the financial advisor generating performance fees would have “earned” performance-based fees of $454,526! In the meantime, if the investor had simply bought the S&P 500 and held it without the advisor involved at all, the portfolio would have grown to $2,867,761 (for an average annual return of 5.7% over this time period).

The end result: by taking substantial risk with the client’s portfolio and amplifying the volatility, the performance-fee-based advisor was able to demonstrate several years of strong outperformance (for which he generated a substantial profit), while the client alone experienced (sometimes dramatic) losses in the down years. Yet all the advisor did was buy a volatility-amplified index fund… which meant the performance-fee-based advisor generated substantial fees for providing little actual value to the client, as the advisor really just profited from the additional volatility to the upside (not his/her actual investment prowess), while the client bore the brunt of the inevitable losses that followed from the high-risk portfolio!

Why The Investment Advisers Act Of 1940 Bans (Most) Performance Fees For RIAs

The fact that performance-based fees can incentivize investment managers to take additional risk – which enriches the advisor during up markets, but can severely damage the investor’s portfolio during down markets – is not a new phenomenon. In fact, Congress recognized the problem in the aftermath of the bull market of the 1920s and the crash of 1929 and Great Depression that followed. And as a result, when the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 was written, Section 205(a)(1) explicitly established a ban on (most) performance-based fees for investment advisers! Because as Congress noted at the time, performance fees were effectively “heads I win, tails you lose” arrangements.

Specifically, the Investment Advisers Act provides that:

No investment adviser… shall enter into, extend, or renew any investment advisory contract… if such contract provides for compensation to the investment adviser on the basis of a share of capital gains upon or capital appreciation of the funds or any portion of the funds of the client.

In other words, after the destructive consequences of performance-based fees in the Crash of 1929 where investment advisers participated in the upside appreciation and capital gains of their investors in the preceding years (and even amplified the volatility with margin lending), but didn’t have to bear the pain of the subsequent losses to the downside in the crash, Congress banned performance fees for registered investment advisers in the very legislation that created RIAs in 1940. Instead, investment advisers were required to charge assets-under-management (AUM) fees, or a flat dollar amount (e.g., a retainer-style management fee).

In 1970, though, the SEC began to partially relax the Performance Fee rules. First, the Investment Advisers Act was amended to allow RIAs serving as the investment manager of a mutual fund to charge “Fulcrum Fees” (where the advisor can earn a performance fee to the upside but also must decrease its fee proportionately for underperforming the specified benchmark threshold) under the then-new Section 205(b).

And then in 1985, the SEC further relaxed the rules on performance-based fees for retail investors in Release IA-996, establishing Rule 205-3 which stipulated that investment advisers could charge certain performance-based fees when working with a “qualified client”.

For the purpose of performance fees, a “qualified client” is one that meets either an AUM test, a Net Worth test, or is an executive or investment-related employee of the RIA itself. The AUM test requires that the investment adviser actually be managing at least $1,000,000 of the client’s assets (originally $750,000, but increased to $1,000,000 in 1998 under IA Release 1731). The Net Worth test requires the (qualified) client to have a net worth of at least $2,100,000 (up from an original threshold of $1.5M, now annually indexed, and since 2012 investors may not include the value of their personal residence in meeting this net worth test) or be a “qualified purchaser” (ultra-high-net-worth individual, or certain institutions/entities) under Section 80(a)-2(a)(51). And the “employee” test requires that the qualified client either be an executive officer, director, trustee, or general partner of the RIA, or an employee who participates in the investment activities of the investment adviser.

Notably, as mentioned earlier, a Registered Investment Company (i.e., a mutual fund) is also able to charge performance fees, but only if they meet the Fulcrum Fee structure requirement of Section 205(b)(2) of the Investment Advisers Act. On the other hand, hedge funds (limited partnerships that are treated as unregistered securities) are permitted to charge any type of performance fees, although they in turn are limited to only accredited investors.

Nonetheless, the key point is that a registered investment adviser that wants to charge performance-based fees to its “retail” investor clients can only do so if they are “Qualified Clients”. And of course, Series 6 or Series 7 “advisors” under a broker-dealer are not permitted to charge performance-based (or any advisory) fees at all, as they can only be compensated for brokerage services (unless they become a “hybrid” adviser and separately join or become an RIA as well).

Structuring Performance Fees And The Upside And Downside Of Fulcrum Fees

For investment advisers working with retail clients who are Qualified Clients, it is permissible to charge Performance Fees, but it’s still necessary to determine the actual structure of the performance fee itself.

Some firms simply arrange their fees to participate in a percentage of the upside (e.g., 10% or 20% of profits), while others stipulate that their performance fees are only paid if they exceed a certain threshold (e.g., 20% of profits above a 5% return, or 10% of the outperformance of a particular index or benchmark). In some cases, the only fee that is payable is the performance fee; in other cases, the performance fee may include a baseline AUM fee as well – for instance, 1% of the portfolio plus 10% of the excess return above a certain threshold.

In the case of mutual funds, to limit the potentially problematic incentives and conflicts of interest of performance-based fees, Congress explicitly required under Section 205(b)(2) of the Investment Advisers Act that the fee must provide for:

“Compensation based on the asset value of the company or fund under management averaged over a specific period, and increasing and decreasing proportionately with the investment performance of the company or fund over a specified period in relation to the investment record of an appropriate index of securities prices…”

In other words, a valid performance fee in the case of mutual funds must have some set measuring period of which investment performance will be compared to the underlying index, and the advisor’s compensation must both increase and decrease proportionately based on those results.

In practice, this type of performance-based fee is typically known as a “fulcrum fee”, where the investment adviser receives some “base fee” compensation, and the advisor’s fee is then increased for outperformance and the base fee is decreased for underperformance, to reduce the risk that the performance fee constitutes a “heads I win, tails you lose” structure. (Although notably, the “worst case” scenario would typically still only be that the advisor may forfeit all of their fee and have it reduced to zero, while the investor may experience outright losses, as there is no requirement for a “negative” or refundable fulcrum fee arrangement!) Nonetheless, given that the fulcrum fee approach reduces the potential adverse incentives for investment advisers to take more risk to earn higher performance fees (since they also have more downside risk), the approach is increasingly popular, even for RIAs serving Qualified Client retail investors (and not just managing mutual funds).

In addition, it’s also important to note that since IA Release 721 in 1980, a “contingent advisory fee” arrangement, an indirect version of a (non-proportionate) fulcrum fee where the advisor just receives a base fee (not a percentage of the performance upside) but does forfeit his/her fee for underperformance (e.g., where the advisory fee is waived if performance fails to clear a certain hurdle rate) will still be treated as a performance-based fee, necessitating a Qualified Client arrangement. Although a subsequent 2004 SEC No-Action letter to Trainer, Wortham & Co affirmed that a “satisfaction guarantee” refund option (where the investor can request a refund if they are unhappy with their investment advisor relationship, regardless of performance results), is permitted as long as the advisor’s fee truly is not contingent on meeting any specific investment performance threshold.

In the case of performance fees for state-registered investment advisors (i.e., RIAs with less than $100M under management), the RIA must adhere to state-level rules on performance-based fees, which may (but do not always) conform to the SEC’s regulations under the Investment Advisers Act for SEC-registered investment advisers!

Is It Worth Trying To Charge Performance Or Fulcrum Fees?

While there is some clear intuitive appeal to charging performance-based fees as a way to align the interests of the investment adviser and (Qualified) client, the mixed record of actual outcomes for performance-based fees still leave much to be desired.

As noted earlier, Congress banned performance-based fees for RIAs more than 75 years ago because of the consumer harm caused by their conflicts of interest (particularly the incentives for financial advisors to take excessive risks with client portfolios while hoping for a few good “volatile” up years), and while the rules have relaxed to some extent in recent decades, it has only been for more affluent “Qualified Client” investors who – right or wrong – are “presumed” to be more financially experienced and sophisticated and at least recognize the risks of the arrangement.

Though notably, in the context of financial advisors in particular, performance-based fees introduce non-trivial business execution challenges as well. For instance, with performance-based fees, there is a natural temptation to make trades for the biggest clients first, as getting better results for the biggest clients first amplifies performance-based fees (since for the same favorable trade that outperforms the benchmark, the performance fee is bigger for outperformance on a $10M portfolio than a $1M portfolio). In the context of a mutual fund or hedge fund charging performance-based fees, this is less of an issue, because all clients participate equally in a pooled investment fund (though may still be a problem if the RIA serves as investment manager of multiple mutual funds of varying sizes); in an RIA working with retail investors, though, where it is typical to have multiple clients of varying sizes holding varying portfolios guided by numerous different investment policy statements, the issue of how trades are sequenced and allocated, along with fair execution (and being able to demonstrate that the RIA meets its Best Execution obligations), really matters.

In addition, performance-based fees can also create substantial short-term revenue volatility for the advisory business itself. Of course, to some extent, this is the whole point of the performance-based fee – to give the financial advisor more “skin in the game” and a greater incentive to really, really try to outperform. Nonetheless, even the best investment managers may not find their strategies favored at all times, especially if performance-based fees are calculated by the “typical” quarterly billing process for an advisor. In fact, even annually-calculated performance-based fees can introduce substantial business pressure – as if the advisor only bills its performance fee annually, and has a single bad year, it means the business must run with all of its overhead costs for 2 full years because the next potential annual performance billing period! Some advisors might aim to “smooth” the performance calculation over multiple years to partially ameliorate this risk, but that means recent clients may end out being charged a performance-based fee for a long-term performance track record that predates when he/she was actually a client in the first place! (I.e., the client may end out being charged for performance that occurred before he/she ever showed up.) Alternatively, some advisors use a blended base-AUM-fee-plus-performance-fee structure to manage this business risk, but the combination of the two can potentially distort the incentives for the RIA again, as the structure returns to a “heads I win” (with performance fee) and “tails I don’t lose” (with AUM fee) outcome. (Which, again, is why Congress mandated a Fulcrum Fee structure for mutual funds under Section 205(b)(2)… to place the base fee under at least some risk in the event of underperformance.)

In addition, while with modern technology, it is potentially possible to have each performance-based fee calculated individually for each client – given that most RIAs do not investment client assets on a pooled basis, and so clients who start at different times may have performance fees calculated from different starting points –in practice many of the typical portfolio performance reporting and billing software solutions for RIAs do not have robust performance-based fee calculation modules (given how uncommon fulcrum and other performance fees are, in light of the Qualified Client requirements!). Which relegates the RIA to a more manual Excel-spreadsheet-based billing process that can be time-consuming at best, and at worst introduces manual billing errors. And under Rule 204-2 of the Investment Advisers Act, the SEC does expect a meticulous set of Books and Records to track all (performance-based) fee calculations!

And of course, there’s still the challenge that, even as performance-based fees are trying to come back into vogue, there’s still little evidence that they actually lead to better investment outcomes. An especially well-cited analysis by Elton, Gruber, and Blake in the Journal of Finance on incentive fees (in the context of mutual funds) found that funds charging performance fees did tend to have positive stock selection ability, but the best funds tended to actually have lower betas (and as a result the total return was not improved and the incentive fee often wasn’t even earned!). The remaining funds tended to have better relative performance, but only because they took more risk than non-incentive-fee funds, and their risk-taking behaviors tended to increase further after a period of poor performance (i.e., managers earning performance-based fees tended to take outsized risks trying to make up for losses to get back to their incentive-fee thresholds). Which meant in the end, the mutual funds using performance-based fees did not as a group exhibit superior risk-adjusted performance results to non-incentive-fee funds… though ironically, the researchers did note that incentive-fee funds attracted more new cash flows, suggesting that the concept is highly marketable, even if it doesn’t actually result in persistently better outcomes!

From a practical perspective, though, the biggest caveat and limitation to charging performance-based fees as a financial advisor is that, beyond the compliance oversight obligations, it’s necessary to be under an RIA (and not a broker-dealer), and limit the firm to working with Qualified Clients who meet the portfolio and/or net worth requirements in the first place (and/or to be structured as a hedge fund that works with similarly-affluent Accredited Investors instead). Which may be feasible for a subset of the largest RIA firms with the most affluent clients that can meet the Qualified Client minimums… except the largest RIA firms already are enjoying the fastest growth thanks to their marketing economies of scale and the fact that more affluent clients already tend to gravitate to the largest firms (regardless of whether they charge performance-based fees). And of course, focusing on performance-based fees may be very unappealing for more holistic financial planning and wealth management firms, that are trying to focus clients on the broader range of services they provide, and not accentuate focus on investment results alone.

Nonetheless, for RIAs that want to charge performance-based fees – whether under a mutual-fund-style fulcrum fee, or some other arrangement – and are ready and willing to work with Qualified Clients, it is an option under current law to do so, as long as all the rules and requirements are met. But it’s still crucial to be certain the firm properly manages its conflicts of interest, particularly when it comes to not just trying to “earn” performance fees by taking more risk with the clients’ investment dollars!

So what do you think? Are performance-based fees likely to grow in popularity in the coming years? Or should the SEC revive the restrictions of old on performance-based fees because of the unhealthy incentives for advisors to take greater risk in client portfolios? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

[Michael’s Note: Special thanks to Chris Stanley of Beach Street Legal, a law practice and compliance consultancy, for his insights about the history of performance-based fees for RIAs and fulcrum fees for mutual funds!]

A risk adjusted performance fee would be a solution against taking on more risk. For example use a sharpe ratio.

How to cut your fee in half:

Ask any active advisor who promises you out performance if he is willing to get paid (at leasr half of the fee) by a riskadjusted performance fee like a sharpe ratio.

No advisor would agree to that because most of them would never get paid.

There are of course many problems as with all fee structures like outperform (higher sharpe ratio) in a year with negative returns.

But a base fee plus some sort of riskadjusted performancefee would be a fair deal for a customer.

It also changes the way advisors think. (Try it) What would you do differently if you got paid for outperformance based on sharpe ratio?)

People have been discussing this my whole career (30 years), it sounds interesting and clients may like it when the balances and markets go down, but they don’t want to pay the upside.

Two things: (a) Most RIA’s do not charge performance fees because they are abysmal at generating alpha (preferring instead to overcharge clients at fixed fee percentages where those RIA’s fees vary little whether good markets or bad). And, (b) Performance Based Fees DO NOT incentivize risk taking. On the contrary, when a majority of your compensation is dependent on generating consistent, absolute returns (not relative returns as most pedantic RIA’s do) you must FIRST make sure you DO NOT LOSE MONEY and then focus on generating Alpha. No RIA that charges PB Fees wants to be in a recoup-the-loss situation, so PB Fee RIA’s are usually very conservative.

Do you have a source that: (a) RIAs with PB fees generate alpha better than traditional fee on AUM RIAs? (b) RIAs that have PB fees are generally very conservative portfolios?

I am a 25 year practitioner – not an academic. My many years, along with those of managers like me that have absolute disdain for asset-allocation based, high fixed-fee RIAs that do not charge PB fees, is that, yes, our returns are both higher and more consistent given our research and preference for individual securities (versus products) and so, yes, our portfolios are indeed more conservative. A common definition of conservative may be the hackneyed one of lower volatility. My definition of conservative is exposure to absolute loss and via this definition managers, like me, that charge PB Fees are solely geared to not lose money first and then generate absolute returns because a loss must be recouped. “Managers” (really = asset gatherers) that rely on standard asset-allocation through products and who are comfortable offering and discussing with clients negative relative returns (one cannot eat relative returns) are by definition less conservative.

So you have no sources for either claim other than the anecdote of your own firm’s performance? Sounds very biased.

I read this articles with great interest as a friend of mine was approached by a RIA out here in AZ that doesn’t have a fund setup but charges a AUM/Performa fee. The kicker is they assess the AUM fee on a monthly basis and the performance fee on a quarterly basis. They charge 20% A QUARTER ON PERFORMANCE and 2.5% AUM fee. And their run by 20’somethings with little financial background and a shady ADV.. Would you guys agree if you look at FEES & COMP this is a perfect example on how certain “advisors” are getting away with murder and committing outright fraud that state regulators are not seeing whats in front of them

https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/IAPD/Content/Common/crd_iapd_Brochure.aspx?BRCHR_VRSN_ID=427039