Executive Summary

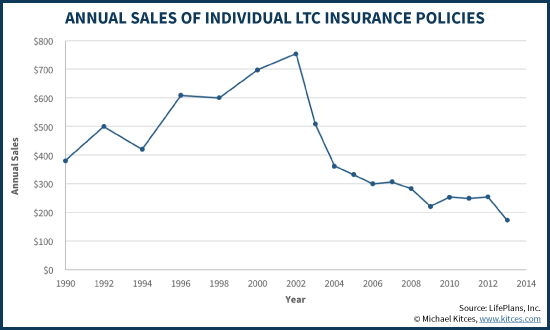

Despite being around for nearly 40 years, and enjoying preferential tax treatment for nearly half that time period, long-term care insurance has struggled to gain momentum in the marketplace. In fact, low interest rates, coupled with low lapse rates, and rising longevity, have come together to drive up long-term care insurance premiums significantly, leading LTC insurance purchases to decline nearly 70% from their peak in 2002.

However, a new approach to long-term care insurance pricing – the Performance LTC policy from John Hancock – is aiming to bring LTCI premiums down. Ironically, the new policies have eliminated any kind of pricing “guarantee” to prevent premiums from rising, but combined that change with an opportunity for policyowners to benefit if investment and claims results are favorable in the future, by accumulating “Flex Credits” that, like dividends from a participating life insurance policy, can be used to reduce future premiums and even allow LTC premiums to vanish, altogether.

The good news of this structure is that it is uniquely suited to benefit if interest rates rise in the future (unlike hybrid life/LTC or annuity/LTC policyowners who may suffer in a higher rate environment). The bad news, however, is that because Hancock is not actually a mutual insurance company, it will still face a fundamental conflict of interest in deciding how much to pay as a Flex Credit to policyowners, versus a dividend to shareholders. Nonetheless, though, the reality is that by allowing LTC insurance premiums more flexibility, Performance LTC may still potentially be less expensive LTCI coverage in the long run!

The Challenge Of Pricing Long-Term Care Insurance Premiums

Long-term care insurance originated primarily as nursing home insurance in the late 1970s, but it didn’t really garner much interest until the 1990s, as the earliest baby boomers began to reach their 50s (and their parents hit their 70s and 80s). Adoption accelerated further after the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996 gave long-term care insurance the tax-qualified treatment it (still) enjoys today.

However, even as long-term care insurance received its favorable tax treatment, in the 20 years since the volume of long-term care insurance being purchased has fallen, and huge swaths of insurers (including even some mega-insurers like MetLife) have left the business altogether. The problem is that when trying to effectively price long-term care insurance – as insurance with a relatively high probability of claims in the first place – relatively “small” mistakes in the underlying actuarial assumptions have a dramatic impact.

For instance, it’s estimated that as little as a 1% change in interest rates correlates to a 15% required change in premiums to keep an LTC insurance policy actuarially sound. Having a 1% lapse rate instead of a 5% lapse rate can increase future claims for an insurer by as much as 50%. And of course, that’s before considering the potential impact of medical advances that prolong life expectancy in the face of serious illnesses (which may be good news for the individual, but can greatly amplify claims against an LTC insurance policy, too)!

In fact, given the difficulty in estimating these key inputs correctly, leading LTC providers like Genworth are struggling to be profitable in issuing long-term care insurance. The combination of falling interest rates and “surprisingly” low lapse rates in the past decade has revealed that pricing was so far off, companies could not honor their original prices, and instead had to request State Insurance Departments to permit premium increases as large as 85% on huge swaths of existing policies (and forcing consumers to decide how to deal with the new higher rates). Yet even with the rate increases, LTC insurers haven’t been able to raise the premiums fast enough to keep up with their earlier underpricing challenges, leading many to just leave the business altogether.

In turn, this dynamic has put significant pressure on long-term care insurance providers to get the pricing “right” up front – which basically means setting the premiums on new policies even higher, to be even more conservative (as if the company has to request a rate increase in the future, it has probably already lost any chance to be profitable on that policy!). As a result, the cost of new LTC insurance policies has exploded even more than the premium rate increases on old ones. Data from LifePlans finds that the cost of a new LTC insurance policy for a 60-year-old increased by 145% from 1995 to 2010.

The end result is that LTC insurance providers find themselves between a rock and a hard place. If the long-term care insurance policy is not priced high enough to protect against these uncertainties in the first place, then the insurer may be unable to regain profitability with rate increases later. Yet raising rates on new policies so much has taken its toll as well, as the number of long-term care insurance policies purchased by consumers fell by a whopping 65% from 2002 to 2012!

The ultimate irony of this situation is now that we “know” lapse rates for long-term care insurance may be no more than 1%, and now that we “know” interest rates can go so low, the risk of needing to raise long-term care insurance premiums in the future has never been lower than it is today. In fact, if interest rates increase, LTC insurance providers may discover that they actually could have priced policies lower than they did. But without knowing when an interest rate increase will occur, LTC insurance providers have no way to know how much premium relief to provide in advance… since there’s been no effective means to make adjustments along the way. Until now.

John Hancock Performance LTC (PLTC) And The Flex Credit Account

To resolve the challenge of wanting to make long-term care insurance premiums more flexible, but having great difficulty being able to adjust the premium itself after the fact, last year John Hancock innovated a new approach to long-term care insurance, which they dubbed their Performance LTC (PLTC) policy.

The key new concept with John Hancock’s Performance LTC is the creation of the “Flex Credit” – a payment that the insurance company makes back to the policyowner every year, in recognition of both favorable investment experience of John Hancock’s General Account (where policy reserves are invested) and the claims experience of the entire block of its Performance LTC policies.

The annual Flex Credit is deposited into a Flex Account, and the balance of the Flex Account can then be used to reduce (i.e., pay for some or all of) the premium of the policy. Which means if interest rates rise (and/or claims turn out to be more favorable than expected), Flex Credits make it possible for the Performance LTC insurance premiums to decline in the future. (Notably, Flex Credits deposited in the Flex Account can also be used to pay for long-term care needs in the future, such as during the policy’s elimination period, instead of just using them to reduce LTC premiums.)

In other words, the Flex Credit of the Performance LTC policy operates similar to a dividend from a participating whole life insurance policy. To the extent that future claims (or the insurance company’s investment returns) turn out to be better than the original (conservative) projections, the ‘excess’ results will be returned to the policyowner in the form of either an "Insurance Credit" or an "Interest Credit", to help reduce future premiums. Given the potential (but still looming uncertainty) for interest rates to rise in the future, this provides the buyer of Hancock’s Performance LTC policy a way to participate in the upside of interest rate increases, even better than Hancock’s prior Benefit Builder Custom Care III policy (and unlike with a hybrid life/LTC or annuity/LTC policy, where the policyowner is far more likely to be adversely impacted by rising rates!).

The added benefit of the Flex Credit structure is that even if John Hancock prices its long-term care insurance “conservatively” – i.e., sets premiums higher than may be necessary for projected claims, just in case the underlying LTC assumptions shift unexpected in the future (as they did in the past!) – if the future turns out to be more favorable, or merely just “normal” as expected, the Flex Credits will just be paid out even faster, reigning in those higher premiums in the future.

Rising LTC Premiums And Flex Credit Offsets

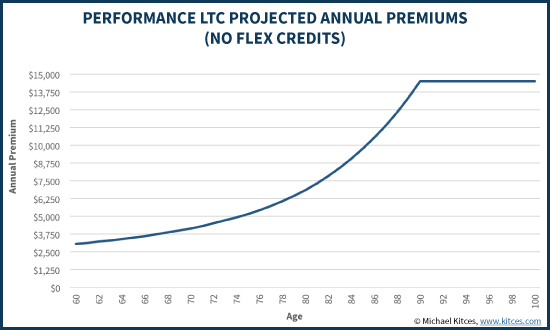

Given this new dynamic, though, Hancock’s Performance LTC policy deliberately prices itself very “conservatively”. In fact, its standard version, with a 3% inflation rider, is assumed to have premiums that will rise every year... potentially quite significantly, if there were no Flex Credits available to offset them. For instance, the chart below shows the expected premiums for a 60-year-old male purchasing a Performance LTC policy with a $200/day benefit, a 5-year benefit period, and the aforementioned 3% compound inflation rider.

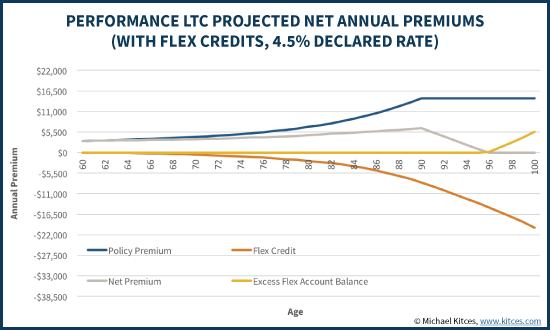

Of course, the caveat is that these premiums would not actually be due unless the policy paid no Flex Credits, ever. Which would require that John Hancock’s General Account never earn a return above the 2.5% “Threshold Rate” required to generate the investment portion of Flex Credits, and furthermore that claims were far higher than expected (e.g., 65% higher due to significant medical advances extending claims periods). Which means even if the investment and claims results are “merely” adverse – for instance, if John Hancock’s General Account only has a Declared Rate of 4.5%, and claims are 35% higher than current expectations – some Flex Credits will still be earned, and the net premiums will be significantly lower than originally projected (albeit still rising for much of the time period).

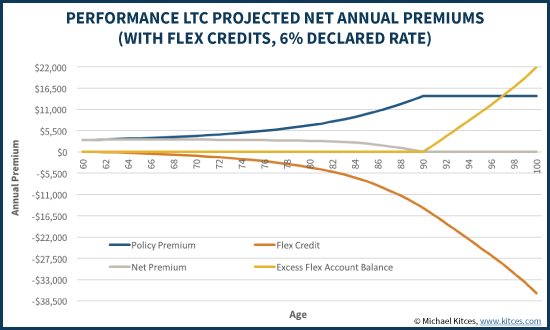

On the other hand, if the claims experience is even more favorable, and interest rates do rise (such that the Declared Rate goes to its available maximum of 6%), the net premium result with accumulating Flex Credits in the Flex Account just looks even better. The version below shows the net premium for the Performance LTC policy at a 6% Declared Rate, and claims that are (still) 10% higher than Hancock’s current expectations.

Notably, in this scenario the results are so strong, the Performance LTC premiums only ever rise cumulatively by about 5% in the first few years (before any material Flex Credits are being paid), and then begin to fall in the years thereafter… such that if the insured is actually still alive in his/her late 80s, the premiums decline significantly, and vanish altogether once the policyowner reaches his/her 90s! In fact, the Flex Credits – which by then are more than enough to offset the entire policy premium, even with all the increases – are so large that the excess balance just accumulates in the Flex Account, forming an additional pool of money that can be used for (non-covered) claims, and/or is simply paid out at the death of the policyowner.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that this more favorable outcome will occur. The actual investment and claims experience for John Hancock’s General Account and its Performance LTC policies may not be this good. But if the results are favorable, the policyowner benefits in the form of the Flex Credit. And alternatively, if the results end out being even better – for instance, if it turns out that Hancock’s claims assumptions are now so conservative, that future claims come in lower than expected – the accumulation of Flex Credits just improves even further.

How Does Performance LTC Pricing Compare To Genworth And Other LTC Providers?

For many prospective LTC insurance buyers, the fact that John Hancock’s Performance LTC premiums are projected to rise – even by a little bit in the relative “good” scenario of moderate claims and higher interest rates – may be concerning. But it’s crucial to recognize that the flexibility of the policy’s pricing has a significant impact on the base premium of Performance LTC in the first place. Because while every other long-term care insurer must price conservatively, once, up front, John Hancock doesn’t need to be as conservative at the beginning, because it knows that premiums will rise to cover future contingencies. On the other hand, if the conservative pricing turns out not to be necessary, the policyowner still benefits.

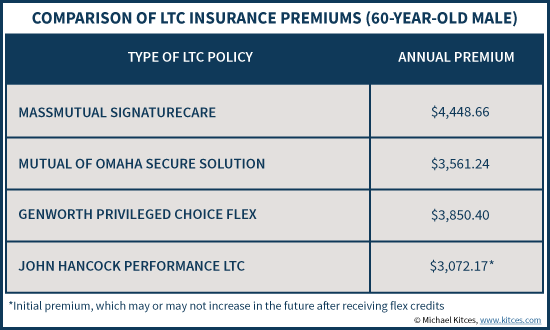

Thus for instance, the chart below compares similar LTC insurance policies from other popular carriers, including the MassMutual SignatureCare policy, the Mutual of Omaha Secure Solution, and Genworth's Privileged Choice Flex 3. All policies are for a 60-year-old male, with a $200/day benefit, 5-year benefit period, and 3% compound inflation rider.

As the quotes reveal, John Hancock’s Performance LTC is far less expensive from the start. As a result, in the scenario where interest rates and claims are favorable but premiums “still” rise by about 5%, the reality is that the Hancock policy will still be far less expensive than the others. In fact, even in the “adverse” scenario with a 4.5% Declared Rate and claims that were 35% above projected, it still takes 10-20 years for the Hancock Performance LTC policy to have higher premiums than the others. And it takes almost 30 years for the cumulative premiums to be higher (since the Performance LTC buyer would have had years of much-lower premiums before they eventually caught up).

In other words, while the premiums of John Hancock’s Performance LTC policy are much more likely to experience at least small changes (given the expected rising premiums and the non-guaranteed nature of the Flex Credits), the policy’s flexibility still allows it to be cheaper than the rest by a significant margin. Or viewed another way, policyowners are actually paying a significant “excess” premium in today’s marketplace to other LTC insurance carriers to obtain that premium “guarantee” (notwithstanding the fact that it’s still not unequivocally guaranteed, because the carriers may still raise rates for an entire class of policyowners in a particular state, as has occurred with some frequency for many of these carriers in the past!).

Caveats And Concerns Of The Performance LTC Insurance From John Hancock

Notwithstanding what appears to be rather appealing pricing for the Performance LTC policy – at least compared to the available alternatives – there are several notable caveats and concerns to consider, both in terms of this new approach to LTCI pricing, and also details of the Performance LTC policy itself.

How Flex Credits Are Calculated

First and foremost, there’s the operation of the Flex Credits themselves. While arguably it takes some highly adverse interest rate and investment results, on top of especially horrific claims experiences, there is still a danger that Flex Credits won’t be paid at all (or at least, at a rate far less than illustrated earlier). The longer it takes interest rates to rise, the less that will be paid in Flex Credits over time. And there are virtually no Flex Credits at all for the first several years (as the insurance company is still recovering its commission and other distribution costs, so the premiums technically aren’t yet being allocated to the insurance company’s reserves to earn a Flex Credit return yet).

In addition, the reality is that the accumulation of Flex Credits will differ depending on the insured…

It’s also important to recognize that if policy results are especially unfavorable for a period of time, where investment results of the General Account are below the Threshold Rate, and/or claims are especially bad, the allocation of Flex Credits can be negative for that year. Notably, negative Flex Credits do not cause the loss of any dollars already paid into the Flex Account, but may mean that year’s premium rises (because there were Flex Credits to offset premiums in the prior year but less or none in the current year). Furthermore, if Flex Credits are negative, the “loss” is carried forward, and there are no future positive Flex Credits until all the prior negative ones are offset. Which means bad results, early on or at any point along the way, could trigger an indirect increase in LTC premiums (either by not getting Flex Credits that were being received in the past, or simply because Performance LTC premiums will rise in every year that [rising] Flex Credits aren’t available to offset them).

No Waiver Of Premium And Other Performance LTC Features

Beyond the structure of the Flex Credits itself, there are some other notable issues to consider with Performance LTC as well.

Most significantly, one key difference of Hancock’s Performance LTC is that the policy does not have a Waiver Of Premium feature – common in virtually all other LTC insurance policies – which eliminates LTC premiums once the insured goes on claim. Instead, the policyowner is actually still required to pay premiums, even while on claim. Furthermore, it’s notable that because claims can actually impact the calculation of Flex Credits, a policy that is paying claims may actually experience an indirect net premium increase at the same time, as the Flex Credits may level off or decrease (even as the underlying base premium continues to rise!).

For those who find the 3% compound inflation rider to be insufficient – given the potential that future long-term care inflation may be higher than this – Performance LTC does offer a 5% compound inflation rider as well. In addition, the 5% inflation rider does not use the annually-rising-premium-offset-by-Flex-Credits structure. Instead, the 5% compounding version has a level premium (before being reduced by Flex Credits). As a result, though, the 5% compound inflation rider is dramatically more expensive than 3% inflation; thus, while the 3% compound inflation rider quoted above has a base premium of $3,072/year (before subsequent premium increases and subsequent Flex Credit offsets), the 5% compound inflation version of the policy is a whopping $9,629/year (such that those who prefer a larger inflation rider will likely choose other LTC insurance carriers, even with the potential for Flex Credits).

On the other hand, the good news is that the Performance LTC policy does still offer a Shared version of the policy for married couples (any accumulated and unused Flex Credits in the Flex Account simply flow to the survivor’s Flex Account balance).

Can You Really Buy Participating LTC From A Non-Mutual LTC Insurance Company?

The idea of having an insurance policy that is “conservatively” priced, with any future improvement in actual claims resulting in a refund to policyowners, is not new. It is the basis for “participating” whole life (and other participating insurance) from mutual insurance companies, which similarly pay a dividend (literally treated as a return of premiums) if future policy results (claims and investment results) are better than originally projected.

However, a key distinction is that when it comes to participating life insurance from a mutual insurance company, the structure “works” because a mutual insurance company is literally owned by its policyowners. So if the policy is priced conservatively and then turns out to perform better than expected, the insurance company “profits” by doing so, but those profits go back to the very policyowners who bought the insurance in the first place. This closed loop system reduces most incentives for the insurance company to try to “game” the payment of dividends – because if the insurance company underpays the dividend and generates a larger profit… it goes back to the policyowners as a dividend anyway.

In the case of John Hancock and its Performance LTC policy, though, the situation is somewhat different. John Hancock is owned by Manulife, and Manulife Financial (ticker symbol: MFC) is a publicly traded shareholder-owned (Canadian) corporation. Which means if Performance LTC policies are “more profitable” than expected, such that the company pays Flex Credits back to the policyowners, those Flex Credits will detract directly from the Manulife profits and the availability of dividends to pay to actual shareholders.

In other words, the fundamental different between Performance LTC’s Flex Credits and the dividends of participating life insurance is that the latter is from a company actually owned by its policyowners and paid to its policyowners, while the former is from a company owned by third-party shareholders but making payments to policyowners. Which means Hancock’s decision about how much to allocate in Flex Credits each year faces a fundamental conflict of interest between serving its policyowners and serving its shareholders.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that anything nefarious is afoot, but it does raise serious questions about the incentives that John Hancock will have to not necessarily pay “the maximum it could pay” in Flex Credits, given that paying less in Flex Credits improves the profitability of the company for its shareholders (who are not the Performance LTC policyowners). In other words, John Hancock may face some perverse incentives to not necessarily maximize the Declared Rate on its General Account, and to be ‘conservative’ in releasing any excess reserves if policy claims really do turn out to be more favorable than expected. Which is concerning, as those are exactly what Performance LTC policyowners are counting on to get the Flex Credits they “need” to keep their premiums from rising precipitously over time!

LTCI Premium Stability And Vanishing Premium LTC Insurance

Notwithstanding the concerns of whether John Hancock has the “right” incentives to maximize Flex Credits for Performance LTC policyowners, arguably this new LTC insurance approach may still be superior to the “traditional” way that long-term care insurance is priced.

The reason, as noted earlier, is that in practice the efforts of insurance companies to “guarantee” long-term care insurance premiums – given the significant uncertainty that is actually involved in doing so – is driving up LTC insurance premiums, to the point that fewer and fewer can afford the coverage at all. In other words, trying to price LTC insurance once, up front, is forcing insurance companies to make the premiums so high – to be conservative, given the challenges of getting subsequent rate increases approved by State Insurance Departments – that it’s causing the premiums to be unaffordable altogether.

By contrast, eliminating the implied rate guarantee for LTC insurance coverage – as John Hancock has done – introduces the possibility, and even the likelihood, that LTC insurance premiums may rise slightly over time (or more rapidly, if Flex Credits ultimately underperform). Nonetheless, it also means those premium increases are likely to be small and gradual over time, and that John Hancock should have very little risk of ever needing to put through some massive 50% - 85%+ premium increase all at once. In part this is because it would simply have raised premiums more evenly over multiple years. But it is also because the ability of premiums to rise slightly over time (paired with not paying out a Flex Credit) also avoids a situation where the insurance company has to wait for state approval to raise premiums, which some suggest has only exacerbated the magnitude of recent rate increases.

Which means ironically, the Performance LTC structure may actually lead to better LTC premium ”stability” – not by necessarily guaranteeing premiums will remain level, but by allowing enough flexibility to reduce the risk they ever need to rise precipitously all at once. Which in turn allows consumers more time to adjust to the higher premiums, conform higher premiums in later years to the declines in other spending that typically come for older retirees, and avoids putting policyowners in the position of deciding what to do about a mega premium increase that hits all at once.

On the other hand, the great challenge of the new Performance LTC approach is that it’s very difficult to assess the likelihood that the current sales illustrations will in any way match what actually occurs in the future. Not merely because the future itself is uncertain, but because a prospective policyowner is very limited in the information that be assessed about the underlying policy assumptions in the first place. In other words, there’s a risk that current sales illustrations are still being overly optimistic in projecting future Flex Credits – such that LTC premiums seem to disappear altogether as the policyowner approaches age 90. And unfortunately, we’ve been here before – participating life insurance policies in the late 1970s and early 1980s were also commonly sold on the assumption that future dividends would cause premiums to vanish within 20 years, and instead the policies so underperformed those projections (as interest rates declined in the 1980s) that it eventually led to a wave of “vanishing premium” class action lawsuits! Will Performance LTC someday face its own questions as future in-force illustrations in 5-10 years fail to align to the original sales illustrations?

Nonetheless, the fact remains that the ‘traditional’ approach to LTC insurance has not fared well for the industry, and arguably the nature of trying to “guarantee” LTC insurance premiums has only exacerbated the situation. Which means eliminating the guarantee and creating a structure where LTC premiums can ‘float’ (based on rising premiums and not-guaranteed-to-offset Flex Credits to reduce them) may bring down the cost of LTC insurance on that basis alone. And the fact that we may see rising interest rates in the coming years – which should only further improve the payout of Flex Credits – means Performance LTC is uniquely positioned as the type of LTC insurance most likely to benefit from rising rates (unlike hybrid LTC insurance policyowners, who may suffer from the failure to participate in higher interest rates).

Still, at a minimum, those who consider buying the new Performance LTC policies from John Hancock will need to be cognizant of the fact that while premium increases may be more gradual, it remains to be seen whether Hancock will really be able to pay out Flex Credits as projected, even with rising interest rates, especially when doing so conflicts with company’s desire to maximize profitability for its shareholders!

Thanks to Jerry Skapyak and Mark Maurer of Low Load Insurance Services for their assistance in providing some of the LTC insurance quotes and supporting information used in this article.

So what do you think? Is "participating LTC insurance" a good strategy to manage the challenges of LTCI pricing? Do you "trust" that John Hancock will pay the Flex Credits as expected? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

If I’m remembering correctly, at least one version of the MassMutual SignatureCare policy had a dividend that could start in year 10. The concept was to address the issue of rising premiums when the client needed the coverage the most.

I’m sure they couldn’t market it as a vanishing premium (both because of that terminology and because the dividends were not guaranteed) but it was essentially designed that way.

Elliott Weir

Michael – I enjoy your analysis, but on this one you did not do your homework, nor did the folks over at Low Load Insurance Services.

John Hancock did not “innovate a new approach” to LTC with this — they stole an approach mutual companies have used for years. Northwestern Mutual was the first with a participating LTC contract, introduced in 2002 (and they furthermore grandfathered in all existing policyowners since the product began in 1998) and has paid out ~$57.8 million of dollars in dividends to policyowners since then. As I understand it, NY Life and Mass Mutual also allow for participating dividends, though they have not actually paid any yet.

A stock company trying to use this approach is amusing, but it is clearly hampered in its effectiveness with its inherent inefficiencies and conflicts of interest (as you point out). And in Hancock’s case, with a struggling LTC book of business, this is clearly an attempt to bring a new gimmick to market.

Given that John Hancock is the only one attempting this as a stock insurance company, I would still contend that it is ‘innovation’ to try to design a participating policy in that context.

That aside, the captive insurance companies selling through only captive agents make it EXTREMELY hard for independent advisors to evaluate such policies. If the companies would open up their distribution to be supportive of independent advisors, so we can evaluate and vet them, there would be more coverage of what they’re apparently working on. 🙂 Until then, it’s difficult for me to write about policies as an independent advisor when the companies provide little means to gather information in the first place. :/

Though I appreciate the feedback, and will try to explore further.

– Michael

Thanks for the reply, Michael. I do understand your point, however with very few players in the LTC market at all (and several of them mutual), it wouldn’t take a lot of homework for someone to discover what I pointed out. In fact, all of the numbers and figures I just gave you came from a Google search that linked directly to public press releases from Northwestern Mutual. Again, I just think that before you state something as “the first”, “brand new”, or “innovative” there should be homework done to make sure that is the case. In no way do I impugn your journalistic character; in fact, it is precisely because you are so respected and well-balanced in your approach that I felt compelled to point out that you did not quite reach your own standard on this one.

As an aside, while independent advisors may not like it, there are a few good reasons why captive insurance companies keep some or all of their products distributed only through their agents, including lower cost of distribution and the ability to have at least some control over the training and quality of their sales force.

All in all, keep up the good work – I enjoy reading your posts.

Understood, and appreciate the feedback. 🙂

– Michael

InsuranceOldie, as you seem to be familiar with the Northwestern Mutual product, may I ask- are their dividends contractual? The one thing that stands out to me on the Hancock product is that it

is contractual and it’s the most specific wording I’ve seen in a policy

regarding any kind of credits being offered to a policyholder. Also, would you know if NWM has any limitations such as Mass Mutual’s caveat of not paying dividends to a policyholder until the 10th policy anniversary or age 65, whichever is later? That was another benefit of Hancock’s that stood out to me, that they will share the the good (and of course if there is bad) with the policyholders from the first anniversary and even have expectations that the policyholder would have a $0 premium at some point due to the credits, which is something I didn’t think was available with the others.

Kristy – The northwestern product does not have any contractural limitations on paying a dividend before 10 years or age 65. My policies did pay dividends before both of those milestones. The dividend, as all dividends at a mutual company, are not guaranteed. Northwestern is the only company to have paid LTC dividends, and has been paying dividends on all product lines, when they generate excess surplus. Last few years, they have paid in excess of $5 billion per year in dividends.

On thing on Genworth: Keith Maurer told me that Genworth is going to be just fine because they are getting out of the life insurance business. This will make them cash flush since all underwriting, sales, marketing and future reserve costs for LI disappear; he indicated that this will put them in a great position to do fine in the LTC space moving forward especially since now they have a clear understanding of their actuarial risk after these initial years’ experience.

Overall a great article Michael. John Hancocks Performance LTC is a step in the right direction but the comparison to Dividend paying Whole life is not exactly an apples vs. apples comparison because in the case of LTC — as Michael points out — the base premium is not guaranteed contrary to a guaranteed premium of a Whole life policy so that if the Flex credits are not paid/generated the policyowner does not get the benefit of a level premium as in the case of Whole life. This needs to be made very clear to the client and am not certain at this point enough emphasis has been shed on that by producers to their prospective clients.

Which traditional LTC plans have premium guarantees?

None to my knowledge provide an outright premium guarantee. At best, they’re guaranteed renewable with premiums that can still be adjusted on a class basis.

The hybrid LTC policies do provide an LTC premium guarantee, but only because they control the cash value and do NOT provide any guarantees on the crediting rate, which makes the cost guarantee a total mirage. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/is-the-ltc-cost-guarantee-of-todays-hybrid-lifeltc-or-annuityltc-insurance-policies-just-a-mirage/

– Michael

Michael, thank you for a great perspective on the Hancock Performance LTC product! I think it’s a great opportunity for policyholders to be provided better expectations of what future premiums could look like. I know that Transamerica still offers a 3-year rate guarantee to their TC3 product in the current market, but as we’ve seen in the past, most increases occur further out than that. I like the opportunity that the Hancock product provides to clients in that they could actually have a decreased premium in the future and that the Flex Credits are contractual as opposed to the dividends of other carriers being discretionary. Again, great article and thank you for sharing such great information!

Only one way of getting a virtual locked in premium for LTC is to use One Americas whole life with LTC rider and then add on the lifetime LTC rider.

But insurance is for one purpose: to forestall economic risk. If you’re trying to do that, why add a LTC policy to a Life Insurance policy? These have two very different purposes.

If someone needs a LI policy, why would you risk it by spending down the money for LTC? Alternately, if someone needs LI, why dilute it with a LTC policy? I suppose the argument is for the stable premium. In that case, this JH option would presumably fit the bill.

LI and LTC insurance work, as far as I can see, at cross-purposes. This must seem like heresy since these hybrid policies have become so popular.

I can see an annuity with a LTC rider. That makes sense even though they are rather pricey. Now your risk mitigation is more aligned.

If we’re thinking about client best interest, I just don’t see how a hybrid LI policy makes sense except for the stable premium argument. But then I don’t sell insurance so maybe I’m missing something?

What are the Federal Income Tax consequences of Flex Credits? Are there any Private Letter Rulings on the subject?

To the extent you’re getting premia back, I would imagine no tax consequence. To the extent the flex credit exceeds the total premia paid… that’s a good question.

Oh Michael, this is by far and away the very best article I have seen on this product offering, but it contains one major flaw. As someone who is also keenly aware of the disincentives for non-mutual carriers to be faithful in maximizing dividends to their life insurance policyholders, I did my research when Performance LTC hit the market.

The manner in which the Flex credits are awarded to PLTC policyholders is not subject to the whims of the C-suite individuals. And there is every bit of self-interest on their part to maximize the credited interest rates to the reserves allotted to this book of business as well as lowering their insurance costs.

Thus, both policyholder and the Wall Street focused C-suiters have parallel interests. This is precisely why I am so excited about this product design.

Thomas,

Perhaps I’m reading something wrong in the specimen policy, but I see Flex Credits tied to a Declared Rate that is a subjective decision of company leadership. And as far as I can tell, a decision to underpay on the Declared Rate would result in at least a short-term bump to the profitability of the block (which only gets more profitable if lower Declared Rate = lower Flex Credits = higher premiums = higher lapse rate).

Again, I’m not trying to say that I believe Hancock is trying to be nefarious about this at all. But I’m still looking at a subjectively determined Declared Rate that has problematic incentives for company leadership to choose a lower number…?

– Michael

I have great news for you and your readers Michael! Exactly what you described was taken into account in the development of this product and the ‘leeway’ that JH leadership has with the allocation of the Declared Rate towards the Flex Credits is limited to one half of one percent.

So, if as you and I believe is true that interest rates are bound to rise in the future, then the Flex Credit will rise right along with the investing ability of the JH professionals.

If this happens and/or if they have been ultra conservative in their estimate of claims and the Flex Credit is larger than projected, then this product becomes oh so attractive. The policyholder can shift 25, 50, 75 or 100% of their credit into their Flex account. These funds can then be used to fill in all of the ‘benefit holes’ that you and I don’t like. Pay the premiums with the Flex Account, and pay the care expenses during the Elimination Period ,and pay for those home modifications, and pay for care in the months that your expenses exceed you monthly benefit max, and then when you die, your Shared-Benefit spouse will get all of your unused Flex Account dollars. Finally, when she dies, the kids will get the Flex account dollars as a death benefit with a maximum set at ‘lifetime premiums paid’ so as to avoid income tax issues.

I so hope to read a future column in which you add a couple more of your terrific graphs with some of the delicious possibilities that this very innovative product offers. If 2015 is the low water point in the long term care insurance business, it will in large part be due to John Hancock putting real effort behind their claim to being the leader in LTCi.

Thank you once again Michael for the highly informative article. I agree with you that there is risk for the policyholder to rely upon the issuance of future Flex Credits to reduce the premium.

The price of the JH Performance LTC contract is presently high relative to contracts that do not carry this risk. The policyholder will need the issuance of Flex Credits simply to bring the JH Performance LTC pricing back to where alternate carrier premiums are currently at.

Regardless of which inflation protection is opted for (however we slice it and dice it) the premiums with John Hancock are much higher than the premiums are elsewhere, generally ~65% higher.

You mention within your article that John Hancock’s premiums for it’s level premium policy, 5% compound inflation protection are very high and consumers will look elsewhere. Well, the same cost of insurance exists throughout this contract, Michael. John Hancock does not change its internal COI just because the consumer opts for 5% compound vs. 3% compound. It’s just packaged differently. The 3% compound option is just packaged as a Guaranteed Purchase Option with increasing graded premiums whereas the 5% compound option has level premiums rather than graded premiums. Pay me now vs. pay me later.

Thought of another way, your 60 year old male hypothetical above always has the option under the John Hancock Performance LTC policy to REJECT the purchase options of 3% compound.

So, the John Hancock Performance LTC price to purchase $6000 month, 5 year benefit period, and no inflation is $3072.17 with the possibility that the issuance of Flex Credits will reduce the $3072.17 annual premium.

Your 60 year old male could opt to buy this same amount of coverage of $6000 month, 5 year benefit period, $360,0000 pool of money — rejecting 3% compound purchase options— with Mutual of Omaha for $1840.08, Genworth $1980.00, Northwestern Mutual $2328.00, Mass Mutual $2523.25.

So, it is clear the cost of the money is initially set at a much higher cost within the John Hancock Performance LTC contract relative to other underwriters.

Most consumers (if given a choice) will elect to pay lower premiums out of the gate rather than to rely upon the issuance of Flex Credits just to get even.

Jack,

I’m not sure I follow your quotes here. The $3,072 premium for the Hancock Performance LTC example here DOES include a 3% inflation rider. No surprise that other non-inflation policies price cheaper. Once you put the inflation rider back, the others are more expensive (per the quotes I included in the article itself), at least initially. Obviously if the Flex Credits do NOT manifest, and the Hancock policy premiums rise, that policy will NOT be the cheapest in the long run.

I’ll grant that we don’t do a ton of LTC business, but I have yet to see the initial-year Hancock policy price higher than competitors in a matching-policy head-to-head comparison. It’s always been cheaper. The huge wild card is that it only stays cheaper if the Flex Credits show up. But if interest rates rise (or mortality and morbidity improve, or lapse rates rise) the Flex Credits at least make it feasible that the policy stays cheaper. So at that point, it’s a forecast on interest rates and/or other shifts in the underlying pricing factors.

– Michael

Michael,

Performance LTC’s option to include 3% compound inflation is a purchase option, albeit a forced option. The policyholder is agreeing to purchase more benefit on an annual basis in the future (3% annual growth) for additional escalating annual premium. The policyowner though can elect TO NOT accept the 3% compound inflation protection. If the policyholder declines an option, no additional inflation protection will be applied until age 91. The initial premium of $3072 in your example is simply the cost to purchase the initial BASE $6000 monthly long term care benefit. Any additional increases of 3% compound inflation are accounted for by the increasing premium John Hancock is charging.

I understand you state you do not do a ton of LTC business, however I can quickly show you examples of level premium policies being less expensive to start with than JH Performance LTC.

50%++ of all LTC applicants are women:

For example, simply change your article’s example of a single Male applicant age 60 to a single Female applicant age 60:

John Hancock $4640.00 with increasing premiums,

Mass Mutual $4448.60 with level premium.

John Hancock just announced today it is discontinuing individual LTC insurance sales. Thankfully, this Performance LTC policy will no longer be marketed to consumers as it just was not a good consumer value with its built-in rate increase structure. The trend with long term care insurance sales is moving strongly towards asset-based hybrid policies fixed guaranteed premiums.

Jack,

Indeed, I just saw the news as well.

Unfortunately, the “guaranteed” premiums on the asset-based hybrid policies is just a mirage, given that the investor surrenders control of their capital and the insurance company has sole control over the crediting rate. It’s actually drastically EASIER for LTC insurers to raise the implied cost and profitability of hybrid policies over traditional LTC, especially in rising rate environments, as I’ve warned about in the past (see https://www.kitces.com/blog/is-the-ltc-cost-guarantee-of-todays-hybrid-lifeltc-or-annuityltc-insurance-policies-just-a-mirage/).

I can only hope that if the marketplace shifts more towards asset-based policies, that the insurers are not abusive about the relatively unchecked power they have to raise costs by limiting their crediting rate on the policy. Though I don’t think it’s a coincidence that so many insurers are pushing to offer hybrid policies. The actuaries have already shown that it’s really just a giant call option on interest rates for the insurer. This is why we’ve been such advocates of traditional LTC insurance over hybrid policies for our clients…

– Michael

Well, the guaranteed premiums of hybrid policies are not a mirage, as the premiums are in fact guaranteed. However, I agree with your point. The mirage is that the consumers don’t “lose” anything with hybrid policies. Hybrids are marketed as a “win-win” when in-fact the consumer can “lose.” Opportunity cost, especially in rising interest rate environments, and asset-offset cost if an LTC claim is made.

That being said, I am glad that Performance LTC is off the market as I felt the policy was an awful consumer option when compared to other traditional LTC policy options currently available today.

The problem is the traditional LTC policy marketplace is getting very thin.

Thank you for sharing this information. If you need help on learning how to avail life and health insurance just visit our website. https://healthywealthfit.com/do-life-insurance-agents-make-good-money