Executive Summary

The Investment Policy Statement (IPS) is a staple of investment management and provides crucial guidance for (discretionary) investment managers about how to implement portfolio strategies on behalf of a client in times of uncertainty (when the client may not be there in person to help make the decision).

Yet the reality is that the concept of a “policy statement” transcends just the world of investments. Arguably, it can be effective across most domains of financial planning – not necessarily to establish a plan of action for the advisor in the absence of the client, but for the client today to establish a plan of action for handling an uncertain future. In this context, the “financial planning policy statement” is a form of choice architecture, narrowing future decisions in a manner that can help to eliminate the “bad” emotional choices from consideration.

Of course, it’s still necessary to establish appropriate financial planning policy statements in the first place, linking underlying client values and core beliefs to structured policies that are flexible enough to address future unknowns, yet specific enough to provide clear, actionable guidance when the time comes. Which means the financial planner needs both a means to discover and understand a client’s values and beliefs (not just the financial data), and the tools to formulate and test policies that might be recommended to the client.

Overall, though, this kind of “policy-based financial planning” approach actually has the potential to provide the crucial link between financial life planning and technical financial planning strategies, serving as a means to translate values and beliefs into structured policy statements that can be implemented with the client. At least, if financial planning software is ever improved to the point that such financial planning decision rules can be illustrated in the first place!

Why An Investment Policy Statement Matters

An Investment Policy Statement (IPS) is an agreement between an investor and a (typically discretionary) investment manager, setting forth the guidelines for how portfolio investment decisions will be made. Its fundamental purpose is to ensure that when the investment manager must make decisions in moments of uncertainty, there are guiding policies and principles in place to help ensure the decisions are consistent with the investor’s goals and desires.

Typically, an IPS will include details about the client’s investment objectives (time horizon, expected contributions or withdrawals, risk tolerance, etc.), the desired investment strategy (passive, active, tactical, strategy, etc., and targeting conservative principal preservation, or moderate growth, or aggressive growth), the types of investments/securities that can be used (e.g., ETFs and mutual funds, but no individual stocks or illiquid alternatives), and any relevant constraints (e.g., must maintain at least 40% diversification into bonds, must have domestic and international asset classes, only use funds with a high sustainable investing rating, and no investments that generate UBTI in a retirement account).

Notably, a key aspect of the IPS is that it’s not actually “too” specific about what the investment manager will actually do with the portfolio from day to day, month to month, and year to year. In fact, the whole point of an IPS is that it’s meant to leave the investment manager enough flexibility to handle whatever market surprise might occur – from the financial crisis to Brexit, or a surprise election outcome – while still providing enough guidance that the investor doesn’t end up surprised later by what the investment manager actually did in the portfolio.

From a practical perspective, using an IPS is important for discretionary portfolio managers (including most RIAs who have discretion) to be able to defend that they had permission to do what they did in the portfolio – i.e., it is a defense against getting sued if the advisor can establish that the portfolio was implemented in a manner consistent with the agreed-upon IPS.

But at a broader level, an Investment Policy Statement is also a good example of how financial decisions, especially in moments of uncertainty, can be guided by establishing a clear policy in advance.

What Is Policy-Based Financial Planning?

The concept of “Policy-Based Financial Planning” was first introduced by Dr. Dave Yeske and Elissa Buie in a July 2006 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning. Their paper, “Policy-Based Financial Planning Provides Touchstone In A Turbulent World”, made the case that just as an investment policy statement can help clients stay the course during turbulent markets, so too can other financial planning policies “help keep clients grounded during turbulent times in their lives.”

In this context, a key contrast is that while the Investment Policy Statement is primarily meant to form an agreement between the client and the advisor (with respect to the portfolio), a financial planning policy statement services primarily as an agreement between the client and their future self. In other words, it’s meant to establish a formal plan upfront, and serve as a guide to the decision-making process in future times of uncertainty… ideally removing the client from making difficult real-time decisions under emotional distress.

Of course, given the breadth of possible scenarios we encounter in the future, the reality is that financial planning policies must – like their investment policy statement brethren – still remain fairly broad (to be able to adapt to whatever the future may hold), yet still be specific enough that when the moment comes, it’s clear what to do. Which means in practice, a good financial planning policy statement should seek to capture the client’s core values and beliefs – those that remain relatively constant and consistent through a wide range of circumstances – and then help to translate them into actionable steps.

For instance, Yeske and Buie suggest that if the client’s core value is an aversion to debt (for whatever reason), the debt policy statement might indicate that credit cards will only be used to buy items that are part of the monthly budget (and repaid in full at the end of every month), that small purchases (up to 10% of income) will be saved for by setting aside money every month to cover the purchase, and for large purchases (costing more than 10% of income, such as a home or automobile) the only debt will be amortizing debt with payments that don’t exceed 30% of gross income. With this kind of policy statement, the next time there’s a decision about whether to open a credit card or not, or finance a purchase or not, there’s a guiding policy statement to make the decision easier.

Similarly, if the client’s core value or goal is “to be financially independent by age 50 in order to realize a dream of creating a nonprofit mentoring program for inner city youth”, the policy statement might entail terms like: we will save 20% of our current income, we will invest savings for growth and diversify across at least four distinct asset classes, and we will insure income against loss to guarantee continuation of savings (i.e., disability insurance).

With this policy statement, not only does a client making $80,000/year know that there’s now a plan to save $16,000/year (20% of income), and split the investment funds to allocate $4,000 per asset class (e.g., into bonds, large-cap, small-cap, and international), but if he/she changes jobs and gets a raise to $100,000, it’s already “known” that the plan will be to raise savings to $20,000 (to maintain the 20% ratio) and replace the prior employer’s group disability insurance policy if the new employer doesn’t already offer one.

Of course, the reality is that many of these policy statements are already embodied in the kinds of financial planning recommendations that advisors commonly make. However, Yeske and Buie suggest that by going through a discovery process to establish the relevant core values and underlying policies with the client directly, the client may be more likely to follow and adhere to the policy statement… as it can serve as a continuous reminder of the core value statements that the client has already made and committed themselves to (which is more effective than the advisor just telling the client what to do!).

Financial Life Planning And Formulating A Financial Planning Policy Statement

Notably, one of the key aspects of policy-based financial planning is that the “How” aspects of the policy statement (what the client will do in various circumstances) should be driven by the underlying “Why” (the client’s core values and related goals). As a result, it’s necessary to have a robust discovery process to collect that relevant information in the first place… not just the client’s financial data, but the values that motivate him/her as well.

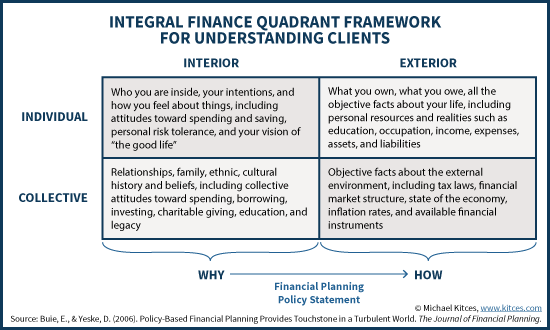

Yeske and Buie suggest that a reasonable starting point would be Integral Finance framework, as discussed by Dick Wagner’s article by the same name in 2002. Integral Finance separates financial planning concerns across two dimensions: the interior vs the exterior, and the individual vs the collective/group. Accordingly, a client’s core financial beliefs and circumstances will span across four quadrants, as shown below.

In this context, the traditional “data gathering” process is focused primarily on the right side (especially the upper right), while the foundation for a financial planning policy statement is to better understand the “Why” on the left. This might be accomplished by an informal conversation with clients about their goals, or a more structured process like the Money Quotient structured discovery tools, Mitch Anthony’s “Financial Life Planning” Tools, or George Kinder’s “Seven Stages of Money Maturity” Financial Life Planner curriculum.

Once the client’s core values have been identified and articulated, the role of the financial planner is to help link those to the relevant financial planning topic areas (retirement, estate, insurance, etc.), and help clients to formulate appropriate policy statements that fit the issue and are consistent with their values statement. Here, the planner’s expertise is crucial to ensure that the policy statement will actually be useful and relevant, given the actual technical issues involved. For instance, helping to spot that even a debt-inclined client with a policy statement to use debt aggressively may still be limited by practical borrowing limits that lenders impose. Or that a financial independence policy statement that targets early retirement should also contend with the challenges of withdrawing from retirement accounts before age 59 ½.

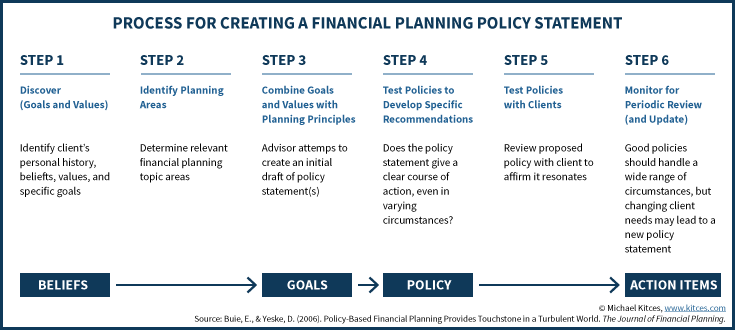

Ultimately, Yeske and Buie advocate a specific six-step process for developing financial planning policies, from Discovery, to Identifying Planning Areas, Combine Goals and Values with Planning Principles, Test Policies to Develop Specific Recommendations, Test Policies with Clients, and Monitor for Periodic Review (And Update). More generally, the key is to start with a basic belief or value, and help the client articulate it into a goal, and then a policy, to ultimately formulate an action item.

The Financial Plan As A Series Of Financial Planning Policy Statements?

As noted in the example above, a financial planning policy statement may not necessarily result in a materially different recommendation in many circumstances. In fact, arguably a “good” financial plan should already be considering all these issues as a part of the client’s needs and goals, and express them implicitly in the financial plan and its recommended action items.

Nonetheless, the virtue of having a consistent financial planning process is to ensure that it is in fact applied consistently, considering all the relevant issues. As a result, it’s not hard to imagine that just as a good comprehensive financial plan covers all the key financial planning topic areas, that the financial plan of the future will include a financial planning policy statement associated with each area. Thus, there might be a saving/spending policy statement, a college funding policy statement, an estate planning policy statement, and a retirement policy statement.

Notably, though, policy-based financial planning has the potential to be more than “just” a values or belief statement that precedes each section of the financial plan. Yeske and Buie make the case that a financial planning policy statement is also a form of “choice architecture”, helping clients narrow down potential choices in times of distress to a more constructive subset. In other words, when “sell everything in a bear market” is not one of the available policy choices – the only options are “Add more in savings at reduced prices” or “Rebalance the portfolio at the end of the year”, the client should actually be more likely to choose one of the latter, and not pursue the panicked choice.

At its best, a financial planning policy statement establishes a series of decision rules about how to handle a wide range of uncertain futures. For instance, the Withdrawal Policy Statement, as pioneered by Jon Guyton, sets forth a series of decision rules about how to handle withdrawals in an uncertain future – for instance, by determining when certain “capital preservation” or “prosperity” rules will kick in, based on how the client’s portfolio and spending have shifted since the original plan. As a result, clients can always “know” when and whether they’ll have to adjust their spending in response to market conditions, even without knowing if/whether the markets will ever rise or fall enough to trigger one of those rules (which is the essence of a robust policy). Or they can use a software solution like Timeline to illustrate in advance how the rules in the Withdrawal Policy Statement would have played out in various historical market scenarios, and then output the final policy rules into a Withdrawal Policy Statement template.

Ironically, though, perhaps the greatest challenge to adopting a more policy-based financial planning approach is that no financial planning software today is written to actually accommodate more dynamic financial planning policies. To the extent that financial planning software is still written primarily to illustrate the need for a financial services product, relatively “simple” financial planning policies like “cut spending by 10% if the market crashes” or “maintain current lifestyle and increase savings by 50% of every raise” are impossible to illustrate.

Nonetheless, Yeske and Buie’s idea of doing “policy-based financial planning” and formulating financial planning policy statements for the key elements of the financial plan, and having a structure to link together “financial life planning” concepts with actionable financial planning recommendations, is arguably a strong vision for the future of financial planning, especially as the profession shifts from its product-centric roots to truly providing ongoing financial advice to help clients navigate their uncertain futures!

So what do you think? Are financial planning policy statements as important as investment policy statements? Does policy-based financial planning help facilitate financial life planning? Will financial planning software evolve to accommodate more dynamic financial planning policies? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!