Executive Summary

One considerable (and unfortunately common) challenge for financial planners is getting clients to focus on the goals they ought to focus on from a purely financial perspective, despite the psychological and behavioral biases which may direct their attention elsewhere. For instance, many households overemphasize accumulating assets (when they should be paying down debt), or overemphasize paying down debt (when they should be accumulating assets). To further complicate things, household preferences for accumulating assets versus paying down debt can sometimes shift in a seemingly confusing manner. However, an interesting new line of research points to one seemingly irrelevant factor which can be lurking in the background and influencing how clients perceive their wealth: whether their total net worth is positive or negative.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – examines research on how our net worth may influence our perceptions of and preferences for holding assets and debt, and particularly the tendency to prefer having more assets when our net worth is negative, but less debt when our net worth is positive.

Mental accounting is a key concept of behavioral finance, which refers to the ways in which we mentally categorize assets, transactions, and other financial information in our heads. In theory, all of our resources should be fungible – dollars are dollars, regardless of what (liquid) account they’re in – but in practice, this is not how we typically behave. A study by Abigail Sussman and Eldar Shafir explores one particular form of mental accounting – the ways we tend to categorize assets and debt based on our net worth. By presenting participants with financial profiles that were equivalent in net worth but varying in the structure of their balance sheets, the researchers found that people tend to prefer having more assets when net worth is negative, but less debt when net worth is positive. For instance, despite the fact that net worth is actually the same -$100,000 in both scenarios, households tend to indicate a preference for having $100,000 in assets and $200,000 in debt over just $10,000 in assets and $110,000 in debt. However, if the assets and liabilities in the scenario above were reversed (i.e., net worth was positive $100,000 instead), then households would tend to prefer simply paying down their debt (even if it means having less in liquid assets)!

And this finding is notable, as it has several important implications from a financial planning perspective. For instance, it can help explain why people struggling with debt tend to accumulate assets and not pay down their debt, even if they're keeping cash in a 0.25%-yield savings accounts while compounding 22% credit card interest rates. Additionally, this may be why affluent clients who can afford lots of leverage still often want to pay down their mortgage. Which, ironically, may mean that the people who can afford to "prudently" use leverage tend to eschew it, while those who can least afford leverage tend to engage in high-debt-profile behaviors that may actually amplify financial fragility! Further, preferences may seem to shift suddenly, particularly as households pay down student debt and begin to move into positive net worth territory, which may (or may not) align with what they should actually be focusing on. And for those who enter positive net worth territory quickly, there may be an overemphasis on paying down debt relative quickly (now that they "can"), rather than saving into investment accounts which may grow at a higher rate in the long-run.

Ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that seemingly irrelevant factors (such as a household’s net worth) can influence how households perceive their financial situation, the decisions they make as a result, and their willingness to keep accumulating assets (while not paying down the debt) versus liquidating assets to reduce their debt profile as well. As a result, the way we as financial planners communicate with clients and frame these discussions can have a big impact on whether clients do (or do not) ultimately adopt our recommendations. Which means it's important to understand the factors which may be lurking in the background and influencing client behavior, even if those factors should (in theory) be irrelevant to a client's behavior!

Note: This post was inspired by a keynote session presented by Dr. Abigail Sussman at the 2018 CFP Academic Research Colloquium. See this post for more information on research presented at the 2018 ARC.

Why Mental Accounting Is Important

Mental accounting—i.e., the way we mentally categorize assets, transactions, and other financial information—is a key concept of behavioral finance. In theory, all of a household’s resources should be fungible—dollars are dollars, regardless of what (liquid) account they’re in—and a household should show no preference for spending from one (mental) account or another, at least as long as both are equally liquid. However, that’s not the way people typically behave in the real world.

Financial planners encounter this behavior often in practice. For instance, clients who are reluctant to spend down an emergency fund (or money earmarked from an inheritance) but happy to pay the expense from their checking account are engaged in a form of mental accounting. Similarly, clients who are reluctant to write a check for a financial planner’s fees but happy to pay those expenses in the form of an AUM fee are also engaged in mental accounting.

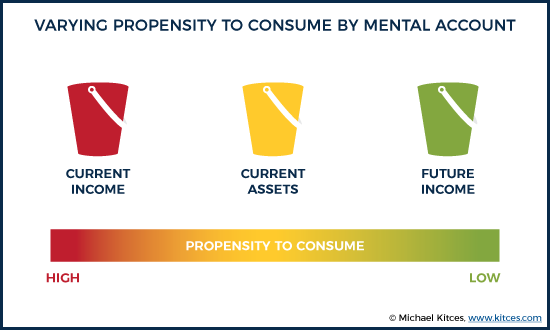

Notably, there can be some genuine benefits to mental accounting. For instance, within Shefrin and Thaler’s mental accounting framework, we prefer to spend—including covering unexpected expenses—from accounts that are mentally earmarked as “current income” (e.g., checking and savings accounts) rather than “future income” (i.e., our marginal propensity to consume varies across mental accounts)… which is probably good, as it helps to provide more internal resistance to liquidating a dedicated retirement savings account.

However, mental accounting can also lead to suboptimal decision-making, which is why it is important to understand in order to help clients make good financial decisions. For instance, it is common for people to separate expenses into categories of “recurring” and “one-time” expenses, but this categorization can lead to overspending if one-time expenses are not properly accounted for in our overall expenses. In other words, we might feel like we’re spending reasonably based on our recurring budget, but our total spending may be unsustainable because there are too many “one-time” expenses (which either cumulatively add up to too much, or sometimes recur more often than we care to admit).

How Our Net Worth Influences Mental Accounting

In Chapter 6 of the CFP Board Center for Financial Planning’s new book, Client Psychology, Dr. Yiwei Zhang and Dr. Abigail Sussman, both of the University of Chicago, examine the role of mental accounting in household spending and investment decisions.

In Chapter 6 of the CFP Board Center for Financial Planning’s new book, Client Psychology, Dr. Yiwei Zhang and Dr. Abigail Sussman, both of the University of Chicago, examine the role of mental accounting in household spending and investment decisions.

As noted earlier, mental accounting can influence our decision-making in many ways, but a particularly interesting way in which mental accounting can influence us is how preferences and mental categorizations may change based on our overall net worth.

How Net Worth Influences Perceptions of Debt and Assets

In a paper publishing in Psychological Science, Dr. Abigail Sussman and Dr. Eldar Shafir examined how positive or negative net worth status influences psychological perceptions of wealth.

The paper covers three studies, each containing two different experiments. In the first study, Sussman and Shafir presented participants with hypothetical financial profiles covering a household balance sheet. In each case, participants were shown two profiles that were equivalent from a net worth standpoint, but varied based on how their balance sheet was structured. Specifically, participants were shown a “low” profile (i.e., low assets and low debt) as well as a “high” profile (i.e., high assets and high debt). For instance, Sussman and Shafir present the following example pair:

Mr. Green has $200 in assets, $44,200 in debt.

Mr. Red has $42,100 in assets, $86,100 in debt.

Notably, in the example above, both Mr. Green and Mr. Red have a net worth of -$44,000, though the composition of their household balance sheets differ. Mr. Green is the “low” profile (i.e., low assets and low debt) whereas Mr. Red is the “high” profile (i.e., high assets and high debt).

Participants were then asked to consider which individual they felt was better off financially (with additional instructions clarifying that each household was similar in all other regards—i.e., neither household was constrained in their ability to access credit). And they concluded that, despite the equivalent net worth and the larger total amount of debt, Mr. Red was in a better financial position, because he had more assets.

However, in a scenario where the assets and liabilities are reversed—where Mr. Green has $44,200 in assets and $200 in debt and a positive $44,000 net worth, while Mr. Red has $86,100 of assets and $42,100 in debt—the individuals now felt that Mr. Green was in the better financial position.

In essence, participants tended to rate the low profile (low assets and low debt) as better off financially in positive net worth scenarios, but tended to rate the high profile (high assets and high debt) as better off financially in negative net worth scenarios. Or stated more simply, participants preferred less debt when net worth was positive, but more assets when net worth was negative.

Notably, in a follow-up experiment, the researchers found that the same preferences held across more detailed household balance sheets (e.g., broken out to include retirement accounts, real estate, student loans, mortgages, etc.), where again there was a preference for less debt when net worth was positive and more assets when net worth was negative.

Perceptions of Wealth and Decision-Making

In the second study, Sussman and Shafir examined how varying perceptions might influence actual financial behavior. Given the results of the first experiment, the researchers hypothesized that participants would be more inclined to indicate a preference to use debt when their net worth was negative, and more inclined to indicate a preference to liquidate assets for spending (rather than borrow) when their net worth was positive.

To examine this, the researchers again presented participants with two profiles of equivalent net worth but varying in the composition of the household balance sheet. In this case, participants were given a series of different items (television, motorcycle, work computer, and bathroom repairs) and asked to indicate in which of the financial profiles they would be most inclined to borrow or spend down assets. Regardless of the category presented, participants did indicate a preference to borrow to pay an expense when net worth was negative, and a preference to liquidate and spend from assets when net worth was positive.

In the second experiment within Study 2, participants were then asked to take on the role of a lender, and indicate which of two profiles (one “high” profile and one “low” profile, consistent with other experiments) that they perceived to be in a better financial position to receive a loan. Again, consistent with the prior experiments, participants indicated that when net worth was negative, they perceived the households with more assets to be in a better financial position, whereas when net worth was positive, the households with less debt were in the better financial position.

Financial Planning Implications

One of the key difficulties in trying to determine what to do with behavioral insights is determining whether a tendency is one which generally promotes good behavior (e.g., our reluctance to spend down retirement assets and preference to use cash in a checking account instead), or a tendency which can lead us astray. Of course, the reality is that behavioral tendencies can often do both, and are highly dependent on the specific context and circumstances of an individual’s situation. However, if we try to extrapolate from Sussman and Shafir’s findings, there are at least a few considerations to look out for when working with clients.

Shifting Preferences Across the Lifecycle

While Sussman and Shafir’s findings still need to be replicated, and further studies will hopefully provide greater insight into how preferences may (or may not) shift across the lifecycle, their findings would indicate that financial planners should be aware for the possibility of a preference reversal.

If human capital is not included on a household balance sheet (and, at least in practice, this seems to be rarely included), then many individuals (particularly those who seek a return on investment from an investment in higher education) will start out their career in their early 20s with a negative net worth. How long it takes to reach the point where net worth transitions from positive to negative will vary greatly from one individual to another (e.g., a physical therapy assistant with $10,000 in debt from earning a degree at a community college versus a doctor with $200,000 in student debt from medical school), but, if Sussman and Shafir’s findings hold among those early in the lifecycle, then we would anticipate those in their 20s with substantial student loans may actually prefer to take on even more debt when faced with circumstances which require either acquiring more debt or paying down assets, in order to preserve what little assets they have and maintain a “high” profile (even if it means adding high-interest credit card debt while holding cash in a low-interest checking account). However, once they reach the point that their net worth turns positive, they may want to pay down their debt and maintain a “low” profile instead.

Notably, for those who at least manage to “save” into long-term growth investments (e.g., a retirement account) while holding debt, the tendency is likely beneficial in the long-run, as the real growth opportunity from an aggressively allocated portfolio early in one’s career (with a long time horizon to weather volatility) is likely higher than the cost of borrowing. As a result, this tendency could be seen as a positive tendency, and financial planners may want to consider this when evaluating how they frame a client’s situation when presenting it to them. Though, of course, a risk of bankruptcy along the way still looms larger as long as they keep substantial debt in place as well.

Still, to the extent that some leverage on the personal balance sheet tends to help grow one’s assets (and ultimately net worth) in the long run, the real “risk” is that as net worth turns positive (and households become more interested in maintaining a “low” profile by paying down debt), it can lead to an excessive focus on paying down debt when prioritizing long-term investments would still be beneficial in the long run.

Example 1. Suppose an entry-level physical therapy assistant (PTA) earning $45,000 graduated at age 20 with a total of $10,000 in student debt. This PTA could easily be debt-free with a good paying job in their early 20s. Further suppose that this individual also buys a $125,000 home with a 5% down payment and an interest rate of 4% resulting in a total monthly mortgage payment of about $900. If this PTA experiences a preference reversal at this time, paying down a mortgage with a 4% interest rate may begin to look attractive. However, even after accounting for the higher ROI to paying down the mortgage due to factors such as PMI, just keeping the mortgage and investing into a stock portfolio using a tax-preferenced retirement account is likely a much better long-term wealth-building prospect for a typical individual in their early 20s.

Of course, this outcome is partially the result of the young age at which a PTA can reach a net worth of $0 by repaying a relatively modest student loan balance. The situation can look much different for people in different professions.

Example 2. Jeff is a 29-year old family practitioner who accumulated $200,000 in total student debt between undergraduate studies and medical school. His passion is serving rural communities, and, as a result, he earns a below average entry-level salary for family practitioners of $120,000. Even if Jeff makes his full loan payments on a 10-year amortization schedule and saves an additional 10% of his gross income (earning 8% per year), he won’t reach positive net worth territory until roughly age 36. If Jeff hopes to retire at age 60 and his preferences for more assets and less debt reverse at age 36 (i.e., he begins to prefer paying down debt more than increasing assets), then the preference to reduce the leverage on his personal balance sheet is less problematic, as Jeff would have had fewer years for leveraged returns before retirement anyway, and the shorter time horizon adds to the risk that the volatility might not smooth itself out before he’s ready to retire (especially since it’s less than 15 years before he enters the “retirement red-zone”).

Of course, even among physicians, not all will have the same dynamics as Jeff above. Some may start out earning more, leave med school with less debt, or otherwise have circumstances which result in reaching positive net worth at an early age, but regardless, the reality is that for those in careers which have long education and training requirements, a positive net worth will generally not be attained until an older age. All else being equal, this may reduce the concern associated with a sudden preference reversal between assets and debt, as aggressively paying down debt (to the detriment of accumulating assets which appreciate at a higher rate) is most concerning for young individuals with the longest time horizons.

Financial Fragility Concerns

While it was noted in the section above that a preference for more assets over less debt when net worth is negative could be seen as rational from the perspective of leveraging the household balance sheet to include more assets which can be expected to grow at a higher rate than the interest being paid on debt, the reality of leverage strategies is that they increase the variability of outcomes. Oftentimes this increased variability is on the upside, and thus leverage can increase wealth. But leverage also makes a household more vulnerable to financial shocks—as the reality is that leverage strategies work great… until they don’t.

Thus, a preference for increasing assets over paying down debt could, all else being equal, increase the likelihood that a financial shock (job loss, stock market crash, disability, etc.) will result in outcomes that can be devastating for a household, such as bankruptcy. Of course, the specific types of assets and debt accumulated can result in more or less risk to a household depending on the exact structure and terms of the debt. Although the risk may be even greater when households are accumulating assets that are not given stronger protections from bankruptcy in the first place, such as investment real estate and other private investments.

Example 3. Susan is a young surgeon who accumulated $200,000 in medical debt and started her first job with a salary of $300,000. While she maxed out her 401(k) contributions through her employer (a type of asset with greater bankruptcy protection than most), her interest in real estate and desire to accumulate a high level of assets has led her to prioritize building a real estate portfolio over paying down her student loans. With high income and easy access to credit, Susan has been able to highly leverage her real estate portfolio, taking on some speculative investments which could take a long time to pan out, if they ever do.

While Susan has potentially positioned herself to see tremendous growth in her wealth, she is also in a very fragile position. Should she get in an accident and lose the ability to practice as a surgeon, her balance sheet could collapse quickly as her current income may not be able to cover her debt payments, triggering her assets to be liquidated to cover as much of her liabilities as possible—potentially putting her in a much worse position than if she would have just focused on paying down debt and deleveraging her balance sheet. Of course, Susan can take steps to guard against some of these risks—such as purchasing disability, life, and other forms of insurance—but the reality is that she may not be able to perfectly protect against all of these risks, and she should acknowledge the increased financial fragility that comes from leveraging her balance sheet at a young age. Notably, that doesn’t mean she shouldn’t further leverage her household balance sheet, but she should understand the risks she is taking and have a plan to deal with them if an unfortunate sequence of events were to occur.

Another concern related to financial fragility may be an underinvestment inadequate insurance, as there is a risk that the desire to accumulate assets could also be tied to a general preference to maximize free cash flow (and limit ongoing spending “liabilities” like insurance premiums). Admittedly, this is reaching far beyond the findings of Sussman and Shafir, and additional research will hopefully give greater insight into questions like this in the future, but it’s possible that an overemphasis on asset accumulation while in the negative net worth domain could be associated with an overemphasis on free cash flow that also results in an underemphasis on other important financial considerations.

Confusing Client Communication

From a client communication perspective, it’s possible that the tendencies noted by Sussman and Shafir could explain some seemingly odd reversals in client preferences. If a financial planner finds themselves saying, “Mr. and Mrs. Client, we talked about this two years ago and you said you wanted to save more into your retirement accounts instead of paying down debt, why the sudden change?”, it may be possible that the sudden change is the result of a new emphasis now that they have a positive net worth (or more generally, a different perception of their financial position).

As some of the scenarios above illustrate, this is neither inherently good nor bad, but as any advisor who has been confused by changing preferences of clients can attest, it be confusing. Acknowledging that seemingly irrelevant factors such as one’s net worth going from negative to positive could result in changing preferences could help advisors better emphasize with clients and be prepared for shifts that may occur. More generally, it seems that a focus on a client’s assets—particularly for those who have accumulated a substantial positive net worth—may be especially likely to make them want to pay down debt (e.g., the retiree who decides they would like to eliminate their mortgage once they realize they have sufficient positive net worth to retire).

Advisors may also want to consider how the framing of their financial plans and other client communication could influence behavior. Presenting just assets, just liabilities, or a comprehensive picture of both could prime clients to behave in different ways. For instance, if a planner’s projections indicate that the best path forward for a client is to pay down debt, then a planner may want to consider how the way the plan is illustrated to a client may influences their likelihood of adopting such a recommendation. If the client has a negative net worth, it may be more beneficial to acknowledge that the client has “enough” financial assets for now, and it’s time to pay down the debt. Alternatively, if the client has a positive net worth, then presenting the full balance sheet—to reflect their already-strong financial position—may be an effective way to motivate clients to pay down debt (to achieve a “lower” profile).

Of course, it should always be noted that general tendencies which may apply to some, do not necessarily apply to all. Clients should always be viewed as the individuals that they are—full of unique idiosyncrasies. Nonetheless, the behavioral tendencies we observe can often serve as reasonable initial beliefs, and we can always update those beliefs in accordance with new evidence that we receive.

The key point of this discussion, though, is simply to acknowledge that seemingly irrelevant factors such as a household’s net worth can ultimately influence how they perceive their financial situation, the decisions they make as a result, and their willingness to keep accumulating assets (while not paying down the debt) versus liquidating assets to reduce their debt profile as well.

While much more research is needed, the early evidence suggests that households do perceive assets and debts differently depending on whether their net worth is positive or negative. As a result, different households may exhibit a confusing variability in their willingness to maintain debt (or not), and even present a reversal in preferences as their net worth moves from negative to positive territory. Ultimately, such preferences and the tendencies that result could have both positive and negative influences on household decision making. But it’s nonetheless important to understand the factors which may be lurking in the background and influencing client behavior!

So what do you think? Do you think households perceive assets and debts differently based on their net worth? Have you seen clients reverse their preferences for accumulating assets and paying down debt as their net worth shifts from negative to positive? What implications do such preferences and tendencies have for working with clients? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!