Executive Summary

A considerable challenge for financial advisors providing standalone fee-for-service financial planning advice is figuring out the "right" price that is both profitable to the advisor, and attractive to consumers. Notably, this is a challenge that largely did not apply to past generations of advisors, who typically either just sold products with commissions (that were determined by product manufacturers and not chosen by the advisor anyway), or charged an AUM fee (in which there was strong convergence on the 1% price point for all advisors). As a result, fee-for-service advisors who are aiming to reach clients through a different compensation model have both an opportunity to expand service into previously unserved markets (particularly those prospective clients who cannot be reached through traditional advisor business models like commissions or AUM), but also a challenge in needing to take more responsibility for determining how to price their services in the first place.

In this guest post, Alan Moore of XY Planning Network and AdvicePay, shares his thoughts on how to profitably price a fee-for-service financial planning offering, including the options for calculating financial planning fees (e.g., flat fee, hourly, project-based, percentage of net worth and income), the structure of paying advice fees (e.g., one-time fees, ongoing fees, or a combination), setting the right advice fee frequency (e.g., monthly, quarterly, semi-annual, annual), how to integrate some combination of fee-for-service and AUM fees (for firms that are looking to transition from an existing AUM model), how to make sure your fees are both profitable for the advisor and reasonable for your (niche) clientele!

Ultimately, though, the key point is to acknowledge that like the massive shift from commissions to AUM over the past few decades – which allowed advisors to serve clients in a fundamentally different way and reduced certain conflicts of interest – the opportunity to provide fee-for-service financial planning allows advisors to continue to evolve their business models, profitably serving an ever-increasing range of clients with fewer conflicts of interest. Yet the freedom and flexibility of the fee-for-service model does present new challenges in setting an advisory firm's fees in the first place... even as advisors with a fee-for-service financial planning model are poised for success in serving the next generation of clients (who are eager to receive real financial advice, but want to pay for it directly!)!

The Evolution Of Advisor Compensation

The way financial advisors charge clients for their advice services has evolved over the history of the financial services industry. In the past, advisors were functionally salespeople, who were paid commissions for any products sold. At that time, the ultimate goal of financial planning was to better understand a client’s needs, so that you could effectively sell them a product, and be compensated for the advice via its implementation using the company’s products.

Over the past 20 years, this model has been giving way to the assets under management (AUM) model, which allowed advisors to charge a fee without having to actually sell a product. Instead, they were “selling” asset allocation and portfolio management services, and more importantly (from the business perspective) an ongoing relationship with the clients whose money they managed. In this model, the compensation for advice was the ability to attract assets to manage pursuant to the advice, and deepening the client relationship to retain those assets (and the AUM fees the clients paid).

While the AUM model began to shift the focus from products and sales to ongoing advice and relationships (albeit pursuant to attracting and retaining assets), it nonetheless marked the first step towards “fee-for-service” financial planning, where the client “pays” for the advice (as opposed to solely being compensated by product sales). The caveat, however, is that by charging based on assets being managed, only a small percentage of Americans were able to engage such AUM-based advisors, as the model necessitates clients both having liquid assets available to manage, in sufficient amounts, and to be inclined to delegate management to an advisor in the first place… which is estimated to be no more than approximately 7% of Americans. Advisors charging AUM therefore miss out on a large portion of the population who might be interested in and have the financial wherewithal to pay for financial advice, but simply can’t access it via a minimum-managed-assets model.

Today, financial planning is further evolving to an advice-centric, relationship-focused practice, independent of either the products to be implemented or the assets to be managed. However, the way that advisors charge for such financial advice requires serious contemplation – a phenomenon that wasn’t necessary in a product-based sales world (because the commissions were set by the company), and was less challenging in an AUM world (where the 1% AUM fee is so ubiquitous), but creates serious challenges for purely fee-for-service “advice-only” advisors trying to sell a purely intangible service like financial planning. Simply put, “advice” is challenging to accurately value and price.

Nonetheless, the appeal of the fee-for-service model is that it introduces a new way for advisors to structure their businesses, making it possible to profitably serve a wider range of clientele – especially younger clients who don't necessarily have large portfolios but may be happy to pay for financial advice directly from their income. With this shift, Americans who haven’t previously had access to financial advisors due to financial (i.e., asset or product) constraints are now able to make that advice connection.

In fact, the trend is already underway. While asset-based fees remain the dominant fee structure, according to Cerulli the number of advisors charging fixed fees for financial planning continues to rise, increasing from 33% in 2013 to nearly 50% in 2017. Industry-wide, revenue from financial planning fees is expected to increase 25% (from 4% to 5% of total industry revenues) this year alone. This change tracks a shifting paradigm that opens a new realm of possibilities to both advisors and clients who may not have otherwise had the opportunity to work together in an advice relationship.

And notably, the trend appears to be accelerating with the generational rotation of financial advisors themselves. While roughly 36% of all advisors of all ages are charging a fixed fee for financial planning, a staggering 62% of millennial advisors are using a fee-for-service model. In essence, it appears that as younger generations become increasingly willing to pay for financial advisors, younger advisors are rising to the occasion to serve their peers through the fee-for-service model.

This win-win scenario has many advisors reevaluating their service model and wondering how they can incorporate fee-for-service billing into their businesses. In fact, the most commonly asked questions we hear at AdvicePay (a compliant payment processing platform for financial planning fees) when advisors launch a fee-for-service model all revolve around fees, how to integrate them into an existing firm, and/or how to set them for new clients going forward.

So how can you develop, implement, and run a fee-for-service model for your financial planning firm and profitably serve traditionally neglected clients without needing to “give away” financial advice for free to get paid by other means?

Options To Calculate Financial Planning Fees

For the purposes of this article, we will define “Fee-for-service billing” as way of charging fees for financial advice that is not contingent on product sales (i.e., commissions) or “also” managing a portfolio (AUM-based). Or viewed another way, when looking at how advisors are paid, if you take away commissions and take away investment management fees on AUM, the compensation you’re left with is fee-for-service billing.

The innovative ways in which fee-for-service advisors structure those advice fees vary widely and depend on many factors, including the target market of clientele (and what they can or are willing/able to pay), as well as the business goals and income desires of the financial advisor themselves (and what they’re trying to achieve).

That being said, here are a few of the most common ways to structure your fee calculation:

Flat fee. With the flat fee calculation option, you determine a fee that’s appropriate for the services you plan to provide to your clients, and charge that fee to all your clients throughout the year for providing that service. With a pure flat-fee model, services typically do not vary appreciably between clients, so charging the same amount to all clients works because the whole point is that they all receive the same (appropriately-priced) service. This structure works best for advisors with a clearly defined niche or other target market, where a standardized fee for a standardized service model can make sense for both the advisor and their clients and should be relatively easy to determine.

Tiered fee based on (tiered) services. With the tiered fee option, clients are charged fees at varying tiers depending on the depth of services rendered. Typically, the services at each tier are defined in advance, and the pricing for each tier is set at a level where those services can be delivered profitably; prospective clients then pick from the ‘menu’ of service tiers based on what’s an appropriate fit for them. For example, younger, less wealthy clients with fewer assets pay a basic flat fee to cover their core financial advice needs; as their assets grow and become more complex and they require additional services, they graduate to a higher fee tier, which has additional services included as well. Essentially, fees scale with a client’s increasing financial advice and service needs, and services are segmented for clients in each fee tier.

Hourly (time-based) fee. This fee calculation option is pretty self-explanatory: advisors simply charge for the hours actually spent working with a client. Working hourly allows advisors to work with clients regardless of their (available) assets, as long as they have some means of paying. An added benefit, relative to most other advisor business models, is that hourly fees provide immediate revenue, as most advisors assess the fee “on the spot” at the end of the meeting (as opposed to a commission-based model where the advisor isn’t compensated until the product is sold and implemented and the commission is paid, or the AUM model where the first AUM fee may not come for several months after the relationship starts until the next quarter fee is assessed).

The hourly fee structure was popularized by Sheryl Garrett, founder of the Garrett Planning Network, in the early 2000s as a way of doing fee-for-service financial planning and thinking about financial planning fees through a non-AUM lens. Yet while the introduction of the hourly fee represented a critical step towards profitable fee-for-service financial planning, the caveat is that there are still only very few sizable hourly-fee firms that have managed to successfully scale the hourly model.

Project-based fee. Whereas an hourly fee structure charges based solely on number of hours spent working overtime with a client, project-based fees are set (and quoted up front) based on either a cumulative estimate of the time to complete the project for the client (working backwards from the value of an hour of the advisor’s time), or based on the perceived value of the project for the client (and what the time is worth to the client). The biggest appeal of project-based fees is the opportunity to set a more holistic price based on the holistic value of the service being provided (rather than “just” based on the hours spent working), though in practice that still requires the advisor to be effective at communicating the value of their holistic advice.

Alternatively, like time-based fees, project-based fees can also be offered for more modular planning components, making financial planning accessible to prospective clients who have just a few questions and who might not be ready for the full financial planning package.

Input Options To Set The Right Financial Planning Fee

When determining an advisory fee structure, there are many options from which to choose. The good news is that this means the advisor can structure fees in a way that works best for that individual advisor; the bad news is that it’s often difficult to decide on a structure in the first place because there are so many options – the infamous “paradox of choice” problem? And even once you choose which approach – flat-fee, tiered fees, hourly (time-based) fees, or project-based fees – it’s still necessary to set the actual level of the fees, commensurate with both what the advisor needs to earn to be profitable, and what the client will pay for the services provided.

In practice, regardless of the particular type of fee-for-service model, most financial advisors set their fees based on one of four fundamental approaches:

Fixed fee based on the advisor’s time. Whether it’s charging hourly for the advice itself, a project-based fee, or a flat fee (or multiple fee tiers), many financial advisors set their fees based on what an hour of their time is worth to them. In essence, the process of setting the fee starts with the targeted value of the advisor’s time – e.g., if the advisor wants to generate $150,000 of revenue, and can realistically have 1,200 hours of client-facing (i.e., billable) time, the time-based fee must be at least $125/hour, while if the advisor wants to generate $200,000 of revenue but can only manage 1,000 billable hours, the time-based fee must be at least $200/hour. Thus, if the flat fee service will take 20 hours, it’s priced at $2,500 or $4,000, respectively, while a 30 hour/year service tier would be priced at $3,750 or $6,000, and/or the advisor might simply bill at a $125/hour or $200/hour rate.

Fixed fee based on client value. The more targeted the advisor is to a particular type of ideal/niche clientele, the easier it is to base the fee specifically on the perceived value of the service to the client. The advisor who works primarily with business executives who value their own time at $1,000+/hour might be able to easily charge $500/hour, based not on the value of the time to the advisor but the value of the time (savings) to the client. More generally, to the extent that the advisor really knows his/her ideal client profile, and fully understands the complexity and issues associated with that ideal client, the more feasible it is to base the fee on the perceive value to that particular niche clientele. As an added benefit, a clearly defined niche or other target clientele also typically have a fairly consistent level of net worth or average household income, which ensure the advisor can set a fee that makes sense both for clients’ wallets and the advisor’s bottom line.

Net worth plus income. Another approach to setting advisory fees is simply based on the client’s financial wherewithal to pay in the first place. The AUM fee naturally works in part because the fee is always “affordable” relative to the assets being managed (since it is literally calculated as a percentage of those assets); similarly, the “net-worth-plus-income” fee is calculated based on the client’s overall income and net worth (but regardless of “investable assets” in particular). For instance, the advice fee might be 0.5% of net worth plus 1% of adjusted gross income (AGI). Although this option is not common, it is gaining some popularity, and many advisors gravitate towards it because net worth helps eliminate some of the conflicts of interest that AUM billing is known for, like the decision of whether to pay off a mortgage or save money for retirement (where paying off the mortgage impairs the fee of an AUM advisor, but has no impact on a net-worth-plus-income fee, as the net worth calculation doesn’t favor paying down debt or saving for retirement because in the end, the balance sheet is the same).

Notably, adding the income component of the net-worth-and-income fee (as opposed to “just” a net worth fee) provides more flexibility to work with a wider range of clients… in particular, those who may have high debt but also have high income (e.g. doctors) and want to pay for financial advice.

Complexity. The complexity input option charges clients based on how “complex” their financial situation is. Typically, it is used as a proxy for a time-based fee, recognizing that it’s often impossible to perfectly estimate the amount of time the plan will take (and often difficult to defend if the client asks why it can’t be done faster), while it may be easier for many advisors to simply set the fee based on agreed-upon “complexity factors”.

Of course, complexity comes in many different forms. In a recent XY Planning Network review of various complexity measures used by its advisors, we found hundreds of data points that can be entered into a complexity calculation, ranging from things like whether or not your client is a business owner, or has a spouse or children, or what life cycle they are in from accumulator to retiree. Thus, the challenge of setting a formula based on complexity is that the range of possible complexities can be quite cumbersome, but it does allow the advisor to hone in on how to charge clients based on their complex needs and goals, and for those advisors with a clear target clientele, a common set of complexity issues tends to emerge (making it easier to price those complexities consistently).

Structure The Required Payment of Advice Fees

Once you’ve determined the right fee methodology and relevant input options to set those fees, the advisor still needs to decide how to actually charge the client.

There are two primary means of charging clients: the upfront, one-time fee for the development of a financial plan, and an ongoing fee for continued financial planning services (monitoring and implementation of the original advice, and ongoing advice for new planning issues that may arise).

Upfront one-time fee. Developing an initial financial plan is extremely time consuming for both the client and the advisor. Going through the data gathering phase, defining financial goals, developing the plan, and creating and implementing the plan, all contribute to the time it takes to go through the initial planning process. And because the time it takes to do the upfront planning is greater, an upfront (one-time) planning fees helps to ensure that the advisor is compensated for that substantial upfront time investment with the client.

Ongoing (Subscription or Retainer) fee. The purpose of either a subscription or retainer model is for advisors to charge an ongoing fee for ongoing services. Functionally, the difference between an ongoing subscription and ongoing retainer fee is that retainer agreements tend to be open-ended (where a substantial part of what clients pay for is “access” to the financial advisor as needed), while subscription agreements have a set series of routine meetings, interactions, and other service commitments (and the relative significance of the “access” component is lessened).

Combination. The most common fee structure for most fee-for-service advisors is a combination of both a one-time fee and ongoing fee payments. This fee structure gives separate and rightful value to both the initial financial plan and the ongoing relationship, and helps clients understand the difference between and value of the two services.

Advisors who only charge a subscription fee often struggle to get buy-in from clients as charging an upfront fee is a good way to either screen out clients who aren’t really committed and therefore will pass if there’s an upfront fee, and/or will gain client commitment as once the client has “written a check” they are immediately invested in the financial planning process and are often much more willing to schedule meetings and begin the process because they have already committed their money.

Conversely, advisors who only charge a one-time fee often struggle to grow and scale their businesses, simply because when engagements are more one-time and transactional, it requires a very large number of clients to gain critical mass, which is beyond the marketing capabilities of many/most solo fee-for-service advisors.

Real-Time Planning/Quickstart Offering: In recent years, there has also been an uptick in shorter, real-time planning sessions, often called “Quickstart” programs. Quickstart offerings are typically a one to two hour meeting with a client that covers one or two primary topics, at a lower (and fixed) cost for the time of the meeting. This is still a one-time planning arrangement, but it’s tailored for the client who can’t afford a full comprehensive (multi-thousand-dollar) financial plan.

Quickstart offerings are a great way to “get paid to market” the advisor’s services, since financial planning can be so hard to define and explain, but once a client goes through the process – even just for a specific modular component – they will better understand and appreciate what the advisor does for clients.

Setting The Right Advice Fee Frequency

“How often should I charge clients?” This is a very common and very important question, especially when charging ongoing fees, where advisors may bill monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, or annually. Charging a fee “too frequently” can make clients feel nickel-and-dimed, and may stress the relationship if the client feels they’re being charged more often than they’re actually receiving value from the advisor; on the other hand, charging “too infrequently” will make each fee larger when it occurs, potentially causing “sticker shock” for the client.

Monthly. Monthly billing is considered the “Netflix” model of financial planning, and is most common for clients paying their advice fees directly out of their (typically monthly) cash flow. The virtue of the model is that, instead of paying a one-time fee whenever a service is needed, or a large (and erratic, and potentially-cash-flow-disruptive) annual fee, clients get into the habit of paying an affordable fixed fee on a regular basis, just like any other monthly bill.

Quarterly. Quarterly billing makes more sense than monthly billing if fees (and services) may vary from month to month, and/or if services are structured on a quarterly basis. Quarterly billing is also a good option for clients who plan to pay that quarterly fee out of an investment brokerage account, which often isn’t practice to be tapped into monthly (as it may necessitate more frequent trading to free up available cash for a monthly fee). Historically, quarterly billing has been very popular under an AUM model as well.

Annual. Annual billing is often an appealing way to wrap together a comprehensive set of annual services. However, in practice annual fees are often problematic, both because the sheer size of the fee when paid all at once may incur sticker shock (or an outright cash flow squeeze) for some clients, and also because advisors who accept more than $500 more than six months in advance for financial planning services are deemed to have “custody” under existing SEC guidance. Thus, for instance, collecting $2,000 at the beginning of the year for all services to be rendered throughout the course of the year will trigger custody.

Some firms attempt to get around the custody rule by charging $1,000 at the beginning of the year, claiming that technically, no more than $500 of the fee is actually being paid more than six months in advance; however, the SEC has never issued guidance to affirm this approach, and it isn’t feasible for those who plan to charge more than $1,000/year anyway.

Semi-annual. Semi-annual billing has been a fallback for advisors shifting away from an annual relationship, either in an attempt to meet more regularly with clients to provide more ongoing value, or simply to avoid the challenges of annual billing (and the custody it may trigger) as a semi-annual fee will by definition never be assessed more than 6 months in advance (avoiding the custody issue altogether).

Integrating Fee-For-Service And AUM Fees

While the fee-for-service model has gained popularity over the past few years, with many advisors moving away from investment management and focusing exclusively on comprehensive financial planning, most advisors retain at least some investment management services (and charge some AUM fees) as well. So, how do they charge for investment management under a fee-for-service model, or integrate fee-for-service planning into an existing AUM model?

Subscription-based fee plus AUM. For advisors who treat (or want to start to treat) their financial planning services as being separate from their investment management services, the most straightforward approach is simply to treat them as two separate services with separate full-price fees for each. For some advisors, it’s appealing to have clients pay separately for financial planning and investment management services as a means to force them to value the services separately.

Reduced subscription-based fee plus AUM. It can be argued that there is some overlap in providing both investment management and financial planning services, so when they’re combined, the combined work for both is less than the cumulative work of doing each separately. This overlap in services can justify a reduction in fees. Accordingly, some firms set a lower minimum planning fee – less than what they would charge on a standalone basis, but enough to reflect the additional financial planning value being added above and beyond the AUM fee (and especially for clients with smaller accounts where the AUM fee alone isn’t sufficient to compensate the advisor for the total effort).

Subscription-based fee plus reduced AUM. For more planning-centric advisors, where the financial planning advice is the “primary” service and the investment management is just an “add-on” for clients who also want implementation help, an alternative approach is to charge “full” subscription-based planning fees, but a reduced AUM fee (e.g., just 0.50% to 0.75%) for the complementary investment-only portion of the services.

Financial planning fee turned AUM fee. Some firms charge a financial planning fee until a client reaches a certain asset level, at which point an AUM fee is imposed in place of the financial planning fee. For instance, the advisor charges $3,600/year for financial planning and any investment management services, until the client reaches $360,000 of AUM, at which point the client pays 1% of AUM going forward. This approach is most commonly seen in advisory firms that have historically charged 1% of AUM but that want to add a planning fee for their smaller clients to ensure a minimum level of revenue per client, either because they are not making as much money working with clients who do not meet their asset minimums, or to be able to engage new clients (e.g., children of their current clients, or to give their younger advisors the opportunity to work with their peers). The virtue of the AUM-with-planning-fee-minimum approach is that for firms already focused on the AUM model, it’s a means to charge some sort of planning fee without undermining the AUM fee structure they have in place.

Flat fee that includes investment management. Some firms simply charge a flat fee for financial planning that includes investment management as part of the service. The thought is that advisors charge clients enough to be compensated for a comprehensive service, and simply detach from the AUM fee altogether (especially since the amount of time it takes to service the client may be the same regardless of their assets). Although this approach does work, and actually allows for a much simpler way of charging fees, some advisors express concern around whether or not the advisor is taking on additional risk by providing investment management services without being “properly” compensated (and more generally, the advisor doesn’t have any incentive to create portfolio growth, either, which may be a concern for some clients).

How Much Should An Advisor Charge?

Understanding how exactly the advisor should charge clients, and how often, are important steps of determining your fee structure. Perhaps the crux of the equation, though, is determining just how much the advisor needs to charge for services, as setting the acutal fee level is what directly dictates the advisor’s (maximum) revenue.

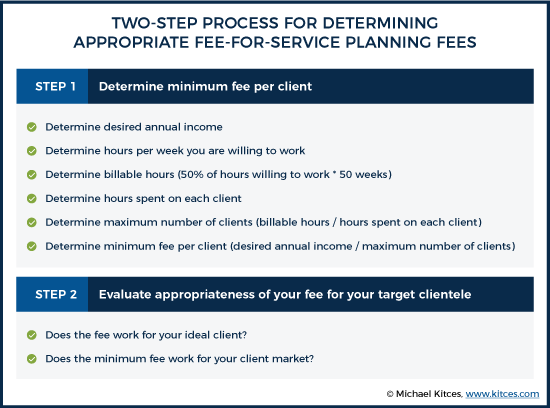

Figuring out what financial planning fees are appropriate for clients is a two-step process:

Step 1. The advisor should ask themselves how much they want to make per year (recognizing that gross revenue must be even higher to account for the impact of expenses like overhead, staffing, technology, office space, and employee benefits). For most, it’s easiest to work backwards from how much the advisor wants to make net, adding in any expenses.

Next, ask how many hours per week you’re willing to work. Do you want to work 20 hours/week because you want a lifestyle practice that provides a lot of flexibility? Or are you willing to work 45 hours/week to build a financial planning enterprise? (Ultimately, I never advocate for working more than 45 hours/week to ensure you maintain a healthy work/life balance.)

Once there’s a target for the number of hours per week that will be worked, multiply by 50%; this provides an estimate of the number of hours the advisor can actually bill per week (given that not all hours worked will be client-facing and/or otherwise billable to clients). Take that number and multiply by 50, which is an estimate of the number of weeks that you will work per year after two weeks of vacation. Of course, you can adjust this formula based on your lifestyle goals and the kind of business you want to build; others might only include 45 weeks or even fewer, if the goal is to take more vacations.

Now, consider about how many hours the advisor will spend with each client, including both hours actually spent in meetings with clients, and hours spent doing supporting client work. Bear in mind that advisors tend to spend more time with newer clients than existing clients, so be sure to factor this into the equation. For example, the assumption might be 30 hours with a client in their first year (this includes time spent gathering data, setting goals, delivering the financial plan, etc.…) and only 10 hours/year thereafter.

Now do the math. For example, if you want to make $200,000/year working 45 hours/week (1,012 hours/year spent on clients), and you have a 100-client maximum you can work with, it means you need to charge at least $2,000/year/client to achieve your desired income.

If your firm is still growing and you haven’t hit that 100-client maximum yet, keep that $200,000/year goal in mind and set your initial ongoing fees accordingly so you don’t underprice your services. For example, if you bring on 18 new clients/year (1.5 clients/month), you’ll be providing 540 hours of service to those new clients throughout the year, which means you only have time for 47 existing clients. Those 47 existing clients will only bring in $94,000 (versus your income goal of $200,000) in revenue, which means you need to charge those 18 new clients an initial planning fee that helps compensate for the difference. Of course you need to charge an initial planning fee that makes sense compared to your ongoing service fee; if you charge $2,000/year for ongoing services, it would be hard to justify a $5,000 initial planning fee on top. But if you charge $2,000 for the initial financial plan, for example, your revenue increases to $130,000/year, and as those 18 new clients become ongoing clients, your revenue continues to climb towards that $200,000/year goal.

Step 2. Compare the ideal fee that will allow you to accomplish your financial goals with your ideal client profile; is your fee in their comfort zone?

Anecdotally, advisors using a fee-for-service model appear to be charging between 1%-2% of their clients’ incomes (i.e., this is the zone where clients are typically comfortable). Advisors who are charging less than 1% of their typical client’s income may be charging too little (or at least, should have room to offer a more value-added service and accordingly charge clients more for it). Conversely, advisors offering services that will cost more than 2% of the target client’s income on average may experience a lot of pushback from clients when comparing value to fees. That’s not to say that advisors can’t charge more; one advisor in Brazil charges as much as 5% of income and has grown a very successful firm! The 1%-2%-of-income recommendation is simply a rule-of-thumb to helps advisors hone in on an ideal fee that will be palatable to their clients.

Compare how the perspective shifts when working with clients with average household incomes of $100,000/year versus $300,000/year. The $2,000/year fee from the example above represents 2% of a $100,000/year household income and is therefore on the upper end of that 1%-2% range. On the other hand, a $2,000/year fee is less than 1% of a $300,000/year household income, in which case the advisor might consider raising the fee to a more “appropriate” $4,500/year.

Ultimately, if the minimum fee and the client market with which the advisor wants to work don’t match, it’s necessary to either re-evaluate your income desires, or shift your ideal client profile to work with clients who can afford a higher fee that will allow you to meet your financial goals.

Knowing Your Target Clientele (And Finding Your Niche)

Figuring out the logistics of how, what, and when you should charge your clients can be overwhelming because there are so many choices and few actual recommendations. That’s because the perfect fee structure for all clients doesn’t exist. However, the ideal fee structure for your particular target clientele (e.g., your niche market) does.

Throughout most of the history of financial planning, just being a financial planner was a niche. As the number of financial planners has grown over the past two decades, though, simply being a financial planner—even a really good one—is no longer enough to differentiate. Which matters, because trying to out-market a firm 100 times larger while offering the same service is an uphill battle, and one the smaller advisor is unlikely to win. But find your focus and you’ve found your secret weapon. You can get your fill of great clients, serve them profitably, and build a successful business.

When determining your target clientele, the narrower the niche market, the better. “Individuals and families,” “young professionals,” “women,” and “business owners” are all too broad of categories to set an appropriate fee structure (because they won’t have a consistent income level, net worth, or overall affluent). If you can’t determine the average financial wherewithal of your clients to figure out what to charge, then you need to more closely define your niche.

Many advisors fear that by focusing too narrowly on a niche, they will consequently narrow their base of potential clients to a point that limits growth. The truth, though, is that while casting the net wider may lead to more prospects, it often leads to fewer actual clients, because the advisor isn’t actually meaningfully differentiated to any of them. In other words, advisors who are too broadly focused consistently end out losing clients to other advisors who are each more specialized in that particular client’s needs and issues (and therefore better suited to meet the needs of that particular client).

Conflicts of Interest In Advisory Fee Models

All advisory fee structures come with some conflicts of interest, but it’s important to try to define you’re an advisory fee structure that mitigates those conflicts to the extent possible for the intended clientele. And while it’s generally not feasible to eliminate all conflicts of interest, knowing your niche and defining a fee structure around that niche certainly helps you better navigate potential tensions.

For example, say “young doctors” comprise the majority of your client roster. Young doctors generally have very high income but also very high debt, so you might consider a net worth or a flat fee structure to eliminate the advice conflicts between paying down debt and saving for retirement.

Another example niche is working with service members in the military. You could use a tiered monthly fee structure that is tied to their own pay grades. For instance, you might charge an O-1 lieutenant in the army $50/month, and then raise that fee to $90/month when they’re promoted to O-2. There’s somewhat of an immediate buy-in when a service member sees a fee structure based on their pay grade. Right away, they’ll see you as someone who understands their specific financial needs. Conversely, this fee structure will obviously not resonate with someone who is not in the military, and that’s perfectly okay—part of the reason your fee structure attracts the right clients is that it also repels the wrong ones.

Ultimately, your service model and fee structure should be based on your niche. The only way to narrow the overwhelming list of options for charging clients is to know exactly whom you’re going to serve.

Compliance Considerations In Fee-For-Service Financial Planning

Unfortunately, confusion about the value proposition that financial advisors provide isn’t unique to consumers; as more advisors adopt fee-for-service financial planning models, regulators are trying to catch up as well. Which creates unique new tensions, because historically, financial advisor regulators were mandated to oversee product sales (FINRA) or investment management services (the SEC and state securities regulators), but over time, they’ve been cornered into regulating financial advisors who give financial planning advice. This has complicated compliance considerations, with different rules and expectations coming from different regulators.

For instance, some regulators have asked that advisors stop using the term “retainer” because “monthly retainer” or “quarterly retainer” resembles more of an attorney-like fee where a client puts money in escrow and an hourly rate is billed against that money held on retainer (and it’s important to ensure that “unearned” fees are refunded back to the client if the relationship terminates). In reality, most advisors aren’t charging an hourly rate with a retainer, but rather a flat fee billed on a set schedule like a subscription (e.g. monthly or quarterly). Accordingly, it’s important to be clear about whether the advisor is actually using a subscription fee model, versus really charging a “true” retainer where fees are paid in advance even if they haven’t yet been (and may never be) earned.

Additionally, some state regulators have expressed concern about whether some fee models may constitute “unethical business practices” (or at least could, depending on whether/how advisors choose someday to abuse them). For example, Utah has banned any fees where clients are charged based on their ability to pay rather than the services rendered, claiming that an hour of the advisor’s time should have the same cost (regardless of whether it’s more valuable to one client than another). Consequently, advisors in Utah are not permitted to charge income- or net worth-based fees, nor complexity-based fees. Utah has also capped hourly fees at $150/hour, so advisors in Utah may instead consider a flat fee based on a niche instead.

Other states like Illinois and Nevada are denying advisors from registering using a blended fee structure of monthly financial planning plus AUM, insisting instead that advisors must bundled both services together and cannot offer clients a choice (and/or that if a choice is offered, the fees must be reduced to recognize the overlap).

The key takeaway: consult with your state compliance regulator, and/or compliance consultant, to determine which particular types of fee-for-service models your state will and will not allow.

Charging For Fee-For-Service Financial Planning with Confidence

Most advisors tend to undercharge when they first launch their firms and price the value of their advice. In XY Planning Network’s first ever Benchmarking Survey in 2017, a whopping 100% of XYPN advisors using a monthly-fee-for-service structure had raised their fees over their first three years in business from the levels they were undercharging to begin with.

In some cases, it’s simply because when they first launched, they hadn’t defined their niche and as a result, didn’t know that 1%-2% of income figure upon which to base their fee. In other cases, it’s more likely a lack of confidence in delivering the financial plan, or a general lack of confidence in “selling” the value financial planning (as contrasted with selling products, which are more straightforward, because it’s “easy” to sell the features and benefits of a specific product). Unfortunately, though, fee-for-service financial planning is both more nebulous (the intangible value of advice), and more transparent (which is good for consumers, but putting transparent your fees in front of the client also gives them more room to question whether or not your financial advice is worth the cost!).

Building out an annual service calendar helps better demonstrate the advisor’s value to clients, and can help build confidence in the service being provided. This calendar shows clients everything the advisor will do for them throughout the year, from webinars and newsletters to investment and insurance reviews. Packaging all of these together to “productize” and presenting a year’s worth of work with a single price tag also helps clients think in terms of annual service (and establish a cumulative value), versus monthly or quarterly service (which is important to avoid the unrealistic expectation that a monthly fee means the advisor and client will interact monthly).

Similarly, selling the value of financial planning as an annual fee (paid incrementally throughout the year to make it easier to incorporate into the client’s cash flow) also reduces the risk that if you bill financial planning as a monthly service and you do not provide a service any given month, regulators may ask you to refund your client for the unearned month of fees.

Raising Financial Planning Fees Over Time

Because the cost of doing business tends to rise every year (from staff raises to investments in technology), most businesses – including financial advisors – need to have a plan to raise fees every year.

Under an AUM model, revenue per client increases every year (at least on average) as markets go up (and as clients save money and contribute to accounts), making it easier for the business to handle increased costs. This doesn’t happen organically with the fee-for-service model, though. And while the advisor may be happy netting $100,000 (or $150,000, or some other number) today, that $100,000 today will not be worth $100,000 in 10 years thanks to inflation – eroding both the ability of the business to cover its ever-increasing costs, and for the advisor to maintain their own standard of living over time.

For this reason, it’s especially crucial under a fee-for-service model to get clients into the habit of paying an additional 3%-5% every year. Ideally, advisors can even work the increase into the financial planning agreement itself, so that the fee increases “automatically” under the existing agreement. And bear in mind, for most clients, it’s much easier to accept a fee increase of 3% every year, than 12%, 15%, or even 20% every five years (which is a heck of a hit to take all at once!). Simply put, standardizing fee increases (in small and manageable bites) better habituates clients and eases the blow of a bigger bill.

Getting Paid For Real Financial Planning

Nearly three decades ago, the first AUM-fee-based advisors came onto the scene. This was a massive shift – driven largely by advancements in technology and products – from the door-to-door insurance agents and stockbrokers who at the time dominated the financial services industry. Eventually, these AUM-based advisors gave rise to today’s fee-for-service financial advisors who are able to provide more comprehensive financial advice with fewer inherent conflicts of interest, allowing them to act in the best interests of their clients, and with a model that serves an ever-increasing range of clients, opening the door to younger generations of clients who are just as willing to pay for financial advice if offered at a price they can afford.

I truly believe in the value of real financial planning, and the value of the advisor-client relationship. Adopting a fee-for-service financial planning model allows advisors to profitably serve a wider breadth of clients who historically have not had access to financial planning. As the financial planning landscape continues to change, fee-for-service advisors are poised for success, ready to serve the next generation of clients hungry for real financial advice. Adopting a fee-for-service business model allows advisors to position their firms for the future of our industry, help attract and retain next-generation talent, and ultimately increase the value of the business by lowering the average age and adding a substantial number of accumulators to their client base.

So what do you think? How do you set fees and ensure that they are profitable? What are your favorite methods of charging clients for fee-for-service planning? How do you think fee-for-service compensation will evolve in the future? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Where did you find that Utah limited hourly rates to $150/hour? Can you provide a source from the state? Please and thank you!