Executive Summary

Benchmarking the results of an investment manager is a basic form of accountability that helps to determine whether the manager is really adding value with their investment process. For which the evolution in recent decades of ever-more-finely-sliced benchmarks – from the Morningstar Style Box to factor regression analysis – applies an ever-increasing focus on determining exactly which managers are really adding value, and which are simply benefitting from the underlying results of a well-performing asset class (or factor) they happened to already own.

Of course, benchmarking has a dark side as well. For underperforming managers, it can literally cause them to be fired – arguably for a justified reason of underperformance, but an outcome that incentivizes at least some managers (including some financial advisors who manage portfolios) to become closet indexers… while others are always in search of alternative “benchmarks” that are less prone to (potentially) unfavorable outcomes in the first place.

In this context, a recent “innovation” suggested by some advisors and managers is to benchmark results relative to the investor’s (financial planning) goals in the first place, rather than the manager’s comparable benchmark. After all, the whole purpose of the portfolio is (usually) not merely to grow for the sake of growing, but to grow for the purpose of achieving a goal. Which means, arguably, the real focus should be on the investor’s progress towards their goals, not their (potentially short term) performance relative to some investment benchmark.

Yet in practice, benchmarking investment managers and financial advisors to goals may simply give them “credit” for favorable results that were really nothing more than the market delivering whatever the market was going to return – which is beyond the control of the manager anyway. And in a world where most financial projections are done with a straight-line return assumption, benchmarking to goals can actually quickly become the equivalent of a (relatively high) absolute return benchmark that is even more likely to lead to disappointing results that makes the manager look even worse (at least in the short term when the next inevitable bear market occurs).

More generally, though, the key is to recognize that even though investors should care about their investment results relative to a goal, the process of evaluating an advisor or manager and the value they do (or don’t) add to the process still needs a proper investment benchmark. In other words, there’s a difference between benchmarking the investor’s results to their goals (driven by the markets) and benchmarking the advisor’s or manager’s results (driven by their own investment decisions). And while benchmarking relative to goals may be appropriate to measure the former, it is still not an appropriate way to evaluate the latter!

Why Benchmarking Matters

In the context of business management, benchmarking studies help us to understand how the performance of our business measures up relative to peers, whether we’re spending more or less than others in overhead or technology, whether we’re generating a “typical” income for our efforts, and whether our pricing is competitive.

In the investment context, benchmarking is used to evaluate whether a portfolio/investment manager is performing better than what could have been achieved without paying the manager at all – in other words, whether the manager is beating the (passive) index alternative.

Of course, benchmarking results and whether you’re “doing well” – as a business, or an investment manager – depends heavily on what you use as the benchmark in the first place. As a result, having an “appropriate” benchmark is crucial.

In fact, this was arguably the greatest innovative contribution of the Morningstar Style Box when it was first developed. Because prior to the style box, equity managers were often all compared to the same standard “market” index, regardless of whether they tilted towards value or growth, large or small stocks. Which means sometimes, what was considered to be “great” performance (beating the market) was actually just the result of being a small-cap (or value, or some other) type of focused manager at a time that that whole segment of the market outperformed.

By controlling for the style of the manager in the first place, it become feasible to have a more appropriate and better-targeted benchmark… one that could effectively differentiate between a good small-cap manager, and a small-cap manager whose performance just looked good (relative to the broad market) simply because it was a time that all small-cap stocks were outperforming.

Of course, the underperforming manager might not want to be benchmarked at all, simply because it draws attention to their underperformance; yet in practice, benchmarking is crucial precisely because it creates accountability for poor performers.

Unfortunately, though, there is a dark side to benchmarking as well. Not only because sometimes investors judge too quickly based on short-term performance relative to a benchmark. But also because in order to beat a benchmark, it’s necessary to own investments that are materially different from the benchmark… yet doing so also risks underperforming it, in a world where one of the fastest ways to get fired is to take a wrong bet against the herd. In turn, this has led to the revelation that a non-trivial number of mutual funds have very little active share and are effectively just “closet indexing”. And more generally, many investment managers especially a fear/feeling that they must “stay in their box”, given the performance (and career) risk of deviating substantially from their benchmark. Even though hugging the benchmark – while charging ongoing fees – just leads to a virtual certainty that the manager will underperform that benchmark (by the amount of their fees)... as for a bad manager, it's likely still better to be fired slowly (and earn management fees in the meantime) than to "risk" being fired faster with active portfolio bets that may just hasten his/her demise!

From the financial advisor perspective, there has also been a growing frustration over the pressures that benchmarking exerts as well. In part because it seems to be getting genuinely more difficult to find alpha in the first place. And especially for those advisors that don’t even try to beat the markets and simply implement passive portfolios (and therefore feel they shouldn’t be benchmarked and judged against them). As well as those who simply don’t want the risk of potentially being fired by clients for what proves to be short-term underperformance. Especially given that, in the end, it’s arguably not really about whether the client beats the markets, per se, but whether he/she generates the returns necessary to achieve their financial planning goals in the first place.

Yet unfortunately, in the real world, this idea of simply “benchmarking to goals” may be an even more impossible benchmark to reach and beat!

The Problem With Benchmarking To Goals

To understand the potential problem with benchmarking investors to their (financial planning) goals, imagine for a moment an investor who was just getting started with an advisor over 15 years ago.

It would have been 2002, just after the bottom of the tech crash… where the investor had fired their previous advisor, and hired a new one, with the goal of retiring in 20 years. Assume that at the time, the investor had about $250,000 saved (by the end of 2002), with a goal to retire with $1.5M in 2022.

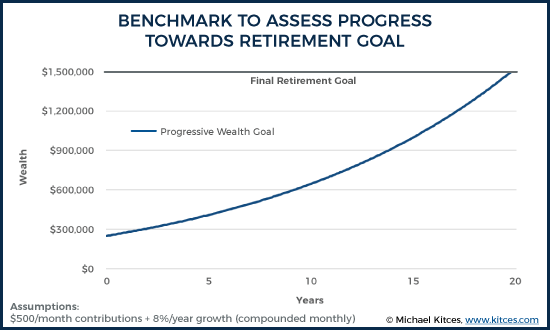

A financial planning projection at the time would have revealed that retiring over a 20-year time horizon was feasible by saving $500/month and earning an 8%/year average annual growth rate on a balanced growth portfolio (a typical return projection at the time).

Accordingly, the advisor created the following projection for the client to track (i.e., benchmark) progress towards the goal.

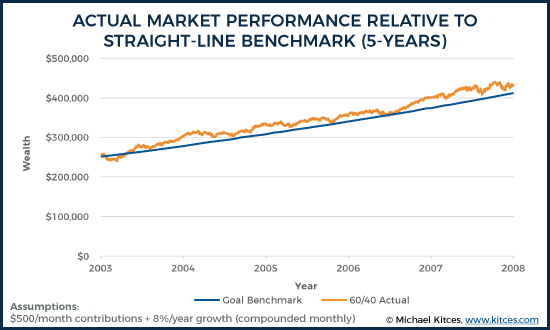

The advisor then invested the client into a 60/40 diversified portfolio of large-cap US stocks and intermediate-term government bonds, in order to achieve the desired rate of return.

As it turned out, though, over the subsequent 5 years, the post-tech-crash bull market generated more-than-enough of a return to keep the client ahead of their goal benchmark.

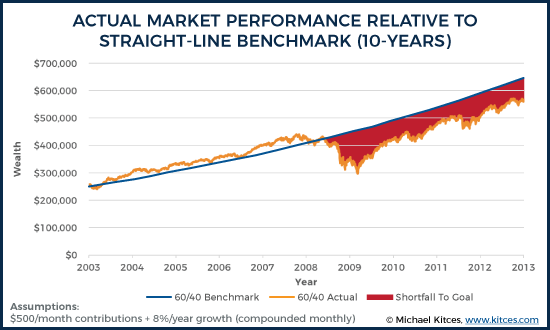

However, in the next 5 years, the severe market downturn of the financial crisis caused the client to fall well below the original goal benchmark, producing a substantial shortfall relative to the benchmark return!

Fortunately, in the past 5 years, the continued market rally after the financial crisis has brought the portfolio forward to the point that the investor is now getting close to the original goal benchmark again.

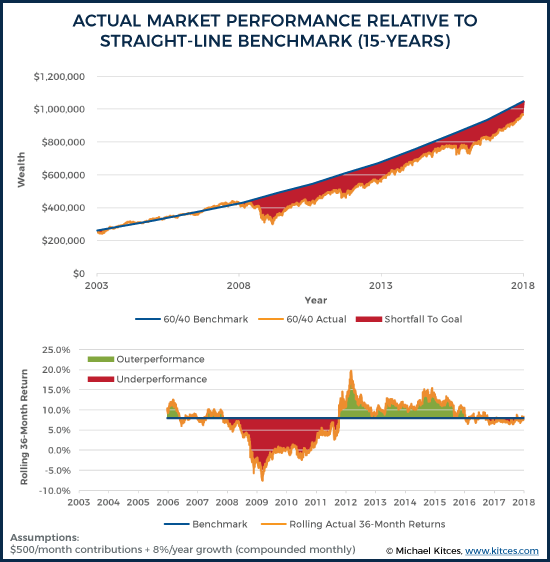

Nonetheless, though, the highly volatile markets over the past 15 years means the financial advisor has gone through substantial stretches of underperforming or outperforming the (goal-based) benchmark!

The key distinction, though, is that ultimately it wasn’t really the advisor and his/her investment recommendations that went through long stretches of underperformance and outperformance relative to the benchmark. The results were simply due to the cycles of the market itself! As the “relative strength” of the advisor’s portfolio compared to the client’s (goal) benchmark was really nothing more than a comparison of market returns to an 8% absolute straight-line-return benchmark.

In fact, the entire process of benchmarking to goals actually amounts to little more than evaluating annual (or rolling 3-year or whatever) performance of the markets relative to a long-term absolute return goal (the assumed growth/discount rate of the retirement or other goal projection).

Which, ironically, will often prove to be an even more challenging benchmark for advisors to beat over time! After all, it’s tough enough to manage clients who want good returns in bull markets and not to lose money (i.e., to earn cash returns) in bear markets. But it’s even harder to maintain a steady-state absolute return benchmark of +8% (or some similar number based on long-term return projections)!

Especially since the reality is that the advisor has nothing to do with the “good” performance during up years, nor the “bad” performance during bear markets, both of which are really just the result of the markets themselves. For which the advisor shouldn’t really receive any credit (good or bad) for the results. Market returns are what they are (and are beyond the control of the advisor anyway)!

Progress Towards Goals Vs Benchmarking Investment Results

Beyond the challenge that benchmarking to goals can end out being the equivalent of benchmarking to a relatively high-threshold absolute return portfolio, the second challenge is that it fails to achieve the actual purpose of benchmarking in the first place: to determine whether the investment advisor or portfolio manager themselves is actually adding value to the equation.

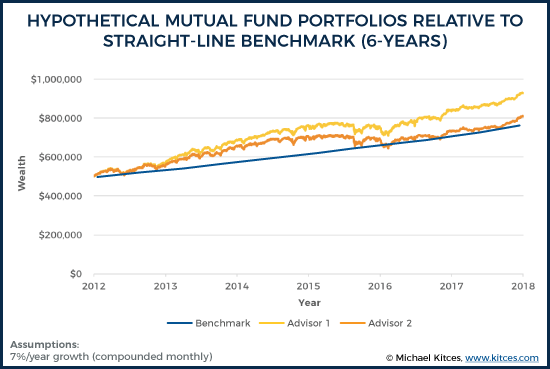

For instance, imagine two advisors who were hired 6+ years ago (at the beginning of 2012) to manage a client’s retirement funds. The client hopes to retire in 10 years, and needs a 7%/year return to achieve the goal with a moderate growth portfolio in today’s potentially-low-return environment.

The first advisor (Advisor 1) puts the client into a Fundamental Indexing equity fund (PRF), paired with the Double-Line Total Return Bond Fund for a fixed income allocation (DBLTX). The second advisor (Advisor 2) bought a series of higher-cost and actively managed funds that haven't performed as well since 2012, including Eaton Vance Tax-Managed Value Fund (EATVX) for the equity allocation and STAAR General Bond Fund (SITGX) for the bond allocation.

When benchmarked solely to the client’s goals, the good news is that both advisors were able to “outperform” the necessary return benchmark to keep the client on track to their goals (albeit one advisor by a bit more than the other, but both with very favorable results nonetheless).

However, the reality is that these “good” results had little to do with the advisors themselves. Instead, the results were driven almost entirely by the raging equity bull market that has been underway in recent years, due primarily to the monetary stimulus and economic recovery that followed the financial crisis.

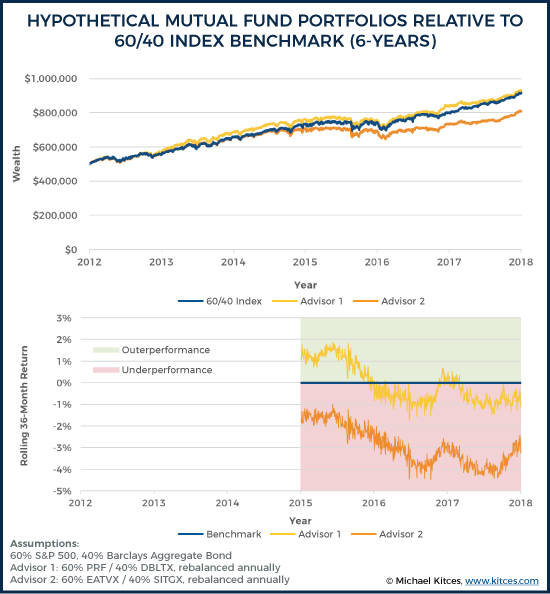

On the other hand, when the advisors are benchmarked relative to what a simple 60/40 portfolio of an S&P 500 index fund and a Barclays Aggregate Bond index fund could have achieved over the same time horizon, a very different result emerges… because in reality, one of these advisors generated substantially inferior results, in a manner that was completely masked by benchmarking to goals and is not evident until a proper investment benchmarking process occurs!

As these benchmarking results show, while both clients may be well on track to achieve their goals (thanks to the overall lift of the markets), only one of the advisors has actually added any (investment) value to the equation as well! The other is actually slowing the client’s progress towards their goals throughout, as good market returns are masking what is otherwise grossly inferior performance, due to having picked a series of especially poorly performing fund managers… which is only evident once the results of the advisor’s investment recommendations are actually benchmarked properly, and not benchmarked relative to goals!

Investor Results Vs Advisor Results

Ultimately, none of this is meant to suggest that it’s “bad” for investors to have better context of where they stand relative to their goals, whether they are on track, or to assign a clearer goals-based investing “purpose” to the funds beyond just seeking maximal return (with the caveat that investors don't always actually know what their real goals are in the first place!). But evaluating the results of the investor (which are primarily driven by what the market delivers relative to goals) are different than evaluating the results of the advisor or investment manager (which is all about the results relative to what the markets were delivering anyway, and whether the advisor or manger’s investment process is adding value).

Of course, for a growing number of financial advisors, their value proposition is not intended to be investment (out)performance anyway, but simply to “achieve” market returns (e.g., with index funds), and then add value in the financial planning process instead. For which a benchmarked portfolio will (correctly) show that the advisor’s results simply lag the market by the amount of their fees, and that they are not adding value in the investment selection process itself (as they weren't trying to in the first place!). Which in turn simply means such advisors will (or won’t) need to demonstrate their value in the client’s view by the non-performance financial planning value the advisor provides.

In other words, benchmarking an advisor’s investment results isn’t necessarily the only way to evaluate the advisor's value; nonetheless, to the extent that investment recommendations are even part of what the advisor delivers, benchmarking can and should remain highly relevant when it comes to actually evaluating the associated investment results. Especially for those who really are doing “something” in the portfolio that is intended to (hopefully favorably) impact the investment outcomes.

In the end, achieving client goals will be some combination of investor results (driven by markets), and advisor results (for whatever value-add they may bring with their investment process). But recognizing that each has a role also means recognizing that each needs to be benchmarked independently. Where investors may assess their own results relative to the goals they aim to achieve. But clients should still be able to benchmark advisors – at least those who aim to add value in the investment process – to an appropriate investment benchmark, to determine whether the advisor claiming to add investment value is really actually doing so!

So what do you think? Should advisors who manage portfolios still be benchmarked for their investment results? Are there situations where it’s appropriate to benchmark to goals (even if the results are driven by market forces beyond the advisor’s control)? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!