Executive Summary

(Note: For an updated discussion of the final 2017 GOP Tax Plan, see Individual Tax Planning Under The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act Of 2017.)

A key aspect of proposed tax reforms, ever since President Trump was on the campaign trail, was the possibility of reducing the tax rate on pass-through business entities like S corporations, LLCs, and partnerships. To some, the tax break was intended as an incentive for small business growth. For others, it was viewed as a necessity when proposed corporate tax reform and lower tax rates for C corporations would effectively put pass-through entities at a disadvantage without a similar break. Either way, there has been substantial momentum on the proposal, which was codified in both the House and Senate versions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

However, a key caveat of creating favorable treatment for pass-through businesses is to not unwittingly convert personal labor income – i.e., wages or self-employment income – into pass-through income eligible for favorable rates. Which at the least can distort the relative incentives of being an employee (paid as wages) versus self-employed (paid through a pass-through business entity). And at worst could incentivize employees to literally quit their jobs and try to get rehired as independent consultants – and paid through shell pass-through businesses – just to obtain favorable rates.

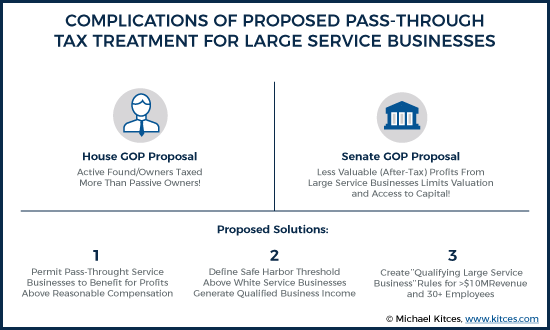

As a result, both the House and Senate proposals under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would limit the availability of the pass-through for so-called “service businesses”, either by eliminating the favorable rates for those who are “active participants” in a pass-through service business (in the House version), or simply eliminating the preferential treatment altogether for pass-through service businesses (in the Senate version).

Yet in practice, the actual mechanisms that both the House and Senate have created impose substantial economic burdens on large service businesses. Founder/employees of large service businesses (e.g., with $10M+ of employment income) can actually face marginal tax rates of 100%, 200%, or more on their wages as a leader of the firm, because their employment in their firm converts all their non-wage business income into less-favored ordinary income (under the House proposal). Large service businesses that want to scale may struggle to attract capital if their profits are literally “less valuable” on an after-tax basis to outside investors when all service business income is taxed less favorably (under the Senate proposal). And service businesses that also have non-service business lines will find their non-service income (otherwise eligible for favorable rates) becoming "tainted" by being wrapped under a service business.

Which means ultimately, if the goal is to reasonably separate “labor income” from “capital income” without distorting large service businesses, it’s necessary to adapt the rules further. One option is to simply codify a requirement that in service businesses, “reasonable compensation” must be paid (and taxed as wages), with only the excess eligible for favorable pass-through treatment (perhaps with a safe harbor to stipulate that any excess above a certain level of income is automatically eligible for pass-through treatment). Or alternatively, Congress could actually designate a “qualifying large service business” (e.g., with at least $10M of revenue and 30+ employees) that is automatically deemed to qualify its business income as favorable pass-through income (as such businesses typically already have governance mechanisms in place to ensure owner-employees are paid properly as owners for their labor, and separately for their pass-through business profits).

Without some solution, though, service businesses face substantial disadvantages in attracting capital, and/or outright disincentives for founders to continue to work – potentially with marginal tax rates in excess of 100%! Or alternatively, the current proposals may simply drive large service businesses to all recharacterize themselves as C corporations, in a world where the corporate tax rate would be dramatically lower (and even if the firm was deemed a Personal Service Corporation, would be taxed more favorably than a pass-through service business if top corporate tax rates are only 20%). Which would then disadvantage any service businesses that couldn’t effectively reorganize as a C corporation.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that while it’s an important matter of tax policy to tax labor income as labor income, and business income as business income… the reality is that in large service businesses, the profits of the business are substantially attributable to investments in capital (albeit human capital), and not just the fruits of an owner-employee’s personal labor. Good tax policy must recognize that difference.

Pass-Through Business Treatment Under The House GOP Plan

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as proposed by the House GOP, income from a pass-through entity – e.g., a partnership, LLC, or S corporation – would be eligible for a preferential maximum tax rate of just 25% (i.e., for those in a higher-than-25% tax bracket, their pass-through income would only be taxed at 25%). By contrast, under current law, income from pass-through entities is taxed as ordinary income, subject to regular Federal tax brackets as high as 39.6%.

To avoid abuse, though, the House GOP proposal stipulates that only pass-through income from a passive business activity (determined under the existing IRC Section 469 rules that determine passive vs active based on whether the owner “materially participates” in the business for at least 500 hours per year). In the business owner is an active participant, only 30% of their pass-through income is eligible for the preferential rate, while the other 70% is taxed as “labor” income (at ordinary income rates). An additional exception applies for “capital-intensive” businesses (e.g., manufacturing), where the capital percentage (the percentage of income eligible for the 25% rate) is not an arbitrary 30% of income, but a more complex calculation where the business owners’ total capital investments into the business are multiplied by an assumed rate of return (the Federal short-term rates plus 7%) and any remainder is treated as labor income.

As an additional limitation in the case of service businesses (as defined under IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A), which includes those performing services in various professional fields including health, law, engineering, architecture, accounting, athletics, consulting, financial services, etc.), the rules stipulate that no income can be treated as 25% business income and instead will all be taxed as ordinary income (unless the business owner can demonstrate a greater-than-0% capital percentage based on their actual capital contributions into the business). These limitations are meant to prevent individuals whose business income really is attributable to personal labor – i.e., rendering professional services – from recharacterizing what would otherwise be “wage” (or self-employment) income as “business” income. In practice, this provision also helps to prevent high-income employees from trying to obtain the favorable pass-through rates on their wages by pretending to be independent consultants and requesting their (former) employer to pay all their (former) wages to a pass-through consulting business.

Marginal Tax Rates For Employee-Owners Of Large Service Businesses Can Exceed 100%

Notably, the idea of trying to distinguish “labor income” from bona fide business profits is not new. Determining “reasonable compensation” for employee-owners of S corporations has long been a battleground issue for the IRS, as high-income S corporation owners have an incentive to minimize their wages and instead take their profits in the form of S corporation dividend distributions (which are still subject to ordinary income rates under current law, but avoid FICA taxes). In other words, S corporation owners try to minimize the allocation to “labor income” and maximize the allocation to “business income/profits”.

However, the House GOP proposal is substantively different than the issue of S corporation wages, as while with S corporations there’s a requirement to at least pay “reasonable compensation” (i.e., a market rate salary) and be taxed accordingly on that labor income. In the case of the House GOP plan, though, there’s no cap to the amount of income that is effectively treated as labor income, converting all of the business’ profits to ordinary income (instead of the 25% pass-through rate) as soon as the employee-owner reaches the “active participation” threshold (i.e., materially participates in the business for at least 500 hours per year, or certain other tests).

The reason this matters, is that it means large service businesses, where the bulk of the income really is from the efforts of other employees beyond the owner themselves, the owner can effectively be “punished” with marginal tax rates well in excess of 100% by choosing to be an active participant in their own business, instead of just a passive owner.

Example 1a. According to the latest Investment News benchmarking study for financial advisors, the average “Super Ensemble” firm (a firm with more than $10M in revenue, typically established about 30 years ago, with an average of 49 employees) generates $19.3M of total revenue and has 25% profit margin, generating a profit of $4.8M for 4 owners. These owners, according to the industry Compensation & Staffing studies, would typically include a CEO (median salary/bonus compensation of $300,000), a Chief Investment Officer (median compensation of $215,000), and perhaps several practicing partners (median compensation of $247,000). Which means in practice, these owner-employee incomes would be approximately 20% labor income (their fair market compensation for work in the business), and 80% from business profits (their pro-rata share of the $4.8M of profits). However, under the House GOP proposal, the entire $1.2M of profits plus almost $300k of labor compensation would be taxed at ordinary income rates, because they are all active participants in the business.

However, if the CEO of the firm chose to retire – walking away from their salary, but keeping their shares and profits interest – then the $1.2M of business profits would be eligible for the preferential 25% rate. Given that most of this income would be taxed at 39.6% rates under current law, this amounts to a savings of 14.6% on almost the entire $1.2M of profits on their shares, for a tax savings of $175,200. Of course, the CEO’s $300,000 salary was also subject to top tax rates of 39.6%, generating another $118,800 of taxes. Which means by not working, the CEO with a $300,000 salary saves $294,000 in taxes. Or viewed another way, the pass-through rules effectively created a 98% marginal tax rate on the actively employed owner of the business!

In situations where ownership is more concentrated, the problem is even worse.

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example, if the CEO was the founder of the firm and still owned 50% of the shares (and therefore participated in 50% of the profits, equal to $2.4M of business income for the business he/she spent 30 years building), then working in the business would tax the $2.4M of profits as ordinary income, but immediately retiring would tax those profits at the preferential 25% rate. Which means the business owner would instantly save over $350,000 in taxes by not working. Or viewed another way, working and taking a $300,000/year CEO salary in the business would have a marginal tax rate 156% (because the business owner would actually pay $469,200 of additional taxes on the $300,000 salary!). And the larger the business, and the more concentrated the ownership (i.e., the higher the portion of the business owner’s total income as profits), the more punitive the outcome. If the founder/CEO was actually still the sole owner of the business (which means he/she would receive all of the profits as either ordinary income as an active owner, or 25% pass-through income as a passive owner), the marginal tax rate on his/her $300,000 CEO salary would be 273%!

Similarly, even for “Junior” partners, the fact that business income is “converted” into ordinary income for active employees in the service business means any partner/owner who continues to work in the business faces unusually high marginal tax rates on their income relative to quitting the firm and “just” keeping their ownership shares and profits interest.

Example 2. In the earlier example, if the practicing partner was “just” a 5% owner, and earning $247,000/year of income as a practicing partner (which puts him/her into the 33% tax bracket as a married couple), their 5% profits interest (which is $240,000 on a $4.8M profits base) is taxed at 33% and 35% brackets (ordinary income rates) instead of 25%. Which increases his/her tax liability by an extra $20,000, effectively putting the partner’s wage income at a true marginal tax rate of over 40%. Or conversely, the partner could make save $20,000/year in taxes by working at any firm in the industry except the one he/she is a partner in! (Because then the profits would be “passive” income with respect to that business.)

More broadly, as these examples indirectly illustrate, if the business was simply sold by the founders/partners to third-party investors, its profits would magically be 58% more valuable… because the third-party investor (a passive owner employing all the advisors) would only be taxed at 25%, while the employee-owner would face tax rates up to 14.6 percentage points higher. Even if all the actual service work is being done by the same (non-owner) people!

The fundamental problem: it’s one thing to try ensure that bona fide wage income is taxed as ordinary income. But it’s quite another to convert all income of the business… which in a very large service business is actually a return on risk capital (to employ all the individuals actually providing services), not actually a return on the labor of the owner-employee (who is but one of many employees at that point!). In the most successful businesses, this can literally cause owner-employees to lose money by choosing to be gainfully employed in their own businesses!

Pass-Through Treatment Under The Senate GOP Plan

When it comes to the Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, preferential treatment is again available for pass-through businesses.

The Senate legislation, though, would not simply apply a preferential 25% rate (as with the House GOP proposal). Instead, pass-through businesses would be eligible for a deduction equal to 23% of the business’ income. Thus, for instance, if the business earned $1,000,000 of profits, it would be eligible for a 23% x $1,000,000 = $230,000 deduction, and only be taxed on $770,000 (which is 77% of the original income).

Or viewed another way, an individual in the top tax bracket (38.5% under the Senate proposal) would face a top tax rate on pass-through business income of only 29.6% (which is 77% of the full tax rate). Similarly, those in the 35% or 32% brackets (as proposed) would only be taxed at 26.9% and 24.6%, respectively, all the way down to a lowest tax rate of just 7.7% (which is 77% of the bottom 10% tax bracket). Since the Senate pass-through preference is a deduction against income, the actual value for any particular taxpayer would depend on which tax bracket the pass-through income had actually fallen in to.

Notably, though, there are several additional limitations in the Senate pass-through rules. The first is that the pass-through deduction for so-called “Qualified Business Income” would be limited to the lesser of 23% of the individual’s income, or 50% of his/her wages. Which means if the total income of the business was $1,000,000 but the owner also received a $300,000 salary, the deduction would only be $150,000 (which is 50% of wages), rather than $230,000 (which is 23% of business income). Similar to the House GOP proposal, this can effectively punish the tax rates on business profits for those who take a moderate salary but generate substantial pass-through income (whereas if the individual quits and becomes a passive owner, the 50%-of-wages limitation is moot, and the entire deduction of 23%-of-business-income becomes available again!).

To limit the risk of individuals with more moderate incomes losing most of the pass-through deduction due to low wages, an exception permits those with less than $500,000 of income (as a married couple, or $250,000 for individuals) to claim the 23% business income deduction regardless of the W-2 wage limit. However, this favorable treatment phases out quickly once these income thresholds are exceeded (as the W-2 wage limit is phased back in as income rises to $600,000 for married couples, or $300,000 for individuals).

In the case of personal service businesses, though, an additional limitation applies. Similar to the House GOP proposal, the Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would completely eliminate the preferential treatment for “specified service” businesses, which again includes all the professional service businesses described in IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) (for law, medicine, accounting, financial services, etc.). Which means any service firm – including lawyers, doctors, accountants, and financial advisors – would not be eligible for the favorable treatment, and would continue (as under current law) to report all pass-through income as ordinary income.

An “exception-to-the-exception”, though, retains the 23% deduction (or 50% of wages, if lower) for any service businesses where the individual owner/partner has taxable income of less than $500,000 (for married couples, or $250,000 for individuals). In other words, a partner who earns “just” $400,000 actually does get the 23%-of-income (or 50% of wages, if less) deduction. But once the partner’s taxable income exceeds the threshold, the deduction phases out, and is fully eliminated by $600,000 of taxable income (for married couples, or $300,000 for individuals).

Reduced Valuations And Access To Capital For Large Service Businesses

As discussed in a recent article by the Tax Policy Center, the phase-out of the deduction on pass-through qualified business income for service businesses as income rises from $500,000 to $600,000 (for married couples, or $250,000 to $300,000 for individuals) causes marginal Federal tax rates to spike over 70% (until the deduction is fully phased out).

However, arguably a more substantive problem exists for large service businesses: to the extent that they ever do need access to capital, the fact that the service business is taxed as such – and not eligible for the favorable treatment – the business becomes substantially less valuable for external investors, who will reduce a lower after-tax return on their capital for choosing to become passive owners in a service (rather than any other) business.

Example 3. A large $5B RIA, with revenues of $50M/year, a 26% profit margin (producing $13M of profits), employs 160 people (as a revenue/employee of >$300,000 is common in high-income professional service businesses). The firm decides that it would like to attract outside investors in order to acquire and consolidate local competitors for better economies of scale.

If the firm can attract investors who are willing to pay 8X free cash flow, the business would be valued at approximately $13M x 8x = $104M. An investor who bought a 20% stake would pay $20.8M, and have rights to $2.6M/year in profits as a return on their capital.

However, if that investor also had an opportunity to buy a similar manufacturing business, that wanted to raise similar capital to invest in a new factory and machinery, to generate similar profits, the opportunity to invest into the advisory firm is suddenly far less appealing. As even for the same $20.8M purchase price for $2.6M/year in profits, the investor will have to pay maximum rates of 39.6% for the service business, but only 30.5% on the manufacturing business (with the 23% deduction for qualified business income). Which means the investor would need to pay “only” $18M for their share – instead of $20.8M – to generate the same after-tax profits. Or viewed another way, the value of the service firm is effectively reduced by more than 13%, to make up for the higher tax burden on the profits of the service business.

As noted earlier, the fundamental purpose of the rules for service businesses is to ensure that active labor income from such businesses is taxed as labor income, and not income from capital that is eligible for preferential rates. Yet the reality is that, once service businesses grow very large and gain economies of scale, they must access and invest capital as any business does… for which less favorable tax treatment for capital investments into service businesses over other businesses can materially distort the valuation (and therefore, access to capital) of service businesses as they grow and scale. Even as the reality is that the income of the business is less and less connected to the labor of any individual owner/investor (as in the example above, where there are 160 employees, of which the owner is just one). Alternatively, such large service businesses may feel compelled to convert themselves into C corporations instead, which a prospective top tax rate of just 20% (instead of 39.6% as an ordinary income pass-through), just to retain more profits to reinvest for hiring purposes.

Even worse, businesses that have both service and non-service related functions (e.g., a medical practice that also sells medical equipment) might need to separate out their service business lines from non-services into distinct entities, just to ensure that the non-service income isn't "tainted" by being wrapped up in a service business - since, again, the Senate proposal would reduce the favorable tax treatment for all business profits (from service and non-service business lines) as long as they're housed together.

Tax Policy Solutions To Resolve The Distortions On Pass-Through Income For Large Service Businesses

Ultimately, the fundamental issue in both the House and Senate proposals is that they are treating individual service businesses the same as large service businesses. And while it’s reasonable policy to try to ensure that wage earners don’t use pass-through businesses to convert labor income into business eligible, the reality is that in individual service businesses, most/all of the profits really are driven by the labor efforts of the founder/owners/partners, but in large service businesses, the bulk of the profits come from investing into the [human] capital of employees, and not the personal labor of the owners. Or viewed another way, once a service business reaches scale, there’s little substantive difference in the profits from “capital-intensive” manufacturing, versus “capital-intensive” labor costs of scaling a service business up to dozens or hundreds of employees.

Thus, from a policy perspective, the pass-through rules for service businesses need to consider the distinction between large service businesses, and truly “personal” service businesses that are solely or primarily driven by the labor of the owner. Otherwise, as noted above, successful business owners face marginal tax rates in excess of 100%, and challenges attracting investors to hire service providers that produce lower after-tax profits, because of the failure to separate the profits of a large service business from the wages of the business owner. Or alternatively, large pass-through service businesses will be highly incentivized to restructure as C corporations to try to take advantage of much-lower corporate tax rates as well, which introduces others costs and complexities (and may not always be feasible given varying shareholder interests).

In practice, there are a few ways to potentially handle this from a policy perspective, to make it less "necessary" to convert pass-through businesses to C corporations because of (comparatively) punishing pass-through taxation terms.

The first is to establish a “reasonable compensation” requirement for service businesses, similar to how the rules are currently applied for S corporations. This would require all service businesses to pay a reasonable wage to owner-employees (a salary in an S corporation, or a guaranteed payment for a partnership or LLC), and any salary/guaranteed payments would be taxed as ordinary income (as they currently are). Any additional business income above reasonable compensation – to the extent there is any – would then be eligible for favorable treatment as a pass-through business. Notably, this would also eliminate the need/pressure for businesses to split into separate business lines to parse out the non-service-business income from the rest of the services business, just to avoid the unfavorable service classification on non-service income.

Given the challenges in determining “reasonable compensation” – at least in some service industries – a second alternative might be to create a clear safe harbor definition for what constitutes “reasonable compensation” in the first place. For instance, this might mean an assumption that any service income up to a specific dollar amount, like $500,000 or $1M, will be treated as labor income (subject to ordinary income). But any additional profits beyond the threshold would be eligible for pass-through rates. After all, earning $1M/year in actual service income is very difficult; with 2,000 working hours in a year, it would necessitate averaging $500/hour, and given that most service businesses are only able to bill out 60% to 70% of their time (given the need to handle administrative tasks, professional development, and other business functions), a $1M threshold would be the equivalent of billing $714 - $833/hour. It seems reasonable to assume that income above such thresholds is likely no longer attributable to “just” labor income, but also human capital investments in the other employees of the business.

A third option, which might be combined with the second, is to specifically define a “large service business” that is exempt from the general “service business” rules, and instead follows the “normal” rules for allowing favorable treatment for pass-through businesses (beyond any salary or guaranteed payments already being made).

For instance, a “qualifying large service business” might be defined as one that generates at least $10M of revenue, perhaps also with a requirement for a minimum number of employees (e.g., at least 30 employees). If a service firm is at that size, it must have multiple professionals, by definition has lots of employees (with an employee count requirement), and the bulk of the profits are not just the effort of the individual labor of the owner(s). In such a qualifying large service business, all pass-through income (but not salaries or guaranteed payments) would then be made eligible for favorable rates (and the W-2 wages limitation for the qualified business income deduction would be removed, as it would be a moot point). Additional carve-outs could be created for large service businesses not intended to be captured (e.g., for hedge funds that are primarily in the business of investing their own capital).

And in practice, such a large service business will very likely already be paying “market rates” of income to key owner-employees, because it’s necessary to effectively manage the profit-and-loss statement of the business (as underpaying certain key employees ends out tilting profits to other owners). In other words, diversified ownership and normal governance mechanisms of sizeable businesses tends to ensure that all employees – including owner-employees – are paid reasonable income, to ensure that the remaining profits are allocated properly to the owners. Which means by definition the remaining profits should all be profits due to capital, and not attributable to labor service income.

Of course, there are likely a lot of financial advisors (and service providers in other professions) who wish that the pass-through tax break would apply to all of their income. But when the underlying policy goal is to continue to tax labor income as wages (at ordinary income rates), and it’s important to avoid having employees convert income to being paid to a consultancy via a pass-through, having some prudent rules are necessary.

Nonetheless, the current proposals – from both the House and Senate – have unwittingly created prohibitive greater-than-100% tax rates on founders and key employees of large service businesses, and/or material real-world limits in their ability to access capital to hire and grow, because of the less favorable treatment of investing capital to hire people (instead of investing capital to build factories or “hire robots” instead)! Which either unduly punishes those businesses for focusing on services, or drives them to look at alternative corporate structures for loopholes (e.g., converting to a C corporation, as with a maximum corporate tax rate of 20%, even being taxed as a “Personal Service Corporation” may only be subject to a 20% rate!).

In other words, recognizing the difference between bona fide wage income, and bona fide profits of a service business, is essential. But that means owner/employees should simply be required to pay taxes on “reasonable compensation” wages, while allowing the additional profits of successful business creation to be taxed like other large successful business profits… regardless of whether the profits are generating by hiring people or building factories!

So what do you think? Should the House and Senate proposals under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act be reformed to better address the realities of large service businesses? How would you propose the rules be adjusted? Please share your thoughts in the Comments below!

Michael, now that the conference committee is done, I am interested in what actually emerged on this. It could be a sea change in how we plan for ourselves and our business clients.

This is NOT good news. One item what about the 1987 Ron Lykins Inc. case discussed in the September 1, 2006 Journal of Accountancy where it was ruled that financial services is not personal service corporation activity. Not seeing how the new laws would change this court case ruling.

Unfortunately, the code reference IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) Michael linked above specifically includes financial services.

With FIFO still on the table, can you comment on the idea of moving certain lots of a given stock one owns (to wit, the highest acquisition cost) to a different taxable account, so that one side steps the FIFO change?

Clearly this needs to be done prior to initiation of FIFO, so in the waning days of 2017.

My prediction is that they will pass an imperfect tax bill and come back to it at a later time. If Democrats take over either the house or the senate, the chances of a fix would go down. So some parts of the tax code get simplified and another parts get pretty complicated. On the bright side, this tax bill will make it very easy for future CFP exam question writers. There is going to be so many twists.

There really should be no difference in tax rates for any income: labor, pass-through, or capital gains. The preference of certain sources of income over others only encourages complexity, inefficiency, and wealth disparity. My view has evolved on this over the past 20 years, but I’m more and more convinced each year (I had all three sources of income on my 2016 return).

Waiting for some financial genus to create an exchange fund (similar to that for concentrated stock positions) but for owners of S-corp financial advisory firms. Deposit your shares into a fund and receive pass through income which you are not actively involved.

Excellent article – very helpful to understand the moving parts and landscape. I do have one point of contention: I think that the distinction that Michael makes between large and small practices is largely artificial. Many small practices have income dynamics, capital investments, and workflow realities that are comparable to large firms – the advisor accomplishes the bulk of the work through other people, the total compensation for the advisor is far above what would be expected on an hourly basis, and the advisor must make tradeoffs when evaluating reinvesting in technology, training, etc.. The scale is just smaller. If you are the sole owner of a practice with $1.5M in revenue, net $800K, and have a team of 3-4 running the operations, you are investing just as heavily on a percentage basis back into your people, technology, systems, etc. The only different piece is that you cannot as easily raise capital for expansion. It would be difficult to argue that it is just (or even primarily) the advisor’s work that is driving the value of the practice in my scenario above. If the owner dies and has a buy-sell agreement in place, there is significant enterprise value. A business like the one in my example above would not garner the same multiple on revenue or profits that Michael uses for large service business examples in the article, but there is still significant enterprise value of some of the smaller firms.

Spenser,

The messines is figuring out where to draw the line between “labor income” and income from the enterprise value of the business.

Across multiple industries (not just financial advisors), there really are professionals who get paid $800 – $1,000 per hour (certain doctors and lawyers in specialties), where they really could generate $1M+ in profits from personal labor. And a few of them partnered together could have a multi-million-dollar revenue business from personal labor.

The messy policy challenge is figuring out where/how to draw the lines to not give preferences to the highest-income professionals, while recognizing service businesses that are scaling.

I’m not specifically attached to the exact thresholds I defined in the article here for large service businesses. But from a practical perspective, getting a change through Congress on this will require being able to draw a substantive line that “ensures” we’re talking about scaling service businesses with a high volume of employees, and not just a group of high-income professionals themselves (whose income should be taxed as labor income).

– Michael

Thanks for your response, Michael. This really is a messy topic. After looking back at your proposals, I would hope that multiple paths are offered – perhaps a safe-harbor on personal income and a safe-harbor on firm size. I agree that “reasonable compensation” language tends to abused and there probably need to be more substantive guidelines. As always, excellent work on your research! Thanks much.

So (under the Senate bill), for the one person S Corp RIA in which the advisor takes a $200,000 salary and a $100,000 profit distribution, she would receive a $23,000 deduction and (assuming a non-working spouse) pay tax on $77,000 at the married-filing-jointly marginal rate? Do I have that right?

This is my same question. Hope you get an answer

Steve,

That’s correct, at least with respect to the passthrough. The Advisor’s total income would be $277,000 in the end, including the $200k of salary, the $100k of profits, and the $23k of deductions against the profits.

Of course, other household deductions may apply as well. And at last revision, the deduction had been reduced from 23% to 20%. There’s also still discussion of further edits and revisions to the final pass-through provisions. We’ll know soon enough…

– Michael

Thanks, Michael. We all owe you a beer. At the very least!

Thank you for the clarification. Great post as ever.

Looks like the conference report capped (started a phaseout?) the amount at $315,000 (MFJ) – the top of the new 22% bracket.

Yup, it was originally a phaseout starting at $500k MFJ ($250k individual) but was reduced in the final version.

– Michael

Effectively a 17.6% rate. Down from 28/33%.

The reporting I see now has the 24% (not the 22%) bracket top out at $315,000 for MFJ. With the 22% bracket ending at $165,000. So effective marginal rate (after the QBI deduction) for income between $165,000 and $315,000 = 19.2%.

So much for simplification…!

Seems to make a good case for federal taxation to be based on consumption not income.

I will have about 100k of pass thru income I believe will result in a 20,000 dollar deduction. Is that an above line deduction? Meaning can I reduce my income 20,000 dollars and still take the standard deduction? Or will I be forced to itemize? I would be better off if I didn’t have to itemize hence the question. THANK YOU

So I have a small specialty insurance business (LLC sole prop) and expect to have a gross income of $410,000 and a taxable income from the business of about $275,000 after deduction of business expenses. I also pay 2 agents some commission on a 1099. I also file a joint return with my wife. What I am confused about is how the income below $315,000(joint filers) and $157,500 other filers language allowing one to claim the deduction fully on income from service industries would apply in my case.

Check out the Taxmode app – it has the 2018 TCNJ computations already implemented. I use it on iPhone, it is also available for Android.