Executive Summary

Financial advisors have used various personality assessments with their clients for decades as a way to identify risk tolerance and to make the right asset allocation decisions. With the growing focus on financial psychology in recent years, though, many advisors have sought to better understand their clients’ behaviors and biases around money, with the ultimate goal of helping them make better financial decisions. In response, there has been a proliferation of behavioral assessments that purport to offer valuable insights into a subject’s psychological characteristics. However, without industry regulations for how these tests are developed, financial advisors need to recognize how to select the right assessments to use with their clients. Yet, how do we know whether an assessment actually gives an accurate psychological profile of our clients? Having at least a baseline understanding of psychometrics – the science of measuring unseen, personal characteristics – can provide a way to determine not only how useful an assessment can actually be for advisors to better understand the client, but also how to select suitable tools based on their psychometric properties.

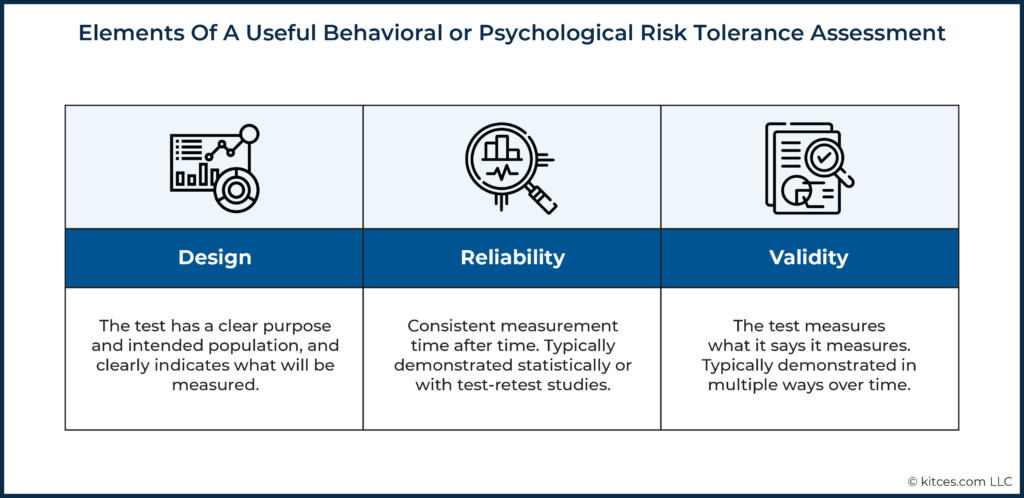

The usefulness of a test can be judged according to three key elements: design, reliability, and validity. A test with a good design will clearly identify its purpose and the population it was designed for, and will also be engineered to eliminate error and bias from the results. A reliable assessment will provide consistent results each time it is administered, and a valid assessment will measure specifically what it claims to measure. A good test will also have had statistical analyses conducted that confirm the reliability and validity of its design, with published results so its users (e.g., advisors and their firms) can review the developers’ efforts to construct accurate assessments.

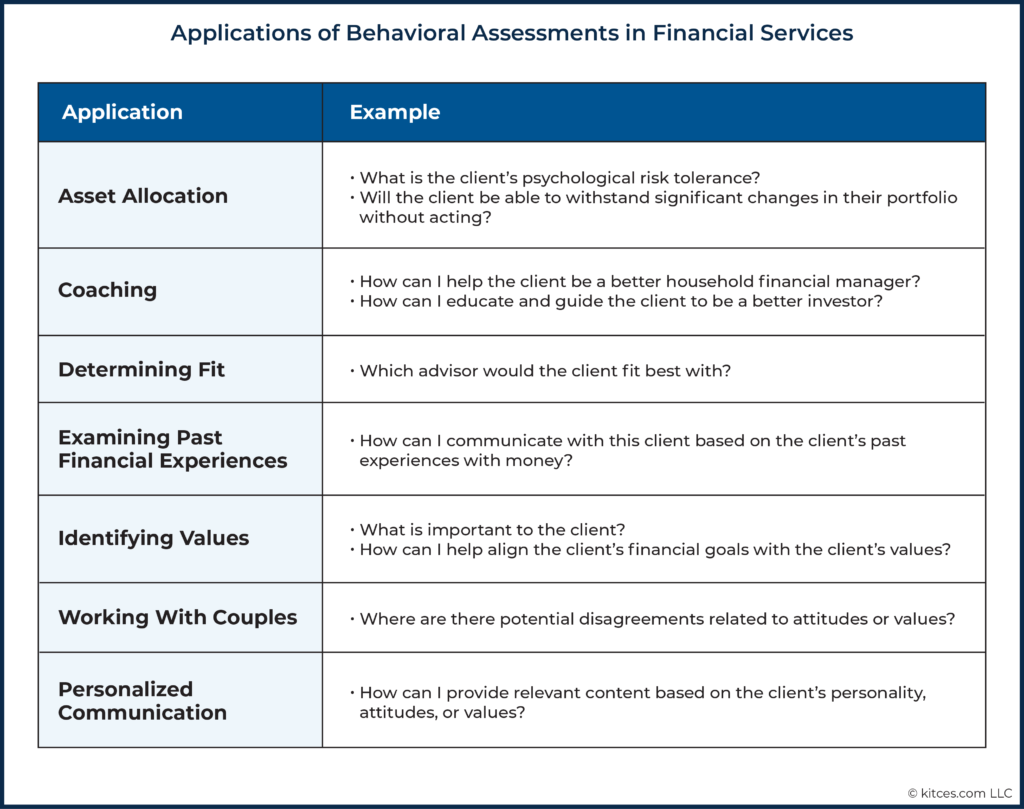

One of the core functions of psychometric assessments in the context of financial planning is to measure a client’s psychological risk tolerance in order to predict their behavior in various market conditions. Knowing which clients might be inclined to make poor decisions in up and/or down markets can help advisors focus attention where it is needed most during those often intense and stressful periods. Psychometric tests also aim to examine a client’s enduring traits, which remain relatively stable over time and can therefore be used to predict the client’s behavior in conditions different from those in which they took the assessment—an important attribute in an industry where market conditions and client behavior can both be highly unpredictable.

Beyond serving as traditional risk tolerance surveys, psychometric assessments can also help advisors to understand a client’s communication style, personality, and saving and spending behaviors more objectively and at a deeper level than their own subjective judgment (which can be fraught with biases and sometimes even knowledge gaps of the client’s personal circumstances). As the topic of financial psychology becomes more prominent in our field (as evidenced by the CFP Board’s inclusion of “Psychology of Financial Planning” in its list of Principal Knowledge Topics), it becomes increasingly important for advisors to better understand their clients’ behavioral and emotional traits to improve communication, behavior, and, ultimately, the financial planning recommendations given to their clients.

Ultimately, the key point is that when chosen carefully and used correctly, well-designed psychometric assessments can give advisors valuable information about their clients that cannot be obtained by a simple form, survey, or interview. With insight into their clients’ inherent psychological traits – which are often hidden beneath layers of personality – advisors can better position themselves to deliver financial plans that will more effectively ‘stick’ with their clients!

Psychometrics is the field within psychology that is devoted to the measurement of human abilities or characteristics, particularly those that are difficult to measure or are unseen. The American Psychological Association (APA) defines psychometrics as:

The branch of psychology concerned with the quantification and measurement of mental attributes, behavior, performance, and the like, as well as with the design, analysis, and improvement of the tests, questionnaires, and other instruments used in such measurement.

Psychometricians typically have a strong background in psychological measurement and statistics, and use that knowledge base in conjunction with professional guidelines, such as the Standards for Educational and Psychological Measurement from the APA, to create and publish assessments. Guidelines such as these provide clear ways in which psychological tests should be constructed, administered, and interpreted. While not a perfect science, there are legal requirements that tend to weed out assessments that are less-than-scientific (that should be used with caution, if at all) from the marketplace, particularly in the context of decision-making related to college entrance or personnel selection.

The use of behavioral assessments in financial services is still in its infancy, although there is documented utility of psychometric assessments in the fields of education, personnel selection, and leadership development. Tests have benefits for those in financial services, particularly in providing an efficient and unbiased assessment of stable client characteristics (i.e., client traits or attributes that are unlikely to change over time) that could be critical in designing a financial plan and/or investment strategy that the client will likely be able to adhere to.

Psychometrics Provides A Framework To Understand The Usefulness Of A Test

The usefulness of psychometric tests in financial services is only as good as its design. In other words, if a test is not well-designed to be reliable and valid, it could lead to inaccurate results, or worse, potentially inappropriate decisions related to investment allocations or client fit.

Accordingly, an assessment with a good design will clearly identify its purpose and intended population (i.e., what group the test was designed for), and will also indicate what it aims to measure. A reliable assessment will provide consistent methods of measurement each time the test is administered. A valid assessment will measure specifically what it says it aims to measure.

The Basis For The Usefulness And Accuracy Of A Test Is In Its Design

It is important for an advisor to assess whether a particular assessment is well designed, as a test can only be useful if it is able to examine what the advisor wants to measure in (or better understand about) their client. In fact, in the world of psychometrics, it is standard for tests to be well-documented in a technical manual, so that an advisor (or their firm) can evaluate it before choosing whether to implement it with clients. After all, at best, the goal is to make a test that can reliably identify something we cannot observe directly – which is no small feat!

There are a few theories that support using tests to measure client characteristics such as personality. Classical Test Theory (CTT), which is the most common framework for behavioral assessments used in financial services, espouses that the Observed Score (O) a client registers on any psychometric assessment is made up of the client’s True Score (T) plus an Error (E) factor.

O = T + E

Client’s Observed Score = Client’s True Score + Error

For example, let’s assume we want to measure a client’s level of extraversion, the personality characteristic that is associated with being energized (high) or being exhausted (low) by being in the company of others. What we see on a report about a client’s extraversion would be the client’s actual score (measured by their True Score, T) plus some amount of other ‘stuff’ (the Error, E) that has nothing to do with the client’s true level of their extraversion. In other words, the framework recognizes upfront that, when measuring an abstract psychological trait, we can never truly ‘know’ what its score would be; at best, our measurement is an estimate, plus or minus some Error.

Errors can arise from a number of sources, including how the test was created, how it has been implemented, and things beyond our control (i.e., random error and ‘noise’). To make sure that the client’s Observed Score is as close as possible to their True Score, test developers try to eliminate as much Error as possible when the test is designed, which is where the methodologies of psychometrics become important. This is to say that whether advisors are using an assessment created in-house or an off-the-shelf assessment created by a test developer, the usefulness and accuracy of any test is the result of its design, particularly how well the Error component is consistently minimized in the assessment.

So, what does ‘good test design’ look like? The following sections provide insight into the test design process as a way to give firms a basic overview of what to look for when selecting behavioral assessments. While there are many sophisticated analyses and time-consuming steps psychometricians take to create assessments, there are four basic steps that any test developer should take when creating a test.

In essence, creating a sound psychological assessment boils down to four basic steps:

- Identify the purpose of the test and the intended population;

- Define what the test measures and why (construct and/or model identification);

- Engineer the test to eliminate as much error and bias as possible (item and test design); and

- Conduct statistical analyses to confirm design (reliability & validity analyses).

Any reputable test publisher should provide documentation about the steps above (usually in the form of a technical manual for the test). Having a high-level understanding of these basics of test development processes, discussed in the following sections, can help advisors evaluate assessments for use in their firms.

Purpose of Test And Target Population

Test developers should have a clear definition of the purpose of the test in mind and understand how it will ultimately be used. This includes knowing who the target population will be, which drives later analyses and applicability.

For instance, creating a test designed to assess money values with a population of mass affluent clients and then later using the assessment of their money preferences as a measure of risk tolerance with ultra-high-net-worth clients may not make sense. Similarly, creating an assessment of whether a client can afford to experience portfolio losses and still have time to recover and reach their goals isn’t necessarily the same as measuring whether they have the tolerance to withstand that volatility.

Construct And Model Identification

Test designers should clearly define the constructs (another term for psychological characteristics of interest), and the model or research that gives some credibility to the rationale for creating the test in the first place. Construct and model identification ensures that there is sound theory and research behind what is being measured in the assessment. This step helps to ensure that the client characteristics we are interested in measuring have prior evidence of validity (discussed later) or, at the very least, some theory for why measuring the construct(s) on the test is important.

For example, the NEO-PI, one of the most highly regarded assessments of human personality, has as its basis the well-researched five-factor model of personality. The five-factor model includes five clearly defined and orthogonal (or unique) psychological constructs (i.e., client characteristics). We can infer that the test, at the very least, is based on sound research, and that each characteristic is unique. We can also make this inference with regards to the Strong Interest Inventory, an assessment that can help everyone from high school seniors to those nearing retirement understand their interests. This test has, at its core, a well-researched and documented model, Holland’s RIASEC model.

Item And Test Design

Once we are confident that we know what we’re measuring, we have to somehow ask clients to share information with us that will measure these characteristics. A psychometrician writes ‘items’ that clients will respond to, and designs the test to present the items in such a way that the client can respond without adding more error (for example, thinking about whether the client will get tired in answering so many questions, or how much a client would have to scroll to answer the questions).

Items refer to either statements or questions that capture the essence or measure each of the characteristics identified in the model. Item writing is both a science and an art, requiring the creation of the statement itself, along with the item responses (i.e., the ‘answers’ or response options to each question).

Some examples of item response formats include using multiple-choice formats (e.g., responses on a scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’) or forcing the client to choose between two options that are similar in desirability (e.g., “Which is most like you? (a) Honest or (b) Kind”).

Item writing teams might be involved, and having others review the items for bias, unclear language, or cultural references is a best practice. Items should be clear and not require a high level of reading ability or specialized knowledge (unless, of course, we’re designing a specialized knowledge assessment). For example, psychological risk tolerance assessments should not require the client to have advanced knowledge of investment strategies or even investment industry jargon, unless the purpose is specifically to measure investment knowledge.

Once items are written and appropriate item analyses are conducted, the test should be designed in such a way that the client reacts positively to the design and doesn’t feel fatigued after taking the test (or worse, during the middle of it). The instructions, the order of the items, how many items will be included on a screen, and the length of the test, in general, must be well thought out by the test developer.

Reliability Places A Ceiling On Validity: Tests Should Be Reliable

Imagine you've just received a new bathroom scale, and you weigh yourself each morning at 8:00 a.m. for seven days in a row. If you receive vastly different numbers each time you weigh yourself on a scale, you might question your diet and exercise routine. However, most of us realize that our weight should be relatively consistent (at least over short periods of time), and so if your weight fluctuated wildly from day to day, you might also consider why the scale is not providing a more consistent measurement.

In the world of psychological testing, we would say that your scale is not reliable. And because the scale is not reliable, it cannot be an accurate (or valid) measure of how much you weigh. There’s too much error that we cannot remove.

Thus, once the test is designed, it’s important to conduct statistical analyses to ensure that the test is reliable. Reliability is typically defined as how consistently a test measures a specific client characteristic, particularly client characteristics (traits) that should be stable over time. You can think of a test being reliable when clients who take a personality test on Day 1 have roughly the same scores on the test on Day 30.

On the other hand, when tests are unreliable, it is nearly impossible to understand the nature of the characteristic being measured. Or stated more directly – if the struggle is that every time the client takes the risk tolerance questionnaire they get a substantively different score, earning high marks when the markets are up and low marks when the market is down, that’s not a sign that “risk tolerance can’t be measured”; rather, it’s a sign of a not-well-designed (i.e., unreliable) risk tolerance questionnaire!

Validity Offers Ongoing Evidence That A Test Does What It Says It Does

Reliability provides some comfort that the test you are using is measuring something in a consistent way – consistent in the sense that the measurement doesn’t change depending on the weather or the markets. Reliability does not, however, help you know that the test is measuring what it says it is measuring (i.e., what it was intended to measure). To ensure the test is truly useful, we have to consider whether the test has evidence of validity. In its simplest terms, validation studies help to answer the question of, “Does this test do what it says it does?” Most psychometricians will rightly point out that a test is never truly ‘valid’ – only that it is approaching validity (because we can never truly measure an abstract trait; at best, we can estimate it well, and minimize the error of that estimate).

Validation is an ongoing process for the life of the test. Evidence of validity should be demonstrated in multiple ways, and over time.

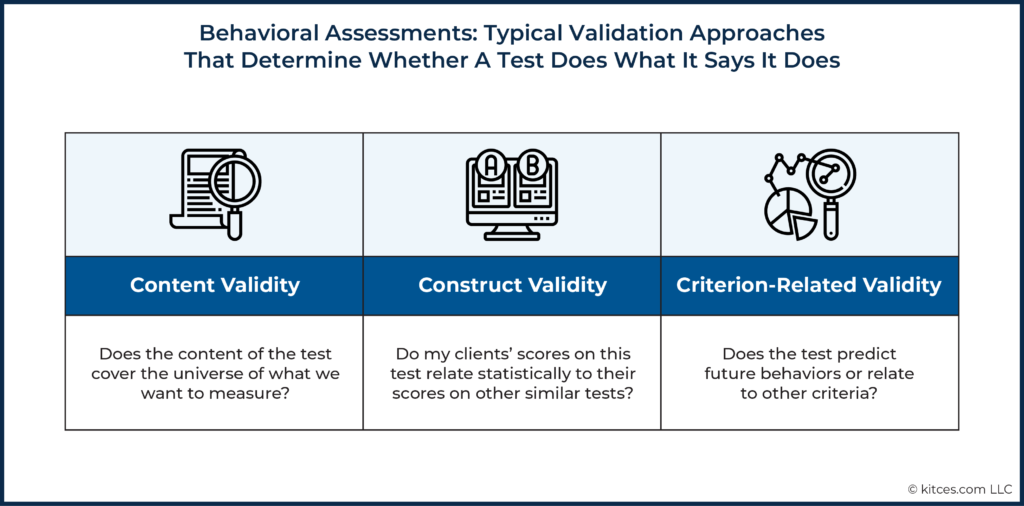

In practice, there are a few different ways a psychometrician can demonstrate that their test is ‘approaching’ validity: content validity (does the test cover what it should?), construct validity (do clients’ scores relate to their scores on other similar tests?), and criterion-related validity (does the test actually predict future behaviors?).

Content Validity: Do The Test Questions Adequately Capture The Characteristic I’m Trying To Measure?

Imagine you want to measure a prospective client’s optimism about the future. Through some amount of experience, you’ve decided that you work best with clients that tend to have a rosy outlook on life, and you consider that to be a critical component of the kinds of clients you want to work with. How many questions do we need to accurately capture the client characteristic of ‘optimism’?

If a test includes every possible question that could measure optimism, the client would be taking a 200+ question test. This type of test may be highly accurate, but is probably not the ideal client experience you or the client would want! If we ask only one question, on the other hand, there could be a chance that the question by itself does not address all the relevant things that might make a particular client optimistic and, therefore, may not be an accurate assessment of optimism by itself.

For example, asking a client whether they agree with this statement only measures the outlook that the client has today:

I have a positive outlook on life. [outlook today]

A client’s response to a statement such as the one above may fail to properly assess optimism for a client who is truly optimistic if this client just so happens to be in a bad mood that day. Instead, we might include a few additional questions that cover many different scenarios or experiences the client has had that could help us get closer to the ‘true’ optimism level:

Others have described me as optimistic. [judgments from others]

I have had a positive attitude throughout my life. [outlook in the past]

I usually expect the worst from life. [outlook today; responses to a statement like this would be “reverse scored”, where agreeing with this statement would equate to a lower score on optimism]

Additionally, we would want to make sure we remove questions that do not measure optimism, even if they seem similar. Here are a few:

Others would describe me as a good friend.

[Good friends might be optimistic, but this may not always be the case; being a good friend does not necessarily mean that they are optimistic (although optimistic clients might be a good friend).]

I enjoy trying new things.

[Trying new things might be a sign of optimism, but it also could simply be a sign of being open to change or being creative.]

Don Zhang, Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Louisiana State University, provided a succinct example of content validity related to measuring the characteristic of athleticism:

The 40-yard dash would be a better test [of athleticism] than a hot dog eating contest because, in theory, speed is one aspect of athletic ability, and hot-dog eating is not. You also need to make sure all aspects of athleticism are measured: If you only use the bench press but do not ask the players to run, you are missing out on important aspects of a person’s athletic ability. Psychological measures work the same way. If a survey is designed to measure conscientiousness, it needs to have all the items related to the concept of conscientiousness.

Content validation involves relying on a clear definition of each characteristic (or again, ‘construct’) and writing and reviewing items to adequately measure that characteristic. Advisors can check if the test being considered has some evidence of content validity by reviewing the development procedures in the test’s technical manual, and seeing if the test publisher included subject matter experts (SMEs) in the item writing or reviewing process. Other important factors to check include determining whether there is evidence that a large pool of items was created and then reviewed by the SMEs, and whether the pool of items refined over time was based on the SMEs’ judgment or a rating process. Evidence of content validity (and the rigor of establishing it) is most often a critical component of knowledge-based or education-type assessments.

Nerd Note:

Another type of validity that is often referred to in the behavioral assessment world is “face validity”, which is more of a judgment call as to the relevancy of the test. Does the test look like a test that should be used in financial planning or financial services in general? Do the questions, on the face of the test, appear to be relevant to money management, the client’s stage of life, and what is being measured? Note, however, that a test can look relevant (that is, be “face valid”) and still lack evidence of validity.

Construct Validity: Is This Test Measuring The Characteristic It Says It’s Measuring?

One way to ensure the test we’ve created is measuring a specific client characteristic (in our example, optimism) is to show that clients’ scores on our new optimism test relate to other measures of optimism. Statistically relating two measures that are supposed to measure similar constructs is a step in the direction of demonstrating what’s known as construct validity. To ensure construct validity, psychometricians take the time to relate a new test to other, previously published or available measures (tests, interview questions, ratings) of the same construct.

As an example, the DataPoints assessment of psychological risk tolerance was created to measure multiple characteristics (e.g., confidence, composure) as well as to provide an overall psychological risk tolerance score. To ensure each component of the test was approaching validity, the research team determined the statistical relationship between each characteristic measured by the test with similarly designed and previously published assessments that were theoretically aligned.

By examining the construct validity of each scale, we could be assured that our assessment was getting closer and closer to measuring what it says it measures (that is, approaching validity). These types of studies can be time-consuming from the test developer’s perspective but can provide assurance that the client characteristics measured on the test are sound.

Criterion-Related Validity: Does This Test Relate To Some Outcome Critical To My Business?

Even if the test questions are broad enough to measure the characteristic we’re interested in (content validity) and there is evidence that our test relates to other similar tests (construct validity), it is still in our best interest to know if the test can relate or predict some business outcome that is critical to the client (or to you).

For example, if you are using a risk tolerance assessment as a component of your allocation decision for a client, the validation evidence for that test should be that a psychological risk tolerance score relates to a client’s behavior or mindset during times of market turmoil, as in the case of the Grable & Lytton test (see below). Again, notwithstanding the experience of many advisors that their clients may score well (i.e., highly tolerant) on a risk tolerance questionnaire and then panic when markets get volatile is not evidence that risk tolerance cannot be measured; it is an example of a risk tolerance questionnaire with poor criterion-related validity. In other words, there should be a relationship between what the test says it is measuring and some external criterion (why else engage in the measurement process!?).

Criterion-related validity studies involve relating scores on a test to some kind of outcome measure. Psychometricians will typically use two strategies when conducting these types of studies.

The first strategy involves ‘predictive studies’, which involve testing clients at one point in time, then measuring those same clients on some other (but related) outcome at a later point in time, and finally identifying whether there is any correlation between the observations that would provide evidence of validity. For example, predictive studies could include first testing clients on investing composure when they are onboarded, and then later having advisors rate the clients’ behavior during a downturn in the market. Was there a significant, positive correlation between the test scores and the clients’ behavior later? If so, this would be additional evidence of validity. If not, it may be time for a new risk tolerance questionnaire.

Concurrent criterion-related validation studies, on the other hand, constitute a second strategy that demonstrates validity by administering the test to a client at the same time the client provides the criterion or outcome data. A good example of a concurrent study is examining a client’s score on a measure of conscientiousness (the predictor) and relating that score to the client’s current savings rate (the criterion). Most research has demonstrated a statistical relationship between a client’s conscientiousness and savings rate, and these types of studies (collecting test data and outcome measures) can be conducted at the same time.

When choosing a behavioral assessment, it is good practice to review the evidence supporting the validity of the test provided by the test developer or publisher. Does it appear that the test developer made an effort to ensure the content of the test was comprehensive? Are there references to research studies that demonstrate how the test relates to other, similar tests? Are there references to studies that demonstrate the test can anticipate future client decisions or behavior?

There should be evidence that the test developer or publisher worked to conduct relevant research studies that examined the validity of the test. The strength and amount of validation evidence depend somewhat on the application of the test and the ‘stakes’ of the decision. This means that if a test is designed more as a means of understanding attitudes, values, and communication styles, the kind of evidence required for validation may be different than if the test is being used to make decisions about clients (or a client’s investment strategy).

How Do Psychometric Tests Benefit Financial Services And Its Clients?

Regulatory bodies, such as FINRA and the SEC, have attempted to provide some loose definitions and guidelines around measuring risk tolerance, but have not provided guidelines surrounding the measure of psychological risk tolerance specifically or prescribed the best way to measure a client’s willingness to take risks. This leaves advisors having to evaluate Risk Tolerance Questionnaires (RTQs) based on what we call face validity (does this test look like something that I should use?) or how easily risk scores can be connected to portfolio allocation models.

This loose approach of relying on apparent face validity is in stark contrast to how assessments used in the personnel selection process are chosen, as this involves a field where tests and their associated decisions related to hiring are highly scrutinized because of their potential for inappropriate development or implementation (i.e., another field where poor practices can lead to lawsuits!). Multiple institutional bodies (e.g., Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology) and sources of law (e.g., Supreme Court cases like Griggs v Duke Power) have provided stringent guidelines for test development and use in personnel selection, thus giving human resources professionals ways to evaluate the usefulness and applicability of tests for their use in hiring.

Nonetheless, with few similar guidelines for measuring psychological risk tolerance in financial services, relying on well-designed psychometric tests offers advisors a way to ensure they are finding reliable methods to assess their clients, especially since an abundance of less-than-scientific assessments exist in the marketplace and because behavioral assessments, particularly those delivered online and not through conversations in the advisor’s office, can eliminate some of the biases associated with the advisor making judgments on their own (or with the client responding in a way they think the advisor wants them to, which may occur if the client takes a test in front of, or has the questions read to them by, an advisor).

Psychometric Assessments Can Predict How Clients Will React When Markets Decline

When trying to understand or measure unseen characteristics of an individual, psychologists and others rely on a variety of methods and resulting measures to ensure accuracy. This is critical, particularly when advisors use assessments to make decisions about their clients based on the results.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the use of tests to help understand a client’s psychological risk tolerance as a factor (among others) used by an advisor to allocate the client’s investments in a portfolio consistent with the advisor’s determination of an overall risk profile. Understanding psychological risk tolerance can help the advisor have some understanding of how the client will react during a period of market stress (like 2008-2009 or March 2020).

Well-constructed psychometric assessments give advisors an indication of the likelihood that clients can emotionally and psychologically withstand change (particularly a decline) in the value of their investments in the future. Perhaps more importantly, well-constructed tests can help predict which clients might make poor (or rash) decisions during a market downfall.

One of the first psychometric assessments of psychological risk tolerance to demonstrate criterion-related validity was the Grable & Lytton risk tolerance questionnaire. The assessment was designed primarily as a research tool and continues to be one of the gold standards in psychometric test design within financial services. The assessment consists of a three-factor model, although it is typically used to assess only one dimension of psychological risk tolerance. The test has demonstrated both construct and criterion-related validity through multiple studies (Grable & Lytton, 2003). In particular, the test offers insight into investing behavior, showing that investors who score high on the assessment tend to hold a higher percentage of their investments in risky assets, compared to those who score low on the assessment having more invested in less risky investments such as fixed-income investments or cash.

Other commercially available assessments have been designed using the psychometric approach, including Finametrica’s risk tolerance assessment, which has been tested empirically with results published in journals and a full technical document outlining its development and corresponding validation studies.

The DataPoints risk-tolerance assessment, the Investor Profile, was also built using psychometric tools and subjected to multiple validation studies outlined in its technical manual. The Investor Profile is designed to measure a client’s trait, or a stable personality characteristic, related to risk-taking propensity, and like other validated risk-tolerance questionnaires has been shown to predict action during a market downturn, giving advisors an indication of which clients are likely to want to buy, hold, or sell when the market declines.

Contrast the approach taken by these psychometric assessments, which aim to examine a client’s enduring characteristics, or traits, with the approach taken by other assessments which aim to measure a client’s state, or current preference for taking risks (e.g., the day they happen to take the test). Some Risk-Tolerance Questionnaires (RTQs) use an econometric, or revealed-preferences, approach to assess a client’s current state of risk-taking propensity.

Revealed-preferences tests, as the name implies, are designed to uncover a client’s current state of preferences when presented with specific risk scenarios. This is done by presenting test takers with known probability outcomes and inviting them to make a choice of which they'd currently prefer. There are practical benefits to this approach in being able to align current preference for risk with a client’s portfolio (or the advisor’s proposed portfolio). However, whether the scenarios included in this assessment technique correspond to or are adequate representations of the uncertain environments in which investment choices are actually made is unknown.

The key distinction, though, is that by design, revealed-preferences assessments measure a client’s current desires related to risk-taking versus a psychometric assessment of a client’s more stable traits related to investing personality. Therefore, revealed-preferences tests require frequent administrations (i.e., they must be taken again and again over time) because the client’s risk-tolerance ‘state’ can change if there are changes with respect to the markets or the client’s current financial situation (e.g., income level). Because states are temporary and not as stable as traits, it goes without saying that these revealed-preferences assessments may not be able to reliably anticipate future investor behavior (unless, at best, said events happen not very long after the test was administered).

If the intention of the test is to predict future behavior during a market downturn, psychometric assessments of a client’s personality (traits) are better suited to take on that difficult task, to the extent that part of the allocation decision is based on what the client might do in the future. If an RTQ is being used to uncover current risk preferences instead, then the revealed preference approach may be preferred. It is up to the advisor and the firm to determine if state measures of risk tolerance assessment are appropriate or if trait measures better suit their practice.

Psychometric Assessments Can Accurately Identify (Other) Client Personality, Attitudes, And Values

The main application of understanding client characteristics in financial services has historically been in the area of measuring psychological risk tolerance, with multiple companies providing off-the-shelf assessments and many others creating and using their own in-house measures, given regulatory “Know Your Customer/Client” (KYC) obligations.

But today, behavioral assessments is a stand-alone category within the advisor tech world, with tools designed to understand communication styles (like FinancialDNA’s assessment) to those designed to help uncover a client’s wealth-building potential (like the DataPoints Building Wealth assessment).

Perhaps the advisor wants to align their communication based on the client’s personality. A planner may want to measure a client’s money scripts or their past experience with saving, spending, and investing. A financial coach might want to provide guidance to a client struggling to adhere to a spending plan and to help them appreciate a more frugal approach to spending. Firms may want to use assessments to align client and advisor values and personalities in order to improve retention and the overall client experience.

Utilizing behavioral assessments is important especially because of the great impact that client financial psychology can have on spending, saving, and investing decisions. In practice, these decisions may be driven by client traits that may not always be readily apparent or are difficult to uncover, but they can be identified with a psychological assessment. In other words, such tests can play an important role in not only helping advisors to understand client personality, but also to better predict what clients might do in the future.

We know, for example, that clients who are conscientious tend to be better at managing finances at home. Clients who are more agreeable may have a harder time saying no to spending when they are with others. Clients with higher emotional stability tend to be less impacted by market fluctuations. Characteristics like frugality and a general propensity to ignore the buying behaviors of others predict outcomes like a client’s net worth regardless of age or income. There is a clear need for advisors, who have the critical responsibility of helping their clients achieve financial and life goals, to understand how the client’s unique personality could thwart the best-designed financial plan or investment strategy.

Similarly, researchers have shown that having money arguments early in one’s marriage is one of the strongest predictors of divorce. Thus, if an advisor can identify differences in financial attitudes and values of a client couple early in the client-advisor relationship, they may be able to proactively address these differences either through their own conversations with and guidance offered to the client (or with the help of a network of other professionals).

While the advisor could rely on their own judgment of their clients’ potential values and attitudes (which, as we discussed earlier, may be impacted by the advisor’s own biases and limited, direct interaction with her clients), a well-developed assessment of financial attitudes could instead provide the advisor with a more accurate understanding of each client’s attitudes without having years of interaction with those clients and, at the same time, eliminate potential biases in how the clients are viewed.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that the CFP Board recently updated its Principal Knowledge Topics to include the “Psychology of Financial Planning.” The first component of this new area is Client and Advisor attitudes, values, and biases. In essence, this subcomponent covers much of what makes clients unique – their personalities.

What To Consider When You Need To Find A (Psychometric) Test

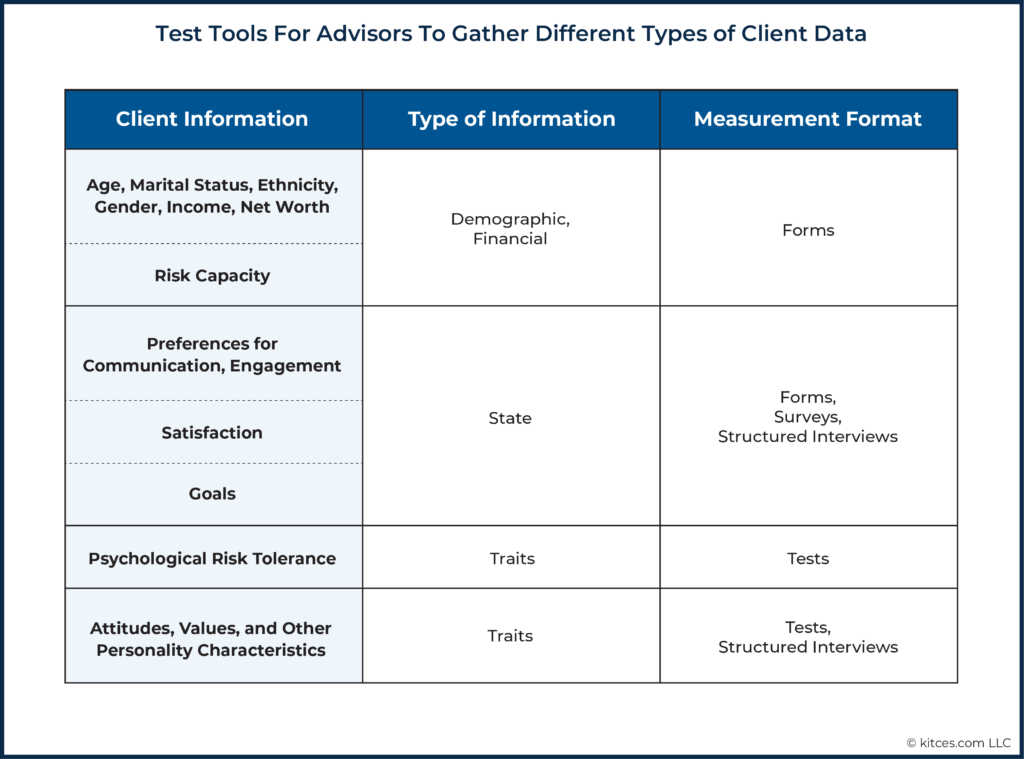

The benefit of using a test is in understanding characteristics about clients that are difficult to measure any other way. In other words, psychological tests are most applicable when you want to know something about a client that is unseen and difficult to measure (back to the example of not using a single question for measuring optimism), and when accuracy and efficiency are required. It goes without saying, though, that there are many instances when other tools may be used to gather information from clients.

Do You Really Need A Test, Or Will A Single Question, Form, Or Survey Do?

To determine whether a (well-designed psychometric) test is necessary, or if a simpler, less expensive tool may be sufficient, it is critical for advisors to know specifically what it is they want to examine. Here are a few examples of some tools and when they can be useful for advisors.

Single Questions Or Forms

Single questions or simple forms can make sense when the advisor wants to gather demographic data or more stable information about a client. Age, marital information, and other demographic information about clients can easily be gathered with forms or questionnaires that do not require the more stringent requirements associated with the development of psychometric assessments.

Likewise, preferences for communication (e.g., how often the client would like to receive communications and by what method) are also candidates for single questions on a general onboarding form. Financial planning and client onboarding software provide many of these forms.

Surveys

Surveys are most applicable when trying to understand group-level information about sentiment. How do your clients feel about your services? How do they feel about the communication they receive? Is there a gap between the services you provide and what they need?

There are myriad best practices for designing and implementing surveys, as well as software to conduct those surveys, but they are best used as part of a clear client experience and retention strategy. Group-level data can be used to help identify new services to provide, ways to improve communication, and other broad, firm-level insights. Individual survey results, such as those gathered from former clients, can be used to improve the client experience by identifying areas for improvement.

The frequency of surveys, number of questions, and outcomes of any survey should be considered before implementation.

Interviews

Client interviews, and particularly structured interviews, are best used to establish a relationship with the client while simultaneously trying to understand their past experiences, current lifestyle, or future goals. Structured interviews can be designed to measure specific areas, just like an assessment.

Although they are less efficient in nature, interviews have the benefit of direct interaction with the client (or prospective client). Thus, they can serve a dual role not only by providing a structured way to gather important data, but also by establishing rapport and building trust with the client. The Kinder 3-question method is an example of a structured interview guide that has a clear rationale of helping the client clarify his most important life priorities, and uses clear procedures that involve asking three specific questions during the interview.

Depending on the type of information the advisor wants to collect, there are a variety of tools – in addition to tests – that can effectively help advisors gather the data that they need. Generally, tests aren’t necessary when advisors seek information that is demographic in nature or related to the client’s temporary state of mind. When the type of information sought deals more with psychological traits or personality characteristics, however, tests may be a much more valuable method in capturing relevant information for the advisor.

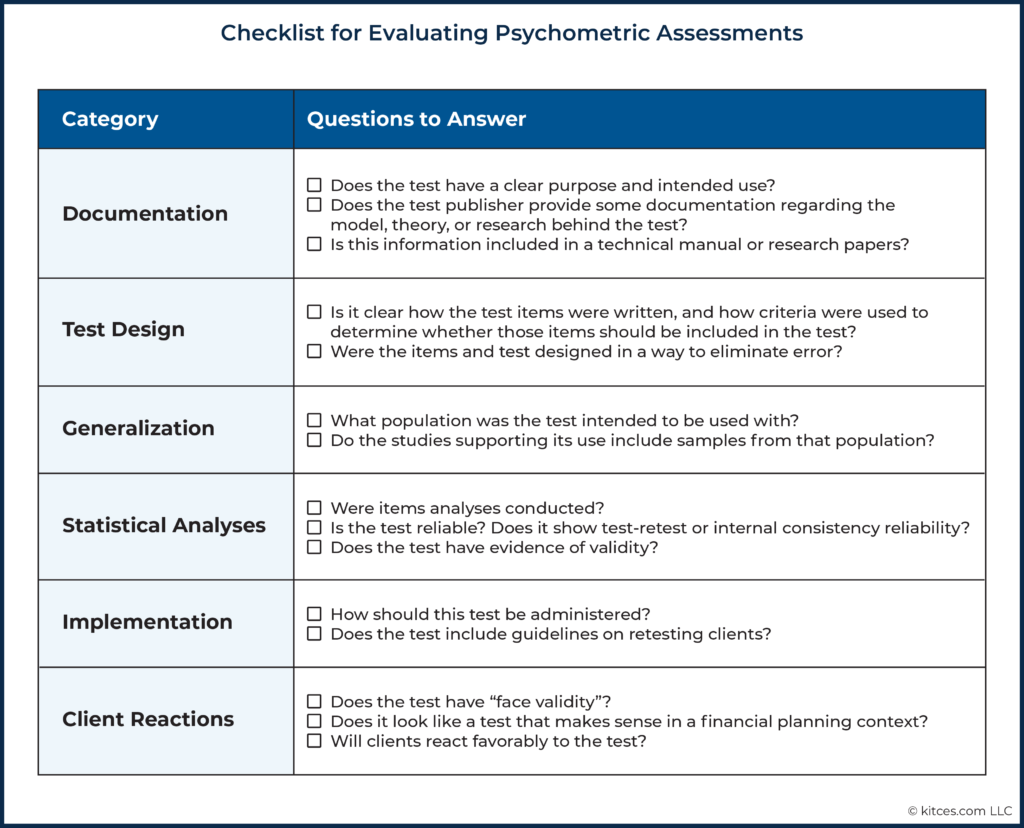

Key Considerations When Choosing A Psychometric Assessment: A Checklist For Advisors

Psychometric tests are the ideal tool to assess a client’s personality efficiently and accurately. Because there are few guidelines or regulatory requirements for how these tests should be developed or used, however, advisors are left to undertake the process of vetting the test provider and the test. Similarly, pop psychology tests, like a Cosmo test, are typically more entertaining for the client (and for us!) than those that are well designed.

Before investing time and resources in adding an assessment to your practice, review the test you are considering in light of the questions below.

The way clients make spending, saving, and investing decisions is tied to personality. Having an accurate measure of a client’s personality can help advisors understand the client and the kinds of financial decisions they may make in the future. However, accuracy in measuring these unseen client characteristics requires a scientific approach to test development.

Scientifically created (psychometrically valid and reliable) tests provide advisors and their clients with a way to (as accurately as possible) understand their attitudes, values, and personality when it comes to financial management, risk tolerance, and other critical characteristics that ultimately can help the advisor better communicate with her clients as well as provide advice that is more personalized. Of even greater importance, psychometric tests can aid in making potentially life-altering decisions about a client’s investments or the service provided to a client. Because of the nature of these decisions, rigor in test design is critical.