Executive Summary

Real estate investors have long enjoyed a number of unique tax benefits, from the tax deductibility of depreciation, to the ability to defer capital gains with a like-kind 1031 exchange. And beyond these core tax benefits of real estate investing itself, Congress has, from time to time over the years, provided additional tax incentives for particular types of real estate development opportunities, as a way to further guide where real estate developers may direct their capital. The latest version, created under the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, is the so-called Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF), which offers some especially unique tax benefits for those who are willing to invest in certain low-income areas designated as "Qualified Opportunity Zones".

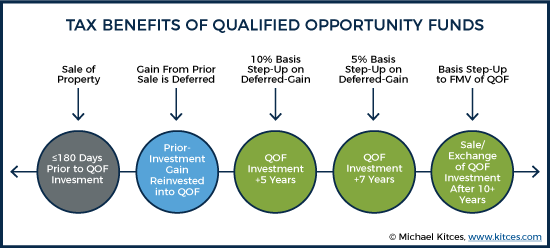

Specifically, investing into a QOF offers the ability to defer tax on capital gains from the sale of existing property that are reinvested within 180 days into a QOF (including not only a rollover of real estate proceeds akin to a 1031 exchange, but even allowing the rollover of capital gains from intangible assets like stocks), subsequent basis increases on deferred capital gains reinvested into a QOF after five years (and again after seven years), and the complete elimination of capital gains tax on growth attributable to gain reinvested in a QOF (if the QOF is held for at least 10 years).

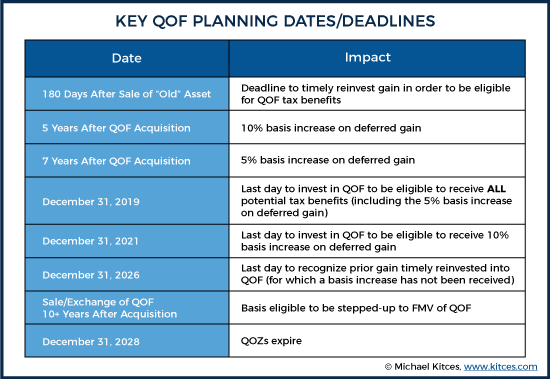

The caveat, however, is that, in order to receive the full array of QOF benefits, the latest date (according to the current tax code) that gains on the sale of assets can be invested into a QOF is December 31, 2019. Past that date, investors will begin to at least partially lose out on basis increases and, thanks to what’s widely assumed to be poor drafting, potentially lose out on other future tax benefits as well. Furthermore, the deferral of the gains on the funds used in the initial investment isn’t perpetual. Gains timely reinvested into a QOF will become taxable (except for any basis increases received after years 5 and 7) at the end of 2026 (or when the QOF is sold, if sooner).

Meanwhile, despite the attractive tax benefits, advisors should exercise caution and perform their normal investment due diligence before jumping in with both feet. Bad investments with good tax attributes are, at the end of the day, still bad investments. Questions such as “What are the management team's qualifications?”, “What are the expenses to investors of the fund?” and “What sort of assets (which, by their very nature, are illiquid) will the fund be targeting?” are all essential to answer. Not to mention the actual merits and growth or income opportunity of the particular real estate investment itself.

Nonetheless, investors who have sold appreciated assets within the past 180 days, or plan to do so in the near future, should evaluate the merits of investing into a QOF. However, the reality is that many investors’ tax planning needs will be better served by using existing strategies, including 1031 exchanges, charitable trusts, and simply holding on to existing assets – all of which may provide tax benefits, including indefinite tax deferral, and the opportunity for a future step-up in basis at death that a QOF does not provide.

In December of 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was signed into law by President Donald Trump, bringing about the largest rewrite of the Federal Tax Code in more than thirty years. While a handful of changes, such as the new lower income tax rates, Section 199A qualified business income (QBI) deduction, and state and local tax (SALT) tax deduction limitation, have received the lion’s share of the headlines, other less-publicized changes may have a larger impact for certain investors/taxpayers.

One change that has largely flown under the radar, but which may prove to be of significant value to some investors, is the Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF). QOFs are the latest in a line of potential tax benefits that, historically, have been used to encourage investment in certain – typically low-income – geographic areas. Previous provisions created with a similar purpose include the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), which was first introduced as part of the Community Renewal Act of 2000, and was last extended through 2019 by the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015.

What Is A “Qualified Opportunity Zone” (QOZ)?

As of the 2010 decennial census, there were over 73,000 census tracts within the United States. These tracts, which generally have a population between 1,200 to 8,000 persons, are “permanent statistical subdivisions of a county or equivalent entity that are updated by local participants prior to each decennial census as part of the Census Bureau's Participant Statistical Areas Program.”

Notably, nearly 32,000 (or over 40%!) of these census tracts are characterized as low-income communities (LICs), defined by IRC Section 45D(e) as an area in which the poverty rate is at least 20%. In addition, a census tract located outside of a metropolitan area will qualify as an LIC if the median family income does not exceed 80% of the statewide median family income. And a census tract located within a metropolitan area will also qualify as an LIC if the median family income does not exceed 80% of the greater of the statewide median family income or the metropolitan area median family income.

It is these LICs that are the core of the new “qualified opportunity zones” tax preferences. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act authorized each state, along with the District of Columbia and the various U.S. territories, to nominate the greater of 25 qualifying (LICs and certain non-LIC contiguous tracts) census tracts, or an amount of similar qualifying tracts equal to 25% of the LIC census tracts within the state, as “qualified opportunity zones.”

Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act itself was just passed in late 2017, this nomination process only recently concluded earlier in 2018, and the IRS has since certified the full list of qualified opportunity zones. The final list was published on July 9, 2018 in IRS Notice 2018-48 (within Internal Revenue Bulletin 2018-28), and is also available as a downloadable and sortable spreadsheet. You can also view the certified QOZs visually using this interactive map. (Note: To easily view QOZs, click on the “layers” icon, and make sure that only the boxes for “Qualified Opportunity Zone Tract” and “State” are selected.)

Once a census tract has been designated as a QOZ, it will continue to remain as such until the end of the 10th calendar year beginning on or after its designation. As such, the current group of QOZs will retain that status until December 31, 2028.

What Is A Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF)?

To encourage development and new construction in LICs, Congress authorized the creation of Qualified Opportunity Funds. The appeal of investing into a Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF) is that investors reallocating gains from other investments into such funds may qualify for a number of substantial tax breaks (described further below).

The name “Qualified Opportunity Fund” may conjure up thoughts of mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, and other registered investments, but the reality is that QOFs are substantially easier to create and maintain than such investments. A QOF is simply a corporation or partnership for federal tax purposes, which is created for the purpose of investing in qualified opportunity zone property and holds at least 90% of its assets in “qualified opportunity zone property.” Such property consists of the following:

- QOZ stock – QOZ stock must be acquired at its original issue from the corporation solely for cash, and substantially all of the business’s tangible assets (owned and leased) must be QOZ property.

- QOZ partnership interest – Such interests must be acquired at its original issue from the partnership solely for cash, and substantially all of the business’s tangible assets (owned and leased) must be QOZ property.

- QOZ business property – Tangible property acquired after December 31, 2017, which is first used within the QOZ after acquisition by the QOF, or which is substantially improved by the QOF after acquisition. To “substantially improve” property, a QOF must increase the basis of the acquired property by an amount that exceeds the initial basis (effectively more than doubling its basis) within the 30-month window following acquisition.

Or stated more simply, a Qualified Opportunity Fund is simply a business entity that invests in tangible property (most likely real estate and similar development projects) within a Qualified Opportunity Zone, in which investors can participate by putting their own investment assets into the QOF to be invested accordingly.

Tax Benefits Of Investing In/Via Qualified Opportunity (Zone) Funds

In order to promote investment into QOFs (and the low-income Qualified Opportunity Zones they are meant to help develop), Congress layered a number of tax benefits into the QOZ/QOF rules. Notably, there are three primary tax benefits available to investors, which cumulatively have the effect of allowing them to defer, reduce, and even eliminate various capital gains.

Using Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) For Tax Deferral of Prior Gain

The first major benefit that a taxpayer is eligible to receive for investing in a QOF is a deferral of prior gain. Under IRC Section 1400Z-2(a)(1), an individual is eligible to make an election to defer the gain on the sale or exchange of property (as long as it was to an unrelated party), to the extent that the gain is reinvested into a QOF within 180 days of the sale/exchange of the gain-producing investment.

Notably, there is no requirement that the gain be attributable to any specific type of asset, such as real estate. Rather, gain on “any property” (including real estate, but also portfolio gain on stocks, mutual funds, ETFs, etc.) is eligible for this special treatment, by moving the proceeds of a sale into a QOF that will invest in QOZ projects. Furthermore, there is no limit on the amount of gain that can be deferred in this manner.

Once a proper and timely election to defer gain reinvested into a QOF has been made (the precise mechanics of how investors will make the election is not yet known, but the IRS has indicated, in FAQ posted to its site, that the election will be made on the tax return filed for the year the gain would otherwise be included in income), the gain will continue to remain deferred until the earlier of when the QOF is sold or exchanged, or December 31, 2026. Thus, an individual timely reinvesting gain from a prior asset sale on December 31, 2018 could potentially defer gains for up to eight years, while an investor making a similar investment on December 31, 2024 would only be able to defer gains for up to two years.

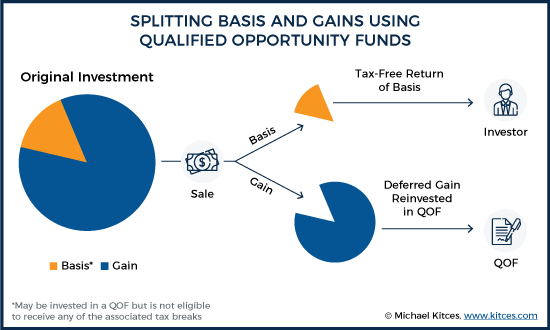

It is also important to note that the ability to defer gain reinvested into a QOF does not require that an investor reinvest both the gain and the cost basis attributable to property sold/exchanged. Rather, after a sale of property, amounts timely reinvested into a QOF can be used to defer the capital gains attributable to that sale on a dollar-for-dollar basis. Thus, unlike other capital-gains-deferral strategies, such as a 1031 like-kind exchange for real estate or a 1035 exchange for annuities, an investor using this approach can bifurcate their cost basis and their earnings, “pocketing” the tax-free basis, and reinvesting only the gain into the QOF! In fact, for reasons described in greater detail below, this will often be the optimal way for an investor to fund a QOF!

Example #1: Nora purchased $100,000 worth of Going Up, Inc. stock 20 years ago. The stock has since increased in value to $1.1 million. Nora would like to liquidate her stock, but does not want to pay the capital gains tax associated with the sale at this time.

To accomplish her goals, Nora could sell her $1.1 million dollars of Going Up, Inc. stock, and reinvest only the $1 million of gains into a QOF. Thus, Nora could “pocket” her original $100,000 investment (into Going Up, Inc.) tax-free to use for living expenses or another investment, and defer the capital gains tax on her $1,000,000 of gains until as late as 2026. (Note: If Nora were to hold the QOF investment for five years or longer, the $1,000,000 total of original capital gains would also be further reduced via basis step-ups, as discussed below.)

Basis Step-Ups On Gain Reinvested Into Qualified Opportunity Funds

The second major tax benefit available to certain QOF investors is a duo of basis increase step-ups on the deferred-gain reinvested into a QOF.

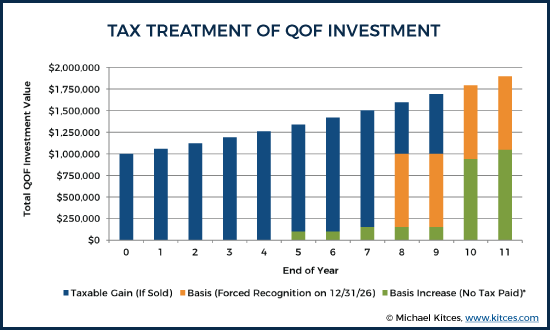

Specifically, IRC Section 1400Z-2(b)(B)(iii) dictates that after an investor has held a QOF for five years, they are able to increase their cost basis in the QOF by 10% of the original deferred gain they invested. Similarly, IRC Section 1400Z-2(b)(B)(iv) states that after an investor has held a QOF for seven years, they are able to increase their basis in the QOF by an additional 5%. Thus, not only does timely reinvesting the gain from a prior investment allow an investor to defer the gain from a prior investment, but thanks to the basis increases that may also be received, an investor can actually reduce the amount of that gain that will ultimately be taxable by 15% of the gain itself!

It is important to note that these basis step-ups apply only to deferred gain that is timely reinvested into a QOF. Gain attributable to the growth of the QOF itself does not receive step-up in this manner (but may separately be eliminated entirely, as described further below).

Example #2: Recall Nora from our previous example, who after selling her Going Up, Inc. stock with a basis of $100,000 for $1.1 million, reinvested only the $1,000,000 of gain in a QOF. Suppose that Nora’s sale of Going Up, Inc. stock took place on September 1, 2018, and that her investment into the QOF fund took place on September 31, 2018 (well within the 180-day window). If Nora were to hold her QOF investment until October 2023 (past the five-year holding period anniversary on September 31 of 2023), during which the QOF itself appreciated to $1.3M, she would be able to increase her basis in the QOF by 10% of the original gain invested, giving her a basis in the QOF of $100,000 ($1,000,000 x 10% = $100,000) and a total gain of $1.2M (including $900,000 of the original gain after basis increase, plus $300,000 of gain that has occurred within the QOF itself).

If Nora were to hold on to her QOF for an additional two years, until October 2025 (for a total of seven years since purchase), when the QOF had appreciated further to $1.4M, she would be able to increase her basis by an additional 5% of the original deferred gain, bringing her basis to a total of $150,000, and her total gain to $1.25M (including $850,000 of original gain remaining, and $400,000 of appreciation with the QOF itself).

Assuming that between capital gains tax, the 3.8% surtax on net investment income, and state income taxes, Nora’s average combined tax rate on capital gains is 25%, the $150,000 (15%) total increase in basis will save Nora $37,500 ($150,000 x 25% = $37,500) of income taxes.

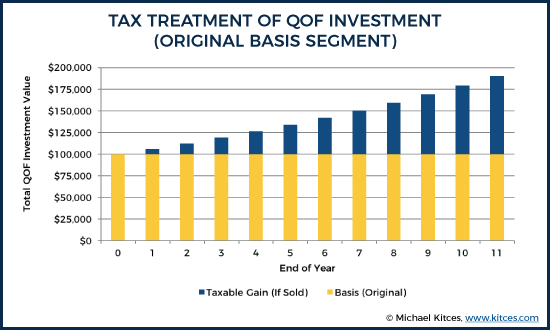

No Tax On Post-QOF-Acquisition Gain (Attributable To Deferred Gain)

The third and final substantial tax benefit available to QOF investors is the ability to completely eliminate any and all post-QOF-acquisition gain by electing to make the basis of the QOF equal to its fair market value at the time it is sold/exchanged. Only long-term QOF investors will be eligible for this benefit, however, as in order to be eligible to make the election, an investor must hold the QOF for at least 10 years.

While this break can eliminate an investor’s capital gains tax on gain attributable to the QOF, it does not allow an investor to eliminate the tax on prior gain reinvested into a QOF. Recall that the deferral of prior gain reinvested into a QOF is taxable upon the earlier of when the QOF is sold/exchanged, or December 31, 2026. Thus, the latest possible time at which prior gain will become taxable is December 31, 2026… which is well before a QOF investor could possibly “hit” the 10-year mark. Therefore, all QOF investors who reach the 10-year mark will have already passed the December 31, 2026 (last possible) date for prior gain recognition, and will have already paid tax on that gain, leaving only the gain attributable to the growth of their QOF investment left to potentially eliminate.

Oddly, this benefit is only available for post-QOF-acquisition gain attributable to previously deferred gain timely reinvested into a QOF. While there is nothing preventing an individual from investing “fresh capital” or the basis of previously liquidated investments into a QOF, any gains attributable to investments of basis are not eligible for 10-year-step-up-in-basis-to-fair-market-value-at-sale/exchange. Frankly, for a Congress whose stated intent was to encourage investment into low-income communities, this seems like a strange choice. Nevertheless, it is the rule.

Example #3: Recall, once again, Nora from our previous example, who after selling her stock with a basis of $100,000 for $1.1 million, reinvested only the $1,000,000 of gain in a QOF on September 31, 2018. Further suppose that Nora holds the QOF for a total 11 years, at which time she sells it for $1.9 million dollars.

Here, as outlined in the prior example, Nora would receive a pair of basis increases after holding her QOF for five years and seven years, respectively, increasing her basis in the QOF to $150,000 as of October 2025. Just a little over a year later, Nora would reach the December 31, 2026 last-possible-day-for-reinvested-gain-recognition date, and would owe capital gains tax on the $850,000 of remaining gain attributable to her sale of Going Up, Inc. stock.

Finally, in October 2028, Nora would reach the 10-year mark, and would be eligible to make an election to increase the basis of her QOF to its fair market value on the date of sale/exchange (whenever that happens to be). Thus, if after 11 years of holding the QOF, Nora decides to liquidate the investment in October of 2029 for $1.9 million, she could increase her basis to that amount (which presumably would be the QOF’s fair market value), pocketing the $900,000 in gain attributable to the QOF entirely tax-free!

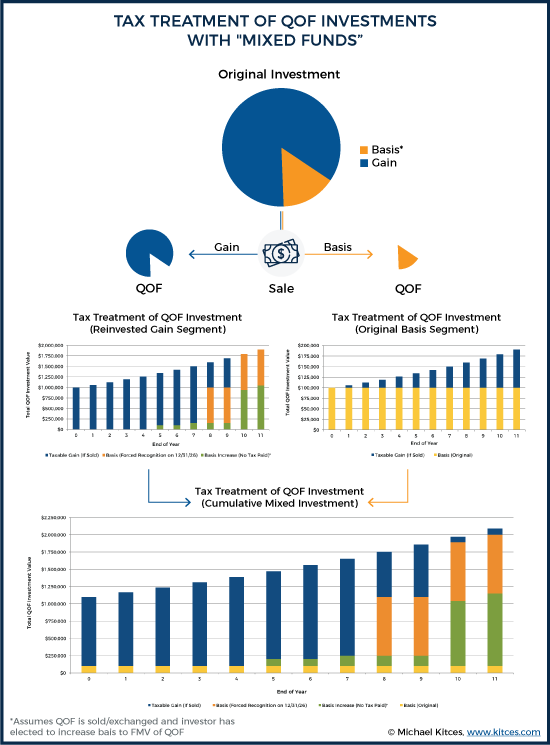

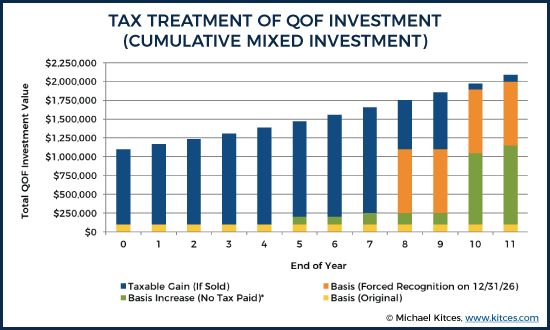

As noted above, the tax benefits associated with QOFs are much more generous for investments of timely-reinvested prior-gain than they are for investments of basis. Whereas, as illustrated in the prior example, “gain-on-gain” growth is completely tax-free after an investor holds a QOF for 10 years, gain on investments of basis are not eligible for the same benefit.

Example #4: Suppose that instead of only reinvesting the $1 million from her sale of Going Up, Inc. into a QOF, Nora, from our previous examples, invested the full $1.1 million ($1 million gain, plus her original $100,000 of basis) proceeds of her sale into a QOF on September 31, 2018. Further suppose that Nora holds the QOF for a total 11 years, at which time she sells it for $2.09 million dollars.

Nora’s investment will be considered an investment with “mixed funds”, which under IRC Section 1400Z-2(e)(1)(A) is treated as two separate investments; an investment of reinvested gain, for which the special tax benefits associated with QOFs are available, and an investment of all other amounts, for which the special tax benefits are not available.

As such, after holding her QOF for five years and seven years, respectively, Nora would be eligible for basis increases identical to those she would have receive if she had only invested the gain from the sale of her Going Up, Inc. stock into the QOF. Therefore, Nora’s cumulative basis in the QOF as of October 2025 would be $250,000, consisting of the $100,00 of basis initially invested, plus the $150,000 of cumulative basis increases to which she was entitled.

Similarly, on December 31, 2026, Nora would reach the last-possible-day-for-reinvested-gain-recognition date, and would owe capital gains tax on the $850,000 of remaining gain attributable to her sale of Going Up, Inc. stock. Thus, her cumulative basis in the QOF would increase to $1.1 million ($850,000 recognized prior gain, plus $250,000 of existing basis.

In October 2028, Nora would reach the 10-year mark, and would be eligible to make an election to increase the basis of her QOF to its fair market value on the date of sale/exchange (whenever that happens to be). Thus, if after 11 years of holding the QOF, Nora liquidated the investment in October of 2029 for $2.09 million, Nora would be eligible for another partial basis increase.

At that time, there would be $900,000 of gain attributable to the previously-deferred gain that was reinvested into the QOF. As such, Nora would be eligible to increase her basis in the QOF by an identical amount ($900,000), bringing her total basis in the QOF to $2 million ($1.1 million existing basis, plus $900,000 basis increase). On the other hand, the additional $90,000 of gain attributable to the $100,000 of basis initially invested would be taxable at that time (at capital gains rates).

Note that the ability of a 10-year QOF investor to adjust their basis to the fair market value of the QOF on the date of sale/exchange is an optional election, not a requirement. This may be important for certain investors who lose money in a QOF, allowing them to preserve potential losses by not stepping down their basis (by not making the election) to the QOF’s lower fair market value at the time of disposition.

Watch Out For Quirks In The Qualified Opportunity Fund/Zone Timeline

There are a substantial amount of dates, deadlines, and holding periods associated with QOZs and QOFs. Unfortunately, the combination of these key chronological markers may produce some surprising results for some investors and prevent others from reaping the full potential tax benefits that QOFs have to offer.

To Maximize Tax Benefits, QOF Investments Must Be Made By December 31, 2019

Gain reinvested into a QOF is eligible for a 10% basis step-up after five years, and an additional 5% basis step-up after seven years (total). However, the latest date at which gain reinvested into a QOF must be recognized is December 31, 2026. That is a “hard” date in the tax code itself, under IRC Section 1400Z-2(b)(1)(B) and is not adjusted based upon a taxpayer’s QOF investment date (or any other factor for that matter).

Thus, absent further future legislation or other adjustments, in order to receive the full benefit of both potential basis step-ups, an investment into a QOF must be made by December 31, 2019. Investments into such funds made after this deadline will reach the December 31, 2026, last-possible-day-for-reinvested-gain-recognition date prior to reaching the seven-year mark, and thus will not be able to take advantage of that opportunity. Similarly, in order to potentially receive at least the 10% basis step-up, an investor must acquire their QOF by December 31, 2021. Investments into a QOF beyond that point will still benefit from the deferral of the original gain (until the end of 2026), and will still be able to claim the capital gains exclusion on the growth on top of that deferred gain… but will lose the 10%/5% basis increase opportunities themselves.

It’s also worth noting that since all gain reinvested into a QOF, other than gain for which a step-up in basis has been received, will be taxable on December 31, 2026, the value of that tax deferral decreases a little bit each day. For instance, a QOF investment made on December 31, 2018, could defer gain for up to eight years, whereas a similar investment made on June 30, 2026, would only be able to defer the reinvested gain for six months.

Guidance Is Needed To Confirm The Tax Treatment Of Post-2019 QOF Investments

There is a legitimate question regarding the potential tax benefits available to QOF investors who acquire such funds after December 31, 2018. Recall that in order to be eligible to step-up one’s basis in a QOF to its value on the date of sale (thus making all QOF-attributable gain tax free), an investor must hold a QOF for a minimum of 10 years. Further recall that in order to qualify as a QOF, a fund’s assets must consist of no less than 90% QOZ property.

That may not seem like an insurmountable problem, but it might be! The legislative text of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act explicitly states that the current group of Qualified Opportunity Zones expires as of December 31, 2028. Furthermore, there is no mechanism to extend the status of the current zones, nor is there a mechanism to establish new QOZs.

If there aren’t any QOZs after December 31, 2028, how can a fund remain invested in QOZ property? And if a fund can’t invest in QOZ property after December 31, 2028, how can it qualify as a QOF after December 31, 2028? And if a fund can’t qualify as a QOF after December 31, 2028, how can an investor hold a QOF for at least 10 years if they acquire the fund any time after December 31, 2018?

Reading the tea leaves and analyzing the relevant Committee Reports, it would seem that Congressional intent was not to limit the full array of QOF tax benefits to only 2018 investors. Nevertheless, what some might call sloppy – or perhaps hastily prepared – legislative text means that further guidance (or a future Technical Correction or otherwise-extending legislation) is needed to know for sure which tax benefits those investing in QOFs in 2019 will be eligible to receive.

Qualified Opportunity (Zone) Funds (QOFs) Vs. Alternative Tax Deferral Strategies

There are clearly a number of substantial tax benefits available for investments into QOFs. And the pressure is suddenly on to identify and invest into these opportunities sooner rather than later, given both the uncertainty of investing into a QOF after 2019 (given the currently-scheduled expiration of QOZs at the end of 2028), and the deadline that investing into a QOF after 2019 will begin to forfeit some of the basis increase opportunities. Not to mention that investors who already made a sale of property with substantial gains in recent months have a 180-day timeline from their prior sale to invest into a QOF in order to defer that gain under the new Opportunity Zone rules.

Nevertheless, investors must be careful to weigh these benefits against other available options, and not fall victim to “shiny object syndrome” (or more generally, to beware of letting the tax tail wag the investment dog).

The allure of tax-deferred gain, basis increases, and elimination of future gain will no doubt attract the attention of many… but for some investors, better options will be available via other, existing strategies, such as 1031 exchanges, charitable trusts and similar vehicles, and the simple step-up-in-basis available at death.

Example #4: Harold is the 60-year-old owner of a commercial building in Manhattan, NY. He inherited the building 40 years ago from his grandfather. At the time, the building was worth $1 million. Over the course of the last 40 years, the building was fully depreciated and thus, has a cost basis of $0.

Meanwhile, during the same timeframe, the building increased in value by 10X, and is now worth $10 million. Thus, if Harold wanted to sell the building, between his capital gains tax, 3.8% investment surtax, and state and local taxes, he’d incur a tax bill of more than $3,300,000 ($10 million x 23.8% federal taxes, plus ~10% state/local taxes = $3,380,000)!

Suppose that Harold, tired of dealing with the hassle of managing the building, has thought about selling the property several times, but has always avoided doing so because of the prospective (and very large!) tax impact.

Now, however, Harold has been “pitched” on the idea of a selling the building and reinvesting the funds in a QOF by “a friend,” and has come to you for advice. Let’s take a look at a few of Harold’s potential options, and how they might play out:

Option #1 – Sell the property and invest in a QOF

Let’s suppose that Harold sells his building and timely reinvests the $10 million proceeds into a QOF on November 30, 2018. Thus, Harold’s gain is temporarily deferred. In December 2023, Harold still owns the QOF and receives a step-up in basis of $1 million (which is 10% of the original $10M gain). Two years later, in December 2025, he receives a similar step-up for another $500,000.

On December 31, 2026, however, the deferral period for Harold’s gain ends. As a result, he will need to pay tax on the remaining $8.5 million of gain attributable to the 2018 sale of his building. The good news is that Harold did get 8 years of additional tax deferral. But the bad news is that Harold already could have had tax deferral by keeping the original property. Not to mention simply holding the original property until death and receiving a step-up in basis then anyway.

By contrast, not only does the QOF force the recognition of the capital gain after 8 years (by the end of 2026, but there is another very material disadvantage of investing in a QOF: gain reinvested into a QOF is considered income in respect of a decedent (IRD), and thus, is not eligible for a step-up in basis.

As a result, even if Harold were to pass away in the next 8 years, he would lose the step-up in basis by reinvesting from his original real estate, into the QOF. This is a substantial potential downside for older investors, and/or others with limited life expectancies, from selling and reinvesting into a QOF, versus simply holding their original appreciated investments (assuming they haven’t been sold already).

Option #2: - Hold Onto The Property (Do Nothing)

A second, logical option for Harold to consider would be to simply hold on to his investment for the time being, and do nothing.

This approach offers at least one dramatic advantage over reinvesting the gain in a QOF… indefinite tax deferral. If Harold desires, he can hold the property until he dies, at which point, his heirs will receive a full step-up in basis on the property. By contrast, if Harold opts for the QOF approach, he’ll have $8.5 million of taxable gain by no later than December 31, 2026 (assuming his QOF does not decrease in value over that time).

Option #3: - Execute a 1031 Exchange

Given the nature of Harold’s existing investment (his dollars are already invested into real estate), another alternative for Harold to consider is a 1031 exchange. In such a transaction, a taxpayer is able to exchange an investment in tangible property (i.e., real estate) for another “like-kind” real estate investment. In this case, Harold might consider using a 1031 exchange to purchase another real estate property easier to manage or cheaper to maintain.

Alternatively, if Harold wanted to get out of the property management game altogether (including potentially hiring such a manager himself), he could consider other 1031 exchange options. Harold might, for instance, consider exchanging to invest in property using a tenants-in-common (TIC) registration alongside other investors who will take on the management role. Alternatively, Harold could make a 1031 exchange and purchase an interest in a Delaware Statutory Trust (DST), which, under Revenue Ruling 2004-86, are treated as direct property interests eligible for 1031 treatment.

Relative to investing in a QOF, the 1031 exchange is disadvantaged by the fact that there are no basis step-ups available during Harold’s lifetime (which is also true if Harold does nothing and holds onto his property). Furthermore, future growth attributable to the exchanged-for property will be taxable if Harold liquidates this investment within his lifetime.

On the other hand, this approach also offers the benefit of indefinite tax deferral. Harold can hold the newly-exchanged-for property until he dies, at which point, his heirs will receive a full step-up in basis on the property. Similarly, if Harold chooses to do so, he can engage in future 1031 exchanges, changing his investment yet again, but continuing to maintain tax deferral. By contrast, if Harold opts for the QOF approach, he will have $8.5 million of taxable gain by no later than December 31, 2026 (assuming his QOF does not decrease in value over that time).

Option #4: - Utilize A Charitable Trust

A fourth option for Harold to consider would be the use of a charitable trust. This could be a particularly attractive option for Harold if he wanted to diversify his holdings away from real estate but maintain tax deferral. The precise nature of the benefits and drawbacks of this approach would depend upon the type of charitable trust (a lead trust or a remainder trust) that Harold elects to use. Nevertheless, benefits of this approach might include ongoing tax deferral, a sizeable up-front income tax deduction, and the ability to rebalance into a far more diversified portfolio than would be possible via either a 1031 exchange or through the use of a QOF.

Of course, to reap these benefits, Harold would have to contribute the building to the charitable trust, thereby diminishing his control over his principal.

Qualified Opportunity (Zone) Funds represent a new tool in the advisor arsenal, and one that can provide investors with a substantial number of tax benefits, especially for those who have recently sold an investment for a substantial capital gain and want to avoid the tax liability by rolling the gains into a QOF within 180 days. Nevertheless, prior to making such an investment into a QOF, an individual should consider not just the tax benefits of the QOF itself, but whether the QOF is a sound investment in the first place!

Who will be managing the QOF? What type of fees does the QOF charge to investors? What type of assets is the QOF purchasing, and where? What, really, is the actual income or growth potential of the underlying real estate or other investments being made into a low-income area? These “regular” concerns apply to QOFs too!

In other words, as amazing as the potential tax benefits associated with QOF investments may be – with tax deferral, basis increases, and even "forgivable" capital gains – it’s important not to lose sight of the big picture: it’s almost always better to invest in good investments and pay taxes on gains, than it is to invest in lousy investments with tax benefits. Of course, if you can find a good investment that also has good tax benefits… well, that’s a home run. But will QOFs be that kind of investment?

It’s possible, but there are certainly plenty of reasons to approach QOFs with a healthy dose of skepticism. For starters, if investing in low-income communities was that great of an investment opportunity on its own, you’d likely already see investment capital readily flowing into those communities. But in practice, that often hasn't happened - and thus why Congress is now providing tax incentives to encourage such investments - and the unfortunate fact that investment capital has not already been flowing to these areas may speak volumes about the relative merits, or at least the substantive risks, of making such investments.

There are also structural issues associated with investing in a QOF. The underlying assets of these funds must be tangible assets – real estate in most cases – which by their very nature are fairly illiquid. Thus, QOF investors should be mindful of liquidity needs and, given the lack of a track record for QOFs (after all, they were created less than a year ago!), be mindful about relying on a QOF sponsor’s anticipated liquidation strategy/timing that may or may not pan out as projected.

And then there’s the reality that many investors have accumulated most, if not all of their savings in retirement accounts, such as IRAs, Roth IRA, 401(k)s, and other employer-sponsored retirement plans. These assets already have tax deferral, and would also not benefit from any basis increases. As a result, it’s likely that for many investors looking to allocate retirement funds, better options – real estate or otherwise – would be available. QOF investment opportunities are best suited to non-retirement accounts (where they also won't have to potentially deal with UBTI issues that may also apply to QOFs held in a retirement account).

Finally, again, it’s important not to forget that, while QOFs can offer an array of substantial tax benefits, many individuals will still be better off using more traditional tax-planning techniques. Certainly, those investors who have already sold appreciated assets (within the past 180 days) and those who intend to do so in the near future, regardless of the QOF rules, should give QOFs an “honest” look for the ability to roll over that tax gain. But for other investors with no existing desire to sell, simply holding onto an existing, appreciated, and well-performing asset, may be the best option, as growth will remain tax-deferred for as long as the investment is held, and there is no forced tax recognition date on the horizon.

Good article — do you know of any ETF’s that are QOZ qualified? That you can invest in?

Jeffrey,

After the 7 year holding period, and the basis rise os 15%, is it possible to write down existing capital gains with rolled over capital losses?

Dan

Can individual partners and shareholders reinvest in Qualified Opportunity Funds to defer gains flowing from S-corporations and partnerships?

Hi Jeffery,

I’ve been trying to find answer to this but I haven’t seen anywhere so maybe you could answer. Everyone indicates that funds must be invested by end of 2019. Is that just to receive full benefit? If someone invests 2020 will they still get the 5 year reduction in basis and more importantly to 10 year presuming they hold for 10 years. Thanks.

Great info! When you sell a rental property for a long term gain and you have passive losses do you subtract the passive losses off the gain and invest that amount in the OZ fund or ignore the PALs altogether? Thanks

If somebody holding a QOZ passes, can their heirs hold through what would have been 10 years from original investment to not pay tax on the QOZ gains? Know you mentioned about IRD if passing during the QOZ investment timeframe.