Executive Summary

An IRA owner has the right to name whoever they wish to be the beneficiary of their retirement account. However, because Congress did not want to allow IRAs (and other retirement accounts) to continue indefinitely, after the original IRA owner passes away there are required minimum distributions (RMDs) that must be taken by the beneficiary, forcing the account to be liquidated over time.

Fortunately, though, Congress does allow those post-death RMDs to be drawn out slowly over the life expectancy of the beneficiary, at least where the beneficiary is a “designated” beneficiary that is a human being with a life expectancy to be stretched across in the first place. But a significant problem arises in the case of trusts named as beneficiary of an IRA – it’s impossible to stretch out RMDs over the life expectancy of an entity that is just “a piece of paper” and isn’t alive in the first place! As a result, leaving a retirement account to a trust potentially loses the ability to stretch the distributions out after the death of the original owner.

The good news, however, is that the Treasury Regulations actually do allow an IRA inheritance trust in certain circumstances to be treated as designated beneficiaries eligible to stretch post-death RMDs over life expectancy, by looking through the named trust to the underlying beneficiaries and using their life expectancies instead. The caveat, though, is that qualifying for “see-through” trust treatment requires the trust to be drafted properly, consider crucial decisions like whether to be structured as a “conduit” or “accumulation” trust, and at best may still entail the trade-off of less favorable income tax treatment to achieve other financial and estate planning goals!

Treasury Regulations Permit Naming Trusts As (Designated) Beneficiaries Of Retirement Accounts

While often viewed as a “gray” area, the reality is that a trust can absolutely become eligible for designated beneficiary treatment, qualifying as a “see-through” trust where the post-death RMDs are calculated based on the life expectancy of the oldest of the trust’s underlying beneficiaries.

In order to be treated as a "see-through trust" and qualify as a designated beneficiary, though, the trust must meet four very specific requirements, as stipulated in Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A-5:

1) The trust must be a valid trust under state law. This requirement is rather straightforward – the trust must be legally formed under state law. Generally this just means the trust is not a handwritten trust (not permitted in many/most states), has been properly signed and executed as a trust (witnessed, notarized, etc., as required under state law), and does not contain any provisions that would outright invalidate the trust under state law. For virtually any trust drafted by a competent attorney that was legally signed and executed in the first place, this requirement should be a non-issue.

2) The trust must be irrevocable, or by its terms become irrevocable upon the death of the original IRA owner. A revocable living trust that becomes irrevocable upon the death of the owner should qualify under this provision, as would any irrevocable trust that was simply drafted to be irrevocable from the moment it was executed. Notably, while the rules do require that the trust beneficiary be irrevocable (or become so upon death), IRA beneficiary designations themselves remain revocable until death, which means even if an “irrevocable” trust is made as beneficiary of the IRA now, the IRA owner can still “change” the trust by simply creating a new irrevocable trust and changing the beneficiary designation from the “old” irrevocable trust to the “new” irrevocable trust (or alternatively, just get rid of the irrevocable trust altogether if desired). Make sure the trust is properly executed to be a valid trust though (see #1 above), and be cautious about certain joint revocable trusts that may still remain revocable after the first death. Bear in mind that the IRA beneficiary “irrevocable” trust could still be a subsection of another trust that is revocable (as long as the particular sections guiding the trust-as-IRA-beneficiary cannot be revoked after death of the IRA owner), and that the trust could also be a testamentary trust created under a Will that doesn’t even come into existence as an (irrevocable) trust until the death of the IRA owner in the first place.

3) The trust’s underlying beneficiaries must [all] be identifiable as being eligible to be designated beneficiaries themselves. Not surprisingly, the Treasury Regulations require that if distributions are going to be stretched over the life expectancy of trust beneficiaries, that the trust beneficiaries must be identifiable in the first place, which generally means they should either be identified by name, or identified as members of a “class” of beneficiaries that could be identifiable when the time comes (e.g., “my children” or “my grandchildren” would be fine, but “whoever my trustee decides to make distributions to” would not). Notably, embedded in this requirement that all beneficiaries be identified is that they be identifiable as designated beneficiaries, which means they must be individual, living, breathing human beings as beneficiaries; if a charity or some other non-living entity is a trust beneficiary, then the trust will not be able to do a stretch over the life expectancy of the underlying beneficiaries because not all the underlying beneficiaries as designated beneficiaries with a life expectancy in the first place!

4) A copy of “trust documentation” must be provided to the IRA custodian by October 31st of the year following the year of the IRA owner’s death. Under supporting Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9), Q&A-6, the “documentation” requirement stipulates that the IRA custodian must be provided with either a final list of all trust beneficiaries as of the September-30th-of-year-after-death beneficiary determination date (including contingent and remainder beneficiaries and the conditions under which they would be entitled to payments) along with a certification by the trustee that all of the requirements for stretch distribution are met under the trust, or the trustee can simply provide a copy of the actual (irrevocable) trust document itself to the IRA custodian. Notably, while this is a purely administrative requirement, it is a requirement and does have a concrete deadline of October 31st of the year after death that must not be missed.

If the four requirements listed above are met, a trust as IRA beneficiary can qualify as a designated beneficiary, and the post-death RMDs can be stretched, with the caveat that the stretch will still be calculated based upon the life expectancy of the oldest trust beneficiary of the trust (who would have the shortest life expectancy).

Naming A Conduit Vs Accumulation “See-Through” Trust

While the four requirements for qualifying a trust as a designated beneficiary eligible for “see-through” trust treatment are relatively straightforward, and allow the trust to stretch distributions based on the life expectancy of the oldest underlying trust beneficiary, the complication that arises is determining which beneficiaries should be considered on the list to determine who is the oldest in the first place.

Some situations are rather simple. If money is held in trust for the benefit of a spouse and she is the only beneficiary of the trust, then her life expectancy will be used. If the IRA assets will be held in trust for the beneficiary of the spouse but limiting her access to the funds, such that there will be a remainder that goes to the children, the situation is still fairly simple: there are now both current (income) and remainder beneficiaries, but the spouse as parent will clearly be older than the children, so the spouse is still easily determined to be the oldest beneficiary of the trust for purposes of determining the stretch.

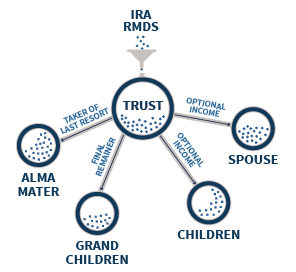

For trusts that will hold property in trust – including, perhaps, the trust’s interest in a decedent’s IRA – for an extended period of time, though, the situation gets more complicated. For instance, if the funds are held in trust where the spouse gets only the income at the optional discretion of the trustee, then when the spouse dies the money continues to be held for the children where they still only get income at the trustee's discretion (and principal remains in place), and then only after the children pass away do the funds go outright to the grandchildren, and if there are no (remaining) grandchildren when the children pass away then the funds go to the decedent’s alma mater as the "taker of last resort" (the beneficiary if everyone else is deceased), the situation is less clear. Should only the spouse be included? Or spouse and children? Or spouse and children and grandchildren? Or spouse, children, grandchildren, and the decedent’s alma mater? The distinction matters, because if the alma mater is included, as a charity it is not a designated beneficiary and could render the entire stretch IRA invalid (as requirement #3 above was that the trust have only identifiable individual beneficiaries who would themselves be eligible for stretch treatment as a designated beneficiary, and a charity doesn’t count!).

For trusts that will hold property in trust – including, perhaps, the trust’s interest in a decedent’s IRA – for an extended period of time, though, the situation gets more complicated. For instance, if the funds are held in trust where the spouse gets only the income at the optional discretion of the trustee, then when the spouse dies the money continues to be held for the children where they still only get income at the trustee's discretion (and principal remains in place), and then only after the children pass away do the funds go outright to the grandchildren, and if there are no (remaining) grandchildren when the children pass away then the funds go to the decedent’s alma mater as the "taker of last resort" (the beneficiary if everyone else is deceased), the situation is less clear. Should only the spouse be included? Or spouse and children? Or spouse and children and grandchildren? Or spouse, children, grandchildren, and the decedent’s alma mater? The distinction matters, because if the alma mater is included, as a charity it is not a designated beneficiary and could render the entire stretch IRA invalid (as requirement #3 above was that the trust have only identifiable individual beneficiaries who would themselves be eligible for stretch treatment as a designated beneficiary, and a charity doesn’t count!).

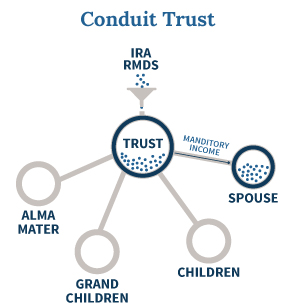

To simplify this situation, Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-7 allows that if the trust requires that all required minimum distributions collected from the IRA will pass through directly and immediately to the underlying income beneficiary, that only the income beneficiary’s life expectancy must be considered. This “conduit trust” rule essentially permits all other subsequent remainder beneficiaries to be ignored in the process of determining the oldest life expectancy, in exchange for the fact that the trust will not be able to accumulate any of the IRA’s RMDs for those subsequent beneficiaries (since they all must pass through immediately each year to the income beneficiary for conduit trust treatment in the first place).

To simplify this situation, Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-7 allows that if the trust requires that all required minimum distributions collected from the IRA will pass through directly and immediately to the underlying income beneficiary, that only the income beneficiary’s life expectancy must be considered. This “conduit trust” rule essentially permits all other subsequent remainder beneficiaries to be ignored in the process of determining the oldest life expectancy, in exchange for the fact that the trust will not be able to accumulate any of the IRA’s RMDs for those subsequent beneficiaries (since they all must pass through immediately each year to the income beneficiary for conduit trust treatment in the first place).

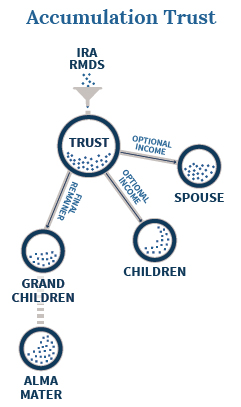

By contrast, any trust that can accumulate the RMDs as they leave the IRA, and might not subsequently pass them through to the underlying beneficiaries until some later date, is deemed an “accumulation” trust where both the current income and remainder beneficiaries must be considered. And in fact, as long as the trust can continue to accumulate RMDs (because there’s not yet any outright distribution), it’s necessary to continue down the line of trust beneficiaries until the point is reached where an outright distribution occurs.

By contrast, any trust that can accumulate the RMDs as they leave the IRA, and might not subsequently pass them through to the underlying beneficiaries until some later date, is deemed an “accumulation” trust where both the current income and remainder beneficiaries must be considered. And in fact, as long as the trust can continue to accumulate RMDs (because there’s not yet any outright distribution), it’s necessary to continue down the line of trust beneficiaries until the point is reached where an outright distribution occurs.

Once the outright distribution is scheduled to occur, no subsequent beneficiaries must be considered for life expectancy purposes under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-7(c)(1), because at that point any future beneficiaries would not actually have a legal right unto themselves but would simply be “mere successors” to the actual stretch beneficiaries. Thus, in the context of the earlier example, the alma mater would not need to be considered as a beneficiary, even under the accumulation trust rules, because the outright distribution was to the grandchildren and so the charitable institution further down the line is considered a mere successor interest to the grandchildren and not a beneficiary unto itself.

Planning Issues And Opportunities With Naming An IRA Inheritance Trust As Beneficiary

Notably, the idea of a trust being a “conduit” or “accumulation” trust for the purposes of being a beneficiary of an IRA and getting stretch treatment is separate from the otherwise-intended purpose of the trust. In other words, it’s not that a trust is a “conduit” or “accumulation” or “bypass” or “QTIP” trust. Instead, the point is that a bypass or QTIP trust named as an IRA beneficiary could be of the conduit or accumulation type depending on how distributions are set to occur under the terms of the trust (and the IRS has in fact issued specific guidance about how to coordinate between QTIP income provisions and conduit trust treatment under Revenue Ruling 2006-26).

Nonetheless, the complexity that arises – particularly around the creation of accumulation trusts, and ensuring that there is not a beneficiary somewhere in the list of potential beneficiaries that might either diminish or entirely ruin the post-death RMD stretch treatment – necessitates having an attorney who truly understands the rules, the coordination between the IRA rules and other trust drafting requirements (e.g., for a QTIP trust), and can navigate appropriately.

Of course, the “simplified” solution to minimize trust drafting problems is to simply have all trusts that will be the beneficiary of an IRA structured as a conduit trust, which ensures that as long as the conduit income beneficiary is an individual, that person’s life expectancy can be used to stretch the IRA. However, from a practical perspective, the challenge is that most of the reasons in which trusts as most appropriate as an IRA beneficiary are the exact situations you would not want to make it a conduit! For instance, if the goal is to shelter the IRA assets from the surviving spouse’s estate for estate tax purposes, pushing through every RMD into the spouse’s estate may just exacerbate the problem, and instead the best thing to do would simply be to have the funds distribution from the IRA to the trust and stay in the trust (which makes it an accumulation trust!). Similarly, if the purpose of the trust is to put a barrier between the beneficiary and the money – for instance, if the beneficiary may be irresponsible with the money, has creditor protection issues, wants asset protection after the recent Clark vs Rameker Supreme Court case that determined inherited IRAs are not otherwise protected assets, etc. – the whole point is to not just push all the money through from the IRA to the trust and immediately to the beneficiary (which puts it back in the beneficiary’s hands for spending or creditors!).

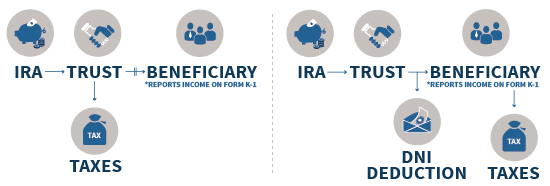

Unfortunately, this dynamic means that not only will trust beneficiaries of IRAs often “need” to be accumulation trusts for planning purposes, but notably the use of an accumulation trust to gather the IRA distributions also generally means that the income tax consequences of the trust will occur at the trust level… which means being subject to compressed trust tax brackets that have a 39.6% top tax bracket starting with as “little” as $12,150 of taxable income (in 2014)! By contrast, if the trust passed through the IRA RMDs to the underlying trust beneficiary, the income tax consequences would generally flow through as well – the trust would claim a distributable net income (DNI) deduction to zero out its income, would report the income to the trust beneficiary recipient on a Form K-1, and the beneficiary would then claim the income on his/her own tax return (at his/her own, potentially lower, income tax bracket), as shown below.

As a result, the decision to use a(n accumulation) trust as a beneficiary of an IRA has both complexity and less favorable income tax consequences to balance against the planning needs of using a trust in the first place (whether for post-death control, asset protection, or other purposes). In the case of a Roth IRA, which is subject to the same post-death RMD rules and the associated trust-as-designated-beneficiary requirements, the income tax issues are generally moot (as the Roth RMDs will still be tax-free as long as the requisite 5-year rule for tax-free earnings is satisfied), but because of the tax-preferenced growth is arguably even more important to ensure that the rules are followed to maximize the stretch in the first place. And the rules do apply for employer retirement plans as well, with the caveat that employer retirement plans aren’t necessarily required to offer stretch treatment in the first place (to trusts or any other beneficiaries) and it may be necessary to complete a trustee-to-trustee transfer of the inherited employer retirement plan to an inherited IRA to facilitate a post-death stretch to a trust beneficiary (which is permitted under IRC Section 402(c)(11) created by the Pension Protection Act of 2006, and subsequent legislation under the Worker, Retiree, and Employer Recovery Act of 2008 required that it be made available as an option to non-spouse beneficiaries).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: trusts absolutely can be used as the beneficiary for a retirement account, and if the clear requirements are met the retirement account’s post-death RMDs can be satisfied by stretching over the life expectancy of the oldest underlying beneficiary. However, executing this strategy effectively does introduce some additional complexity into the planning process, and may entail some trade-offs between less favorable income tax treatment and the desired provisions of (and use of) the trust itself!