Executive Summary

Starting a business from scratch is a risky endeavor, in which often those who put money into the business never even see a return of their money, much less a return on their investment. Which can be especially damaging for a founder who sinks their life savings into a business idea that doesn’t work out… or worse, doesn’t have enough money to put in to get a good idea for a company off the ground in the first place.

Fortunately, though, venture capital firms exist to help fund these high-risk entrepreneurial endeavors. Because for a VC fund, it’s not necessary for every company to succeed; the venture fund can be profitable in the aggregate and generate an appealing return on capital by diversifying across multiple startups, leveraging the power of diversification and the fact that the high risk also generates a very high return potential… such that 80% of the returns may be driven by only 20% of the companies, or in the extreme almost all the returns may come from just 1-2 “home run” investment opportunities that become huge.

Yet the challenge of this kind of ultra-high-risk-and-high-return investing is that VC funds will often shy away from viable business opportunities that are not deemed to be “big enough” to be the home runs necessary to make up for all the potential losses of the companies that don’t work out. Or alternatively, may invest into companies but push the founders to take more risk than they actually wanted to… as while a “Go Big Or Go Bust” approach may work for a diversified VC fund, it can be ruinous to the founder that has only their one company to be a part of!

The end result of this dynamic, particularly in a limited-size “niche” industry like financial advisors, is that few venture capital firms – even those focused on FinTech – actually have any interest in investing in advisor technology, where most of the “successful” companies may eventually sold for $10s of millions… but not the $100s of millions, or billions, that most VC firms are shooting for. Thus why investing in B2C robo-advisors – with their potential for 100+ million consumer households – was more compelling to most venture firms than funding the equivalent next-generation onboarding-and-rebalancing-software solutions for financial advisors.

In turn, this has driven the overwhelming majority of advisor technology innovation to be limited to what companies can be created for advisors, by advisors, and often funded by advisors as well – in a world where the potential to earn “bad” 15% - 20% returns for a VC fund are still “great” returns for an individual advisor-as-investor (whose primary alternative is the stock market). From Junxure to Redtail, to Orion and Tamarac, iRebal and TradeWarrior and Red/Black, RiskPro and Tolerisk… most advisor technology innovation is advisor funded.

Accordingly, we’re excited to announce that our own AdvicePay payment processing solution for financial advisors is opening an extension to its prior Seed round, raising up to $2M of capital directly from the financial advisor community (at least, those who are eligible Accredited Investors!). Because in the end, it seems the only way that technology will improve for financial advisors is to invest in making it happen ourselves!

The Problematic Economics Of Venture Capital Investors

Launching a new business is challenging, with some statistics suggesting as many as 90% of new businesses fail within the first 5 years. And while many businesses get “out-competed”, in most cases the reasons startups fail has less to do with the pure competitive landscape, and more about whether they priced the solution appropriately, assembled the right team to execute on the idea, and managed their cash properly. Although according to one recent series of post-mortem failure analyses of startups by CB Insights, the most common reason for failure was simply that the founder created a product or service that seemed a good idea to him/her personally, but simply wasn’t something other people actually wanted to buy and pay for. (I.e., there was no “market need” for the solution.)

Of course, the flip side of this dynamic is that there is arguably no better opportunity for building wealth than being attached to the value creation of a growing business. And the risk that’s associated with growing a business is why it’s able to generate the greater rewards; thus why stocks earn an equity risk premium over bonds, why small cap stocks earn a premium over large cap stocks, and why most of the Forbes “Billionaires” list is comprised of the founders of major businesses (or their heirs).

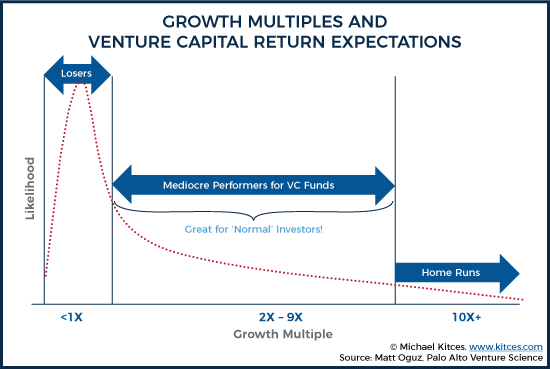

Accordingly, the appeal for venture capital investors is to try to find these “unicorns” – startups that can eventually be worth $1 billion or more. Unfortunately, though, as the name implies, such outstanding startup successes are of mythical rarity, as even with the analytical resources and experience of a venture capital fund to identify potential companies – and the actual dollars they plow into the companies to help them succeed – it’s estimated that 3/4ths of the startups venture capital funds invest in still fail. And many of the companies that don’t outright “fail” still aren’t worth much in the end, either. As a result, a version of the 80/20 rule applies in venture capital investing as well – more than 80% of the returns come from just 20% of the companies they invest in. And the bulk of the cumulative returns may come from just one or two unicorns (or at least “huge home runs”).

The problem with an assumption, upfront, that the overwhelming majority of the companies a VC fund invests in will fail is that it requires the few that succeed to succeed big, because they have to make up for all the rest that don’t. Thus, the typical rule of thumb is that venture capital investors search for opportunities that could 10X their money in 5 years… a whopping 58% internal rate of return on their investment dollars. Because you need a 58% return on just 20% of the companies to make up for the losses on the other 80%, to generate a “healthy” venture capital rate of return like 15%-20%/year! While a company that “merely” doubles, triples, or quadruples in value over 5-10 years (which is still a 15% to 25% return on that particular investment) is a “mediocre performer”, because while the return of that company may be good, and would be an incredible return for a typical investor, it’s not nearly enough to make up for the high volume of losers that are also inevitably part of the venture capital portfolio’s company mix.

How Misaligned Incentives Can Cause Founders To Fail

From the perspective of a venture capital investor, the high-risk/high-return dynamics are simply a reality of the asset class. The VC investor is at least well diversified across a large number of likely losses and hopefully a few big winners, and to the extent the VC can better identify prospective winners, and manage the potential loss exposure of their losers, the more return potential they have for the venture fund.

And ideally, the VC fund will be able to give effective advice and counsel (and of course, the needed financial capital) for the company to grow more successfully in the first place, turning losers into at least mediocre performers, and a few mediocre performers into home runs. In fact, many VC firms will often take a role on the company’s Board of Directors, specifically to help influence the path of the company, in the hopes of helping to build it towards becoming one of those few “home runs”, and not just a single or double (a “mediocre performer” for the venture fund).

And here, unfortunately, is where venture capital investors begin to part ways with the founders of the companies they invest in.

Because the goal of VC investors is to find those few home runs, and encourage the founders to do whatever it takes to become one of those home runs, and not just a single or double. When for most founders themselves, a personal “home run” is hitting a single or double!

For instance, imagine a start-up company that is initially seeded with $200,000, which the founders use to build an effective minimal viable product (MVP). After 12 months, the company has a couple of employees, and is closing in on $50,000/month (or $600,000/year) in recurring revenue, and decides to go out and raise a $1,000,000 Series A round in exchange for 25% of the company (a post-money valuation of $4,000,000) to hire more sales and marketing staff to accelerate their growth, with the hopes of reaching $300,000/year in revenue (doubling the valuation of the still-growing company at $8M+) 5 years from now.

From the founder’s perspective, building an $8M company, of which the founder still owns 60%-80% (after the seed and initial Series A), is life-changing money. Whether it takes 3 years, 5 years, or 10 years, it’s enough for most people to retire and be “set for life”.

From the VC’s perspective, it’s a “disaster”. Growing from a post-money valuation of $4M to $8M in 5 years is “mere” 14.8%/year compounded rate of return, which might not even hit the VC fund’s target return for the entire fund in the aggregate, and is certainly not enough to make up for the 70%+ of losses. In other words, a “home run” for the founder is barely a decent single for the VC fund.

Which means even if the founder is completely right about the opportunity, and could be entirely successful in deploying the $1M of capital to grow the valuation to $8M in five years… no VC fund will be interested in investing for “just” a nearly 15% rate of return. Instead, they’ll either pass on the deal entirely… or try to convince the founder to build something bigger and bolder that could be worth far more.

“Instead of raising $1,000,000, we’ll give you $2,000,000 of capital to deploy, but you have to use the extra $1,000,000 to hire an additional team of 8 people to expand into two more business lines that have more upside potential,” says the VC investor, in the hopes that the company can grow to not just $300,000/month in revenue, but $1,000,000/month in 5 years, and sell as a hyper-growth company for 4X revenue or a $50M+ valuation. Because that is a 12X+ growth factor over the current valuation, and gives the VC investor his/her desired rate of return.

Except the challenge is that the founder is now “compelled” to take on $1,000,000/year in extra ongoing staffing/salary commitments, to run two new business lines the founder may or may not have wanted to build in the first place! And if the new business lines don’t work out extremely well, the company may be running out of money in 18-24 months as it rapidly burns through cash… even if the original solution the founder created in the first place is still selling well in the marketplace. For which the founder may be then compelled to try to raise even more now-toxic venture capital to chase more growth at ever-decreasing marginal returns… which could lead to a total bankruptcy a year or two after that if growth doesn’t turn around.

In other words, the founder could be entirely right about the original business opportunity, and what it takes to make it successful for the founder and the business (e.g., a company that is worth $8M in the future by doubling down on its core solution), but the needs of the VC investor to make it “$50M+ or bust” takes the company in a different (and much more high-risk) direction. Which is fine for the VC investor – who already anticipates that 70%+ of their portfolio companies will fail.

For the founder, however, the misaligned goals of the venture capital investor turns what a company that was on a solid trajectory to someday be an $8M business into one with a 70%+ chance of being worth $0!

Why Venture Capital Economics Have Stifled Advisor FinTech Innovation

When it comes to advisor technology in particular, the fundamental challenge of attracting venture capital is not merely the fact that the venture fund’s “go big or go bust” may end out being misaligned with the goal of the founders. It’s also that when VC firms are looking for “home runs”, the sheer size (or lack thereof) of the advisor marketplace can make it “not compelling” as an investment opportunity in the first place.

After all, the total size of the financial advisor marketplace is about 300,000 advisors (according to Cerulli), and most basic financial advisor software tools (e.g., CRM, planning software, etc.) sell for anywhere from $20/month (appointment scheduling software) to $100/month (financial planning software), or at slightly higher prices when the software is directly attached to revenue-producing activities (e.g., portfolio reporting and proposal tools).

So if a new software solution can gain a “healthy” market share of 10% over 5-10 years (given the highly fragmented financial advisor landscape), and sells its solution at a mid-range price of $50/month for whatever it is they do, the company would generate 30,000 x $50 = $1.5M/month in revenue, or about $18M/year, and ostensibly be valued anywhere from $35M to $50M. Which, in the end, is too small for most venture capital firms to even bother looking.

Because when a venture capital firm raises $50M to $100M to invest into new early-stage companies, then relative to the size of the fund, the firm is likely looking for companies that could be worth $100M+ over their 5-7 year time frame (recognizing that the VC firm may only own 20% of it). Especially since it takes the same amount of time to invest in a smaller company as a larger one – it’s simply more time-efficient to hunt for bigger opportunities. Otherwise, the VC fund runs the risk that even if it finds a relative home run – a company that really does 10X in 5 years – it may not be a big enough home run to move the needle for their total range of investments. In other words, if a VC fund invests $250k into a $1M startup that grows by 20X, it still only produces $5M of actual dollars in the end on the VC’s shares, which isn’t enough for the firm to power its long-term return goals on a $100M base. Better to have invested $2M into a $10M company that could someday be a $100M business.

Which means, simply put, the successful advisor FinTech company that “could” be worth $35M in the future – and would be a “home run” to virtually any startup founder – isn’t capable of being big enough to attract most outside venture capital investors in the first place! And the issue of “small” company size in the advisor technology marketplace really is a real concern for most VC investors, given that most advisor software companies really do sell for $50M or less, including recent transactions like AdvisorEngine buying Junxure CRM ($24M), Envestnet buying FinanceLogix ($32M), Envestnet buying Tamarac (which just crossed over at $54M), along with deals where the exact terms were unknown but the estimated purchase price was far less than $50M, including Oranj buying TradeWarrior, Morningstar buying tRx, and TD Ameritrade buying iRebal. One of the few notable exceptions was eMoney Advisor, that was actually purchased by Fidelity for a healthy $250M (lifted in part by its strategic value to Fidelity above-and-beyond the core eMoney Advisor business metrics at the time).

Thus why the overwhelming majority of advisor technology solutions are “homegrown” software solutions – created by advisors, for advisors, and typically self-funded by those advisor founders (often from the cash flows of their core advisory business), and/or supported by other fellow advisors as investors. This includes many of the most popular advisor software solutions of years past and present, including Junxure CRM, Redtail CRM, ProTracker CRM, Orion Advisor Services, Tamarac, Oranj, iRebal, TradeWarrior, tRx, Rebalance Express by RedBlack, Capitect, Tolerisk, RiskPro, eMoney Advisor, Advizr, and Hidden Levers.

In essence, the desire of venture capital investors to have home runs – and not just home runs, but big home runs relative to their size of their funds – not only leads them to push founders with “go big or go bust” philosophies that may be fine for the VC fund (that is well diversified across multiple investments) but not the founder (who loses what may be their one-and-only-chance for business success), but also drives VC funds away from financial advisor technology opportunities altogether! As we heard from one recent venture fund evaluating our own AdvicePay solution – “we are going to have to respectfully decline… our broad concern is over whether the company can reach the scale we need to see for our target return profile: $50M+ of revenue.”

After all, software built directly for consumers – and reaching for 100,000,000+ households directly – theoretically has a far greater business potential than “just” advisor software solutions. When the Total Addressable Market is measured in the 10s of millions, it’s easier to imagine a path to $50M of revenue, and a “home run” company that could be worth hundreds of millions to a venture capital firm. Even if many of those direct-to-consumer solutions are likely pipe dreams, while B2B industry solutions may have far more sound business models. Because most niche solutions will never be a $100M+ company. While the direct-to-consumer solution that “democratizes” something for everyone may have only a minuscule chance of success… but could literally be a billion-dollar business if it does. The rarity is just accepted as part of the risk of the venture capital investing game. That’s why those companies are named after the mythically-rare unicorn!

Target Market Crowdfunding And Raising Capital For AdvicePay

The end result of these dynamics are that, even when we decided to raise capital for our own first round of capital for our AdvicePay payment processing solution for financial advisors, the majority of the capital came from fellow advisors (and a few VC investors who run “smaller” funds where a successful advisor technology company is still a “success” for their fund).

Because while the prospective returns of successful financial advisor technology companies are deemed “too low” and “too limited” for most venture firms, they’re still very favorable (albeit risky) opportunities for financial advisors themselves, whose primarily alternative are traditional stocks in capital markets (which typically have slower growth rates), and who know the industry and its nuances well enough to be able to evaluate a compelling business opportunity. (Which, similarly, is why most other advisor technology companies were founded by advisors, and funded by fellow advisors.) Recent initiatives like ScratchWorks, a FinTech accelerator program targeted specifically at advisor technology solutions, and both founded and funded by a number of prominent advisory firm executives, is a good case-in-point example of the opportunity that advisors themselves see in advisor technology… even if venture capital firms do not!

Of course, the idea of “crowdfunding” is not new – in fact, it was expanded under the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act in 2012 – and founders have long had the option of raising capital directly from private investors under Regulation D of Rule 506 (as long as they meet the accredited investor requirements). And a number of companies have actually been turning to crowdfunding not only as a means to raise capital for their product or service, but also to validate the demand for it in the first place. After all, if a lot of people in the target market are willing to invest in the company, they will probably be interested in buying its solution, too!

And it’s this dynamic – that advisors themselves are more willing to invest in advisor technology solutions than venture capital firms that, even in the FinTech space, would rather shoot for the next low-probability consumer unicorn than an otherwise-sound B2B niche solution – that has led us to decide that for our own next round of capital for AdvicePay, we’ve decided to raise capital directly from the advisory community!

Accordingly, we’re excited to announce that AdvicePay is now opening up an extension to its seed round to raise up to $2M of capital on a (pre-money) valuation of $6M… by “crowdfunding” directly to the advisory community! For financial advisors who are interested (and who meet the Accredited Investor requirements!), we have posted details about exactly why we’re raising capital to fund the next stage of growth for AdvicePay, the terms for investors, and the business opportunity that we continue to see in the advisor marketplace (and are excited to raise capital to accelerate!)!

Accordingly, we’re excited to announce that AdvicePay is now opening up an extension to its seed round to raise up to $2M of capital on a (pre-money) valuation of $6M… by “crowdfunding” directly to the advisory community! For financial advisors who are interested (and who meet the Accredited Investor requirements!), we have posted details about exactly why we’re raising capital to fund the next stage of growth for AdvicePay, the terms for investors, and the business opportunity that we continue to see in the advisor marketplace (and are excited to raise capital to accelerate!)!

Because in the end, it seems the only way that technology will improve for financial advisors is to invest in making it happen ourselves!

So what do you think? Are the economics of venture capital investment problematic for advisor FinTech firms? Can misaligned incentives actually cause founders to fail? Will the overwhelming majority of advisor FinTech firms always be "homegrown" solutions? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Disclosure: Michael Kitces is a co-founder of AdvicePay.

Leave a Reply