Executive Summary

In recent months, the CFP Board has been buffeted by criticism of its current compensation disclosure rules - built upon a series of definitions that the CFP Board insists have not been changed since the Practice Standards were approved after a public comment process more than 5 years ago, yet appear to be impacting so many advisors that it's difficult to understand how the current way the CFP Board is interpreting its rules is anything but a change from how things once were.

The key point of dispute appears to revolve around the CFP Board's use of its so-called "3 buckets" approach to determining the types of compensation an advisor receives, which looks at what clients pay to the advisor, to related parties, and how the advisor themselves generate income from their employment and ownership interests. In the process, the definition of what constitutes "compensation" has stretched so far that advisors can now be disciplined for failing to disclose types of compensation that don't actually exist because no client has ever actually paid it to anyone, ever!

Accordingly, it's time for the CFP Board to "clarify" its 3 buckets approach to recognize that the fundamental starting point for all types of compensation disclosure should always be what clients actually pay in the first place. The fact that no client has ever actually paid a commission to anyone, ever, should always be a valid defense for an advisor to claim that they are fee-only (and the same should apply to commission-only advisors whose clients have never paid fees, and who are equally in "violation" of the CFP Board's current rules). By fixing its confused and problematic rule, the CFP Board can start to move past its recent compensation disclosure debacles and move the definitions in line with a clear and logical rule that consumers can actually understand, and eliminate the absurd requirement for advisors to disclose (and potentially be punished for failing to disclose) client compensation that doesn't actually exist!

Understanding The 3 Buckets Approach

The basic principle of the CFP Board's 3-bucket approach is relatively straightforward, as articulated in the CFP Board's update on fee-only disclosure webinar.

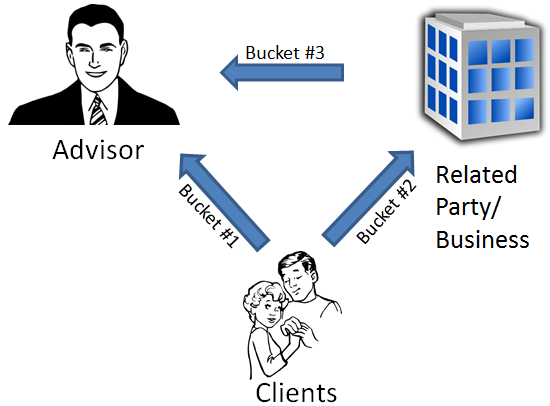

In essence, the 3-bucket approach states that to determine the nature of a CFP certificant's compensation, the CFP Board looks at three different buckets: money that goes from the client to the CFP certificant, money that goes from the client to a related party, and money that goes from the related party to the CFP certificant. This is illustrated in the graphic below.

Accordingly, if the client pays a commission to the advisor, clearly the advisor must disclose the compensation. If the client pays a commission to a related party to the advisor, likewise the advisor must disclose the commission compensation. And if the advisor has a relationship to a related party (e.g., is employed by or has an ownership interest in) that receives commissions, then the advisor must disclose commissions. In other words, simply put: if commissions are associated with the compensation derived from any of the three buckets, the CFP certificant cannot be fee-only, and must disclose commission-and-fee compensation.

The Problem With The 3 Buckets Approach

While the 3 bucket approach above may appear to make sense, it creates some very illogical and questionable outcomes in certain circumstances, particularly when the CFP Board looks only to the relationship between the CFP certificant and related parties (bucket #3) in the absence of bucket #2 and the overall situation.

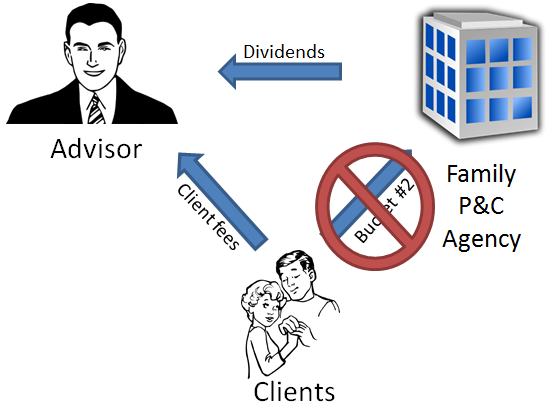

For example, assume the CFP certificant generates personal income in two ways: fees paid directly from a client, and dividend distributions from a separate property-and-casualty insurance agency in which the advisor owns a small interest inherited from a parent (the P&C agency is a family business). Under the 3 bucket strategy, the advisor's compensation types would be as shown below; since there is both a portion that is fees and a portion that is commissions (the compensation that leads to the bucket #3 dividends), the advisor would be required to disclose "commission and fee" compensation.

Of course, there's one notable issue in this compensation disclosure outcome: at no point does any client of the advisor actually pay a commission to the related party (or anyone) at any time! The advisor has no active role in the P&C insurance agency, and simply receives dividend distributions in the same manner that he would if he owned a publicly traded financial services stock (e.g., the many bank and broker-dealer stocks in an S&P 500 index fund). In other words, the advisor is now required to disclose to a client that he is compensated by commissions despite the fact that no client is ever actually intended or expected to pay a commission to any related party (or anyone else) ever!

Certainly, if the client actually did business with the P&C agency (or the advisor tried to direct clients accordingly), then bucket #2 of the 3-bucket scenario would be filled, and clearly the advisor would absolutely need to disclose the (indirect) commissions received. But by ignoring the second bucket, the CFP Board's rules reach a nonsensical conclusion - that advisors are required to disclose client compensation that no client ever actually pays and that doesn't exist in the first place! In fact, if this advisor claimed to be fee-only - because 100% of clients only ever pay fees and don't pay commissions to anyone, anywhere, ever - the advisor could still be publicly sanctioned for failing to disclose commissions under CFP Board rules!

Similarly, because the CFP Board accounts for bucket #3, without regard to bucket #2, the end result is that virtually any ownership interest in a financial entity - such that it constitutes a "related party" by mere ownership alone - could run afoul of the rules. An ownership interest in a bank, broker-dealer, or insurance agency can run afoul of the rules (as was the case with Alan Goldfarb). In fact, a mere ownership interest in an S&P 500 index fund could run trigger a requirement to disclose commissions (since the S&P 500 includes dividends from financial services companies that generate revenue via dividends), especially if the advisor has a significant net worth invested in the S&P 500 (where the dividends from their index fund could equal or exceed their compensation from clients, clearly making it "non-trivial").

Of course, since the CFP Board doesn't even define what is "non-trivial" in the first place, it's not clear when a relatively small ownership interest, e.g., in a family financial services entity, can trigger the rules as well (per the example above). Similarly, if an advisory firm is owned by a parent company that has related entities that are bank or broker-dealer related (e.g., any/every advisory firm aggregator/roll-up firm that has a bank parent company or also owns a broker-dealer subsidiary), it would lose its fee-only status. In fact, in theory just one advisory firm partner who owns 1% of an outside entity that generates some of its income from a commission-related business could taint the entire advisory firm, even if it has multiple partners, a large clientele, and not a single client ever actually pays a commission to anyone! (If a firm with 20 partners has one partner that inherits a 1% interest in a family financial services business, is the entire firm disqualified from fee-only? The answer appears to be yes according to the CFP Board's rules, even if no client even does business with that entity!)

In fact, the common theme to all of these scenarios is that they're all real-world situations of CFP certificants who have already contacted me, where fee-only firms are apparently not permitted to call themselves "fee only" because an "unrelated" party is associated with commissions, and the mere fact of an ownership or employment relationship exists triggers "commission" status even though the entity has no actual relationship to clients themselves and no clients have ever actually paid a commission to anyone, ever, and are not intended to do so!

Simply put, they are all scenarios where bucket #3 is triggered a nonsensical requirement to disclose commission compensation even though it doesn't actually exist, simply based on the balance sheet of the individuals or entities that happen to have an ownership interest in the advisory firm and another party that is "related" by ownership but unrelated to any actual clients.

Fixing The CFP Board's 3 Buckets Rule

So what's the resolution to fix the CFP Board's problematic rule? The key is to recognize that the fundamental purpose of compensation disclosure is to disclose how advisors are compensated by their clients - which means the starting point should always be what clients actually pay to various parties.

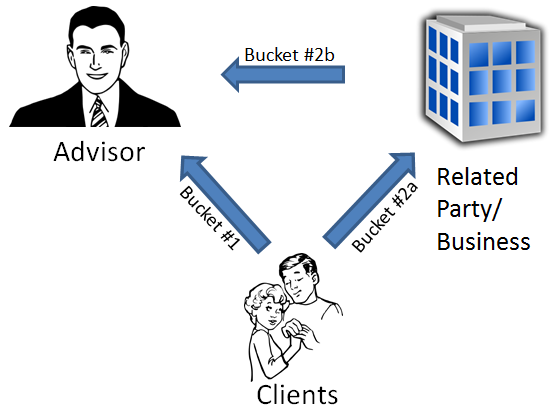

Accordingly, advisors should really only ever have to disclose compensation associated with buckets #1 and #2 - what is the advisor paid, and what is paid to the advisor's related parties? In fact, arguably the original purpose of bucket #3 was simply to recognize that in order to determine whether an outside party is related or not, it must be determined if the advisor is receiving any direct or indirect compensation from that party.

For example, if an advisor refers a client out to TermInsurance.com for insurance needs, the client will technically pay a commission (as it's part of the cost of term insurance), but the commission will be paid directly to the website, and none of that compensation will flow back to the advisor - thus, since bucket #2 will be filled with respect to the transaction, but bucket #3 will not, the party is not actually a related party and therefore the advisor would not be required to disclose commission-and-fee compensation (which makes sense, as the advisor isn't actually receiving any commissions, directly or indirectly, and is referring the business out!). Alternatively, if the advisor referred the client to do term insurance with an insurance agency the advisor owns - which means the advisor would receive indirect compensation for the commissions paid in the form of dividend distributions from the insurance agency - then it would be necessary to disclose commissions, because the advisor is actually receiving a benefit from the commissions that the client paid. (Notably, this appears to be the exact circumstances at hand in the Camarda case, where the advisors claimed to be fee-only but routed clients to do commission business with an entity owned by that advisor.)

What this means is that the real purpose of the 3rd bucket in the 3 bucket rule is determine whether the CFP certificant is receiving a direct or indirect benefit of a commission (or fee) paid to an outside party. In other words, in a world where the term "related party" is actually not defined by the CFP Board, the 3rd bucket essentially creates that definition - a related party is a party that provides a non-trivial direct or indirect economic benefit is paid to the advisor, whether through an employment relationship or an ownership relationship.

Nonetheless, the existence of a 3rd bucket is not proof that the advisor receives commissions, because it fails to establish whether any client ever actually pays any commissions to that party in the first place! It simply creates the potential that an advisor could receive such compensation if there is an intention or actual situation where clients can/will do business with that commission-based entity to begin with.

As a result, the CFP Board needs to recognize that its 3-bucket strategy is really a 2-bucket strategy - either the client pays the advisor, or the client pays an outside party that is related - and the only purpose of the 3rd bucket (which might be better labeled as "Bucket 2b") is to determine if an outside party that received a commission is a related party or not. To view outside relationships in the absence of what the client actually pays simply leads to nonsensical outcomes; scenarios where no client actually pays a commission to anyone in any way at any time, yet the advisor must disclose that he/she is receiving a commission that doesn't exist in the first place!

Fixing this definition - which the CFP Board can do any time, because the 3-bucket strategy is not part of the official Practice Standards, and is merely an internal self-created administrative framework used to interpret (or perhaps now mis-interpret!) those rules - would greatly help to resolve a number of problematic situations the CFP Board is now facing, from advisors who maintain an insurance license (e.g., for advisory purposes) that mean they could earn a commission but have no intention to do so, to advisors whose clients pay only and entirely fees but happen to have an ownership interest in an outside "unrelated" commissionable entity that no clients do business with (from a family insurance business to owning stock in a bank or broker-dealer to having a portion of a large firm owned by a financial services holding company), to advisors who happen to work for a broker-dealer or bank but no clients ever actually pay a commission to anyone. In fact, given the CFP Board's rules, there are also thousands of "commission-only" advisors who are also in violation of the compensation disclosure rules; as I pointed out months ago, it's virtually impossible to find a financial services firm that isn't at least capable of charging a fee, which means any advisor working for such a firm - which would be all advisors! - cannot be commission-only and in fact should be required to disclose that they are commission-and-fee as well! In other words, the CFP Board's problematic rule not only casts a large number of fee-only advisors as "commission and fee" by ignoring what clients actually pay; it also leaves virtually every "commission-only" advisor equally in violation of the rules as well for the same reason!

And again, the common theme to all of these problem situations is that the CFP Board is basing compensation on what "could" happen and the nature of the firms advisors work for, are affiliated with, or simply own as a part of their portfolio, while failing to recognize and remember that the whole purpose of compensation disclosure is to disclose based on what clients actually pay. If no clients ever pay commissions to anyone in the first place, a mere ownership or employment relationship should not "taint" the characterization of the advisor as being "fee only" (any more than working at a firm that could earn a fee should taint an advisor's disclosure of "commission-only" if the truth is that they really are solely compensated from client by commissions!). Instead, a requirement to disclose "commission and fee" should only pertain to situations where the clients actually pay a commission and a fee in the first place, and it can be shown that the commission and fee were each paid to the advisor and/or a related party. At that point, we'll finally have a logical compensation disclosure rule: where advisors must disclose how they're compensated based on what clients actually pay, the determination of a related party is based on whether the advisor receives a direct or indirect non-trivial economic benefit, and advisors are not required to disclose commissions (or fees) that don't actually exist in the first place!

Or more simply, in the context of the CFP Board's fundamental definition of compensation - "any non-trivial economic benefit, whether monetary or non-monetary, that a certificant or related party receives or is entitled to receive for providing professional activities" - perhaps it's time to realize that an advisor can't be "entitled to" receive a form of compensation that no client ever actually pays! After all, just think of it from the client's perspective: are we really helping to bring clarity to consumers - the whole point of compensation disclosure in the first place - by requiring advisors to disclose types of compensation that don't actually exist and their clients won't pay in the first place? Wouldn't it be a clearer and stronger consumer protection to require advisors to disclose how they're actually being compensated by their clients? Why is that so hard for the CFP Board to implement?

Michael, you are doing the industry a significant favor by continuing to address and clarify this compensation issue. The CFP Board has done none of us a favor in their seemingly arbitrary, rules-based approach devoid of common sense. Ultimately, this needs principles, not rules. Those who benefit from commissions paid by clients cannot and should not be fee-only. Specific circumstances will vary, but if the principle applies, then let’s not let our inability to write the rules well get in the way. Thanks for your continued service.

Thanks Norm! I appreciate the feedback!

The CFP Board continues to claim it bona fides with more artificial claims of moral superiority. By promoting the new commission structure called “fee-based planning”, the Board has totally obfuscated distinctions between fees and commissions. . Sadly, many of its newer certificants have convinced themselves that having simply converted their income model to “fee based” they have become superior professionals.

Russ,

The CFP Board is not “promoting the new commission structure called ‘fee-based planning'”. In point of fact, “fee-based planning” is not even a valid compensation disclosure under CFP Board rules in the first place. The choices are fee-only, commission-and-fee, or commission-only. That’s it.

– Michael

A thorough dismantling of the board’s logic, very nice job. What disturbs me the most was the arbitrary fashion in which they pursued mr Goldfarb et al, yet gave a free pass to thousands of wirehouse and NAPFA members clearly violating the rules as they interpret them. Either they rescind those sanctions or they must go after the violators. As evidenced by the Goldfarb case, merely changing your compensation description does not preclude the cfp board from pursuing sanctions. Thus all of those profiles that were unilaterally changed by the board doesn’t shield the violators from having a complaint filed against them. This is a fundamental issue of integrity and fairness at its very core. Leadership must be held accountable for this grave violation of cfp and frankly the publics trust. It’s sad to see it come to this but it is time to seek the resignation of Kevin Keller and Michael Shaw, and Nancy Kistner for allowing this disaster to occur under her watch as chair of the board. What is also disheartening is that no one on the current DEC had the courage to speak out against this lack of integrity and their current chair Martin Siesta should be ashamed.

Michael,

I guess the only part I don’t get is how receiving dividend income from an investment is compensation. Doesn’t compensation have to be in exchange for providing some kind of service?

Steve,

In the extreme, I could claim that I’m “fee only” by just referring all my clients to a commission-based entity that I own, for which I receive all the profits of the business (in the form of dividends) but claim I’m “not paid a commission.” So the basis of the rule is to recognize that compensation a client pays to a related party that the advisor collects in the form of dividends/business profits is still (indirect) compensation of the advisor.

That being said, part of the point here is that the CFP Board has taken this definition too far. It’s one thing to recognize that if an advisor receives profits from a business that the advisor directed clients to, it’s a form of indirect advisor compensation. It’s another to just say “any dividend from an entity that generated commissions can be commission-based income for the advisor” when the reality is that the dividends may “just” be from an investment and not really a form of client compensation. Yet this was exactly the issue in the case of Goldfarb – he owned a 1% interest in a private broker-dealer from which he received a small dividend, and that income was a major factor in why he was deemed to be “commission and fee” even though it was never shown that ANY of his clients EVER actually did business with that entity.

Thus, again, the point of this article – there’s a difference between “profits from a business attributable to clients, which represent indirect compensation” and “profits from a business I just happen to own/invest in.” Yet according to the CFP Board’s rules, there’s no difference. Even a random stock in my portfolio (the financial services companies in my S&P 500 fund) “could” constitute commission income, and the only reason they wouldn’t is at the discretion of the Disciplinary and Ethics Commission to decide they’re not based on “the facts and circumstances” – which is a hopeless standard because no one will know whether they’re in trouble until it’s too late and they’re already disciplined (which, again, was the scenario with Goldfarb).

– Michael

Michael, are you saying I’m fee only if::

I spend an hour trying to talk a client into an annuity that will pay me a nice commission. He or she instead opts for my fee only management service. No commission was paid.

Einstein,

No. Presuming you had the proper licenses and broker-dealer relationship to be compensated by the annuity commission, if you’re holding out products/services to be compensated by commissions, then you must disclose the commissions.

The point is that if you happen to have an annuity license and haven’t sold annuities in years and don’t sell annuities and don’t try to sell annuities and don’t in any way attempt to sell a commissioned product, the fact that you happen to have an insurance license should not be fatal to being fee-only.

– Michael