Executive Summary

With the ever-increasing breadth of information available online with each passing year, consumers have more and more information at their fingertips – accessible with a smartphone or tablet! – and problems that once required paid experts for solutions can now be resolved with a quick Google search.

Yet while the power of internet searches can solve more and more complicated problems, when it comes to the real-world challenges of our financial lives, we hit a wall; some problems are just too complex to be solved with information alone, and still require the guidance of an expert to navigate. Of course, real world financial planning problems can be so complex, the financial planner can’t and won’t likely have all the answers, either. There is too much uncertainty for a known outcome, too many what-if scenarios to consider, and ultimately most people face practical constraints on their resources that require them to choose from the available trade-offs; there are no “right” choices, just paths to consider and consequences to weigh.

Which means in the end, the highest and best purpose of financial planners may not simply be to consult with and answer complicated questions, but to actually work collaboratively with clients utilizing technology to help them simulate the possibilities in real time, choose which goals to pursue, and then leverage the planner’s knowledge and experience to craft a plan to get them there.

The inspiration for today’s blog post is a recent book I have been reading entitled “Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling” by former advisor and entrepreneur Patrick Sullivan and psychologist Dr. David Lazenby. While the title may suggest the book is about “sales”, make no mistake - this is one of the most compelling books you'll read all year that makes you rethink how you deliver financial planning to clients. It provides a fascinating glimpse into the future intersection between technology and the human delivery of financial advice – and an especially prescient one, as the book was written in 2006 but remains as relevant as ever (or even more so!) in today's environment!

The inspiration for today’s blog post is a recent book I have been reading entitled “Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling” by former advisor and entrepreneur Patrick Sullivan and psychologist Dr. David Lazenby. While the title may suggest the book is about “sales”, make no mistake - this is one of the most compelling books you'll read all year that makes you rethink how you deliver financial planning to clients. It provides a fascinating glimpse into the future intersection between technology and the human delivery of financial advice – and an especially prescient one, as the book was written in 2006 but remains as relevant as ever (or even more so!) in today's environment!

Complicated Versus Complex Problems And Financial Planning Simulations

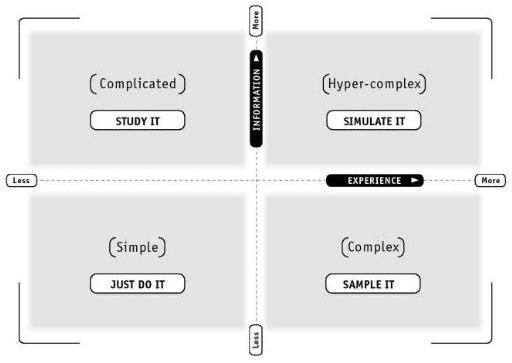

As Sullivan and Lazenby point out, in the world of problems, not all are created equal. Some problem are relatively simple, and often you can “just do it” and figure it out as you go. Other problems are more complicated, and greater information, or some outright expertise is necessary; the problems are solvable, but there may be a lot to learn to solve them correctly. The unique distinction about simple or even complicated problems, though, is that ultimately the solutions can be known or figured out, at least once the requisite information is gathered and knowledge can be applied.

By contrast, some problems are not merely complicated, they’re actually complex. The key variables to the situation are interrelated, and changes to some may alter the others, which introduces a level of unknowable uncertainty to the outcomes that can’t be solved by logic alone, and instead experience begins to drive the decision-making process. For instance, as Sullivan and Lazenby point out, you don’t learn to ride a bicycle by just reading about it, and you (usually) don’t buy a sports car based on statistics alone; in both cases, you have to actually experience them (ride the bicycle, or take the car for a test drive) to get through the process.

In the extreme are “hyper-complex” problems, that require both a high degree of knowledge and experience to effectively solve (or at least navigate). For example, whether it’s heart surgery or flying an airplane, it’s not enough to have some with “just” good book knowledge, or someone with “just” experience but no knowledge of the underlying systems and structures; ultimately, you need someone with both, and a feedback system to know how you’re progressing towards a not-entirely-knowable future.

As Sullivan and Lazenby explain, the reason why it matters to characterize the types of problems we face is that the solutions to those problems vary as well. Simple problems can be solved by just doing it, while complicated problems require study first. Complex problems can be tackled by experimenting and learning from experience. But hyper-complex problems require something more – there’s too much unknown to just study it, and it’s not practical to learn from experience, so instead it’s necessary to simulate outcomes and try to learn by seeing how a wide range of alternative scenarios might play out in order to choose a path amongst them.

Source: Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling by Sullivan & Lazenby

Collaborative Planning To Solve Hyper-Complex Problems

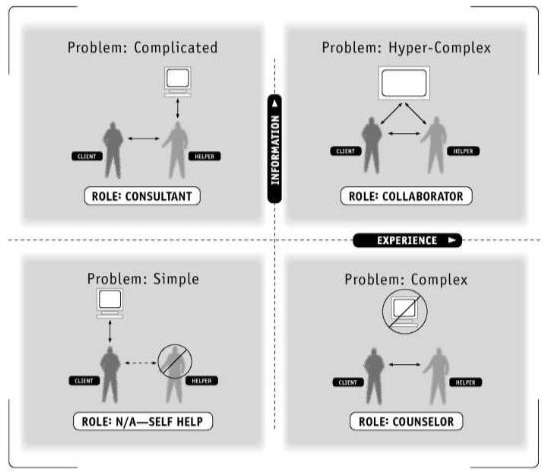

The reason it’s important to understand these distinctions in the types of problems is that the role of other people to help in solving those problems varies by the complexity level:

With simple problems, often no help is needed. Simple problems are essentially “do it yourself” problems (or the kinds of things that can be looked up).

Complicated problems often entail the role of a consultant to find a solution. The answers can be learned, but it may just be easier to hire and pay an expert who’s already studied it, can use tools to do the appropriate analysis, and can identify and explain/provide the solution.

In the case of complex problems, the level of uncertainty means there often is no single right answer to know and deliver. Analytical tools are often put aside, and the role of the helper is more like a counselor; someone to help you think through the situation and help yourself.

With hyper-complex problems, though, even just a counselor isn’t enough, because the challenges are so complex that it’s not enough to just think them through, and it’s not always feasible to just try them out due to a lack of knowledge. Instead, the role of the helper is to be a collaborator, to use tools to help simulate the problem together and analyze and think through the prospective scenarios and their potential outcomes.

Source: Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling by Sullivan & Lazenby

An important key here is that hyper-complex problems cannot be solved by technology tools alone; there may be too much information to model, too much uncertainty for concrete outcomes, and technology lacks the experience and “street smarts” to be properly applied to individual human circumstances. In an environment where some advisors feel threatened by the “rise of the robo-advisor” and more simply the danger that internet search and web-based tools could make them irrelevant, technology may help solve simple and complicated problems, but the hyper-complex remains in the unique domain of requiring (expert) human assistance as well and may represent the last bastion in the world of advice that technology cannot replace.

On the other hand, it’s notable that trying to solve hyper-complex problems with “just” a consultative approach doesn’t work either. When problems are “merely” complicated, but can be solved with sufficient knowledge, information, and analysis, it’s possible to gather data, analyze it, come up with a solution, and provide a recommendation (the typical financial planning process!). However, with hyper-complex problems a “take the information, analyze it, and come up with the solution” approach can actually be remarkably ineffective. Instead, a more engaging and collaborative approach is necessary.

Banishing The “Wizard Of Oz Effect” And Real-Time Collaborative Planning

According to the CFP Board Practice Standards, the 6-step financial planning process entails Establishing the client relationship, Gathering data, Analyzing the data, Developing recommendations, Implementing recommendations, and then Monitoring. In practice, this typically means having 1-2 meetings with the client to establish the relationship and gather data, followed by a break in time when the advisor analyzes the data and develops recommendations (inputs information into the software, evaluates the results, and produces “the plan”), before ultimately scheduling another meeting with the client to deliver the recommendations for implementation. Or as Sullivan and Lazenby put it, the advisor gathers the information with the client, and then disappears like the Wizard of Oz behind the curtain (to number-crunch with their computer!), before grandly re-emerging to provide their advice.

The problem with this “Wizard of Oz Effect” is that it removes the client from the process at what is actually one of the most crucial points. Were the problem merely complicated, the planner could indeed take the information, analyze it, and like a good “consultant” deliver the recommendations. But when the problem is more complex – like real-world financial planning situations – it’s not enough to just study the numbers and provide a recommendation, because of the natural trade-offs entailed in real-world financial planning situations. Deciding to save more for the kids’ college funds means pushing retirement later. Trying to avoid delaying retirement means saving more now. Saving more now means changing spending plans. Giving up on spending requires a commitment that is hard to justify unless the client has buy-in to the plan. And it’s hard to have buy-in to the plan when the client wasn’t a part of crafting it in the first place, because the advisor did it on the other side of the curtain.

The traditional approach to solving this challenge is to try to anticipate the different types of “what-if” scenarios the client might want to view… an approach which occasionally works, but often just leaves clients asking for additional versions of the plan, planners who are frustrated by the number of iterations that clients keep asking them to run, and ultimately ends with clients who once again don’t have real buy-in to the solution by the time the advisor comes back with the 7th version of the plan (or worse, the advisor refuses to keep running different versions of the plan and the client is cut off before being able to arrive at a decision at all).

As an alternative to solve this problem, Sullivan and Lazenby advocate a collaborative planning approach, where the advisor does not disappear behind the Wizard-of-Oz curtain to do the number-crunching analysis, but instead uses the software live, interactively, on the spot, with the client – a feat that is actually quite feasible in today’s age of high-powered computers and relatively inexpensive 60” television/monitors. After all, think of a typical situation where a client asks for a plan, and then starts asking “What if I retire at 64 instead of 62?” “What if I save another $500/month instead?” “What if I retire at 64 and save another $500/month?” “What if…” Instead of going back to the computer with each scenario to analyze the situation, re-run the reports, and bring back to the client to discuss, it was simply there on a big-screen monitor to make adjustments on the fly and discuss the implications and trade-offs of each decision?

Notably, for much of its history financial planning software tools weren’t even capable of such on-the-fly planning – and in point of fact, Sullivan and Lazenby wrote their book in 2006(!) and at the time had such difficulty finding software tools, their made their own visual interactive financial planning software Scenario Now to allow for a more interactive and collaborative financial planning process. But increasingly, financial planning software tools are evolving to provide such capabilities, from easier data gathering input workflows to a better user interface to an outside series of sliders to allow the planner and client to engage.

But at the most basic level, just imagine for a moment that the next time a client wants to look at lots of different “what if” scenarios for their plan, you simply loaded it up on the big screen, handed the keyboard and mouse to the client, let them grab the sliders, and explore the possibilities of their plan on the spot, while you as the financial advisor guided them through the process and used your experience and wisdom to help them interpret the results they were seeing and formulate a game plan.

Welcome to the world of real-time collaborative financial planning.

I love the idea of an interactive, flowing environment.

OK — what are 2-3 solutions that are currently available to planners?

Stevie,

The folks who did the Scenario Selling book built their own software called “RetireNow”, which you can see at http://www.scenarionow.com/

For our more “traditional” financial planning software tools that have some collaboration capabilities, MoneyGuidePro has built something to do this, FinanceLogix has done it. I believe eMoneyAdvisor is working on something to enable this. I’m not certain if NaviPlan has capabilities to do it, and I don’t believe MoneyTree does either at this point (beyond just going back into the full planning software, changing inputs, and then going back to view results, but that’s not very conducive to a real interactive client experience).

– Michael

emoney has this tool already, via their Decision Center released less than a year ago.

Awesome, thanks for clarifying. Hadn’t seen the eMoney Decision Center yet, but will try to check it out soon! 🙂

– Michael

Decision Center is still quite limited (e.g. it only runs the base facts scenario and is only open to the licensed “advisor” not the planner). But it could soon be very helpful.

I encourage you to explore the updates to Emoney, which rolled out over the weekend. Decision center was updated along with better Social Security analysis and many more updates. One final addition worth noting is a goal what if section. It looks very similar to MoneyGuide Pro in this area. Overall, with this update, Emoney continues to prove they are the software leader.

Stevie,

One quick follow-up to this – I’m told that MoneyTree’s “Silver” package also has some good “What If” capabilities to help clients look at multiple scenarios.

And the client should be convinced that such collaborative decision making will occur in the future. It has always been my view that the greatest value add for an advisor is creating an effective decision making environment and making it (and us) available to the client. That is the essential value of a retainer.

Great piece Michael – thanks for sharing the book…

Thanks Jim. I think you’ll really enjoy the book! 🙂

– Michael

Hi Michael – great post, we find that very encouraging since it’s exactly what we are working on at financial.me.

Having a collaborative environment makes so much sense. Visibility between the clients monies/assets and the advisor provides a very powerful tool, where traditionally the relationship has been very reactive.

Financial.me, whilst still in beta, has many of the features and functionalities you mention. Specifically, our forecast graph breathes new life into the staid old a numerical retirement planner. It runs a Monte Carlo simulation in realtime in the browser, and forecasts out a range of possible future states, represented as visual bands. Users (hopefully with their advisor!) can enter future life events (like retirement) and immediately see the effect – even dragging them left or right to see what would happen if they retired earlier or later.

We’re not finished with it yet, but for anyone interested in Michael’s article, we would love your feedback on the forecast planner.

Martin

Michael, Lance Roberts and I discussed your post this morning. I believe, like you seem to, that collaborative financial planning, where applied knowledge and technology, allows us as planners to better help clients migrate through complex issues towards “best” solutions. This is a far better solution than winging it on a yellow pad or grease board. I have used the touch screen TV’s in our conference room to do what if’s on the fly with clients to help illustrate the solutions…and it can be very effective and allow the client to feel more part of the process.

Also, it is yet another example of why a single questionnaire based “robo” won’t work in complex solutions and may allow the quick response of a robo website to guide a client down the wrong path. It goes back to “applied knowledge” that can only happen in an interactive experience vs. a 5 question robo-based solution. Don’t get me wrong, robo-advisors will have their place, but maybe not in complex situations. I believe it is similar to the issue where we still need primary care physicians even when we have WebMD.

I feel good about myself that someone else came to the same conclusion that I did. When I was actively doing planning for individual client’s, I came to the conclusion that everything was better if we sat on the same side of the table and engaged with the plan itself instead of sitting on opposite sides of the table and engaged with each other.

I switched to doing every plan live, in real time either in my office or over the computer. I actually came to prefer the computer/phone presentation because it allowed us to only focus on the plan. It also solved the problem of organizing both spouse’s schedules. I could be in my office, husband could be in his office, and wife could be in her office. Everything worked better for all of us.

FedEx is cheap compared to dealing with clients being on the road to my office or me being on the road to them.

Most importantly, by pulling the curtain back from the “financial planning expert” we could deal with multiple scenarios and tackle the complex issues.

I am looking for software that can do interactive quick assessments on the fly for clients to show them value at very little cost in term of my time. Then if they want to dig deeper with a more detailed plan I can do that as well with the same software. One the detailed side I would need it to be able to handle sophisticated estate planning techniques as well as Social Security scenarios. Does anyone know for certain this is available somewhere. Of yes. It needs to integrate with my custodians as well. If anyone knows of this please let me know.

I share the interest of Tim Schaefer looking for interactive quick assessment software. I was at my best with Quicken Financial Planner ($19.95) in the late ’90s. Clients and I sat side by side and played “This is Your Life” as we filling in the variables. When the conclusion was a shortfall, the client started to think what needed to happen. No big pleather binder, no ream of paper…each year we visited it again…Are you on track, ahead or behind and…why? Market activity, savings, spending? I would pay 10 times for that little program and a computer that can run it. What’s out there?

Reading this review, I recalled the old saying attributed to Albert Einstein, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” We must be careful; oversimplification can push the complex into chaos. Even after 30+ years as a financial planner, I still occasionally need to be reminded that “I don’t know what I don’t know.” I look forward to reading the book.

I recently saw a demonstration of Advizr financial planning software. Advizr allows advisor and client to work together developing the financial plan, including the ability to adjust client input data and show how different scenarios affect the client’s financial planning goals. The real world of real-time collaborative financial planning may be just around the corner.

Enjoyed your blog and will order the book.

Interesting! A lot to think about, so thank you for sharing!

Financial planning is so critical to the growth and success of any business. Great post and thank you for sharing!