Executive Summary

On July 18th of 2018, the New York Department of Financial Services (NY DFS) issued a new Best Interest Rule (Regulation 187) that (re)defines the meaning of “clients’ best interests” for life insurance product recommendations effective February 2020, including the due diligence obligations that apply to life insurance recommendations. Previously, due diligence for life insurance product recommendations was governed by the National Association of Insurance Commissions (NAIC) Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation #582 (as adopted by each State).

And perhaps surprisingly, NY DFS Regulation 187 prohibits such life insurance policy illustration comparisons as due diligence for product recommendation (despite attorneys for the life insurance industry lobbying to “expressly include” illustration comparisons, which NY DFS rejected). The Rule's omission of illustrations comparisons is also consistent with guidance from other financial, insurance, and banking industry authorities warning against illustration comparisons as “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable. Instead, NY DFS Regulation 187 requires product recommendations be based on a careful, skilled, prudent, and diligent evaluation of costs, performance, and risks relative to benefits.

In this guest post, Barry Flagg, an insurance expert and founder of Veralytic (which publishes pricing and performance research on life insurance policies), explores the details of the new NY DFS Regulation 187, the fundamental problems with life insurance policy illustrations (especially when used for comparison purposes), what Regulation 187 will require for life insurance due diligence in the future, and how fiduciary advisors must adjust when doing their own due diligence on behalf of clients.

The key issue, though, is simply that because of the number of “moving parts” that underlie life insurance policy illustrations for cash value life insurance, it’s not enough to merely look at which policy is projected to have more cash value, or requiring less in premiums, in the long run. Because underlying those projections are assumptions about returns (which may not be realistic relative to the company’s actual general account investments or historical results), along with assumptions about costs (which may not be guaranteed nor even stable and consistent with the company’s historical costs). And in fact, because life insurance policy illustrations have historically been used as a point of comparison, insurance companies have had unhealthy incentives to ‘game’ their policy illustrations to project cash value more favorably… without necessarily acknowledging the underlying risk of what may be very tenuous assumptions.

More broadly, the NY Best Interest Rule is also significant given the broad efforts to more clearly define clients’ best interests (e.g., the DOL Rule and the SEC Best Interest Rule), and given NY DFS “reputation as a first mover on important insurance regulation matters”, there is now an increased likelihood of additional state-level fiduciary regulation on life insurance, matching the recent trend of state fiduciary rules on investment advice and recommendations as well. And given the predominant use of illustration comparisons as supposed due diligence, the questionable use of illustration comparisons for product recommendations, the growing legislative and regulatory activity around re‑defining clients’ best interests for product recommendations, and NY DFS’s standing as first-mover on important insurance regulation, the NY Best Interest Rule for life insurance raises significant ethical and practice management considerations for CFP professionals and other fiduciaries advisors – both in and outside New York - about how advisors should do basic due diligence to determine whether one proposed life insurance policy is really better or worse than another.

On July 18th 2018, the New York State Department of Financial Services (NY DFS) issued a Best Interest Rule for life insurance (Regulation 187). This new Rule re-defines the meaning of “clients’ best interests” for product recommendations to be more consistent with other fiduciary rules, requiring life insurance producers to "act in the best interests of the consumer … based on an evaluation of relevant suitability information … and the care, skill, prudence, and diligence [of] a prudent person … considering only the interests of the consumer in making recommendations." Previously, due diligence for life insurance product recommendations was governed by the National Association of Insurance Commissions (NAIC) Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation #582… creating a significant gap between the existing rules and expectations for advisors evaluating and comparing life insurance policies in the past, and what will be required of them going forward (both inside and outside New York).

Product Recommendations under NY DFS Best Interest Rule for Life Insurance

The NY DFS Best Interest Rule defines clients’ best interest in terms of a) costs that can be justified, (i.e., cost of insurance charges, mortality and expense fees, investment advisory fees, surrender charges, charges for riders, etc.), b) performance that is reasonable to expect (i.e., availability of cash value, equity-index features, limitations on interest returns, etc.), and risk that is appropriate for the circumstances (i.e., market risk, guaranteed interest rates, etc.) “based upon all products, services, and transactions available to the producer.”

Defining clients’ best interests for life insurance product recommendations in terms of costs, performance, and risk is well-established by centuries of debate, legislation, litigation, and case law. However, the life insurance industry argues that additional “regulation is unnecessary because … comprehensive state laws and regulations … [already] assure that life insurance products are sold consistent with the best interest of consumers." But this position seems uninformed, out-of-step with related authority, and replete with loopholes.

For instance, the NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation was promulgated in 1995 with stated goals to “ensure that illustrations do not mislead purchasers of insurance and to make illustrations more understandable.” However, in Actuarial Guideline XLIX (AG49), the NAIC concluded in 2015 that the Illustration Model Regulation failed to achieve those goals by instead producing a “lack of uniform practice … [resulting in] illustrations that use [apparently] the same index and crediting method [but] often illustrated different credited rates.”

In addition, NAIC Illustrations Model Regulations don’t require disclosure of costs, performance, or risk. As such, the prevailing practice of comparing illustrations as a means of due diligence for product recommendations doesn’t even consider the very elements essential to well‑established definitions of clients’ best interest. To the contrary, NAIC‑compliant illustration comparisons are now considered “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable by financial, insurance, and banking industry authorities.

For instance, FINRA issued IM-2210-2(c) stating that “[i]t is inappropriate to compare a … life insurance policy with another product based on hypothetical performance…” because “[a]ny comparison… must disclose all material differences…including investment objectives, costs and expenses, liquidity, safety, guarantees or insurance, fluctuation of principal or return [i.e., risk], …[the] omission [of which] … would cause the communications to be misleading” according to Rule 2210(d).

Similarly, the OCC’s Handbook for Unique and Hard-to-Value Assets cautions that a “policy illustration is subject to a high degree of fluctuation” and therefore not reliable for determining which product(s) are in the client’s best interest. Even the Society of Actuaries concluded in their FINAL REPORT OF THE TASK FORCE FOR RESEARCH ON LIFE INSURANCE SALES ILLUSTRATIONS that, “Illustrations should not be used for comparative policy performance purposes” because doing so “is fundamentally inappropriate.”

NY DFS Regulation 187 also requires that product recommendations “reflects the care, skill, prudence, and diligence that a prudent person acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use under the circumstances then prevailing.” The duty to exercise reasonable care, skill, and caution is also well-established as an essential element of product recommendations in the clients’ best interests, but also absent from NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation.

Given the predominant use of illustration comparisons as supposed due diligence, the questionable use of illustration comparisons for product recommendations discussed in the next section, the growing legislative and regulatory activity around re‑defining clients’ best interests for life insurance product recommendations, and NY DFS’s standing as a “bellwether” for important insurance regulation, the NY Best Interest Rule for life insurance poses significant ethical and practice management considerations for CFP professionals and other fiduciary advisors both in and outside New York.

Product Recommendations under NAIC Illustration Model Regulation

NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation was intended to “ensure that illustrations do not mislead purchasers of insurance and to make illustrations more understandable.” With such a goal, it’s certainly plausible that supposed “apples-to-apples” illustration comparisons would be used as due diligence for product recommendations. However, the NAIC since concluded that illustration comparisons “lack of uniform practice … [result in] illustrations that use [apparently] the same index and crediting method [but] often illustrated different credited rates.”

Let’s, therefore, examine below why illustrations comparisons are considered “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable by financial, insurance, and banking industry authorities, and in turn can create an ethical dilemma for CFP professionals and other fiduciary advisors with a duty to exercise reasonable care, skill, and caution.

Consider a 45-year-old extra-healthy client needing $1,000,000 of permanent life insurance and wanting cash value as an exit strategy in case he no longer needs this coverage. The CFP professional or other fiduciary advisor calls their trusted broker, BGA, or IMO for premium quotes payable for 20 years and calculated using a 5.0% interest rate so quotes can be compared “apples-to-apples” to determine which product is best for this client.

The broker, BGA, or IMO then sends over a comparison of illustrations for two different products – a traditional universal life (UL) product and an indexed universal life (IUL) product – from two well-known insurers that are both highly-rated for financial strength and claims-paying ability. Both illustrations prominently display the requested 5.0% assumed rate of return in column headers immediately above the hypothetical values that were (supposedly) calculated using that rate of return.

The premium for the UL product is ~$8,500. The premium for the IUL product is ~$13,000. No competition, right? This (supposedly) “apples-to-apples” premium comparison clearly indicates the UL product offers lower costs to this client in this situation, right? After all, the premium for any product will always be equal the difference between sum of all cost of insurance charges (COIs) and expenses (E), less the sum of interest earned (i%) and used to pay internal costs (i.e., premiums = COIs + E – i%). So if the interest rate used to calculate hypothetical premiums is the same, then the difference in premiums must be attributable to the difference in costs, right?

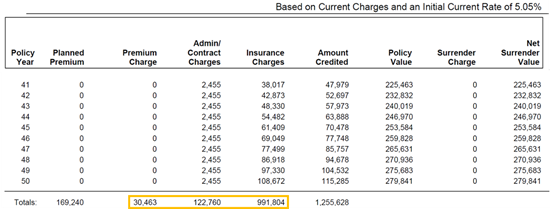

Let’s take a closer look at excerpts from the actual insurance-company-produced illustrations for both products showing actual costs the insurer represents they will charge, as well as the interest presumably calculated at the requested 5.0% assumed interest rate. As you can see in Figure 1, the UL product charges $30,463 in premium loads, $122,760 in fixed administration expenses (FAEs), and $991,804 for cost of insurance (COI) charges, totaling of $1,145,027 through policy year 50.

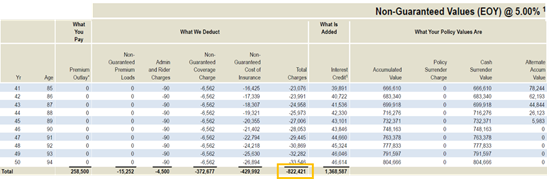

On the other hand, the insurer of the IUL product represents they will charge a total of $822,421 comprised of $15,252 in premium loads, $377,177 in fixed administration charges (FAEs), and $429,992 in cost of insurance charges (COIs) also through policy year 50 (i.e., age 94 as an example life expectancy of an extra healthy, high-net-worth client), as shown below in Figure 2.

But how can the premium for the UL product (i.e., ~$8,500 a year for 20 years) be 35% LESS than the premium for the IUL product (i.e., ~$13,000 a year for 20 years) when the costs in the UL product are nearly 40% MORE than the IUL product? It is mathematically impossible for a premium calculated using the same assumed rate of return to be lower when policy expenses are greater unless the amount of assumed interest credited is not as it appears.

So let’s look more closely at the interest component. Interest actually credited to a policy in any given year will be calculated starting with the end-of-prior-year policy account value, adding new premium contributions, deducting cost of insurance charges (COIs) and policy expenses, and then multiplying that result by the applicable interest rate. For instance, the interest credited on an account of $110,000, plus $0 in premiums, less $9,000 in COIs and expenses, would be a little more than $5,000.

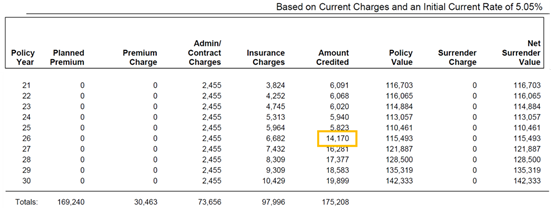

However, the amount shown to be calculated and credited in these UL and IUL products is different than the above math suggests. As shown in Figure 3, the account value of the UL policy is projected to be $110,461 at the end of policy year 25, plus premium contributions of $0, less $9,137 in total policy costs deducted (i.e., $0 in premium loads, $2,455 in FAEs, and $6,682 in COIs) equals $101,324. However, the amount of interest shown to be credited is $14,170, which is NOT 5.0% and instead closer to 14.0%.

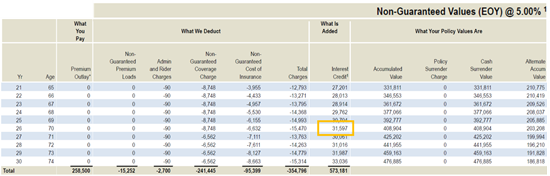

Similarly, Figure 4 shows the account value of the IUL policy is projected to be $392,777 at the end of policy year 25, plus premium contributions of $0, less $15,470 in total policy costs deducted equals $377,307. Once again, interest of $31,597 shown to be credited on $377,307 is clearly NOT 5.0%, and instead closer to 8.0%. While the degree of exaggeration of interest earnings is less than in the UL product, both illustrations are clearly NOT “apples-to-apples,” and instead downright misleading. Simply put, both policies were “illustrating” 5% returns, yet in practice, both are assuming materially-higher-than-5% returns.

To be clear, this is not to say that either of these insurers cannot actually credit more than 5.0% by providing investors additional returns above-and-beyond the originally projected rate. For instance, some insurers claim to be able to credit higher interest due to investment strategies that include greater exposure alternative asset classes, but illustrations don’t consider the greater risk inherent in such asset classes. Other insurers claim to expect cost savings under certain circumstances that they project (but don’t guarantee) to pass back to the policyholder in the form of interest credits. Others still inflate the amount of hypothetical interest illustrated by charging additional costs to purchase additional options on an equity index (e.g., S&P 500) that are presumed to result in additional policy earnings, but without reflecting the additional risk that some of the additional options will expire “out-of-the-money” resulting in a loss instead of a gain on the additional options.

In other words, the above is not intended to dispute any insurer’s at-least-potential ability to earn and credit more interest but is instead intended to demonstrate that comparing hypothetical premiums, cash values, and death benefits does not necessarily identify the product with the lower costs, nor even reflect the same return assumptions when the same return assumptions are inputted in the first place, as has been commonly promoted by IMOs, BGAs, and even fee-only consultants. As such, hypothetical illustration comparisons are useless as due diligence for product recommendations and determining which product is better (or not), and relying on them can expose CFP professionals, financial advisors, other fiduciary advisors, and especially ILIT trustees, to risk of breach of duty to exercise reasonable care, skill, and caution for reliance on “decision support” that’s now considered “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable by financial, insurance, and banking industry authorities.

The above is also far from an isolated example of “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable illustration comparisons. As many as 70% of all IUL products plus some UL products calculate hypothetical policy values using un(der)-disclosed inflated interest assumptions. And because such inflated interest assumptions are un(der)-disclosed, it’s at least difficult for most advisors and almost certainly impossible for most clients to discern the illustrations that include inflated interest assumptions from those that do not, and adjust for the risk of whether those higher returns are really likely to occur or not. With so many advisors and clients relying on illustration comparisons for product selection decision-support, and with so many IUL products illustrating inflated interest assumptions above their stated illustration rate, it’s no wonder IUL products are the top-selling “flavor-of-the-day” product type according to LIMRA.

The Troubled History Of Life Insurance Policy Illustrations

Notably, this is also not the first time that illustrations with inflated interest assumptions have been used in illustration comparisons to sell a particular product type. The practice of comparing illustrations for product recommendations effectively started in the 1980s when illustrations of UL products calculated hypothetical policy values, using then-double-digit interest crediting rates, and were compared to illustrations of WL products that calculated hypothetical policy values using much lower dividend interest crediting rates… even though invested assets underlying the cash values of both are required by regulation as a practical matter to be invested predominantly in the same asset classes.

As we saw above, when an insurance illustration calculates hypothetical policy values using a higher assumed rate, and is then compared to another illustration that calculates hypothetical policy values using a lower assumed rate, the illustration using the higher assumed rate can appear to be a “better” product when in fact, the costs in the supposedly “better” product are actually higher. The rational(ization) back then was that UL products would actually credit higher rates because UL products introduced in the high-interest-rate environment of the early 1980s and could invest in new higher interest-bearing securities without the drag of an existing portfolio of lower interest-bearing securities.

However, life insurance products by their very nature are long-term financial instruments. As such, if prevailing interest rates remained high, then the yield on interest-bearing securities underlying WL policies would have migrated up as bonds and mortgages matured and were re-invested in higher interest rate instruments. On the other hand, if prevailing interest rates decline, then yields on interest-bearing securities underlying UL policies would migrate down as bonds and mortgages matured and were re-invested in lower interest rate instruments. In fact, prevailing interest rates did steadily decline since the 1980s, and the reverse is now the case where WL dividend interest crediting rates are higher than UL interest crediting rates (at least for the time being, potentially shifting again if and when the direction of interest rates shifts again).

Nonetheless, this practice of comparing hypothetical illustrations as due diligence for product recommendations began innocently enough. The 1980s brought a variety of new and different products, and illustrations were the only source of information for trying to understand costs, features, and benefits. However, comparing hypothetical policy values for UL versus WL products calculated using dramatically different assumed crediting rates even though both products are required by regulation to invest assets underlying cash values in the same asset classes is just nonsense, and now the subject of critical articles in the financial press (e.g., Universal Life Insurance, a 1980s Sensation, Has Backfired).

The use of questionable illustrations comparisons continued in the 1990 when Variable Life (VL) illustrations were compared to UL and WL illustrations, even though VL hypothetical values were calculated using assumed earnings rates that were again 100s of bps higher than the illustrations for UL and WL products, and without any consideration of the inherent volatility of equity returns and the corresponding impact on hypothetical policy values.

Ironically, the insurers of the products shown in the earlier illustration excerpts had resisted misleading illustration practices for years but were at a competitive disadvantage to those insurers less inclined to follow the spirit of NAIC regulations. In such an environment – where prudence is punished and recklessness is rewarded – even otherwise responsible insurers have too many incentives to eventually “game the rules” under NAIC Illustrations Model Regulation to better compete in the illustration comparison “beauty contest.”

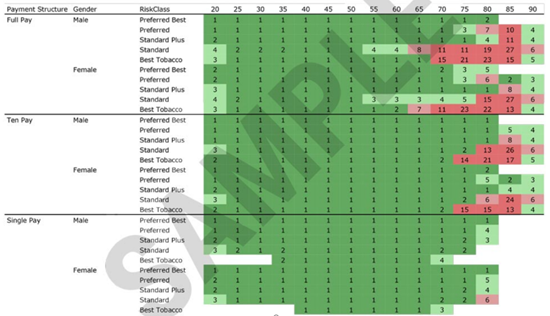

In fact, comparing hypothetical illustrations has become so common that insurance marketing organizations (IMOs), brokerage general agencies (BGAs), producer groups, individual agents/brokers, and/or fee-for-service consultants have created or use computer software to graphically present comparisons of hypothetical policy values, a sample of which is shown below, ranking of “[hypothetical] premiums, [hypothetical] distribution amounts, [hypothetical] cash surrender values, … [hypothetical] internal rates of return, … that help you fully understand the competitive positioning of [the hypothetical illustrations of] products for 30+ life insurance companies.”

Source: LifeTrends

As we already know, the product with the lowest hypothetical premium or highest hypothetical cash value or death benefit may or may not be the product offering the lowest cost. In fact, to the contrary, the product shown above that is overwhelmingly ranked #1 is the same product that actually charges significantly higher costs as shown earlier!

While such computerized systems and graphical presentations certainly seem professional, these charts and graphs are too often still simply portraying the same “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable comparison of hypothetical values as discussed above and only for some limited number of products. In computer science parlance, this is GIGO (i.e., garbage in, garbage out) where flawed or nonsensical input data produce nonsensical output and flawed conclusions.

As such, while the NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation was well-meaning, the practice of comparing hypothetical illustrations as due diligence for product recommendations is proving to be “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable. Most other segments of the financial services industry have evolved beyond using hypothetical product comparisons as due diligence for product recommendations. NY DFS Regulation 187 is an indication that the life insurance industry may also be evolving past using hypothetical illustration comparisons as due diligence for product recommendations, and instead provides a checklist for diligence alternatives to illustration comparisons discussed further in the next section.

Asking For “Detailed Expense Pages” For Life Insurance Due Diligence Beyond Policy Illustrations

At a minimum, whenever presented with illustrations of hypothetical premiums, hypothetical cash values, and hypothetical death benefits as supposed decision support for some product recommendation, be sure to insist that all illustrations include those pages (as shown in Figures 1 through 4). These pages are commonly referred to as “policy accounting pages” or “detailed expense pages” and show year-by-year disclosure of cost of insurance charges (COIs), policy expenses, and the interest/earnings underlying hypothetical premiums, cash values, and death benefits.

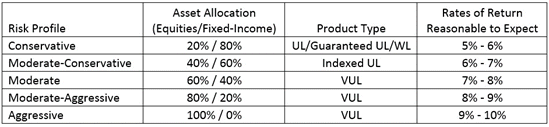

As discussed earlier, without these “policy accounting pages,” there is no way to know whether the costs in a recommended product are competitive or excessive, nor whether interest/earnings required for a policy to work as expected are consistent with actual historical performance of invested assets underlying policy cash values, nor whether the risk corresponding to that interest/earnings assumption is consistent with the clients risk profile. But with these “detailed expense pages,” actual costs can at least be compared among the products being recommended, and interest/earnings can be evaluated for reasonableness relative to asset class benchmarks, and the risk of not achieving interest/earnings assumptions can be gauged against historical performance for various asset allocations.

Illustrations for all universal-life-type products include this year-by-year detail – hypothetical policy values cannot be calculated without them – although illustrations for some old universal-life-type products from insurers no longer actively distributing life insurance products are not able to actually include this detail in certain in-force illustrations.

On the other hand, whole life products, by their design, only illustrate based on the net result of guaranteed factors (rather than separately showing returns and costs so each can be evaluated separately), and hypothetical values over and above the guarantee amounts are similarly reported only net of "excess" refunded charges and "excess" interest (without unbundling either). Therefore, there is no year-by-year disclosure of (unbundled) costs and performance with whole life policies. Which means, for whole life products, advisors must insist on disclosure of the dividend interest crediting rate used to calculate hypothetical policy cash values… so you can at least know if the interest/earnings rate required for a policy to work as expected is consistent with actual historical performance of invested assets underlying policy cash values and/or asset class benchmarks. In addition, with this dividend interest crediting rate, costs can then be approximated using basic algebra (i.e., since hypothetical cash values = premiums – costs + interest, when cash values, premiums, and interest are known, then costs = hypothetical cash values – premiums – interest).

Ideally, though, the fiduciary advisor will go beyond just knowing costs, performance expectations, and risk factors in a particular product, and also measure costs, performance, and risk against the universe of peer-group alternatives. Which is literally the essence of doing a due diligence product comparison in the first place.

Ethical & Practice Management Implications for CFP Professionals & Other Fiduciary Advisors

The NY DFS Best Interest Rule for life insurance prohibits hypothetical illustration comparisons as due diligence for product recommendation. Instead, it requires product recommendations be based on a careful, skilled, prudent, and diligent evaluation of costs, performance, and risks relative to benefits and applies to any transaction with almost any connection to the State of New York. For instance, this NY DFS Rule could/would apply to current residents of New York even if they spend considerable time in another State and may have advisory relationships in another State, as well as to former residents of New York with a life insurance trust created in New York, or with a trustee domiciled in New York, or with financial advisors in New York.

In addition, NY DFS Regulation 187 offers guidance to CFP professionals, financial advisors, other fiduciary advisors, and especially ILIT trustees both in and outside New York, for applying well-established practices for determining clients’ best interests to life insurance. For instance, illustration comparisons that obfuscate costs, performance, and risk, and provide consumers with “misleading”, “fundamentally inappropriate”, and unreliable product information can hardly be defended as being in the clients’ best interests. As such, financial planners and fiduciary advisors that seek out life insurance professionals who have evolved beyond illustration comparison to comply with the NY Best Interest Rule for life insurance should/would enjoy the protection provided by well-established practices for serving clients’ best interests.

Altogether, NY DFS Regulation 187 provides a “checklist” for careful, skilled, prudent, and diligent evaluation of costs, performance, and risks relative to benefits. Given the predominant use of illustration comparisons as supposed due diligence, the questionable use of illustration comparisons for product recommendations, the growing legislative and regulatory activity around redefining clients’ best interests for product recommendations, and NY DFS’s standing as first-mover on important insurance regulation, the NY Best Interest Rule for life insurance raises significant ethical and practice management considerations for CFP professionals and other fiduciary advisors both in and outside New York.

Excellent article. Many CFP and other fiduciary advisors consistently compare cash values just taken from the statements and illustrations. Financial planning software has also made this problem worse because they just ask you to input a number for cash value but that is almost meaningless. I would not be so hard on the CFP’s. Many also beginning insurance professionals also continue to show/believe that higher cash value means their product is better. I wonder who trains them this belief.

Excellent post! TY

Kay

Is it unreasonable for insurance carriers to clearly summarize the assumptions made in illustrations, and (preferably) allow their illustration software to adjust assumptions? It would allow for much more accurate comparisons if the financial planner or insurance agent could match up competing products. Allow the adviser and/or consumer to assess the features and benefits, and the costs associated with those benefits, to determine the best product for their needs.

When I started out in the industry and sold life insurance, I spent hours illustrating policy differences to try and better understand what effect those changes had on price and performance.

I think you’d see the RIA community more fully embrace cash value life insurance if they could better understand the workings of the chassis.

The LI company I work for doesn’t enforce the. Part of Rule 186 that states an illustration must be signed and dated contemporaneously with or before the application, and must be submitted along with the application. Consider this:

App and all other docs, except illustration, e-signed and submitted on 10/17. No illustration in the packet. Agent then submits a wet-signed illustration on 10/21 which is dated 10/13. Very obviously not signed contemporaneously – and there is no way to prove who actually wet-signed the illustration.

When brought to the company’s attention and explaining that the illustration was NIT SUBMITTED with the app, I was told that the company “likes to give agents a chance in case they “forgot” to send in the illustration”. This makes me very nervous.

Is this a good/legal/compliant practice??