Executive Summary

After years of debate over the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, and a nascent movement of states adopting their own fiduciary standards, the SEC has finally issued the first proposal of its long-awaited “Advice Rule” to reform the standard of conduct for broker-dealers, after being authorized under Section 913 of Dodd-Frank nearly 8 years ago to harmonize the regulation of brokers and investment advisers with a uniform standard.

As it turns out, though, the SEC’s proposal is not actually a uniform standard that would require brokers to be fiduciaries, but instead would only partially lift the conduct standards for broker-dealers, with a new “Regulation Best Interest” requirement that would obligate brokers to act in the best interests of their customers when making an investment recommendation… but only at the time they actually make the recommendation. And not at all if the broker is implementing recommendations that were crafted while wearing his/her investment adviser “hat” under a dual-registered B/D-RIA firm.

To help further clarify the nature of the relationship between customers and their brokers, and investment advisers and their clients, given that the SEC is not harmonizing fiduciary regulation for investment advisers and brokers, the regulator also proposed establishing a new Disclosure Form CRS – short for customer/client relationship summary – which would provide a “simple, plain language” 4-page explanation of the consumer’s relationship with the broker or adviser, albeit with wording that will likely be hotly debated in the coming year.

In addition, the SEC’s Advice Rule would formalize an RIA fiduciary’s expectations under the Duty of Care and the Duty of Loyalty, proposes several new potential requirements for RIAs where their standards are actually lower than broker-dealers (in particular, for investment adviser representatives to have a Continuing Education obligation, and for RIAs to potentially have basic Net Capital requirements to ensure they can make good to clients in the event the firm must be liquidated and unwound), and raises the question of whether it’s finally time for “title reform” by proposing that brokers would no longer be permitted to use any title with the word “advisor” or “adviser” (though dual-registered brokers would still be permitted to do so given the RIA “adviser” hat).

Ultimately, the good news of the SEC’s Advice Rule proposal is that it does aim to at least partially lift the standards for brokers, with an aim to further clarify the nature of the broker’s relationship with the customer (and how it differs from an advisor’s relationship with its clients). Yet at the same time, introducing a “Regulation Best Interest” may be so on-the-nose that consumers will actually just be more confused about the difference between a “Best Interests” standard for brokers and a “fiduciary” standard for RIAs… which the SEC defines as the RIA being obligated to act in the Best Interests of its clients, too. And by exempting dual-registered brokers from both the obligations of title reform, and Regulation Best Interest itself, it’s not entirely clear if the SEC is really aiming to clarify the differences between brokers and investment advisers… or to simply induce all broker-dealers to launch corporate RIAs as a safe harbor for their advice-related activities to avoid ever really facing greater scrutiny of the broker-dealer model and how their advice is implemented in the first place?

Dodd-Frank Section 913 And The (Uniform) Regulation Of Financial Advice

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, Congress sought to shore up many of the Wall Street regulatory gaps that were viewed as having precipitated or exacerbated the crisis, including improving the financial stability of banks, formalizing more orderly liquidations of failed banks, placing limitations on mortgage lending to curtail predatory behaviors, and establishing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The reform effort culminated in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, or what is more commonly just known as “Dodd-Frank” today.

At the same time that Congress was trying to reform Wall Street, though, a growing awareness was emerging that the lines between (registered) investment advisers and broker-dealers was blurring. It was started with a proposed exemption for broker-dealers in 1999 (finalized in 2005) that would allow them to offer fee-based accounts without becoming RIAs, which was subsequently overturned when the Financial Planning Association (FPA) sued the SEC and successfully had the rule vacated in 2007 on the grounds that the SEC had exceeded its authority to grant such a wide exemption for broker-dealers to avoid having a fiduciary duty to their clients while providing fee-based accounts. In the year that followed, the hybrid broker-dealer/RIA movement was born in response (as broker-dealers had no choice but to spin up a corporate RIA to offer fee-based advisory accounts at that point).

Yet while the FPA lawsuit succeeded in at least requiring broker-dealers to register as investment advisers to offer fee-based advisory accounts alongside their brokerage services, consumers arguably just became even more confused about the difference between broker-dealers subject to a suitability standard and RIAs subject to a fiduciary standard when firms literally started to offer both at the same time.

Accordingly, by the time Dodd-Frank was being considered, the Financial Planning Coalition and other organizations that support a fiduciary duty for financial advisors began to advocate and lobby for the SEC to formally adopt a “uniform” fiduciary duty for all brokers and investment advisers who were providing advice. Ultimately, Wall Street lobbyists managed to block the measure, culminating instead in Section 913 of Dodd-Frank which merely advocated that the SEC should do a(nother) study to affirm that there was a regulatory gap in the first place (akin to a similar study commissioned back in 2006, known as the “RAND Report”). A year later, the SEC issued the results of its study, which not surprisingly affirmed the problem (already cited in the RAND Report) and recommended (again) that a Uniform Fiduciary Standard, both for protection of consumers, and to “harmonize” the overlapping regulatory complexities between broker-dealers and RIAs.

Unfortunately, though, even after the Section 913 study, the SEC remained unwilling to take up regulatory reform of financial advisors, just as they had declined to do after the RAND Report. At least, until the Department of Labor proposed and issued its own fiduciary rule (proposed in 2015 and finalized in 2016), which impacted some – but not all – advisors and brokers under the SEC’s jurisdiction (given that it applied to retirement but not ‘normal’ taxable brokerage accounts), and then states began to implement their own fiduciary rules once the DoL rule was called into question (starting with a Nevada fiduciary proposal last fall and quickly spreading to more state-level initiatives).

As a result, even Wall Street began in the past year to lobby for the SEC to take action – after blocking regulatory reform efforts for a decade – ostensibly because they deemed it better to have uniform regulation (even if a little more stringent than the status quo today) than the risk of patchwork and piecemeal regulatory efforts (e.g., DoL applying to some but not all accounts, or states applying a fiduciary rule for brokers in that state but not necessarily others). Which has now culminated in the announcement last week that the SEC would be moving forward with its own effort to lift the standards that apply to financial advice across brokers and investment adviser.

SEC Proposes New Advice Rules Including Regulation Best Interest And Disclosure Form CRS

On Wednesday April 18th, the SEC issued a series of three new proposals, under what it is calling an effort to “Enhance Protections and Preserve Choice for Retail Investors in Their Relationships With Investment Professionals”, or what the industry has quickly dubbed the “SEC Advice Rule”.

Notably, notwithstanding the regulatory history leading up to it over the past decade, the new SEC Advice Rule proposals are not actually the “uniform” fiduciary standard that has long been discussed, and advocated for by many. Instead, the SEC has opted at this point to keep the regulation of broker-dealers separate from the fiduciary rule that applies to RIAs, but is proposing to lift the standard for broker-dealers to at least be closer to an RIA’s fiduciary duty, while also making a few potential refinements to RIAs (where their requirements are actually lower than broker-dealers), and improving consumer disclosures about the differences between the two.

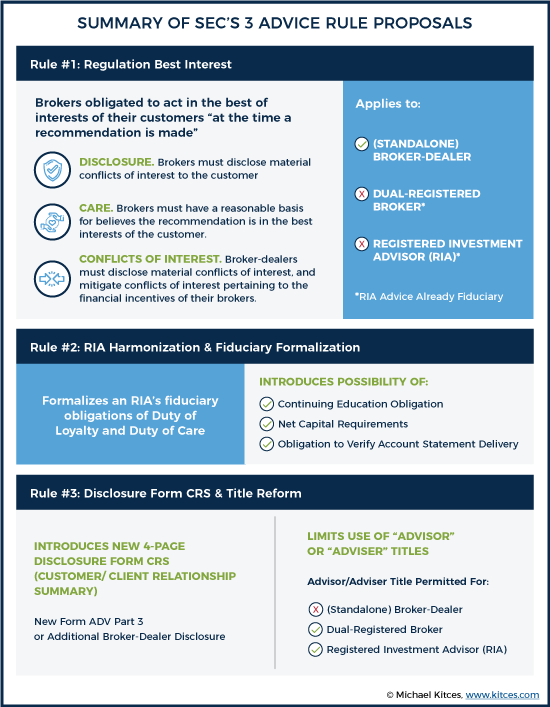

Specifically, the SEC Advice Rule has four main initiatives across three specific proposed rules that would apply to the IABD (Investment Adviser and Broker-Dealer) community:

- Regulation Best Interest would require brokers making a recommendation to a retail customer to act “in the best interests of the retail customer at the time the recommendation is made, without putting the financial or other interest of the broker-dealer ahead of the retail customer.”

- RIA Harmonization & Fiduciary Formalization would potentially add a requirement for investment adviser representatives of RIAs to get ongoing Continuing Education credit, introduce a minimum net worth or capital requirement to operate an (SEC-registered) investment advisory firm, and require RIAs to better affirm that clients are receiving regular quarterly advisory account statements.

- Disclosure Form CRS would be a new standardized short-form (4 page) disclosure that all broker-dealers and investment advisers would be required to provide to clients (in addition to other existing broker-dealer and RIA disclosures), providing a “relationship summary” of the key points of the relationship, including the services to be provided, the fees and other costs that may be incurred, and the standard of care that the advisor would be subject to.

- Advisor/Adviser Title Reform that would limit brokers at standalone broker-dealers (but not hybrid broker-dealers) from using any title that includes the word “advisor” or “adviser”, as an extension of the requirement for updated and more accurate disclosures under the Form CRS proposal.

As the SEC notes, the ultimate goal of these proposals it both to “enhance investor protection”, and to “preserve investor access/choice” (i.e., a choice between the transactional services of broker-dealers and the advice services of RIAs), while attempting to raise retail investor awareness of who they’re transacting business with in the first place. Since, as the SEC points out, “without sufficient clarity, retail investors may be more deferential to, or place greater reliance on, their broker-dealer or investment adviser than they otherwise would.”

SEC Proposes “Regulation Best Interest” For Broker-Dealers (Release No. 34-83062)

In Release No. 34-83062 (File S7-07-18), the SEC formally released its proposed rule “Regulation Best Interest” for broker-dealers, which would create a new standard under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 that brokers make recommendations to clients that are “in the best interests of the retail customer at the time the recommendation is made, without putting the financial or other interest of the broker-dealer ahead of the retail customer.”

Notably, the actual text of the new proposed Section 240.15l-1 (Regulation Best Interest) is relatively short, amounting to not even two full pages, although the supporting details of the proposed rule include a whopping 407 pages of explanatory material, including the background context of the rule, interpretations of all the key provisions, and the SEC’s cost/benefit analysis of the rule’s potential impact.

At its core, Regulation Best Interest determines whether the broker has met his/her “Best Interests” obligation with a 3-pronged test:

1) Disclosure. The broker is required, prior to or at the time of recommendation, to disclose (in writing) the material facts relating to the scope and terms of the relationship with the customer, including all material conflicts of interest that are associated with the recommendation.

2) Care. The broker must exercise reasonable diligence, care, skill, and prudence to:

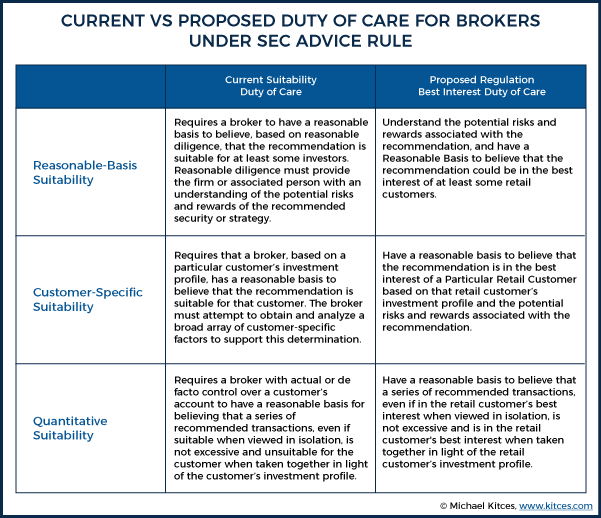

- Understand the potential risks and rewards associated with the recommendation, and have a Reasonable Basis to believe that the recommendation could be in the best interest of at least some retail customers

- Have a reasonable basis to believe that the recommendation is in the best interest of a Particular Retail Customer based on that retail customer’s investment profile and the potential risks and rewards associated with the recommendation; and

- Have a reasonable basis to believe that a series of recommended transactions, even if in the retail customer’s best interest when viewed in isolation, is not excessive and is in the retail customer’s best interest when taken together in light of the retail customer’s investment profile

3) Conflicts Of Interest. The broker-dealer will have obligations to disclosure and in some cases mitigate or eliminate conflicts of interest, including to:

- Establish, maintain, and enforce written policies and procedures reasonably designed to identify and at a minimum disclose, or eliminate, all material conflicts of interest that are associated with such recommendations.

- Establish, maintain, and enforce written policies and procedures reasonably designed to identify and disclose and mitigate, or eliminate, material conflicts of interest arising from financial incentives associated with such recommendations.

Notably, in its Regulation Best Interest (Regulation BI) proposal, the SEC explicitly noted that its intent in rolling out Regulation Best Interest was to make it reasonably conform to the existing systems and oversight infrastructure already in place for broker-dealers. Accordingly, the determination of when a “recommendation” is being made to a retail customer will be the same as it currently is under FINRA oversight rules (i.e., “whether the communication reasonably could be viewed as a ‘call to action’” or “reasonably would influence an investor to trade a particular security or group of securities”), disclosures will largely follow the existing rules and framework for broker-dealer disclosures (with the addition of new Disclosure Form CRS, as discussed later), and oversight can be conducted using risk-based systems already common in broker-dealers (as opposed to an obligation to review every transaction and recommendation).

In fact, the entire Best Interests standard of Care proposed under Regulation BI is literally the current “Suitability” standard for brokers, simply removing the word “suitability” and re-applying the word “best interests” instead, but retaining the three core components of FINRA Rule 2111.05: a “reasonable basis” obligation (that the recommendation could be in the interests of any customer, and the broker must understand what he/she is recommending in the first place), a “customer-specific” obligation (that the recommendation is appropriate for a particular customer, which the SEC explicitly states does not require doing a full financial plan to determine), and a “quantitative suitability” obligation (that the aggregate recommendations to the particular customer are appropriate, to curtail questionable behaviors like churning and aggressive switching).

Furthermore, the SEC went out of its way to emphasize that Regulation Best Interest is not intended to curtail the existing business model of broker-dealers, and emphasizes that fulfilling the broker’s Best Interests obligation is not about finding the absolute lowest cost (or least remunerative, or no-load) recommendation, nor to find the single “best” possible solution that could ever be recommended; instead, the obligation is simply to take reasonably diligent steps to affirm that the recommendation would be in the Best Interests of the customer (though situations like recommending an identical alternative at a higher cost when a lower-cost option was available would clearly still be a violation).

To further emphasize the point that Regulation Best Interests is not intended to limit the current broker-dealer model, it’s notable that the first prong of the Conflicts of Interest test itself does not require broker-dealers to mitigate their conflicts of interest at all, but to simply disclose all material conflicts of interest that they don’t (voluntarily) choose to eliminate. And indeed, in its Regulation Best Interest proposal guidance, the SEC explicitly listed various broker-dealer transactions that may potentially give rise to a conflict of interest but would not necessarily or automatically be banned under Regulation Best Interest (though the broker would still have to otherwise meet the Best Interest standard for the recommendation itself), including:

- Charging commissions or other transaction-based fees;

- Receiving or providing differential compensation based on the product sold;

- Receiving third-party compensation;

- Recommending proprietary products, products of affiliates or a limited range of products;

- Recommending a security underwritten by the broker-dealer or a broker-dealer affiliate, including initial public offerings (“IPOs”);

- Recommending a transaction to be executed in a principal capacity;

- Recommending complex products;

- Allocating trades and research, including allocating investment opportunities (e.g., IPO allocations or proprietary research or advice) among different types of customers and between retail customers and the broker-dealer’s own account;

- Considering cost to the broker-dealer of effecting the transaction or strategy on behalf of the customer (for example, the effort or cost of buying or selling an illiquid security); or

- Accepting a retail customer’s order that is contrary to the broker-dealer’s recommendations

Nonetheless, it is notable that while Regulation Best Interest would only require broker-dealers to disclose their own conflicts of interest, they would be required to “disclose and mitigate, or eliminate” conflicts of interest pertaining to the financial incentives of brokers. Or stated more simply, while broker-dealers themselves won’t necessarily be required to change their business models, they will likely still be expected to curtail at least some of the worst financial incentive abuses in the industry, and the SEC specifically raises caution about broker-dealers that have firm sales quotas, firm-sponsored sales contests, or differential/variable compensation or other incentives tied to appraisals or performance reviews (not to mention the very nature of product commissions themselves).

Though the SEC still takes pains to emphasize that the proposal is still only limited to “material” conflicts of interest, that arise from financial incentives of brokers, and that are specifically associated with a recommendation, and not pertaining to the rest of the broker-dealer’s financial activities with customers. In addition, the SEC even requested comment about the possibility that broker-dealers might be allowed to exercise investment discretion on a temporary or limited basis while still only being deemed “incidental” advice (akin to its failed prior attempt to expand fee-based advice to broker-dealers without being required to register as investment advisers!).

Perhaps most significant, though, was the SEC’s declaration under Regulation Best Interest that the entire framework would not apply to dual-registered (or hybrid) B/D-RIA firms, recognizing that as a fiduciary RIA the firm would already be required to disclose its various conflicts of interest and ostensibly take steps to mitigate those conflicts of interest. Thus, in practice, the entire Regulation BI framework applies only to standalone broker-dealers (that provide recommendations to retail customers), and not the (majority of) brokers operating as dual-registered or hybrid advisors (as to the extent any business is executed by the broker-dealer, it is presumed to be only in its “execution” capacity, since the “advice” was rendered while wearing the advisor’s “RIA” hat).

SEC Proposes Fiduciary Formalization & Enhanced “RIA Harmonization” Regulatory Requirements

While the primary focus of the SEC’s advice rule is on raising the standards that apply to brokers giving advice recommendations to retail customers, in an attempt to at least partially (albeit not fully) “harmonize” the regulations between brokers and investment advisers, the SEC’s Advice Rule also includes a series of prospective proposals in Release No IA-4889 (File No. S7-09-18) that would lift certain standards for (SEC-registered) investment advisers where they fall short relative to the requirements that already apply to broker-dealers.

The key areas of the “RIA Harmonization” proposal include:

- Federal Licensing For RIAs? Technically, RIAs currently pass a Series 65 (or waive out of it with certain designations) and get licensed at the state level; the SEC is considering whether to have a Federal licensing requirement for RIAs as well.

- Continuing Education For RIAs? Currently, investment adviser representatives do not have any continuing education requirements, while even FINRA registered representatives have at least basic FINRA CE requirements; accordingly, the SEC is considering whether to require IARs to obtain periodic CE.

- Providing Account Statements? Most RIAs use third-party custodians that provide statements to clients, but not all RIAs use a qualified custodian, and/or are not necessarily responsible for affirming that the custodian is fully and properly providing statements to clients, including details regarding fees and expenses the client may have incurred; the SEC raises the question of whether regulations should be more stringent in this regard, for RIAs to provide such statements to clients (or at least affirm that custodians are sending them), regardless of whether the RIA has custody or not.

- RIA Capital Requirements? Under Securities Exchange Act Rule 15c3-1, broker-dealers are required to maintain certain net capital requirements, to ensure that they can be efficiently liquidated in an orderly manner in the event the firm experiences financial stress, in addition to being members of SIPC and obtain a fidelity bond; however, most RIAs have no such requirements (unless imposed at the state level) beyond disclosing to a client if they have a material financial condition that might impair their ability to provide services. Accordingly, the SEC is considering whether to apply net capital requirements to RIAs, in perhaps the form of a net worth requirement or a fidelity bond.

Thus far, the proposals above are simply that – proposals – and the SEC has explicitly requested extensive comments and feedback regarding these potential new RIA requirements. Nonetheless, arguably none of these proposals should be deemed surprising.

In point of fact, RIAs are the only major channel of advisors (or incidental advice-providers) that don’t have at least some Continuing Education requirement, as both insurance agents, FINRA-registered representatives, and those with professional designations and other licenses (e.g., CFP certificants, CPA licensees) have annual or bi-annual CE requirements. And the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA) recently issued its own survey on the potential rollout of state-level CE requirements for RIAs as well. For most advisors, the only question will be whether the new RIA CE credits can be cross-applied to other CE requirements (e.g., for state insurance, FINRA, or CFP CE credits), or conversely whether the CE credits for those other licenses and designations will cross-apply for RIA CE. Although ironically, perhaps the biggest question about RIA CE will simply be how the SEC can expect RIAs to have continuing education requirements where there is no substantive upfront educational exam requirement in the first place (beyond the relatively simple Series 65, which tests the laws about RIAs delivering advice but not the actual knowledge to deliver advice).

In the case of delivering account statements, most financial planners who are structured as RIAs (or hybrid RIAs) likely already use a bona fide third-party custodian that regularly sends account statements already, for which there would be relatively little impact.

Perhaps the most potentially disruptive RIA harmonization proposal would be the potential for additional “financial responsibility” requirements for at least SEC-registered investment advisers (as the new rule wouldn’t necessarily apply to state-registered firms, unless the states separately choose to adopt the SEC’s new guidelines). Arguably, though, it really is reasonable for consumers to have some expectation that an advisory firm can “make good” on its service and financial commitments to clients (including their ability to have financial recourse for inappropriate behavior and damages caused), whether it’s through some combination of the RIA’s net capital requirement, or a fidelity bond, or simply E&O insurance. In fact, the SEC raises the question of whether it should simply follow the existing NASAA Model Rule 202(d)-1 on minimum financial requirements for RIAs, which would require a minimum net worth of $35,000 for firms with custody, $10,000 for firms that have discretion (but not custody), and a “positive” net worth for firms that accept a prepayment of more than $500 per client that is six-or-more months in advance (to ensure the firm can refund any unearned fees in the event of termination). Relative to the typical financial position of an SEC-registered investment adviser (with more than $100M under management), these would/should not be onerous financial requirements for most (especially given the reasonable consumer protections they provide).

Formalizing An RIA’s Fiduciary Obligation

In addition, the RIA Harmonization proposal also aims to formalize much of the fiduciary duty that applies to RIAs themselves, given that technically an RIA’s fiduciary obligation stems not directly from the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, but the interpretation in the famous 1963 Supreme Court case of SEC v Capital Gains Research Bureau that the “anti-fraud” requirements of Rule 206(4) of the '40 Act that advisors cannot be fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative in how they hold out to consumers would effectively mean they have a fiduciary duty to their clients.

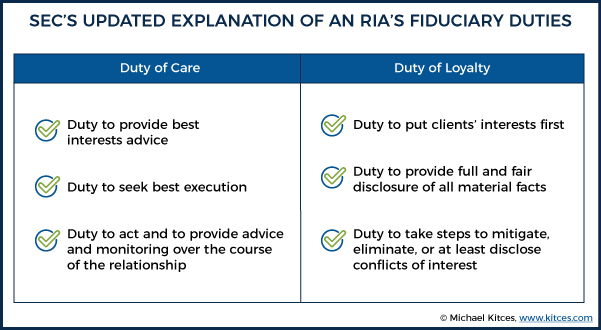

Accordingly, just as Regulation Best Interests would formalize the terms of the (proposed) Best Interests standard for broker-dealers, Release No IA-4889 (File No. S7-09-18) would formalize the fiduciary duties of RIAs, which specifically would include:

- Duty of Care. Fiduciaries have a Duty of Care to their clients (in addition to a Duty of Loyalty) that they actually take steps to ensure that the advice they’re providing for their clients actually is the right and proper advice, which would include:

- Duty to Provide Best Interests Advice. When providing personalized investment advice, the investment adviser would have a duty to make a reasonable inquiry into the client’s financial situation, level of financial sophistication, investment experience, and investment objectives, beyond making a recommendation (with the breadth of diligence based on the breadth and scope of the advice engagement).

- Duty to Seek Best Execution. To the extent that the investment adviser manages the client’s portfolio and has a duty to select broker-dealers for execution and actually facilitate execution of client trades (e.g., with discretionary accounts), the RIA has a duty to seek best execution for those client transactions.

- Duty to Act and to Provide Advice and Monitoring over the Course of the Relationship. Once an advisor provides advice, they have a duty to follow through and subsequently monitor the implementation of that advice (e.g., to monitor a portfolio over which they have discretionary management), although to the extent that the scope of the relationship is limited (e.g., to a one-time financial plan), the scope of monitoring would be limited to the duration of the actual (limited) relationship.

- Duty of Loyalty. The duty of loyalty is the obligation of a fiduciary to put their clients’ interests first, and not favor its own interests, including providing full and fair disclosure of all material facts relating to the advisory relationship, and taking steps to avoid or at least make fair disclosure of any conflicts of interest.

Notably, the SEC’s formal definitions of an RIA fiduciary’s duty of care and duty of loyalty, and what they entail, are not substantively different than the existing SEC guidance and court cases that have already occurred in the past with respect to the fiduciary duty; they are simply intended to formalize in regulation the scope of the RIA’s already-existing fiduciary duty.

SEC Advice Rule Proposes New Disclosure Form CRS For B/Ds And RIAs

Given the ongoing series of consumer studies showing that most retail investors still don’t even understand the differences between broker-dealers and registered investment advisers, the last major component of the SEC’s Advice Rule proposals is the creating of a new Disclosure Form CRS – short for Customer/Client Relationship Summary (the SEC uses both terms, recognizing that broker-dealers have transactional “customers” while RIAs have ongoing “clients”) – and the new form is intended to clarify for consumers both “who” they are dealing with, and “why” it matters.

The new Disclosure Form CRS would have 8 standardized sections contained on a no-more-than-4-page form that every representative of a broker-dealer or RIA would be expected to provide to every customer/client, either before doing business with them or at the time of engagement. Advisors would be expected to use “plain language”, including being “concise and direct… [using] short sentences, active voice, and definite, concrete, everyday words” across each of the 8 areas, which include:

Section 1: Introduction: Provides essential firm information, including whether it is registered as a broker-dealer, RIA, or both, along a brief explanation of the types of accounts (brokerage or advisory) that it offers, with mandatory language such as “We are a broker-dealer and provide brokerage accounts and services rather than advisory accounts and services” or “We are an investment adviser and provide advisory accounts and services rather than brokerage accounts and services” for broker-dealers and RIAs, respectively.

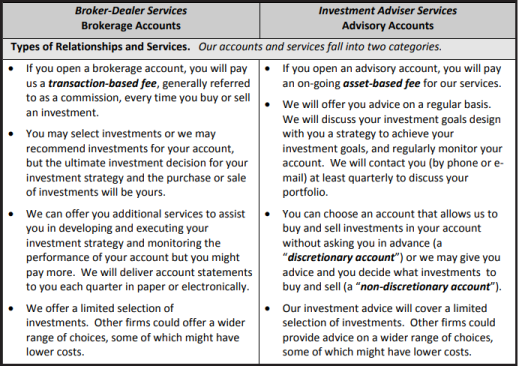

Section 2: Relationship and Services: Provides further detail about the advisory or brokerage account services the firm provides, including a clear articulation “If you open a brokerage account, you will pay us a transaction-based fee, generally referred to as a commission, every time you buy or sell an investment” for broker-dealers or “If you open an advisory account, you will pay an ongoing asset-based fee for our services” (or whatever fee model the firm uses) for RIAs.

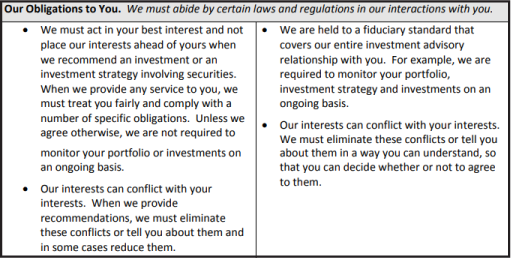

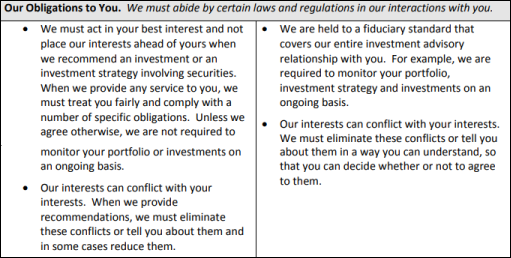

Section 3: Standard of Conduct: With the label “Our Obligations To You”, this section would start with mandatory language “We must abide by certain laws and regulations in our interactions with you” and then either specify the Best Interests standard that would apply for a brokerage relationship (stating “We must act in your best interests and not place our interests ahead of yours when we recommend an investment or an investment strategy involving securities” or the fiduciary standard that would apply to an RIA relationship (stating “We are held to a fiduciary standard that covers our entire investment advisory relationship with you”).

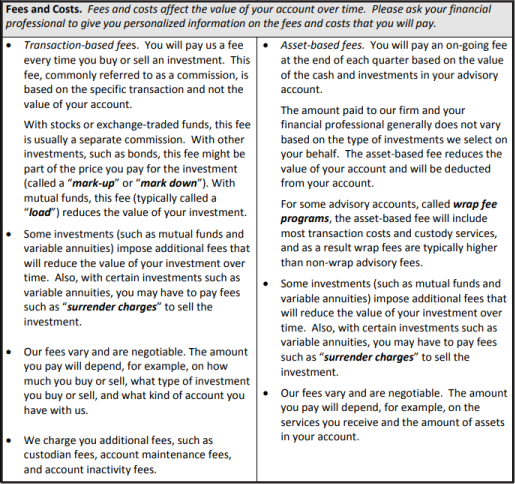

Section 4: Summary of Fees and Costs: Includes an overview of the types of fees or other expenses that investors might incur, including a description of transaction-based fees (e.g., potential for commissions and loads, or mark-ups and mark-downs, surrender charges, etc.) or any asset-based or other advice fees (e.g., advisory fees, wrap fees, any underlying trading costs, etc.).

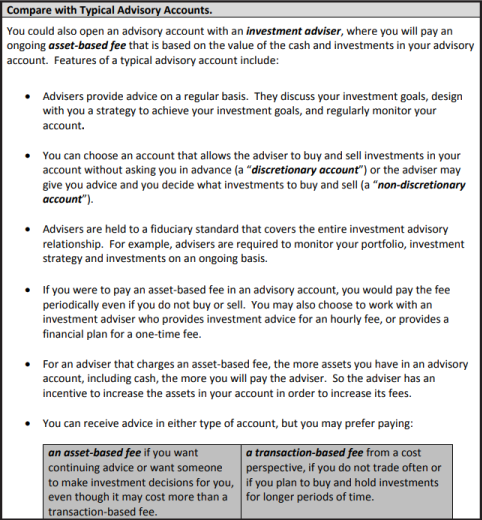

Section 5: Comparisons To Other Account Types: For a standalone broker-dealer or RIA, a description of the “other type” of account options (i.e., RIAs would need to explain how brokerage accounts compare, and broker-dealers would need to explain how advisory accounts compare), with standard language prescribed by the SEC for each. This section would not apply to hybrid firms, as both types of accounts would already have been explained as options in Section 2.

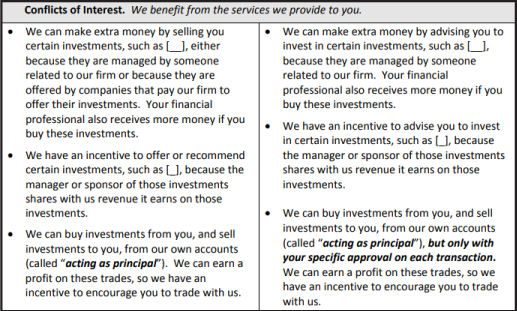

Section 6: Conflicts of Interest: Firms must disclose their conflicts of interest related to financial incentives, particularly at the firm level (e.g., proprietary products, principal trading, etc.), although the section is not intended to be a comprehensive list of all possible conflicts of interest (which would be detailed further in standard supplemental disclosures that both broker-dealers and RIAs must provide).

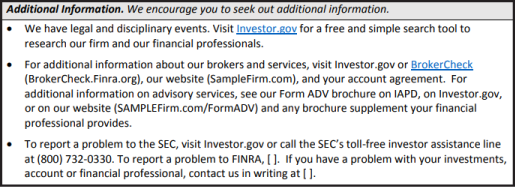

Section 7: Additional Information: Guidance on where to find additional information (e.g., IAPD or BrokerCheck), including an outright declaration if the firm has any disciplinary events that must be disclosed (though the firm can direct investors to IAPD or BrokerCheck for the exact disciplinary event details).

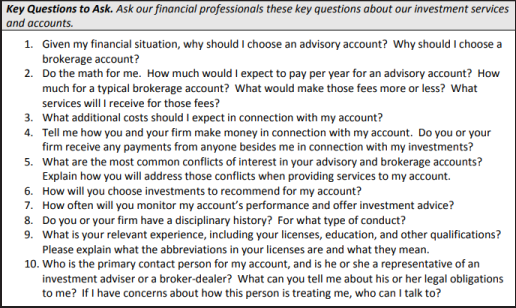

Section 8: Key Questions to Ask: Which would provide a series of 10 standardized questions, prescribed by the SEC, that consumers are encouraged to ask, including further detail about cost comparisons between brokerage and advisory accounts, how the firm makes money, conflicts of interest, how the firm will choose and monitor investments, etc.

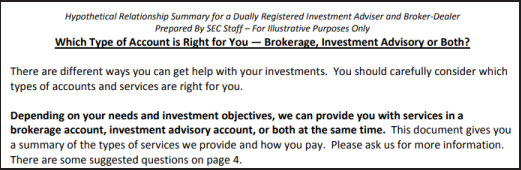

To further illustrate expectations of Form CRS, the SEC provided sample versions of Form CRS for both a standalone broker-dealer, a standalone RIA, and a dual-registered broker-dealer/RIA firm.

For broker-dealers, Disclosure Form CRS would be a newly created form that the broker-dealer would deliver separately; for RIAs, it would become a new “Form ADV Part 3”. Similarly to other disclosures, the SEC stipulates that it may be delivered in paper format, or via PDF, or in a more interactive digital format (as long as the key elements are still included). It would also be filed online, either in the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD) for RIAs, or via the EDGAR system for broker-dealers (though it’s not clear if consumers will be able to access that information directly via IAPD or BrokerCheck when evaluating individual advisers and brokers). Firms would be expected to file an updated version of Form CRS within 30 days of a material change.

Ultimately, the primary goal and purpose of Form CRS is to help clarify the differences between broker-dealer and RIA relationships, although notably the template forms are tilted heavily towards the underlying nature of brokerage versus advisory accounts, and not as much towards the transactional-sales vs (ongoing or onetime) advice nature of the broker-dealer versus advisory relationship itself. Notwithstanding the fact that the SEC itself acknowledges and recognizes in its proposal that broker-dealers work with “customers” and RIAs work with “clients” (though ironically that distinction itself is never made on the SEC’s Form CRS templates)! Nor is it clear that consumers will understand the new distinction between “broker-dealers subject to a best-interest standard” and “RIAs subject to a fiduciary standard” especially given that the fiduciary standard is typically defined as a “best interests standard” itself!

SEC Advice Rule Would Restrict Use Of Advisor And Adviser Titles (For Standalone Broker-Dealers)

While the new Disclosure Form CRS is intended to help “clarify” the relationship between a customer or client and their broker or investment adviser, ultimately the SEC acknowledges that consumers will already have certain expectations of the relationship based on how the advisor or broker held themselves out to the public in the first place. In particular, the SEC recognizes that once brokers market themselves as advisors it may be difficult for consumers to recognize that he/she isn’t actually an advisor after all (based on the subsequent Form CRS explaining that it is actually a brokerage relationship). An issue that was recognized in both the RAND Report and the SEC’s own Dodd-Frank Section 913 study.

Accordingly, an extension of the Release No. 34-83063 proposal explicitly would require that brokers not use the words “advisor” or “adviser” (with either spelling) when holding out to the public, including longer titles that include those words (e.g., financial advisor, investment advisor, wealth advisor, etc.). Notably, though, the SEC proposes to only regulate the words advisor/adviser, and not other similar titles like financial consultant, wealth manager, etc., suggesting that it’s the advisor label in particular that is most similar to “investment advisers” and thus most prone to creating consumer confusion.

However, the SEC has declared that the limitation on advisor/adviser titles will only apply to standalone broker-dealers and their registered representatives; dual-registered or hybrid advisors who are affiliated with both an RIA and a broker-dealer will still be permitted to use the label (regardless of which “hat” they are wearing at the time), as the SEC decided that it would potentially be even more confusing for consumers to engage with advisors whose titles change and that they might misunderstand that a broker using a broker title also provides advice services beyond their capacity as a broker (though ironically, the SEC apparently didn’t fret a consumer misunderstanding that an advisor might also be providing lesser-standard brokerage services beyond their capacity as an adviser?). In addition, the new limits on the use of titles would not apply to insurance and annuity agents, who fall outside of the SEC’s regulatory purview.

Notably, the SEC indicates that it did consider a rule where using the title “advisor” itself would mean that any/all advice is no longer solely incidental (which would force all brokers using the title to simply become RIAs), or a “holding out” rule that advisors marketing any advice-like service would trigger RIA registration, but ultimately expressed concern that such a path would create more regulatory uncertainty due to the difficulty in articulating exactly which activities/services would be permissible as a broker or not.

Implications Of The New SEC Advice Rule Proposals For Financial Advisors

At a high level, the biggest impact of the SEC’s new Advice Rule is that it would lift the standard of care for brokers, from merely requiring that recommendations be “suitable” for the client’s circumstances, to recommendations that are in the client’s “best interests” instead. At least, in the moment of making the recommendation itself (which is when Regulation Best Interests would apply). And the SEC’s rule would apply uniformly across all types of investment accounts (albeit not annuity recommendations, which fall outside the SEC’s purview for fixed and indexed annuities), which is arguably a significant improvement from the DoL’s fiduciary rule that was limited to “just” retirement accounts.

Notably, the SEC took significant pains to conform its proposals to the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule as well, or at least be clear in its explanations where it may have deviated and why. Which speaks to the significance of the DoL fiduciary rule and its impact… even if ultimately vacated by the Fifth Circuit’s Appeals Court ruling, it still substantially influenced the SEC’s proposal.

Uniform Fiduciary Standard Vs Separating Sales From Advice?

Nonetheless, it’s still notable for what the SEC’s advice rule does not accomplish. First and foremost, it is not actually an “SEC Fiduciary” rule. In fact, the SEC went out of its way to not propose a fiduciary rule for broker-dealers, nor to establish a “uniform” fiduciary standard that would fully harmonize broker-dealer and RIA regulation as prescribed under Section 913(g) of Dodd-Frank; instead, the SEC merely relied on the lesser Section 913(f) of Dodd-Frank, which authorized the SEC to engage in rulemaking pertaining to broker-dealers without a full fiduciary (or uniform) standard for the advice they may provide.

In point of fact, though, I would actually (and perhaps controversially) argue that this is a good outcome, even as one who advocates strongly for a fiduciary duty for financial advice. As while I do believe the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule was a positive step forward from the status quo of the time, I have long advocated that a “uniform” fiduciary rule for broker-dealers and investment advisers is not the ideal outcome. The reason, simply put, is that some consumers really do just want someone to engage in transaction business with, for which they should have easy access to commission-based transactional (non-advisory) accounts.

The key distinction, though – that even the SEC appears not to have fully embraced – is that brokerage business is a transactional sales business, as distinct from the business of providing advice. Thus why Congress, under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, requires that anyone in the business of providing investment advice for compensation must register as a (fiduciary) investment advice, from which broker-dealers are exempt only if any advice they give is “solely incidental” to their sale of brokerage services.

In other words, the real debate should never have been about whether brokers should be subject to a suitability or fiduciary standard; instead, it’s really about (re-)asserting a clear bright line between sales (in a brokerage relationship) and advice (in an advisory relationship). Just as Congress established nearly 80 years ago when they separated sales (brokerage) from advice (RIAs) with the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Where it was never about brokers being held to a fiduciary standard; it was about brokers being clear they’re not advisors.

And in this context, arguably the SEC’s advice rule does a substantial disservice to consumers. As not only does the SEC expand the leeway for broker-dealers to give advice, potentially beyond the solely incidental exception for broker-dealers that Congress prescribed in the first place, but it co-opts the label of the “Best Interest” standard in the first place. After all, as the SEC’s own sample Disclosure Form CRS shows, broker-dealers “must act in the [client’s] best interests” while RIAs are “held to a fiduciary standard”… which the SEC defines as “the highest standard of conduct [where the investment adviser] must act in the best interest of its client.”

How are consumers supposed to understand the difference between a “Best Interests” standard for brokers, and a “fiduciary standard to act in the best interests of the client” for RIAs!? Technically, the real distinction in the SEC’s templated Form CRS language is that brokers are only subject to a Best Interests standard “when recommending an investment or an investment strategy” while RIAs are fiduciaries “in our entire investment advisory relationship”. Which raises the question – is there really such thing as being as acting in the clients’ best interest only some of the time?

Oddly, the SEC seems to imply this is an expected outcome, going so far as to state at one point that brokerage is a “pay as you go” model for advice. In fact, the SEC repeatedly suggests that a better way to delineate between brokers and investment advisers is not sales versus advice, but transactional advice versus ongoing advice… apparently ignoring the clear framework from the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 that brokerage firms can only provide incidental advice to transaction sales, not transactional pay-as-you-go advice, in what appears to be an effort by the SEC to even further expand the “solely incidental” advice exception for brokers?

Making Title Reform (More) Meaningful?

On the plus side, the SEC’s Advice Rule does take a positive step towards clarifying the separation between sales and advice, by explicitly requiring that (standalone) broker-dealers not use the “advisor” or “adviser” titles.

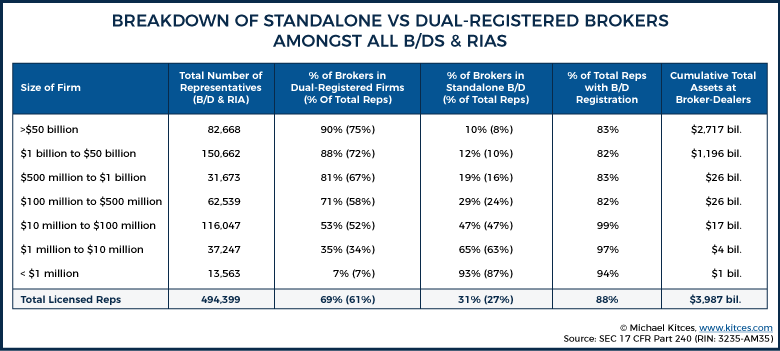

However, in practice, the new standard for titles is very weak... because it only applies to standalone broker-dealers and not to dual-registered brokers who are also under an RIA! Which is important, because according to the SEC’s own data in its cost/benefit analysis, because brokers comprise nearly 88% of the total headcount of brokers and investment advisers, and nearly 70% of those brokers are dual-registered as RIAs as well, while only 30% of brokers are actually in a standalone broker-dealer in the first place. Which is even more important on an asset-weighted basis, as the overwhelming majority of all client assets are held at the largest firms!

In other words, the “advisor/adviser” title reform – and the new Regulation Best Interest rules themselves – would not actually apply to nearly 70% of all brokers, and an even higher percentage of client assets that those brokers oversee (and potentially provide advice upon).

Despite the fact that, by the very nature of the dual-registered relationship itself, the hybrid broker is not a fiduciary giving advice at all times (unlike the CFP Board’s recent changes to its own Standards of Conduct), and the SEC acknowledges the nature of the “dual-hatted” relationship that dual-registered brokers have with their clients. In fact, ironically the SEC even emphasized that it was concerned that establishing a separate title for dual-registered brokers may incorrectly cause consumers to believe the broker was only always a broker… without acknowledging that by permitting the title for both advisor-at-all-times (under an RIA) and advisors-some-of-the-time (as a dual-registrant) consumers may be equally confused about when a broker is and isn’t acting as an advisor.

Or stated more simply… will consumers actually be able to understand that brokers will only be providing Best Interests recommendation at certain points in time… while at other times they might still be subject to the suitability standard (when actually implementing the advice)? How exactly does an advisor properly communicate they are “un-advisor”ing themselves and relegating themselves to a lower regulatory standard for implementation?

Even more concerning, given that nearly 70% of brokers are already dual-registered… it seems likely that the broker-dealer community will simply expand their dual-registration approach, as the firms can simply spin up a corporate RIA, have their registered representatives take the Series 65, and then completely avoid both Regulation Best Interests and the title restrictions altogether by simply claiming that any limited-scope advice is being provided wearing the RIA hat… while the broker implements with the same brokerage sales hat they do today, subject to the same suitability standard that already exists, and which has already been recognized as inadequate (thus spurring the SEC’s Advice Rule in the first place!).

Near-Term Industry Impact Of The SEC Advice Rule

In theory, the near-term implications of the SEC’s Advice Rule is that broker-dealers will have to reform their compensation incentives for brokers under the new Regulation Best Interests standard – as while the proposed rules would not require broker-dealers to mitigate their actual conflicts of interest as a broker-dealer, they are required to take steps to mitigate the financial incentives of their brokers. Which could potentially at least curtail the most extreme commission payouts, along with aggressive sales quotes and especially lascivious sales contests for brokers.

Yet with the “loophole” that hybrid broker-dealers are not subject to the new Regulation Best Interest standard (or title reform), which already exempts nearly 70% of brokers and removes an even higher percentage of actual clients being served from any protections under the new rules, arguably the most likely outcome may simply be that even more broker-dealers launch corporate RIAs, require their representatives to pass the Series 65 exam, and then simply conduct “business as usual” by claiming all their advice is being provided wearing their RIA hat, while all product implementation still occurs under the broker-dealer (and without the new Regulation Best Interests protections).

As while the SEC suggests that Regulation Best Interests is ‘unnecessary’ for hybrid advisors who are already subject to a fiduciary standard when wearing their RIA hat, is the fiduciary standard for RIAs was sufficient to quell problematic brokerage firm behaviors, the problem would already be solved given that the overwhelming majority of clients are already being served by dual-registered brokers!

Which means arguably, the real “battleground” issue of the SEC’s Advice Rule is likely to be the very nature of dual-registration itself, and the question of whether the RIA fiduciary duty really does extend to a broker’s implementation of RIA-based advice, and whether Congress even contemplated that an RIA fiduciary who gives advice can “un-advisor”, “un-RIA”, and most importantly “un-fiduciary” themselves by switching hats in the midst of an ongoing advice engagement? After all, if Congress intended for most “advisors” to simply give advice as a (fiduciary) RIA and then implement as a (non-fiduciary) broker through dual-registration, they wouldn’t have carved out an exemption for brokers to give solely incidental advice in the first place?

90-Day Public Comment Period Open On SEC Advice Rule

Of course, it’s important to remember that thus far, the SEC’s Advice Rule proposals are just that – proposals, for which there will now be a 90-day Public Comment period. In fact, even the SEC Commissions themselves are still split on how to proceed, with the initial proposal itself only progressing after a 4-1 vote (as Democratic SEC Commissioner Kara Stein objected that brokers weren’t being subjected to a full fiduciary duty from the start), and SEC Chair Clayton himself stating that the proposal is simply intended to be an initial “path forward” for which he anticipates “robust” public comment!

Advisors who are interested in expressing their own views can submit comments directly, either to the SEC’s comments address at [email protected], or via the SEC’s online public comment submission tool. For those who wish to submit, be certain to reference the File No (which is S7-08-18 for Regulation Best Interest and Form CRS/Titles comments, and S7-09-18 for the RIA Harmonization proposals).

Ultimately, the SEC will take Public Comment feedback, and then decide whether to amend the proposed rule, re-propose it for further comment, withdraw it altogether, or to proceed with the rulemaking process… which in all likelihood still make not be completed earlier than late 2018 or early 2019, with an effective date to follow thereafter.

Nonetheless, for advisors who are interested in expressing their views on the SEC Advice Rule, it’s new Regulation Best Interest standard for brokers, the harmonization of certain regulatory requirements for RIAs, the new Disclosure Form CRS, the limitations on the use of the advisor/adviser titles, and the exceptions that will apply to all of these standards for the majority of brokers who are dual-registered anyway… now is the time to make your voice heard!

So what do you think? Is the SEC’s Advice Rule an improvement over the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule? What do you think the impact would be? Do you intend to submit a Public Comment? Please share your initial thoughts in the Comments below!

Leave a Reply