Executive Summary

The modern broker-dealer structure was created in the aftermath of the Crash of 1929, as the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 set forth new rules and registration requirements for the financial intermediaries that either were dealers in securities from their own investment inventory, or brokered securities transactions for their customers (including in subsequent decades the distribution of securities products, like mutual funds).

Yet in the coming years, the broker-dealer business model is under threat from the looming rollout of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, which at best will likely reduce upfront commissions and drive a shift towards more levelized compensation for advisors, and some predict may eventually eliminate product commissions altogether.

Notably, a world without commissions is not necessarily the death knell for advisors, as the reality is that the non-commissioned RIA segment of advisors has already been experiencing the greatest growth in recent years, and even the majority of brokers have indicated that they think it is reasonable to be required to give advice in the best interests of their clients.

However, the ongoing evolutionary shift of “financial advisors” from securities product salespeople to actual advisors is creating an existential crisis for broker-dealers – after all, in a future fiduciary world where advisors are paid directly by their clients for advice, what is the purpose or need for a broker-dealer intermediary at all?

Which means in the long run, for broker-dealers to survive and thrive, they will be compelled to reinvent their business (and revenue) models altogether, to remain relevant in a world of financial advisors that rely on them not as financial intermediaries to facilitate the distribution and sale of third-party or proprietary securities products, but financial advisor support platforms that help to facilitate the success of cadvisors who are actually paid for their financial advice!

The Purpose And Origins Of The Modern Independent Broker-Dealer

The modern version of the broker-dealer can trace its roots to the aftermath of the Crash of 1929, out of which came the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 – the legislation that created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the rules for securities exchanges themselves and how they operate, and the rules and registration requirements of broker-dealers.

As the compound name implies, broker-dealers existed to fulfill two primary functions: to execute securities trades in their own account as a dealer, and to execute securities trades on behalf of customers as a broker. Notably, at this time a broker-dealer was typically attached directly to an investment bank responsible for assisting companies in raising (i.e., issuing) debt and equity capital. Thus, the process of raising funds in capital markets would involve an investment bank facilitating the issuance of stocks and bonds, which would then be held in the inventory of the broker-dealer, and stockbrokers would then be responsible for selling the newly-issued securities from the broker-dealer’s inventory to investors.

In the decades following the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the scope of broker-dealers expanded to include the sale and distribution of an ever-widening range of registered securities products – beyond just the stocks and bonds in the broker-dealer’s inventory, or brokering trades on the securities exchanges on behalf of customers. Most notably, this included the rise of the mutual fund, a securities product that could be brokered (i.e., sold) by the representatives of a broker-dealer. In this context, the mutual fund would pay the broker-dealer a selling concession for distributing its product, a portion of which the broker-dealer would then pass along as compensation to the broker in the form of a sales commission.

The growth of mutual funds (and to a lesser extent, other registered securities products) was so successful that by the 1970s and 1980s, there was enough money to be made by just brokering the sale of securities products and generating commissions, that the independent broker-dealer model arose and became popular. The key distinction of the independent broker-dealer was that it generally had no direct affiliation to an investment bank or investment company, and thus was not selling its own proprietary stocks, bonds, or other securities products. Instead, independent broker-dealers sold third-party securities, independent of the company itself.

In turn, the rise of the independent broker-dealer meant the role of the broker-dealer shifted, from dealing in securities in its inventory (to sell to customers) or packaging securities products (to sell to customers), to instead be responsible for the oversight of the sale of third-party securities products, including vetting/evaluating the products for sale, managing and overseeing the sales process (i.e., compliance oversight of brokers), and collecting and allocating the sales commissions that were paid.

As the registered representatives of broker-dealers – both independent and “captive” insurance or wirehouse broker-dealers – sought to add value to clients, they have increasingly offered a range of financial advice to consumers as well, to the point that most who work at such firms now are variously called “financial advisors” or “financial consultants”.

Notwithstanding this shift, though, functionally the reality is that the “advisors” who work for broker-dealers are still legally in the business of selling (proprietary or third-party) securities products and offering related brokerage services. In fact, the legal reality is that an “advisor” ceases to be a broker and must become a fiduciary investment adviser if their advice offering ever becomes more than just “solely incidental” to the sale of securities products and the delivery of brokerage services!

Are Broker-Dealers Irrelevant In A Fiduciary Future Of Advice?

The fundamental challenge for broker-dealers as financial advice moves inexorably towards a fiduciary future is that the broker-dealer operates primarily to facilitate the sale and distribution of securities products. They were never built as platforms specifically to support the delivery of financial advice, particularly in a world where advisors are compensated directly for their advice via fees and not with commissions paid by securities product providers for the sale of their products (or commissions paid directly by the broker-dealer for the sale of its own proprietary products). In other words, if the future of financial advisors is to get paid for advice (not the sale and distribution of securities products), what’s the relevance of a broker-dealer that exists primarily to facilitate the sale and distribution of securities products?

In this context, it’s not entirely surprising that broker-dealers have been overwhelmingly negative regarding the Department of Labor’s fiduciary proposal, and likewise why broker-dealer companies have been more negative about the fiduciary rule than brokers themselves. Because the reality is that brokers have been increasingly shifting towards delivering financial advice – and actually creating value with their advice – for years now, and many brokers already try to give advice in the interests of their clients (which is really the only way that advice can be given to really be advice!).

Which means in a fiduciary future, if forced to do so, brokers-as-financial-advisors can finally complete the transition to become true financial advisors who get paid for advice instead of product distribution, and those with an advice skillset can survive and thrive in a fiduciary future. Broker-dealers, on the other hand, risk becoming irrelevant in an advice-centric world. Which means fighting the DoL fiduciary rule has become an existential crisis of survival for many (or even most) broker-dealers.

Conversely, what this also means is that for broker-dealers to survive in a fiduciary future, broker-dealers must evolve themselves from being platforms that facilitate the sale and distribution of third-party or proprietary securities products, to ones that actually support the success of financial advisors who deliver advice (and are compensated primarily for the value of their advice).

How The Best Broker-Dealers Will Reinvent As Advisor Platforms To Survive And Thrive

So what exactly does it mean to create a platform to serve and support advisors, rather than merely operating a broker-dealer to facilitate brokers selling third-party or proprietary securities products? The starting point is to look at how the non-product-centric side of the advisory industry has already been evolving in recent years.

For instance, RIA custodians seek to create appealing platforms for RIAs primarily through technology that supports their advisors. All RIA custodians have some form of comprehensive advisor technology stack that their advisors rely upon to operate their businesses – through various combinations of proprietary solutions, ‘preferred vendors’ with deep integrations, and/or creating an open architecture framework into which technology solutions can be plugged in. In a world where so much of the raw custody business has been brutally commoditized, custodian platforms increasingly differentiate on the basis of their technology.

Notably, though, the RIA advisor support ecosystem goes further than just how RIA custodians support their advisors. An interesting phenomenon of the advice industry, with its relationship-based recurring revenue business models, is that advice-based firms have grown far larger than the collection-of-silo’ed-brokers seen in the typical broker-dealer firm. This has led to everything from mega-RIAs that become so large, they themselves become a form of “advisor platform”, and those platforms are then grown via mergers and acquisitions, “tuck-in” deals, or even RIAs themselves offering third-party platform services to other advisors.

In this context, the function of the “advisor platform” is to help facilitate as much of the back-office operational functions, and even “mid-office” functions (e.g., investment and increasingly financial planning analysis) as possible, so that the advisors themselves can spend as much time as possible performing their highest and best use: interacting directly with clients, giving advice, and delivering value.

Accordingly, the “advisor platform” of the future might include not only technology solutions, but centralized back-office support (including operations and administrative support), centralized financial planning expertise (from an “Advanced Markets” sales support team to an “Advanced Planning” advice support team) and financial planning staff support (why should advisors need their own paraplanners when a central advisor platform can provide them on shared/pooled basis?), and even a Due Diligence department (not to vet products to be sold, but to meet the even higher burden of vetting products that will be recommended by fiduciary advisors). And of course, compliance – in a fiduciary context, not FINRA-style product sales oversight! – is also a highly relevant advisor platform function that benefits from scale.

Reinventing The Broker-Dealer Revenue Model - From Grid Payouts To Flat-Fee TFPP?

Ultimately, the greatest threat for broker-dealers may not be the fact that they must reinvent their service model to be relevant for advisors who get paid for advice (rather than brokers who get paid to distribute product) – it’s the fact that broker-dealers may soon be forced to reinvent their entire revenue model as well.

After all, if a fiduciary rule drives advisors away from product distribution and towards getting paid for advice itself, such that broker-dealers can no longer rely on their current role as an intermediary in the world of financial services product distribution, then broker-dealers will lose ‘access’ to everything from commissions with their revenue-sharing and override payment structures, to the “shelf space” agreements from product companies looking for distribution.

Perhaps some of this revenue will ironically be made up by financial services product companies that go from paying for distribution opportunities through revenue-sharing and shelf space agreements, to those product providers offering to sponsor advisor events and conferences to get visibility with fiduciary advisors and have their products considered as potential recommendations. (Again, when looking at parallels in the medical industry, drug companies continue to be heavy sponsors of conferences for doctors to build awareness of their products with the doctors who function as gatekeepers for their patients, even if the drug companies cannot pay commissions to doctors to use their drugs.)

To some extent, the transition towards fiduciary advice may simply mean a push away from ‘traditional’ upfront commissions, and towards levelized commissions akin to ongoing AUM fees. In the long run, this may not necessarily be problematic for broker-dealers. In fact, traditionally businesses with recurring revenue have better valuations, and in recent years the broker-dealers with more fee-based revenue have already commanded higher valuations than their purely-commission-based brethren.

However, just as financial advisors themselves often struggle with the transition from upfront commissions to levelized AUM fees – for instance, going from a 5% upfront commission to a 1% AUM may be more profitable in the long run (6+ years), but can cause a cash flow squeeze in the short term (getting paid 1% in year 1 instead of 5%!)– so too will broker-dealers face a potentially challenging revenue transition in the coming years if the Department of Labor fiduciary rule squeezes down the size of up-front commissions.

Perhaps even more problematic, though, is the prospective rise of non-commission or even non-AUM-fee advisor revenue models, and the question of where broker-dealers fit (or not) in that advice-centric advisor business model of the future. Whether it’s annual or monthly retainer fees, or even new forms of net-worth-and-income-based fee structures, how can broker-dealers get paid in a process where compensation typically goes directly from the client to the advisor (and not via the broker-dealer middle-man), and what is the reasonable amount for a broker-dealer-turned-“financial advisor platform” to be paid?

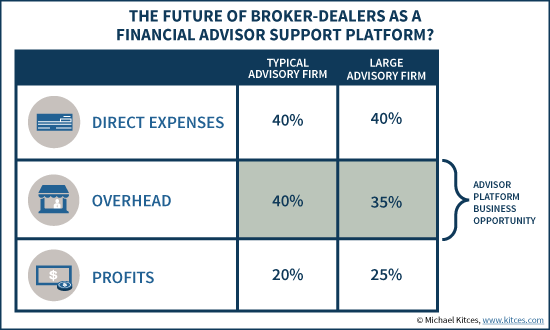

Industry benchmarking studies for independent advice-centric advisors show that the “typical” profit-and-loss statement for an advisory firm follows a roughly 40%/40%/20% split – where 40% is allocable to “Direct Expenses” (payments to advisors to provide advice), 40% goes to overhead, and 20% remains as a profit margin for the advisory firm. “Larger” advisory firms (which might still “only” be $1B of AUM and $10M of revenue, a fraction of the size of mid-to-large sized broker-dealers), which enjoy at least some economies of scale in their operations, may run a 40%/35%/25% split. Which means a fully scaled “advisor platform” that covers virtually all of the back- and middle-office overhead functions of an advisory firm could conceivably have a crack at perhaps 30% of an advisory firm’s revenue (given that a few expenses, like office space/rent, won’t likely be subsumed by the advisory firm platform).

In other words, the advisor platform of the future could potentially be relevant for as much as 30% of an advisor’s revenue, by providing all of the staffing, support, and other services necessary to allow an advice-centric advisor to spend as much time as possible actually giving advice to clients. For advisors who operate an on AUM basis, this might mean the broker-dealer advisor platform provides the investment management platform (as well), collects client fees, and remits the advisor’s (70%) share. And in point of fact, there are some advisor platforms that already do exactly this in a non-broker-dealer format, from BAM Alliance to Dynasty Financial Partners and Hightower Advisors.

For firms that support advisors doing retainer and other fees, this may eventually mean broker-dealer advisor platforms offering fee collection solutions for their advisors, again to collect fees from clients, keep their 30% “platform fee”, and then remit the 70% share to their advisors. Alternatively, some broker-dealers may simply establish and assess standalone “platform” fees – which could be basis points, or for non-AUM advisors simply a flat monthly platform fee, which the advisor pays on an ongoing basis to have access to all the technology, tools, and services of the advisor platform. Platforms would then differentiate on the basis of how “turn-key” they are to support certain types of advisors running particular business models or serving certain specialized clientele (the rise of the Turnkey Financial Planning Platform, or TFPP!).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: broker-dealers are facing a form of existential crisis, as the evolution of financial advisors from selling securities products to actually getting paid for advice raises the fundamental question of why it’s necessary at all for an advisor to affiliate with a broker-dealer intermediary to facilitate the distribution of those products. This existential threat to broker-dealers will only be accelerated by the rollout of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, as the potential shift away from upfront commissions – and possibly away from commissions altogether – will open the door to an explosion of non-product-distribution-based advisor support platforms. And while some broker-dealers may be able to make the “shift” from product intermediary to a bona fide advisor support platform, it seems increasingly likely that many simply aren’t positioned to survive (much less thrive) in an advice-centric future.

So what do you think? Will broker-dealers remain relevant in a less-product-centric fiduciary advice future? What services would broker-dealers need to provide to still be appealing as a platform for advisors? Will broker-dealers be disrupted by third-party advisor support platforms from BAM Alliance to Dynasty Financial to XY Planning Network?

How do you see life insurance companies that currently distribute through B/D’s adapting to this? Not necessarily VA’s or other annuities, as that can be structured to pay a yearly fee. I am concerned with actual life insurance sales (whole life, term, UL, etc). I know there is a fee-only life insurance platform (LLIS), but will companies have to restructure all of their products to pay an AUM type of fee? Or do you think these products will have to be sold only in a life insurance agent platform. I doubt the planners are willing to forgo the revenue in cases where life insurance is warranted. I’m not looking to get into a debate of when life insurance is a fit, but it will be interesting to see how the various carriers adapt.

Full Disclosure: I am currently employed by a Life Ins Company.

Chris,

I think there are a few possibilities for this:

1) Some insurance/annuity products might be restructured to pay a trail.

2) Advisors are simply paid standalone advice fees, and the products simply don’t pay at all. (Think doctors: the drug companies don’t pay an upfront commission or a trail – the patient pays the doctor, and the doctor prescribes the appropriate drug)

– Michael

Your analogy, likening annuity/LI product sales by FAs to doctors prescribing medication, has shed some light on potential “corrputing” influence. A pharma company paying a doctor extravagant fees to speak at a conference, or simply to attend, without question, helps to provide incentive to that doctor to prescirbe said pharma compay’s drugs. No, they cannot directly pay trails or commissions to a doctor, but they certainly can dangle a rather large carrot in front of the doctor’s face. Pay-for-play, if you will. I could see the same type of inducement occurring within the finance industry, though there are already similar things going on already; it will only worsen.

Hi,

What sort of compensation model would people recommend for accounts under 25K? Our broker dealer has no program for AUM under that amount. Hence, for people with accounts under 25K we can only make money from front end sales charges. Would the new DoL rule prevent this from happening entirely?

The DOL wants to you to recommend a no-load product to the client. Otherwise you might have to prove that a load fund was in the client’s best interest, and that won’t be easy. The whole idea of the regulation is to reduce the cost of intermediation dramatically. Not only commissions will be affected by the DOL rule. AUM charges could drop to 50 or even 25 basis points.

Where did you get the information that AUM charges could drop to 50 basis points?

At the T3 [Technology Tools for Today] fintech conference in Fort Lauderdale last week, an advisor software builder predicted that in the near future AUM advisors would need four times as many clients to earn as much as they do today. It’s not official, but there’s no reason why AUM managers would be immune to fee compression. I heard the 50 basis point number from an advisor at an FPA conference.

If you are just an investment advisor, I would agree with that point regarding fee compression. They have the most to lose with this new DoL rule and the growth of rob-advisors.

However, if you are a full fledged financial planner who offers soup to nuts services you may be able to justify 1%+ AUM. One just needs to be able to articulate the intangibles of a human advisor. Granted fee compression may still be an issue in the very long run.

I am about to enter the industry after I graduate college in June. I am just very concerned about being able to service young professionals if selling front load commissions is difficult. Hopefully proving that you are working in your clients’ best interest is not much harder than a disclosure form. Luckily, I will be paid to manage my boss’ clients in their small firm in the interim.

Regardless of this new DoL rule and the growth of robo-advisors. I think there is a really large opportunity for young advisors to enter this field.

Load funds will probably not be fiduciary if your commission comes from the manufacturer of the product, instead of directly and transparently from your client. In any case, there’s no solid justification for selling an actively managed fund to a young saver. There’s only tradition, not logic, to tie compensation to AUM. How do you justify charging a $2 million client $20,000 and charging a $1 million client $10,000 for similar services? How do you justify charging a small investor a higher percentage than a HNW investor? The whole arbitrary structure is going to be torn down by the Internet, just as many other retail businesses have already been torn down. The cheese has moved.

One big problem DOL docs in 2005 say NO fiduciary responsibility is owed at all in recommending advice OR in suggesting a Rollover…

A technology provider made a self-serving prediction that you’ll have to rely on his technology to serve more clients than ever just to survive, by plucking numbers out of thin air about where fees may land? Shocking. 🙂

– Michael

A high-end advisor at the same conference told me she had lost three clients to Vanguard’s new personal advisory service in the past year. Sure, there will always be some advisors who can set their own prices. But the trend is definitely toward compression.

Indeed, and I’ve written separately that Vanguard is actually the single greatest competitive threat to independent advisors, not robo-advisors. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/insourced-financial-planning-are-vanguard-and-ria-custodians-the-new-disruptive-threat-to-independent-financial-advisors/

But that’s really not a technology or disruption scenario. That’s simply the competitive reality when a “non-profit” mutual company with $3+ trillion of scale goes head-to-head with for-profit entities that are 1/1000th their size. I’m sure a local farmer with one oil well on his land would get squashed in head-to-head competition with Exxon, too.

– Michael

Mutual insurance company’s have same structure as Vanguard, but you do not see lower product pricing from mutual insurance companies vs. shareholder owned insurance companies. There is an inherent ghost-in-the-machine conflict of interest between a shareholder owned company, like LPL for example, who serves to optimize profits for shareholders while dispensing investment advice, products, and services to investors.

You often see mutual insurance companies price cheaper NET of dividends in the long run. That’s part of their pricing structure and strategy. They price conservatively up front, because if things turn out better, the policyowners just get it back as dividends and a cheaper policy in the future. (Whereas with a stockholder insurance company, if the policy turns out to be conservatively priced, the shareholders win, NOT the policyowners).

Though I’ll grant there aren’t great aggregate statistics to show this, because so few companies are transparent with their pricing (especially on the in-force block of policies). :/

– Michael

I think this is another situation where a

retainer fee structure stands out. The reason the “pay per AUM”

structure falters is that investment management is only a small part of the

service a true financial planner offers. And, in my opinion, is the

easiest to outsource.

The more service the advisor offers for the

retainer fee charged, the more business that advisor wins.

The AUM fee model has been ‘amazingly’ robust so far. I’m not at all convinced that such a drop for comprehensive planning/wealth management services is going to see this kind of drop at all. In fact, if you look at the industry benchmarking studies, AUM fees have gone NOWHERE for years, despite the multi-year rise of robos already. Granted, that doesn’t mean they’ll stay “forever”, but given that robo-advisors have only gotten 0.02% market share, it’s hard to see why their pricing model is the “right” one that all others must succumb to.

More realistically, advisors MARGINS will suffer long before fees go down, as the advisors try to increase their value-add to justify their 1% AUM fee over a lower investment-only robo-advisor baseline. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/why-robo-advisors-may-squeeze-profit-margins-but-shouldnt-cause-advisor-aum-fee-compression-2/

– Michael

As you said in your thorough November article, there are different types of advisors and different types of clients. It’s hard to generalize. There will always be bespoke tailors and people who use them. There just won’t be very many. Your article shows that advisors in general are struggling to hold onto their traditional pricing power. That’s the reality. Advisors are welcome to charge 1% or whatever they want. If consumers are opting for something cheaper–and they are–it doesn’t matter. But let’s be clear: you’re looking at this from the standpoint of the expert advisor, and I’m looking at it from the standpoint of the mass-affluent consumer. Two different perspectives, and two different markets.

The original rationale behind an AUM fee was that the assets were being “managed.” That is, assets were tactically allocated to achieve outperformance. But with a strategic asset allocation approach–which so many RIAs increasingly employ–the rationale for an AUM fee just isn’t there. Consumers will eventually become disenchanted with paying an asset based fee for “planning” and “allocation” recommendations.

I think most advisors will refuse to do business with clients with accounts under 25K. This will be the unintended consequence of the regulation.

Wealthy people need financial consultants, and they always will. But most people are merely retirement savers, and they will need help cobbling together a sustainable retirement income from savings, home equity, Social Security, inheritances, and family support networks. Producers who are being disenfranchised by technology, regulation and commoditization might want to acquire an RICP, RMA or CRC designation and adjust to providing practical advice for $75 to $150 an hour.

The pace of innovation is accelerating with DOL actions as a catalyst, yet the alarm expressed by of the brokerage lobby strawman arguments that oppose the broker’s responsibility to act in their client’s best interest does not bode well for how the industry will fare in a fiduciary world. As Harvards Clayton Christensen counsels, the biggest mistake made by industries when faced with industry redefining innovation is to look at innovation in the context of their existing business model when a new business model is in order. Advisors ask the question of whether massive b/d overhead in OSJ and product bureaucracies add value for the consumer or not? The advisory services infrastructure necessary to support fiduciary duty is more aligned with Robo advisory firms without heavy OSJ and product overhead than broker/dealers. The brokerage business model has a remarkable inability to adapt which will be leathal if professional standing of the broker in advisory services is not advanced based on objective, non-negotiable fiduciary criteria of statute, case law and regulatory opinion letters.

SCW

Why the need for a DOL fiduciary rule, hasn’t FINRA been adequately protecting the interests of the investing public?

Very thoughtful analysis. We are talking with our insurance company clients and looking into new models. It’s interesting to see a different approach from those serving affluent or middle markets.