Executive Summary

In the early days of being a “financial advisor” at a broker-dealer or insurance company, having ’expertise’ meant being well-trained on the company’s products and their features and benefits. ‘Training’ at large financial services firms was primarily focused on product training (and perhaps training in how to sell those products), with the benefit that when the scope of required knowledge is fairly understood – just the features of a handful of the company’s most popular best-selling products – it takes relatively little time to train in the first place. In other words, training up an advisor’s expertise was rather simple and speedy, because the advisor just had to master the inner workings of a few select products.

In the modern era, though, as financial advice is increasingly comprehensive and holistic, the breadth of what it takes to have ‘expertise’ goes far beyond what was required in the product-centric world of 20 years ago. Yet unfortunately, the reality is that the minimum bar to become a “financial advisor” – generally, a Series 6 and 63, 7 and 66, or a Series 65 exam – is largely unchanged through this shift, built around 3 hours of regulatory exams that most can study for and pass in just a few weeks. The end result is that ‘advisors’ are licensed to provide comprehensive financial advice, with no actual requirement to have any training, education, or experience, in personal finance or advice itself.

On the one hand, a voluntary desire to improve financial planning expertise has led to rapid growth of CFP certification in recent years, with more than 5,000 CFP candidates completing the exam process in 2018, up from approximately 3,000 in 2013. Still, though, the total penetration of CFP certification is still less than 86,000 out of approximately 311,000 financial advisors (or barely more than 25%). Which makes it incredibly difficult to deliver financial planning advice efficiently… when the advisor has to research any and every question the client asks, because they lack the depth of expertise to actually know those answers offhand in the first place.

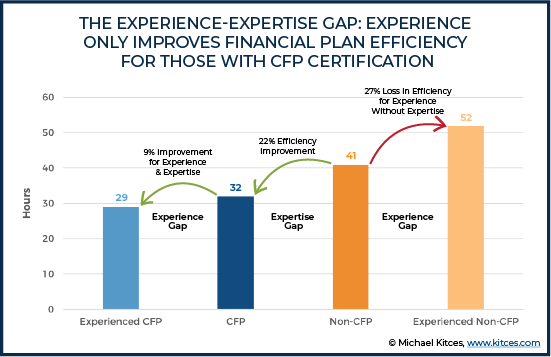

In fact, recent Kitces research on “How Financial Advisors Actually Do Financial Planning” finds an emerging “Experience-Expertise” gap, where having CFP certification reduces the time it takes to complete the first-year financial planning process by 22%, and that amongst the most experienced advisors, having CFP certification reduces the time of the financial planning process by a whopping 44%. As the more experienced the financial advisor, the more confident they tend to be, and the more affluent and complex clientele they tend to attract… which means advisors with more experience actually end out spending even more time to get through the financial planning process (despite the availability of technology, and their years or decades of experience doing it!).

Similarly, more experienced financial advisors also tend to increasingly struggle with the time efficiency of financial planning, because an increasingly complex range of clientele means an ever-widening range of complex situations that the advisor must provide advice on. Notably, though, the real challenge isn’t that more experienced advisors tend to have more sophisticated clientele with more complex needs, but that their needs are differently complex. Which means formulating a niche or more specialized expertise for a particular target clientele can not only be effective for marketing purposes, but also becomes a substantial efficiency improvement, as once the advisor researches and ’learns’ how to handle a particular complex situation, it becomes repeatable expertise for the future as well.

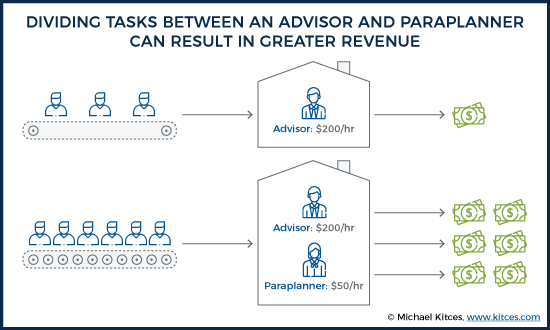

In addition, crafting a more repeatable financial planning process also makes it possible to improve the efficiency of financial planning by leveraging paraplanners who can do not only a portion of the back-office work in financial planning preparation, but even limited-scope portions of the financial planning meeting process as well. Such that, in practice, solo advisors who leverage a paraplanner are able to service an average of 64% more clients and generate 80% more take-home pay by better aligning the tasks being done to the skill and experience (and compensation) level of the team member.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that the majority of the time spent in the financial planning process isn’t actually in the phases of Analyzing and Developing the financial planning recommendations themselves, but also in Establishing the relationship, Gathering data, Presenting the plan, Implementing it, and the ongoing Monitoring process (and the never-ending stream of financial planning questions that crop up from clients along the way). Most of which are human-to-human interactions and communication (either in-person, by video, or via email)… which means the key to improving their efficiency is not necessarily investing in the technology to better automate those processes, but instead investing into the human capital of advisors themselves with deeper and more focused expertise, and a wider range of skill levels to which various financial planning tasks throughout the process can be appropriately (and cost-effectively) matched.

The Experience-Expertise Gap In Delivering Efficient Financial Planning

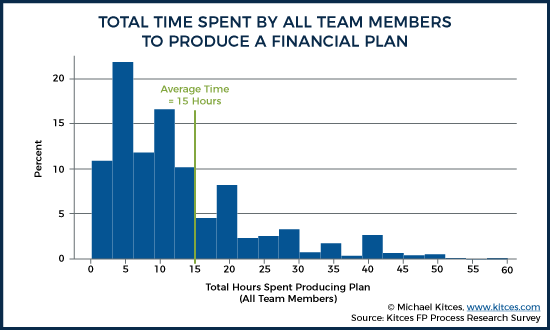

One of the fundamental challenges of creating a comprehensive financial plan is that it takes a lot of time to gather all the requisite financial planning data in the first place, to analyze a client’s full financial situation, to figure out how to craft the appropriate recommendations based on the data provided, and then to present and communicate those recommendations (and implement and support them during the ongoing monitoring phase). Thus, our recent research study on “How Financial Advisors Actually Do Financial Planning” found that it takes an average of nearly 15 hours to create a comprehensive financial plan.

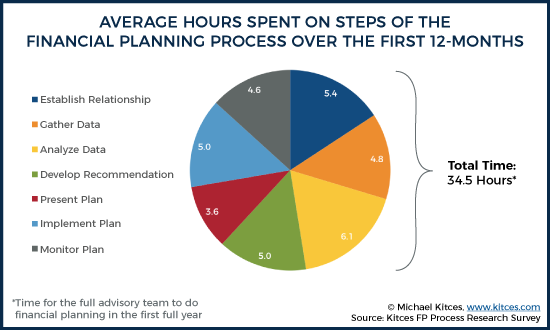

In addition, for advisors providing ongoing financial planning advice, the financial planning process itself doesn’t end at the stage of just ‘delivering’ the financial plan, as there’s still an implementation phase, and subsequent ongoing monitoring required… not to mention all the other new financial planning questions that may arise as the client’s own financial situation changes with time. In fact, our Kitces Research study found that advisors cumulatively spend an average of nearly 35 hours in the financial planning process throughout the first year.

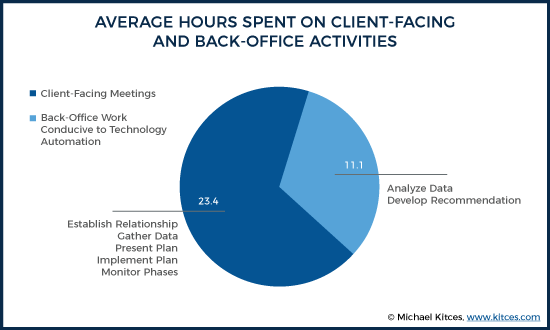

From an efficiency perspective, the fundamental challenge with the financial planning process is that so much of it is client-facing in the first place… a realm that financial planning software can do little to expedite. As while financial planning software might make for a better client experience in the meeting, it still takes a certain amount of time to establish the relationship with the client, engage in a discovery process (of not only the hard financial data, but also the ‘soft’ data gathering of understanding the client’s goals and objectives), and then present financial planning recommendations, implement them, and communicate with clients on an ongoing basis. In fact, the only phases of the 7-step financial planning process that technology is really built to expedite (and potentially automate) are the back-office stages of analyzing and developing recommendations!

Which raises the question: What can be done to improve the expediency of the client-facing portion of the financial planning that constitutes the majority of the actual time spent in the process? The answer: develop greater financial planning knowledge expertise in the first place, with programs like CFP certification.

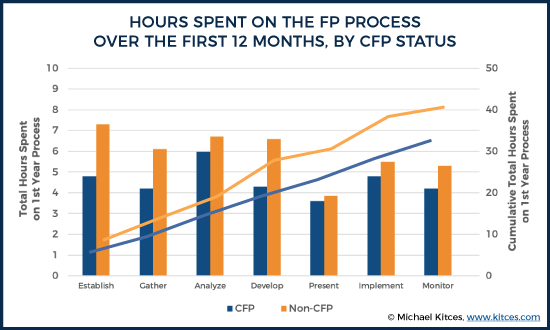

Because as it turns out, the average time to complete the financial planning process for non-CFPs is a whopping 41 hours throughout the first year, while CFP certificants average just 32 hours. In other words, CFP certification effectively leads to a 22% improvement in the time efficiency to deliver financial planning!

And notably, as the chart reveals, the bulk of the time savings for CFP professionals over non-CFPs is not from the ‘create the plan’ phase (i.e., the Analyze and Develop stages, although there is a significant time savings in the time it takes to Develop a plan), but the upfront relationship and data-gathering phase, together with the subsequent implementation and ongoing monitoring phases instead. In other words, CFP certification appears to improve the efficiency by which financial planners ask the right questions up front to establish relationships and gather data, and in how they communicate recommendations and support the client in their ongoing needs… complex conversations where expertise can play a major role.

Of course, in theory any experienced planner who has done enough financial plans with clients can eventually begin to refine the way they ask questions, analyze client situations, and deliver recommendations. As has long been observed in many domains, though, just gaining experience alone isn’t enough. It’s not about how many hours are spent learning a skill, but whether the individual engages in a process of “deliberate practice”, where they don’t just (blindly) repeat a skill to try to learn it, but receive feedback and enhance their knowledge and expertise along the way. In fact, repeated practice of a skill without developing expertise to apply it more effectively can often just result in deeply ingrained bad and inefficient habits.

And as it turns out, that’s exactly what the research shows when it comes to doing financial planning more efficiently. As for non-CFPs, those with more experience actually spend even more time per financial plan in the first year – increasing from an average of 41 hours per year to 52 hours, or a 27% loss in efficiency – while those with CFP certification spend less time per plan as their experience grows (and they obtain the expertise to execute the process more efficiently!), with the average time dropping from 32 hours to just 29 (a 9% improvement).

In other words, when it comes to the financial planning process, there is an “Experience-Expertise” gap that emerges if practitioners gain more experience but don’t match it with a growing base of knowledge expertise.

Accelerating The Financial Planning Process By Narrowing The Scope For Repeatable Expertise

Experience-Expertise gaps emerge over time because financial planners who gain experience, and the confidence to deliver their services, often tend to progress “upmarket” to more affluent clients, who typically have more complex situations. Which are both a better business opportunity and more remunerative for the financial advisor (as there’s more opportunity to deliver value when there’s more financially at stake in the first place). But more affluent clients also tend to be more time-consuming and more burdensome to the experienced advisor, because it means that every client’s situation is both complex and usually substantively different, resulting in a non-trivial amount of research time for each and every new complex client (a problem that is only amplified further if the advisor lacks the expertise of CFP certification in the first place).

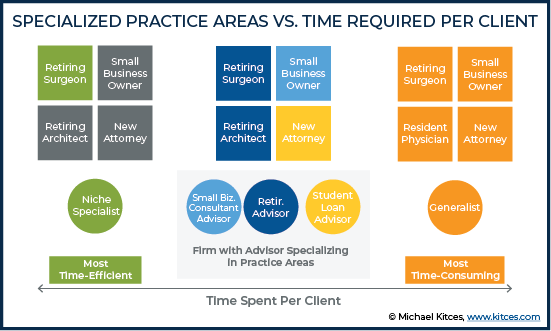

Unless, of course, the advisor tries to develop a more repeatable expertise instead of just developing broader and/or deeper expertise for an increasingly complex and sophisticated clientele. Because in the end, the reason why more complex clients are more time consuming isn’t really a function of the clients being more complex, per se, but because each client is differently complex (necessitating more time in every stage from establishing the relationship and gathering data, to formulating recommendations, implementing them, and fielding ongoing financial planning questions in the monitoring phase).

In other words, one of the key aspects of making the financial planning process more efficient isn’t just developing more expertise (to be able to ask better questions, speed the development of trust, and arrive at recommendations faster)… it’s also about narrowing the range of advice situations by targeting a more focused clientele in the first place, such that even highly complex clients eventually become ‘simple’ because it’s the same complexity from one client to the next, solved with expertise that only needs to be learned once.

In essence, there is a substantial efficiency in the delivery of financial planning by refining towards a particular type of niche clientele. The advisor who specializes in options strategies for tech executives only needs to learn the rules for options once, while the ‘generalist’ advisor (even with CFP certification) will likely need to brush up on the rules when the next client turns out to be the first in years to have options. The advisor who specializes in executives from a particular corporation only needs to learn the company’s executive comp plans once, and then repeatably use that knowledge for each new executive client from that company in the future. The advisor who specializes in student loan strategies eventually masters all the student loan rules, and then has to spend virtually no time at all researching the next ‘complex’ client situation.

An added benefit of developing repeatable expertise is that it also narrows the scope of where the advisor themselves must focus for continuing education. Just as the neurosurgeon keeps up with continuing education on the latest research in brain surgery techniques but not how to do better orthopedic surgery, so too can the niche-based advisor ‘cut to the chase’ on exactly what type of education and professional development is relevant (and just as importantly, what is not).

Notably, for other professional services industries, this type of specialization – including and especially within a larger firm environment – allows the firm in the aggregate to be far more efficient. For instance, it’s common for large law firms or accounting firms to have specialized “Practice Areas” – domains of expertise within the firm – where a group of attorneys or accountants have specialized expertise for people who have that exact type of problem. In the financial planning context, it’s far more efficient for a retirement advisor to get the clients who are retiring professionals, a student loan advisor to get the young professional clients, and an advisor with business consulting expertise to work with those client professionals in the middle (building) stage of their careers, rather than having each advisor work with the full range of each client (necessitating far more research time per client, and more time wasted as the advisor is still figuring out what to ask and what they need to know as they go along the way!).

Similarly, developing repeatable expertise also helps to keep the cost down for the consumer. Thus why most people with a tax problem prefer an accountant who has experience with their specific issue (rather than paying the accountant several hundred dollars per hour to ‘learn’ how to handle the situation). As even though a specialized tax expert may charge a far higher hourly rate for their time, it’s often deemed worthwhile because it’s still less time-consuming (and thus ultimately less costly) than a generalist accountant who is ‘learning on the clock’ (and may still not have as much expertise to solve the problem in the end).

The key point, though, is simply to recognize that developing repeatable expertise to improve the efficiency of delivering financial planning isn’t just about gaining more expertise with CFP certification or additional post-CFP designations… it’s also about better and more narrowly defining the scope of client relationships to ensure that increasingly sophisticated and complex clients are asking repeatably complex questions in the first place! Which allows the advisor to efficiently compound the depth of their knowledge, instead of just inefficiently broadening it!

Leveraging Paraplanners To Improve The Cost Efficiency Of Financial Planning

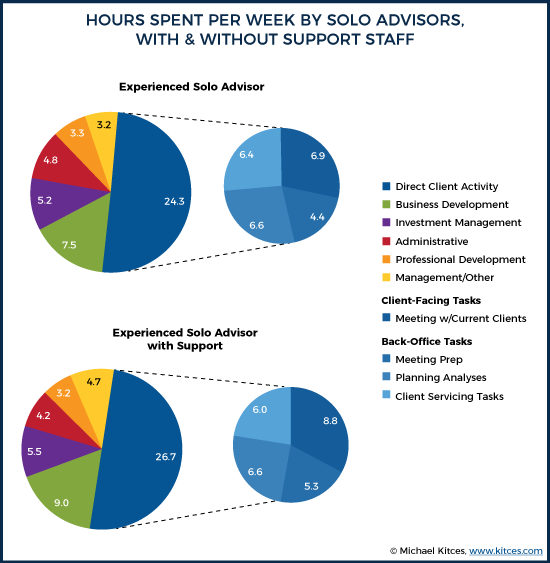

Beyond closing the Experience-Expertise Gap, and developing a more Repeatable Expertise, the third way that the process of financial planning can be made more efficient is by better focusing the lead advisor’s time on the tasks that are truly most necessary and appropriate for him/her to spend time on… and delegating the rest to a paraplanner.

Of course, the model of having an ‘associate’ isn’t unique, and exists in most professions. Accountants and lawyers leverage associates who do a good deal of the behind-the-scenes ‘grinding’ work, which is ultimately supervised and reviewed and then delivered by the senior professional (who spends less time supervising and reviewing than it would have taken to do it themselves, thereby leveraging their time). And the use of associates isn’t unique to just behind-the-scenes tasks. In medicine, nurses and nurse practitioners have, over the years, taken on an increasing number of patient-facing tasks as well – ones that are relatively consistent and repeatable, that can be trained and then easily supervised – leaving the doctor to focus on the most complex aspects of patient diagnosis and treatment.

In the context of financial advisors, our Kitces Research study on “How Financial Advisors Actually Do Financial Planning”found that when an experienced advisor leverages a paraplanner for support, they end out spending almost 4 hours/week (half a business day) more on prospect- (business development) and client-facing activities, which assuming an average meeting time of 1 hour, amounts to more than 200(!) additional client-facing meetings over the span of a year.

Accordingly, the average lead advisor who was operating as a standalone solo advisor (no paraplanner) had an average of 73 ongoing clients, while the average advisor with a paraplanner for support was servicing 120 clients. Which in turn resulted in the average solo advisor generating an average take-home pay of $155k of revenue, while the average lead advisor with a paraplanner was earning $279k (even after paying the paraplanner themselves!).

A key distinction, though, is that paraplanners don’t make the financial planning process more efficient by just analyzing and ‘grinding’ financial plans for clients. Instead, while the plurality of the paraplanner’s time is spent doing planning analyses and meeting preparation tasks, the average paraplanner was still spending an average of 6 hours per week in client meetings supporting a senior advisor, and also took on a substantial burden of client servicing tasks as well (i.e., calls, emails, and other client requests that are routed to the paraplanner instead of to the senior advisor).

In other words, recognizing that the breadth of the entire financial planning process spans beyond just the “analyze and develop” phases of the financial planning process, advisory firms that leverage paraplanners across the entire cycle of the financial planning process, from data gathering and implementation meetings, to the ongoing client service requests in the monitoring phase (in addition to the analyze and develop phases themselves), are ultimately able to service 64% more clients and generate 80% more revenue. Which is more profitable for the business, because a paraplanner does tasks that a paraplanner is able to do at a lower salary than the lead advisor, allowing the advisor to focus their time on activities (generally, prospect- and client-facing) more cost-efficiently.

The key point, here, is recognizing that the time-efficiency of a paraplanner is about more than just delegating (or outsourcing) the time it takes to construct the plan itself (though doing so certainly helps, and there are a growing range of outsourced providers for financial plan ‘prep’ services), but having support across the full range of steps in the planning process. Or viewed from another perspective, the efficiency of a paraplanner is not necessarily about fully delegating ‘small’ clients, but about splitting tasks between the advisor and paraplanner so the paraplanner does a portion of the work for each client (akin to how doctors leverage nurses) in the most cost-effective manner.

With the ongoing rise of technology, “robo-advisors”, and more generally the emergence of robotic process automation across a wide range of industry, there is more and more focus on how software and technology can make the financial planning process more efficient. But in the end, financial planning advice as a business succeeds in large part specifically because it goes beyond what technology alone can accomplish, in a world where most people don’t even really know how to articulate what their goals are in the first place (which makes automated technology tools to calculate how to achieve them a moot point!).

In that context, making financial planning more efficient isn’t necessarily about technology automation at all (which in practice appears to be more about making advisors better than making them faster and more efficient), but instead about how to make non-technology ‘human’ time more efficient instead. Which is where it becomes increasingly necessary to invest into the ‘human capital’ of financial advisors (i.e., closing the Experience-Expertise Gap) in the first place, making human expertise into more repeatable expertise, and leveraging professionals with a wider range of skill levels from ‘associate’ to ‘senior’ advisor to ensure that the necessary tasks are best aligned to the member of the team who will be most efficient at completing them!

Good discussion here Michael. Financial Planning is a funny topic, because there is not a lot of consensus on even what “Financial Planning” includes. Different advisors have different perspectives on what they consider “Planning”. I find that most advisors I know do very basics planning, that is either relegated to basic cash flow/budgeting, or some sort of retirement income projection that ends out in a product recommendation.

Personally, I struggle with what the deliverables should be at times. Ask 5 different planners what they provide for clients, and you get 5 different answers.

And while I tend to agree with what Jeffrey said below about efficiency of delivery (akin to the medical profession), we also have to be careful not to sanitize the process to the point that it becomes painful for the client. Working with a financial planner (beyond investments) can be a deeply personal experience, and I can say from my own experience as a planner that you need to maintain the human connection in the process.

Having said that, I also have a hard time (as Matthew alluded to) visualizing 30-50 hours of work on a single financial plan. Now, maybe this is for a client with a very complex situation (ie. family business, complex real estate holdings, complicated estate planning issues, etc.). But for your “typical” individual, 30+ hours seems excessive.

What I’d love to see is better data on how advisors use their time, specifically data that is independently verified (eg third party observation) and collected in a way the avoids the self-selection bias. Not sure who would pay for this, but one can always dream.

Secondly I’d like to know how much of this self reported 32 hours per plan is actually creating value for the client vs just being entertaining to the advisor.

Ultimately I agree that advisors, like nearly every other profession, must specialize to achieve any kind of efficiency. Otherwise they, like a general practitioner in medicine, will remain the lowest paid and arguable the least valuable to clients.

Michael,

You, IMHO, hit the nail on the head. We need to emulate the medical profession as if functions in a teaching hospital and the legal profession as it functions at the higher levels. I have recently had more experience with medical specialists than would be ideal, but i hve observed that in the local teachig medical center there is a very effecient and effective process. A vocational level worker takes my blood and arranges for the tests. Professional staff, using standardized procedures, produces the resultf for the physician. When I go in to see the specialist physician, I first meet with a nurse who takes my critical information and asks me standardized questions. When I meet with the specialist, he or she already knows the vital data and can ask professional level questions and answer mine. Afther diagnoses, perscription, and direction, a followup date for the next appointment is scheduled by a non-medical staffer.

The result is that the specialist can see a patient every 30 minutes and none of the critical but routine data is missed. The additional result is the specialist can see patients for a far lower fee per patient than we need per financial planning and investment management client and still earn a good wage and keep the institution solvent.