Executive Summary

To limit the otherwise-generous benefits of tax deferral for traditional retirement accounts, the Internal Revenue Code requires retirement account owners to begin taking money out of their accounts upon reaching age 70 ½. Not that retirees are required to actually spend the money. But the funds must be distributed out of the retirement account, triggering income tax consequences, to ensure that Uncle Sam can get his share.

However, the purpose of the RMD rules is simply to ensure that retirement accounts taxation is not deferred any longer than what a reasonable retiree would prudently have withdrawn anyway. As a result, the RMD obligation merely requires that the account owner take money out systematically over his/her life expectancy (or actually, the joint life expectancy of the retiree and his/her designated beneficiary).

To limit potential abuse, though, the Internal Revenue Code and supporting Treasury Regulations prescribe very specific rules about exactly how to calculate what a “prudent” distribution would have been, including when and how to determine the value of the account, what life expectancy to use, the deadline for taking the distribution, and how to coordinate when there are multiple accounts with multiple distribution obligations.

In reality, retirees who are actually using their retirement accounts for retirement spending may well be withdrawing more than enough to satisfy their RMD obligations anyway. However, given the substantial penalties involved for failing to take the full amount of an RMD – a 50% excise tax for any RMD shortfall – it is crucial to ensure that the RMD is calculated correctly (and withdrawn in a timely manner)!

What Is A Required Minimum Distribution (RMD)?

One of the key benefits of retirement accounts, whether in the form of a traditional IRA or an employer retirement plan like a 401(k), is that growth in the account is tax-deferred. Unlike “regular” taxable accounts, where income (i.e., interest and dividends) is taxed annually, and capital gains are taxed upon sale, a traditional retirement account is not taxable until funds are actually withdrawn from the account. Or, in the case of a Roth style account (IRA or 401(k)), the withdrawals may not be taxable at all (if eligible for “qualified distribution” treatment).

The caveat to providing favorable tax treatment for retirement accounts is that ultimately, the Federal government will get its share of the growth. And to ensure this outcome, the Internal Revenue Code requires that eventually, upon reaching a certain age, owners of traditional pre-tax (but not necessarily Roth-style) retirement accounts must begin to take withdrawals from the account – even if they don’t otherwise need the money – and face the tax consequences. The age at which the government says “enough tax deferral!” is 70 ½. And the rules that begin to force money out of the account are called “required minimum distributions” (or “RMDs” for short, and sometimes also known as an MRD instead, based on the IRC Section 4974 penalty for failing to take sufficient “Minimum Required Distributions”).

Because the purpose of the RMD rules is to force the money out of the account, but not necessarily to deplete it at a too-rapid pace (for those who actually need to use the money for retirement spending over the remainder of their lifetimes), the required amount is determined based on the age of the account owner, such that the account “will be distributed… over the life of the [retirement account owner] or the lives of the [retirement account owner] and a designated beneficiary” under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(A)(ii).

In practice, those who are already using their retirement accounts to sustain their retirement lifestyle may already be withdrawing more than enough to satisfy the RMD obligation. Nonetheless, for those who are not actually taking large enough withdrawals from the retirement account, the Required Minimum Distribution, by definition, specifies the minimum required amount that must be taken out, to draw the account down over the remaining life of the account owner. Of course, because it’s only a minimum, it’s always permissible to take out more.

How The RMD Is Calculated

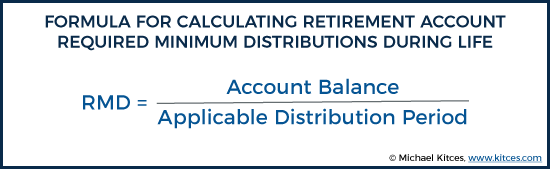

The annual RMD obligation is calculated as a certain percentage of the retirement account(s) that must be withdrawn each year. The percentage itself varies based on the age (and life expectancy) of the retirement account owner. Which means in practice the RMD is calculated as a fraction, where the numerator is the account balance, and the denominator is life expectancy based on the age of the retirement account owner.

However, because the tax code specifies that RMDs must occur “over the life of the retirement account owner, or the lives of the account owner and his/her designated beneficiary”, in reality, Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5 specifies that the account must be distributed not simply over “life expectancy” but over an “applicable distribution period” that considers the prospective life expectancy of both the account owner and the beneficiary.

Determining The Applicable Distribution Period For Life Expectancy RMDs

Historically, the applicable distribution period for retirement account RMDs was determined based on the actual joint life expectancy of the retirement account owner, and the beneficiary associated with that retirement account. Thus, those with younger beneficiaries, who might need the money to last longer (because of the longer life expectancy of a young beneficiary) had smaller RMD obligations.

However, this created substantial complications in practice. Retirement account owners could obtain lower RMD obligations by increasing the denominator of the RMD calculation through the deliberate selection of beneficiaries who were (much) younger and had (much) longer life expectancies… i.e., by choosing children or grandchildren as beneficiaries, instead of a spouse. Yet this also meant that if the retirement account owner unexpectedly passed away, the account would actually go to those beneficiaries, potentially disinheriting the originally intended (e.g., spousal) beneficiary. But naming the intended beneficiary – particularly a surviving spouse – meant naming an older beneficiary (than a child or grandchild), with a shorter life expectancy, causing higher required minimum distributions during life! The end result was an awkward series of trade-off decisions.

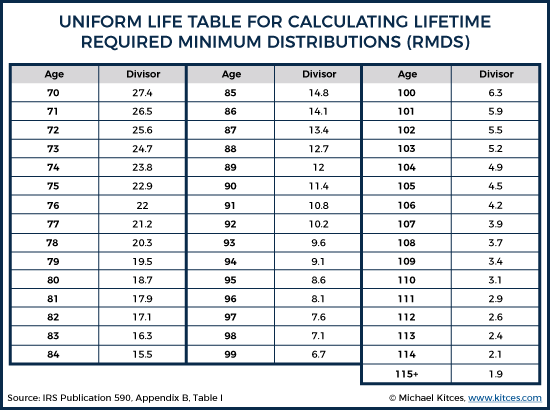

To address these challenges, in 2002 the Treasury issued updated regulations (which first took effect in 2003), drastically simplifying the RMD calculation process. Instead of using the actual joint life expectancy of the retirement account owner and his/her beneficiary (which would vary depending on which beneficiary was named on the account), the rules instead stipulated that the RMD would simply be based on the joint life expectancy of the retirement account owner and a hypothetical beneficiary who is 10 years younger. Thus, the required distribution for a 71-year-old would be based on the joint life expectancy of a 71-year-old and a 61-year-old. An RMD for a 77-year-old would be based on the joint life expectancy of a 77-year-old and a 67-year-old. Etc. Regardless of the actual age of the named beneficiary.

These Applicable Distribution Periods – based on the joint life expectancy of the account owner and a 10-years-younger beneficiary – were then codified in what is now known as the “Uniform Life Table” (uniform, because it applies to all retirement account owners regardless of who the actual beneficiary is), available in Table III of Appendix B of IRS Publication 590.

RMDs With Spouse Vs Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

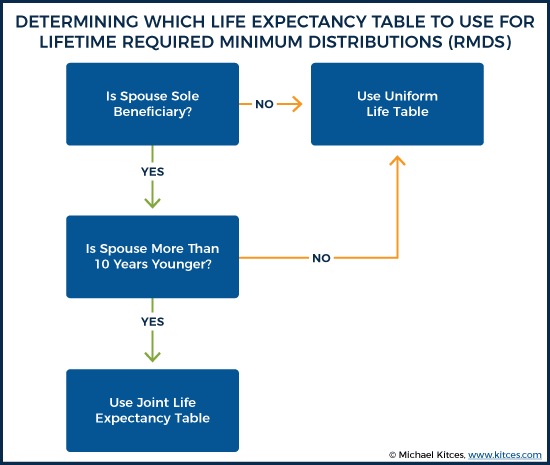

As noted above, the standard rule for RMDs is that all RMDs are calculated based on the age of the retirement account owner, using the Uniform Life Table – which is automatically based on the joint life expectancy of the account owner, and a hypothetical beneficiary who is 10 years younger (regardless of the actual age of the beneficiary).

The only exception to the standard rule of using the Uniform Life Table, under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A-4(b), is that in situations where a spouse is the sole beneficiary of the retirement account, and the spouse is more than 10 years younger than the account owner, the RMD may be calculated using the actual joint life expectancy of the account owner and his/her spouse (with the appropriate age-specific joint life expectancy tables provided in Table II of Appendix B of IRS Publication 590).

In order for the spouse to be treated as the sole beneficiary of the retirement account, he/she must be the sole beneficiary for the entire calendar year. (However, in the event of a change in marital status, Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-4(b)(2) stipulates that as long as the retirement account owner was married on January 1st of that year, the spouse can be treated as the [sole] beneficiary, even if the couple divorced or the spouse died later in that year.) Notably, this means that if an IRA has multiple beneficiaries including a spouse, it will not be eligible for the favorable treatment; instead, the IRA must be split, with the spouse as sole beneficiary of his/her share, for that IRA to be eligible for the more favorable joint life expectancy table.

In situations where there is a sole spouse as the beneficiary who is more-than-10-years younger, it will always be advantageous to use the joint life expectancy table. As the joint life expectancy with a more-than-10-years-younger spouse will be even longer than the Uniform Life table, which increases the denominator of the RMD calculation, and results in a smaller RMD obligation, effectively minimizing the size of the RMD.

Thus, ultimately, the applicable distribution period will either be the Uniform Life table (the joint life expectancy of the account owner and a hypothetical beneficiary who is less than 10 years younger), or the Joint Life table with the actual joint life expectancy of the account owner and his/her spouse, if the spouse is the sole beneficiary and more than 10 years younger.

Determining The Correct Age To Use For RMD Calculations

When determining the correct “age” to use in referencing the life expectancy tables, the Regulations require that calculation be based on the age of the individual at the end of the current distribution year – i.e., how old he/she will turn on his/her birthday this year.

Example 2. Ashley is currently age 72, and will turn 73 in November. As a result, Ashley’s RMD for the current year will be based on her age 73, even though he/she is 72 for “most” of the year. In fact, even if Ashley takes her RMD early in the year – when she’s still actually age 72 – her RMD will still be calculated using age 73, based on how old she will be on her birthday (and at the end of the year).

In the case of a more-than-10-years-younger sole spouse beneficiary, the age of the spouse for the purposes of the joint life expectancy table is also determined as of the end of the current year (i.e., again based on the age he/she will attain on his/her birthday in the current year).

Notably, for the first RMD – due for the year in which the individual turns age 70 ½ – the first applicable distribution period may be based on either age 70, or age 71, depending on when the individual’s birthday falls during the year. Those whose birthdays fall in the first half of the year will calculate their first RMD based on age 70, as they will not yet have turned age 71 by the end of the year. However, those whose 70th birthdays fall in the second half of the year will not turn 70 ½ until next year, which is also the year they turn age 71; as a result, those individuals will never actually take an RMD based on being age 70, as their very first RMD will already use the age 71 life expectancy factor.

Example 3. Neil was born on August 22nd of 1947, and has a $150,000 IRA where his son Jonathan is the beneficiary. As a result, Neil turns 70 on August 22nd of 2017, which means he will turn age 70 ½ on February 22nd of 2018, and 2018 will be his first required minimum distribution year. Given that 2018 is Neil’s first distribution year, and he will turn 71 that year (on August 22nd), his first RMD will be based on the age 71 life expectancy factor in the Uniform Lifetime Table. As a result, Neil will divide his 12/31/2017 account balance by 26.5 to determine his first RMD for 2018, and he will never actually use the age-70 applicable distribution period of 27.4.

Determining The “Value” Of The Retirement Account For RMD Purposes

To calculate a required minimum distribution, it’s necessary to divide the value of the account by the applicable distribution period. In most cases, the “complexity” of an RMD is determining the right applicable distribution period, using the appropriate life expectancy table. In some cases, though, determining the account value presents challenges as well.

The standard rule under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-3, is that the account is valued based on “the account balance” at the end of the prior calendar year. Thus, for instance, if the individual’s first required minimum distribution is due for the 2017 calendar year, the valuation date is December 31st of 2016.

For most investments, this approach to determining the account balance is relatively straightforward, and simply involves either obtaining a prior-year 12/31 statement (showing the account balance), or reporting the account balance obtained from the advisor’s portfolio accounting and performance reporting engine.

However, additional complexities arise in the case of illiquid securities, which in the extreme may require obtaining a standalone valuation to determine the RMD (particularly in the case of self-directed IRAs directly holding illiquid alternative assets). The fact that an asset may be hard-to-value doesn’t excuse the requirement that it must carry some reasonable value for RMD purposes.

Another complexity that arises in determining the “value” to use for RMD purposes is in the case of substantial bond holdings, which may have accrued interest, and particularly directly-held TIPS bonds, which also periodically accrue a principal adjustment for inflation. Unfortunately, the Internal Revenue Code and Treasury Regulations themselves are actually silent on the issue of whether/how accrued-but-unpaid bond interest (or periodic TIPS principal inflation adjustments) should be considered for the purposes of determining the “account balance” of a retirement account for RMD calculation purposes.

Notably, though, the plain reading of Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-3 itself, states that the amount used to determine the RMD is the “account balance”, and does not explicitly stipulate that the “fair market value” must be used, as is required for other valuation purposes (e.g., the value for gift or estate tax reporting). Of course, even an “account balance” must still itself be valued, but Treasury Regulation 1.1471-5(b)(4) states that “the balance or value of a financial account is the balance or value calculated by the financial institution for purposes of reporting to the account holder.” In other words, whatever the standard practice is for the financial institution in reporting the “value” of the assets held in the account (and whether the institution reports accrued bond interest as part of the valuation) really does become the “proper” valuation to be used for RMD reporting purposes.

Nonetheless, given that the going price of a bond in the open market really does reflect the amount of its associated accrued interest, most advisors err to the side of caution and calculate all required minimum distributions including accrued bond interest. And in point of fact, many financial institutions typical report the value of the account including accrued bond interest anyway.

Fortunately, in practice the difference is often not very material, particularly in today’s low-interest-rate environment. Even a $100,000 bond paying a 1.5% coupon twice a year (for a 3% annual yield), with a payment date that happens to fall just after New Year’s (such that the 12/31 value would include virtually all of the prior 6 months’ worth of accrued-but-still-unpaid interest), would only have to increase the first RMD by $54 to account for the accrued interest.

RMD Valuations For Deferred Annuities With Guaranteed Benefit Riders

While the general rule for calculating an RMD for a retirement account is that it’s based on the “account balance” from December 31st of the prior year, special rules apply when determining the value of a deferred annuity held inside of a retirement account.

The reason is that in today’s world of deferred annuities with potentially significant death benefit or living benefit riders, “just” looking at the account balance alone may substantially understate the true value of the contract, to the point of distorting tax outcomes.

For instance, if an annuity contract has a current cash value of $100,000, and a death benefit rider that is locked in at $300,000, is it really fair to say the value of the contract is “just” $100,000 for RMD purposes, when it may someday soon pay out another $200,000 in extra death benefits? Or in the extreme, where some annuity contracts allow withdrawals to reduce guarantees on a dollar-for-dollar basis, what if the owner of the aforementioned annuity withdrew $99,000, leaving a contract behind with a $1,000 cash value, and a $201,000 death benefit? Is it really appropriate to view the contract as being worth “just” $1,000, especially if the annuity owner is very old, such that the $1,000 will likely turn into that $201,000 death benefit sooner rather than later?

To close the potential loophole, in 2005 the Treasury issued Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-6, Q&A-12, which stipulated that in the case of a deferred annuity inside of an IRA, the determination of the RMD must be based on the “entire interest” under the annuity contract, which includes both the account balance, and the “actuarial present value” of additional benefits and guarantees. Thus, for instance, if an annuity had a $100,000 cash value but a $300,000 death benefit, then the value of the annuity would be $100,000 of cash plus the actuarial value of the extra $200,000 death benefit based on the annuity owner’s age (in essence, $100,000 plus the cost of $200,000 term insurance for that year for someone of comparable age).

To at least partially simplify the process, though, the Treasury Regulations do state that the calculation of the actuarial present value of additional benefits can be done using “reasonable” actuarial assumptions, but without regard to the individual’s health; thus, there’s no requirement to individually underwrite the economic value of any benefit guarantees (based on that person’s specific health circumstances), but simply to evaluate the likely prospective value based on the individual’s age, and the cash value and level of death benefit (or living benefit) guarantees.

In addition, the Regulations state that the actuarial present value of additional benefits can still be ignored if either:

a) The additional benefits add no more than 20% to the value of the contract, where any future withdrawals reduce benefits on a pro-rata basis and the death benefit guarantee is only a return-of-principal guarantee; or

b) The only additional benefit is a return-of-principal death benefit guarantee (in which case the actuarial present value can be ignored, regardless of how much additional value it provides)

Notably, these exceptions still mean that any “old” annuity contracts that provide living benefit riders that allow for dollar-for-dollar withdrawals, or any annuity contracts that have “enhanced” death benefit guarantees (beyond just a return of principal guarantee), are not eligible for the exceptions and must include the actuarial present value of the additional benefits. In addition, even living benefit riders that allow for pro-rata distributions must still be considered in the valuation for RMD purposes if their value is “substantial” (and would increase the RMD valuation by more than 20% of the total account value).

In extreme cases, it’s important to note that the RMD obligation could conceivably even exceed the entire cash value of the annuity, in scenarios where the contract is almost depleted, but the remaining guarantees are substantial – for instance, in a situation where ongoing withdrawals have reduced the annuity contract’s cash value down to $1,000, but there is still a large death benefit or living benefit rider remaining that’s worth far more. Fortunately, in situations where the contract is depleting but a living benefit rider remains, there is often an option in the contract to effectively “annuitize” into guaranteed lifetime income, which relies on different RMD rules for annuitization. In addition, as discussed below, because RMDs for an IRA can be satisfied from any IRA under the RMD aggregation rule, it may be feasible to simply draw the required amount (after considering the actuarial present value of additional benefits) from another retirement account. Nonetheless, in the case of a contract that just has a large death benefit guarantee, where distributions are ongoing or at least planned, it is important to plan in advance for a potential draw-down. Though fortunately, because the value of term insurance is only a small percentage of the death benefit, and the RMD obligation is only a percentage of that, the risk is unlikely.

In practice, though, the biggest complication in determining RMDs for qualified annuities with substantial additional benefits is simply determining the appropriate “actuarial present value” of the additional benefits in the first place. In most cases, annuity companies will provide a reasonable estimate, but some do not, and others do not provide very “sophisticated” or accurate valuations. (Retirees and their advisors can seek out third-party actuaries for a third-party valuation if necessary, where the prospective size of the RMD and the tax consequences are large enough to merit paying for an independent valuation.)

Adjusting The RMD Account Balance For (Subsequent) Rollovers And Recharacterizations

In most cases, determining the account balance of a retirement account at the end of the prior year is relatively straightforward – simply pull out the year-end statement and see what the value is. Even if retirement accounts are being transferred from one plan administrator or IRA custodian to another, by the end of the year, the money will be in one account or another, with the “old” account reduced by the value of the transfer out, and the “new” account increased by the amount that transferred in.

However, in some scenarios, the transfer may actually be in “mid-course” at the moment the year ends, especially in situations where funds weren’t (or couldn’t be) transferred as a trustee-to-trustee transfer, and instead were conducted as an actual “rollover” – where the account balance is distributed to the account owner, who individually takes possession of the money, deposits it into a checking or brokerage account, and then “rolls over” the funds within 60 days (after the start of the new year).

Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-7 for employer retirement plans, and the associated Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-7 for IRAs, provides guidance on how to handle such situations. Where transfers are still underway at year end, the “distributing plan/account” – the source that the transfer was taken from – simply uses its year-end account balance, reduced as applicable by the amount that was already distributed/transferred by year end. However, the receiving account, where the funds are rolled in, must have its year-end account balance retroactively adjusted and increased by the value of the assets rolled in. Thus, even if the roll-in finishes in the following calendar year, it is still treated as being associated with the new account as part of its prior-year account balance associated with the year the money was originally distributed (to ensure that retirees don’t “vanish” portions of their retirement accounts with year-end rollovers just to avoid or minimize RMDs!).

Example 4. Jeremy is 72 and has a $300,000 401(k), and decides to transfer $100,000 of the account to an existing IRA worth $500,000, that has more appealing investment opportunities. The 401(k) plan administrator cannot facilitate a trustee-to-trustee transfer, and as a result distributes a $100,000 check to Jeremy on December 22nd of 2016. Jeremy deposits the $100,000 check into his checking account, and completes the rollover by depositing the funds into the existing IRA on January 7th of 2017.

As a result of this rollover, Jeremy’s 401(k) account finishes with a $200,000 account balance (the original $300,000 balance, less the $100,000 distribution) at the end of 2016, and Jeremy will be obligated to take an RMD from the 401(k) plan in 2017 based on the $200,000 balance. However, Jeremy’s 2017 RMD for his IRA will be calculated based on a $600,000 account balance, including the $500,000 year-end balance at the end of 2016, plus the $100,000 that was contributed in 2017 but came out during the 2016 tax year (and thus is still attributable to the 12/31/2016 account balance for RMD purposes).

Notably, in the event of a Roth conversion with a subsequent recharacterization, Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-8(b) also requires that the recharacterization amount be added back to the end-of-prior-year account balance to determine the appropriate RMD. The end result is akin to the scenario where an IRA rollover completes after the end of the year; the amount that was recharacterized must still be considered for RMD purposes, and holding an amount in Roth-conversion-and-recharacterization-limbo does not allow RMDs to be avoided. Including any subsequent growth that might have happened during the transition period.

Example 5. Charlie is 73 years old, and did a partial Roth conversion of $125,000 of his $400,000 IRA to a Roth at the end of last year. Immediately after the conversion, his IRA was worth only $275,000. However, Charlie discovers as he prepares his tax return, that he converted so much that he drove his tax bracket up to the 28% rate, and had only wanted to fill the 25% tax bracket. As a result, he recharacterizes $28,000 of his conversion, which, due to interim growth, requires actually recharacterizing $29,000 of assets back to his IRA.

The end result is that Charlie must still report $97,000 of his Roth conversion as income (the $125,000 original conversion, reduced by the $28,000 recharacterization), but for RMD purposes, his prior-year-end balance is $275,000 + $29,000 (the actual amount recharacterized, including growth) = $304,000. Notably, this actually puts Charlie in a slightly worse position than he would have been in by just not converting that $28,000 in the first place – as the growth after the end of the year must be added back to his RMD calculation from the prior year-end. However, the difference is fairly minimal in impact, as Charlie’s RMD at age 73 is only 4.05% of his account balance, resulting in an extra $40.50 of RMDs on the $1,000 growth difference, and $10.13 of additional taxes (at a 25% tax rate).

It’s important to bear in mind that because a Roth recharacterization can occur as late as October 15th of the year after the Roth conversion, it could be well into the current year before a late-year recharacterization retroactively impacts the prior-year-end account balance for calculating the current year’s RMD. As a result, while it’s prudent to calculate RMDs at the beginning of the year, to ensure that all affected retirement account owners know the amount that needs to be taken, it’s important to revisit RMDs for all clients towards the end of the year – after all prior-year rollovers and any Roth recharacterizations have been completed – to ensure that the amount of the RMD didn’t change after the fact! Especially since a Roth recharacterization that occurs in October means the account owner only has 3 more months in the current year to (re-)calculate and then take any remaining RMDs that might now be due given the retroactive adjustment to the RMD calculation.

Multiple Retirement Accounts And The RMD Aggregation Rule For IRAs

When there are multiple retirement accounts, each account will have its own RMD calculation, and the RMD must be taken from that account to satisfy the RMD obligation for that account. Thus, in the case of employer retirement plans, such as 401(k) and profit-sharing plans, etc., the RMD for that account must then be taken from that particular account.

However, in the case of IRAs, a simpler RMD aggregation process applies for satisfying RMD obligations across multiple accounts.

Specifically, under Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-9, any distribution from any IRA can be used to satisfy the RMD obligation for all of that individual’s IRAs. In other words, once the RMD amount is calculated for each IRA separately, the amounts are then totaled up, and the only requirement is that the total amount must cumulatively be withdrawn from any IRAs to satisfy that year’s RMD obligation for all IRAs.

Example 6. Christopher is turning 73 years old this year, and has two IRAs. The first, worth $500,000, has his 61-year-old wife named as the sole beneficiary. The second, worth $100,000, has named his 37-year-old son as the beneficiary.

For the first account, where the sole beneficiary is a more-than-10-years-younger spouse, the joint life expectancy factor is 26.1, resulting in an RMD of $500,000 / 26.1 = $19,157.09. The second account, however, will use the Uniform Life Table (given a non-spousal beneficiary), and thus uses a life expectancy factor of 24.7, resulting in an RMD of $4,048.58.

As a result, Christopher’s total RMD obligations for the year are $19,157.09 + $4,048.58 = $23,205.67. And ultimately, Christopher can take that $23,205.67 from any of his IRAs to satisfy his RMD, regardless of which account the calculation was originally associated with.

Notably, the RMD aggregation process applies only to IRAs (including SEP and SIMPLE IRAs), and does not aggregate in other employer retirement plans like 401(k)s or profit-sharing plans). Although 403(b) plans are also eligible for aggregation, but only with other 403(b) plans.

In addition, the RMD aggregation rule applies only to that individual’s own IRAs or 403(b)s (thus, for instance, the RMDs of a husband and wife’s separate IRAs are not aggregated, and each must take their respective RMDs from their own respective IRAs). Furthermore, the RMDs from any inherited IRAs are not aggregated with the RMDs from his/her own IRAs, nor are inherited IRAs aggregated with each other (although all inherited IRAs for a single beneficiary and from a single decedent may be aggregated for calculated that inherited RMD). And since Roth IRAs have no lifetime RMD obligations at all, Roth accounts (and distributions from Roth accounts) are not aggregated with nor used towards satisfying the RMDs for non-Roth traditional retirement accounts.

Notably, to the extent that a distribution is partially non-taxable (i.e., as a return of previous non-deductible/after-tax contributions to the retirement account), the full amount of the distribution (both taxable and non-taxable portions) still count towards satisfying the RMD, under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-9.

RMD Reporting Rules For IRA Custodians

Fortunately, since 2003, under Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-10, the custodian or trustee of an IRA is required to report to the account owner that an RMD is due for the current year and provide an offer to calculate the RMD amount, or alternatively can just outright provide the account owner a calculation of the amount of the annual RMD obligation from that IRA. In either case, the RMD notification must also show the due date for that RMD (which will generally be December 31st of the current year, except in the case of the first RMD that is due by April 1st of the following year). The notification of this RMD due date and calculation itself must be provided by January 31st of that year, for the RMD that will be due that year.

Thus, as long as the IRA owner is alive at the beginning of 2018, the IRA custodian will be required to provide a calculation of the RMD to that IRA owner by January 31st of 2018, based on the account balance on December 31st of 2017, and how old the IRA owner will be on December 31st of 2018.

In addition, beginning in 2004, IRS Notice 2002-27 also requires that the IRS custodian report directly to the IRS on Form 5498 whether there is an RMD obligation for the account, by checking Box 11 of that form (if an RMD is due for that tax year). Reporting the actual amount of the RMD obligation on Form 5498 is optional. However, since 2009, IRA custodians have had the choice to report the RMD due date and amounts in boxes 12a and 12b of Form 5498, and if the Form 5498 is sent with those boxes completed by the January 31st deadline, the Form 5498 itself can satisfy the IRA custodian’s reporting requirements to the IRA owner as well.

Notably, though, when reporting the calculated amount for an RMD, the IRA custodian is permitted to assume that the beneficiary is not a more-than-10-years-younger spouse, and rely solely on the Uniform Life Table. As a result, if the (sole) beneficiary of the IRA actually is a more-than-10-years-younger spouse, the RMD calculation will overstate the actual RMD obligation.

However, since the RMD notification is purely for informational purposes (both to the individual, and to the IRS), the IRA owner is permitted to take the smaller and more favorable required minimum distribution amount based on the joint life expectancy table (where permitted), notwithstanding that the IRA custodian’s reported amount was higher (based on the Uniform Life table). Similarly, even though the IRA custodian provides a report of the calculated amount of the RMD, there is no requirement that the RMD be taken from that particular account, per the RMD aggregation rule for RIAs.

In any event, though, no reporting of the RMD obligation (on Form 5498 or to the IRA owner directly) is required for inherited IRAs; only for lifetime RMD obligations for the original (still-alive) IRA account owner. In addition, there are no reporting requirements for RMD obligations from defined contribution employer retirement plans (e.g., 401(k) or 403(b) plans, profit-sharing plans, etc.).

Consequences Of A Missed Distribution Or Incorrect RMD Calculation

Under IRC Section 4974, the failure to take the full amount of a required minimum distribution (whether as an outright distribution, or via a Qualified Charitable Distribution) results in an excise penalty tax equal to 50% of the RMD shortfall amount. Notably, though, the penalty is only for the shortfall amount of the RMD, not the entire RMD obligation.

Example 8. Henry had a total RMD obligation this year of $8,000, but he only took $3,000 of distributions this year. As a result, Henry will face the penalty tax for failing to take his full RMD, and the penalty would be equal to $5,000 (RMD shortfall) x 50% = $2,500. If Henry had missed his entire RMD, the penalty would be $8,000 x 50% = $4,000.

In addition to owning the 50% penalty tax for failing to take an RMD, the IRA owner must still actually take the full and proper RMD amount as well – once the error is discovered – and incur any income taxes that are due when the proper distribution actually occurs. (Notably, this rule applies to both RMD obligations during life, and the consequences for missing a post-death RMD obligation under the so-called "Stretch IRA" rules.)

A failure to take an RMD, and the associated penalty, is reported on IRS Form 5329 – which can also be used to request a waiver of the RMD penalty.

So what do you think? Do you have a process for ensuring that proper RMDs are being taken? Have you ever run into cases where the calculated RMD is different than the client's actual RMD? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!