Executive Summary

The conventional view of sequence-of-return risk is that it’s something retirees face as they take ongoing distributions from a retirement portfolio, and requires caution in the early years of retirement.

Yet the reality is that sequence of return risk is equally relevant for accumulators in the years leading up to retirement as well. The only difference is the problematic sequence is reversed – for retirees, the dangerous sequence is to get bad returns at the beginning (of retirement), while for accumulators it’s getting bad returns at the end (of the accumulation phase) that causes the problem.

In fact, the volatility of an accumulator’s portfolio can also be viewed as its “retirement date risk” – the danger that a planned date of retirement (or financial independence) may turn out to be later than originally expected, due to a poorly timed sequence of bad market returns. And as it turns out, the greater the volatility of the portfolio and reliance on growth, the greater the retirement date risk that goes along with it.

Accordingly, accumulators in the final years leading up to retirement may wish to proactively manage risk and reduce the volatility of the portfolio, specifically as a means to reduce the retirement date risk they face. Of course, getting a portfolio more conservative at the end of the accumulation phase may also force an accumulator to work slightly longer, or save more, to make up for the lower expected returns in those last few years. Still, for those who don’t want the risk of a much later retirement date, a decreasing equity glidepath leading up to retirement may be a very appealing retirement date risk management strategy!

Sequence Of Returns Risk For An Accumulator

A fundamental challenge for retirees taking ongoing withdrawals from a portfolio is “sequence of returns” risk – the fact that even if markets average out to long-term returns eventually, if early returns are too low for too long, ongoing withdrawals can deplete the portfolio before the “good” returns finally arrive. Notably, this issue does not apply if the portfolio has no withdrawals, such that all the dollars which experience a decline can participate in the subsequent recovery. Sequence of return risk is limited to situations where there are ongoing cash flow distributions coming out of the portfolio.

Except as it turns out, sequence of return risk is not unique solely to retirees taking money out of a portfolio. It also applies to accumulators who are still making contributions into a portfolio a well.

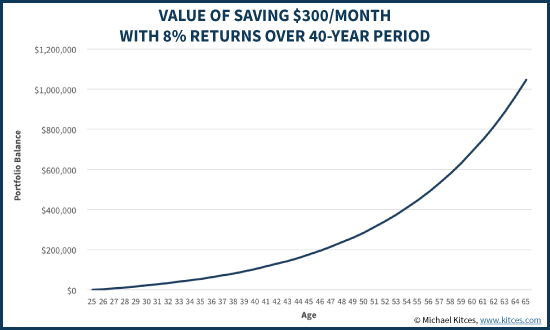

For instance, imagine an investor whose goal is to accumulate $1,000,000 by saving $300/month every month starting at age 25. Assuming an 8% long-term rate of return on a balanced 60/40 portfolio, this systematic savings strategy would be able to accumulate a $1,000,000 portfolio balance by age 65, after 40 years of compound savings.

The caveat, however, is that the projected accumulation above doesn’t just assume the portfolio gets a long-term average return of 8%, but that it generates a return of exactly 8% every year. And just as any deviations from that return assumption can dramatically impact the sustainability of retirement distributions from a portfolio (sequence of return risk), so too can it adversely impact the projected accumulation of a retirement portfolio with ongoing contributions, too.

For instance, a 60/40 portfolio has a long-term standard deviation of about 12% per year, or about 3.8% per decade (the standard deviation declines by the square root of the number of years). Given that 95% of returns are expected to fall within plus-or-minus 2 standard deviations, this means that an average return of 8% would actually have a 95% chance in any decade of falling somewhere between 0.4% and 15.6% (per year compounded across the 10 year time window).

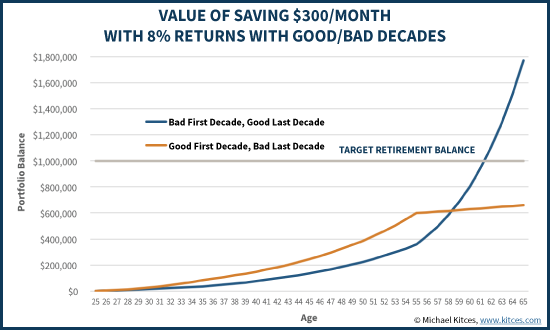

So what happens if, for our earlier accumulator, the first decade experiences a bad -2 standard deviation event, but the last decade (right before retirement) recovers with a +2 standard deviation bull market? Or conversely, what if the favorable bull market happens at the beginning, and the -2 standard deviation mediocre decade comes at the end. (Notably, these would not be “black swan” events, but merely a known-to-be-possible bad decade of returns.)

As the results reveal, the sequence of returns has a dramatic impact. In both of the above scenarios, the long-term returns are exactly the same. Both accumulators averaged out to the same long-term returns of 8%. The difference is simply that one had good returns early on (when few contributions had yet been made to the portfolio), and then had bad market returns later that impacted the bulk of the savings. The other had bad returns early on (with not much in savings to be impacted), and enjoyed the good returns at the end when most of the contributions had already been made.

For someone working towards retirement, the difference is significant. In the good sequence, the accumulator with the “plan” to retire at 65 with $1,000,000 actually reaches the goal by age 62. On the other hand, the accumulator with the bad returns is still 34% short of the $1,000,000 goal at age 65, and even if returns subsequently revert back to 8% that accumulator will still have to wait until age 70 to actually reach the original $1,000,000 goal!

There is a significant risk that their actual retirement date will be materially different than the goal that was set in the first place, as the age 65 retirement date goal ends out with an 8-year time window in which it may fall! (And of course, a severe bear market in just the final year or two before retirement could make the situation even worse!)

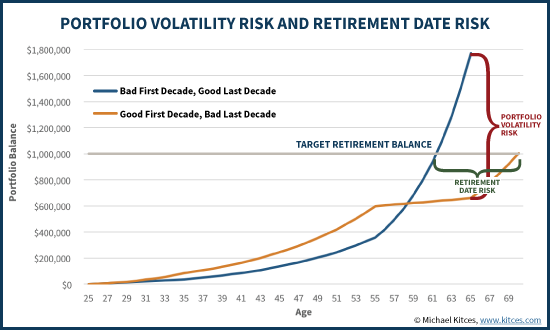

How Portfolio Volatility Causes Retirement Date Risk

Portfolio volatility is typically used to characterize the ways a portfolio’s value can go up and down from year to year. But in the context of an accumulator saving for retirement and facing sequence of return risk, volatility doesn’t just impact the value of the portfolio, per se, but the timing of retirement itself. Or viewed another way, portfolio volatility for an accumulator creates retirement date risk.

The reason that portfolio volatility causes retirement date risk is that the goal of retirement typically has two components: a target dollar amount (to cover retirement spending), and a target date by which that amount will be accumulated (so the accumulator can stop working!). This joint goal means that if the accumulator can’t achieve one part, the other must be adjusted.

In the context of an accumulator who is forced to retire early – e.g., due to an adverse health event – the retirement date becomes unchangeable, and thus spending must be adjusted (often downwards) to accommodate the retirement transition.

For those who can continue working, though – until they choose to retire – the path is typically to keep working until the retirement accumulation goal is achieved.

Yet this means that a volatile portfolio with an ill-timed bear market or poor results can end out forcing the accumulator to work longer, waiting until the portfolio recovers! And the greater the reliance on growth, the more sensitive the outcome is to the volatility of the portfolio (the greater the potential for a shortfall on the originally-intended retirement date), and thus the greater the retirement date risk!

How To Manage Retirement Date Risk

So how can a prospective retiree manage their exposure to retirement date risk?

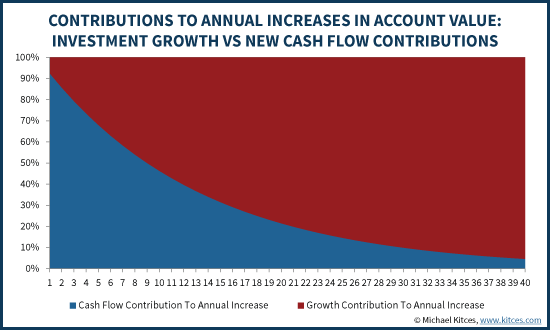

The first key is to recognize that for the final decade leading up to retirement, it’s primarily the volatility of the portfolio and its returns that matter; the ongoing savings contributions are no longer the driver of the outcome. The reason, simply put, is that as a portfolio compounds, the relative impact of contributions themselves are less and less.

For instance, in the first year, adding $300/month (or $3,600/year) takes the account balance from $0 to $3,600! In the second year, if the portfolio earns its expected 8%, the growth is only $288 while new contributions are another $3,600 – a year’s worth of growth is less than one month’s contribution!

By the last decade, however, the tables turn. In the final years, return on the investment portfolio dominates its increases in value, and new contributions become trivialized. Over the very last year, as the portfolio grows from nearly $925,000 up to the final $1,000,000 target amount, growth contributes almost $75,000 to reach the finish line, dwarfing the $3,600 of new (final-year) contributions. In fact, while in the second year one year’s worth of growth is the same as just one month’s contribution, in the final year one month’s growth is nearly double one year’s worth of savings!

Accordingly, the reality is that managing retirement date risk really is all about managing the volatility of the portfolio itself, and not necessarily the contributions to it (except to the extent that a lower volatility portfolio with a lower growth rate may require larger contributions to meet the retirement goal in the first place).

A Decreasing Equity Glidepath Into Retirement (Using Lifecycle Funds?)

Since the driver of retirement date risk is the volatility of the portfolio, the easiest way to reduce retirement date risk in the final years is to reduce portfolio volatility itself in those final years. What this means in practice is that retirement date risk can be reduced by decreasing exposure to volatile assets (e.g., equities) in the final years leading up to that target retirement date.

In this context, the reality is that target date funds (or lifecycle funds), which typically take equity exposure off the table in the years leading up to retirement, arguably really do have it right when it comes to asset allocation for accumulators. Reducing equity exposure in the final years – as the portfolio gets largest and most sensitive to return volatility – is an excellent means to narrow down retirement date risk.

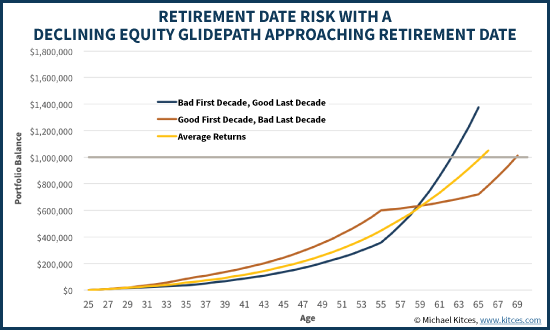

For instance, assume the earlier accumulator saving $300/month into a 60/40 portfolio begins to take equity exposure down by 3%/year in the final decade leading up to retirement. Each 3% equity reduction will reduce the expected return of the originally-60/40 portfolio by about 0.15% (from the original 8%), and the standard deviation by about 0.5% (from the original 12%). The impact of this on the trajectory of the portfolio – including getting a plus-or-minus 2 standard deviation event – is shown below.

As the results reveal, implementing this form of decreasing equity glidepath in the final accumulation years leading up to retirement significantly reduces retirement date risk, which is cut down from an 8-year time window to only 6 years! The "early" retirement scenario for good returns begins at age 63, but the bad return scenario only delays to age 69.

On the other hand, the reduced returns associated with getting more conservative in the final years do delay the retirement date slightly – as it moves from age 65 to age 66 instead. For most accumulators, this is probably an acceptable trade-off to manage retirement date risk. Though notably, the prospective retiree could also try to ramp up savings in the final decade to help make up the difference – an increase in the monthly savings rate from $300/month to $415/month in the final decade is sufficient to bring the retirement date back to the original age 65, even with the decreasing equity exposure in the final years. (Notably, the increasing savings requirement is material - a nearly 40% boost to required saving - precisely because the portfolio is so large that even just moderate shifts in returns have an outsized impact on the outcome.)

Ultimately, though, the fundamental point is simply this: for investors that have no cash flows coming out or going in to a portfolio, it’s feasible to just wait for long-term returns to manifest. However, for retirees taking distributions, or accumulators making contributions, the cash flows moving in/out of the portfolio introduce a sequence of return risk, which is only amplified for accumulators relying on very-long-term returns to compound their way to a targeted retirement date. And the greater the portfolio volatility, the greater the associated retirement date risk.

Which means in the end, portfolio volatility is not merely a risk to be taken and “waited out” through a series of adverse market returns – instead, proactively managing portfolio volatility, and the retirement date volatility it creates, can be a meaningful way to manage retirement date risk as well!

So what do you think? Is it helpful to think about portfolio volatility for accumulators as a form of “retirement date risk”? Would your clients consider their exposure to volatility in the final years before retirement differently if they considered the retirement date risks that result from aggressive portfolios?