Executive Summary

Over the past few decades, advicers have used Monte Carlo analysis tools to communicate to clients if their assets and planned level of spending were sufficient for them to realize their goals while (critically) not running out of money in retirement. More recently, however, the Monte Carlo "probability of success/failure" framing has attracted some criticism, as it can potentially alter the way that a client perceives risk, leading them to make less-than-ideal decisions. In reality, retirees rarely experience true failure, and instead find that they may need to adjust their spending (in both directions!) in order to meet all of their goals. And while some have suggested pivoting to a more accurate "probability of adjustment" framing, there is a simpler way to talk about "retirement income risk" that relies on the concepts of overspending and underspending, which can help both advicer and client better understand the trade-offs inherent in the ongoing decisions around spending in retirement.

Determining whether clients are overspending or underspending during their working years is relatively straightforward and is simply a matter of observing if they are spending more or spending less than they make. However, once the client retires, the "how much they make" part of the equation becomes much less clear. But by accounting for all of a client's income sources and balancing them against their various spending goals with a set of future assumptions around such factors as life expectancy and market performance, the advicer can arrive at a "best guess" answer to the question of how much the client should be spending. From a mathematical standpoint, that best guess is the level at which a client is equally likely to overspend as they are to underspend. Yet, in the Monte Carlo success/failure framework, that balance point exactly represents a 50% probability of success, which seems intuitively 'wrong' given that the analysis targeted the precise spending level that would preclude both overspending and underspending!

The Monte Carlo success/failure framing, in essence, focuses only on minimizing the risk of overspending, hiding a bias towards underspending by calling it a "success". Or, put another way, a 100% probability of success is exactly a 100% probability of underspending. Which means that solving for higher probabilities of success generally necessitates underspending to the point where clients, while comfortable knowing that they almost certainly won't run out of money, may have to significantly revise their desired expectations for their standard of living. By contrast, the overspending/underspending framework allows advicers to mitigate the Monte Carlo bias toward underspending while using concepts that clients are already familiar with. For instance, an advicer might communicate that their job is to help the client find a spending level that balances their goals of living the life they want while not depleting their resources.

Helping a client determine a balanced spending level in retirement is only the beginning of the journey. As time goes on, odds are that various factors (including circumstances, expectations, market returns, and inflation, to name just a few) will require spending levels to be adjusted. And by relying on the overspending/underspending framework, advicers can communicate how clients will be able to make those adjustments over time and, in the process, minimize the biases that incentivize lower spending that ultimately prevent them from living their lives to the fullest!

For decades, the dominant way for financial advisors to think about and measure risk in retirement – and to communicate risk to clients – has been through a probability-of-success score. But many have noted the numerous problems with this framing of risk, and some (myself among them) have even called for abandoning it altogether.

Problems with probability-of-success scores range from psychological (this framing can elevate clients' perception of risk and potentially lead to poor decision-making) to the fact that it doesn't reflect reality (few retirees actually fail – instead, they adjust). In a world where retirees adjust spending to accommodate changing circumstances, some have explored the possibility of simply renaming "probability of failure" to "probability of adjustment". However, there are technical reasons why even this shift, though tempting, is probably not quite right.

But there is an alternative framing of risk in retirement and a vocabulary for talking about risk with clients that both reflects "retirement income risk" more accurately and uses everyday language that clients can understand, avoiding jargon and statistics as much as possible. This vocabulary revolves around the concepts of overspending and underspending, and helps advisors and clients understand the basic trade-off between current standard of living and the future risk of a pay cut that is involved in all decisions about retirement spending.

Overspending And Underspending During The Working Years

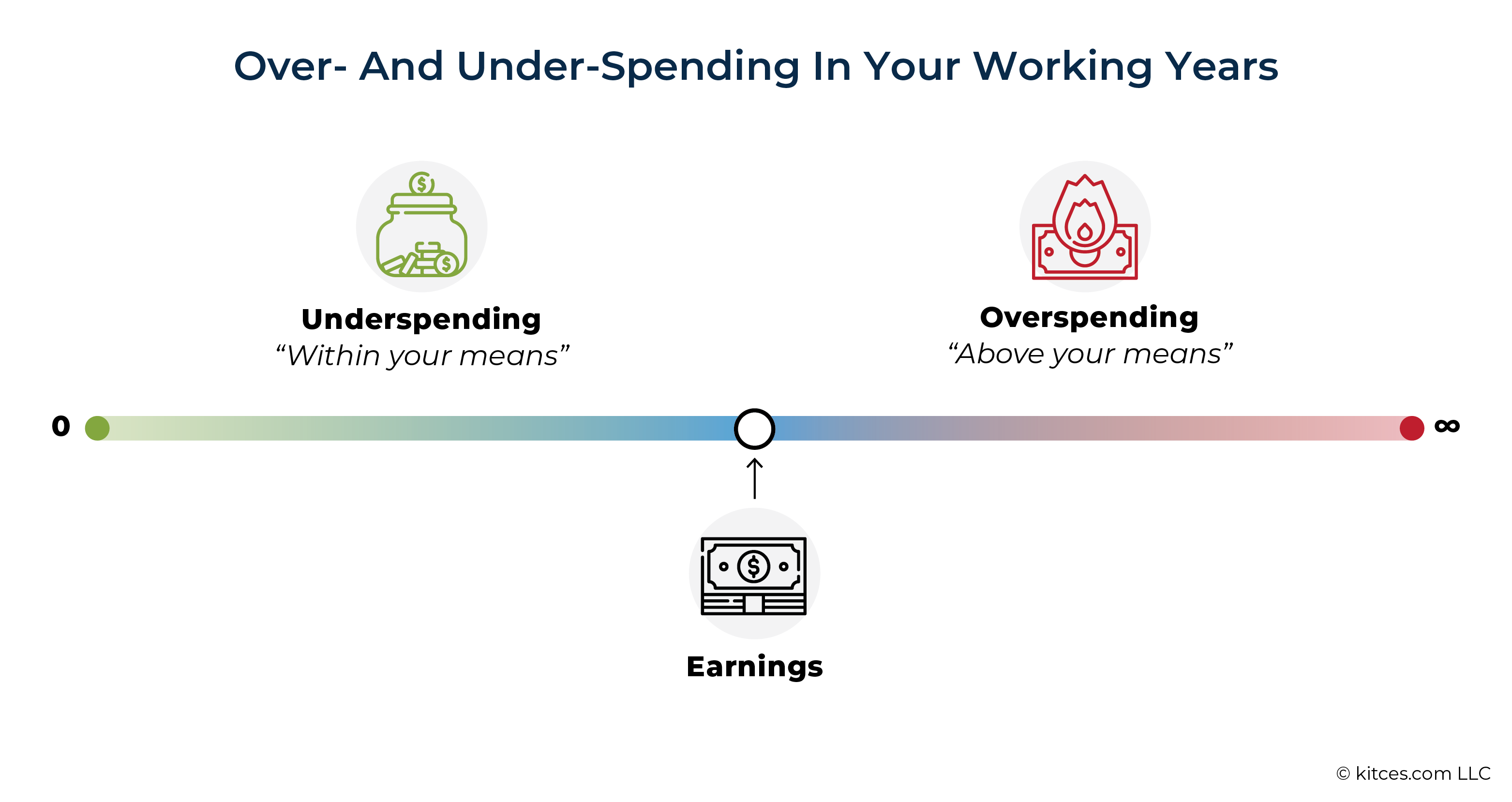

In a typical person's working years in a country like the United States, the question of what they can spend is not particularly difficult. As my grandma says, "Just spend less than you make." If "spending" is just total consumption, savings, and taxes, then this is a great piece of advice.

Before retirement, there are certainly important questions about how much an individual should save, whether to take on or pay off debt (like a mortgage), how to manage risk, and other mainstays of accumulation-phase financial planning. However, it is usually clear in this phase of life whether someone is overspending (spending "above their means") or underspending (spending "within their means". If an individual spends more than they earn, they are overspending. If less, they are underspending. If they're acting prudently, spending will be at or below earnings. Easy, right?

This is only easy because, for most people, earnings are well defined in their working years. During this phase of life, it's usually pretty easy to answer the question, "How much do you make?".

Finding The "Best Guess" For How Much Someone Can Spend In Retirement

While it's easy to determine how much someone can spend during their working years, once they stop working – or work less – and start depending on other resources to fund their living expenses things change. Now it's not at all clear how much they "make". That's why the first thing someone nearing retirement often wants to know is, "How much can I spend?" Until they have a "best-guess" answer to that question, it's impossible to know whether they're over- or underspending in retirement – living within or above their means.

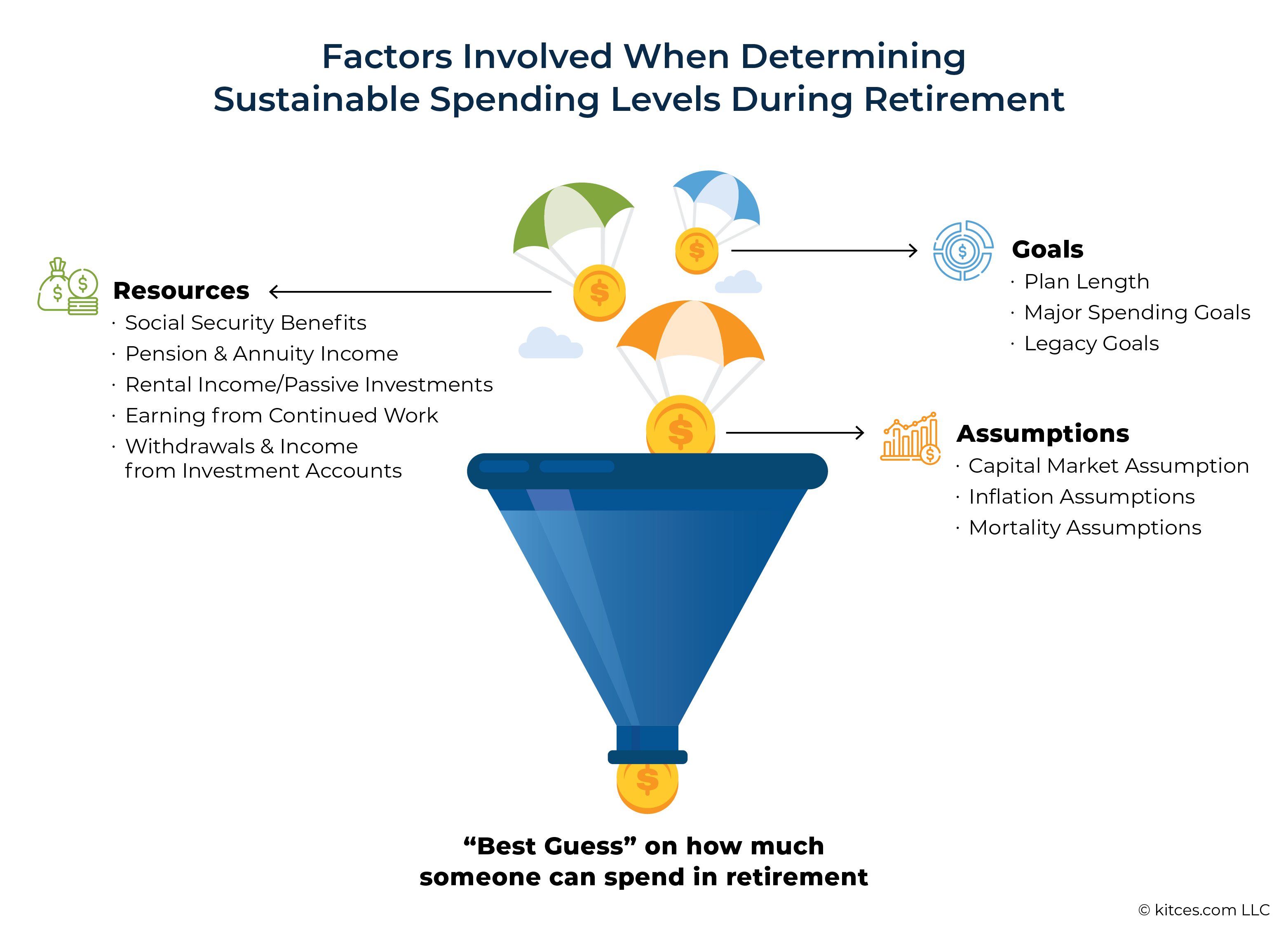

In a typical retirement, resources that can fund living expenses include things like Social Security benefits, pension and annuity income, rental income or other passive investment income, earnings from continued work, and withdrawals and income from investment accounts. Along with a full accounting of these resources, an advisor also needs to account for major goals, like the number of years the clients may need to fund their spending, and any major spending or legacy goals. Once these resources and goals are combined with a set of assumptions about how the future could look (capital market assumptions, inflation assumptions, mortality assumptions), computer software can help the advisor arrive at a "best guess" for how much this retiree can spend.

But what is this "best guess"? It's the amount of spending (full-plan consumption + taxes + special spending goals + legacy goals) that is, mathematically speaking, equally likely to be underspending or overspending the household's resources.

One way advisors have traditionally calculated this "best guess" is to use time value of money calculations using straight-line appreciation. Ignoring the complications of non-portfolio income, this calculation might go like this: If the expected (geometric) average annual return is 5.2% (equivalent to a 6% arithmetic average with 12% standard deviation), the PMT function on a financial calculator tells us we can withdraw about $63,500/year from a $1 million portfolio over 30 years. "Expected" return is just another way to say "best guess" return. So, this calculation gives us the "best-guess" spending level.

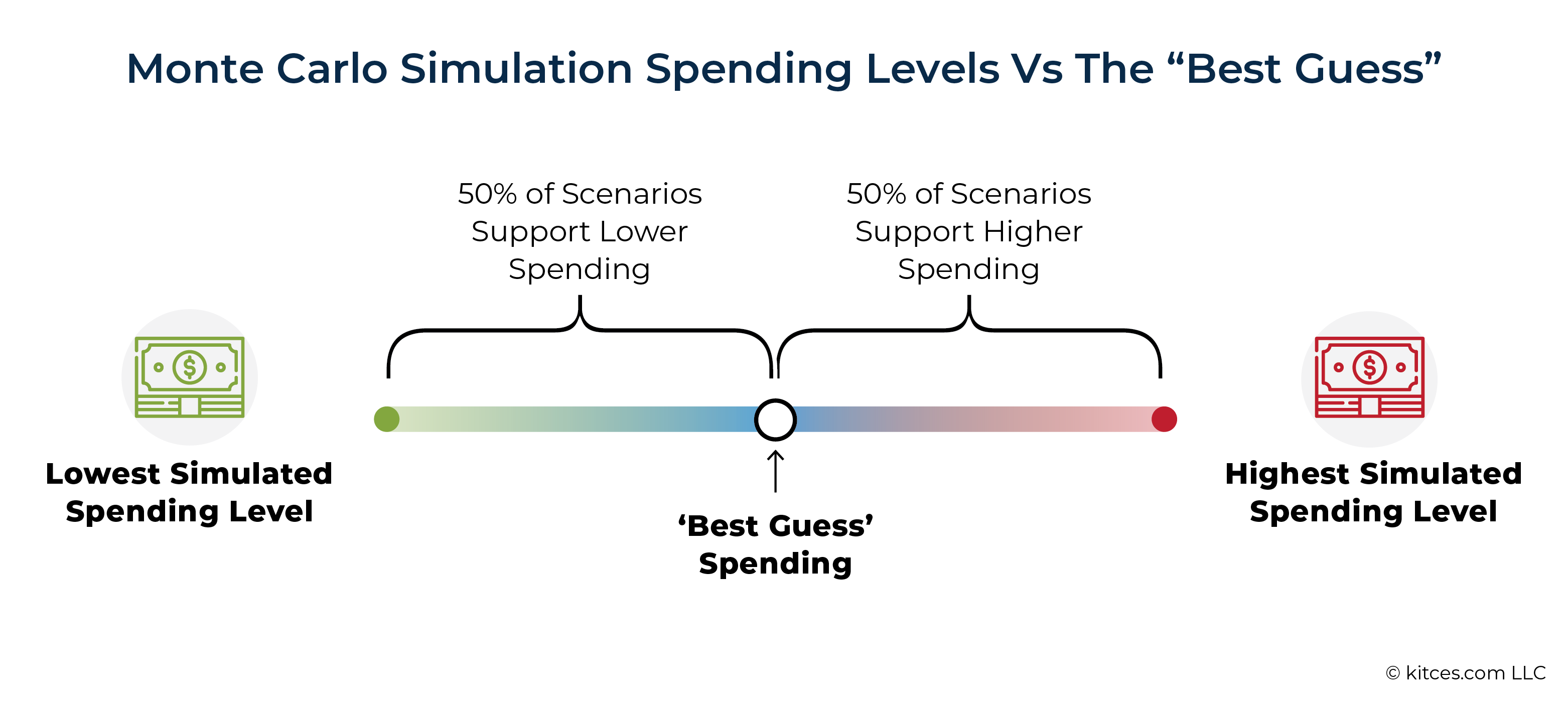

In a Monte Carlo simulation that assumes 6% arithmetic average returns and a 12% standard deviation, this $63,500 annual withdrawal plan has a 50% probability of success. In other words, in success/failure framing, the spending level that has a 50% probability of success is the "best guess". This spending level balances the risks of over- and under-spending.

The idea that a spending level with a 50% probability of success is, in fact, the "best guess" for how much someone can spend in retirement may initially strike some readers as wrong. But keep in mind that the mathematical "best guess" may not be the same as the "best plan" for a retiree. As discussed below, there are some good reasons an advisor may counsel spending below this median spending level.

But first, let's convince ourselves that this truly is the best guess, mathematically speaking. In a Monte Carlo analysis, for each individual scenario, with its specific set of randomized returns and inflation, there is an amount that one could spend and hit all of the plan's goals without leaving any excess resources "on the table" at the end of the plan.

For some scenarios, where sequences of returns and sequences of inflation are worse, this "ideal" spending amount will be lower. For others, it will be higher. If we know the ideal spending amount for each scenario in a Monte Carlo analysis, 50% will be lower than the "best guess" (median) number and 50% will be higher.

So, if we wanted to choose a spending level that balances the risks of overspending and underspending, we would choose the median.

Over- And Under-Spending In Retirement

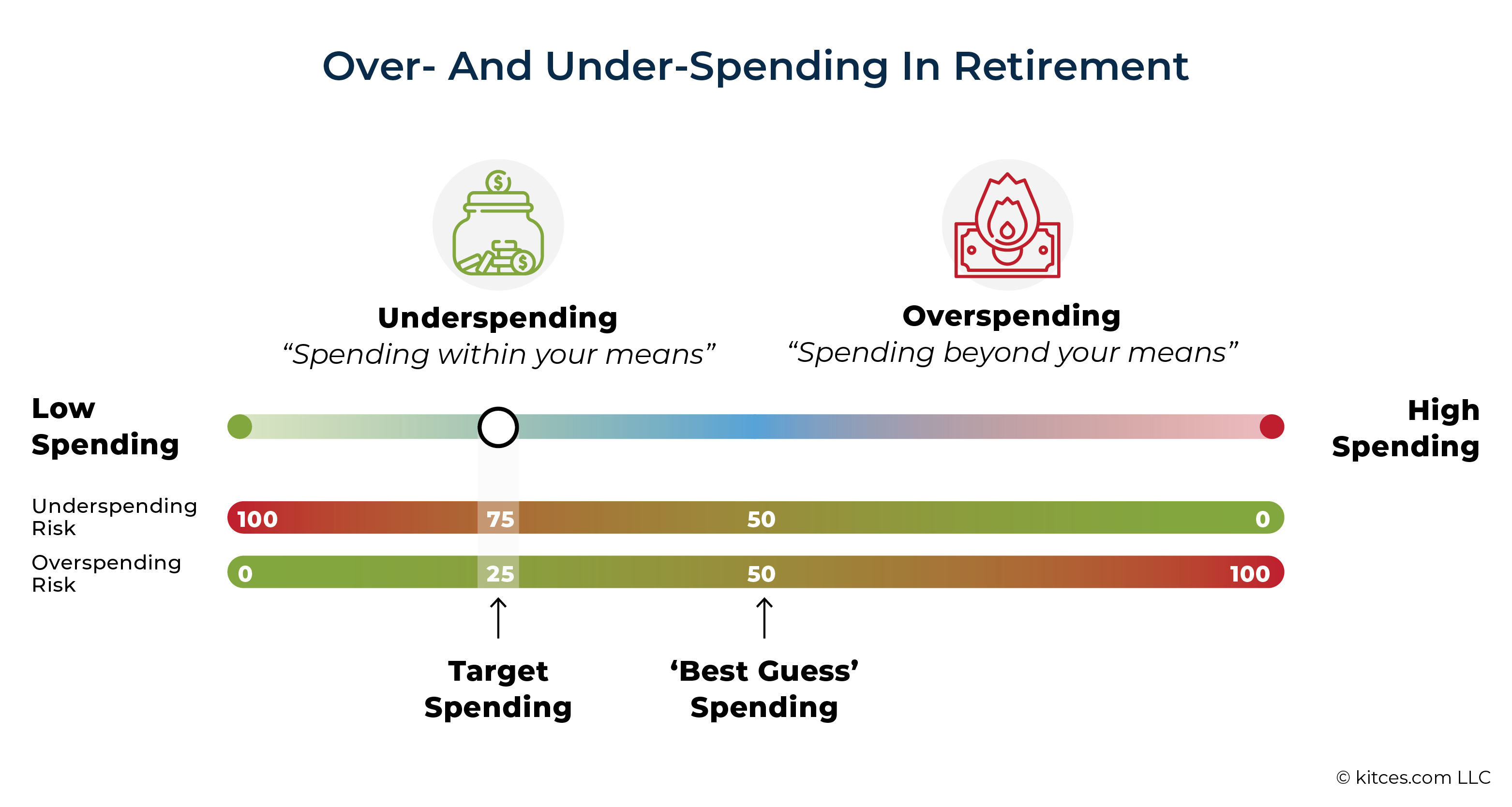

There are 2 types of income risk in retirement or, rather, 2 sides of the income risk coin: 1) the risk of overspending one's resources and 2) the risk of underspending them.

Overspending means that at some point now or in the future, the retiree will have to trim spending in order not to overtax their resources. Underspending means the retiree is being overly frugal, forgoing expenses and experiences that could possibly improve their quality of life and time spent with friends and family. By underspending, a client builds up resources that will never be used and will likely leave more of a financial legacy than they had intended.

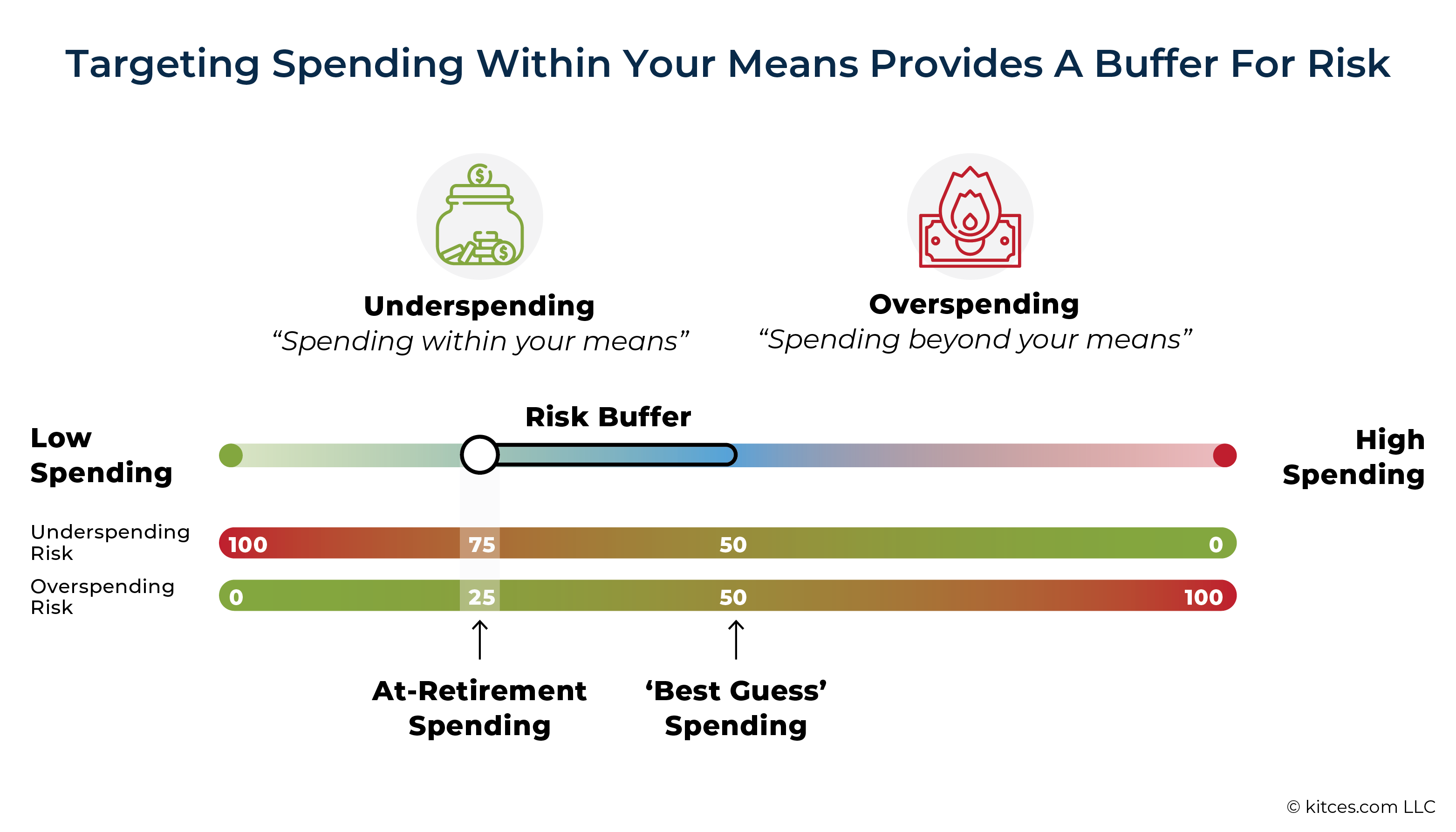

Because most people fear the consequences of overspending more than the results of underspending, many advisors and clients prefer to target a spending level below the "best guess". After all, living within or below one's means is prudent since it builds up a buffer against surprise expenses or changes in fortune.

This is one reason that, when Monte Carlo analysis was introduced in financial planning, many advisors pivoted from straight-line appreciation calculations that produce a "best guess" spending level, as in the example above, to finding spending levels with 70%, 80%, 90%, or higher' probabilities of success'. But this preference is not limitless. Few are willing to embrace deep underspending and forgo all comfort, fun, and travel in exchange for leaving an unlimited amount behind when they die. Most people would instead seek a balance between the enjoyment of their resources and avoidance of major reductions in their standard of living. This balance would typically mean targeting spending that is within one's means, but not too far below them.

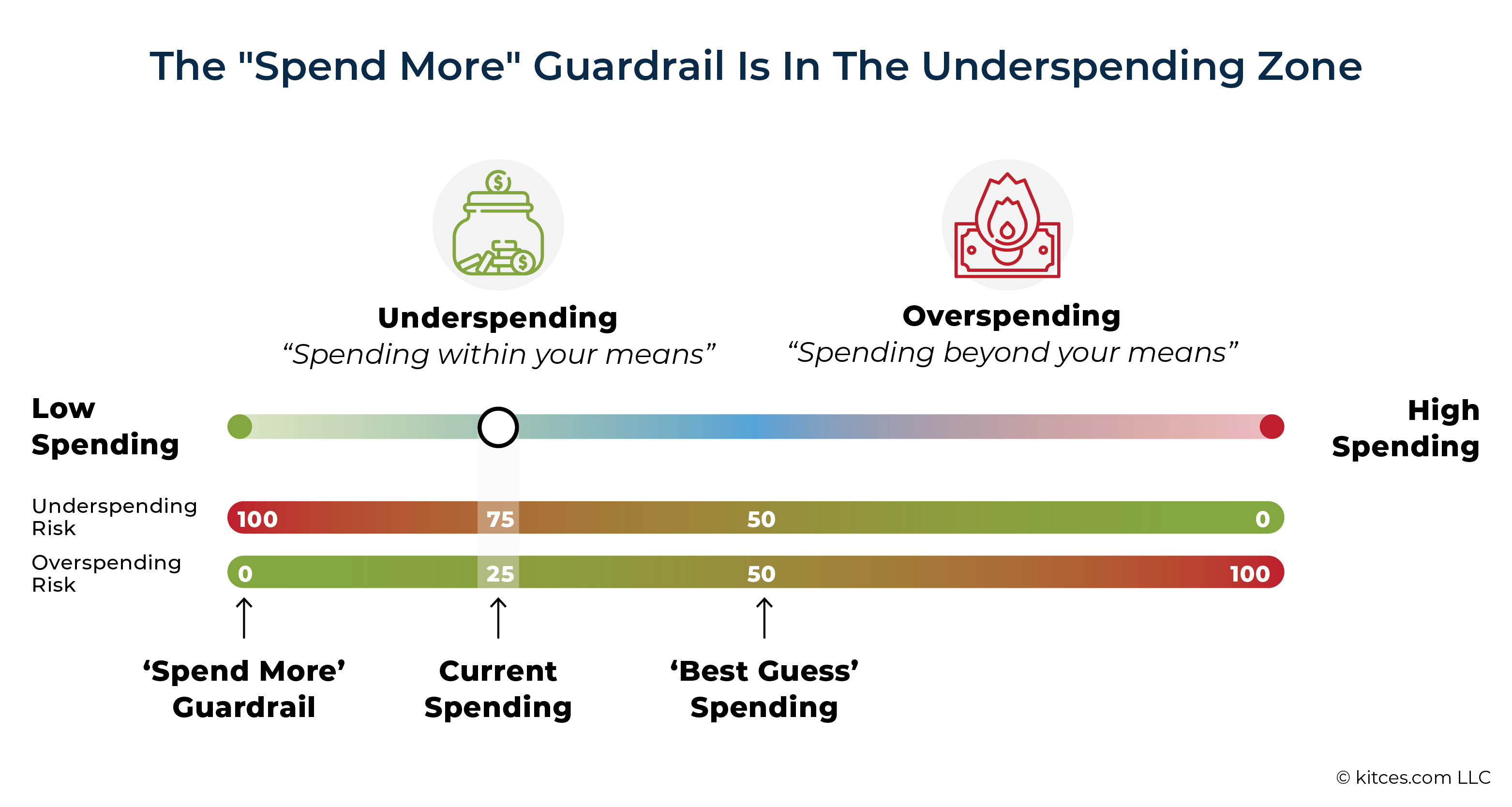

For example, the risks of underspending and overspending are shown below on complementary 100-point scales, with a target spending level mid-way into the "underspending" zone.

By sticking to this overspending/underspending framework, an advisor can talk about spending in retirement with clients using everyday language that isn't all that different from what they might say before retirement:

Our first goal in planning for your retirement is to figure out how much you can spend. Unlike in your working years, where you just try to spend less than you make, this requires some work. But we can do it.

We'll start by accounting for all of the resources you can use to fund your lifestyle in retirement – Social Security, pensions, investment accounts, and so on – and any large, important goals you have. From those resources and goals, we'll have a good idea of what you can afford to spend on day-to-day living and how you'll fund that spending over time. We'll target a spending level that balances your goal of living the best life you can with the goal of not overspending your resources.

In other words, we'll find a spending level that is neither too hot nor too cold.

Note that this method of communication doesn't use the words "success" or "failure". Probability-of-success language focuses only on minimizing the risk of overspending. It hides underspending risk by calling it "success", and so biases plans toward underspending. In fact, one could say that 100% probability of success is 100% risk of underspending. In contrast, the dual language of "overspending" and "underspending" used above focuses instead on balancing the desire to live a good life, given the resources available, with the wish to avoid the heartache and headaches that come with spending cuts.

Additionally, this language doesn't introduce abstruse statistics or confusing jargon, neither of which is likely to improve client understanding or confidence.

Balancing the risks of overspending and underspending in retirement spending decisions is analogous to balancing risk and return in investment decisions. Taking on too much investment risk introduces the possibility of clients not being able to stomach volatility. But taking too little risk (such as investing 100% in TIPS) may put them at risk of not having enough resources to live the life they could. As the saying goes: nothing ventured, nothing gained. And many investors choose to take on some risk in exchange for possible gain. If 'probability of success' were applied to investment risk, it would be called "probability of not losing money". While avoiding loss is certainly in the conversation, it is not the only goal at play in investment decision making. The same is true for retirement spending decisions.

Over- And Under-Spending As Triggers For Spending Adjustments

Giving advice on how much someone can spend when they retire is only the beginning. Over time, as circumstances change, the risk of continuing to follow the same plan without adjustment will change. Underspending/overspending language can be used to describe how things change and how an advisor will guide adjustments over time.

For example, imagine someone is spending $10,000/month in retirement from a combination of Social Security, pensions, portfolio withdrawals, and other resources. As this retiree's account balance changes due to investment returns and withdrawals, as inflation changes the purchasing power of this $10,000, as actual withdrawals happen, and as the plan length changes with the client's age, this $10,000/month amount will move on the underspend/overspend line. If the risk of continuing to follow the plan without change goes down, it will move toward underspending. If this risk is going up, it will move toward overspending.

Imagine there was no inflation, and returns exactly kept up with withdrawals so that this retiree's portfolio balance stayed flat. We would expect this $10,000/month to move more and more toward the left (underspending) as their plan gets shorter and shorter. After all, spending $10,000/month is much less risky at age 75 than at age 65, all else being equal. Eventually, this spending level will so underutilize the client's resources that it will be time to tell them they can spend more and "live a little".

When you retired, you may remember that we did a lot of work to figure out what you could afford to spend. Now that you're living in retirement, my job is to make sure you continue to live within your means, but also that you are able to do what you'd like to do, if you can afford it!

We've been monitoring your plan for a few years now, and I'm happy to say things have been working out great. Your portfolio has done well, and inflation hasn't had much of an effect. So, I have good news: because things have gone well, you can spend $1,000/month more than you are now – that's an extra $12,000/year – and still be taking no more risk than you were taking when you retired.

I'd recommend thinking about some meaningful ways to spend that money. I know you mentioned remodeling the main-floor bathroom and a trip to Italy last time we talked. If we don't see major changes in markets and inflation, I think you could do those over the next year or 2.

This approach uses risk-based guardrails to manage spending. When risk goes down substantially, a retiree can increase their spending so as not to under-utilize their resources. And when risk rises substantially, they can trim their spending so as not to over-tax them.

The example above shows that the 'spend-more' guardrail is in the underspending zone. If continuing to spend the same amount gets less and less risky, at some point, it's time to give clients some good news.

But, of course, the opposite could happen, too, and risk could go up over time. Higher-than-expected inflation, poor investment returns, and higher-than-expected portfolio withdrawals due to unexpected expenses could all make continuing to spend $10,000/month look more and more like overspending. But if this retiree began retirement with a relatively conservative spending level, below the 'best guess', they started retirement with a 'risk buffer'. This buffer means that things can get worse and, up to a point, the client will still be living within their means.

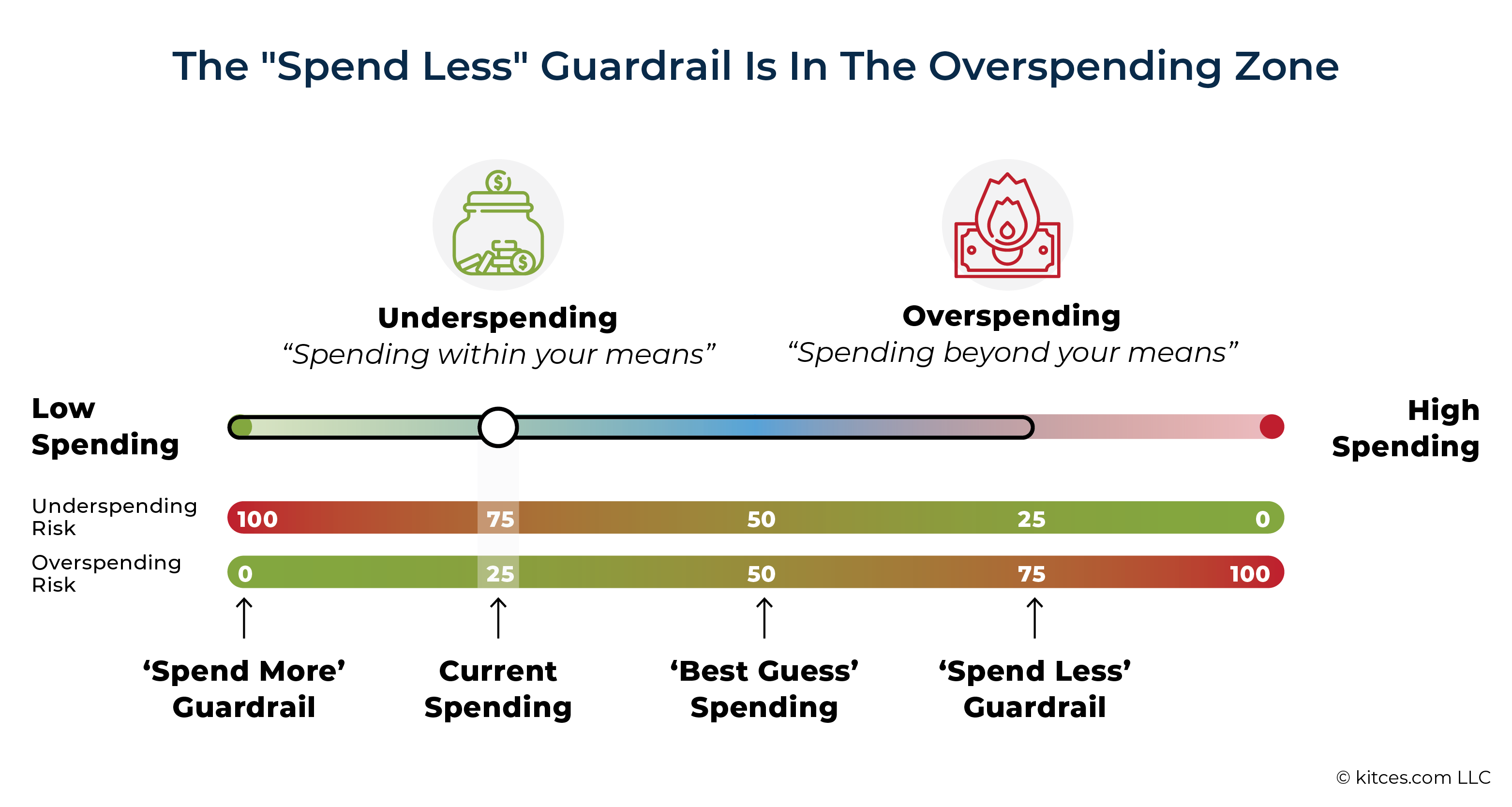

Within this picture, it's clear that triggering a reduction in income anywhere to the left of the 'best guess' would be an overreaction. Yes, risk may be rising. But the client is still spending within their means. It is only after risk rises into the overspending zone that an adjustment begins to look reasonable.

However, because short-term market movements and inflation spikes can reverse themselves, advisors will typically want to delay advising reductions in spending until it is clear that risk really has risen high enough that belt-tightening is not an overreaction. That means the 'spend-less' guardrail will be somewhere within the overspending zone.

Here, we can see why the underspending/overspending framing of risk in retirement is useful not just to clients but to advisors as well. Words matter, and if we're not careful they can inject distortions in how we think. In the schema above, the "spend more" guardrail is triggered if underspending risk is too high (shown above at 100). The "spend less" guardrail is triggered if overspending risk is too high (shown above at about 75).

What is marked as "underspending risk" here would, in a success/failure framing, be called 'probability of success'. If this guardrail were stated using probability-of-success terms, the "spend-less" guardrail would be at 25% probability of success. Few advisors or clients could stomach seeing that score on their computer screen. But when risk is understood as a "chance that you are overspending", or maybe even "confidence that you are overspending", adjusting at 70%, 60%, or even 50% probability of success looks irrational: Those 'success' levels correspond to a 30%, 40%, and 50% chance that the client is overspending. At 50%, they've just arrived at the model's 'best guess'. That's the point at which they are neutral as to whether they are over- or under-spending, not a point when emergency alarm bells are sounding.

From the diagram above, we can see that choosing a beginning-of-retirement spending level that is below the 'best guess' sets the client up to expect more good news than bad. They are closer to a 'spend-more' guardrail than a 'spend-less' guardrail. Of course, circumstances could certainly push risk to the 'spend-less' guardrail, and at this point, the advisor has bad news for the client. But, if expectations were set correctly, this wouldn't be a surprise. The client will know that their current spending has been getting riskier.

As you know, we monitor your situation regularly to make sure we adjust retirement spending so you're not overspending or underspending your resources by too much. In our last meeting, we pointed out that these rough markets have hurt your portfolio and that that could mean we will want to trim spending at some point. We believe we've reached that point, and the risk of continuing your current withdrawals and spending is too high.

We recommend reducing spending from $10,000/month to $9,200/month. That will move you back toward living within your means.

To this, a client might well respond, "Are you sure that's enough of a cut?" Just like with any spending decision, adjustments are always a balance between the risks of overspending and underspending. A huge reduction in spending is likely to get overspending risk under control, but it could also be an overreaction that would have to be undone in the future. An advisor could explain this balance and remind the client that adjustments aren't necessarily "one-and-done".

We believe this adjustment might be enough to keep things on track for a while and get us through this rough patch. If it does, we'll be happy we didn't overreact. We think it's better to make multiple adjustments than to adjust by too much all at once. We can always adjust again.

If markets continue to suffer or inflation rises, we may need to trim spending further in the future. On the other hand, if markets recover, we may be able to increase spending again in the future. We'll be tracking this closely.

Using guardrails as in this example to keep the risks of overspending and underspending in balance is a bit like setting heating and air conditioning temperatures on a thermostat. For example, maybe heat kicks on a 65 F ("Too cold! Time to heat things up.") and AC at 78 ("Too hot! Time to cool things down."), but, in between, the temperature is allowed to fluctuate without intervention. A great thing about using risk of overspending and underspending to trigger adjustments is that this doesn't just make sense in theory, it also works in practice.

There's much more than can be done with guardrails and adjustment-based planning to set clear expectations for clients and to design and manage adjustment plans. However, the key point is to encourage a realistic, plain-language approach to thinking and talking about risk in retirement – a vocabulary that centers on whether someone is over- or under-spending.

This framing of risk in retirement eliminates the biases that can creep in when using probability of success to measure and communicate risk. Those biases incentivize low spending and higher-than-desired legacies by focusing only on minimizing the risk of overspending without pointing out the costs and regrets that can come from underspending.

A one-sided measure of risk like probability of success – or even probability of adjustment – can hide the need for balance. In contrast, the language of over- and under-spending allows advisors to make the trade-offs in spending decisions clear and help clients balance those trade-offs and adjust their spending over time.

Leave a Reply