Executive Summary

A common concern many individuals have when contemplating retirement spending is that they may live longer than expected and thus risk outliving their money. This sentiment can lead advisors to build financial plans based on the conservative assumption that clients will live a very long time. Yet, while a longer plan will extend the longevity of the portfolio, it also relies on lower annual portfolio withdrawals. For couples, it becomes crucial to consider other income sources, such as Social Security benefits, annuities, and pensions, that may be reduced or eliminated when one spouse dies. The loss of these additional income streams by one spouse can create a significant mortality risk for the surviving spouse, potentially leaving them with less income than expected. Which means that plans that anticipate both members of a couple living to the same (very old) age might overlook the mortality risk of one spouse dying earlier than planned, which can significantly influence the surviving spouse’s sources of income and overall financial situation.

To manage these potential outcomes, advisors can use a more rigorous process to account for and manage both longevity and mortality risk. For example, advisors can calculate a client's spending capacity using expected mortality-adjusted cashflows to manage mortality risk. Rather than giving a plan 'credit' for all non-portfolio income that would be received if clients live to their projected date of death, advisors can instead average out the non-portfolio income that a couple would receive across a wide range of mortality assumptions based on statistical probabilities that treat death as variable and uncertain. Using a comprehensive approach to examine a client's mortality risks can be an opportunity for the advisor to highlight potential pain points and vulnerabilities and offer clients a strategy to plan for them.

In addition to examining the factors that shape mortality risk, advisors can also weigh several factors when assessing a client's longevity risk, from demographic trends (e.g., projecting life expectancy based on the client’s sex and affluence) to health and family history and even to the client's own tolerance for longevity risk. Advisors can establish a systematic process to adjust and optimize plans for longevity, customizing the plan length for clients beyond choosing arbitrary default age settings in their planning software packages.

Ultimately, the key point is that creating a plan based on how long a client will live is most effective when both mortality and longevity risk factors are considered. Actuarial science offers tools that can help advisors assess these considerations so that they can adjust mortality assumptions and longevity expectations as part of an ongoing process of monitoring and updating a plan. And by making these adjustments collaboratively and regularly, advisors can help clients develop a relevant and realistic strategy to manage their mortality and longevity risks as they journey into retirement!

"What if I live longer than expected? I don't want to outlive my money."

This not uncommon sentiment can lead advisors to build financial plans that assume clients will live a very long time. After all, a longer plan will have lower portfolio withdrawals, which extends the longevity of the portfolio.

But portfolio withdrawals aren't the only retirement resource. When planning for a couple with Social Security, pensions, or other income streams that change when someone dies, there is an additional cost of planning for a long life. The opposite of longevity risk is mortality risk, or the risk of dying earlier than expected and leaving a surviving spouse with less income than expected. How can that happen? If both spouses receive Social Security, total benefits will go down when one spouse dies. Similarly, many pensions and annuities have less than 100% survivorship and often cease entirely when the recipient passes. If someone dies earlier than expected, non-portfolio income goes down and the portfolio will have to make up the gap. That can add unexpected stress to the portfolio and raise risk.

This means there is a conflict when deciding on how long to assume someone will live: longevity risk drives advisors to plan for longer lives, but mortality risk for shorter. What's an advisor to do?

One approach for advisors to solve this dilemma involves accounting for mortality risk when modeling expected non-portfolio income streams throughout a plan and adopting a more rigorous methodology for determining how long a plan should be (now and in the future).

What Would Happen To Mom If I Die?

While fear of outliving resources is real, the most salient concern for a couple planning for their retirement might be the wellbeing of a surviving spouse. When planning for my own parents, my father asked, "But, what would happen to Mom if I die?" This is an important question: My mother's family has a history of longevity (my great-grandmother lived into her 90s, and her sister lived to 104; my grandmother just turned 90), and my parents' retirement resources include a single-life pension and 2 Social Security benefits, resources that would be reduced or eliminated upon my father's passing.

How big of a risk is mortality risk? That depends on the make-up of a couple's resources. Consider the following example.

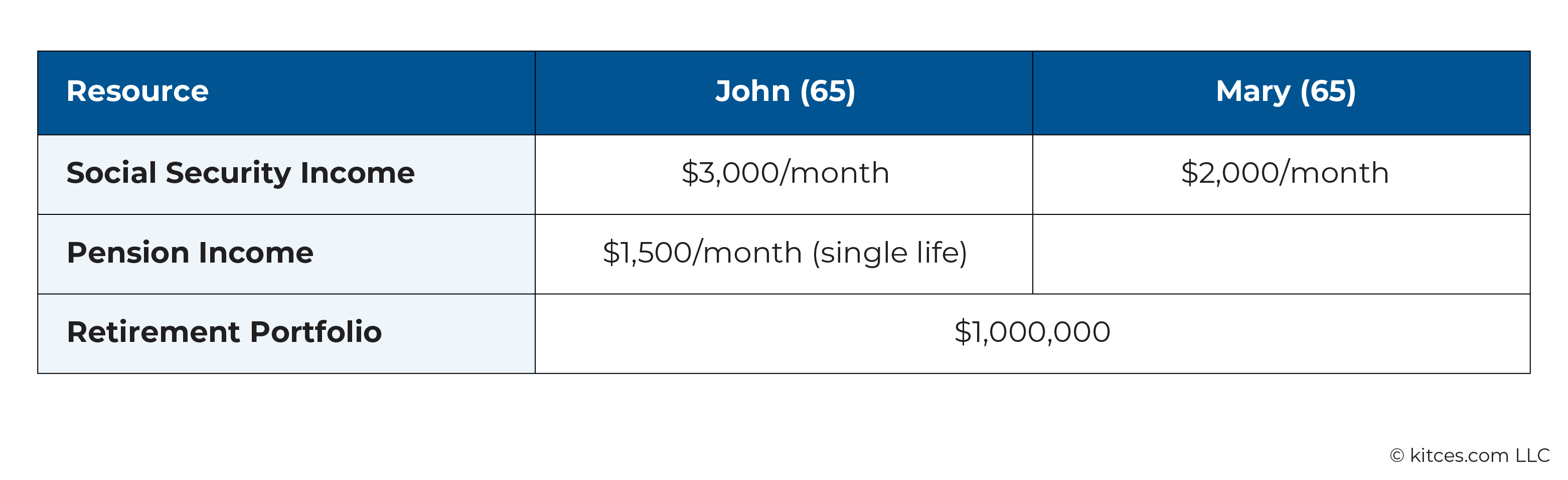

John and Mary, both 65, are married and have monthly Social Security benefits of $3,000 for John and $2,000 for Mary, a single-life pension that provides John with a $1,500 monthly income, and a $1 million retirement portfolio. They meet with their financial advisor and tell her they both expect to live to around age 95.

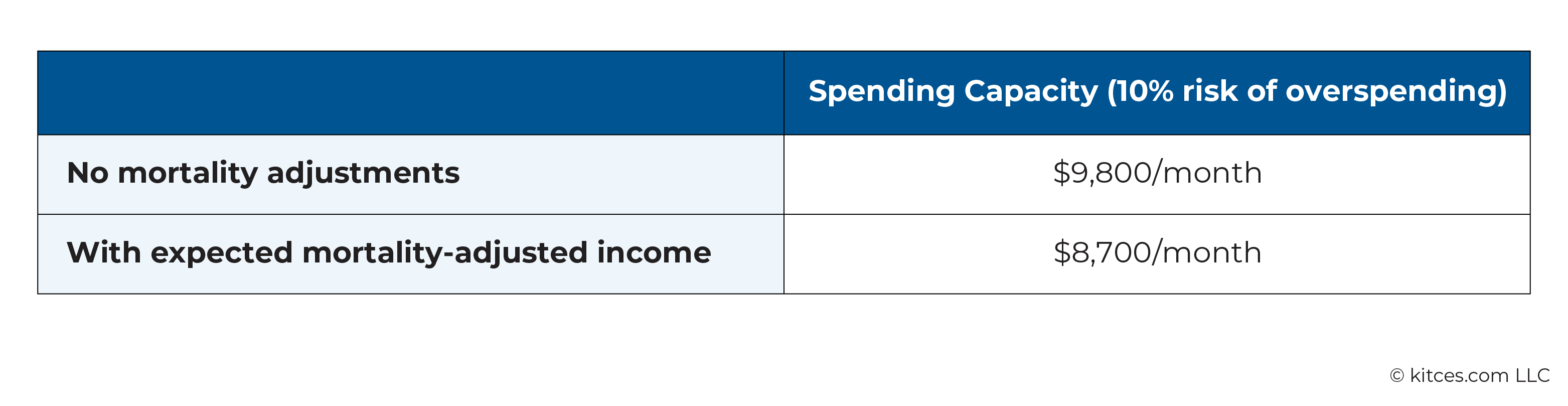

Based on John and Mary's estimated lifespan of an additional 30 years, the advisor determines that they would be able to spend about $9,800/month. (This assumes that their portfolio will average 5% real returns annually with a standard deviation of 10%, and that the couple targets a very conservative 10% risk of overspending/90% risk of underspending.)

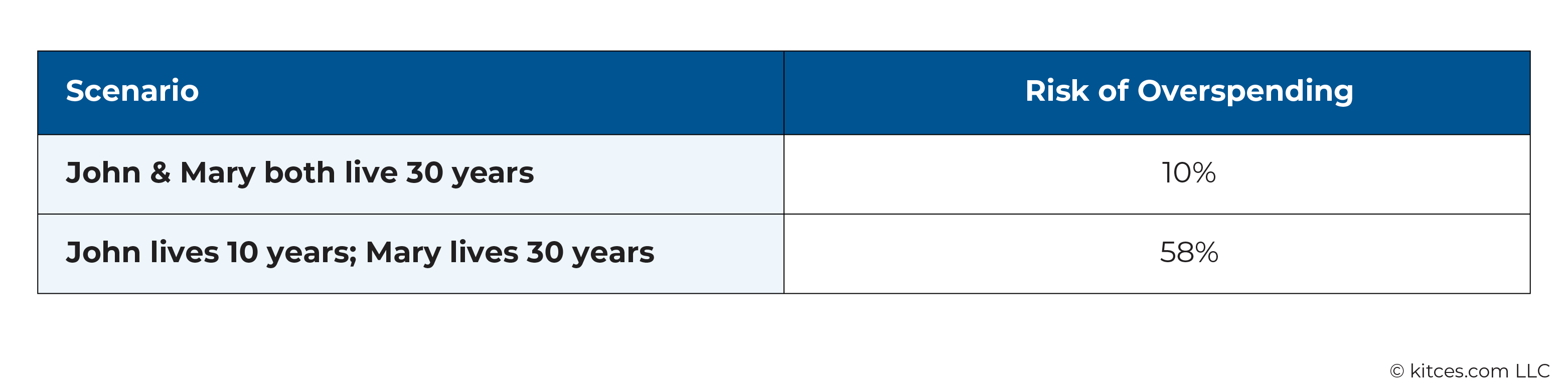

However, if John were to die before Mary, Mary would lose $2,000/month in Social Security benefits and the $1,500/month pension. That would be a huge change in income for Mary. What if, instead of living another 30 years, John dies at age 75, 10 years from now? The $9,800/month spending level (that had only a 10% risk of overspending if John lives 30 years) has a 58% risk of overspending if he lives only 10 years! (Mary's expenses may also go down after John's passing, but unless she spends $3,500/month less after his death, that won't make up all of the difference.)

The reason for this higher risk is that dying earlier than expected produces a loss of non-portfolio income from Social Security and the pension (not to mention increased costs from taxes, an issue we won't address here), meaning portfolio resources will be overworked to make up the difference. If we planned for John to die at 75, this couple's spending at the same targeted risk of overspending/underspending would be $7,600/month – 22% lower because of a difference in how long John lives.

Of course, we don't know if John will live to 95 or if he will die at 75 or at some other age. So, what is the right retirement spending advice for John and Mary? And, more importantly, how can advisors consistently give good advice to couples like this? The answer is to take both risks seriously by using a rigorous process for both longevity and mortality risk planning.

Treating Longevity-Dependent Income As Uncertain

Financial planning analysis has improved in the past by acknowledging uncertainty and risk. For example, awareness of sequence-of-returns risk led to safe withdrawal rate research and simulation analysis (like Monte Carlo analysis). More recently, software programs began accounting for sequence-of-inflation risk, or the risk that inflation could be higher or lower than expected, and change over time. John and Mary's situation above highlights the need to treat mortality-sensitive cashflows in financial plans as variable and uncertain. Just as no process for handling sequence-of-returns risk will accurately predict the actual returns someone will experience, no process can hope to accurately predict when someone will die. But any approach to mortality risk should at least adjust for the uncertainty of how long someone will live.

There are a few ways for advisors to account for the uncertainty of mortality when creating a client's plan. Bill Sharpe, in his online book "Retirement Income Analysis", suggests using probabilistic mortality simulations. This involves simulating, based on actuarial tables, how one or both clients dying before the end of the plan could affect a couple's spending capacity.

This approach is rigorous and not widely available to advisors in practice. Furthermore, some aspects of probabilistic mortality simulations can feel wrong to advisors and clients. A message like, "If returns are bad and inflation is high, you may have to limit spending 20 years from now. But you might also be dead by then, so that's not as bad as it sounds" doesn't inspire confidence. Dying before things get bad isn't an attractive financial plan. A much stronger planning message includes a clear longevity goal: "We have a plan that we think will last at least until you're age X."

Another way to plan for mortality risk, and one that works well with the assumption that one or both clients will live through the plan, is to calculate spending capacity using expected mortality-adjusted cashflows. Instead of giving a plan ‘credit' for all non-portfolio income (Social Security, pensions, etc.) that would be received if clients live all the way to their stated date of death, this approach averages out the non-portfolio income that a couple would receive across a wide range of mortality experiences (but excludes scenarios where both die before the plan's end). This means the plan acknowledges that we don't actually expect to receive all of that non-portfolio income with 100% certainty. This throttling of expectations leads to more conservative spending advice.

One advantage of this probabilistic approach is that we do not have to pick a firm date of death for the spouses. Instead, this approach treats death as variable and uncertain – probabilistic – instead of firm and certain. (Because of the computational efficiency of this method, this is the approach we use in my company's software, Income Lab.)

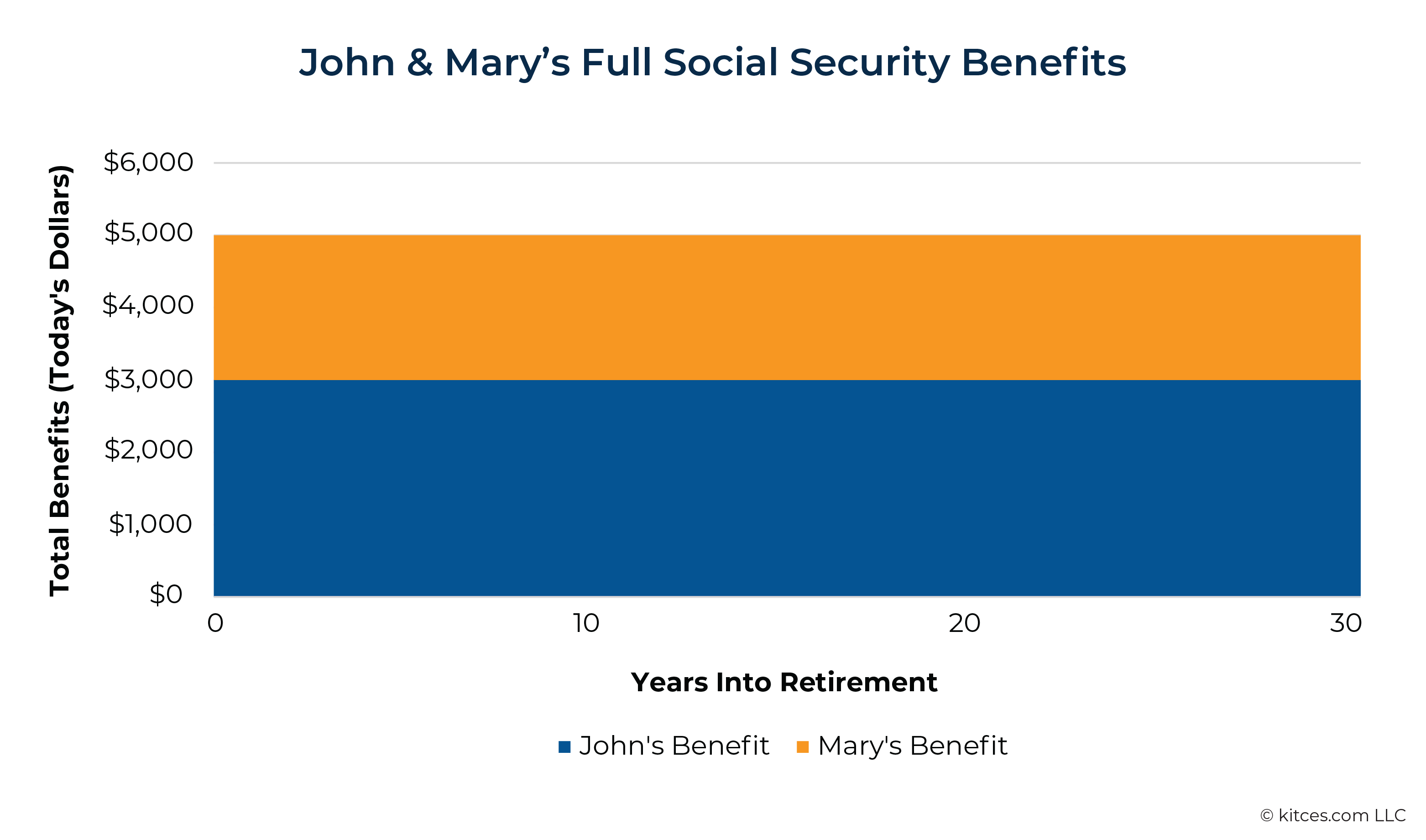

When calculating spending allowances for John and Mary, including full Social Security benefits would almost certainly overstate the amount the couple would receive over the next 30 years.

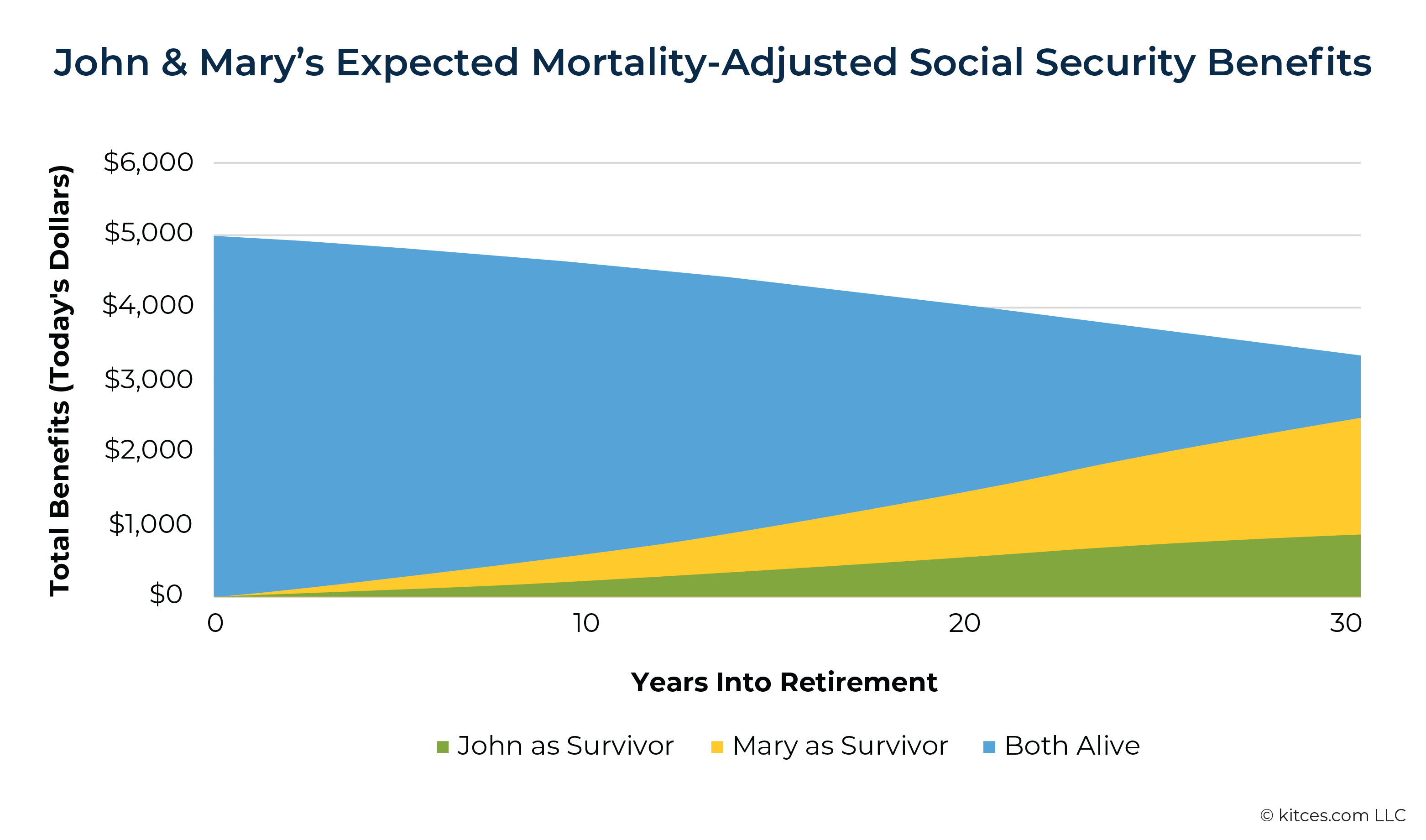

In contrast, expected mortality-adjusted Social Security benefits combine scenarios when both John and Mary are alive and those where John or Mary dies and the other received their own or a survivor's benefit. These amounts are scaled to the chances that these situations are true at any point in the future.

Here, we can see that early in the plan, mortality-adjusted benefits get ‘credit' for the full combined $5,000/month in Social Security benefits. That's because at this phase, and for the immediate years thereafter, the most likely situation is that both spouses are still alive and receiving benefits. However, as time goes on, the chances that Mary will become a widow receiving a survivor benefit increases. By the end of 30 years, the plan contains only $3,300 in total mortality-adjusted benefits, 43% of which is based on Mary receiving survivor benefits, 33% based on John as a widower, and the rest based on both spouses still being alive.

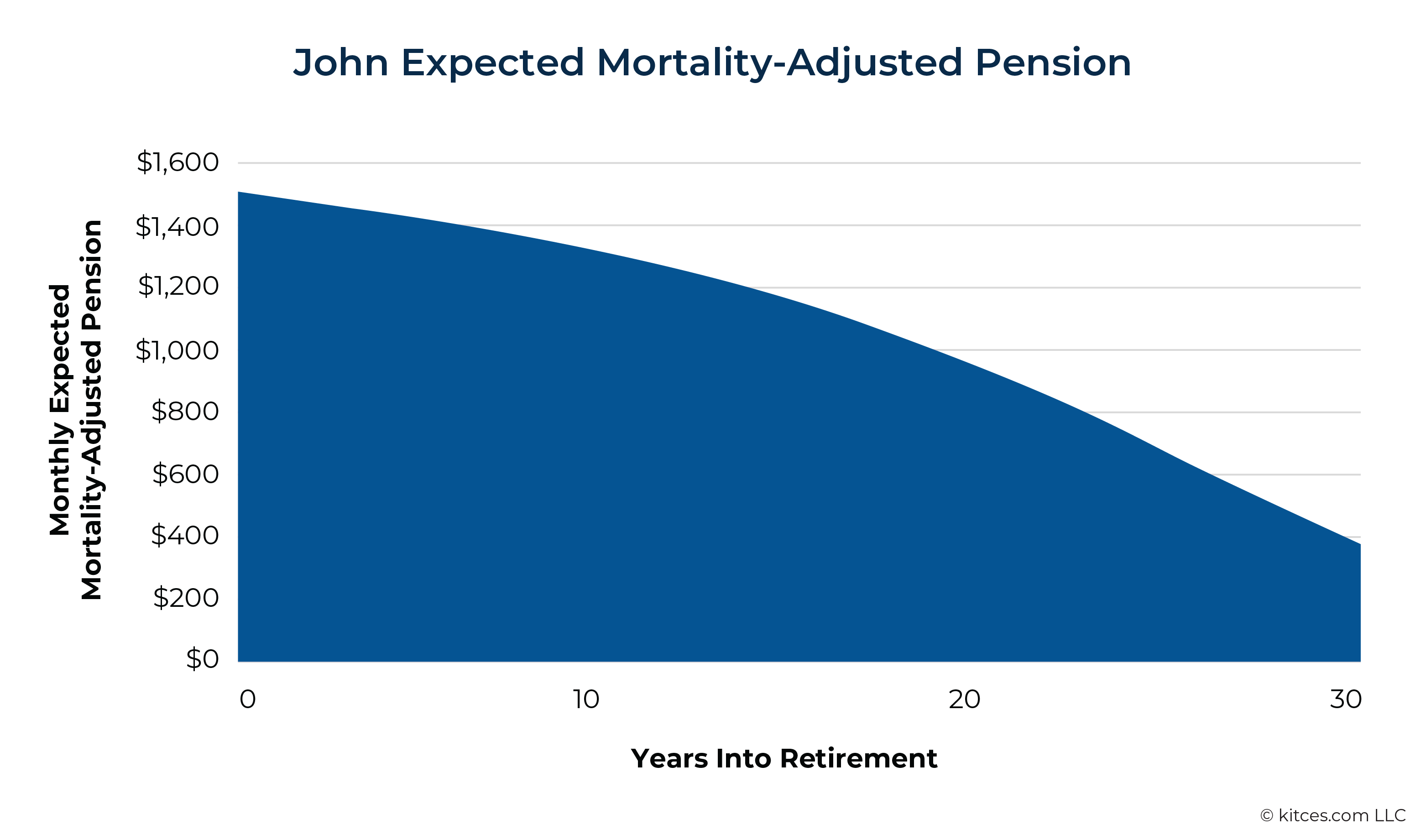

The expected mortality-adjusted single-life pension depends only on the chances that John is still around to receive those benefits at each point in the plan.

Using these mortality-adjusted cashflows for the analysis, spending capacity is $8,700/month, not $9,800/month. Taking mortality into account trims $13,200/year (12%) from this couple's spending.

This difference is based on simply acknowledging that people are mortal, and tomorrow is not guaranteed. The length of a plan is not the same as the amount of time we should assume someone will live.

As noted earlier, the spending needs of a surviving spouse are likely different than that of the couple. Taxes may go up with the shift from married-filing-jointly to single tax rates. Some expenses will go down. Other expenses could go up or new expenses could appear. A full analysis of mortality risk would include accounting for expected changes in spending after each spouse's death. Fortunately, by including mortality-adjusted income and spending in a plan, advisors can leverage planning for these changes.

Here are some examples.

Planning Case A: After analyzing expected spending needs, an advisor wants to plan for Mary to spend $1,000/month less if John dies, but for John's spending to continue without a change if Mary dies. The recommended spending that accommodates these expectations would not be $8,700 per month but $8,950 (changing to $7,950 when John passes, but staying the same if Mary died).

Planning Case B: John and Mary's advisor expects Mary's spending to stay the same if John dies, but for John's spending to go up by $1,000 per month if Mary dies. In this case, the advisor would recommend spending $8,000/month (changing to $9,000 if John were to survive Mary).

That these differences are roughly symmetrical is an accident. As a widower, John would keep his pension, but the chances he'll find himself a widower are also lower than the chances Mary will be a widow. In a different plan with larger differences in age or health or different sets of mortality-affected income, we might see much larger mortality effects.

How advisors communicate a plan dealing with mortality risk may differ. For some clients, the conversation could include an amount of 'showing your work' by sharing graphs like those above, but for many clients this could be confusing, making it more appropriate to simply discuss mortality risk and how the plan accounts for it.

For example, some advisors might approach the conversation with a presentation along these lines:

We built a 30-year plan, which puts you both at the ripe old age of 95. But, if one of you passes away, Social Security and pension benefits change. We don't know how long anyone will live, and we can't simply assume neither of you will ever have to deal with those decreased benefits. That would be foolish and would probably hurt the financial wellbeing of the surviving spouse.

Our recommendation takes into account mortality risk by spending a bit less from your portfolio now so that we can make up for the loss of Social Security and pension income if one of you passes away.

Customizing Mortality Assumptions

While in this example we used mortality assumptions for a 65-year-old male and 65-year-old female, the actual effects of using mortality adjustments would depend on the couple. Advisors could further fine-tune plans by basing mortality adjustments not on actual age but on a pseudo-age that reflects higher- or lower-than-expected mortality. For example, an advisor could treat a 65-year-old male with a history of heart disease in the family as being 70 for the purposes of mortality risk planning. This is similar in spirit to how insurance companies 'rate' the insured for life insurance.

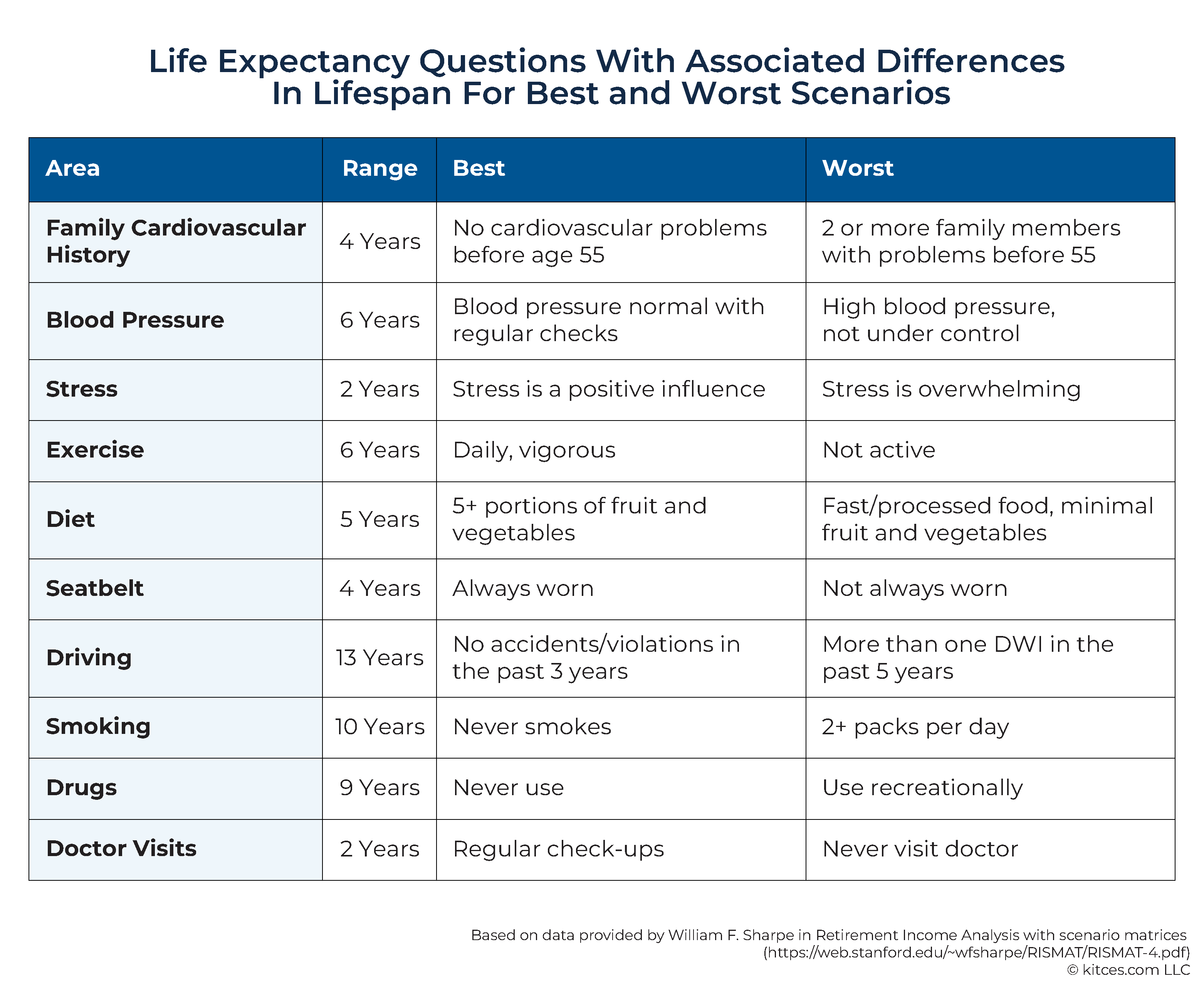

Determining appropriate adjustments of this sort would require specialized consulting with clients. However, the following table, reproduced (with slight wording changes) from Sharpe 2019, shows areas that can affect life expectancy. "Range" in this table is the difference in life expectancy between someone with the best and worst characteristics for that area, holding all else constant. (Improvements or reductions in life expectancy wouldn't necessarily be additive across areas.)

There are times, such as when someone has a terminal medical diagnosis, when it may be appropriate to assume one spouse will not live past a certain date not far in the future. However, in the absence of these special situations, using mortality-adjusted income is a better solution.

Ways To Optimize Planning For Longevity

There are many more nuances an advisor could address in planning for mortality risk, but we'll now move on to suggest ways that planning for longevity risk can be improved.

Use Longevity Risk Tolerance To Determine Plan Length

In the earlier example, we used a 30-year plan. But truthfully, this was just a number that felt round and conservative. Unfortunately, this shoot-from-the-hip approach is probably not uncommon. In 2020, David Blanchett, head of retirement research for Morningstar's Investment Management group, reported that, in over 31,000 financial plans he examined, projected age at death was a nice round age 90 in 70% of plans and 95 in 20% of plans.

A more rigorous approach to arriving at a plan length would use actual longevity expectations for clients based on their age, sex, and health status. For example, all else being equal, we would want to see the following types of differences in plan length.

- A plan should be longer for a female/female couple (compared to a male/female couple) and shorter for a male/male couple.

- Plan length should be different for a male/female couple of age 65/65, age 60/65, and age 65/60.

- Plan length should be lower if a client has worse-than-average health and higher if they have better-than-average health.

- Plan length should be shorter for an individual than for a couple that includes that individual.

If a retirement planning process doesn't deliver on expectations like these, then what is plan length – one of the most important assumptions in a plan – actually based on? Blanchett's findings suggest many advisors depend on planning software defaults (which, understandably, are round numbers). Since these defaults are fairly conservative and advisors want to decrease longevity risk, this is not unreasonable. But, even beyond the unintentional increase in mortality risk these older age assumptions can cause, wouldn't a client or a regulator expect an actual process for determining plan length? Such a process would at least consider clients' actual ages and other factors that affect longevity expectations.

Luckily, as with mortality risk, actuarial science gives us excellent tools for determining customized plan lengths. Longevity expectations differ markedly by affluence. For example, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report that life expectancy at 50 for those born in 1960 was 5.4 years longer for those in the top 20% of income earners than for those in the median group (the third quintile).

Assuming that clients of financial advisors tend to be in these higher-earning populations, in the software my company produces, we use mortality tables and improvement scales for retirement plan participants rather than general-population statistics. This helps us guard against underestimating longevity. Advisors who work with a different population may wish to use different mortality tables.

How would a financial advisor use actuarial data for longevity planning? The basic process takes three steps:

- Find a range of how long clients could live at different longevity risk levels.

- Pick a plan length from these options that matches the clients' longevity risk tolerance or expectations about their longevity.

- Update plan length regularly to reflect how life expectancy is changing as clients age.

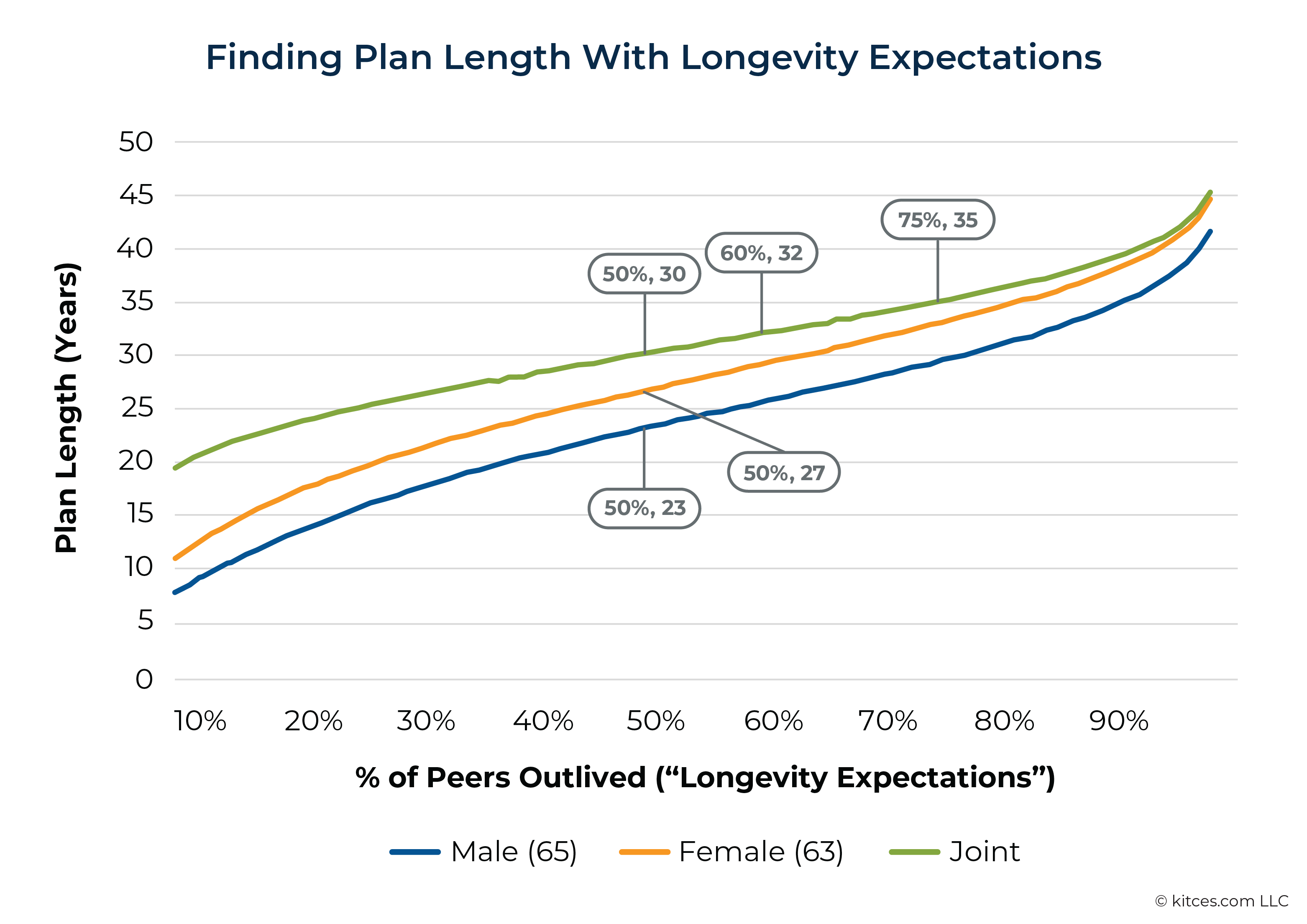

The graph below shows plan length ranges for a male/female couple of different ages – 65 (male) and 63 (female). Just like joint life expectancy, which conveys the expected length of time that at least 1 person in a couple will live, joint plan length for a couple is always higher than for 1 person in the couple.

50% of 65-year-old males will live 23 or more years. 50% of 63-year-old females will make it 27 or more years. And there is a 50% chance that at least 1 of the 2 in a couple lives 30 or more years.

This graph arranges plan length according to "Longevity Expectations", which reflects how long-lived someone thinks they will be. The higher the percentage score, the more of that person's peers they expect to outlive. If this couple believes they are average, they would adopt a 30-year plan. They would adopt a 35-year plan if they assume at least one of them will outlive 75% of their peers.

Update Plan Length Over Time

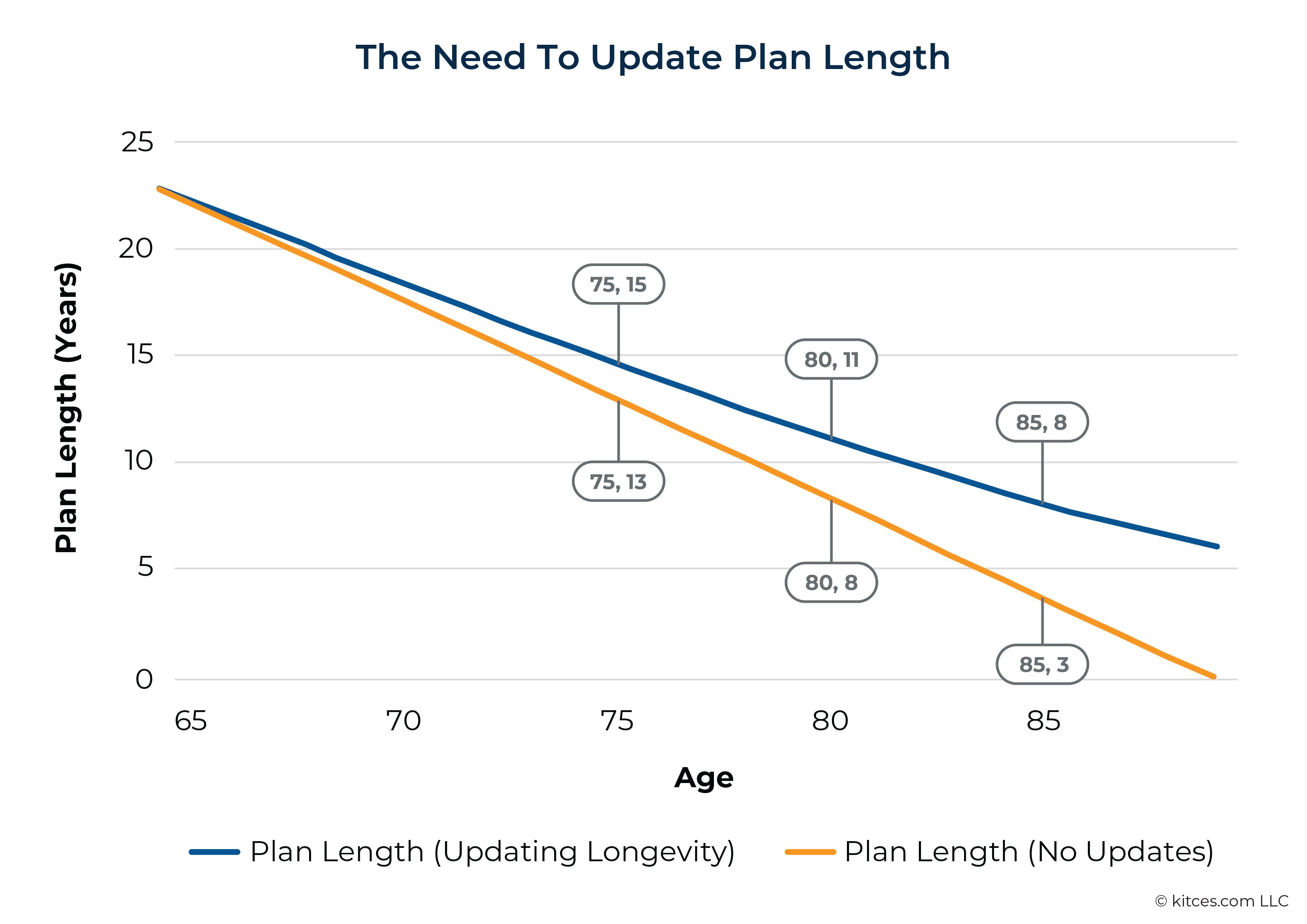

Step 7 in CFP Board's Financial Planning Process is to Monitor and Update the plan. Just as it is important to have a method for selecting plan length, it is also important to update plan length over time as clients age. Failing to do so fails to keep up with longevity risk.

Let's say an advisor is planning for Jim, a 65-year-old man with average longevity expectations. At age 65, that would give Jim a 23-year plan (to age 88). 10 years later, Jim is 75. If the advisor hasn't updated the plan, it would now be 13 years long. But wait – longevity expectations are different for Jim now, at age 75, than they were at age 65. After all, he survived from 65 to 75. If longevity expectations are updated (keeping expectations about Jim's likelihood of outliving his peers now the same as they were), Jim would now have a 15-year plan (to age 90). 10 years later, at age 85, he would have an 8-year plan (to age 93). By living 20 years, Jim gained 5 years of life expectancy.

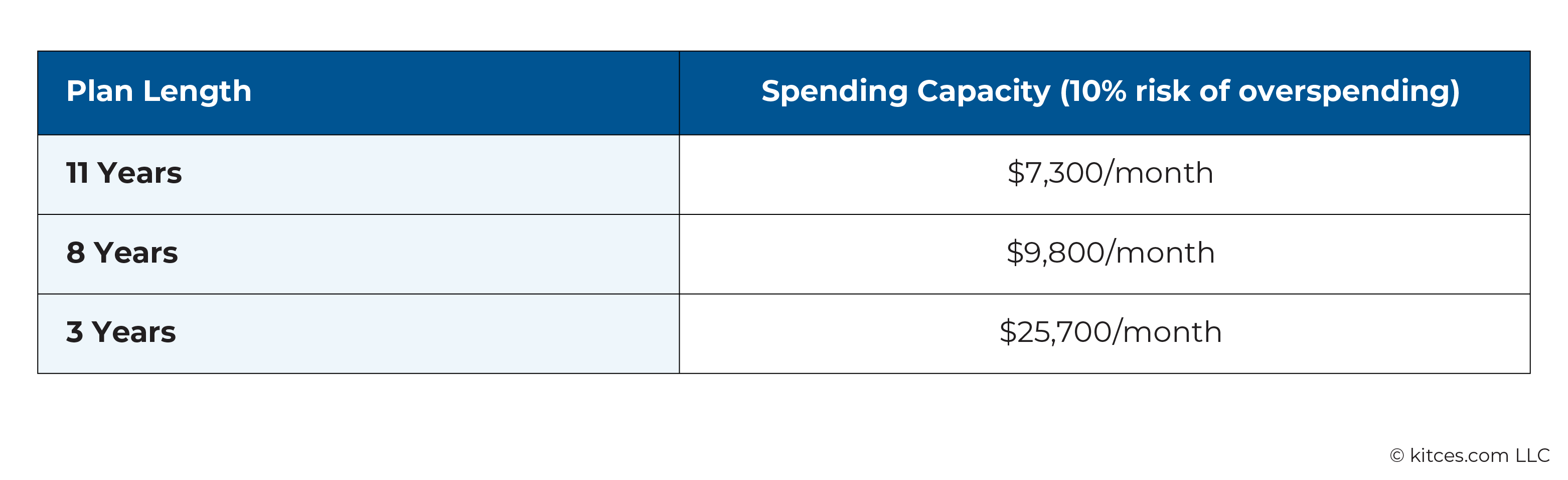

If expectations are not updated as Jim ages, his plan will be too short. This will increase his longevity risk. After all, there is a very large difference between planning for an 11-year plan, an 8-year plan, and a 3-year plan.

For instance, if Jim had a $1 million portfolio, using the same capital market assumptions as above, his spending capacity would vary greatly depending on plan length as shown below.

Getting plan length wrong at age 80 would mean planning for 8 years rather than 11. This would not give Jim the hoped-for 10% risk of overspending, but a 58% risk. Getting longevity wrong at age 85 (planning for 3 years instead of 8) would give him not a 10% risk of overspending, but a 100% risk!

Clearly, keeping longevity estimates up to date is not just a quibbling nicety. It's a vital part of monitoring and updating plans to provide good planning as people age.

An advisor may see this example and think, "Right! That's why I just plan to age 95 from the beginning." But while an advisor may feel that they have one shot to get plan length right and that their assumption should be very conservative, regularly updating the plan length in plan updates changes the situation. Using a process like the one shown above will continually push out the plan into the future. That means no one will ever 'catch up' to the end of their plan, and the plan will always consider how much longer (from that point) the client expects to need to fund their life.

This is a bit like being able to update a wager on a basketball game as the game progresses. As time goes on, you get more and more information about the way the game is going, so you're making better bets. With a retirement plan, if a client survives another year, the advisor just got more information about their possible longevity, and they get to push that longevity expectation out into the future. When plan length updates are incorporated into a larger process of monitoring and adjusting a plan, it becomes very powerful. While this may not mean plan lengths should be overly short, it should lower the pressure advisors may feel to extend initial plan lengths too far into the tails of expected lifetimes.

It's Time To Handle Longevity And Mortality Risk

When planning for investment returns and inflation, advisors routinely acknowledge and plan for uncertainty and risk. Unfortunately, when planning for mortality-affected income like Social Security and many pensions, most plans don't acknowledge the reality that we simply don't know when someone will die.

Unfortunately, assuming a long life in order to protect against longevity risk (outliving your money) can increase the risk that resources will be lacking upon the passing of the first spouse (mortality risk). To account for this risk, advisors can use expected mortality-adjusted income in the plan analysis to make sure they don't overstate how much a couple can afford to spend.

If we knew exactly how long someone was going to live, many parts of financial planning would become much easier. But, since we don't, it is important to make our best efforts to give advice that doesn't increase the risks faced by surviving spouses.

Leave a Reply