Executive Summary

"How much can I spend in retirement?" is perhaps the most fundamental question a client brings to their advisor. Answering it well requires a range of assumptions – from estimating average investment returns to understanding correlations across asset classes. These assumptions are rooted in Capital Market Assumptions (CMAs), which project how different assets might perform in the future. However, for many advisors, using these assumptions isn't always comfortable. Advisors want to help clients set a secure, reliable retirement plan, yet even the most comprehensive assumptions will inevitably deviate from reality at least to some degree. Which poses the question: How much error is acceptable, and how can advisors use these assumptions to set reasonable expectations for clients while maintaining their trust?

In this guest post, Justin Fitzpatrick, co-founder and CIO at Income Lab, explores how well CMAs reflect the realities clients will face, the influence these assumptions have on client advice, and how advisors can balance planning assumptions against the risks of long-term inaccuracies.

Ideally, retirement spending would align perfectly with a client's needs – neither too much nor too little. Yet, even with the most accurate CMAs, financial advice rarely aligns flawlessly with reality. Sequence of return risk, for example, means that even 2 identical clients retiring less than 18 months apart can experience wildly different sustainable spending levels. In some historical periods, the amount that a retiree could safely spend in retirement would have looked incredibly risky at the beginning of their retirement – and vice versa. Beyond market variables, clients bring their own behaviors and preferences into play. For instance, many retirees begin retirement by underspending to avoid depleting their resources – a choice that often diverges from the 'best guess' assumptions of CMAs and creates additional room for unexpected market conditions.

The good news is that CMAs can still provide a range of realistic spending limits, and, even better, most financial plans are not static one-and-done roadmaps. Advisors who actively monitor and adjust a client's plan as markets shift can mitigate the inherent uncertainty of CMAs, reducing the risk of overspending or underspending over time. Importantly, CMAs are most valuable when viewed as flexible tools rather than fixed forecasts – allowing advisors to refine assumptions as markets evolve and client needs change. This adaptive approach not only helps clients navigate uncertainties but also distinguishes advisors who are committed to continuous monitoring, enhancing client satisfaction and peace of mind.

Ultimately, the key point is that while 'perfect' CMAs may offer accurate predictions about general market conditions, they will still fall short of telling a client how much they can spend. Market fluctuations, sequence of returns, and personal spending behaviors all create unpredictable variations that CMAs cannot fully capture. However, by proactively monitoring and adjusting portfolio spending, advisors and clients can take advantage of the high points, guard against the lows, and, overall, ensure greater peace of mind!

Any type of financial planning requires assumptions – whether estimating average investment returns for time-value-of-money calculations or factoring in average returns, standard deviations, and correlations across asset classes for Monte Carlo simulations. Capital Market Assumptions (CMAs), which advisors use for many of the most important financial planning calculations, may come from software defaults, a firm's investment committee, or other sources. Yet, for many advisors, using these assumptions can come with feelings of trepidation. CMAs often prove to be wrong in retrospect, at least to some degree. And if the assumptions are wrong, won't the advice miss the mark?

For example, if an advisor assumes a 6% average expected return, but the client's actual average return over their lifetime is 5% (or even 3%!), how much would this affect the accuracy of the advice? What are the chances that this inaccurate estimate will lead the client to a major course correction at some point in the future? And how can an advisor use these assumptions while still having a good chance of delivering reasonable experiences to clients?

To answer these questions, it's important to look at how CMAs actually function in financial planning and how they are related to the advice an advisor gives. We can look at CMAs via 2 questions:

- How well do CMAs describe the world the client will live through?

- How do CMAs affect the advice given?

We'll address these questions by examining the influence of CMAs on retirement income planning. While question 1 is interesting, it turns out that it's not the most important question for delivering great retirement advice. Only question 2 really matters for outcomes in the real world. This distinction should give advisors some comfort that CMAs don't have to be fully accurate predictions.

We'll see here that even 'perfectly accurate' CMAs don't lead to perfect advice. This means that no matter the accuracy of an advisor's CMAs, advice on actual retirement spending levels will almost certainly be wrong, at least to some extent. This weakness of CMAs for predicting the correct level of retirement spending is another argument for the use of adjustment-based ongoing planning: Accurate CMAs can't produce accurate spending advice, so ongoing adjustments are needed to incorporate new information as time goes on and to keep retirement clients on track.

Capital Market Assumptions Are Not Everything

Imagine having a crystal ball when creating a retirement income plan. It reveals, with perfect accuracy, the average returns and standard deviation of returns your client will experience over the length of their plan. That might feel like an incredible gift. With those statistics, it should be easy to give clients perfect advice on retirement spending, right? Unfortunately, it's not.

Since 1871, the average returns and standard deviation of returns (for a 60% stock/40% bond portfolio) for each 30-year period explained only 43% of the variation in available spending. (To put it technically, the R2 value of the linear regression between historically perfect CMAs and the maximum inflation-adjusted systematic withdrawals that someone could have maintained through that period is just 0.43.) That's not nothing, but it's also not nearly enough. Even with perfect values to plug into the capital market assumptions of your financial planning software, you still couldn't answer the question, "How much can I spend in retirement?" with perfect accuracy.

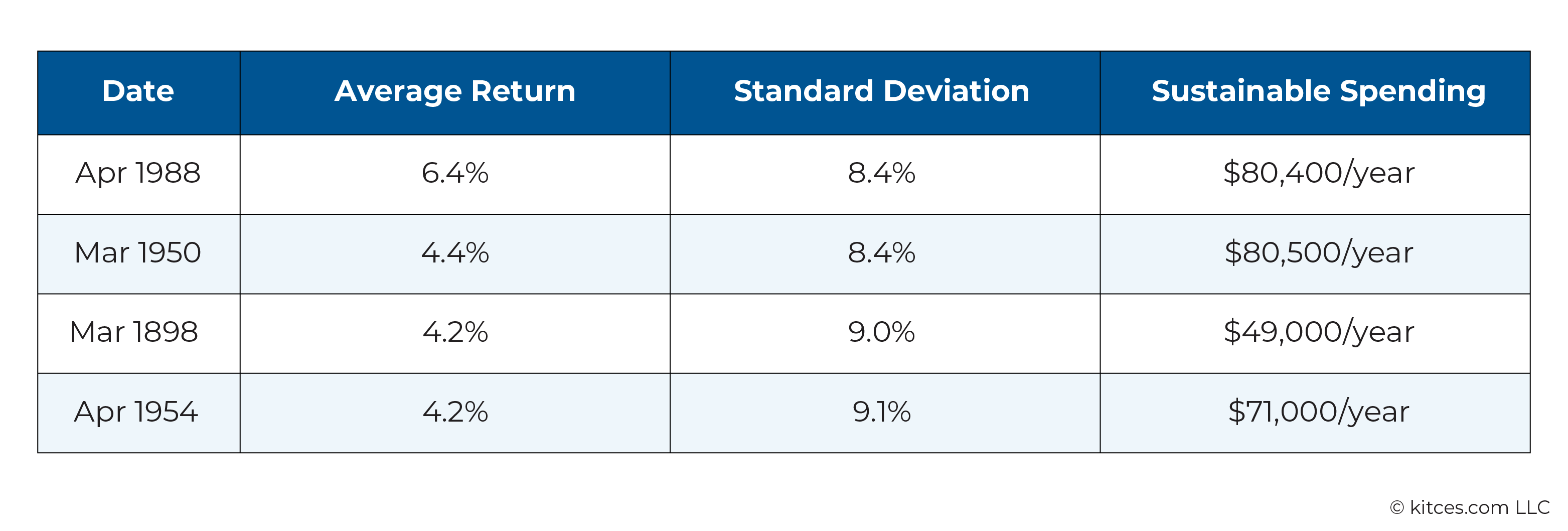

A few historical examples help show how even perfectly accurate CMAs still leave a lot of variability in spending unexplained. A client who retired in April 1988 and knew that they'd achieve real returns of over 6.4% annually, with an 8.4% standard deviation, could have spent $80,400 per year from a $1 million 60% stock/40% bond portfolio for 30 years. Yet, a similar retiree in March 1950, with an average return that was 2% lower (4.4%) but with the same 8.4% standard deviation, could have sustained almost exactly the same spending level. In other words, these periods with very different average returns would have supported the same retirement spending.

A second pair of retirement dates shows the reverse: The returns in the 30 years following March 1898 and April 1954 had almost identical average real returns (4.2%) and standard deviations (9% and 9.1%, respectively), and yet the sequence of returns from 1898 would only have supported $49,000/year in inflation-adjusted withdrawals, while the returns following 1954 supported over $71,000 in annual withdrawals – about 45% more.

Advisors familiar with retirement planning will recognize the explanation for this puzzle: sequence of returns risk. It's not enough to know average returns or their variability; the actual order in which returns occur can greatly affect spending sustainability.

How Does Predicted Risk Line Up With Actual Experience?

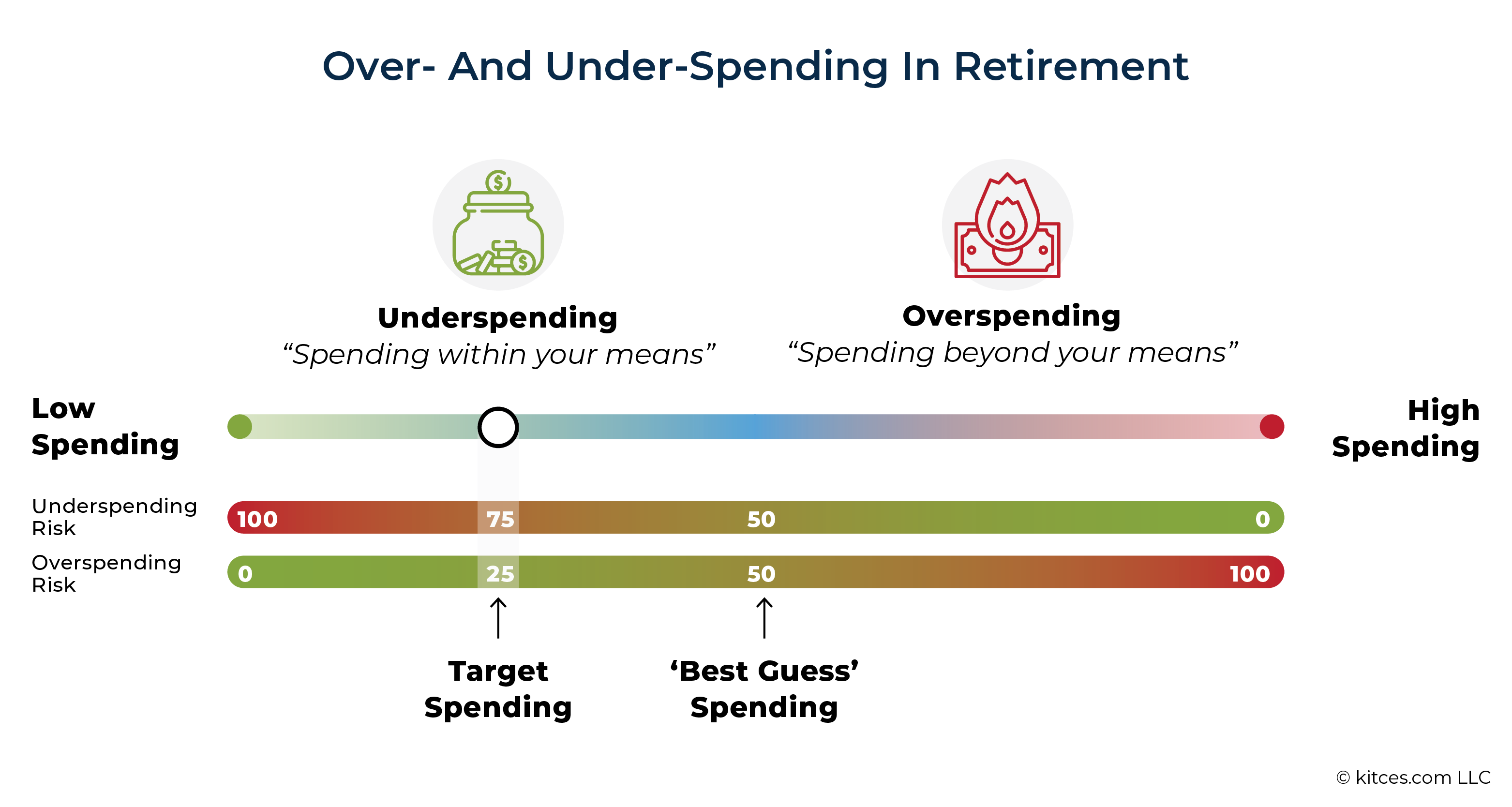

Ideally, in retirement, someone would neither spend too little (which could lead to regret over foregone experiences with friends and family) nor too much (which could lead to spending cuts before the end of the plan). These 2 risks – the 'risk of underspending' and the 'risk of overspending' – are core to retirement income planning.

Advisors typically use Capital Market Assumptions (CMAs) to create hypothetical sequences of returns (and, in some software, sequences of inflation). With a range of these hypothetical scenarios, an advisor can estimate the likelihood of overspending or underspending at any spending level. For example, spending $51,000 per year might have an 80% risk of underspending and 20% risk of overspending, but at $65,000 per year, that risk could be 50%/50%. An advisor would use these estimates to give spending advice, matching the right balance of overspending and underspending risk to client preferences.

From each point in history, we know what clients could have sustainably spent over the next 30 years. That's because from the vantage point of today, we know not only the average returns for each period but also the actual return and inflation sequences. This lets us ask what risk estimate our hypothetical advisor with perfect CMAs would have given each historically sustainable spending level – before knowing it would actually be correct.

For example, the table above shows that in 1988, this advisor would have assumed 6.4% average annual returns over the next 30 years. What risk would this advisor have estimated a client would take on by withdrawing $80,400/year (the actual maximum this person could have taken, given the actual sequence of return from that point) from their portfolio? Similarly, in 1950, what risk would this advisor have assigned to taking $80,500/year while assuming 4.4% average annual returns?

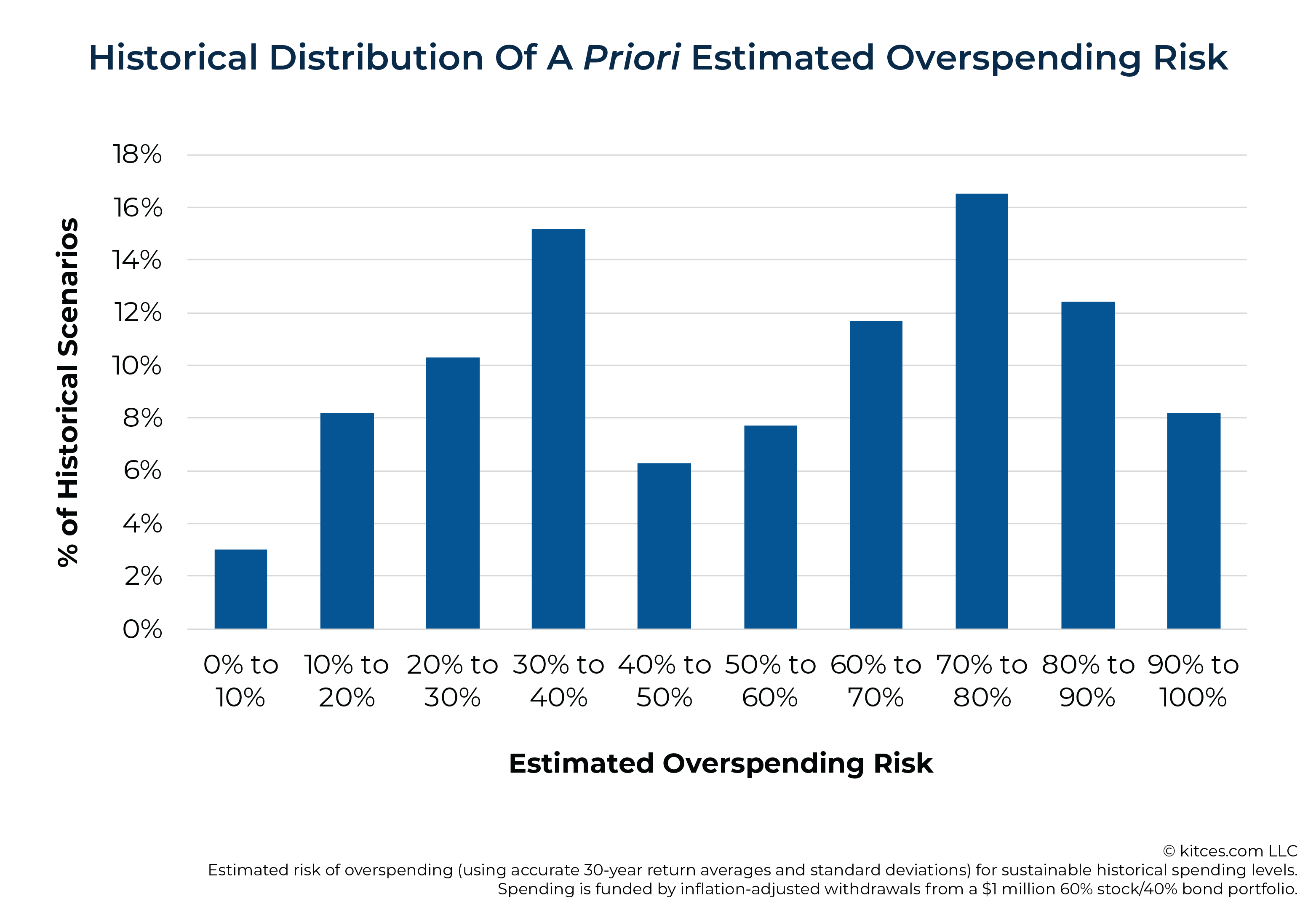

When we ask this question for all historical periods, we see a huge range of answers. Some historically sustainable spending levels had very low a priori estimated risk, some medium, and some very high.

For some periods, even with perfect capital market assumptions, the actual amount someone could have spent would have appeared to be incredibly risky at the beginning of retirement. In those scenarios, an advisor would likely have recommended a spending level that was, in retrospect, too low. Conversely, there are periods where a spending level that ultimately proved sustainable would have been predicted to have extremely low risk. In those scenarios, an advisor might have counseled spending that, in retrospect, was too high. And there are many scenarios in the middle.

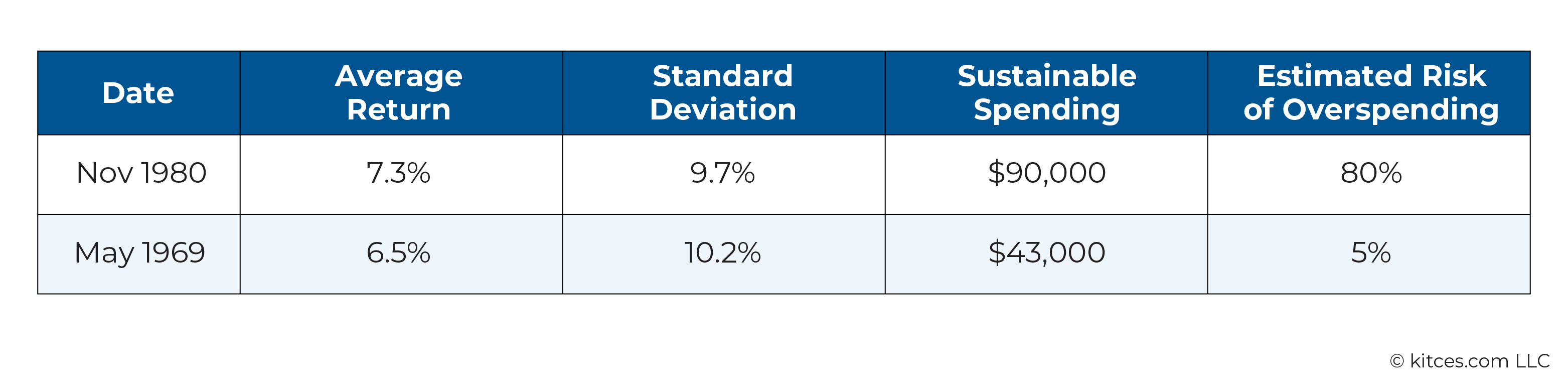

For example, let's consider November 1980. We know now that real returns over the next 30 years would have averaged 7.3%, with a standard deviation of 9.7%. With the benefit of hindsight, we know that someone retiring then could have sustainably spent over $90,000 per year from a $1 million portfolio. However, based on accurate CMAs alone, this spending level would have had a predicted 80% risk of overspending ahead of time. This would have seemed outrageously risky at the time, and an advisor would likely have recommended a far lower initial spending level. However, any lower spending level would have been underspending the true resources the family would have found themselves with.

By contrast, in May of 1969, the next 30 years' returns averaged 6.5% with a standard deviation of 10.2%. However, the actual sustainable spending level from that point, roughly $43,000 per year, had only a 5% estimated chance of overspending. Any higher recommended spending level would have been unsustainable and ultimately led to downward spending adjustments.

Given how little power even perfectly accurate CMAs seem to have for predicting the actual spending someone could have in the future, it's reasonable to ask how much CMAs really matter. Do accurate CMAs add anything to the planning process?

Yes, they do. Accurate CMAs can paint an accurate picture of the economic environment clients will live through (which answers question 1 earlier), but only at the highest level: With accurate CMAs, the actual maximum sustainable spending level for each historical period was never greater than the highest predicted possible spending level, nor below the lowest. In other words, 'perfect foresight' CMAs did set an accurate range on possible spending. The lowest risk of overspending that would have been predicted with perfect CMAs was 4%. The highest was 99%.

Furthermore, the distribution of actual sustainable spending was roughly in line with what we might expect:

- 89% of historical spending levels fell within the middle 80% of the distribution predicted by accurate CMAs.

- 68% were within the middle 60%, and so on.

That slight tightening of the distribution in reality is likely due to the tendency of Monte Carlo simulations to overstate things on the tails of the distribution. But since these spending distributions are directly related to estimates of overspending and underspending risk, this is a major virtue of accurate CMAs.

In summary, accurate CMAs do the following:

- Set accurate 'bookends' or limits on possible spending by defining realistic high and low limits; and

- Set roughly accurate estimates of spending risk, offering insight into potential overspending and underspending.

However, perfectly accurate CMAs cannot perfectly predict future spending levels. They predict a cloud of possibilities, not a single spending level. It's true that certain ways of modeling the world may be better than others, but we cannot reasonably expect to get fully accurate predictions of future spending levels. There is no way to know ahead of time whether someone is about to enter a period that will support a spending level in the middle or in the tails of the estimated range of possible spending.

How Far Off Can CMAs Be?

We just saw that perfectly accurate CMAs do provide a reliable framework of setting 'bookends' to the range of retirement spending levels someone might be able to sustain, along with a reasonable estimate of the overspending and underspending risks for each spending level. But what about inaccurate CMAs? After all, except in cases of extremely good luck, we would expect all CMAs to be inaccurate to at least some degree. Specifically, the concern may be that CMAs are too optimistic. No advisor wants to overestimate (overpromise) and under-deliver. So, how much 'margin for error' does an advisor have in setting CMAs? Can return estimates be too high without resulting in deeply flawed advice?

Here we shift from addressing the first question above (Do CMAs paint an accurate picture of the world?) to the second: How do CMAs affect the advice given? To answer this, we need to know what risk level an advisor might target when giving retirement spending advice. In my company's software, Income Lab, we typically see plans that target between 0% and 25% risk of overspending at the beginning of retirement. That is, advisors and clients typically prefer to begin retirement with a reasonably large 'risk buffer' that aims for a relatively low chance of overspending. Clients generally stay well within the 'underspending zone' so that things can get significantly worse before they would have to make a downward adjustment in spending or some other plan change. By contrast, a spending level with a higher estimated risk of overspending than underspending would fall in the 'overspending zone', meaning that someone at this level is spending beyond their means.

To know an advisor's margin for error in setting CMAs, we need to establish the target risk level for their initial retirement income advice. In this example, we'll use a fairly conservative target of a 10% risk of overspending (or a 90% risk of underspending) and ask how much overestimation of average returns would cause an advisor to inadvertently counsel overspending.

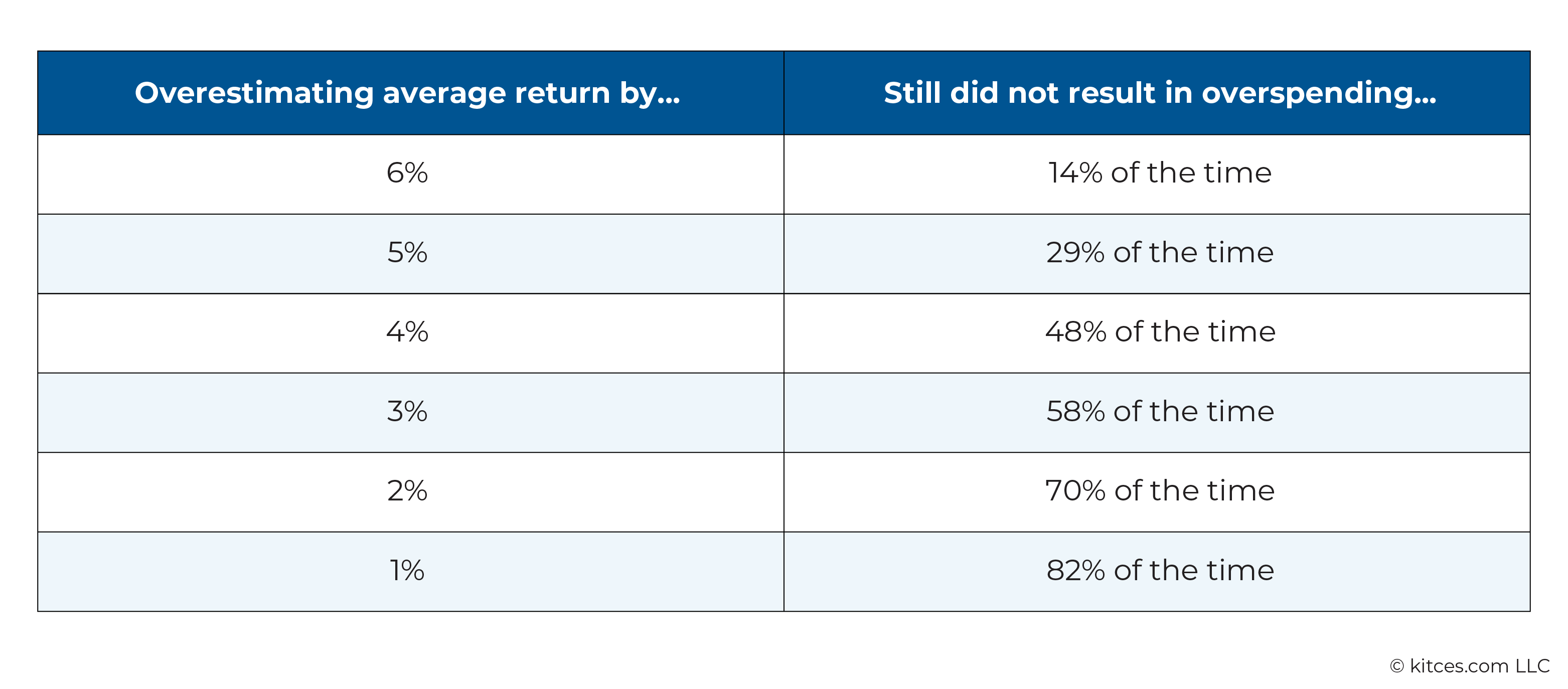

For this analysis, we'll set the standard deviation assumption of 10.7% – the all-time historical average for this portfolio – rather than assume the advisor has an accurate estimate of the standard deviation for each period. As the table below shows, large margins for error have historically been fairly common.

Nerd Note:

The absolute margin for error for CMAs would differ depending on the target portfolio. The higher the actual average return and standard deviation, the higher the margin for error in absolute terms. (Here, we're looking at a 60%/40% stock/bond portfolio with an all-time historical average real return of 6% and standard deviation of 10.7%.)

Roughly half the time, the average return assumption could have been off by 4% without pushing the proposed spending into the overspending zone. 70% of the time the average return assumption could have been off by 2% or more without resulting in overspending. This finding should be heartening to those worried that their return assumption may be too high. It also suggests that striving for not just accurate but extremely precise CMAs may not result in noticeably better retirement experiences for clients. The difference between a 5.0% average return and a 5.1% return is likely negligible and may not mean much in the real world.

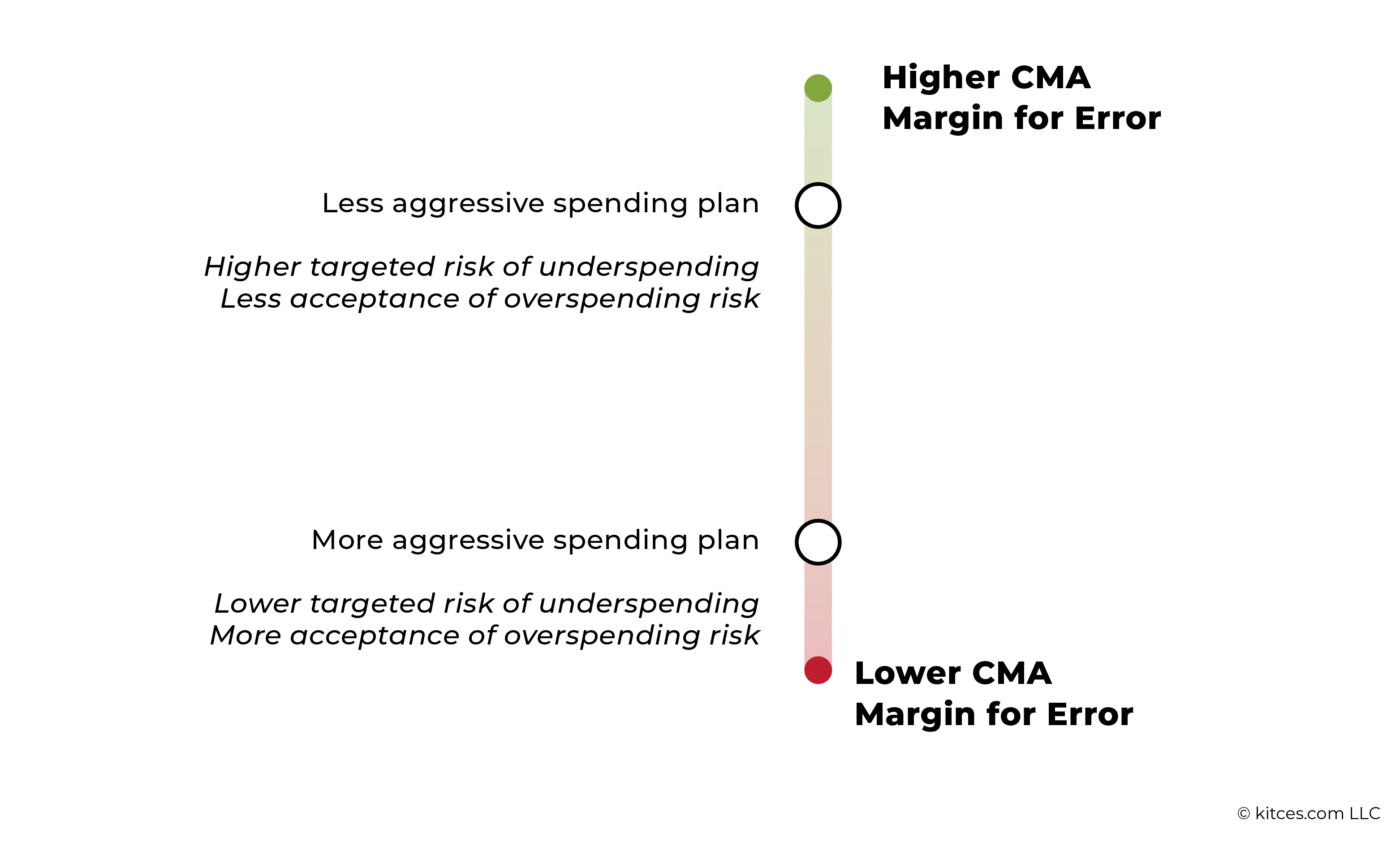

While there's a lot of margin for error historically, it's important to note that the margin decreases with less conservative spending plans. For example, a plan targeting a 40% risk of overspending/60% risk of underspending allows for less margin than one targeting a 20%/80% or 1%/99% risk split. This means that those who are more concerned about inaccurate CMAs may wish to favor less aggressive spending plans. It also means that advisors who both reduce CMAs to avoid overstating future returns and reduce spending may be implementing an overly cautious 'belt and suspenders' approach.

Unfortunately, even when targeting a spending level deep in the underspending zone, there are historical scenarios when using a return assumption that is even 1% too high would have resulted in inadvertently advising clients to overspend. And of course, for some of the worst sequences of return in history, targeting a 10% risk of overspending even without overestimating future returns would have resulted in overspending. While this outcome isn't common, it remains a concern. So, what's an advisor to do?

When CMAs Are Not Enough: Plan For Adjustments

CMAs, even perfectly accurate ones, can't predict exactly how much someone will be able to spend in retirement. But clients still want answers to the basic question, "How much can I afford to spend?" The key to addressing this dilemma is to recognize that retirement income planning doesn't require a one-time-only 'set it and forget it' decision. Instead, the ongoing process of guiding someone through retirement involves revisiting this question as the years – and even decades – progress.

When we structure retirement planning as ongoing guidance, assuming that clients are willing and able to make adjustments, the predictive weakness of CMAs becomes less problematic. Structuring retirement income planning in this way involves the following steps:

- Build a full picture of client resources, needs, and preferences.

- Using a reasonable model of the world, including CMAs, estimate a range of spending levels that may be possible for the client(s) today.

- Find an optimal spending level within this range that aligns with client risk preferences, balancing their ability and willingness to take on the risk of future cuts in income with their desire to spend and live life well. This becomes the answer to the question, "How much can I spend?" Advisors who are especially concerned that their return assumptions may be too high can target a spending level with a lower risk of overspending.

- Set 'guardrails' to signal when clients can spend more (because their risk of underspending is too high) or less (because their risk of overspending is too high). These guardrails will address the question, "Should I adjust my plan?"

- Update and monitor the plan regularly and adjust spending or other parts of the plan as needed to keep risk in a reasonable range.

Testing this approach shows that it results in very reasonable income experiences, even when CMAs are neither perfectly accurate nor perfectly predictive. When we choose a spending level in step 3 that's in the middle of the 'underspending zone', we find that, even in some of the worst economic periods in history, plans required only minor and temporary adjustments.

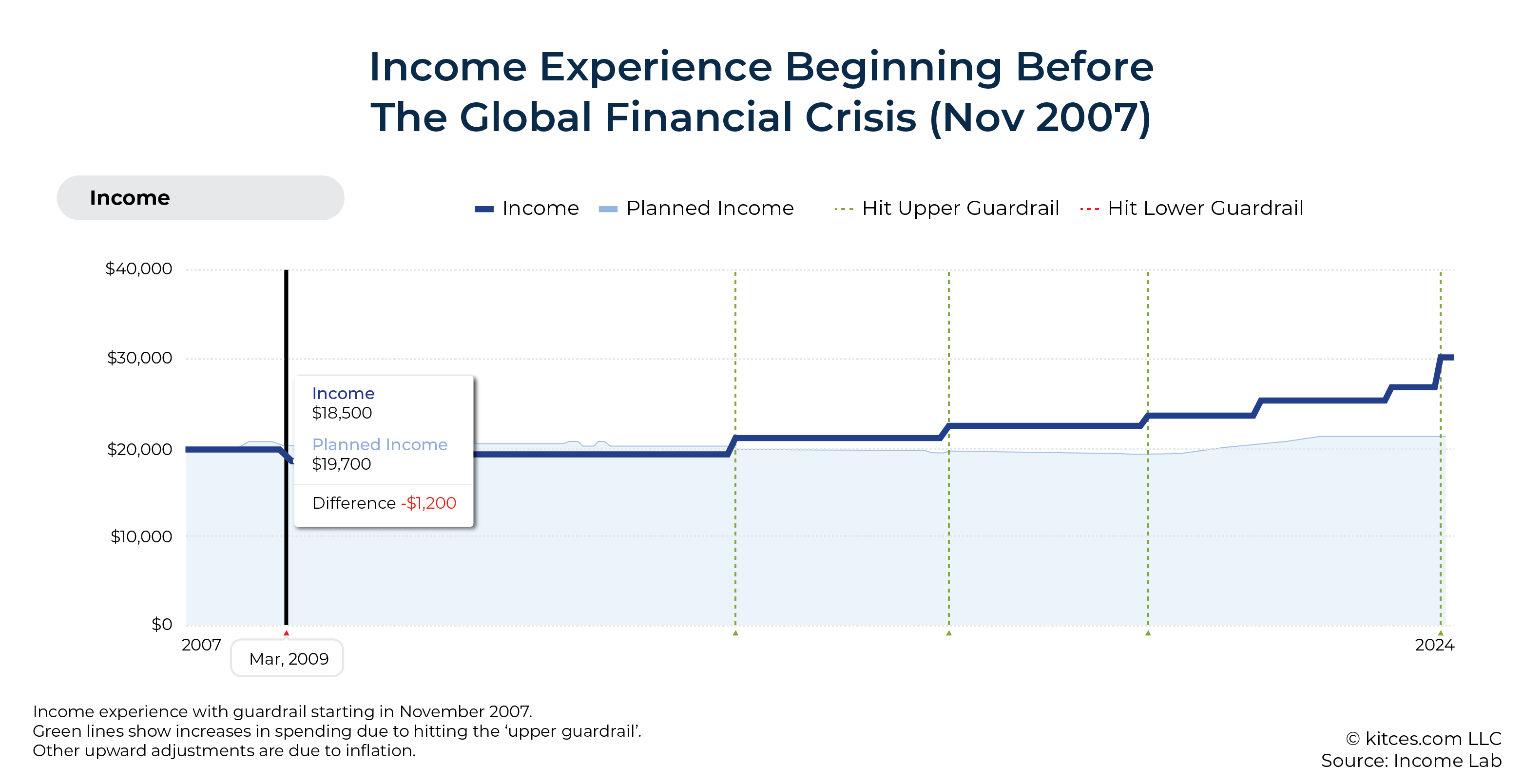

For example, consider a realistic and complex plan that includes income from portfolio withdrawals, Social Security, a pension, rental properties, and other sources, targeting a 20% risk of overspending. If this plan had started in November 2007, it would have hit its lower guardrail in March 2009 and prompted a 6% spending adjustment downward. However, after a small inflation adjustment in June 2011, the plan was only $800 per month below its originally expected spending level.

By March 2015, the plan had improved enough that the plan hit its upper guardrail, bringing income $1400/month higher than originally planned. By August 2024, because of great investment returns, monthly income exceeded $30,000.

This is just one example from one time period. More aggressive spending plans might require more frequent and possibly larger downward adjustments, while less aggressive plans tend to create smoother income experiences. But we see similar patterns across plans and historical time periods: Even with CMAs that are never fully accurate, adjustment-based planning is able to keep plans on track.

Of course, the more accurate the CMAs, the better. Unrealistic assumptions – such as expecting a 25% average annual return – will likely lead to poor outcomes, even with adjustments. However, this approach of regularly updating plans and adjusting behavior over time makes up for many of the inherent shortcomings of CMAs alone.

There's nothing wrong with striving for better assumptions and a better model of the world, but since no model will ever be perfect, having a plan that incorporates new data as it becomes available over the years – and adjusts plans and spending accordingly – is vital for providing good retirement spending advice!