Executive Summary

The standard advice in saving for retirement is rather straightforward: save as much as you can, starting as early as you can, to maximize the amount of your savings and how long it has to grow. The more you can get into the retirement account, and the longer that you can let it compound, the more affordable it will be to retire.

However, the reality is that trying to increase savings actually has a dual positive effect on reaching retirement: not only does it mean there’s more in the account to grow, but saving more reduces your retirement savings need. The reason, simply put, is that for any given level of income, the more you save, the less you’re spending to live on – and if you don’t spend as much to maintain your lifestyle, you don’t need as much saved up to replace it!

In fact, the impact of increased savings (and the associated reduction in spending) can actually go a long way to help bridge the gap for retirement, especially for late-stage savers. On the other hand, for those who are still younger, strategies that help to maintain (but not substantially increase lifestyle), and let future raises be directed towards savings instead, can dramatically accelerate the path towards early retirement as well by controlling the retirement savings need. In the extreme, highly frugal living allows for extreme early retirement, precisely because it facilitates both substantial savings, and doesn't necessitate much to achieve financial independence given that very frugality.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that the reason big savers who live modestly are more able to retire is not just because of the savings itself, but the fact that a moderate spending lifestyle can dramatically reduce retirement savings needs in the first place!

The Benefit Of Saving Early And Often

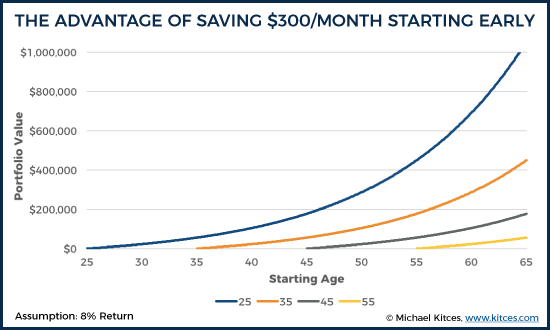

Accumulating retirement savings is a combination of how much you save, the rate at which it grows, and how long you have to save and grow the account. In the early years it’s all about the amount you contribute, while in the later years the growth rate itself is the primary driver, but in the end, the more you can save and the longer it can grow, the more opportunity there is for compounding to work its magic.

In fact, given the sheer power of compounding in the later years (where the growth just compounds more growth), it’s possible to accumulate a whopping $1,000,000 account balance for retirement by doing nothing more than “just” saving about $300/month for 40 years from age 25 to 65 (and letting the growth compound in equities at an 8% average annual return).

With a shorter time horizon to compound, though, that $300/month never compounds nearly as far… as if the saver doesn’t start until age 35, the account only grows to $450,000, and if they start at age 45 it’s just $178,000, and starting at age 55 yields a final balance of only $56,000.

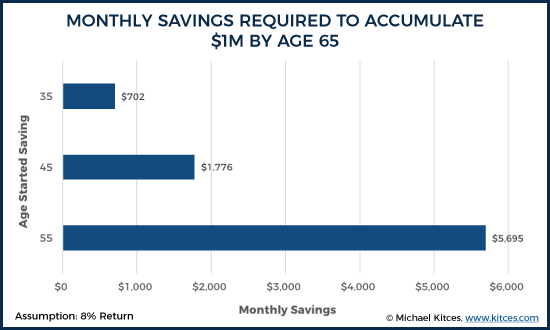

Of course, the “later stage” saver who wants to catch up can bridge the gap by saving more, although the shorter the time horizon, the more that the raw savings itself must bear the load (as there isn’t enough time for material compounding of returns).

As a result, if the goal is to get “back on track” to the original $1,000,000 accumulation goal at age 65, a 35-year-old must save $702/month, a 45-year-old must save $1,776/month, and a 55-year-old who only has a decade needs to save a whopping $5,695/month to get caught up!

Needed Retirement Savings And The Double-Edged Impact Of Saving More

Notably, how much a prospective retiree saves doesn’t impact just their savings. Since you can only save what you don’t spend, for any given level of income, those who save more will by definition also be spending less. Which is important, because it means they won’t necessarily need to save as much to maintain that (reduced spending) lifestyle in retirement!

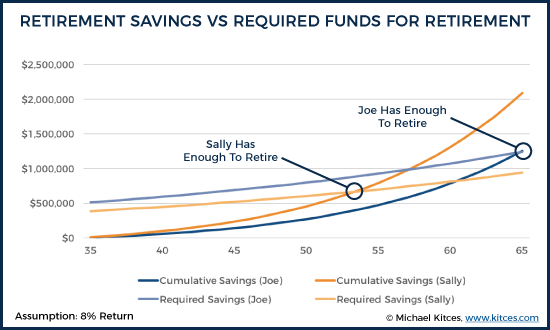

For instance, Joe and Sally both make $65,000/year at age 35, take home about $50,000 after taxes, and want to start saving for retirement now.

If Joe starts saving 15% of his income (and his income grows at 3%/year), then by age 65, he can save over $1.25M (which on top of projected $22,000/year of Social Security benefits, should be able to maintain his lifestyle at a 4% safe withdrawal rate).

Sally, on the other hand, can save 25% of her income (also growing at 3%/year), then by age 65 her account balance is up to nearly $2.1M instead. In fact, she had already reached Joe’s retirement account balance of $1.25M by the time she was just 60!

But the key distinction is that because Sally is saving more, she’s living on less, which means she doesn’t need as much as Joe to retire in the first place (at least to maintain that same lifestyle). Given that Sally is living on only $37,500/year instead of $42,500, she could have actually retired by age 54 instead – because her retirement savings need never climbed as high as Joe's in the first place!

In other words, the key change that happened when Sally decided to save more is that she both added more to the account for future growth, and reduced her retirement savings need in the first place! Which means it not only takes her fewer takes to achieve the same amount of savings, but she can retire even earlier because she doesn't need as much in the first place!

(Michael's Note: Technically, Sally would likely need to retire a few years later, as this graphic doesn't explicitly account for the additional savings Sally would need for the first ~10 years until her Social Security benefits began. Nonetheless, given her compounding account balance, this would likely only delay her retirement to approximately age 56, instead of 54.)

Cutting Spending And Managing Lifestyle Creep To Turbo Charge Retirement Savings

The fact that cutting spending to increase savings both adds to savings and reduces the retirement savings need is crucial for those trying to bridge the gap to retirement. Because it means that even just moderate spending changes can actually have an outsized double-impact.

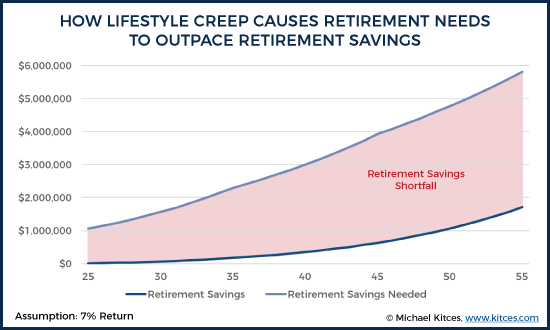

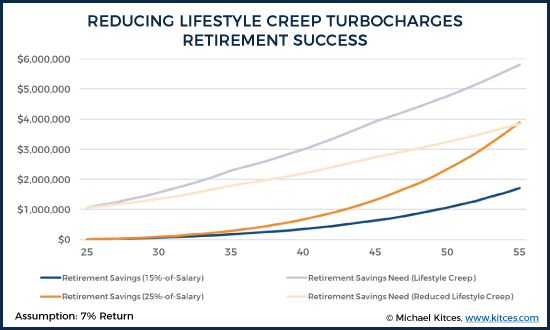

Conversely, though, this is also why managing lifestyle creep – where lifestyle expenses creep higher over time as earnings grow – is so important, especially in the early career years when earnings tend to grow at a real rate above inflation. Otherwise, the rising lifestyle that often goes hand-in-hand with rising income means you can actually get further behind on retirement, even as you save!

For instance, Charlie is a 25-year-old who’s gotten a good job paying $50,000/year at age 25. And because he maintains a moderate lifestyle, he’s able to save 15% of his income. Over the decade, his earnings grow at 5%/year above inflation (i.e., 5%/year in real earnings growth), which slows to “just” 2.5%/year of real earnings growth over the subsequent decade, and 1%/year in the decade thereafter. If we assume that Charlie will try to replace his then-current spending (everything he’s not already saving) at a 4% safe withdrawal rate, and grows his account balance by 7%/year in a moderate growth portfolio to keep pace with 3%/year inflation, then it turns out that Charlie is actually further from retirement at age 55 than he was at age 25! In other words, the retirement savings gap actually gets worse as Charlie's rising lifestyle increases his retirement savings need faster than he can actually save and grow his retirement assets!

Given these dynamics, the reality is that “managing the retirement savings need” (by managing lifestyle expenses) is just as important as managing retirement savings itself. Because otherwise, a rising income paired with a rising lifestyle means retirement gets further out of reach – even in situations where you’re saving a steady percentage of your rising income. On the other hand, the reality is that if the saver can just maintain a consistent lifestyle, and allocate the majority of every raise to savings – thereby limiting how quickly the retirement savings need rises – it’s actually possible to retire much earlier!

For instance, continuing the prior example, assume that instead of saving 15% of his (rising) income every year, Charlie starts out saving 15% (or $7,500), but in future years he increases his savings by 50% of his annual raise. As a result, Charlie's lifestyle will still rise over time (given that he’s enjoying a real earning increase above inflation), but the slower increase in his lifestyle will slow how quickly his retirement savings need is rising, even as the growing savings turbocharges his retirement portfolio itself. The end result – instead of still being less than half way to his retirement savings at age 55, Charlie will have already retired by then!

In fact, the ability to manage lifestyle creep and live modestly is also a driving force in the success of the “extreme early retirement” movement, where savers try to save the overwhelming majority of their income. Because doing so simultaneously allows for substantial savings, and drastically reduces the retirement savings need. For example, a 30-year-old dual-income couple who earn $120,000/year but manages to live on just $30,000/year, and saves $70,000/year (after taxes) growing at 8%, could have enough money to retire at that inflation-adjusted $30,000/year by age 40 (again assuming a 4% safe withdrawal rate)! In other words, the couple could retire after just 10 years of working (akin to early retirement icons like Mr. Money Mustache).

Of course, not everyone will necessarily have the ability (or lifestyle inclination) to manage their expenses to that extent. Nonetheless, the fundamental point remains: that good savings habits not only help to accumulate for retirement but also amplify their impact by reducing the amount of the retirement need in the first place… and the two combined together can go a long way to quickly bridge a retirement savings gap!

So what do you think? When thinking about retirement savings, do you look only at the projected accumulation, or also the impact on the retirement savings need? Is it helpful to think about how retirement savings and retirement needs move in tandem with spending/savings changes? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

This is great! I have run a few spreadsheets for myself using this same methodology at the age of 27. You can also consider separating our discretionary and non discretionary expenses. In the case of the 30-year-old dual-income couple, they could be considered financially independent before the age of 40 if their non discretionary expenses were only a portion of the $30,000/year. The discretionary expenses could be paired with a ‘discretionary income’ like a side hussle for example. Then the couple go on vacations or spend other discretionary money only when they had voluntary discretionary income.

Nice article! It’s well known in the FIRE (financial independence retire early) community that you get the double benefit from savings as you indicate here. In addition, I’ve also shown in some posts that the power of saving is much stronger than investing for many years, until you have a large portfolio. I’ve been an aggressive investor and done well with my investments but when I calculate net worth gains over the years, 2/3 came directly from savings and only 1/3 from investments (15 year timeframe and an 8% compounded return on investments). By living well below your means, you can reach financial independence much earlier than many believe is possible.

Very good concept. I’m a big fan of living well within your means and saving as much as possible.

Great post. The biggest waste for most consumers are the big house, fancy cars followed by high cell phone bills and ridiculous cable charges. All told these can amount to a significant amount of discretionary expenses. I will also say that as one accumulates wealth financial advisor fees (say 1% of assets) become a huge drag on building net worth. Since this site is devoted to financial advisors I know there will be push back to this but one merely needs to read the blog of bason asset management to obtain an alternate perspective.

Wes, I agree on the waste on cars and houses and such. But don’t count yourself short on the fee comment. Not everybody needs a financial advisor…I see prospects that need to be put on Financial Advisor life support and those that I really have to dig to try to show some value. If your advisor is only providing investment advice, 1% might be high. If they are providing tax planning and compliance and keeping your financial plan current and making sure your insurance and estate needs are current, the 1% fee might generate much more $$ to you over and above the 1% fee and therefore be well justified.

A CPA/CFP is a killer combination!!

People shouldn’t be paying a percentage. Look for financial advice that is paid by the hour. Then the cost won’t increase in direct proportion to your account size. If you’re paying money managers for active management, you need to read some Warren Buffett or Larry Swedroe, and realize that you are probably getting negative alpha for those fees, and dump the active management. I have a well-diversified portfolio and average 0.15% in expenses.

I just retired (on 12/31/2016) after 33 years total full-time working following graduation (MSEE). I just turned 58. For the past 15 years I’ve been living on half my pay and socking away the other half–besides 401K, mainly paying off my mortgage, which I succeeded at just before I retired. You’re absolutely correct: I realized some time ago that besides building up the nest egg, just as important was to learn to live on less. It’s no problem now; my lifestyle won’t change that much (besides no commute now)! Thanks for your reassuring advice.

Exactly. I think for most the “millionaire next door” model is more viable. Higher savings and more frugal than usual, but not hugely so. By 56 let me consider retiring, so when ejected by corporate downsizing shortly after, no need to hit the panic button. If the job search busts, no problem, just retire and enjoy!

Wow, Kitces hit this one dead on! (As he normally does.) The only item he should have emphasized is that if you’re truly living the frugal lifestyle, then you should not work a day longer than needed. I only once bought a new car, I didn’t change wives like a jockey at the races, I paid-off my house early as I could, then socked-away savings, mine and my wife’s through deferred earnings from our paychecks. Still wound-up with substantial post-tax savings. We retired as soon as we wouldn’t be hit for “early retirement” at age 61 1/2. and took “leave without pay” for the last few months. Then the retirements started rolling-in, and we’re now 65+ and still we haven’t needed to touch our very large portfolios. And, we envision taking social security until age 70, since we don’t need “more” income now, we may as well take the extra 7-8% take we earn through deferring. Dang, retirement is great!

Kudos to those who responded. All seem to reasonable rational replies. I am so use to those who respond with a “yes but” reply listing the reasons why they could not save. I am gratified to read replies from those who do rather from those who whine.

This article is very well written. This is the reasoning I used through out my working years. I knew my retirement income would not need to be 80% of working income, as recommended by so many advisors because we were living on 60%. Drove used cars till they died and lived in modest home. Also no advisors taking a cut. All you need is a subscription to a good magazine like Money and a little common sense. My wife quit her job and raised the children. When they were older she went to work part time. One hundred percent of income went in to her 401K and I funded a spousal Roth IRA for her. I maxed my 401K and a Roth IRA every year for me. We retired at 62 are now 68 and as my daughter says “floating in money”.

The 80% rule always puzzled me since as you noted, after taxes, setting up a household, raising kids and saving for retirement, most had no more than 60% (if that) to live on while working. Fortunately, some of the smarter researchers and advisors are pointing out this rather obvious observation.

Although I agree with the premise of the article (no doubt saving early and living frugally should result in a handsome pot of gold to draw on at the end of your journey), I question whether it really matters at what age we retire? Do we really need to forgo a comfortable lifestyle early on (not pure luxury but not extreme frugal guy either) just so we can stop working a 9-5 job earlier in life? Are we really so unhappy with our professions or has retiring early just become another way to “keep up with the Joneses”? I get the extreme saving concept but I also see the merits of those who say, waste now or waste later but in the end you’ll still end up wasting money. Living an extremely frugal lifestyle to me is a kin to someone starving themselves for a period of time only to gorge themselves later down the line. Why not eat a steady diet along the way rather than overly punish or reward yourself at arbitrary intervals in life? I think the proverbial saying, moderation in all things, is just as relevant when it comes to discussions on saving, lifestyle, and retirement. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating an “eat drink and be merry for tomorrow we die lifestyle”, quite the contrary. I prefer a more balanced approach with both personal luxuries and sacrifices sprinkled in throughout. Everyone’s situation is unique but for me once I achieved a relatively comfortable lifestyle my expenses didn’t really increase while my savings and retirement returns have only continued to grow. Just because my expenses don’t increase doesn’t necessarily mean I’m living below my means. If anything I’m living at my means and saving whats left (which should increase with time).

This is the first retirement article out of thousands that addresses lifestyle impact on early retirement. In 1972 I made $85 a week and saved $60 because I lived at home with my parents. I was frugal naturally and have never felt deprived, always able to save 20%-50% of my salary. I attended night school and my day job paid for tuition and joined a big 8 firm at 26 making even more money that I hardly spent. I left my parents at 33 and bought a house that I could pay off in 5 years. I complained that my employer limited my 401k contributions to 15% when I could put in 50% and no sweat. I was laid off at 60 three years ago and retired and claimed social security at 62 which covered my monthly expenses. Since 55 I was laid off 3 times and became convinced nobody would hire an old man. Now with a million dollar in the stock market I am enjoying my retirement and can save even more by not having to pay for stressful commutes, gas, eating out and high sales taxes. I spend 2 hours in the morning reading WSJ and watch CNBC the rest of the day. This is truly the best time of my life and I am happy.

Great article, I have left corporate tax and am transitioning to Financial Planning. Always a saver, worked hard, and limited my consumption. Now I can pursue this career change at 59. I enjoy working and learning. Had enough of corporate tax departments and politics within large corporations. The 3.8% surtax was the motivation I needed to say goodbye to my salary. Hope I can make the world a better place by helping a few people with my life experience and what I have learned and what I am learning.

Never stop accumulating, never stop learning, never give up….

One criticism I would have is that expenses aren’t uniform over a lifetime. They tend to be lumpy around events like sending kids to college and a downpayment for a first home.

But overall the article is spot on in terms of the cost of house you choose, what cars you buy and how often you replace them, and how often you travel and eat out.

Another assumption is that people will live the same lifestyle after and before retirement. Some will drop expenses as they no longer need fancy cars and fancy suits and entertain clients a lot. Others will dramatically increase expenses as they take up travel in retirement. But the overall point is good, as people get locked into fixed expenses like big houses or get used to expensive hobbies or lifestyles, they will find it hard to drop them in retirement. Thus, they will need to work longer to support their perceived needs.