Executive Summary

For all of the myriad ways financial advisors can structure and run their practices, firm owners generally encounter similar stages in the development of their firms. At some point, solo advisors will need to decide whether to increase their headcount, and an ensemble practice may later evolve into a centralized brand with significant enterprise value. The journey will be unique for each advisory firm owner, but one thing they all have in common is that they will eventually have to divest themselves of their ownership stake, either through a voluntary (or involuntary) dissolution of the business or through the full or partial RIA sale, with the latter naturally being the most economically ideal outcome.

In this guest post, Chris Stanley, investment management attorney and Founding Principal of Beach Street Legal, discusses in depth the various stages of buying, selling, and merging an investment advisory and financial planning business.

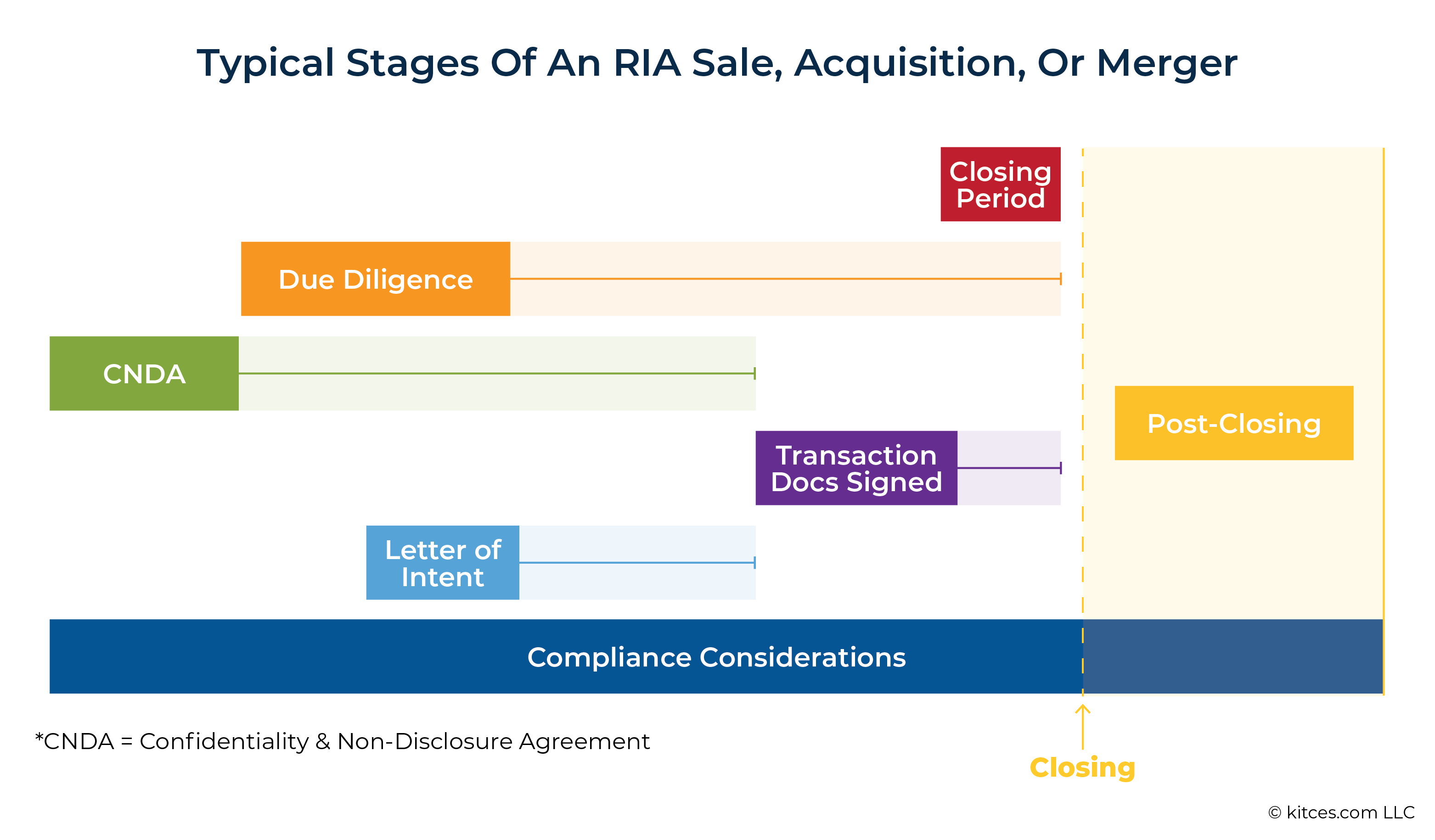

The initial step towards the eventual sale of an advisory firm requires the seller to identify a well-suited counterparty, which can be challenging given the population of well-funded serial acquirers who have a material advantage over firm owners, many of whom have likely never bought or sold a business. Once the seller and potential buyer are ready to get serious about a deal, the next step will be to sign a mutual Confidentiality and Non-Disclosure Agreement (CNDA), which contractually obligates the parties to keep any information that is shared (as the name implies) confidential.

From there, both parties can begin their respective preliminary due diligence. Once they are comfortable with the information and documents that have been shared, they can sign a Letter Of Intent that, while still high-level, provides enough detail about the proposed transaction for the seller to make an informed decision about whether to proceed. At that point, the definitive transaction documents are drafted, providing details around items such as equity and/or asset purchase agreements, a possible promissory note, and a bill of sale. Notably, these documents will serve as evidence in any subsequent disputes, making it imperative for both seller and buyer to fully understand the terms.

Once all that work is completed and both parties are satisfied with the terms of the transaction, it’s time to seal the deal and legally bind themselves by signing the contract. This moves the deal into the closing period, where the transaction can be publicly announced and any closing conditions must be met (such as obtaining consent from the seller’s clients to transition to the new owner). Only then can the new owner begin the work of integrating processes and systems and serving their new clients.

Ultimately, the key point is that the process of transferring ownership of an advisory firm is an immense undertaking and is almost always far more intensive and involved than most parties can imagine. However, given that all advisory firm owners will inevitably face the transfer (or dissolution) of their ownership stake, it’s important to consider what a future sale or merger might look like, as it’s far better for potential sellers to understand the steps involved well in advance rather than trying to figure it out on the fly!

5 Important Legal/Compliance Steps Of Buying, Selling, And Merging A Financial Advisory Firm

A private company and its founder(s) are almost certain to experience at least one of the following 3 occurrences over the course of the company's lifecycle:

- A voluntary wind-down and dissolution of the company's existence by the founder(s);

- An involuntary dissolution of the company's existence by virtue of the death or permanent legal incapacity of the company's founder(s); or

- The full or partial sale of the company to someone other than the original founder(s).

From a purely economic perspective, the 3 nearly inevitable occurrences listed above are listed in order of least to most ideal.

While a voluntary dissolution of the company might sound preferable to an involuntary one, the shuttering of a company without some sort of compensated ownership transfer is the least ideal outcome, even when it's voluntary, because the founder(s) receive exactly $0 in consideration of the business they built.

However, if a company's founder(s) have established a continuity/succession or buy-sell agreement (which is unfortunately still a very big "if" in the investment advisory and financial planning industry) to address the death or permanent legal incapacity of the founder(s), the founder(s) will typically be compensated pursuant to the terms of the continuity/succession or buy-sell agreement – albeit at a comparatively lower valuation that may be heavily contingent on the future retention of clients.

The planned sale or merger of a company while the founder(s) are still alive and with full legal capacity is the most economically ideal outcome, primarily due to the higher comparative valuation that can be ascribed to a company that is not going through the tumult of a founder's death or permanent legal incapacity, and also because of the future earnings potential that the founder(s) may still be able to achieve after the consummation of the planned sale or merger.

Thus, and again purely from an economic perspective, founders of investment advisory and financial planning companies would do well to at least consider what a future sale or merger would entail. As an attorney who advises investment advisory and financial planning company founders on sales, acquisitions, and mergers, I can confidently say that it entails a lot – both from the perspective of the seller and the perspective of the buyer.

What follows is a discussion of the legal and compliance aspects of buying, selling, and merging an investment advisory and financial planning business. This discussion will be by no means exhaustive or representative of all potential transaction structures, but instead primarily contemplates the sale of the entirety of a business to an external third party (and not, for example, a staged internal equity transfer designed to facilitate employee buy-in over time).

The goal is to guide founders along the transaction journey with the various legal documents involved serving as the journey's waypoints.

Step 1: The Confidentiality & Non-Disclosure Agreement (CNDA)

Before actually jumping into Step 1, let's at least acknowledge in passing the critical Step 0 of a transaction's journey: actually finding a well-suited counterparty that is the right mutual fit for a transaction. The buyer's market is still very crowded; well-funded serial acquirers are at an economic and experiential advantage compared to aspiring advisory businesses looking to enter the acquisition game for the first time. From the seller's perspective, it is paradoxically overwhelming to grasp both the universe of potential buyers that exist and the flurry of solicitations that a seller may be receiving, yet at the same time, it may seem impossible to sift through the noise to find the proverbial needle in the haystack that represents the ideal buyer.

It is for this reason that Step 0, at least from what I've anecdotally witnessed, is typically the most protracted 'dating stage' of the transaction journey.

For the sake of this discussion, we'll assume that the buyer and seller have gone out on a few dates, exchanged phone numbers, and are going steady (or, to translate to modern parlance, the buyer and seller have held virtual hands in the Metaverse, exchanged TikTok DMs, and have suspended their respective Tinder accounts). In other words, it's getting serious.

Unlike (most?) evolving romantic relationships, it is at this stage that a buyer and a seller will want to sign a mutual Confidentiality and Non-Disclosure Agreement (CNDA). The purpose of a CNDA is fairly self-explanatory, but it imposes a contractual obligation on both the buyer and the seller to maintain the confidentiality of and not disclose to third parties the information and documents that are to be shared by one party with the other through the next stages of the transaction journey. In addition, the CNDA protects the disclosure of the mere existence of the parties' discussions and the existence of a potential transaction. In other words, the cat can't be let out of the bag until much later in the transaction journey.

To be clear, a CNDA should be signed by the parties before any nonpublic, confidential, proprietary, or trade secret information is shared by one party (the "disclosing party") to the other (the "receiving party"). If any such confidential information has already been shared between the parties, the CNDA that is subsequently signed would ideally be drafted to apply retroactively to such confidential information shared before the execution of the CNDA.

A CNDA should also include certain reasonable exceptions that permit the receiving party to disclose such confidential information as may be required by law (e.g., in response to a court order) and to its third-party professional advisors (e.g., accountants, lenders, and attorneys 😉) who are under the same duty of confidentiality and non-disclosure as the receiving party. It's also unreasonable to attempt to cover information that is publicly available in a CNDA, as such information is – by definition – not confidential.

Once a CNDA is signed, reciprocal preliminary due diligence can commence in earnest. Notwithstanding the existence of a CNDA, a seller should still refrain from disclosing nonpublic personal information about its clients and should instead anonymize or redact such nonpublic personal client information until later in the transaction journey. For example, the household assets under management and recurring revenue attributable to client Jane Doe can be disclosed by the seller for the buyer's due diligence purposes, but the identity of Jane and John Doe should be replaced with 'Client 1' or simply redacted at this early stage of the transaction.

One of the essential documents for the parties to review early in the transaction journey upon the signing of the CNDA is the seller's existing investment advisory and/or financial planning agreements; in particular, the parties should review the agreement's 'assignment' provision to determine how the seller's clients may or must consent to the transfer of their advisory relationship from the seller to the buyer. As will be discussed at length below, client consent logistics can significantly impact the workload, timing, and sequence of transaction events overall.

Step 2: The Letter Of Intent, Term Sheet, Or Memorandum Of Understanding

Once a CNDA is signed, the parties enter into the 'trust but verify' stage of the transaction in which reciprocal due diligence is performed by each party through the exchange of information and documents. Typically, a 'data room' (i.e., a cloud-based document storage environment like Dropbox, Box, Google Drive, etc.) is established to serve as the online repository through which various information and document requests are made and to which responses are uploaded. Ideally, email should not be used to exchange due diligence documents if for no other reason than it becomes an organizational nightmare.

The word "reciprocal" has been intentionally included before "due diligence" to emphasize that while the buyer typically requests an amount of information and documents from the seller that is an order of magnitude greater than a seller typically requests from the buyer, the due diligence process is not a one-way street. Sellers should feel empowered to make reasonable information and document requests from the buyer in order to get comfortable that they are not simply viewing the buyer through rose-colored glasses. The buyer will be, after all, the steward of the seller's clients and their respective life savings going forward.

Assuming the buyer has reached a threshold comfort level with the information and documents provided by the seller thus far (with a recognition that the due diligence process is not yet complete), the buyer will next typically present the seller with what is referred to as a Letter Of Intent (LOI), term sheet, or Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU). Though some practitioners may use different terminology or even separate the LOI, term sheet, and MOU into different components, we'll use the LOI terminology to reflect the agreement in principle that is memorialized by the buyer and presented to the seller.

The presentation of the LOI is where the rubber begins to hit the road, as it will set forth many of the core components of the transaction with at least enough detail for the seller to make a decision to proceed with the buyer or not. For example, an LOI will typically describe the following:

- The high-level legal structure of the transaction (e.g., an asset acquisition, equity acquisition, or merger);

- The financial terms of the transaction (i.e., the purchase price, payment mechanics, and various components and contingencies);

- The transaction agreement(s) to be signed and other material transaction terms (examples of which will be discussed below);

- The seller's liabilities that will or will not be assumed by the buyer (i.e., what the seller will remain liable for and what liabilities will be transferred from the seller to the buyer);

- If structured as an asset acquisition, what assets are specifically excluded from the transaction and not to be acquired by the buyer;

- An exclusivity or "no shop" commitment by the seller (i.e., not to solicit or entertain acquisition offers from other buyers);

- The parties' continuing confidentiality and non-disclosure obligations as memorialized in the Step 1 CNDA; and

- With certain exceptions, the non-binding nature of the LOI (i.e., that the terms of the transaction may change before the parties sign transaction agreement(s) based on what is brought to light in the course of continued due diligence).

The length and detail of an LOI will vary based on the nature and structure of the transaction itself, the aggregate purchase price, and the preferences of the parties and their respective counsel. I've personally seen LOIs that are a single page and others that are up to about 8 pages. On the one hand, the Step 2 LOI stage is not the time or place to iron out each and every minute detail of the transaction (primarily because reciprocal due diligence will continue through the Step 4 signing of the transaction agreements stage and not all stones have even been turned over yet). On the other hand, an LOI that is bereft of sufficient detail will likely bog down the transaction process in Step 3, when transaction agreement(s) are presented – especially if the transaction agreement(s) do not reflect what the seller understood to be the terms of the deal.

I recommend that as many 'big rocks' or 'non-negotiables' be ironed out and addressed in the LOI as possible, which, in turn, will lead to a more streamlined review and negotiation of the transaction agreements and transaction journey overall. In other words, the parties should be forthcoming with each other about what terms – if not included as part of the transaction agreement(s) – will cause a party to walk away.

With full acknowledgment that the following recommendation is inherently biased and may be viewed as self-interested, I implore advisors that are about to embark on a transaction journey to engage qualified legal counsel to be at their side throughout the process. Ideally, counsel should be retained during this Step 2 LOI stage, if not earlier. On transactions in which I've been brought in mid-stream and have had to play catch-up, it often results in more time and expense to get the transaction back on track and clean up (or undo, if at all possible) what may have already transpired that is detrimental to the party I'm representing.

Step 3: The Transaction Agreement(s)

Once the LOI is signed, the parties are off to the races. The pace and detail of due diligence accelerate, meeting frequency between the parties increases, and the buyer's attorney gets busy drafting the definitive transaction agreement(s) for delivery to the seller's attorney.

Depending on the structure of the transaction, one or more of the following agreements may be required:

- Asset Purchase Agreement (for transactions structured as asset acquisitions);

- Equity/Stock/Membership Interest Purchase Agreement, etc. (for transactions structured as equity acquisitions);

- Merger Agreement (for transactions structured as mergers);

- Promissory Note (if the purchase price involves 'seller financing' or the deferral of some component of the purchase price until a later date, with the seller bearing the collection risk as the noteholder);

- Bill of Sale (to effectively evidence the conveyance of assets from the seller to the buyer);

- Assignment and Assumption Agreement (to effectively evidence the conveyance of assumed contractual obligations from the seller to the buyer);

- Joinder to an Operating Agreement, Stockholders Agreement, or Limited Partnership Agreement (if the seller will receive equity in the buyer in partial or full consideration of the sale; this will also vary depending on whether the buyer is organized as, for example, a limited liability company, corporation, or limited partnership);

- Restrictive Covenant Agreement (which typically includes some combination of client and employee non-solicitation covenants and/or non-competition covenants, and which is often included as part of the purchase agreement itself);

- Employment or Independent Contractor Agreement (if the seller or any of the seller's staff will become employees or independent contractors of the buyer as part of the transaction); and

- Promoter/Solicitor Agreement (if the seller or any of the seller's staff will receive additional compensation for future client referrals to the buyer).

While the contents and negotiating opportunities of each of the above-referenced agreements are beyond the scope of this article, suffice it to say that the transaction agreements can be very lengthy, laden with legalese, and are vitally important to understand.

If there is a later dispute between the parties, these transaction agreements will be the evidentiary centerpiece. It is thus vitally important for both the buyer and seller to work in close coordination with their respective counsel to ensure that they accurately reflect your understanding of the terms of the transaction and do not present unnecessary risk or liability.

Again, if most of the 'big rocks' or 'non-negotiables' have been ironed out in the Step 2 LOI stage, then the Step 3 transaction-agreement negotiation stage should theoretically be less controversial. However, I've never been a part of a transaction in which there weren't at least a handful of transaction agreement revisions exchanged between the buyer and the seller to fine-tune the terms, terminology, and allocation of risk between the parties.

Step 4: The Signing

Once the parties are satisfied with their reciprocal due diligence, the transaction agreements have been finalized, and any pre-signing operational or logistical matters have been resolved, the parties are now ready to legally bind themselves to the contractual terms and obligations contained in the transaction agreements by – you guessed it – actually signing them.

In days of yore, this signing process may have occurred in person with a flurry of fountain pens and paper cuts, but nowadays, the signing process is typically performed via electronic exchange of digital signatures on an agreed-upon date using an e-signature software solution.

Once the parties have signed the transaction agreements, a few new workflows are triggered:

- A public announcement can be made, if desired, about the existence of the transaction. For the entire transaction journey until this point, the parties have been subject to the original CNDA that prevented any disclosure of the existence of the potential transaction.

- Clients can be officially notified as to the existence of the transaction and what will be required of them to transfer their relationship from the seller to the buyer. More on this below.

- If applicable, the parties enter the "closing period", which refers to the period of time between the signing of the transaction agreements and the "closing" or consummation of the transaction overall when all "closing conditions" have been satisfied.

A closing period may or may not be applicable depending on the size and structure of the transaction, but if there are any conditions that must be satisfied by a party before the deal can really be done, the closing period is when such conditions must be satisfied.

For transactions involving investment advisers, the most common example of a closing condition is obtaining the consent of the seller's clients to transfer from receiving investment advisory and/or financial planning services from the seller to receiving investment advisory and/or financial planning services from the buyer. In other words, clients generally don't automatically transfer from the seller to the buyer as a matter of law due to the client consent rights built into the Advisers Act and state securities acts or rules; instead, clients are afforded the opportunity to consent to the change of control and/or deemed assignment of their existing investment advisory and/or financial planning agreement with the seller to the buyer.

Client consent can be obtained either via 'positive' or 'affirmative' consent (i.e., a client has to affirmatively act to signify their consent to the change of control and/or assignment by signing a consent form or signing a new investment advisory and/or financial planning agreement with the buyer) or via 'negative' or 'passive' consent (i.e., a client simply has to be provided advance notice of the change of control and/or assignment, but doesn't have to actually respond or do anything to provide their consent).

The viability of affirmative or passive consent is a key determinant of a transaction's overall structure and sequencing, and hinges on whether the parties are state-registered or SEC-registered and what the seller's investment advisory and/or financial planning agreements permit in this regard. It is for this reason that the client consent mechanics should be surfaced early in due diligence. There is less friction in a transaction that only requires passive client consent as opposed to a transaction that requires affirmative client consent, particularly because client consent (or at least a certain threshold of client consent as reflected in the seller's trailing revenue) must often be obtained by the seller in the finite closing period. If viable, sending a blanket change of control or assignment notice to all clients without needing any response is typically preferred to hounding clients to sign and return a form or a new agreement.

On the other hand, if the seller's investment advisory and/or financial planning agreements are woefully out of date, contain language that would expose the buyer to unnecessary risk, or are otherwise just drafted poorly, the parties may want their transitioning clients to sign fresh versions of the buyer's investment advisory and/or financial planning agreements as part of the transaction process – even if a passive consent process was legally permissible. It's also not uncommon for the parties to effect the transfer of client agreements via passive consent just to complete the transaction in a more frictionless fashion, but then work to have transferred clients sign new agreements a few months down the line after the transaction dust has settled.

Other examples of post-signing, pre-closing matters could include the following:

- Written approval of the transaction by the respective parties' members, shareholders, managers, or boards of directors;

- Other consents to the assignment of the seller's agreements with third-party vendors (such as software providers, landlords, equipment providers, sub-advisers, promoter/solicitors, etc.) or, in the alternative, the planned termination of certain third-party vendor relationships that are no longer needed after the transaction's closing;

- Signing of any post-closing employment agreements;

- Various attestations, certificates, or other 're-affirmations' with respect to representations and warranties made in the transaction agreements; and

- Securing post-closing 'tail' or 'extended reporting period' insurance coverage by the seller.

Step 5: Closing & Post-Closing

Assuming all closing conditions have been satisfied, the transaction can be considered officially consummated and done (at least from a legal perspective). Any initial purchase price component is paid from the buyer to the seller, and the assets or equity of the seller are legally transferred from the seller to the buyer. This is the point in time at which the clients of the seller officially become clients of the buyer. It is also the point in time at which any transitioning Investment Adviser Representatives (IARs) of the seller can become IARs of the buyer via the filing of Form U4 by the buyer for all such IARs through the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD).

Though the transaction may be completed from the legal perspective, the transition and integration work is only just beginning. It is at this post-close stage that the integration of processes, systems, technology, personnel, vendor relationships, and workflows can begin in earnest.

In addition, it is only after closing that the seller can withdraw its investment adviser registration (assuming that all clients have transitioned from the seller to the buyer and there is no countervailing reason to maintain the seller's registration as an investment adviser). This is accomplished by filing Form ADV-W through IARD. Similarly, the seller can file Form U5 to withdraw any IAR registrations with the seller.

Compliance Considerations

While the steps of the transaction journey listed above are anchored to the various agreements that will be signed throughout the process, there are important compliance considerations that are unique to transactions involving registered investment advisers that must be accounted for along the way.

Registration Posture

Once the transaction closes, the seller's clients legally transfer to become the buyer's clients. This means that the buyer will have to account for the new post-close aggregate client headcount on a per-state basis for purposes of determining whether it may need to register or notice file in any new states (or whether it would still fall within any applicable de minimis thresholds that afford an exemption from registration or notice filing). A similar post-close registration or notice filing analysis should be performed based on the states in which the seller maintains "places of business" and the states from which the seller's IARs perform advisory services; states still generally require registration (for state-registered firms) or notice filing (for SEC-registered firms) if an adviser has a place of business within their borders – including a home office from which an IAR renders advisory services.

For example, if the buyer is state-registered only in Missouri and is acquiring a firm whose clients are predominantly located in Arkansas, the buyer will need to register in Arkansas before the closing if, upon the closing, the buyer will have exceeded 5 Arkansas-resident clients within the past 12 months.

If the same Missouri state-registered buyer is acquiring a seller that will continue to have a place of business in Arkansas post-closing (and even if no Arkansas-resident clients will become clients of the buyer upon the closing), the buyer will still need to register in Arkansas before the closing due to the newly-acquired Arkansas place of business.

For transactions involving 2 state-registered advisers, the parties should also assess whether the post-closing regulatory assets under management of the buyer will exceed $100 million – in which case the buyer will become eligible to transition from state registration to registration with the SEC.

The overall point is that the parties should assess the registration and notice filing posture of the buyer post-close, and may want to consult this guide for RIAs who may need to switch between state and SEC registration for reference.

Client Consent & Privacy Matters

The considerations and logistics of obtaining the consent of the seller's clients to transition to the buyer have been described at length above, but I'll reemphasize the recommendation that this analysis should be performed early in the transaction journey (ideally during Step 1, once the CNDA has been signed). The downstream effects of an affirmative client consent process and a passive client consent process are very different, and charting this course early will save last-minute scrambling as the parties approach the Step 4 signing stage.

In addition, sellers should remain mindful of their client privacy obligations as required under Regulation S-P and applicable state privacy laws, as well as what their current privacy notice may or may not permit insofar as information sharing in advance of the Step 4 signing stage. Though Regulation S-P may afford certain carve-outs in the context of a transaction, I generally recommend that all advisers' privacy notices expressly permit an adviser to share client information with a third party in connection with an unplanned succession event (like death or permanent legal incapacity) or a planned transaction as discussed herein.

Dual IAR Registration

If any of the seller's IARs will transition to become IARs of the buyer, the parties will need to assess whether the state(s) in which such IARs are registered permit 'dual IAR registration' (i.e., for an IAR to be registered with 2 investment advisory firms at the same time). Some states do, some states do not, and some states only permit dual IAR registration if the two investment advisory firms with whom an IAR is registered are affiliated (i.e., under common control or in a parent/subsidiary relationship). Please refer to the "Dual RA Registration" column of this handy-dandy cheat sheet published by IARD for a state-by-state matrix in this regard.

Dual IAR registration restrictions only really come into play in two scenarios:

- If the buyer attempts to file a Form U4 to register a seller IAR with the buyer, but the seller has not yet filed a Form U5 to withdraw the seller IAR's registration with the seller. In this instance, states that prohibit dual IAR registration may not approve the seller IAR's registration with the buyer until such Form U5 is filed by the seller.

- If there is an intentional overlap or crossover period in which the seller's IARs will remain registered with the seller while also registering as IARs of the buyer. This overlap/crossover period can be necessary if the seller expects to transition clients over to the buyer in tranches or otherwise over an extended period of time that would not otherwise fit into a typical closing period.

There may be creative solutions to maneuver around these dual-IAR-registration obstacles, but attention should be paid to which IARs will temporarily 'stay behind' at the seller and which IARs will make the jump to the buyer.

Post-Closing Record Retention By The Seller

If a buyer acquires all or substantially all of the assets or equity of a seller, most records will transition from the ownership of the seller to the ownership of the buyer. However, Rule 204-2 under the Advisers Act (the SEC's recordkeeping rule) imposes 2 important elements on sellers with respect to their records (and many states impose similar rules).

- Subsection (e)(2) states that "Partnership articles and any amendments thereto, articles of incorporation, charters, minute books, and stock certificate books of the investment adviser and of any predecessor, shall be maintained in the principal office of the investment adviser and preserved until at least three years after termination of the enterprise."

- Subsection (f) states that an investment adviser, "before ceasing to conduct or discontinuing business as an investment adviser shall arrange for and be responsible for the preservation of the books and records required to be maintained and preserved under this section for the remainder of the period specified in this section, and shall notify the Commission in writing, at its principal office, Washington, D.C. 20549, of the exact address where such books and records will be maintained during such period."

A few takeaways:

- The organizational documents that created or maintained the legal existence of the seller as an entity must be retained for at least 3 years post-closing. Though subsection (e)(2) doesn't specifically mention limited liability company articles of organization (which I suspect is because the SEC's recordkeeping rule either predates Wyoming's 1977 adoption of the first limited liability company statute, or at least the period in which limited liability companies really became en vogue), sellers organized as LLCs should still plan to maintain their organizational and entity maintenance records for at least 3 years post-closing.

- The buyer generally assumes responsibility for maintaining the seller's required records post-closing for the time period required by the SEC's recordkeeping rule, but the seller doesn't literally need to pen a letter to the SEC's headquarters in Washington, D.C. to provide the referenced notification. Instead, the seller should add the buyer's name and contact information to Item 8 and corresponding Schedule W1 of the Form ADV-W it ultimately files to withdraw its registration as an investment adviser.

Post-Closing Form ADV, Client Agreement, And Compliance Manual Updates

It likely goes without writing, but I'll write it anyway: The buyer should evaluate whether any post-closing updates to its Form ADV, client agreements, and/or compliance manual will be required. At a minimum, the buyer should at least expect to:

- Prepare (and file, if state-registered) a Form ADV Part 2 brochure supplement for any IARs transitioning from the seller to the buyer;

- Update the employee headcount section in Form ADV Part 1, Item 5.A and Item 5.B;

- If there has been a material change to regulatory assets under management, update Form ADV Part 1, Item 5.D, Item 5.F, and Schedule D, Section 5.K.(3) as well as Form ADV Part 2A, Item 4; and

- Add employees transitioning from the seller to the buyer to the list of supervised persons (and access persons, if applicable).

There may be a variety of other items that may need to be updated to account for inherited promoter/solicitor relationships, custodian relationships, fee schedules, etc., and a thorough scrub of the Form ADV, client agreement, and compliance manual is recommended as the parties approach the closing.

Embarking on the sale or acquisition of an investment adviser is an immense undertaking from the perspective of both the buyer and the seller, and is almost always more intensive and extensive than most parties anticipate. The legal and compliance guideposts discussed herein are only one element of a successful transaction, as the transaction will also need to be viewed through many other economic, tax, operational, logistical, and emotional lenses.

With the start-to-finish legal framework in place, however, hopefully the transaction process can be approached with a more fulsome understanding of what to expect.

Leave a Reply