Executive Summary

While several of today's leading "robo-advisor" companies were founded in the aftermath of the financial crisis, it wasn't until early 2012 that they finally converged on a common low-cost "automated investment service" model... which, coupled with a surge of media coverage, quickly suggested that they could become the future of financial advice (or at least investment management) for consumers.

However, in the year since established players like Schwab and Vanguard launched ‘competing’ services, a fresh look at the robo-advisor landscape reveals that their growth rates are falling rapidly, to just 1/3rd their levels of one year ago. Their apparent demise: an inability to scale their marketing to sustain growth rates in the face of increasing competition and challenging client acquisition costs, coupled with a similar inability to grow their average account sizes.

In fact, the combination of rising client acquisition costs and declining average revenue per client may be an outright death knell for the direct-to-consumer robo-advisor movement, as they approach the unsustainable crossover point where the lifetime value of a client, cumulatively, is less than the cost to acquire a single client (given that some have a mere average gross revenue per client of just $50/year!). Accordingly, it's not surprising to see many of the early robo-advisor players pivoting in other directions, using their long runway of available dollars to try to find greater growth traction, with at best one or two that might manage to build a viable brand that survives.

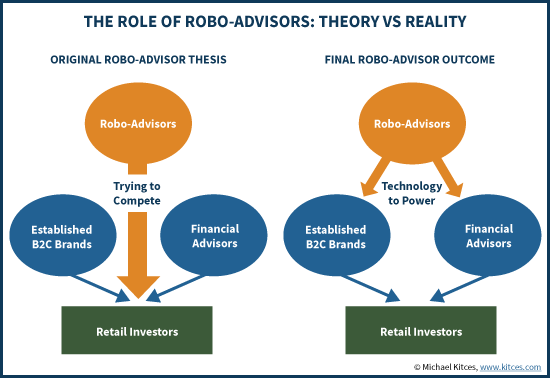

Nonetheless, in the long run we may still look back at this moment as one of significant transition for the industry, not because robo-advisors disrupted human advisors, but because the emergence of robo-advisors was the needed catalyst for the industry to reinvest into the future of financial advisor technology. Already, tech-augmented human advisors are rapidly growing past both their robo-advisor and traditional human advisor peers, and an outright “arms race” of technology is emerging amongst financial advisor custodians and broker-dealers all seeking to be the future platform of choice.

Which means in the end, the direct-to-consumer robo-advisor movement may be dying, with VC funding suggesting Betterment may soon be the last man standing, but the legacy of their technology will continue to be transformative for years to come, just as online brokerage in the late 1990s didn’t disrupt financial advisors but instead became the backbone of how we execute our businesses today!

B2C Robo-Advisors Disruption Started With A Bang

Betterment first launched as the original "robo-advisor" in May of 2010, and later that fall won a Finovate 2010 "Best In Show" award for its simple, self-directed-but-technology-assisted investment solution. In late 2011, a platform aimed at pairing investment managers with investors, previously named KaChing and later Wealthfront, pivoted to become an "online financial advisor" as well, with the vision of disrupting traditional financial advisors by automating the investment management tasks that "expensive" human advisors perform at a price point of only 0.25%. And when a few months later, Betterment lowered its pricing (previously at 0.3% to 0.9%) down to a 0.15% to 0.35% tiered graduated fee schedule as well, the race was on for low-cost "automated investment services" to take over the investment world (with FutureAdvisor pivoting to join the fray a few years later as well).

And early on, the results were promising. After about two years, the platforms were both over $500M of AUM, and their rapid growth fueled a big round of raising $30M+ in capital (each) in early 2014. Using these funds to begin scaling the marketing, it took Wealthfront only another 6 months to cross from $500M+ to the $1B of AUM threshold, and barely another 9 months to cross the $2B threshold by April of 2015. Similarly, once Betterment raised capital, it took about 8 months to move from $500M+ to its first $1B by the end of 2014, and was closing in on $2B just 5 months later.

Yet one year beyond these $2B of AUM thresholds, the environment has shifted significantly. As predicted, 2015 was the year that the established financial services companies launched their competing offerings and tried to undercut existing robo-advisors by throwing in the service “for free”, from Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolios solution with no AUM wrapper fee (because Schwab makes money on most of the underlying fund positions), to Vanguard’s Personal Advisor Services offering a full financial planning solution for a 0.30% cost that’s barely above the price of a robo-advisor’s investment-only service (and includes not just automated investing but a personal financial advisor as well!).

Robo-Advisor Growth Rates Are Plummeting

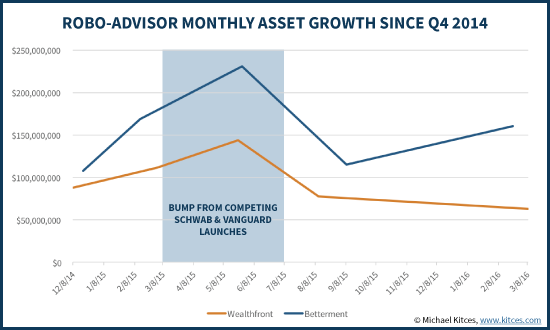

As a result of the rising competition – or perhaps simply the possibility that the total market for purely self-directed automated investment advice is smaller than these companies expected – the pace of new asset flows have remained relatively flat at both Betterment and Wealthfront since the end of 2014. Based on the companies’ latest Form ADV disclosures, the pace of AUM growth at Betterment is around $150M/month, where it was a year ago, and AUM growth at Wealthfront is down to barely $60M/month over the past 6 months.

While the companies did experience an uptick in growth in the second quarter of 2015, in retrospect this appears to have been a function of the increased media buzz of the time. After all, Schwab Intelligent Portfolios launched in March of 2015, and Vanguard’s solution came out of beta last May, which triggered a burst of high-profile media coverage comparing all of the services (with the implicit marketing that entails). Which means once the initial media buzz wore off by the end of the summer, the companies returned to their ‘normalized’ growth rates of around $100M per month (which would be even lower if Betterment's B2B Institutional and 401(k) platforms are excluded).

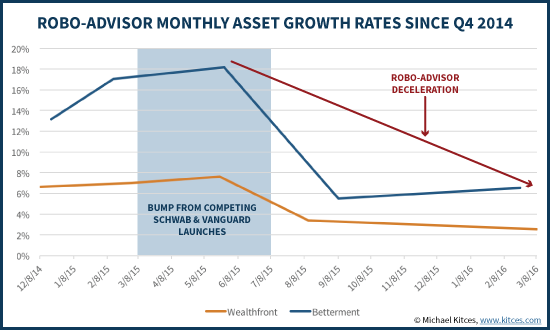

In addition, it’s notable that relative to their growing asset base, drawing in “just” $100M per month actually represents a drastic decline in the growth rates of the companies. After all, in theory growing to twice the AUM and twice the number of clientele should lead to twice the asset growth for the company thanks to twice as many clients who can refer, allowing it to maintain a consistent growth rate.

Instead, relatively flat net flows supporting an ever-growing asset denominator is causing robo-advisor growth rates to crash, with both Wealthfront and Betterment growth rates falling to just 1/3rd of their levels from a year ago.

Given that Morningstar estimated last year that robo-advisors need at least $16B and as much as $40B of AUM just to cover core operating costs and recoup advertising expenses, and that robo-advisors may need $50B - $80B of AUM or more to justify their $500M - $700M company valuations, the current linear growth pace of even $150M per month implies that Betterment and Wealthfront may not even reach $10B of AUM by 2020, a mere 1/200th the size of what a sensationalist A.T. Kearney study projected for robo-advisors just a year ago!

Are Client Acquisition Costs Burying B2C Robo-Advisors?

To say the least, falling growth rates for robo-advisors suggests that client acquisition – and in particular, scaling client acquisition – is becoming a significant (if not fatal) challenge for today’s robo-advisors.

The first sign of this shift was when robo-advisors began to pivot to “traditional” advertising approaches to promote their digital business, from television commercials for both Betterment and also Wealthfront, to Betterment’s much-buzzed-about ads on the roofs of NYC taxicabs. If the vision of these companies was to be a digital solution for digital natives, why the explosion of ‘analog’ marketing strategies?

Second, the robo-advisors have been increasingly shifting from their original core B2C market in search of new growth channels. For Betterment, this has included everything from complementing their Millennial-centric service with a “RetireGuide” for boomers, to the launch of Betterment Institutional for advisors, to their Betterment for Business 401(k) offering. In the case of Wealthfront, it’s been not only building on their Direct Indexing 2.0 solution, but an increasingly aggressive approach of giving their services away for “free” to get users, from Wealthfront.org providing non-profits a waiver of management fees on the first $1M of AUM, to Wealthfront in the Workplace for employers to cover employee management costs for the first $100,000, to simply offering to manage the first $10,000 of client accounts for free. Last July, Wealthfront dropped its minimums all the way down to $500 just to encourage new users to at least try them out (and undercut Schwab Intelligent Portfolios’ $5,000 minimum), and more recently just announced its Wealthfront 3.0 platform with a bevy of 'non-traditional' integration partners (including Venmo, LendingClub, and Coinbase) and an announcement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) features, even as commentators have noted that it's not clear how any of this will help Wealthfront's growth in the foreseeable future.

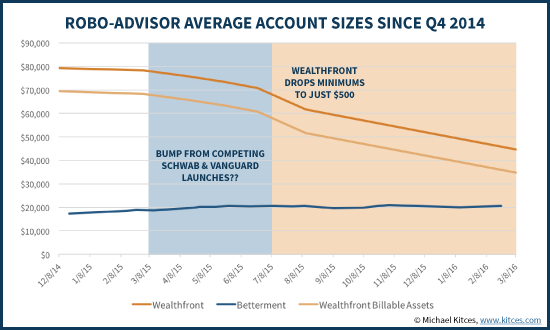

Of course, I’ve actually been an advocate of some of these programs, from Betterment’s pivot into serving financial advisors (and a 401(k) space that clearly needs some structural improvements!), to the tremendous potential of Wealthfront’s Indexing 2.0 solution. Nonetheless, the rise of competition from traditional financial services firms like Schwab and Vanguard appear to be increasingly boxing Betterment and Wealthfront into their original channel of Millennials with “small” investment accounts. Accordingly, despite launching more and more of these new initiatives, Betterment’s average account size has remained pegged around $20,000 since Q4 of 2014, and Wealthfront’s average account assets have plummeted over 40% and are converging to Betterment levels as well. Especially when recognizing that Wealthfront waives fees on the first $10,000, so their billable average account size is even closer to Betterment.

This is very troubling from the perspective of purported robo-advisor “disruption”, as the whole principle of Clay Christensen’s “Disruptive Innovation” relies on the business growing and moving upstream over time – with a rising Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) to support it – while Betterment’s APRU appears flat and Wealthfront’s is crashing (likely driven in large part by its recent decision to drop its minimums to $500 and aggressively market to such accounts). In other words, robo-advisors said they were going to disrupt financial advisors, but instead they’re being boxed into the small accounts that financial advisors weren’t serving anyway.

In addition, falling average account sizes may simply be a death knell for the B2C robo-advisor business model altogether. An average account size of $20,000 produces revenue of just $50 per year at a 0.25% fee schedule. Even if robo-advisors are managing to achieve a 98% monthly retention rate and facing just 2% monthly churn, their annual retention rate will be barely 80%, which equates to projected lifetime client revenue of just $250 cumulatively. This is rather troubling, given at least one UK study recently estimating robo-advisor acquisition costs of $312 per client, and Morningstar estimating client acquisition costs could be as high as $1,000 per client for some. In other words, robo-advisors may be spending more to get clients than they are ever expecting to receive, cumulatively, in revenue from those clients.

And that’s simply based on gross revenue, before considering the operating costs of the business. Even if we “generously” assume at the margin that robo-advisors can achieve 50% profit margins on a per-client basis, that’s a cumulative lifetime client value of $100 at an 80% retention rate (and before considering discount rates and cost of capital!). If robo-advisors are spending $300 per client to generate $100 of profit per client, it’s just a matter of time before they burn through their venture cash, especially given the charts above showing that margins are not expanding and revenue-per-client is actually falling!

And these are the stats from amongst the purported “leaders” in robo-advice. Amongst the other players, the outlook is even bleaker. After all, Google announced that it would be shutting down its Google Compare (previously Google Advisor) service altogether in March, Hedgeable reports only $43M on its latest ADV, and two years after WiseBanyan’s Herbert Moore published a controversial article predicting that “You Will Be Investing For Free In 5 Years” using robo-advisors, the service has only a paltry $49M of AUM (and of course, zero revenue, since it’s free, though the company launched its "WiseHarvesting" tax loss harvesting service for 0.25% six months ago, which simpy puts it in direct pricing and services competition with other robo-advisors instead). Nor does it look much better overseas, as leading UK robo-advisor Nutmeg has lost both its CEO and COO in the past month, too.

In addition, it's notable that the growth rates of robo-advisors are slowing even in a bull market. None have yet faced the impact of a bear market, which is likely to hit robo-advisors even harder than traditional advisors, both because their younger clientele tend to be invested more aggressively (so their portfolios will be more volatile to the downside), and their younger clientele are more likely to be laid off and be forced to stop their contributions (as the young and inexperienced are, sadly, usually the first to be fired in a recession), and when their younger unemployed clients need to tap their savings to make ends meet they'll likely liquidate their robo-advisor accounts first (which don't have the tax penalties that would be associated with liquidating their 401(k) plans instead).

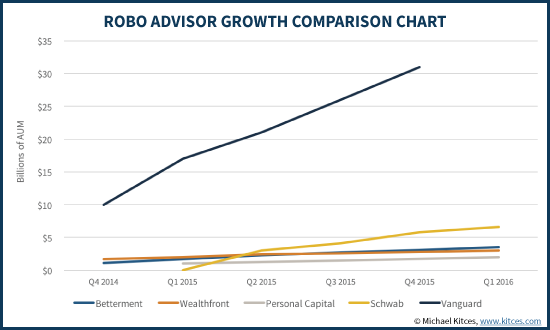

In the meantime, established financial services firms are using their established brands to quickly outpace the original B2C robo-advisors, either by packaging the robo-advisor offering as another managed account on its platform (Schwab), or offering a full-on human-tech hybrid financial planning offering (Vanguard). Because these companies can leverage their existing B2C brands to achieve a drastically lower client acquisition cost, and as a result the sheer volume and scale of their growth makes the other robo-advisors look like their growth is already flat!

B2C Robo-Advisors May Be Dying, But Their Technology Won't

Ultimately, it appears that robo-advisors are failing (to validate their VC valuations, and possibly their business models altogether) because they misunderstood the fundamental problem that the financial services industry faces in serving small accounts and young investors. The issue is not the operational efficiencies in serving them – which technology is particularly effective at solving.

In other words, like bringing a knife to a gun fight, the robo-advisors brought an operational cost efficiency solution to what is fundamentally a marketing and client acquisition cost problem.

Nonetheless, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the robo-advisor technology solutions are “bad” at serving clients effectively and providing value to them. Given the funding they've already raised, today's existing crop of robo-advisors will likely continue fighting to grow, and serving their clients, for years to come. And in fact, I suspect the collective industry angst over the rise of the robo-advisors derived quite directly from the embarrassing light the robo-advisors shined upon the too-often-mediocre technology solutions we use as ‘traditional’ advisors and larger financial services institutions. None of us appreciated how bad our technology was, because we were all comparing to everyone else’s similarly-bad tools. The robo-advisors provided a new point of comparison, and it was very embarrassing for everyone.

In turn, the mismatch of robo-advisors to the marketplace (solving an operational efficiency challenge but unprepared for the client acquisition challenge), coupled with the industry’s desire to improve its own technology capabilities, has driven the mass robo-advisor pivot over the past year, from being a B2C solution to a B2B (or B2B2C) solution instead. From Jemstep’s pivot from B2C to B2B (and subsequent acquisition by Invesco), to FutureAdvisor’s switch from B2B to B2B when Blackrock purchased it, to Northwestern Mutual buying LearnVest and John Hancock buying Guide Financial, Envestnet buying Upside Advisor and Yodlee, and Fidelity buying eMoney, the traditional industry is hungry to step up on the technology front. And of course, that’s before we consider the companies that decided to build their own solutions rather than acquire, including Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolios (and Intelligent Institutional Portfolios for advisors), and Vanguard’s Personal Advisor Services.

And notably, even as robo-advisors were hailed in the media as the future of investing, the funding to existing robo-advisors has drastically slowed (with Betterment the only player to raise significant capital in the past year, though several have enough dollars in the bank to keep fighting for years to come), and the pace of new robo-advisor company launches has ground to a virtual halt. The slowdown of capital to robo-advisors seems to be driven by the realization (finally) of VC funds that a robo-advisor without an innovative solution to the client acquistion cost challenge will be dead on arrival. Accordingly, while it may still take many years for the early robo-advisors to work through their existing venture capital dollars, it's not surprising that the few and only robo-advisor platforms now emerging are those that already have an existing membership or readership to reach, where the robo-advisor solution is simply a way to monetize the current audience, not an "if you build it, [hope] they will come" offering. As long as they don't raise "too much" capital and exceed the realistic size of their markets, the upcoming "robo-advisor" solutions like the one for Krawcheck's Ellevate network and Steinberg's WorthFM (marketed to 1,000,000+ DailyWorth readers) should have good potential to go into the (automated) investment management business with their existing audiences.

Technology Isn’t Replacing Advisors, It’s Augmenting Them

What these dynamics reveal is that robo-advisors aren’t replacing financial advisors; the technology is being used to augment financial advisors, as shown by the explosion in FinTech buy-and-build activity by established financial services companies... the ultimate outcome that was predicted from day one on this site 4 years ago. Whether you want to call them “cyborg” advisors (as I once did), or prefer Joe Duran’s “bionic” advisor label, these tech-augmented hybrid human advisors who are leveraging technology are growing fast. Just witness the explosive growth of Vanguard’s solution (which is not a robo-advisor but a tech-augmented human solution, and is now over $30B, or nearly 10X the size of the nearest robo competitor). Or the fact that Personal Capital (another not-actually-robo-but-tech-augmented human platform) is as large as Wealthfront and Betterment combined when measured on the basis of revenue instead of assets.

Still, it’s equally important to recognize that these tech-augmented solutions aren’t just beating the robo-advisors. They’re growing faster than most human advisors, too, as one industry benchmarking study after another is showing that technology-centric human advisor firms are outpacing their fellow advisor peers on everything from revenue growth to profits.

In other words, what was originally framed as a battle of “robots versus humans” was misguided from the start. At best, robo-advisors were not serving the people that traditional human advisors were serving anyway. At worst, robo-advisors set out to disrupt with a model that is now proving to be neither disruptive (as average revenue per client isn’t growing) nor even viable (as client acquisition costs appear to exceed lifetime client value, especially given the lack of any revenue-per-client growth). Thus, again, we see that no serious new B2C robo contenders have emerged at all in the past two years (without already being attached to an existing mega-B2C brand), the only ones even considering the space now have both a very targeted client acquisition channel from which they can grow (e.g., WorthFM or Ellevest), and venture capital dollars have shifted from funding an array of new companies to staking $100M on Betterment to being the one lone survivor of the original class of B2C robos under the fundraising acceleration thesis (which doesn't bode well for the ability of competitors like Wealthfront to attract and retain talent).

Nonetheless, the emergence of the robo-advisor has accentuated what is quickly becoming an arms race of technology for traditional financial services firms, as advisors demand better technology than doing account applications with fax machines (still true for many platforms!!) and using the industry's available rebalancing software solutions (many of which were designed more than 10 years ago). In turn, advisor platforms are quickly seeking to build or acquire it to provide it to them, and the tech-augmented humans are increasingly pulling ahead of both their robo and human counterparts. Though notably, the long-term winners will still be the ones that also figure out how to solve the client acquisition cost challenges of getting clients – which, again, is a marketing problem, not a “robo” problem – as just putting robo-advisor technology on a website and waiting for clients to show up is not likely to work for human advisors any better than it did for robo-advisors! In other words, most advisors, broker-dealers, and custodians, who just slap a robo-advisor self-service portal onto their websites will be even more dismayed by the results than the B2C robo-advisors have been (as at least those firms had some Millennial marketing strategy to drive results!).

Ultimately, what this all means is that, even as the B2C robo-advisor movement is dying, and the VC funders suggest Betterment may soon be the last man standing, the legacy of their technology impact is only beginning. Just as online brokerage in the late 1990s didn’t disrupt financial advisors and instead became an offering of B2C brands (e.g., Schwab.com) and eventually the core platform that advisors use to operate their businesses (every cloud-based custodian and broker-dealer platform today), so too is robo-advisor technology is shifting from a B2C solution, to one part of a product line for a B2C company, and eventually will simply be the next evolution of technology upon which the entire industry operates. In fact, I suspect that today’s environment may mark as significant a technology transition for financial advisors over the next 15 years as the explosion of the internet and online brokerage was in boosting the success of financial advisors for the past 15 years!

So what do you think? Are we witnessing the slow death of the robo-advisor, or is their best growth still yet to come? Do you think "robo technology" is relevant to traditional financial advisors? How will we look back on this "robo era" 10 years from now?