Executive Summary

Roth conversions are, in essence, a way to pay income taxes on pre-tax retirement funds in exchange for future tax-free growth and withdrawals. The decision of whether or not to convert pre-tax assets to Roth is, on its surface, a simple one: If the assets in question would be taxed at a lower rate by converting them to Roth and paying tax on them today, versus waiting to pay the tax in the future when they are eventually withdrawn, then the Roth conversion makes sense. Conversely, if the opposite is true and the converted funds would be taxed at a lower rate upon withdrawal in the future, then it makes more sense not to convert.

But what exactly is the tax rate that should be used to perform this analysis? It’s common to look at an individual’s current level of taxable income, determine which Federal and/or state income tax bracket they fall under based on that income, and assume that would be the rate at which the individual will be taxed on any funds they convert to Roth (or the amount of tax savings they would realize in the future by reducing the amount of their pre-tax withdrawals).

However, for many individuals, the tax bracket alone doesn’t accurately reflect the real impact of the Roth conversion. Because of the structure of the tax code, there are often ‘add-on’ effects created by adding or subtracting income – and these effects aren’t accounted for when simply looking at one’s tax bracket.

For example, when an individual is receiving Social Security benefits, adding income in the form of a Roth conversion could increase the amount of Social Security benefits that are taxed so that the increase in taxable income caused by the Roth conversion is more than ‘just’ the amount of funds converted – in effect, the increase in income can magnify the tax impact of the conversion beyond what the tax bracket alone would imply. However, the same effects are also true on the ‘other’ end of the Roth conversion, where any reduction in tax caused by replacing pre-tax withdrawals with tax-free Roth withdrawals could also be magnified by an accompanying decrease in the taxability of Social Security benefits.

The upshot is that the conventional wisdom of deciding whether (or how much) to convert to Roth based on tax brackets alone won’t always lead to a well-informed decision. Instead, finding the ‘true’ marginal rate of the conversion (i.e., the increase or decrease in tax that is solely attributable to the conversion itself) is the only way to fully account for its impact. Additionally, understanding the true marginal rate can make it possible to time conversions in order to minimize the negative add-on effects (e.g., avoiding Roth conversions when doing so will also increase the taxation of Social Security benefits) and maximize the positive effects (e.g., using funds converted to Roth to reduce pre-tax withdrawals when doing so will decrease the taxation of Social Security) – thus maximizing the overall value of the decision to convert assets to Roth.

Roth conversions are a tax-planning strategy that many individuals use to reduce the impact of taxes on their retirement portfolios. When someone holds funds in a tax-deferred retirement account like a traditional IRA or pre-tax 401(k) plan, they are allowed to ‘convert’ some (or all) of those funds by rolling them into a Roth IRA. Although the amount of the conversion is taxable at ordinary income rates in the year of the conversion, the newly converted Roth funds can grow tax-free thereafter, with future withdrawals of both principal and earnings being fully excluded from income tax.

The usefulness of Roth conversions stems from the fact that they can be used to take advantage of shifting tax rates over time. In essence, they allow taxpayers to choose when to pay taxes on their retirement account funds – and when properly timed, they can ensure that those funds are taxed at the lowest rates possible.

For example, a taxpayer in an uncharacteristically low-income year – such as someone who has retired but has yet to file for Social Security benefits – can convert funds to a Roth account and pay taxes on the conversion at lower rates than they would if they were to withdraw the funds later when their income was expected to be higher. This effectively locks in a permanently low tax rate on the funds that are converted to Roth, since they will never be taxed again (so long as they are withdrawn according to the rules for qualified Roth distributions). For this reason, Roth conversions are especially popular for recent retirees, particularly in the ‘gap years’ before Social Security kicks in.

Roth conversions have had particular relevance lately on account of what has been happening in the broader economic and financial environment. Bear markets, such as the one so far in 2022, create a unique opportunity for converting pre-tax funds to Roth, because lower overall portfolio values often mean that individuals can convert a greater proportion of their funds than when the value is higher. Additionally, many individuals have taken earlier-than-planned retirements in the COVID era, giving them additional low-income years where Roth conversions at low tax rates would be possible.

But despite being more favorable overall as of late, Roth conversions don’t necessarily make sense for everybody. The trade-off between paying taxes today (on funds being converted to a Roth) versus paying later (when leaving funds in a tax-deferred account) means that Roth conversions only make economic sense if the funds converted to Roth would be taxed at a lower rate today than they would be by leaving them alone until a later date.

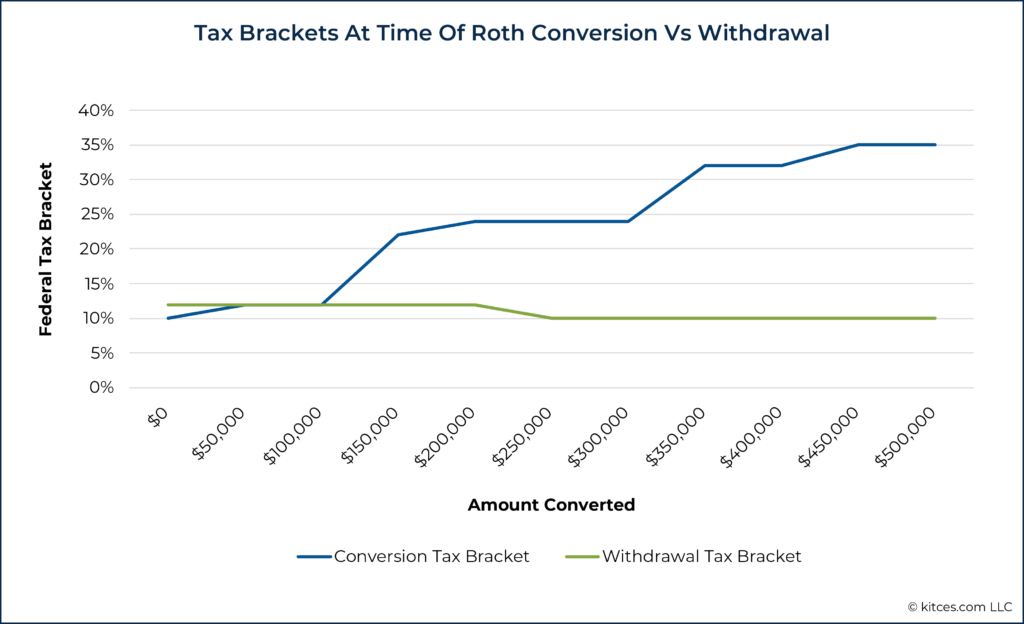

Additionally, even when it is a good idea to do a Roth conversion, it isn’t always clear how much of an individual’s pre-tax funds should be converted to Roth. That’s because Roth conversions themselves can push an individual’s tax rates higher by increasing their taxable income in the year of the conversion, reducing the advantage of paying the tax sooner – and a large enough conversion can negate or even reverse the tax benefits by being taxed at a higher rate than would be paid in the future. In general, the higher the amount of the conversion, the more taxable income it adds in a given year.

The key point is that both decisions – when it’s a good idea to convert funds to Roth, and how much to convert when doing so – require a comparison between the potential cost of increased taxes today versus the expected benefits of reduced taxes in the future.

Current Vs Future Tax Rates And The Tax Equivalency Principle

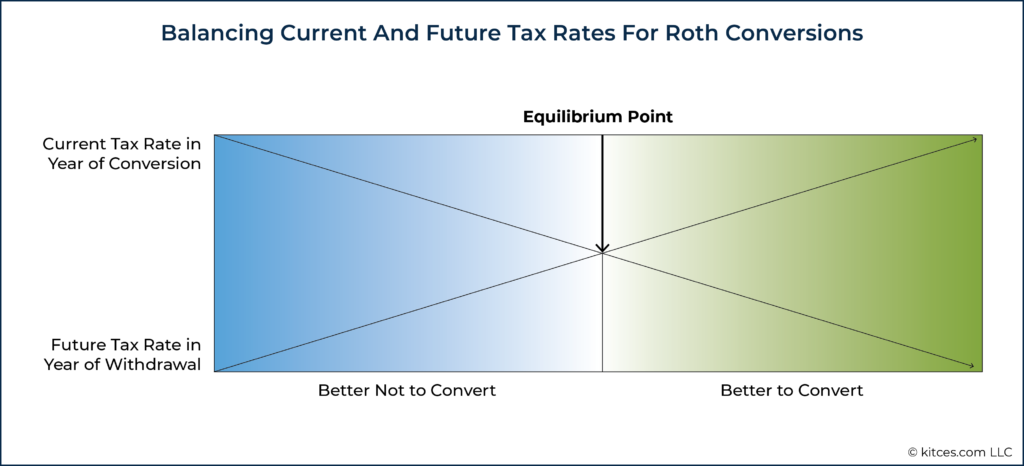

Typically, the way to make the comparison between current and future taxes when doing a Roth conversion is to compare the taxpayer’s current and future tax rates; specifically, the rate at which the funds would be taxed if they were converted to Roth today versus the expected rate at which the distributed funds would be taxed in the future if they weren’t converted to Roth and instead remained tax deferred.

When converting pre-tax funds to Roth would result in a lower tax rate on those dollars today, instead of a higher tax rate on a distribution of tax-deferred funds made in the future, it makes economic sense to do the Roth conversion now, since doing so effectively locks in a permanently lower tax rate on the converted dollars. Conversely, if the tax rate paid in the year of the Roth conversion is higher than the expected future tax rate, it’s generally better to wait to pay the tax until withdrawing the funds (or until the individual’s tax situation is more advantageous for a Roth conversion). And if the tax rates are the same at both points in time, there is equilibrium – the two outcomes will be economically equal and Roth converting funds would generally have no economic impact on the taxpayer’s situation.

In other words, the decision of whether or not to convert funds to Roth can be boiled down to three simple rules:

- If the converted funds will be taxed at a lower rate today, convert them to Roth.

- If the funds can be taxed at a lower rate upon withdrawal in the future, don’t convert them.

- If the funds would be taxed at the same rate at both points…well, it doesn’t matter whether they are converted or not (because both options would have the same wealth outcome in the end).

When deciding how much to convert, the key concept to understand is that Roth conversions have diminishing benefits as the amount of funds converted to Roth in any given year increases.

In the year of the conversion, if the increased income is enough to bump the taxpayer into a higher tax bracket, it reduces the benefit of converting those funds to Roth. Conversely, if the conversion reduces the individual’s future income (by replacing pre-tax withdrawals with tax-free Roth withdrawals) enough to bump the taxpayer into a lower tax bracket, the benefits of having converted the funds are reduced even further. And if the conversion is large enough, at some point it will effectively cross over the equilibrium point, such that converting any additional funds would cause them to be taxed at a higher rate than they would have been in the future.

In short, the more funds that are converted to Roth in a given year, the less potential benefit there is in converting additional funds in the same year (to the point where converting more funds would create negative value). Which means that it’s a best practice to limit the amount of the conversion to avoid diminishing or even reversing the tax benefits – and like the decision of whether or not to convert funds to Roth in the first place, this decision is based on an analysis of how those additional funds would be taxed today versus in the future.

Tax Brackets Don’t Account For The Add-On Effects Of Roth Conversions

While the above rules outlining when to make a Roth conversion may seem like the decision is a simple process, the reality is a little more complex. That’s because determining which point in time has the lower tax rate requires actually calculating the individual’s current and estimated future tax rate – and how those tax rates are calculated matters when it comes to accurately determining which strategy will result in the lower tax.

The simplest and most common approach is to compare the individual’s current and future tax brackets – i.e., the amount of Federal and/or state tax that will be owed on their next dollar of taxable income. A common rule of thumb is that individuals in the lower (10% and 12%) Federal tax brackets should generally convert (or contribute) funds to Roth, while those in the higher (32%, 35%, and 37%) brackets should generally avoid or defer income. Those in the middle (22% and 24%) brackets might find themselves going either way, but in any case, the determination is made based primarily – or solely – on the individual’s income tax bracket.

Tax Bracket = Tax Owed On Next $1 Of Taxable Income

While this approach may be the simplest, it relies on a key assumption: that the rate implied by an individual’s tax bracket is actually the same rate at which the Roth conversion will be taxed. For example, it assumes that for an individual in the 12% tax bracket who converts $10,000 of traditional funds to Roth, the tax owed on that conversion will be 12% × $10,000 = $1,200. Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case – meaning that relying on the tax bracket alone might not fully capture the effects of the Roth conversion, and therefore might lead to a poorly informed decision on whether (or how much) to convert to Roth.

Recall that tax brackets are used to determine the amount of tax that will be owed on the next dollar of taxable income. For example, if a taxpayer is in the 32% tax bracket, adding $1 of taxable income will add $0.32 to their tax bill.

The caveat, however, is in the phrase “taxable income”. Thanks to the complexity of the US Tax Code and its labyrinth of phaseouts, deductions, and credits, a given change in gross income (i.e., income before any adjustments, deductions, or credits) will not necessarily result in an equivalent change in taxable income. In effect, then, the ‘real’ tax rate on a given change of income – such as when doing a Roth conversion – won’t always equal the rate implied by the individual’s tax bracket.

One area where this effect frequently comes into play is the taxation of Social Security income: Depending on the taxpayer’s existing income, anywhere from 0% to 85% of Social Security benefits may be included in their taxable income, with increased income resulting in taxation of a higher percentage of benefits (i.e., the dreaded ‘tax torpedo’ of rapidly increasing taxable income as taxable non-Social Security income causes more Social Security income to become taxable in turn).

Consequently, for individuals in or around the range where adding or subtracting income might also affect the taxation of Social Security income, adding income from a Roth conversion might not only add taxable income by virtue of the conversion itself, but also cause a higher percentage of Social Security to become taxable. In this case, the actual tax rate paid on the conversion might far exceed the individual’s nominal tax bracket!

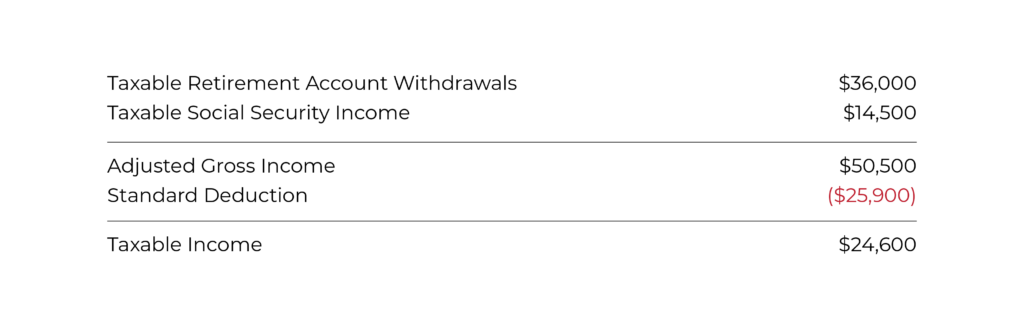

Example 1: The Gladdens are both 70 years old and married, with $36,000 of combined annual Social Security benefits. They take an additional $36,000 of taxable withdrawals from their traditional IRA. They are currently in the 12% income tax bracket.

Using an online calculator to determine their taxable Social Security benefits, their taxable income for 2022 breaks down as follows:

Knowing that they will need to take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from their tax-deferred account starting at age 72, which could bump them up to a higher tax rate in the future, the Gladdens want to convert some of their traditional IRA funds to Roth this year to take advantage of their current lower 12% bracket.

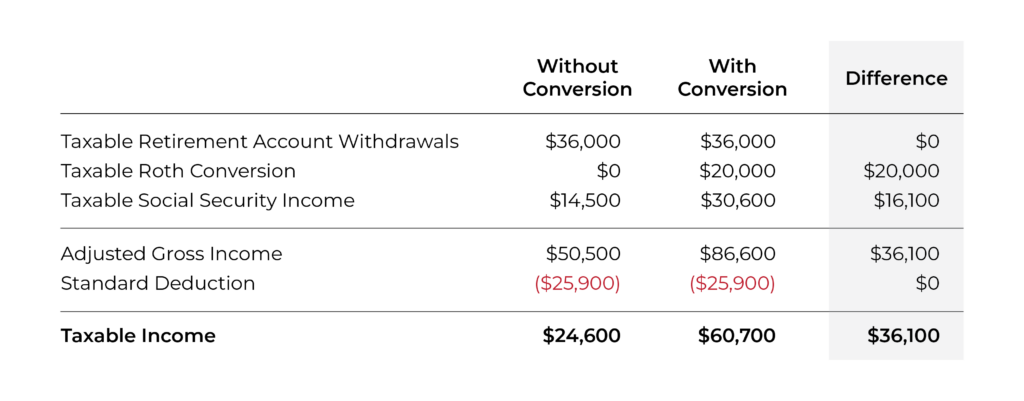

If they decide to convert $20,000 of traditional IRA funds to Roth, here’s how their income would break down now compared to their income without the Roth conversion:

The Roth conversion added $20,000 to their total income; however, the additional income also increased the taxable amount of their Social Security income by $16,100 – which means that the $20,000 increase in total income resulted in a $36,100 increase in taxable income.

At a 12% Federal tax rate, the additional tax on the conversion would be 12% × $36,100 = $4,332. Which means that the ‘real’ marginal tax rate on the converted funds was $4,332 (change in tax) ÷ $20,000 (change in income) = 21.66%.

In other words, the ‘equilibrium’ rate – i.e., the rate that the Gladdens’ future tax rate would need to exceed in order to make the conversion worthwhile – is not 12% as their tax bracket implies, but instead nearly 22%!

The above example illustrates how the tax impact of adding income from a Roth conversion can be magnified in an undesirable way by causing a higher percentage of an individual’s Social Security income to become taxable. On the other hand, though, the so-called tax torpedo can have the opposite effect on the other end of the Roth conversion, when withdrawals from pre-tax traditional accounts are replaced by tax-free Roth withdrawals. In this case, the effects of reducing future taxable income are magnified as the decreased income lowers the taxable amount of Social Security income – and thus benefits those who are able to reduce their pre-tax withdrawals by converting pre-tax funds to Roth.

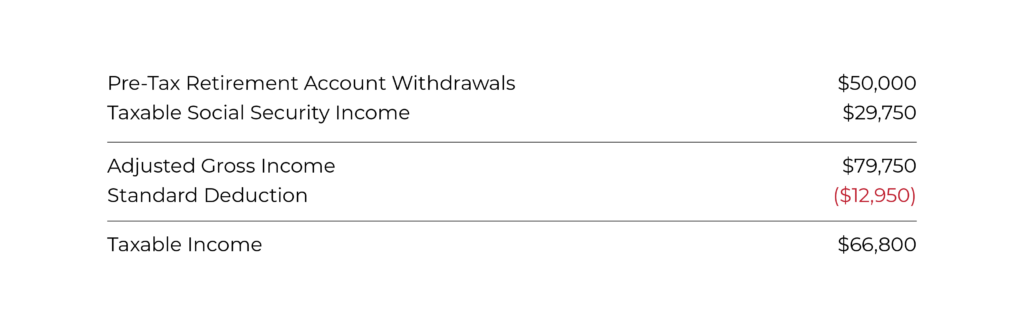

Example 2: Viola is a 70-year-old single retiree whose income consists of $35,000 in annual Social Security benefits and $50,000 in taxable retirement withdrawals.

Her taxable income breaks down as follows:

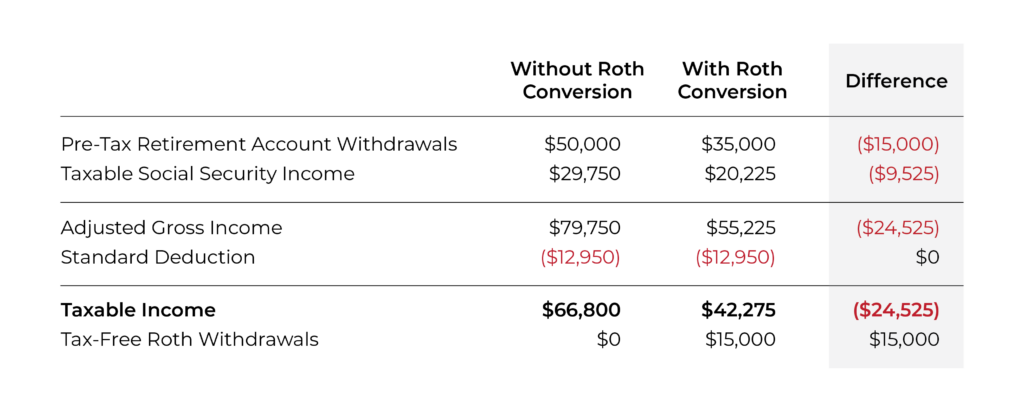

Viola’s current income puts her in the 22% tax bracket. However, if she were able to replace some of her pre-tax retirement withdrawals with tax-free Roth withdrawals, it would have a much greater impact on her taxes than the bracket implies. Here is Viola’s original taxable income picture (with only pre-tax withdrawals) compared with what it would be if $15,000 of her pre-tax withdrawals were replaced with tax-free Roth withdrawals:

The effect of reducing Viola’s pre-tax retirement account withdrawals by $15,000 is that the taxable amount of her Social Security income is also reduced by $9,525, resulting in a total reduction in taxable income of $24,525. At a 22% Federal tax rate, this results in 22% × $24,525 = $5,395.50 in tax savings, which equates to a $5,395.50 ÷ $15,000 = 35.97% marginal tax reduction on account of reducing pre-tax withdrawals – despite the fact that she stayed within the 22% tax bracket all along.

In other words, the equilibrium rate on this conversion – in this case, the rate which the tax on the funds that are converted to Roth must be lower than in order to make the conversion worthwhile – is 35.97%, and not 22% as Viola’s tax bracket alone would imply.

Tax brackets, used by themselves, also might prove ineffective for analyzing Roth conversions when the size of the conversion itself causes the taxpayer to move into a different bracket. While tax brackets calculate the amount of tax on the next dollar of income, Roth conversions can involve differences of tens of thousands of dollars or more – enough to span across multiple tax brackets.

When this happens, a single tax bracket won’t sufficiently capture the full effect of the Roth conversion: For example, if a taxpayer in the 24% tax bracket were to add enough taxable income via a Roth conversion to bump them up into the 32% tax bracket, the actual rate at which the conversion will be taxed (all else being equal) would not be 32%; instead, it would be somewhere between 24% and 32%, since the additional income spans both brackets.

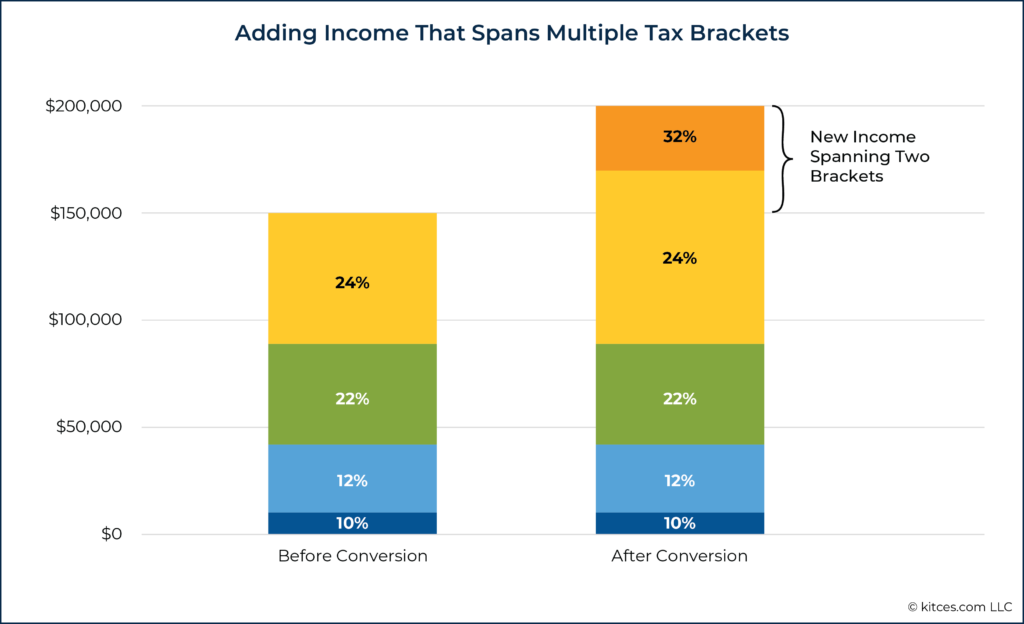

Example 3: Kent is a single taxpayer with $150,000 of taxable income. This places him within the 24% Federal tax bracket, which ranges from $89,075 to $170,050 of taxable income in 2022.

If Kent converted $50,000 of pre-tax funds to Roth (assuming no add-on effects of the additional income, like taxation of Social Security), the new income would span both the 24% and 32% brackets, as shown below:

In this case, even though Kent starts out in the 24% tax bracket, only the income up to the next 24% threshold of $170,050 will be taxed at 24%; the remainder will be taxed at 32%.

Which means that the tax on the new income would be (24% × ($170,050 – $150,000)) + (32% × ($200,000 – $170,050)) = $14,396, which results in a blended tax rate on the Roth conversion of $14,396 ÷ $50,000 = 28.8%.

As illustrated in the examples above, tax brackets have limited usefulness in analyzing the impact of a Roth conversion. The only time an individual’s tax bracket would actually equal the full effect of the conversion would be if the resulting change in income didn’t span multiple tax brackets, and there were no add-on effects of the change in income as well.

True Marginal Tax Rates Are A More Accurate Way To Calculate The Value Of A Roth Conversion

When modeling any scenario that involves either adding or subtracting income from a baseline amount – which is essentially the case with a Roth conversion – what ultimately matters when comparing the two values isn’t the individual’s tax bracket; rather, it is the total change in tax that matters most. In other words, it’s necessary to find out how much of the taxpayer’s tax liability would decrease or increase solely as a result of doing the Roth conversion.

The amount of positive or negative change in tax for each dollar of income that is added or subtracted is the marginal tax rate for the change. In the case of a Roth conversion, where taxable income is added (in the year of the conversion) and subtracted (when making tax-free withdrawals later on), there are two marginal rates to calculate: the rate in the year of the conversion, and the rate in the year(s) of withdrawal.

Calculating the marginal tax rate on the income generated in the year of the Roth conversion involves subtracting the total tax liability without the Roth conversion from the tax liability with the Roth conversion (i.e., the net change in tax liability), then dividing that amount by the total amount converted from traditional to Roth.

Marginal Tax Rate Of Roth Conversion In Year Of Conversion = Change In Tax Liability ÷ Amount Of Conversion

This is the only way to truly gauge the full impact of the Roth conversion because it represents the change in taxes that is solely attributable to the conversion itself.

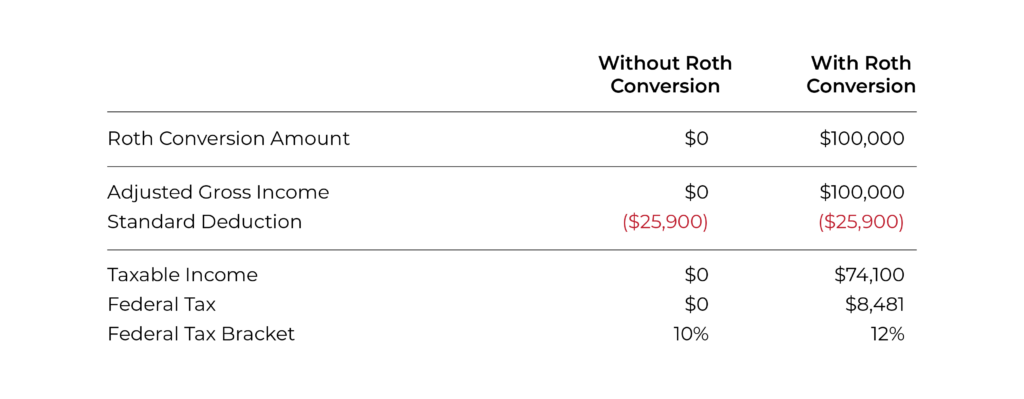

Example 4: The Pucketts are a couple who retired at the beginning of this year at age 60. They have enough savings in cash to avoid making any withdrawals from their retirement portfolios this year, and their advisor is analyzing their options for converting $100,000 of their pre-tax retirement assets to Roth.

The Pucketts’ advisor creates the following pro-forma tax projection for the year the conversion takes place:

Since the marginal tax rate equals the change in tax divided by the amount of the conversion, the marginal tax rate for this conversion would be ($8,481 – $0) ÷ ($100,000) = 8.5%.

Because Roth conversions affect an individual’s taxes both at the time of the conversion (by adding income to the amount of the funds converted) and at the time the funds are eventually withdrawn (by reducing income by the amount of the funds that were converted to Roth), accurately analyzing a Roth conversion requires calculating the marginal tax rate for both periods.

Notably, calculating the future marginal tax rate requires making two key assumptions: what other income (such as Social Security and taxable investment income) the taxpayer will have available, and how much of the taxpayer’s pre-tax retirement withdrawals can be replaced by tax-free Roth withdrawals after the conversion.

After that, the calculation of the marginal rate is the same as above – except that instead of dividing the change in tax by the amount of the conversion itself, the change in tax is divided by the amount of pre-tax withdrawals that are replaced by Roth withdrawals. Since this should reduce the amount of taxable income (and therefore tax paid), this calculation will be measuring the marginal rate of tax decrease in the year(s) of withdrawal.

Marginal Tax Rate Of Roth Conversion In Year(s) Of Withdrawal = Change In Tax Liability ÷ Amount Of Pre-Tax Withdrawals Replaced By Roth

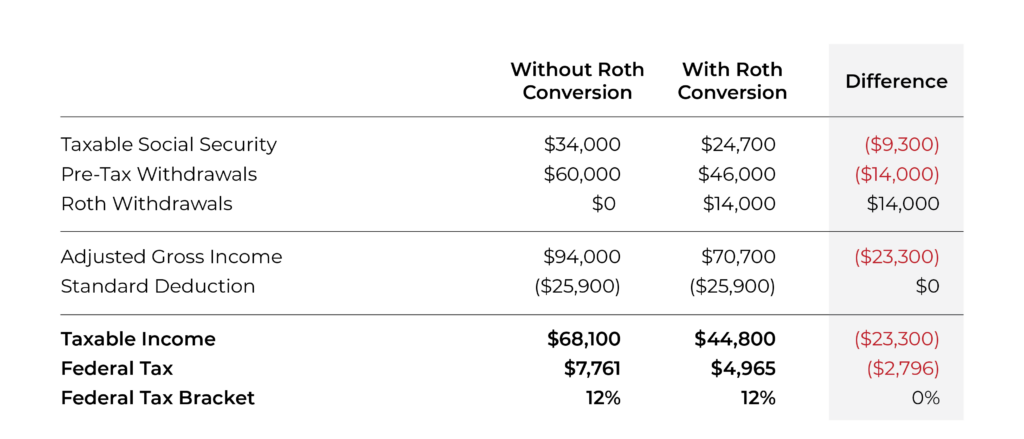

Example 5: The Pucketts from Example 4 above are planning to claim Social Security at age 70 and estimate their combined pre-tax benefits to be $40,000 per year. They were also planning to withdraw an additional $60,000 per year from their pre-tax retirement funds, adding up to a total of $100,000 of (pre-tax) income. At their income level, 85% of their Social Security benefits (equaling $34,000) would be subject to income tax.

Their advisor estimates that by converting $100,000 of their pre-tax funds to Roth today, they would be able to replace about $14,000 per year of their future pre-tax withdrawals with tax-free Roth withdrawals from ages 70–90, with the remaining $60,000 – $14,000 = $46,000 per year coming from their tax-deferred portfolio.

The Pucketts’ advisor creates another pro-forma tax projection for the withdrawal years (stated in today’s dollars):

By replacing their pre-tax retirement withdrawals of $14,000 with tax-free Roth distributions instead, the couple has also reduced the taxable amount of their Social Security income by $9,300, amounting to a $23,300 net reduction in taxable income.

With the difference in tax equaling $2,796 and the amount of pre-tax withdrawals replaced by Roth withdrawals equaling $14,000, the marginal rate of the tax decrease on the conversion is $2,796 ÷ $14,000 = 20.0%.

Comparing this number with the 8.5% marginal rate of the tax increase for the conversion in the previous example, the Pucketts would realize 20% – 8.5% = 11.5% in tax savings by doing the Roth conversion.

Why is this important? Because without going through the analysis using marginal tax rates, and instead simply looking at an individual’s tax brackets, an advisor might come to a different (and less-informed) conclusion about whether – or how much – to convert to Roth.

For instance, in Examples 4 and 5 above, converting $100,000 to Roth would have bumped the Pucketts up into the 12% tax bracket in the year of the conversion, while in the year of withdrawal they would have been in the 12% bracket with or without the conversion.

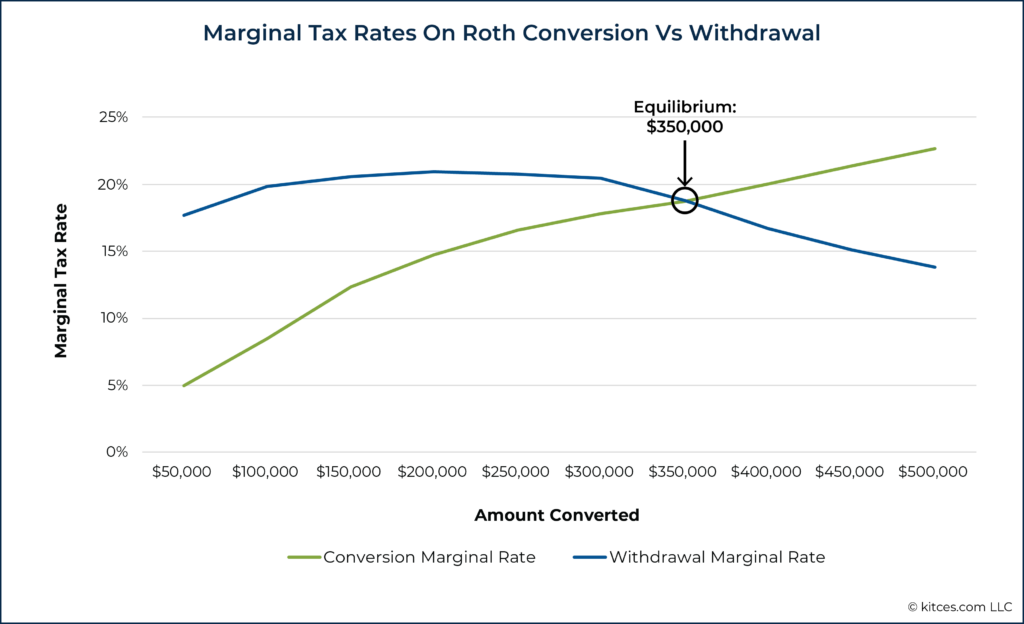

Conventional wisdom says that at this stage, they had reached the ‘equilibrium point’ where their 12% current tax bracket equaled their 12% future tax bracket. And as shown below, converting much more than $100,000 would have bumped them up further into the 22% bracket, which an analysis based on tax brackets alone would have predicted to result in higher taxes overall, since the future tax bracket at the time of withdrawal would now be lower than the tax bracket at the time of conversion:

However, because of the add-on effects of adding or subtracting income that aren’t accounted for when looking at tax brackets alone – in this case, the way that taxation of Social Security decreases when pre-tax withdrawals are replaced by Roth withdrawals – the equilibrium point turns out to be much higher. In fact, the Pucketts could convert significantly more than $100,000 – up to about $350,000 in total – and still come out ahead based on the ‘true’ marginal tax rate of the conversion.

Best Practices For Roth Conversion Analysis

Like most tax-planning decisions, analyzing the effects of a Roth conversion is not a one-size-fits-all process. Even if an individual’s goals and retirement income picture could be whittled down into a single tax bracket, that piece of information alone would still not be enough to decide whether (or if so, how much) to convert pre-tax retirement funds to Roth.

A more well-rounded analysis, then, requires considering additional factors beyond just the individual’s tax bracket. As shown above, the add-on effects of adding and subtracting income may be most pronounced in the case of Social Security taxation, but they can show up in other cases as well, such as:

- When increased ordinary income drives capital gains income into higher tax brackets;

- When increased Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) results in a higher threshold for medical expenses that can be deducted on Schedule A (which is currently fixed at 7.5% of AGI);

- When increased taxable income results in a reduction in the Section 199A deduction on Qualified Business Income for owners of ‘specified service businesses’; and

- When increased income causes certain state tax benefits (such as income-based exclusions of Social Security or pension income) to become phased out.

The effects can even show up in areas that aren’t generally included in the marginal tax rate calculation: For example, the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA) for Medicare premiums is based on the individual’s income from two tax years ago, meaning that, for taxpayers on Medicare (or who are within two years of enrolling), doing a Roth conversion could have a tradeoff in the form of (temporarily) higher premiums.

The key point is that an awareness of all these factors is critical for maximizing the value of a Roth conversion. That’s because this information can be used to time the Roth conversion in order to minimize the add-on effects of the additional income in the year of the conversion, and to maximize the add-on effects of the reduced income when the funds are eventually withdrawn. Doing so can not only push the equilibrium point of the conversion higher (and thus allow for higher amounts to be converted to Roth), but it can also ensure that the individual realizes the highest overall tax savings from the funds they do convert.

For example, converting funds to Roth before the individual has filed for Social Security benefits avoids the add-on effects of increased Social Security taxation (because there is no Social Security income to be taxed to begin with). On the flip side, waiting until after Social Security benefits have begun to start replacing pre-tax withdrawals with tax-free Roth withdrawals can potentially maximize the add-on effects of reducing Social Security taxation. Combining these two strategies (if their age and income requirements make it possible) would give the individual even more bang for their buck on the Roth conversion.

One other consideration is that in order to create a better analysis than a back-of-the-envelope calculation based on simple tax brackets, it’s necessary to have a method to accurately calculate the current year’s tax impact of the Roth conversion and to reasonably project the impact in future years. Although some old-school planners may use spreadsheets to create these analyses, tax planning and financial planning software can make the process quicker and simpler.

For example, tax-planning software such as Holistiplan can be used to create different current-year scenarios to calculate the additional tax that would be owed on various conversion amounts. And for projecting the impact on future years, financial planning software like RightCapital has the capability to model the complex effects of changing income from Roth conversions, including increased or decreased taxation of Social Security.

When comparing any two tax strategies, the ultimate goal is usually to find the option that will result in paying the least amount of tax overall (and retaining the most wealth as a result). In a situation like a Roth conversion, the question is whether the funds in the account will be taxed at a lower rate by paying tax today (by converting dollars from traditional to Roth) or by doing so later (by keeping them in the traditional account and paying tax on withdrawal).

But the way in which tax rates are calculated to make a comparison matters greatly. Simply using the taxpayer’s current and future tax brackets is ineffective because they don’t actually capture the full effect of the conversion itself. It is essential to factor in the add-on effects of more income (in the year of conversion) and less income (at the time of withdrawal) to fully account for the impact of the Roth conversion.

By understanding how to calculate the ‘true’ marginal tax rates of Roth conversions (both in the year of the conversion and the year[s] that funds are eventually withdrawn) by recognizing the add-on effects (like taxation of Social Security income) that Roth conversions can create and by leveraging these effects to maximize the positive impact and minimize the negative, advisors can help their clients find the strategy that creates the greatest tax savings in the long run.

Great to see IRMAA considered in this article. It’s frequently overlooked, and constitutes a real (albeit first world) problem. Slipping into the next tax bracket as a result of Roth conversion may be a little painful, but it’s a “marginal” pain since a taxpayer is paying increased tax on the incremental income only.

With IRMAA, it may be one small step for the tax payer, but one giant leap for the federal government. For example, under current IRMAA brackets, if an individual has modified adjusted gross income up to $123,000, then IRMAA is $65.90/month. However, if that individual has just $1.00 more on the modified adjusted gross income line — or $123,001, then IRMAA is $164.80. That’s almost a $1,200 per year IRMAA increase for an extra $1.00 in annual income. Yikes!

My sense is that if a planner is going to go to these lengths to analyze this for a client, then she should also consider the “cost” of taking money out of a Roth IRA (that forfeited tax free growth has a value after all) before the pre-tax accounts are exhausted. It seems to me that the benefit to the client of this analysis is very speculative, especially since the lost value of the tax free growth would be pretty hard to quantify.

Good point, Kay, and you’re right that there are definitely going to be opportunity costs that are hard to quantify, even if you know about them in advance. But one thing I’d add is that you don’t actually NEED to withdraw from the Roth to recognize the marginal benefits of the conversion. If converting pre-tax assets to Roth results in reducing the size of RMDs that the client doesn’t need for cash flow purposes but is required to withdraw anyway, then that’s a benefit of the conversion even if the Roth assets are never touched.

Why are you using the incorrect standard deductions in the examples? They are all for people/couples over 65 yet do not account for the additional deduction they are entitled to…

Tax equivalency of the different ira accounts is true only for one year. For subsequent years the traditional ira suffers tax drag due to taxes on dividends and capital gains as detailed by McQuarrie here:https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3860359

Ralph,

The tax equivalency of different IRA accounts holds over longer time horizons as well, to the extent that any taxes paid on the conversion come FROM the IRAs in the first place (i.e., it’s a closed system).

If there’s an assumption that we’re looking not ONLY at the IRAs, but also at outside bank or brokerage accounts (with outside cash or outside taxable investments to pay the tax liability), then tax drag on those outside accounts becomes a factor.

We detailed this in our original writing about the economics of Roth conversions back in 2009 – see https://www.kitces.com/to-roth-or-not-to-roth-may-2009-issue-of-the-kitces-report/ – very similar to McQuarrie’s work once you add in outside accounts to the picture.

– Michael

Thank you and your team so much for articles like this. Often it takes me a while to fully understand and I suspect that is the case also with this.

Thanks for the link to the 2009 article which says ” a traditional IRA with a taxable side account will not grow as effectively as a Roth IRA over time”. For me this says that simply looking at tax equivalancy would be sub-optimum. Because of the reduced tax trag for the Roth IRA, doing a conversion at a modestly higher tax rate than one would pay in the future will still result in higher wealth given enough time.

“..the traditional ira suffers tax drag due to taxes on dividends and capital gains”

That is a common explanation for ‘what is going on’ that does not stand up to any math analysis. The withdrawal tax is an allocation of principal between the account’s two funders/owners (you and the gov’t). Neither of your profits nor theirs is ever taxed.

You can play with the numbers using the opening tab of my spreadsheet at https://www.retailinvestor.org/ods/USspreadsheets.xlsx

Really great article. Thank you so much for this work!

the other big piece here is RMDs. the fact that Roth’s don’t have them for someone, and that can carry over to a spouse, and also no taxes on for 10 years while growing money for a non spouse beneficiary, makes the roth exponentially more valuable.

add that tax changes under Secure and Secure 2.0 seem to make leaving money to your beneficiaries in a ROTH the best option for them, if you have the luxury of putting the consideration of your beneficiaries’ future tax burden above your own present and future tax burden (meaning they aren’t forced in RMDs from a pre-tax account that might push them into a higher bracket)

Suffering from confusion, please help me understand because I think this article will be very helpful but I’m struggling with how to do my own example.

The Roth Conversion happens in a particular year, it’s straight forward to determine the marginal tax rate on different amounts converted.

But withdrawals occur for many years (hopefully!) and RMD amounts get bigger. Someyears no withdrawals from the Roth account will be needed. How does one calculate the marginal tax rate on the withdrawal there is no Roth Withdrawal? What year does one pick to calculate the marginal tax rate on the Roth Withdrawal?

Good question. The way I laid it out in the examples above was that pre-tax withdrawals are replaced with tax-free Roth withdrawals over a certain period of time, and that everything was relatively steady over those years so that the marginal tax rate on the withdrawal for one year was representative of that for all years.

But the reality is you don’t actually NEED to withdraw from the Roth to realize the marginal tax effects of the conversion – you only need to somehow reduce the amount of pre-tax withdrawals that occur over time. For example, if converting a chunk of pre-tax funds to Roth reduces the amount of RMDs that need to be taken over the retiree’s lifetime, that reduction (or more specifically the subsequent reduction in tax) is the marginal effect of the withdrawal.

The basic way to account for this is to do like I did and assume each year will be relatively steady and the tax effects won’t change much from the first year to the last. The more accurate (but more time-intensive) way would be to look at each individual year, calculate the marginal rate for that year, and come up with a weighted average of the whole. Financial planning software can certainly aid with this in coming up with cash flow and tax projections for different scenarios – but the problem with trying to get TOO detailed is that the projections are almost certain to be wrong to some degree, which makes the time spent on them less valuable.

To me, it’s about striking a balance between the big-picture considerations and the small-picture details. For example, you can get a reasonable picture of whether someone will be in the income zone that affects the taxation of Social Security by running a future cash flow projection. This could tell you that a Roth conversion might add significant value (by reducing pre-tax withdrawals) without having to specifically calculate the marginal rate for each year. If you want to get very specific on how much to convert, you can go deeper, but at some point adding layers of detail has diminishing returns. But just that one step – considering factors that will be affected by the conversion beyond just the tax bracket – is tremendously valuable, since it brings the analysis into the reality of how taxes are actually calculated and paid.

Ben, Thank you for helping me get my minds around this. Again great article!

A large enough Roth Conversion may trigger IRMAA taxes two years down the road. This would not show up in the marginal tax rate calculation for the conversion, yet it is part of the cost to convert. How can one account for these lagged charges with this method of analysis?

Even more significant for early retirees is the ACA premium tax credit which decreases as income increases. For those above 400% of the federal poverty level ACA premiums are 8.5% of MAGI so the true marginal tax rate is the federal and state rates plus 8.5%.

Michael,

I like your thorough treatment of the subject, but let me ask you, would you really spend your Roth money to avoid 22% in marginal tax if your overall effective tax rate was only 7%. I sure wouldn’t. I stay below the top of the 12% bracket and plan for the fact that my SS income whatever it is will be taxed at 10.2% (15% is free) and I use any headroom in the 12% bracket to lower my TIRA balance, which is more valuable long term because it keeps me in a lower tax bracket. Stop and think for a minute why in the “totality” of retirement it is hard to make spending Roth money work for you if you are getting that Roth money from a conversion. A conversion adds “extra” tax that is not necessary otherwise and all things being equal will leave retirement income at a lower level – the same way eliminating savings once you retire makes the retirement income need lower.

One other comment you made a couple times also leads the novice to the wrong impression and that is that Roth money grows tax-free, implying that your portion of TIRA money does not grow tax free, which I’m sure you know it does. Fixed tax rate in/out of 25%. Person 1 takes $10k and buys 100 shares of ABC stock in their TIRA sets 25 shares aside for IRS while the other 75 shares grow tax free for her to do whatever she wants. Person 2 takes $10k earnings, sends $2500 to IRS and buys 75 shares of ABC stock in a Roth that also grows tax free for him. Both have the same total to spend in retirement after taxes.

Also remember what the person who does the Roth conversion gives up besides his money is the choice to make a better or more informed decision later.

My current concern which has not been addressed by any Roth conversion calculators is:

Is it more cost effective to keep the Traditional IRA intact for life and pay the higher tax on the inherited IRA because the sum allocated toward taxes can also grow inside the IRA for many years. This especially applies to retirees over age 73 currently forced to take RMD and already in a high tax bracket but that bracket will go even higher if the Inherited IRA must be paid out in 10 years due to current SECURE Act rules. Has anyone attempted to research this or develop a calculator that includes this?

I’ve read your article and most of the questions/responses you received but am still a little uncertain if doing a Roth conversion is in my best interest. My wife and I are 74 YO and our financial planner has suggested that we take $58K from our IRAs and do a Roth conversion. This will still keep me in the same tax bracket, 22%, if I don’t do a conversion. I realize that doing this conversion will reduce my overall SS income due to increases to Medicare Part B and D for both me and my wife while on the positive-side will slightly reduce our RMD. Our SS income is presently taxed at the maximum 85% rate and with the annual RMDs that we anticipate we will have to take, our SS income will most likely always be taxed at an 85% rate. We have agreed that we don’t need to leave our children any money when we both have passed. If I project that our taxable income (RMDs + 85% SS + some annual capital gains and dividends) should remain in the 22% tax bracket – unless our mandated RMDs dramatically increase (not a bad thing!), how does doing a Roth conversion make sense? I’ve also read that one should only use their Roth account as a last resort; only after all other taxable retirement money has been spent. Based upon all of the above information, how would a Roth conversion work on our behalf? Thanks.

Absolutely fabulous article, specially for a novice trying to understand the complexity of ROTH Conversions.

Several points never mentioned in all of the many conversations read/listened to on the internet and with CFA/CPA’s, on ROTH Conversions.

Awesome Article, Thanks for sharing this insight!